Abstracts

Drug interaction is a clinical event in which the effects of a drug are altered by the presence of another drug, phytochemical drug, food, beverage, or any environmental chemical agent. The incidence of adverse reactions caused by drug interactions is unknown. This lack of information is compounded by not knowing the number of patients who are prescribed combinations of drugs that can potentially interact. Patients who will or will not experience an adverse drug interaction cannot be clearly identified. Those with multiple diseases, with kidney or liver dysfunction, and those on many drugs are likely to be the most susceptible. Patients with autoimmune diseases are at higher risk for drug interactions. In addition to representing a risk for the patient and jeopardizing the health care provided by professionals, drug interactions can increase dramatically health care costs. This review article approached the clinically relevant interactions between the most used drugs in rheumatology (except for non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and corticosteroids) aiming at helping rheumatologists to pharmacologically interfere in the disease processes, in the search for better outcomes for patients and lower costs with the complex therapy of chronic diseases they deal with.

drug interactions; drug therapy; antirheumatic agents; rheumatic diseases

Interação medicamentosa é um evento clínico em que os efeitos de um fármaco são alterados pela presença de outro fármaco, fitoterápico, alimento, bebida ou algum agente químico ambiental. A incidência de reações adversas causadas por interações medicamentosas é desconhecida. Contribui para esse desconhecimento o fato de não se saber o número de pacientes aos quais foram e são prescritas as combinações de medicamentos com potencial para interações. Não é possível distinguir claramente quem irá ou não experimentar uma interação medicamentosa adversa. Possivelmente, pacientes com múltiplas doenças, com disfunção renal ou hepática e aqueles que fazem uso de muitos medicamentos são os mais suscetíveis. Dentre as condições que colocam os pacientes em alto risco para interações medicamentosas está o grupo de portadores de doenças autoimunes. Além de apresentarem um risco para o paciente e um insucesso para o profissional da saúde, as interações medicamentosas podem aumentar muito os custos da saúde. O objetivo desta revisão é abordar as interações clinicamente importantes das drogas mais usadas em reumatologia (exceto os anti-inflamatórios não esteroide e corticosteroides) com o intuito de auxiliar os prescritores reumatologistas no desafio de intervir farmacologicamente nos processos de doença, buscando melhores desfechos para os pacientes e menores gastos com a complexa terapêutica das doenças crônicas sob sua responsabilidade.

interações de medicamentos; terapêutica; antirreumáticos; doenças reumáticas

REVIEW ARTICLE

IAdjunct Professor of Pharmacology of the UFG; Master's degree in Physiology at the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais; PhD in Health Sciences at the UFG

IIProfessor of Rheumatology; Service of Rheumatology; Department of Internal Medicine - HC-FM-UFG; PhD in Rheumatology at the Universidade de São Paulo

Correspondence to

ABSTRACT

Drug interaction is a clinical event in which the effects of a drug are altered by the presence of another drug, phytochemical drug, food, beverage, or any environmental chemical agent. The incidence of adverse reactions caused by drug interactions is unknown. This lack of information is compounded by not knowing the number of patients who are prescribed combinations of drugs that can potentially interact. Patients who will or will not experience an adverse drug interaction cannot be clearly identified. Those with multiple diseases, with kidney or liver dysfunction, and those on many drugs are likely to be the most susceptible. Patients with autoimmune diseases are at higher risk for drug interactions. In addition to representing a risk for the patient and jeopardizing the health care provided by professionals, drug interactions can increase dramatically health care costs. This review article approached the clinically relevant interactions between the most used drugs in rheumatology (except for non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and corticosteroids) aiming at helping rheumatologists to pharmacologically interfere in the disease processes, in the search for better outcomes for patients and lower costs with the complex therapy of chronic diseases they deal with.

Keywords: drug interactions, drug therapy, antirheumatic agents, rheumatic diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Drug interaction is a clinical event in which the effects of a drug are altered by the presence of another drug, phytochemical drug, food, beverage, or any environmental chemical agent. When two drugs are administered concomitantly to a patient, they can act independently or interact with each other, increasing or reducing the therapeutic or toxic effect of one and/or the other. Sometimes, the drug interaction can reduce the efficacy of a drug, and be as harmful as the increase in its toxicity. Some interactions can be beneficial and useful, justifying the concomitant deliberate prescription of two drugs.1

The incidence of adverse reactions caused by drug interaction is unknown and varies from study to study, depending on its design, population assessed (elderly, children), and the outpatient or hospitalized patient condition, the latter usually using a greater number of drugs. This lack of information is compounded by not knowing the number of patients who are prescribed combinations of drugs that can potentially interact.

A pharmacological and epidemiological study2 of drug interactions carried out in a Brazilian university-affiliated hospital has assessed 1,785 prescriptions of adult wards and has found the following: each patient received, on average, seven drugs (ranging from two to 26); 49.7% of the prescriptions comprised drug interactions, 23.6% being considered moderate and 5%, severe; 17.9% of the prescriptions had more than one drug interaction. The study has assessed 33 medical records containing prescriptions with severe drug interactions and evidenced the presence of adverse reactions due to drug interaction in 51.5% of the patients. The authors compared their results with those of other three studies also performed in Brazil, which assessed prescriptions for psychiatric patients (22% of the prescriptions with drug interactions), pediatric patients (33% of the prescriptions with drug interactions), and hospitalized patients (38% of the prescriptions with drug interactions).2

Patients who will or will not experience an adverse drug interaction cannot be clearly identified. Those with multiple diseases, with kidney or liver dysfunction, and those on many drugs are likely to be the most susceptible. The elderly population often fits that description; therefore, many cases reported involve elderly individuals on several drugs.1

The magnitude of the problem of drug interactions increases significantly in certain populations in parallel with the increase in the number of drugs used. The interactions that can be of lesser clinical significance in patients with less severe forms of a disease can significantly worsen the clinical condition of patients with more severe forms of the disease. According to Brown,3 the following conditions put patients at high risk for drug interactions:

1. High risk associated with the severity of the disease being treated: aplastic anemia, asthma, cardiac arrhythmia, diabetes, epilepsy, liver disease, hypothyroidism, or intensive care.

2. High risk associated with the potential for drug interaction of the therapy: autoimmune diseases, cardiovascular diseases, gastrointestinal diseases, infections, psychiatric disorders, respiratory disorders, and convulsions.

Patients with rheumatic diseases usually have a higher number of comorbidities and usually undergo complex therapeutic regimens. The hypothesis that the use of a large number of drugs relates to the advanced age of those patients, long disease duration, disease activity, functional deficit, and large number of comorbidities seems reasonable. Treharne et al.,4 assessing 348 patients undergoing treatment for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), have reported that the total number of drugs prescribed to each patient was, on average, 5.39, reaching a maximum of 16 drugs for the same patient. Of the drugs prescribed, only 2.4 were for the specific treatment of the disease. Longer duration of the disease and more advanced age of the patients were predictors of a higher total number of drugs, which was explained by the elevated number of comorbidities in the most elderly patients with longer disease duration. The authors recommend the regular review of the treatment plan of RA patients by health professionals specialized in rheumatology to assess the risk/benefit ratio of each drug and their interactions.

In addition to representing a risk for the patient and jeopardizing the health care provided by professionals, drug interactions can increase dramatically health care costs, because of both the increase in the number of hospitalization days and the higher need for laboratory tests to monitor the outcomes of hospitalizations.5

The search for review articles in English, French, and Spanish in the PubMed database (1998-2008) with the keywords drug interactions and DMARDs (disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs) in human beings revealed 568 references. We chose to look for review articles, because the search without that filter resulted in 3,224 articles comprising isolated studies for each drug or studies related to their prescription by dermatologists, nephrologists, or oncologists. Other studies reported the use of immunosuppressants in transplanted patients, who, by receiving different doses of some immunosuppressants intended to treat rheumatic diseases, are exposed to different conditions of potential interactions.

This review article approached the clinically relevant interactions between the most used drugs in rheumatology (except for non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and corticosteroids) aiming at helping rheumatologists to pharmacologically interfere in the disease processes, in the search for better outcomes for patients and lower costs with the complex therapy of chronic diseases they deal with. This article approaches the potential drug interactions of the following drugs: azathioprine, chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab. The drug interactions reported in this study are cited in the following sources:

National Therapeutic Form (Formulário Terapêutico Nacional) - 20086

Micromedex® Drugdex® - consultation on December 20087

Text book: Stockley Drug Interactions - 20068

Text book: Tatroo, D S - Drug interaction facts - 20079

Haagsma CJ. Clinically important drug interactions with Disease Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs - 199810

Lacaille D. Rheumatology: 8. Advanced Therapy - 200011

UpToDate - www.uptodate.com - consultation on December 200812

In the literature consulted, there is consensus regarding neither the drugs that interact with each of the antirheumatic drugs, nor the severity degree of the interaction. This review was aimed at reporting the maximum number of possible drug interactions according to the above-cited publications.

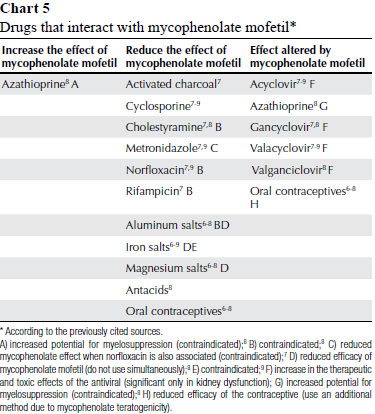

This study approached neither the intentional combination of drugs in the search for beneficial synergic effects, nor the interactions between drugs and vaccines. However, it reviewed the interactions that reduce the efficacy or increase the toxicity of one or both drugs, and those of greater clinical relevance were selected. The presentation order of the drugs did not follow a specific order of preference, but an alphabetical order/group: non-biological DMARDS and biological agents. The drugs and their possible interactions are shown in Charts 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.

AZATHIOPRINE

CHLOROQUINE/HYDROXYCHLOROQUINE

If the QT interval on the electrocardiogram (ECG) is excessively prolonged, ventricular arrhythmias, particularly polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, known as torsades de pointes, can occur. On ECG, that arrhythmia can appear as intermittent series of spikes, during which a failure in heart ejection occurs, blood pressure drops, and the patient feels dizzy and can lose consciousness. It is usually a self-limiting condition, but can degenerate into ventricular fibrillation, which can cause sudden death. There are innumerous causes for prolonged QT interval, such as congenital conditions, heart disease, some metabolic disorders (hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia), but the most likely major cause of such alterations is drug use. The risk for prolonging the QT interval is uncertain and unpredictable, and, thus, several pharmaceutical laboratories and regulating agencies currently contraindicate the concomitant use of drugs with a known potential for prolonging the QT interval due to the additive potential of that property. The University of Arizona, aware of the relevance of the issue, provides up-to-date lists of drugs that can prolong the QT interval,13 classifying those drugs as follows:

RISK OF TORSADES: drugs generally accepted to carry a risk of torsades de pointes: amiodarone,7,8 amitriptyline,7 clarithromycin,7,8 chlorpromazine,7,8 disopyramide,7 erythromicin,7,8 haloperidol,7,8 imipramine,7,8 nortriptyline,7 pentamidine,7,8 pimozide,7,8 quinidine,7,8 sotalol,7,8 thioridazine.7

POSSIBLE RISK OF TORSADES: drugs that can prolong the QT interval, but at this time lack substantial evidence for causing torsades de pointes: dolasetron,7 gatifloxacin,8 isradipine,7 moxifloxacin,8 octreotide,7 quetiapine,7 risperidone,7 tacrolimus,8 tamoxifen,8 telithromycin,7 ziprasidone.7

CONDITIONAL RISK OF TORSADES: drugs whose use should be avoided in patients diagnosed with or suspected of having the congenital long QT syndrome: fluconazole,7 fluoxetine,7 trimethoprim.7

The drugs that do not fit to any of the three classifications above, but that are reported in the above-cited sources of this review study as drugs that can interact with chloroquine resulting in an increased risk for prolonging the QT interval were classified as of UNDETERMINED RISK: enflurane,7 spiramycin,7,8 halothane,7 isoflurane,7 propafenone,7 trifluoperazine,7 vasopressin,7,8 zolmitriptan.7

Chloroquine is accepted by the QTdrugs.org Advisory Board of the Arizona CERT to carry a risk of torsades de pointes and, thus, its use is not recommended in association with other drugs with potential for the same alteration, thus increasing its cardiotoxicity unpredictably. Other drug interactions of chloroquine are shown in Chart 2.

CYCLOPHOSPHAMIDE

METHOTREXATE

MYCOPHENOLATE MOFETIL

BIOLOGICAL DRUGS (ADALIMUMAB, ETANERCEPT, AND INFLIXIMAB)

The drug interactions related to the use of the biological agents adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab should be considered, because there is an increase in the risk of severe infections when those agents are administered in association with abatacept,7,12 anakinra7,12 or rilonacept.7,12 Based on such interactions, the associated use of such drugs is not recommended. In addition, the concomitant use of etanercept and cyclophosphamide has been reported to be associated with an increase in the risk of developing non-cutaneous solid tumors, contraindicating the simultaneous use of those drugs. Although the clinical significance of the interaction has not yet been well assessed, an increase in the risk of neutropenia as an adverse effect of etanercept used simultaneously with sulfasalazine has been reported.12

DRUGS THAT DO NOT ALTER THE EFFECT OF ANTIRHEUMATIC DRUGS AND WHOSE EFFECTS ARE NOT ALTERED BY ANTIRHEUMATIC DRUGS

Safety reports on the simultaneous administration of drugs are scarce. Most of them are pharmacokinetic studies with a small number of patients, and assess the existence of an alteration in the safety profile of each drug when concomitantly used. The sources consulted suggest the concomitant use of the following drugs as safe:

Chloroquine: oral contraceptives;8 hypoglycemic agents;8 ranitidine.8

Cyclophosphamide: barbiturates,8 benzodiazepines,8 docetaxel,8 etoposide,8 famotidine,8 megestrol,8 ranitidine,8,10 sulfonamides,9 sulfadiazine,9 sulfamethoxazole.9

Methotrexate: acetaminophen,8 celecoxib,8 etoposide,8 meloxicam.8

Mycophenolate mofetil: allopurinol,8 gancyclovir (the simultaneous use of mycophenolate mofetil and gancyclovir is not safe in the presence of kidney dysfunction),7 methotrexate,8 voriconazole.8

Etanercept: digoxin.8

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

It is almost impossible to remember all known drug interactions, even when referring to the drugs used within a specialty, such as rheumatology. According to the WHO's Guide to Good Prescribing: a practical manual14, a treatment to be applied should be chosen based on efficacy, safety, applicability, and cost. That manual teaches how to choose and not what to choose. This study approaches not the efficacy of the drugs, but the second criterion for choosing the drugs, safety. In reality, this study assesses the safety of drug combination. Not all damage caused by drugs or drug combination can be avoided, but, since most harm results from the inadequate selection of the combinations, it can be prevented. For several inadequate associations, high risk groups can be identified. Usually, those are exactly the groups of patients who should be carefully considered: elderly, children, pregnant women, and individuals with kidney or liver disease. Such patients can have alterations in both the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the drugs administered.

According to the Guide to Good Prescribing, step 5, information, instructions, and warnings should be provided to patients. This study highlights the need for providing the patient with information about the signs and symptoms of possible drug interactions, considering that drug interaction is unpredictable. A practical solution would be to choose an alternative with no interaction, but, if none is available or possible, sometimes drugs that interact with each other can be prescribed when adequate precautions are taken. If the effects of the interactions are well monitored, they can often be allowed, usually with dose adjustment. Many interactions are dose-related, as can be observed with the drugs approached in this study: the use of the same drug for oncological purpose and its use at reduced doses for antirheumatic purposes differ. For example, dipyrone can increase the toxicity of high doses of methotrexate, but does not seem to have a similar effect on the methotrexate doses used for rheumatic diseases. Low doses of methotrexate do not seem to interact with carbamazepine, while high doses seem to do so.8

Some drug interactions can be prevented by using another member of the same group of drugs, such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. The potential of the former to prolong the QT interval on ECG, causing consequent life-threatening arrhythmias, does not recommend its use in association with other drugs with the same potential (antiarrhythmic drugs, anti-infectious agents, azole antifungals, quinolones, aminoglycosides, tricyclic antidepressants and SSRI, antipsychotics).13 Cimetidine and ranitidine, both H2 receptor antagonists, have a very different interaction profile.

It is worth emphasizing the following: immunosuppressants are drugs with a low therapeutic index; several frequently used drugs are enzyme inducers or inhibitors, and, thus, can alter the serum concentration of other substances or metabolites (active-toxic); and, finally, elderly patients, those with cardiac, liver or kidney dysfunction, and those submitted to polypharmacy are more susceptible to drug interactions.

Thus, a large number of drugs with potential for interaction can be safely administered when precautions are taken. That is step 6 of the Guide to Good Prescribing: monitor the treatment. The next step is: keep up-to-date about drugs!

For preventing adverse reactions consequent to drug interactions, the following is proposed:

Know the interaction potential of the drugs (be it with other drugs, foods, tobacco or alcohol) most commonly prescribed in a specialty.

Establish a way of gathering information about the drugs used by the patient (prescribed by other professionals or used in the form of self-medication). Would it not be useful if each patient were educated to carry along a prescription card that would be presented and whose filling should be required to every professional involved with the patient's care?

One limitation of our study is the number of sources researched. The study was not aimed at fully covering the issue, but at providing a contribution to rheumatology professionals involved with the responsible health care of patients with chronic diseases that require complex therapies.

REFERENCES

-

1Hoefler R. Interações medicamentosas: Formulário Terapêutico Nacional 2008. Série B. Textos Básicos de Saúde. Brasília (Brasil). Ministério da Saúde, 2008. 30-3 p. Disponível em http://www.opas.org.br/medicamentos/ [Acesso em 05 de dezembro de 2008]

-

2Cruciol-Souza JM, Thompson JC. A pharmacoepidemiologic study of drug interactions in a Brazilian teaching hospital. Clinics 2006; 61(6):515-20.

-

3Brown CH. Overview of drug interactions. US Pharm. 2000; 25(5):HS3-HS30.

-

4Treharne GJ, Douglas KM, Iwaszko J, Panoulas VF, Hale ED, Mitton DL et al. Polypharmacy among people with rheumatoid arthritis: the role of age, disease duration and comorbidity. Musculoskeletal Care 2007; 5(4):175-90.

-

5Jankel CA, McMillan JA, Martin BC. Effect of drug interactions on outcomes of patients receiving warfarin or theophylline. Am J Hosp Pharm 1994; 51(5):661-6.

-

6Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos, Departamento de Assistência Farmacêutica e Insumos Estratégicos. Formulário terapêutico nacional 2008: Rename 2006 Série B. Textos Básicos de Saúde. Brasília (Brasil). Ministério da Saúde, 2008. 897 p. Disponível em http://www.opas.org.br/medicamentos/ [Acesso em 05 de dezembro de 2008]

-

7Micromedex® Healthcare Series [Internet database]. Greenwood Village, Colo: Thomson Reuters (Healthcare) Inc. Updated periodically. Disponível em https://www.thomsonhc.com/ [Acesso em 03 de dezembro de 2008]

-

8Baxter K, ed. Stockley's Drug Interactions: a source book of interactions, their mechanisms, clinical importance and management. 7th ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2006.

-

9Tatroo DS, ed. Drug interaction factsTM 2007. St Louis: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2007.

-

10Haagsma CJ. Clinically important drug interactions with Disease Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs. Drugs Aging 1998;13(4):281-9.

-

11Lacaille D. Rheumatology: 8. Advanced Therapy. Can Med Assoc J 2000; 163(6):721-8.

-

12UpToDate, Inc. Wolters Kluwer Health. Wolters Kluwer. Disponível em www.uptodate.com [Acesso em 05 de dezembro de 2008]

-

13Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics. Arizona CERT. Disponível em http://www.azcert.org/medical-pros/drug-lists/druglists.cfm [Acesso em 10 de dezembro de 2008]

-

14Organização Mundial de Saúde. Guide to good prescribing: a practical manual - Guia para a Boa Prescrição Médica. Buchweitz C, tradutora. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 1998. Apr. 124 p.

Drug interactions: a contribution to the rational use of synthetic and biological immunosuppressants

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

04 May 2011 -

Date of issue

Apr 2011

History

-

Received

22 Jan 2010 -

Accepted

14 Jan 2011