Abstracts

Introduction:

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a connective tissue disease of autoimmune nature characterized by the triad of vascular injury, autoimmunity (cellular and humoral) and tissue fibrosis. Autoantibodies do not seem to be simply epiphenomena, but are involved in disease pathogenesis. It is believed that the SSc-specific autoantibodies are responsible both for amplifying immune response and targeting cell types that are relevant in the pathophysiology of SSc.

Objectives:

To correlate the profile of the following specific autoantibodies: anti-centromere (ACA), anti-topoisomerase I (topo I) and anti-RNA polymerase III (RNAP III) with clinical and laboratory manifestations were observed in 46 patients with SSc in the Midwest region of Brazil.

Methods:

The occurrence of specific autoantibodies in 46 patients with SSc was investigated, correlating the type of autoantibody with clinical and laboratory manifestations found.

Results:

Among all patients evaluated, we found a predominance of females (97.8%), mean age 50.21 years old, Caucasian (50%), limited cutaneous SSc (47.8%), time of diagnosis between 5 and 10 years (50%), and disease duration of 9.38 years. According to the specific autoantibody profile, 24 patients were ACA-positive (52.2%), 15 were positive for anti-topo I (32.6%), and 7 showed positive anti-RNAP III (15.2%). The anti-topo I autoantibody correlated with diffuse scleroderma, with greater disease severity and activity, with worse quality of life measured by the SHAQ index, with a higher prevalence of objective Raynaud's phenomenon and digital pitting scars of fingertips. The ACA correlated with limited scleroderma, with earlier onset of disease, as well as higher prevalence of telangiectasias. The anti-RNAP III correlated with diffuse scleroderma, with a higher occurrence of subjective Raynaud's phenomenon and muscle atrophy. There was no association between the positivity for anti-topo I, ACA and anti-RNAP III antibodies and other variables related to laboratory abnormalities, as well as Rodnan skin score and skin, vascular, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, cardiopulmonary and renal manifestations.

Conclusions:

The clinical subtype of the disease and some clinical manifestations in SSc may correlate positively with the presence of specific autoantibodies.

Autoantibodies; Systemic sclerosis; Anti-topoisomerase I; Anti-centromere; Anti-RNA polymerase III

Introdução:

a esclerose sistêmica (ES) é uma enfermidade do tecido conjuntivo de caráter autoimune caracterizada pela tríade de injúria vascular, autoimunidade (celular e humoral) e fibrose tecidual. Os autoanticorpos não parecem ser simplesmente epifenômenos, mas sim estarem envolvidos na patogênese da doença. Acredita-se que os autoanticorpos específicos da ES são responsáveis tanto pela amplificação da resposta imune quanto por alvejar os tipos celulares que são relevantes na fisiopatologia da ES.

Objetivos:

correlacionar o perfil de autoanticorpos específicos (anti-SCL70, ACA, anti-POL3) com as manifestações clínicas e laboratoriais observadas em 46 pacientes com ES da região Centro-Oeste do Brasil.

Métodos:

pesquisou-se a ocorrência de autoanticorpos específicos em 46 pacientes com diagnóstico de ES e correlacionou-se o tipo de autoanticorpo com as manifestações clínicas e laboratoriais encontradas.

Resultados:

dentre todos os pacientes avaliados, encontrou-se predomínio feminino (97,8%), idade média de 50,21 anos, cor branca (50%), forma limitada da doença (47,8%), tempo de diagnóstico entre cinco e 10 anos (50%) e tempo de evolução da doença de 9,38 anos. De acordo com o autoanticorpo específico, 24 pacientes apresentavam ACA positivo (52,2%), 15 apresentavam positividade para anti-SCL70 (32,6%) e sete apresentavam anti-POL3 positivo (15,2%). O autoanticorpo anti-SCL70 se correlacionou com a forma difusa da doença, com maior gravidade e atividade da doença, com pior qualidade de vida medida pelo índice HAQ, com maior prevalência de fenômeno de Raynaud objetivo e microcicatrizes de polpas digitais. O ACA se correlacionou com a forma limitada da doença, com o início mais precoce da enfermidade, bem como com maior prevalência de telangiectasias nos pacientes. Já o anti-POL3 se correlacionou com a forma difusa da doença, com maior ocorrência de fenômeno de Raynaud subjetivo e de atrofia muscular. Para as demais variáveis relacionadas às alterações laboratoriais, bem como em relação ao escore cutâneo de Rodnan e às manifestações cutâneas, vasculares, musculoesqueléticas, gastrintestinais, cardiopulmonares e renais, não houve associação entre elas e a positividade para os anticorpos anti-SCL70, ACA e anti-POL3.

Conclusões:

a forma clínica da doença e algumas manifestações clínicas na ES podem se correlacionar positivamente com a presença de autoanticorpos específicos.

Autoanticorpos; Esclerose sistêmica; Antitopoisomerase I; Anticentrômero; Anti-RNA polimerase III

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a connective tissue disease of autoimmune nature, extremely heterogeneous in its clinical presentation, with involvement of multiple systems, and following a variable and unpredictable course.11 Varga J, Abraham D. Systemic sclerosis: a prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:557–67. Its etiology remains unknown, with a multifactorial cause being suggested, possibly triggered by environmental factors in a genetically predisposed individual.22 Herrick AL, Worthington J. Genetic epidemiology systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res. 2002;4:165–8.

The hallmark of SSc is microvasculopathy, activation of fibroblasts and excessive collagen production.33 Coral-Alvarado P, Pardo AL, Castaño-Rodriguez N, Rojas-Villarraga A, Anaya JM. Systemic sclerosis: a worldwide global analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:757–65. It is a unique disease as it has features of three distinct pathophysiological processes; it consists of the triad of vascular injury, autoimmunity (cellular and humoral) and tissue fibrosis, leading to involvement of skin, in addition to several internal organs such as lungs, heart, gastrointestinal tract, among others.33 Coral-Alvarado P, Pardo AL, Castaño-Rodriguez N, Rojas-Villarraga A, Anaya JM. Systemic sclerosis: a worldwide global analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:757–65.,44 Beyer C, Schett G, Gay S, Distler O, Distler JHW. Hypoxia in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:220.

It is believed that the link between initial vascular involvement and the final consequence of the disease (tissue fibrosis) could be represented by autoimmunity. Circulating antibodies, alteration of immune mediators and infiltration of mononuclear cells in affected organs represent a positive argument for the hypothesis that dysfunction of the immune system leads to illness.55 Abraham DJ, Krieg T, Distler J, Distler O. Overview of pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol. 2009;48:iii3–7.,66 Lafyatis R, York M. Innate immunity and inflammation in systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:617–22.

It is described that highly specific antibodies can be detected in the sera of virtually all patients with SSc.77 Kraaij MD, Van Laar JM. The role of B cells in systemic sclerosis. Biologics. 2008;2:389–95. A review article by Zimmermann and Pizzichini highlights that specific antibodies represent one of the hallmarks of the disease and constitute the most evident expression of the involvement of the humoral immune system in the genesis of SSc.88 Zimmermann AF, Pizzichini MMM. Atualização na etiopatogênese da esclerose sistêmica. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2013;53:516–24. These autoantibodies have fundamental characteristics of a response triggered by the antigen, being mainly represented by: centromere antibodies (ACA), anti-DNA topoisomerase I (anti-topo I), and anti-RNA antibodies polymerase III (anti-RNAP III).99 Andrade LEC, Leser PG. Autoanticorpos na esclerose sistêmica (ES). Rev Bras Reumatol. 2004;44:215–23.–1212 Hamaguchi Y. Autoantibody profiles in systemic sclerosis: predictive value for clinical evaluation and prognosis. J Dermatol. 2010;37:42–53.

Recent studies highlight the pathogenic potential of autoantibodies in SSc patients, suggesting that specific antibodies against fibroblasts, endothelial cells and receptors for platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) can directly cause activation of fibroblasts and endothelial cells and contribute to tissue damage.11 Varga J, Abraham D. Systemic sclerosis: a prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:557–67.,1313 Salojin KV, Tonquèze ML, Saraux A, Nassonov EL, Dueymes M, Piette JC, et al. Antiendothelial cell antibodies: useful markers of systemic sclerosis. Am J Med. 1997;102:178–85.,1414 Baroni SS, Santillo M, Bevilacqua F, Luchetti M, Spadoni T, Mancini M, et al. Stimulatory autoantibodies to the PDGF receptor in systemic sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2667–76.

There is evidence to support the idea that the complexity of the SSc seems to

represent another collection of phenotypes compared to a single disease entity.

Thus, these genetic associations may actually be related to distinct phenotypes

in the SSc based on a pattern of autoantibodies.1515 Mayers MD, Trojanowska M. Genetic factors in systemic sclerosis.

Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(2). S5 (doi: 10.1186/ar2189).

https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2189...

The region of the HLA genes is a clear example of genetic polymorphism in the

development of SSc.1515 Mayers MD, Trojanowska M. Genetic factors in systemic sclerosis.

Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(2). S5 (doi: 10.1186/ar2189).

https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2189...

HLA association

studies were very inconsistent when patients were grouped by race or

ethnicity.1515 Mayers MD, Trojanowska M. Genetic factors in systemic sclerosis.

Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(2). S5 (doi: 10.1186/ar2189).

https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2189...

,1616 Romano E, Manetti M, Guiducci S, Ceccarelli C, Allanore Y,

Matucci-Cerinic M. The genetics of systemic sclerosis: an update. Clin Exp

Rheumatol. 2011;29:S75–86. However, when patients with SSc were

grouped according to the autoantibody profile, the findings were consistent

across the different ethnic groups.1515 Mayers MD, Trojanowska M. Genetic factors in systemic sclerosis.

Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(2). S5 (doi: 10.1186/ar2189).

https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2189...

For

example, HLA-DRB1*01–DQB1*0501 are more common in patients with ACA-positive SSc

while haplotypes HLA-DRB1*11–DQB1*0301 have been associated with the positivity

of anti-topo I antibodies.1616 Romano E, Manetti M, Guiducci S, Ceccarelli C, Allanore Y,

Matucci-Cerinic M. The genetics of systemic sclerosis: an update. Clin Exp

Rheumatol. 2011;29:S75–86.

The mechanisms postulated for the development of autoantibodies in SSc patients include: molecular mimicry, chronic hyper-reactivity of B lymphocytes from intrinsic abnormalities of the cell and increased expression, or altered subcellular localization of potentially auto-antigenic peptides.11 Varga J, Abraham D. Systemic sclerosis: a prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:557–67. Some antibodies do not appear to be simply epiphenomena, but to be involved in disease pathogenesis,1717 Feghali-Bostwick CA, Wilkes DS. Autoimmunity in idiopathic pulmonar fibrosis. Are circulating autoantibodies pathogenic or epiphenomena? Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2011;183:692–3. possibly by amplifying the immune response and targeting cell types that are relevant in the pathophysiology of the disease.1818 Gabrielli A, Svegliati S, Moroncini G, Avvedimento EV. Pathogenic autoantibodies in systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:640–5.

The importance of the study of autoantibodies in SSc lies in the fact that some of them have association with the disease and participate in the criteria proposed by LeRoy and Medsger for early diagnosis of the condition, which gives them considerable diagnostic value.99 Andrade LEC, Leser PG. Autoanticorpos na esclerose sistêmica (ES). Rev Bras Reumatol. 2004;44:215–23.,1010 Ho KT, Reveille JD. The clinical relevance of autoantibodies in scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:80–93.,1919 Vilas AP, Veiga MZ, Abecasis P. Esclerose sistémica – Perspectivas actuais. Med Interna. 2002;9:111–20. Moreover, they are associated with certain phenotypic traits of the disease, and are used to aid in the classification and characterization of two major disease subtypes: diffuse cutaneous SSc and limited cutaneous SSc.1010 Ho KT, Reveille JD. The clinical relevance of autoantibodies in scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:80–93.,2020 Freire EAM, Ciconelli RM, Sampaio-Barros PD. Análise dos critérios diagnósticos, de classificação, atividade e gravidade de doença na esclerose sistêmica. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2004;44:40–5. Also, a close relationship between levels of anti-topo I and severity of skin involvement and global disease activity in SSc was observed, revealing a possible prognostic role.1010 Ho KT, Reveille JD. The clinical relevance of autoantibodies in scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:80–93.,2121 Sato S, Hamaguchi Y, Hasegawa M, Takehara K. Clinical significance of anti-topoisomerase I antibody levels determined by Elisa in systemic sclerosis. Rheum. 2001;40:1135–40. In addition, significant correlations between the pattern of antibody profile presented and the therapeutic response have been reported.2222 Sharp GC, Irvin WS, LaRoque RL, Velez C, Daly V, Kaiser AD, et al. Association of autoantibodies to diferente nuclear antigens with clinical patterns of rheumatic disease and responsiveness to therapy. J Clin Inv. 1971;50:350–9.

Objectives

To correlate the profile of specific autoantibodies (ACA, anti-topo I and anti-RNAP III) with clinical manifestations observed in 46 patients with SSc followed in a university center from the Midwest region of Brazil.

Methods

This is an observational study of cross-sectional design, with prospective analysis of patient data.

A random selection of 46 patients was carried out from a survey of the medical records of the Department of Rheumatology of the University Hospital of the School of Medicine of the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (FMUFMS).

The patients were divided into three groups, according to the positivity of one of the specific autoantibodies (ACA, anti-topo I and anti-RNAP III).

Patients should meet the following inclusion criteria:

-

Meet the 2013 new classification Criteria for SSc;2323 Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1747–55.

-

In cases of absence of skin thickening, they should meet the 2001 LeRoy and Medsger's criteria of early SSc;2424 LeRoy EC, Medsger TA Jr. Criteria for the classification of early systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1573–6.

-

They should have signed a Consent Form previously approved by the Research Ethics Committee of UFMS.

-

Patients who presented with other associated infectious diseases or malignancies were excluded.

The socio-demographic and clinical information was obtained from the patient medical records and complemented with two interviews, within a time interval of 6 months. In the first appointment, demographic and clinical data were collected, including disease duration, year of diagnosis, modified Rodnan skin score,2525 Valentini G, D’Angelo S, Rossa AD, Bencivelli W, Bombardieri S. European Scleroderma Study Group to define disease activity criteria for systemic sclerosis. IV. Assessment of skin thickening by modified Rodnan skin score. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:904–5. autoantibodies test, thorough clinical examination and current treatment.

Disease duration was divided into two: total time in years of Raynaud's phenomenon (RP) before diagnosis of the disease (RP time) and total time in years of clinical manifestations of the disease after diagnosis, not considering RP (time without RP).

Specific data about Medsger's Severity Criteria2626 Medsger TA Jr. Natural history of systemic sclerosis and the assessment of disease activity, severity, functional status, and psychologic well-being. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2003;29:255–73. and Valentini's Criteria of Activity2727 Valentini G, Silman AJ, Veale D. Assessment of disease activity. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21:S39–41. were collected on specific formularies at baseline assessment and after 6 months. The Scleroderma Health Assessment Questionnaire (SHAQ)2828 Rannou F, Poiraudeau S, Berezné A, Baubet T, Le-Guern V, Cabane J, et al. Assessing disability and quality of life in systemic sclerosis: construct validities of the Cochin hand function scale, health assessment questionnaire (HAQ), systemic sclerosis HAQ, and medical outcomes study 36-item short form health survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:94–102. was also collected in the initial patient assessment and on second assessment.

SHAQ is a measure of function in SSc, being a helpful tool for the assessment of physical functional disability2929 Georges C, Chassany O, Mouthon L, Tiev K, Toledano C, Meyer O, et al. Validation of French version of the Scleroderma Health Assessment Questionnaire (SSc HAQ). Clin Rheumatol. 2005;24:3–10. and the impact of the disease on patient's physical and mental well-being.3030 Xinyi NG, Thumboo J, Low AHL. Validation of the scleroderma health assessment questionnaire and quality of life in English and Chinese-speaking patients with systemic sclerosis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15:268–76. The objective was to correlate if the rate of disability measured by SHAQ would be higher in one of the three groups of patients with specific autoantibodies (ACA, anti-topo I and anti-RNAP III).

Sera properly frozen at −50 °C and stored at the Laboratory of the University Hospital of UFMS from previously selected patients was used for performing the research.

-

(a) For the examination of anti-centromere (ACA) – we used the indirect immunofluorescence technique and having HEp2 cells as substrate according to the criteria of the II Brazilian Consensus of antinuclear antibody in Hep-2 (2003) cells,3131 Dellavance A, Gabriel A Jr, Cintra AFU, Ximenes AC, Nuccitelli B, Tabilerti BH, et al. II Consenso Brasileiro de Fator Antinuclear em células Hep-2. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2003;43:129–40. for the interpretation of results.

-

(b) For the examination of anti-DNA topoisomerase 1 (anti-topo I) – enzyme immunoassay technique was used,2121 Sato S, Hamaguchi Y, Hasegawa M, Takehara K. Clinical significance of anti-topoisomerase I antibody levels determined by Elisa in systemic sclerosis. Rheum. 2001;40:1135–40. being non-reactive if <20 units, weakly positive between 20 and 39 units, moderately positive between 40 and 80 units and strongly positive if >80 units. A specific kit QUANTA Lite TM Scl-70 was used from Laboratory INOVA (INOVA Diagnostics, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), following the manufacturer's specifications.

-

(c) Anti-RNA polymerase III (anti-RNAP III) antibody – examinations were performed in duplicate using ELISA technique, as previously described.3232 Codullo V, Morozzi G, Bardoni A, Salvini R, Deleonardi G, Pità O, et al. Validation of a new immunoenzymatic method to detect antibodies to RNA polymerase III in systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:373–7. Values <20 units were considered negative, weakly positive if between 20 and 39 units, moderately positive if between 40 and 80 units and strongly positive if >80 units.

Statistical analysis

Comparison of patients with positive anti-topo I antibody, ACA or anti-RNAP III in relation to the quantitative variables evaluated in this study was performed by one-way ANOVA.

The chi-square test was used to assess the association between the results for the antibodies (ACA, anti-topo I and anti-RNAP III), with qualitative variables measured in this study. The results of the other variables were presented in the form of descriptive statistics or in the form of tables and graphs. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 20.0, considering a significance level of 5%.

Results

Of the 46 patients included, 45 were women (97.8%) and 1 was a man (2.2%), with a mean age of 50.21 ± 3.55 years (mean ± standard error).

The race of the patients was as follows: 23 patients were classified as Caucasians (50.0%), 21 as mixed (45.7%) and 2 patients, black (4.3%).

Regarding the diagnosis, 42 diagnosed patients met the 2013 ACR/EULAR classification Criteria for SSc (91.3%). The 4 patients (8.7%) who did not meet these criteria met LeRoy/Medsger's criteria for early SSc.

Regarding the clinical subtypes of the disease, 22 patients had limited cutaneous SSc (47.8%), 16 patients had the diffuse cutaneous SSc (34.8%), 3 patients had the early form (6.5%), 5 patients had overlap form (10.9%) and none had the Sine Scleroderma form. These results are shown in Fig. 1.

Percentage of patients with positive antibody to anti-topo I, ACA and anti-RNAP III among patients with different clinical subtypes of the disease. Each column represents the percent of patients. * Significant difference compared to patients with positive anti-topo I and anti-RNAP III, in limited scleroderma. ** Significant difference compared to patients with positive ACA, in diffuse scleroderma (chi-square test; p < 0.050).

Regarding time since diagnosis, 12 patients were diagnosed for more than 10 years (26.1%), 23 patients were diagnosed between 5 and 10 years (50.0%) and 11 patients were diagnosed for less than 5 years (23.9%).

The time for disease progression of patients in general was 9.38 ± 3.08 years.

Among all patients, 24 showed positive ACA (52.2%), 15 were positive for anti-topo I (32.6%) and 7 were positive for anti-RNAP III (15.2%).

Results regarding socio-demographic and clinical parameters in patients with positive ACA, anti-topo I or anti-RNAP III, are presented in Table 1.

Demographic and clinical features of patients with positive anti-topo I, ACA or anti-RNAP III antibodies.

There was no significant difference between patients with positive anti-topo I, ACA or anti-RNAP III antibodies in relation to the quantitative variables age, duration of RP before diagnosis, and duration of illness without counting RP. Moreover, SHAQ of patients with positive anti-topo I was significantly higher than that for patients with positive ACA or anti-RNAP III antibody (p < 0.05). The same result was observed in relation to the scale of activity. Moreover, SHAQ among patients with positive ACA or anti-topo I was higher than that for patients with positive anti-RNAP III antibody (p < 0.05).

For the scale of severity, the score among patients with positive anti-topo I antibody was higher than that for patients with positive ACA antibody (p < 0.05), but with no difference for patients with positive anti-RNAP III antibody (p > 0.05). There was no further association between positive anti-topo I, ACA or anti-RNAP III antibodies and nominal or ordinal qualitative variables of gender, race, time since diagnosis and 2013 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for SSc. However, there was an association between positive anti-topo I, ACA or anti-RNAP III antibodies and the clinical subtype of the disease (p < 0.001), with the percentage of patients with limited disease among patients with positive ACA antibody (83, 3%, n = 20) being significantly higher than that among patients with positive anti-topo I and anti-RNAP III antibody (0.0%, n = 0 and 28.6%, n = 2, respectively). On the other hand, the percentage of patients with diffuse disease, among patients with positive anti-topo I and anti-RNAP III (86.7%, n = 13 and 42.9%, n = 3), respectively, was significantly higher than that among patients with positive ACA (0.0%, n = 0) antibody.

Table 2 shows the results for the skin, vascular and musculoskeletal manifestations in patients with a positive result for anti-topo I, ACA and anti-RNAP III antibodies. In this evaluation, it was observed that the percentage of patients with positive anti-topo I antibody, which had objective RP (93.3%, n = 14) was significantly higher than that of patients with positive anti-RNAP III antibody, which also showed objective RP (42.9%, n = 3, p < 0.05). On the other hand, the percentage of patients with positive anti-RNAP III antibody, who had subjective RP (57.1%, n = 4), was significantly higher than that of patients with positive anti-topo I antibody, which also showed subjective RP (6.7%, n = 1).

Distribution of patients according to the skin, vascular and musculoskeletal manifestations in patients with positive anti-topo I, ACA or anti-RNAP III antibodies.

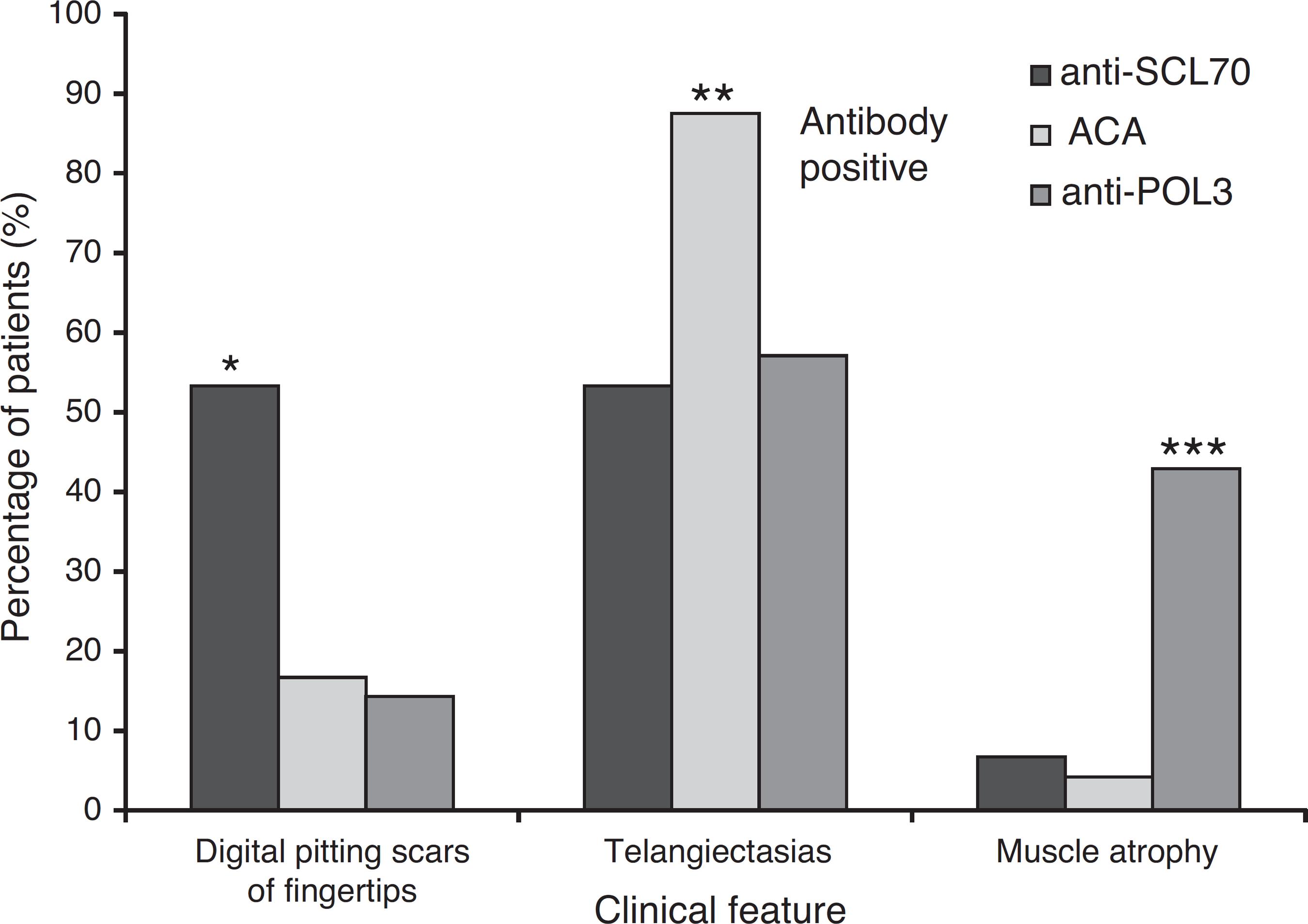

Patients with positive anti-topo I antibody showed more digital pitting scars of fingertips than patients with positive ACA antibody (p < 0.05). Furthermore, patients with positive ACA antibody had more telangiectasia than patients with positive anti-topo I antibody (p < 0.050). Furthermore, patients with positive anti-RNAP III antibody had more muscle atrophy than patients with positive ACA antibody (p < 0.050). These results are presented in Fig. 2. For the other variables related to skin, vascular and musculoskeletal manifestations, there was no association between them and the positivity for anti-topo I, ACA and anti-RNAP III antibodies. There was also no significant difference between patients with positivity for these three antibodies in relation to skin score (p = 0.065).

Percentage of patients with clinical manifestations such as digital pitting scars of fingertips, telangiectasias and muscle atrophy, among patients with positive anti-topo I, ACA and anti-RNAP III. Each column represents the percent of patients. * Significant difference compared to patients with positive ACA and anti-RNAP III. ** Significant difference compared to patients with positive anti-topo I and anti-RNAP III. *** Significant difference compared to patients with positive anti-topo I and ACA (chi-square test; p < 0.050).

The results related to gastrointestinal, cardiopulmonary and renal manifestations in patients with positive anti-topo I, ACA or anti-RNAP III are presented in Table 3. There was no association between the presence of autoantibodies specific for SSc and the variables studied.

Distribution of patients according to gastrointestinal, cardiopulmonary and renal manifestations in patients with positive anti-SCL70, ACA or anti-POL3.

The results of the laboratory tests (ESR, CRP, CPK, creatinine, C3 and C4), antibody tests (anti-Ro, anti-La, anti-Sm, anti-RNP and anti Jo-1) and changes observed on hand radiographs in patients with positive anti-topo I, ACA and/or anti-RNAP III antibodies are shown in Table 4, where a lack of statistical significance for all the studied parameters can be seen.

Distribution of patients according to the laboratory tests in patients with anti-topo I, ACA or anti-RNAP III positive.

Discussion

In our study, a unique sample was defined that was representative of the Midwest region of Brazil, characterized by a heterogeneous group of patients with various spectrums of disease and different stages of clinical manifestations and disease activity, but that is very similar to other patient populations in the country and even from other locations.3333 Skare TL, Luciano AC, Fonseca AE, Azevedo PM. Autoanticorpos em esclerodermia e sua associação ao perfil clínico da doença. Estudo em 66 pacientes do sul do Brasil. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1075–81.–3838 Guidolim F, Esmanhotto L, Magro CE, Silva MB, Skare TL. Prevalência de achados cutâneos em portadores de esclerose sistêmica – Experiência de um hospital universitário. An Bras Dermatol. 2005;80:481–6.

This study objective was to investigate the correlation between the profile of specific autoantibodies (ACA, anti-topo I or anti-RNAP III) and clinical and laboratory manifestations in this population of patients with SSc. Similar to other populations, our patients were mostly female (97.83%) and with limited scleroderma (47.8%), with a mean age of 50 years and caucasian (50.0%). In 65% of the patients, RP was the first disease manifestation before diagnosis, time since diagnosis occurred mainly between 5 and 10 years (50.0%), mean disease duration of 9 years, and average modified Rodnan skin score of 13.66. Regarding specific antibodies, 52.2% of the patients had positive ACA, 32.6% were positive for anti-topo I and 15.2% were positive for anti-RNAP III.

In Brazil, recently two different groups of researchers in the southern region described the occurrence of major specific autoantibodies in patients with SSc and both authors highlighted the importance of autoantibodies in the evaluation of patients with SSc.3333 Skare TL, Luciano AC, Fonseca AE, Azevedo PM. Autoanticorpos em esclerodermia e sua associação ao perfil clínico da doença. Estudo em 66 pacientes do sul do Brasil. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1075–81.,3434 Müller CS, Paiva ES, Azevedo VF, Radominski SC, Lima Filho JHC. Perfil de autoanticorpos e correlação clínica em um grupo de pacientes com esclerose sistêmica na região Sul do Brasil. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2011;51:319–24.

The first group from Hospital Evangélico de Curitiba (HUEC) found, in 66 SSc patients, the prevalence of ACA, anti-topo I and anti-U1-RNP, respectively in 33.3%, 17.8% and 11.8% of patients.3333 Skare TL, Luciano AC, Fonseca AE, Azevedo PM. Autoanticorpos em esclerodermia e sua associação ao perfil clínico da doença. Estudo em 66 pacientes do sul do Brasil. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1075–81. Although the percentage of each autoantibody found in our study is greater for ACA and anti-topo I, the order of distribution among specific autoantibodies was identical. The authors from HUEC also observed an association of anti-topo I with diffuse scleroderma and digital pitting scars of fingertips; however, they found an association between this autoantibody and the presence of cardiomyopathy. Unlike our study, ACA was protective for cardiomyopathies and anti-U1-RNP was more common in overlap forms.3333 Skare TL, Luciano AC, Fonseca AE, Azevedo PM. Autoanticorpos em esclerodermia e sua associação ao perfil clínico da doença. Estudo em 66 pacientes do sul do Brasil. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1075–81.

The second group from Hospital de Clínicas of the Federal University of the state of Paraná (HC-UFPR) investigated the prevalence of anti-RNAP III, anti-topo I and ACA in 85 SSc patients and found their presence in 41.18%; 31.76% and 30.59% of patients, respectively.3434 Müller CS, Paiva ES, Azevedo VF, Radominski SC, Lima Filho JHC. Perfil de autoanticorpos e correlação clínica em um grupo de pacientes com esclerose sistêmica na região Sul do Brasil. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2011;51:319–24. Although it was noted that the limited form was the most prevalent among patients, this study found very high prevalence of positive anti-RNAP III, which is related to diffuse cutaneous SSc. Our study has validated the same clinical features observed in the group of patients from HC-UFPR who were anti-topo I-positive, such as association with diffuse scleroderma, the presence of active disease and digital ulcers. However, the group from HC-UFPR found an association between synovitis and positivity for anti-RNAP III, and greater prevalence of systemic hypertension and cardiac conduction block in patients with positive ACA.3434 Müller CS, Paiva ES, Azevedo VF, Radominski SC, Lima Filho JHC. Perfil de autoanticorpos e correlação clínica em um grupo de pacientes com esclerose sistêmica na região Sul do Brasil. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2011;51:319–24.

In the present work, ACA was mainly correlated with limited cutaneous SSc, with earlier onset of disease, as well as higher prevalence of telangiectasias. ACA was found in 52.2% of patients and, in the literature, ACAs were observed in about 20–30% of patients with SSc1010 Ho KT, Reveille JD. The clinical relevance of autoantibodies in scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:80–93.,1212 Hamaguchi Y. Autoantibody profiles in systemic sclerosis: predictive value for clinical evaluation and prognosis. J Dermatol. 2010;37:42–53. and in 55–80% of patients with the limited form99 Andrade LEC, Leser PG. Autoanticorpos na esclerose sistêmica (ES). Rev Bras Reumatol. 2004;44:215–23., although it can vary among different ethnic populations.1010 Ho KT, Reveille JD. The clinical relevance of autoantibodies in scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:80–93.,1212 Hamaguchi Y. Autoantibody profiles in systemic sclerosis: predictive value for clinical evaluation and prognosis. J Dermatol. 2010;37:42–53. ACAs have predictive value for future development of SSc in patients with RP and are associated with limited cutaneous involvement, peripheral vascular damage and calcinosis.1010 Ho KT, Reveille JD. The clinical relevance of autoantibodies in scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:80–93.,1212 Hamaguchi Y. Autoantibody profiles in systemic sclerosis: predictive value for clinical evaluation and prognosis. J Dermatol. 2010;37:42–53. However, no greater prevalence of calcinosis in our patients with the limited form was observed. The presence of ACA generally provides a better prognosis than that seen with other antibodies, since they are less frequently associated with interstitial lung fibrosis,1010 Ho KT, Reveille JD. The clinical relevance of autoantibodies in scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:80–93.,1212 Hamaguchi Y. Autoantibody profiles in systemic sclerosis: predictive value for clinical evaluation and prognosis. J Dermatol. 2010;37:42–53. as observed in our study, although not achieving statistical significance.

In this study, the anti-topo I autoantibody was mainly correlated with the diffuse cutaneous SSc, with greater disease severity and activity, with worse quality of life as measured by SHAQ index, a higher prevalence of objective RP, and digital pitting scars of fingertips. We found anti-topo I in 32.6% of patients, in accordance with the literature, which describes this antibody in 40% of patients with SSc,1212 Hamaguchi Y. Autoantibody profiles in systemic sclerosis: predictive value for clinical evaluation and prognosis. J Dermatol. 2010;37:42–53. in about 28–70% patients with the diffuse cutaneous SSc99 Andrade LEC, Leser PG. Autoanticorpos na esclerose sistêmica (ES). Rev Bras Reumatol. 2004;44:215–23.,1010 Ho KT, Reveille JD. The clinical relevance of autoantibodies in scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:80–93.,1212 Hamaguchi Y. Autoantibody profiles in systemic sclerosis: predictive value for clinical evaluation and prognosis. J Dermatol. 2010;37:42–53. and in less than 10% of patients with limited scleroderma.98 Zimmermann AF, Pizzichini MMM. Atualização na etiopatogênese da esclerose sistêmica. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2013;53:516–24.–1111 Mouthon L, Pe˜na-Lefebvre PGL, Chanseaud Y, Tamby MC, Boissier MC, Gluillevin L. Sclérodermie (1 re partie). Ann Med Interne. 2002;153:167–78. As observed in our patients, it is described that ethnic differences significantly affect the prevalence of anti-topo I, and it is observed to a lesser extent in Caucasians. Anti-topo I, when determined by immunodiffusion, is virtually never seen in healthy individuals, in other diseases of the connective tissue, or in patients with primary RP.1010 Ho KT, Reveille JD. The clinical relevance of autoantibodies in scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:80–93.,1212 Hamaguchi Y. Autoantibody profiles in systemic sclerosis: predictive value for clinical evaluation and prognosis. J Dermatol. 2010;37:42–53. Its presence is described as related to worse prognosis, global disease activity, severity of skin involvement, interstitial lung disease and cardiac involvement.99 Andrade LEC, Leser PG. Autoanticorpos na esclerose sistêmica (ES). Rev Bras Reumatol. 2004;44:215–23.,1010 Ho KT, Reveille JD. The clinical relevance of autoantibodies in scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:80–93.,1212 Hamaguchi Y. Autoantibody profiles in systemic sclerosis: predictive value for clinical evaluation and prognosis. J Dermatol. 2010;37:42–53.,3939 Hu PQ, Fertig N, Medsger T Jr, Wright TM. Correlation of serum anti-DNA topoisomerase I antibody levels with disease severity and activity in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1363–73.–4141 Hu PQ, Hurwitz AA, Oppenheim JJ. Immunization with DNA topoisomerase I induces autoimune responses but not scleroderma-like pathologies in mice. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:2243–52. However, cardiopulmonary manifestations were not more prevalent or more severe in this study.

However, in this work, the anti-RNAP III was primarily correlated with diffuse

scleroderma, since other two patients with inflammatory myopathy-associated

positive anti-RNAP III had diffuse cutaneous involvement. Interestingly, both

patients with overlap were not positive for anti-Jo1 antibody. Moreover, we

observed a higher frequency of subjective RP and muscle atrophy in our patients.

We found anti-RNAP III in 15.2% of patients, but other published studies

describes a prevalence of this antibody at different frequencies, probably

related to genetic and racial differences. Its prevalence ranged from 4 to 9.4%

in French, 12% in English, 6% in Japanese, 19.4% in Canadian, and 25% in

American patients.99 Andrade LEC, Leser PG. Autoanticorpos na esclerose sistêmica (ES).

Rev Bras Reumatol. 2004;44:215–23.,4242 Nikpour M, Hissaria P, Byron J, Sahhar J, Micallef M, Paspaliaris W,

et al. Prevalence, correlates and clinical usefulness of antibodies to RNA

polymerase III in systemic sclerosis: a cross-sectional analysis of data from an

Australian cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13. R211. (doi:

http://arthritis-research.com/content/13/6/R211).

http://arthritis-research.com/content/13...

Autoantibodies against RNA polymerase 1

and 3 usually coexist in a prevalence of 20%, and this pattern is highly

specific for SSc.99 Andrade LEC, Leser PG. Autoanticorpos na esclerose sistêmica (ES).

Rev Bras Reumatol. 2004;44:215–23.,1010 Ho KT, Reveille JD. The clinical relevance of autoantibodies in

scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:80–93.,1212 Hamaguchi Y. Autoantibody profiles in systemic sclerosis: predictive

value for clinical evaluation and prognosis. J Dermatol.

2010;37:42–53. Anti-RNAP III also has a prognostic role, since it was

related to diffuse skin involvement, tendon friction rubs, and kidney

involvement,99 Andrade LEC, Leser PG. Autoanticorpos na esclerose sistêmica (ES).

Rev Bras Reumatol. 2004;44:215–23.,4242 Nikpour M, Hissaria P, Byron J, Sahhar J, Micallef M, Paspaliaris W,

et al. Prevalence, correlates and clinical usefulness of antibodies to RNA

polymerase III in systemic sclerosis: a cross-sectional analysis of data from an

Australian cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13. R211. (doi:

http://arthritis-research.com/content/13/6/R211).

http://arthritis-research.com/content/13...

,4343 Vanthuyne M, Smith V, De Langhe E, Praet JV, Arat S, Depresseux G,

et al. The Belgian systemic sclerosis cohort: correlations between disease

severity sclores, cutaneous subsets, and autoantibody profile. J Rheumatol.

2012;39:2127–33. but no scleroderma renal crisis was observed in our

patients. Besides myositis observed in our patients, studies published in the

literature highlights other significant associations between the positivity of

anti-RNAP III with the occurrence of synovitis and systemic hypertension, as

well as a possible relation to malignancies, predominantly solid organ

cancer.4242 Nikpour M, Hissaria P, Byron J, Sahhar J, Micallef M, Paspaliaris W,

et al. Prevalence, correlates and clinical usefulness of antibodies to RNA

polymerase III in systemic sclerosis: a cross-sectional analysis of data from an

Australian cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13. R211. (doi:

http://arthritis-research.com/content/13/6/R211).

http://arthritis-research.com/content/13...

,4343 Vanthuyne M, Smith V, De Langhe E, Praet JV, Arat S, Depresseux G,

et al. The Belgian systemic sclerosis cohort: correlations between disease

severity sclores, cutaneous subsets, and autoantibody profile. J Rheumatol.

2012;39:2127–33.

Unlike systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), the production of a specific autoantibody is unique in patients with SSc, so the occurrence of more than one type of antibody in a patient is rare, except for antibodies against RNA polymerase.99 Andrade LEC, Leser PG. Autoanticorpos na esclerose sistêmica (ES). Rev Bras Reumatol. 2004;44:215–23.,1010 Ho KT, Reveille JD. The clinical relevance of autoantibodies in scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:80–93.,1212 Hamaguchi Y. Autoantibody profiles in systemic sclerosis: predictive value for clinical evaluation and prognosis. J Dermatol. 2010;37:42–53. The coexistence of anti-topo I and ACA in SSc is uncommon (0.5–5.5%), although some authors have previously considered it mutually exclusive.4444 Rasco RG, Palma MJC, Hernández FJG, Román JS. Coexistencia de anticuerposanti-topoisomerase I y anticentrômero em la esclerodermia. Med Clín (Barc). 2010;135:430–1. Although the correlation between antibodies that define subtypes of SSc is unusual, the coexistence of ACA or anti-topo I with anti-histone antibodies, ACA with anti-mitochondrial antibodies, anti-topo I with anticardiolipin antibodies, ACA or anti-topo I with Ro (SSA) antibodies, or anti RNPs with anti Th/To antibodies was described.4545 Dick T, Mierau R, Bartz-Bazzanella P, Alavi M, Stoyanova-Scholz M, Kindler J, et al. Coexistence of anti-topoisomerase I and anticentromere antibodies in patients with systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:121–7. Our study observed the coexistence of positive anti-topo I and anti-RNAP III in a patient with diffuse scleroderma.

Based on SHAQ, this study observed higher scores of disability among patients

with positivity of anti-topo I, similar to those described in other populations

of patients with the diffuse form of SSc.2929 Georges C, Chassany O, Mouthon L, Tiev K, Toledano C, Meyer O, et

al. Validation of French version of the Scleroderma Health Assessment

Questionnaire (SSc HAQ). Clin Rheumatol. 2005;24:3–10.,4646 Morita Y, Muro Y, Sugiura K, Tomita Y, Tamakoshi K. Results of the

Health Assessment Questionnaire for Japanese patients with systemic sclerosis –

Measuring functional impairment in systemic sclerosis versus other connective

tissue diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:367–72.

Comparatively, Morita and colleagues reported that patients with the diffuse

form of SSc had higher rates of disability on the SHAQ, also higher than those

of patients with RA, SLE and other autoimmune diseases.4646 Morita Y, Muro Y, Sugiura K, Tomita Y, Tamakoshi K. Results of the

Health Assessment Questionnaire for Japanese patients with systemic sclerosis –

Measuring functional impairment in systemic sclerosis versus other connective

tissue diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:367–72. It was also observed that SSc patients with articular

involvement had higher scores on SHAQ than patients with psoriatic arthritis,

while the pain domain was higher in SSc patients than in RA patients.4747 Pope J. Measures of systemic sclerosis (Scleroderma). Arthritis Care

Res. 2011;63(S11):S98–111. Unpublished data of our patients confirm

the greater disability in the subgroup of patients with arthritis. Recently

Iudici and colleagues found that patients with early form of SSc, despite having

only RP, had already experienced an impairment of quality of life in both

physical and mental domains.4848 Iudici M, Cuomo G, Vettori S, Avellino M, Valentini G. Quality of

life as measured by the short-form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire in patients with

early systemic sclerosis and undifferentiated connective tissue disease. Health

Qual Life Out. 2013;11:23 (doi:

http://www.hqlo.com/content/11/1/23).

http://www.hqlo.com/content/11/1/23...

Accordingly, our 3 patients with the early form showed a disability index

measured by the SHAQ that was comparable to other groups. The usefulness of SHAQ

in the evaluation of patients with SSc has been demonstrated by studies that

reported that it can predict the evolution and survival in these patients.2929 Georges C, Chassany O, Mouthon L, Tiev K, Toledano C, Meyer O, et

al. Validation of French version of the Scleroderma Health Assessment

Questionnaire (SSc HAQ). Clin Rheumatol. 2005;24:3–10.,4949 Danieli E, Airò P, Bettoni L, Cinquini M, Antonioli CM, Cavazzana I,

et al. Health-related quality of life measured by the Short Form 36 (SF-36) in

systemic sclerosis: correlations with indexes of disease activity and severity,

disability, and depressive symptoms. Clin Rheumatol.

2005;24:48–54. In this work, there was a significant positive linear

correlation between SHAQ and disease activity as measured by the Pearson test.

Medsger and colleagues found that the rates of disability measured by SHAQ

showed strong correlation with skin thickening, cardiac involvement, digital

contractures, tendon friction rubs, and renal involvement in 1000 patients with

SSc.2626 Medsger TA Jr. Natural history of systemic sclerosis and the

assessment of disease activity, severity, functional status, and psychologic

well-being. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2003;29:255–73.

In conclusion, this study confirms the important role of specific autoantibodies in the evaluation of patients with SSc. It is possible to correlate the antibody profile of this national population with some distinct clinical manifestations of the disease.

Conclusions

We highlight, in agreement with the literature, that the clinical subtype of the disease and some clinical manifestations in SSc may correlate positively with the presence of specific autoantibodies.

The presence of ACA was observed, particularly in the early forms of the disease, limited scleroderma, and overlap syndrome, with absence in the diffuse scleroderma. The anti-topo I was mainly observed in the diffuse and overlap forms, being absent in the limited disease.

Patients with positive anti-topo I have higher disease activity and severity, and impairment in quality of life as measured by SHAQ index.

Anti-topo I-positive patients have more objective RP and digital pitting scars of fingertips, patients positive for ACA had more telangiectasia and patients with positive anti-RNAP III antibody had more muscle atrophy.

The specific autoantibodies may directly contribute to the patient's evolution and prognosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank their colleagues Dr Luis Eduardo Coelho Andrade and Dr. Cristiane Kayser for helping in the performance of anti-RNA Polymerase III tests, and to Dr. Natalino Yoshinari for his great incentive to their research.

Referências

-

1Varga J, Abraham D. Systemic sclerosis: a prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:557–67.

-

2Herrick AL, Worthington J. Genetic epidemiology systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res. 2002;4:165–8.

-

3Coral-Alvarado P, Pardo AL, Castaño-Rodriguez N, Rojas-Villarraga A, Anaya JM. Systemic sclerosis: a worldwide global analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:757–65.

-

4Beyer C, Schett G, Gay S, Distler O, Distler JHW. Hypoxia in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:220.

-

5Abraham DJ, Krieg T, Distler J, Distler O. Overview of pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol. 2009;48:iii3–7.

-

6Lafyatis R, York M. Innate immunity and inflammation in systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:617–22.

-

7Kraaij MD, Van Laar JM. The role of B cells in systemic sclerosis. Biologics. 2008;2:389–95.

-

8Zimmermann AF, Pizzichini MMM. Atualização na etiopatogênese da esclerose sistêmica. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2013;53:516–24.

-

9Andrade LEC, Leser PG. Autoanticorpos na esclerose sistêmica (ES). Rev Bras Reumatol. 2004;44:215–23.

-

10Ho KT, Reveille JD. The clinical relevance of autoantibodies in scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:80–93.

-

11Mouthon L, Pe˜na-Lefebvre PGL, Chanseaud Y, Tamby MC, Boissier MC, Gluillevin L. Sclérodermie (1 re partie). Ann Med Interne. 2002;153:167–78.

-

12Hamaguchi Y. Autoantibody profiles in systemic sclerosis: predictive value for clinical evaluation and prognosis. J Dermatol. 2010;37:42–53.

-

13Salojin KV, Tonquèze ML, Saraux A, Nassonov EL, Dueymes M, Piette JC, et al. Antiendothelial cell antibodies: useful markers of systemic sclerosis. Am J Med. 1997;102:178–85.

-

14Baroni SS, Santillo M, Bevilacqua F, Luchetti M, Spadoni T, Mancini M, et al. Stimulatory autoantibodies to the PDGF receptor in systemic sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2667–76.

-

15Mayers MD, Trojanowska M. Genetic factors in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(2). S5 (doi: 10.1186/ar2189).

» https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2189 -

16Romano E, Manetti M, Guiducci S, Ceccarelli C, Allanore Y, Matucci-Cerinic M. The genetics of systemic sclerosis: an update. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:S75–86.

-

17Feghali-Bostwick CA, Wilkes DS. Autoimmunity in idiopathic pulmonar fibrosis. Are circulating autoantibodies pathogenic or epiphenomena? Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2011;183:692–3.

-

18Gabrielli A, Svegliati S, Moroncini G, Avvedimento EV. Pathogenic autoantibodies in systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:640–5.

-

19Vilas AP, Veiga MZ, Abecasis P. Esclerose sistémica – Perspectivas actuais. Med Interna. 2002;9:111–20.

-

20Freire EAM, Ciconelli RM, Sampaio-Barros PD. Análise dos critérios diagnósticos, de classificação, atividade e gravidade de doença na esclerose sistêmica. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2004;44:40–5.

-

21Sato S, Hamaguchi Y, Hasegawa M, Takehara K. Clinical significance of anti-topoisomerase I antibody levels determined by Elisa in systemic sclerosis. Rheum. 2001;40:1135–40.

-

22Sharp GC, Irvin WS, LaRoque RL, Velez C, Daly V, Kaiser AD, et al. Association of autoantibodies to diferente nuclear antigens with clinical patterns of rheumatic disease and responsiveness to therapy. J Clin Inv. 1971;50:350–9.

-

23Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1747–55.

-

24LeRoy EC, Medsger TA Jr. Criteria for the classification of early systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1573–6.

-

25Valentini G, D’Angelo S, Rossa AD, Bencivelli W, Bombardieri S. European Scleroderma Study Group to define disease activity criteria for systemic sclerosis. IV. Assessment of skin thickening by modified Rodnan skin score. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:904–5.

-

26Medsger TA Jr. Natural history of systemic sclerosis and the assessment of disease activity, severity, functional status, and psychologic well-being. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2003;29:255–73.

-

27Valentini G, Silman AJ, Veale D. Assessment of disease activity. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21:S39–41.

-

28Rannou F, Poiraudeau S, Berezné A, Baubet T, Le-Guern V, Cabane J, et al. Assessing disability and quality of life in systemic sclerosis: construct validities of the Cochin hand function scale, health assessment questionnaire (HAQ), systemic sclerosis HAQ, and medical outcomes study 36-item short form health survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:94–102.

-

29Georges C, Chassany O, Mouthon L, Tiev K, Toledano C, Meyer O, et al. Validation of French version of the Scleroderma Health Assessment Questionnaire (SSc HAQ). Clin Rheumatol. 2005;24:3–10.

-

30Xinyi NG, Thumboo J, Low AHL. Validation of the scleroderma health assessment questionnaire and quality of life in English and Chinese-speaking patients with systemic sclerosis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15:268–76.

-

31Dellavance A, Gabriel A Jr, Cintra AFU, Ximenes AC, Nuccitelli B, Tabilerti BH, et al. II Consenso Brasileiro de Fator Antinuclear em células Hep-2. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2003;43:129–40.

-

32Codullo V, Morozzi G, Bardoni A, Salvini R, Deleonardi G, Pità O, et al. Validation of a new immunoenzymatic method to detect antibodies to RNA polymerase III in systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:373–7.

-

33Skare TL, Luciano AC, Fonseca AE, Azevedo PM. Autoanticorpos em esclerodermia e sua associação ao perfil clínico da doença. Estudo em 66 pacientes do sul do Brasil. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1075–81.

-

34Müller CS, Paiva ES, Azevedo VF, Radominski SC, Lima Filho JHC. Perfil de autoanticorpos e correlação clínica em um grupo de pacientes com esclerose sistêmica na região Sul do Brasil. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2011;51:319–24.

-

35Hunzelmann N, Genth E, Krieg T, Lehmacher W, Melchers I, Meurer M, et al. The registry of the German network for systemic scleroderma: frequency of disease subsets and patterns of organ involvement. Rheumatology. 2008;47:1185–92.

-

36Ferri C, Valentini G, Cozzi F, Sebastiani M, Michelassi C, La Montagna G, et al. Systemic sclerosis: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in 1012 Italian patients. Medicine. 2002;81:139–53.

-

37Sampaio-Barros PD, Bortoluzzo AB, Marangoni RG, Rocha LF, Del Rio APT, Samara AM, et al. Survival, causes of death, and prognostic factors in systemic sclerosis: analysis of 947 Brazilian patients. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:1971–8.

-

38Guidolim F, Esmanhotto L, Magro CE, Silva MB, Skare TL. Prevalência de achados cutâneos em portadores de esclerose sistêmica – Experiência de um hospital universitário. An Bras Dermatol. 2005;80:481–6.

-

39Hu PQ, Fertig N, Medsger T Jr, Wright TM. Correlation of serum anti-DNA topoisomerase I antibody levels with disease severity and activity in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1363–73.

-

40Hénault J, Robitaille G, Senécal JL, Raymond Y. DNA topoisomerase I binding to fibroblastos induces monocyte adhesion and activation in the presence of anti-topoisomerase I autoantibodies from systemic sclerosis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:963–73.

-

41Hu PQ, Hurwitz AA, Oppenheim JJ. Immunization with DNA topoisomerase I induces autoimune responses but not scleroderma-like pathologies in mice. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:2243–52.

-

42Nikpour M, Hissaria P, Byron J, Sahhar J, Micallef M, Paspaliaris W, et al. Prevalence, correlates and clinical usefulness of antibodies to RNA polymerase III in systemic sclerosis: a cross-sectional analysis of data from an Australian cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13. R211. (doi: http://arthritis-research.com/content/13/6/R211).

» http://arthritis-research.com/content/13/6/R211 -

43Vanthuyne M, Smith V, De Langhe E, Praet JV, Arat S, Depresseux G, et al. The Belgian systemic sclerosis cohort: correlations between disease severity sclores, cutaneous subsets, and autoantibody profile. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:2127–33.

-

44Rasco RG, Palma MJC, Hernández FJG, Román JS. Coexistencia de anticuerposanti-topoisomerase I y anticentrômero em la esclerodermia. Med Clín (Barc). 2010;135:430–1.

-

45Dick T, Mierau R, Bartz-Bazzanella P, Alavi M, Stoyanova-Scholz M, Kindler J, et al. Coexistence of anti-topoisomerase I and anticentromere antibodies in patients with systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:121–7.

-

46Morita Y, Muro Y, Sugiura K, Tomita Y, Tamakoshi K. Results of the Health Assessment Questionnaire for Japanese patients with systemic sclerosis – Measuring functional impairment in systemic sclerosis versus other connective tissue diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:367–72.

-

47Pope J. Measures of systemic sclerosis (Scleroderma). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(S11):S98–111.

-

48Iudici M, Cuomo G, Vettori S, Avellino M, Valentini G. Quality of life as measured by the short-form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire in patients with early systemic sclerosis and undifferentiated connective tissue disease. Health Qual Life Out. 2013;11:23 (doi: http://www.hqlo.com/content/11/1/23).

» http://www.hqlo.com/content/11/1/23 -

49Danieli E, Airò P, Bettoni L, Cinquini M, Antonioli CM, Cavazzana I, et al. Health-related quality of life measured by the Short Form 36 (SF-36) in systemic sclerosis: correlations with indexes of disease activity and severity, disability, and depressive symptoms. Clin Rheumatol. 2005;24:48–54.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

May-Jun 2015

History

-

Received

28 Mar 2014 -

Accepted

21 Sept 2014