RESUMEN

La instrumentación de la vía aérea del paciente crítico (tubo endotraqueal o cánula de traqueostomía) impide que ésta pueda cumplir con su función de calentar y humidificar el gas inhalado. Sumado a ello la administración de gases medicinales fríos y secos, y los altos flujos a los que se someten los pacientes en ventilación mecánica invasiva o no invasiva, generan una condición aún más desfavorable. Debido a esto es imperativo utilizar algún dispositivo para acondicionar los gases entregados incluso en tratamientos de corta duración con el fin de evitar los daños potenciales sobre la estructura y función del epitelio respiratorio. En el ámbito de terapia intensiva es habitual para esto el uso de intercambiadores de calor y humedad, como así también el uso de sistemas de humidificación activa. Para su correcta utilización es necesario poseer el conocimiento necesario sobre las especificaciones técnicas, ventajas y desventajas de cada uno de estos dispositivos ya que el acondicionamiento de los gases inspirados representa una intervención clave en pacientes con vía aérea artificial y se ha transformado en un cuidado estándar. La selección incorrecta del dispositivo o la configuración inapropiada pueden impactar negativamente en los resultados clínicos. Los integrantes del Capítulo de Kinesiología Intensivista de la Sociedad Argentina de Terapia Intensiva realizaron una revisión narrativa con el objetivo de exponer la evidencia disponible en relación al acondicionamiento del gas inhalado en pacientes con vía aérea artificial, profundizando sobre los conceptos relacionados a los principios de funcionamiento de cada uno.

Descriptores:

Sistemas de humidificación; Ventilación mecánica; Manejo de la vía aérea

ABSTRACT

Instrumentation of the airways in critical patients (endotracheal tube or tracheostomy cannula) prevents them from performing their function of humidify and heating the inhaled gas. In addition, the administration of cold and dry medical gases and the high flows that patients experience during invasive and non-invasive mechanical ventilation generate an even worse condition. For this reason, a device for gas conditioning is needed, even in short-term treatments, to avoid potential damage to the structure and function of the respiratory epithelium. In the field of intensive therapy, the use of heat and moisture exchangers is common for this purpose, as is the use of active humidification systems. Acquiring knowledge about technical specifications and the advantages and disadvantages of each device is needed for proper use since the conditioning of inspired gases is a key intervention in patients with artificial airway and has become routine care. Incorrect selection or inappropriate configuration of a device can have a negative impact on clinical outcomes. The members of the Capítulo de Kinesiología Intensivista of the Sociedad Argentina de Terapia Intensiva conducted a narrative review aiming to show the available evidence regarding conditioning of inhaled gas in patients with artificial airways, going into detail on concepts related to the working principles of each one.

Keywords:

Humidification systems; Mechanical ventilation; Airway management

INTRODUCCIÓN

El acondicionamiento de los gases medicinales administrados a los pacientes se ha convertido en un cuidado estándar de la salud. En condiciones normales, la vía aérea superior y el tracto respiratorio son responsables de que el aire inspirado gane temperatura y se cargue de humedad, proceso definido como acondicionamiento del gas inhalado.(11 Lindemann J, Leiacker R, Rettinger G, Keck T. Nasal mucosal temperature during respiration. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2002;27(3):135-9.,22 Keck T, Leiacker R, Riechelmann H, Rettinger G. Temperature profile in the nasal cavity. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(4):651-4.) Este proceso es clave para que el gas adquiera condiciones óptimas y se eviten daños potenciales sobre la estructura y función del epitelio respiratorio.(33 Walker AK, Bethune DW. A comparative study of condenser humidifiers. Anaesthesia. 1976;31(8):1086-93.

4 Mercke U. The influence of temperature on mucociliary activity. Temperature range 40 degrees C to 50 degrees C. Acta Otolaryngol. 1974;78(3-4):253-8.

5 Burton JD. Effects of dry anaesthetic gases on the respiratory mucous membrane. Lancet. 1962;1(7223):235-8.-66 Rathgeber J, Kazmaier S, Penack O, Züchner K. Evaluation of heated humidifiers for use on intubated patients: a comparative study of humidifying efficiency, flow resistance, and alarm functions using a lung model. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(6):731-9.)

La instrumentación de la vía aérea (tubo endotraqueal o cánula de traqueostomía) impide el acondicionamiento del gas inspirado, sumado a ello la administración de gases medicinales fríos y secos y los altos flujos a los que se someten los pacientes en ventilación mecánica invasiva (VMi) o no invasiva (VMNi), generan una condición aún más desfavorable.(77 Déry R. The evolution of heat and moisture in the respiratory tract during anaesthesia with a non-rebreathing system. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1973;20(3):296-309.) Debido a esto es imperativo utilizar algún dispositivo externo al paciente para acondicionar los gases entregados incluso en tratamientos de corta duración.

METODOS

Para confeccionar esta revisión narrativa el Capítulo de Kinesiología Intensivista de la Sociedad Argentina de Terapia Intensiva (SATI) realizó una búsqueda bibliográfica que se llevó a cabo en las bases de datos LILACS, MEDLINE, Biblioteca Cochrane y SciELO, con los siguientes términos y palabras combinadas: "randomized controlled trial" OR "controlled clinical trial" OR "trial" OR "groups" AND "humidifiers" AND "heat and moisture exchangers" OR "heat and moisture exchangers filters" AND "heated humidifiers" OR "heated humidified" AND "mechanical ventilation" AND "noninvasive ventilation" AND "spontaneous breathing". Los artículos más relevantes fueron seleccionados según el criterio de los autores.

Concepto de humedad

La humedad es la cantidad de agua en forma de vapor contenido en un gas y se caracteriza generalmente en términos de humedad absoluta o relativa.(88 Lucato JJ, Adams AB, Souza R, Torquato JA, Carvalho CR, Marini JJ. Evaluating humidity recovery efficiency of currently available heat and moisture exchangers: a respiratory system model study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64(6):585-90.

9 American Association for Respiratory Care, Restrepo RD, Walsh BK. Humidification during invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation: 2012. Respir Care. 2012;57(5):782-8.-1010 Branson RD, Campbell RS, Davis K, Porembka DT. Anaesthesia circuits, humidity output, and mucociliary structure and function. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1998;26(2):178-83.) La temperatura que el gas alcance es muy importante, ya que de ésta depende el contenido de vapor de agua del mismo. La humedad relativa representa el porcentaje (%) de vapor de agua que posee un gas en relación a su máxima capacidad de transporte. La humedad absoluta es la cantidad total de vapor de agua que contiene un gas y se expresa en miligramos de agua suspendidos en litros de gas (mg/L). La humedad absoluta tiene relación directa con la temperatura del gas y es importante en términos de humidificación, ya que, en un gas con baja temperatura, la humedad relativa puede ser del 100% y su humedad absoluta estar muy por debajo del valor recomendado(88 Lucato JJ, Adams AB, Souza R, Torquato JA, Carvalho CR, Marini JJ. Evaluating humidity recovery efficiency of currently available heat and moisture exchangers: a respiratory system model study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64(6):585-90.,99 American Association for Respiratory Care, Restrepo RD, Walsh BK. Humidification during invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation: 2012. Respir Care. 2012;57(5):782-8.) (Figura 1 y Tabla 1).

Fisiología de la vía aérea superior. Rol en el acondicionamiento de los gases

El acondicionamiento del aire inspirado es el proceso mediante el cual un gas es calentado y humidificado en su pasaje por la vía aérea para llegar en condiciones óptimas a nivel alveolar.(55 Burton JD. Effects of dry anaesthetic gases on the respiratory mucous membrane. Lancet. 1962;1(7223):235-8.)

Aunque el gas adquiere temperatura y humedad a lo largo del recorrido por la vía aérea, la principal zona donde se produce el calentamiento del aire inspirado es la nariz.(55 Burton JD. Effects of dry anaesthetic gases on the respiratory mucous membrane. Lancet. 1962;1(7223):235-8.,1111 Forbes AR. Temperature, humidity and mucus flow in the intubated trachea. Br J Anaesth. 1974;46(1):29-34.

12 Wiesmiller K, Keck T, Leiacker R, Lindemann J. Simultaneous in vivo measurements of intranasal air and mucosal temperature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264(6):615-9.-1313 Keck T, Leiacker R, Heinrich A, Kühnemann S, Rettinger G. Humidity and temperature profile in the nasal cavity. Rhinology. 2000;38(4):167-71.) La temperatura de la mucosa nasal se encuentra alrededor de los 32ºC, y aunque el tiempo de contacto entre el aire inspirado y la mucosa nasal es corto, es suficiente para transferirle calor. Por otro lado, la nariz tiene un gran potencial para regular la perfusión sanguínea y de esta manera contrabalancear la pérdida de calor en inspiración. Además, el aire circula por un conducto estrecho generando flujo turbulento que permite optimizar el calentado, humidificación y filtrado.(1212 Wiesmiller K, Keck T, Leiacker R, Lindemann J. Simultaneous in vivo measurements of intranasal air and mucosal temperature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264(6):615-9.,1313 Keck T, Leiacker R, Heinrich A, Kühnemann S, Rettinger G. Humidity and temperature profile in the nasal cavity. Rhinology. 2000;38(4):167-71.) Durante la espiración la humedad del aire exhalado es parcialmente conservada por condensación sobre la mucosa debido a la diferencia de temperatura. Alrededor del 25% del calor y humedad es recuperado durante la exhalación.(1111 Forbes AR. Temperature, humidity and mucus flow in the intubated trachea. Br J Anaesth. 1974;46(1):29-34.)

Como la temperatura del gas inspirado aumenta en su recorrido a través de la vía aérea, a nivel de la interfaz alveolo-capilar se encuentra a temperatura corporal (37ºC), con humedad relativa 100% y 44mg/L de humedad absoluta. En el punto donde el gas adquiere estas condiciones se conoce como límite de saturación isotérmica y normalmente se encuentra alrededor de la 4ta o 5ta generación bronquial. Alcanzar el límite de saturación isotérmica es fundamental para evitar daños sobre la mucosa y el epitelio ciliar.(77 Déry R. The evolution of heat and moisture in the respiratory tract during anaesthesia with a non-rebreathing system. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1973;20(3):296-309.)

La presencia de una vía aérea artificial impide que el aire inspirado entre en contacto con la mucosa de la vía aérea superior afectando su acondicionamiento (Figura 2). Además, si se administran gases medicinales existe riesgo de generar alteraciones del clearence y de la mucosa(55 Burton JD. Effects of dry anaesthetic gases on the respiratory mucous membrane. Lancet. 1962;1(7223):235-8.,88 Lucato JJ, Adams AB, Souza R, Torquato JA, Carvalho CR, Marini JJ. Evaluating humidity recovery efficiency of currently available heat and moisture exchangers: a respiratory system model study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64(6):585-90.) ya que estos son fríos y secos.(1414 Pillow JJ, Hillman NH, Polglase GR, Moss TJ, Kallapur SG, Cheah FC, et al. Oxygen, temperature and humidity of inspired gases and their influences on airway and lung tissue in near-term lambs. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(12):2157-63.)

Existen dos tipos de dispositivos para acondicionar los gases inspirados: los intercambiadores de calor y humedad (HME - heat and moisture exchanger) y los humidificadores activos.(1515 Uchiyama A, Yoshida T, Yamanaka H, Fujino Y. Estimation of tracheal pressure and imposed expiratory work of breathing by the endotracheal tube, heat and moisture exchanger, and ventilator during mechanical ventilation. Respir Care. 2013;58(7):1157-69.)

Sea cual fuere el dispositivo de elección el mismo debe indefectiblemente alcanzar los requerimientos mínimos para suplir la función de la vía aérea superior, que según la American Association for Respiratory Care son:(99 American Association for Respiratory Care, Restrepo RD, Walsh BK. Humidification during invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation: 2012. Respir Care. 2012;57(5):782-8.)

-

- 30mg/L de humedad absoluta, 34°C de temperatura y 100% de humedad relativa para los HME.

-

- Entre 33 y 44mg/L de humedad absoluta; entre 34°C y 41°C de temperatura; 100% humedad relativa para los humidificadores activos.

HUMIDIFICADORES PASIVOS

Clasificación

El principio básico de funcionamiento de todos estos dispositivos radica en su capacidad para retener el calor y humedad durante la espiración y entregar al menos el 70% de éstos al gas inhalado durante la inspiración posterior. Esta función "pasiva" se puede conseguir mediante diferentes mecanismos y en base a los cuales radica su clasificación.(1616 Eckerbom B, Lindholm CE. Performance evaluation of six heat and moisture exchangers according to the Draft International Standard (ISO/DIS 9360). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34(5):404-9.

17 Cohen IL, Weinberg PF, Fein IA, Rowinski GS. Endotracheal tube occlusion associated with the use of heat and moisture exchangers in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1988;16(3):277-9.

18 Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.

19 Martin C, Papazian L, Perrin G, Saux P, Gouin F. Preservation of humidity and heat of respiratory gases in patients with a minute ventilation greater than 10 L/min. Crit Care Med. 1994;22(11):1871-6.

20 Martin C, Thomachot L, Quinio B, Viviand X, Albanese J. Comparing two heat and moisture exchangers with one vaporizing humidifier in patients with minute ventilation greater than 10 L/min. Chest. 1995;107(5):1411-5.

21 Unal N, Kanhai JK, Buijk SL, Pompe JC, Holland WP, Gültuna I, et al. A novel method of evaluation of three heat-moisture exchangers in six different ventilator settings. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24(2):138-46.-2222 Wilkes AR. Heat and moisture exchangers. Structure and function. Respir Care Clin N Am. 1998;4(2):261-79.)

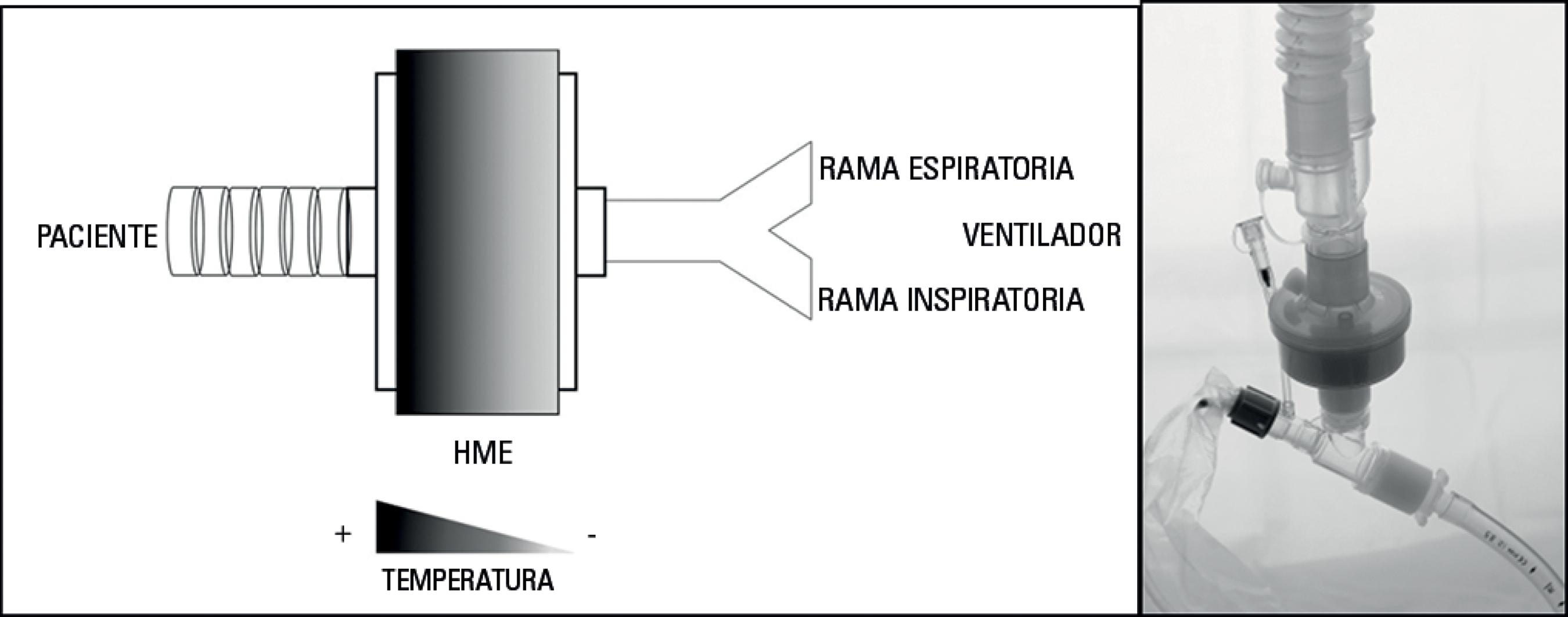

a. Intercambiador de calor y humedad

Actualmente los HMEs son condensadores simples confeccionados con elementos de espuma desechable, fibra sintética o papel, con un área de superficie considerable que logra generar un gradiente de temperatura efectivo a través del dispositivo entregando calor en cada inspiración. Derivados del campo de la filtración, se crearon HMEs hidrofóbicos para repeler la humedad y retener el calor del gas espirado entregándolo en la siguiente inspiración (Figura 3).(88 Lucato JJ, Adams AB, Souza R, Torquato JA, Carvalho CR, Marini JJ. Evaluating humidity recovery efficiency of currently available heat and moisture exchangers: a respiratory system model study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64(6):585-90.,1616 Eckerbom B, Lindholm CE. Performance evaluation of six heat and moisture exchangers according to the Draft International Standard (ISO/DIS 9360). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34(5):404-9.,2323 Lee MG, Ford JL, Hunt PB, Ireland DS, Swanson PW. Bacterial retention properties of heat and moisture exchange filters. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69(5):522-5.,2424 Boyer A, Thiéry G, Lasry S, Pigné E, Salah A, de Lassence A, et al. Long-term mechanical ventilation with hygroscopic heat and moisture exchangers used for 48 hours: a prospective clinical, hygrometric, and bacteriologic study. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(3):823-9.)

Descripción esquemática del principio de funcionamiento de un intercambiador de calor y humedad y sitio de colocación en el circuito del ventilador.

b. Condensador humidificador higroscópico (HCH - hygroscopic condenser humidifier) o intercambiador de calor y humedad higroscópico (HHME - hygroscopic heat and moisture exchanger)

A diferencia de los HME, los HCH o HHME son dispositivos elaborados con fibra sintética recubiertos por un producto químico higroscópico (cloruro de calcio o litio) mediante el cual absorbe el vapor de agua espirado y lo entrega al gas inspirado, optimizando la entrega de humedad. La fibra sintética ayuda además a reducir la acumulación de condensación en la posición dependiente del dispositivo.(88 Lucato JJ, Adams AB, Souza R, Torquato JA, Carvalho CR, Marini JJ. Evaluating humidity recovery efficiency of currently available heat and moisture exchangers: a respiratory system model study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64(6):585-90.,1717 Cohen IL, Weinberg PF, Fein IA, Rowinski GS. Endotracheal tube occlusion associated with the use of heat and moisture exchangers in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1988;16(3):277-9.,1818 Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.)

c. Intercambiadores de calor y humedad con filtro

Estos dispositivos están construidos con los materiales necesarios para humidificar y calentar según su principio de funcionamiento (hidrofóbico o higroscópico) y además contienen un filtro electrostático. Los filtros son una capa plana de material de fibra (modacrílicas o de polipropileno) que actúa como barrera al flujo de gas; a su vez se optimiza el rendimiento de filtración aplicando un material con carga electrostática.(2525 Turnbull D, Fisher PC, Mills GH, Morgan-Hughes NJ. Performance of breathing filters under wet conditions: a laboratory evaluation. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94(5):675-82.)

Dentro de estos existen: intercambiador de calor humedad con filtro (HMEF - heat and moisture exchanger filter), condensador humidificador higroscópico con filtro (HCHF - hygroscopic condenser humidifier filter o HHMEF - hygroscopic heat and moisture exchanger filter).(1818 Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.)

d. Intercambiadores de calor y humedad combinados

Los elementos higroscópicos e hidrofóbicos se utilizan conjuntamente para crear un HME combinado. El rendimiento en términos de humedad absoluta es mejor en los HCHs que en los HMEs, pero similar entre los HCHs y los HME combinados.(2424 Boyer A, Thiéry G, Lasry S, Pigné E, Salah A, de Lassence A, et al. Long-term mechanical ventilation with hygroscopic heat and moisture exchangers used for 48 hours: a prospective clinical, hygrometric, and bacteriologic study. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(3):823-9.,2626 Davis K Jr, Evans SL, Campbell RS, Johannigman JA, Luchette FA, Porembka DT, et al. Prolonged use of heat and moisture exchangers does not affect device efficiency or frequency rate of nosocomial pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(5):1412-8.)

HUMIDIFICADORES PASIVOS - CONSIDERACIONES ESPECIALES

Espacio muerto

El principio de funcionamiento de los humidificadores pasivos implica que a mayor volumen del material condensador mejor será la performance del dispositivo (Figura 4). Por esto el espacio muerto "ideal" de un humidificador pasivo es de alrededor de 50mL.(1818 Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.)

A) intercambiador de calor y humedad para pacientes con vía aérea artificial en ventilación espontánea (especialmente para pacientes traqueostomizados). B) comparación gráfica entre los volúmenes de un intercambiador de calor y humedad convencional para uso en pacientes con vía aérea artificial en ventilación mecánica y uno para traqueostomizados en ventilación espontánea.

Esto no representa un inconveniente en los pacientes con VMi, debido a que el espacio muerto puede ser compensado con la programación de ventilador. Sin embargo, en pacientes con vía aérea artificial, sin requerimiento de VMi, el aumento del volumen minuto ventilatorio como mecanismo compensatorio del espacio muerto podría generar una carga difícil de tolerar en pacientes con baja reserva ventilatoria, por esto se desarrollaron humidificadores pasivos de "pequeño volumen" (Figura 4). Si bien pueden ser más "tolerables", tienen una baja capacidad de humidificación que empeora ante el aumento del volumen corriente (VC) y con O2 suplementario.(2727 Le Bourdellès G, Mier L, Fiquet B, Djedaïni K, Saumon G, Coste F, et al. Comparison of the effects of heat and moisture exchangers and heated humidifiers on ventilation and gas exchange during weaning trials from mechanical ventilation. Chest. 1996;110(5):1294-8.

28 Campbell RS, Davis K Jr, Johannigman JA, Branson RD. The effects of passive humidifier dead space on respiratory variables in paralyzed and spontaneously breathing patients. Respir Care. 2000;45(3):306-12.

29 Chikata Y, Oto J, Onodera M, Nishimura M. Humidification performance of humidifying devices for tracheostomized patients with spontaneous breathing: a bench study. Respir Care. 2013;58(9):1442-8.-3030 Brusasco C, Corradi F, Vargas M, Bona M, Bruno F, Marsili M, et al. In vitro evaluation of heat and moisture exchangers designed for spontaneously breathing tracheostomized patients. Respir Care. 2013;58(11):1878-85.)

Considerar el espacio muerto instrumental adicionado por los humidificadores pasivos durante la VMi, se torna relevante cuando la patología obliga a estrategias de protección pulmonar (bajo VC). Los estudios de Prat(3131 Prat G, Renault A, Tonnelier JM, Goetghebeur D, Oger E, Boles JM, et al. Influence of the humidification device during acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(12):2211-5.) y Hinkson(3232 Hinkson CR, Benson MS, Stephens LM, Deem S. The effects of apparatus dead space on P(aCO2) in patients receiving lung-protective ventilation. Respir Care. 2006;51(10):1140-4.) dan cuenta de esto, evidenciando cambios considerables en la presión arterial de dióxido de carbono (PaCO2) (y en el pH) ante estas circunstancias.

Resistencia

Si bien la resistencia en un dispositivo sin uso podría considerarse despreciable (5cmH2O/L/seg evaluado "seco": International Standards Organization Draft International Standard 9360-2)(3333 International Standardization Organization (ISO). Anaesthetic and respiratory equipment - Heat and moisture exchangers (HMEs) for humidifying respired gases in humans - Part 2: HMEs for use with tracheostomized patients having minimum tidal volumes of 250 ml. EN ISO 9360-2:2009, ISO 9360-2:2001. Available from: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:9360:-2:ed-1:v1:en.

https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:...

) puede variar ante cambios en las condiciones (presencia de condensación, impactación por secreciones, cambios de parámetros ventilatorios, aumento del VC y del flujo). Aunque algunos estudios(1818 Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.,3434 Lucato JJ, Tucci MR, Schettino GP, Adams AB, Fu C, Forti G Jr, et al. Evaluation of resistance in 8 different heat-and-moisture exchangers: effects of saturation and flow rate/profile. Respir Care. 2005;50(5):636-43.,3535 Chiaranda M, Verona L, Pinamonti O, Dominioni L, Minoja G, Conti G. Use of heat and moisture exchanging (HME) filters in mechanically ventilated ICU patients: influence on airway flow-resistance. Intensive Care Med.1993;19(8):462-6.) han demostrado que la presencia de "humedad" en el dispositivo no genera cambios considerables en la resistencia, aunque hay que considerar que la condensación excesiva o la impactación (por secreciones o sangre), puede alterarla.

HUMIDIFICADORES PASIVOS

Implementación y monitoreo

Por su principio de funcionamiento debe estar siempre colocado por delante de la pieza en "Y" del circuito, lo que permite que el dispositivo tome contacto con el aire espirado e inspirado en cada ciclo ventilatorio (Figura 3), esto hace que el humidificador pasivo forme parte del espacio muerto instrumental.(1919 Martin C, Papazian L, Perrin G, Saux P, Gouin F. Preservation of humidity and heat of respiratory gases in patients with a minute ventilation greater than 10 L/min. Crit Care Med. 1994;22(11):1871-6.)

Volumen del intercambiador de calor y humedad y su relación con la capacidad de humidificación

Si bien hay varios factores que afectan la entrega de humedad al paciente, el volumen interno y la humedad absoluta aportada son 2 variables importantes a considerar.

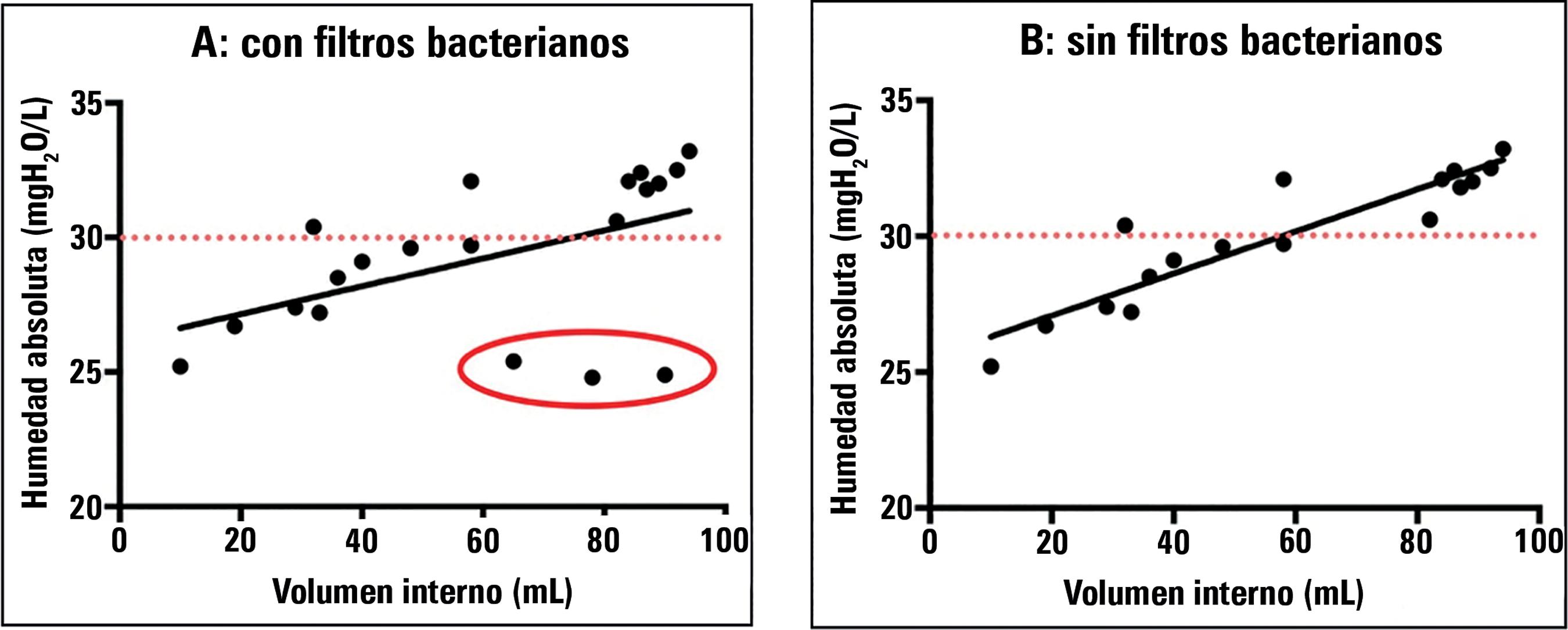

En un estudio de banco, Eckerbom et al.(1616 Eckerbom B, Lindholm CE. Performance evaluation of six heat and moisture exchangers according to the Draft International Standard (ISO/DIS 9360). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34(5):404-9.) relacionaron el espacio muerto del HME con la humedad absoluta aportada, reportando una pobre correlación entre ambas variables. Sin embargo, solo se evaluaron 6 dispositivos, algunos de los cuales eran filtros bacterianos, por lo que los resultados deberían tomarse con mucha cautela. Con el fin de analizar con mayor profundidad los resultados aportados por este estudio, realizamos un gráfico de dispersión (Figura 5) con las variables mencionadas, en donde se evidencia una pobre correlación entre éstas (r = 0,36; p = 0,47).

Correlación entre volumen interno y la humedad entregada en el estudio de Eckerbom. La programación del ventilador corresponde al "Setting II" del estudio (volumen corriente de 500mL, frecuencia respiratoria de 20 respiraciones por minuto). Para el análisis estadístico se utilizó el coeficiente de correlación de Pearson.

Más tarde Branson et al.(1818 Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.) trataron de replicar el estudio anteriormente mencionado, con las mismas normas ISO pero con mayor cantidad de dispositivos. En los resultados mencionan que a medida que aumenta el espacio muerto, lo hace la humedad absoluta aportada. En un intento por ahondar en los resultados, realizamos los siguientes gráficos de correlación utilizando los datos aportados por el estudio de Branson(1818 Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.) (Figura 6). En la figura 6A se puede observar una pobre correlación (r = 0,5; p = 0,01) entre ambas variables. Sin embargo, analizando detalladamente los dispositivos utilizados, observamos que se habían incluido 3 filtros bacterianos (marcados con círculo rojo). Al repetir el análisis, excluyendo los resultados relacionados a esos tres dispositivos, encontramos una correlación excelente (Figura 6B; r = 0,91; p < 0,0001).

Correlación entre el volumen interno del intercambiador de calor y humedad y la humedad absoluta entregada. La programación del ventilador corresponde al "Setting I" (volumen corriente de 500mL, frecuencia respiratoria de 20 respiraciones por minuto). En el "B" se realizó el mismo análisis que en el "A" excluyendo los 3 filtros bacterianos (Pall, Intertech HEPA, Intersurgical). El estadístico utilizado fue el coeficiente de correlación de Pearson.

La relación entre la humedad absoluta aportada y el espacio muerto en mL es una medida de eficacia descripta en la literatura,(1818 Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.) siendo más efectivos los que posean mayor valor, es decir mayor entrega de humedad absoluta por unidad de volumen interno. Los humidificadores que alcanzaban el límite recomendado de 30mg/L9, tenían un espacio muerto aproximado de 60mL (Figura 6A y B).

Considerando esto, podemos asumir que el volumen del dispositivo tiene influencia sobre el rendimiento y que es una variable a considerar durante la elección de los HMEs.

Volumen minuto y performance de los intercambiadores de calor y humedad

La performance de humidificación de los HME disminuye con el aumento del volumen minuto.(88 Lucato JJ, Adams AB, Souza R, Torquato JA, Carvalho CR, Marini JJ. Evaluating humidity recovery efficiency of currently available heat and moisture exchangers: a respiratory system model study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64(6):585-90.,1616 Eckerbom B, Lindholm CE. Performance evaluation of six heat and moisture exchangers according to the Draft International Standard (ISO/DIS 9360). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34(5):404-9.,1818 Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.

19 Martin C, Papazian L, Perrin G, Saux P, Gouin F. Preservation of humidity and heat of respiratory gases in patients with a minute ventilation greater than 10 L/min. Crit Care Med. 1994;22(11):1871-6.

20 Martin C, Thomachot L, Quinio B, Viviand X, Albanese J. Comparing two heat and moisture exchangers with one vaporizing humidifier in patients with minute ventilation greater than 10 L/min. Chest. 1995;107(5):1411-5.-2121 Unal N, Kanhai JK, Buijk SL, Pompe JC, Holland WP, Gültuna I, et al. A novel method of evaluation of three heat-moisture exchangers in six different ventilator settings. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24(2):138-46.) Algunos trabajos encontraron menor humedad absoluta aportada con el aumento del VC(88 Lucato JJ, Adams AB, Souza R, Torquato JA, Carvalho CR, Marini JJ. Evaluating humidity recovery efficiency of currently available heat and moisture exchangers: a respiratory system model study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64(6):585-90.,1616 Eckerbom B, Lindholm CE. Performance evaluation of six heat and moisture exchangers according to the Draft International Standard (ISO/DIS 9360). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34(5):404-9.) mientras que sólo Unal et al.(2121 Unal N, Kanhai JK, Buijk SL, Pompe JC, Holland WP, Gültuna I, et al. A novel method of evaluation of three heat-moisture exchangers in six different ventilator settings. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24(2):138-46.) encontraron que el flujo era una variable que afectaba el rendimiento. Puede que las diferencias encontradas en los estudios se deban a los diferentes modelos de laboratorio utilizados (métodos higrométricos o métodos gravimétricos). Sin embargo, en 2014, Lellouche et al.(3636 Lellouche F, Qader S, Taillé S, Lyazidi A, Brochard L. Influence of ambient temperature and minute ventilation on passive and active heat and moisture exchangers. Respir Care. 2014;59(5):637-43.) estudiaron el impacto de la ventilación minuto (10 versus 20L/minuto) y la temperatura ambiente sobre los HMEs de última generación reportando efectos insignificantes sobre el rendimiento de dichos dispositivos [humedad absoluta aportada con un volumen minuto > 10L/minuto fue de 30,9mg/L]. Por este motivo dicho autores recomiendan que la ventilación minuto no se tenga en cuenta como una limitación de los humidificadores de última generación. De todas maneras, como el volumen minuto está compuesto por la frecuencia respiratoria y el VC, tal vez valga la pena investigar más a fondo el tema. El aumento del VC en el estudio en cuestión era modesto, un aumento de 150mL (500 a 650mL que equivale al 30%), mientras que el aumento de la frecuencia respiratoria fue mayor, de 20 a 30 resp/minuto (50%). La pregunta sería: ¿cuál de los 2 componentes del volumen minuto (VC o frecuencia respiratoria), es el que posee mayor efecto sobre el rendimiento de un humidificador?

Dos estudios compararon(1616 Eckerbom B, Lindholm CE. Performance evaluation of six heat and moisture exchangers according to the Draft International Standard (ISO/DIS 9360). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34(5):404-9.,1818 Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.) el rendimiento en términos de humidificación de los HMEs utilizando métodos y condiciones de prueba basados en la norma ISO 9360:1992. En ambos estudios, se produjo un efecto más marcado en el rendimiento al cambiar el VC de 500mL a 1000mL (aumento del 100%) en comparación con el cambio de la frecuencia respiratoria de 10 a 20 resp/minuto (aumento de 100%), lo que sugiere que VC tiene el efecto primario.(1616 Eckerbom B, Lindholm CE. Performance evaluation of six heat and moisture exchangers according to the Draft International Standard (ISO/DIS 9360). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34(5):404-9.,1818 Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.) Sin embargo por lo inusual de utilizar VC de 1000mL los resultados deberían tomarse con cautela.

Tiempo de contacto con el aire

Eckerbom et al.(1616 Eckerbom B, Lindholm CE. Performance evaluation of six heat and moisture exchangers according to the Draft International Standard (ISO/DIS 9360). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34(5):404-9.) al evaluar el tiempo de contacto del gas inspirado no observaron diferencias significativas entre 1 versus 2 segundos en la humedad absoluta aportada. Branson et al.(1818 Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.) mencionan que el flujo espiratorio podría ser una variable a considerar, ya que a mayor flujo espiratorio, menor tiempo de contacto entre el gas y el HME y por ende menor humedad absoluta aportada.

HUMIDIFICADORES PASIVOS - CAMBIO

Si bien existen recomendaciones generales realizadas por los fabricantes para el cambio de estos dispositivos, podríamos considerar como recomendación "ideal" que el cambio sea:

-

- Por condensación excesiva que aumente la resistencia.

-

- Por impactación visible con secreciones o sangre.

-

- Cada 48 horas en pacientes con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica.

-

- Cada 96 horas y hasta 1 semana en el resto de los pacientes.(3737 Thomachot L, Boisson C, Arnaud S, Michelet P, Cambon S, Martin C. Changing heat and moisture exchangers after 96 hours rather than after 24 hours: a clinical and microbiological evaluation. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(3):714-20.

38 Ricard JD, Le Mière E, Markowicz P, Lasry S, Saumon G, Djedaïni K, et al. Efficiency and safety of mechanical ventilation with a heat and moisture exchanger changed only once a week. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(1):104-9.-3939 Thomachot L, Leone M, Razzouk K, Antonini F, Vialet R, Martin C. Randomized clinical trial of extended use of a hydrophobic condenser humidifier: 1 vs. 7 days. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1):232-7.)

HUMIDIFICADORES ACTIVOS

Los humidificadores activos son dispositivos compuestos por un calentador eléctrico sobre el cual se coloca una carcasa plástica con base metálica en donde se deposita el agua estéril. Al calentarse la base, el agua gana temperatura por convección. Algunos, se caracterizan por ser autorregulados por un mecanismo que consiste en un cable de calefacción (circuito con alambre caliente) que mantiene la temperatura del gas constante a lo largo de su recorrido por el circuito y un cable con dos sensores de temperatura, que se conectan a la salida del calentador (distal) y en una pieza del circuito (próxima al paciente) para controlar la temperatura del sistema.

Hay que tener en cuenta que si bien los circuitos con alambre caliente mantienen estable la temperatura a lo largo de su recorrido y disminuyen la condensación, el déficit en su control expone al paciente a riesgos tales como mayor incidencia de oclusión de la vía aérea artificial.(4040 Roustan JP, Kienlen J, Aubas P, Aubas S, du Cailar J. Comparison of hydrophobic heat and moisture exchangers with heated humidifier during prolonged mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 1992;18(2):97-100.)

TIPOS DE HUMIDIFICADORES ACTIVOS

Humidificadores de burbuja

El flujo de aire que ingresa es forzado a pasar a través de un tubo que lo conduce a la parte inferior de la carcasa. El gas que sale del extremo distal del tubo (bajo la superficie del agua) forma burbujas, que ganan humedad y temperatura a medida que suben a la superficie del agua. Algunos factores que influyen en el contenido de humedad del gas son la cantidad de agua en el recipiente y la velocidad de flujo. Simplemente, si la columna de agua en el recipiente es más alta, la interfaz gas-agua también lo será. Inversamente, a mayor flujo circulante, menor será la performance del dispositivo. Estos dispositivos hoy en día se encuentran en desuso.(4141 Oh TE, Lin ES, Bhatt S. Resistance of humidifiers, and inspiratory work imposed by a ventilator-humidifier circuit. Br J Anaesth. 1991;66(2):258-63.)

Humidificadores pass-over

El flujo de aire pasa sobre la superficie del agua que está caliente y a través de la interfaz gas-agua que se genera, el gas circulante gana calor y humedad.(4141 Oh TE, Lin ES, Bhatt S. Resistance of humidifiers, and inspiratory work imposed by a ventilator-humidifier circuit. Br J Anaesth. 1991;66(2):258-63.) En comparación con el anterior este dispositivo disminuye la resistencia. Es importante considerar que la temperatura del agua de la carcasa será un factor determinante en términos de humedad.(4242 Roux NG, Plotnikow GA, Villalba DS, Gogniat E, Feld V, RiberoVairo N, et al. Evaluation of an active humidification system for inspired gas. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;8(1):69-75.,4343 Roux NG, Feld V, Gogniat E, Villalba D, Plotnikow G, Ribero Vairo N, et al. El frasco humidificador como sistema de humidificación del gas inspirado no cumple con las recomendaciones. Evaluación y comparación de tres sistemas de humidificación. Estudio de laboratorio. Med Intensiva. 2010;27(3).)

Una variante del humidificador pass-over es el humidificador tipo "wick", en el cual una membrana porosa que absorbe humedad (tipo papel secante) es introducida bajo el agua rodeada del elemento calentador, manteniendo constantemente dicha membrana saturada de vapor de agua. El gas seco entra a la cámara, toma contacto con el wick, y se carga de mayor vapor de agua que el sistema simple debido a que la interfaz líquido-gas es mayor.

Otra variante es el humidificador de membrana hidrofóbico, donde el gas seco pasa a través de la membrana y debido a las características de la misma, solo deja pasar vapor de agua. El gas seco se carga de vapor de agua y sale de la cámara.

HUMIDIFICADORES ACTIVOS - IMPLEMENTACIÓN Y MONITOREO

Armado

Los humidificadores activos van colocados en línea en la rama inspiratoria del respirador. El circuito que sale de la válvula inspiratoria se conecta al orificio de entrada de la carcasa plástica que deberá estar siempre llena hasta el nivel especificado por el fabricante. Posteriormente un segundo tramo de circuito (de largo estándar) se conecta al orificio de salida de la carcasa y a la "Y" del circuito, encargado de conducir los gases al paciente.

Con este tipo de dispositivos de humidificación es imprescindible la utilización de trampas de agua, reservorios con sistema de circulación unidireccional que permiten el depósito de la condensación excedente sin fuga de aire. La acumulación excesiva de agua en el circuito puede generar, entre otras cosas autodisparos, malinterpretación del monitoreo ventilatorio o incluso volcado de material contaminado hacia la vía aérea del paciente.

Cuidados y monitoreo

-

- Observar que la tubuladura drene el agua hacia abajo y no hacia la vía aérea artificial o el ventilador.

-

- Posicionar correctamente las trampas de agua para que reciban el agua drenada.

-

- Controlar frecuentemente el dispositivo (nivel de agua, nivel de temperatura, chequear la presencia de condensación).

-

- Nunca llenar por encima del nivel recomendado.

-

- No volcar la condensación hacia la cámara humidificadora.

-

- Cumplir con las especificaciones de fábrica.

HUMIDIFICADORES ESPECIALES

Humidificador para aerosolterapia

El HME para aerosolterapia Gibeck Humid-Flo® es un HME que tiene la característica de permanecer en línea durante la aplicación de aerosoles en ventilación mecánica, evitando la apertura del circuito y reduciendo potencialmente la contaminación de las tubuladuras así como la exposición del personal de salud a los gases contaminados.

Tiene 2 modalidades: "HME y AEROSOL", las cuales pueden seleccionarse rotando el eje central del dispositivo. Seleccionando HME, el dispositivo funciona como un humidificador pasivo convencional. En AEROSOL, la parte del humidificador es "salteado", por lo que el aerosol va directamente hacia el paciente y no impacta en el material humidificador. Sin embargo, la humedad absoluta entregada con este dispositivo es al menos cuestionable, ya que entrega 30,4mg/L, pero con un VC de 1000mL.

Recientemente Ari et al.(4444 Ari A, Alwadeai KS, Fink JB. Effects of heat and moisture exchangers and exhaled humidity on aerosol deposition in a simulated ventilator-dependent adult lung model. Respir Care. 2017;62(5):538-43.) evaluaron, en un estudio de banco, la performance de varios HME para ser utilizados en conjunto con aerosolterapia. Los autores no encontraron diferencias significativas en el depósito de la droga (albuterol) en el pulmón artificial sin HME (control) y con HME, utilizando un circuito húmedo (simulando la exhalación de gases real de un paciente). Si bien es solo un estudio de laboratorio, los HME modificados para aerosolterapia parecerían no interferir con la deposición de la droga.

Intercambiador de calor y humedad Booster

El HME-Booster® es un tipo de humidificación activa híbrida que consta de un sistema pasivo de humidificación y un conector en forma de "T" que contiene un calentador autocontrolado y una cámara de pequeño volumen para la infusión continua de agua destilada (consume 250mL cada 3 días aproximadamente). En la parte superior del dispositivo se encuentra una membrana hidrofóbica que solo permite el paso del agua cuando se evapora hacia la tubuladura. Por lo tanto durante la inspiración se agrega la humedad proveniente del agua que se evaporó sobre la membrana mejorando las condiciones del gas, aproximadamente entre 3 - 4mg/L (dependiendo del VC, relación I:E y tipo de HME utilizado).(4545 Thomachot L, Viviand X, Boyadjiev I, Vialet R, Martin C. The combination of a heat and moisture exchanger and a Booster: a clinical and bacteriological evaluation over 96 h. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(2):147-53.) Durante la fase espiratoria, el calor y la humedad son retenidos por las propiedades pasivas del sistema de humidificación. El espacio muerto del dispositivo es aproximadamente 9mL.

Ventajas: fácil de manejar, elimina la condensación excesiva en la tubuladura, podría ser de utilidad en pacientes hipotérmicos y tiene filtro bacteriano (los humidificadores activos no tienen).

Desventajas: no tiene monitoreo de la temperatura, aumenta la resistencia, requiere de una fuente de energía eléctrica (potencial riesgo de quemaduras y/o descargas eléctricas).(4646 Pelosi P, Severgnini P, Selmo G, Corradini M, Chiaranda M, Novario R, et al. In vitro evaluation of an active heat-and-moisture exchanger: the Hygrovent Gold. Respir Care. 2010;55(4):460-6.)

Intercambiadores de calor y humedad higroscópicos activos

Este dispositivo se compone de un HHME en una carcasa calentada en forma de cono con un corrugado y un controlador electrónico. Posee una línea entre el dispositivo y la fuente de agua, otra entre el corrugado y el controlador y una tercera de calentado del dispositivo entre éste y el controlador. La carcasa contiene un elemento de papel que proporciona una superficie de transferencia de humead del gas. Una fuente de agua gotea continuamente sobre el elemento de papel y el calor de la carcasa hace que el líquido se evapore aumentando la humedad del gas inhalado. Es controlado de manera electrónica con una unidad de control de agua y temperatura en base a la programación del volumen minuto del paciente.(4747 Branson RD, Campbell RS, Johannigman JA, Ottaway M, Davis K Jr, Luchette FA, et al. Comparison of conventional heated humidification with a new active hygroscopic heat and moisture exchanger in mechanically ventilated patients. Respir Care. 1999;44(8):912-7.)

Algunas de las ventajas propuestas son eliminar el condensado en la rama inspiratoria y evitar el uso de trampa de agua. Además, si la fuente de agua se agota, este dispositivo sigue funcionando como un HHME (aportando aproximadamente de 28 a 31mg/L de humedad absoluta). EL HHME activo proporciona temperaturas de 36 - 38°C y 90 - 95% de humedad relativa. La humedad absoluta aportada del dispositivo es similar que los HME o humidificadores activos pero con menos consumo de agua y menor condensación. El espacio muerto del dispositivo es de 73mL y la resistencia es de 1,7cmH2O/L/s.(4747 Branson RD, Campbell RS, Johannigman JA, Ottaway M, Davis K Jr, Luchette FA, et al. Comparison of conventional heated humidification with a new active hygroscopic heat and moisture exchanger in mechanically ventilated patients. Respir Care. 1999;44(8):912-7.)

Los inconvenientes de este producto son la posibilidad de quemaduras en la piel y el aumento de espacio muerto en comparación con un humidificador calentado o HHME solo.

HUMIDIFICADORES PASIVOS Y ACTIVOS

Ventajas y desventajas

Teniendo en cuenta la capacidad de humidificación, ventajas y desventajas, tanto los humidificadores pasivos como los activos son adecuados para acondicionar el gas inhalado (Tabla 2).(4848 Siempos II, Vardakas KZ, Kopterides P, Falagas ME. Impact of passive humidification on clinical outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(12):2843-51.,4949 Kelly M, Gillies D, Todd DA, Lockwood C. Heated humidification versus heat and moisture exchangers for ventilated adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(4):CD004711.) Si bien existen algunos datos a favor del uso de HMEF (or HCHF) por sobre los humidificadores activos para la prevención de neumonía asociada a la ventilación mecánica, la elección del dispositivo no debe basarse solo en términos de control de infecciones.(99 American Association for Respiratory Care, Restrepo RD, Walsh BK. Humidification during invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation: 2012. Respir Care. 2012;57(5):782-8.) En la figura 7 se propone un algoritmo para la selección del dispositivo de humidificación.

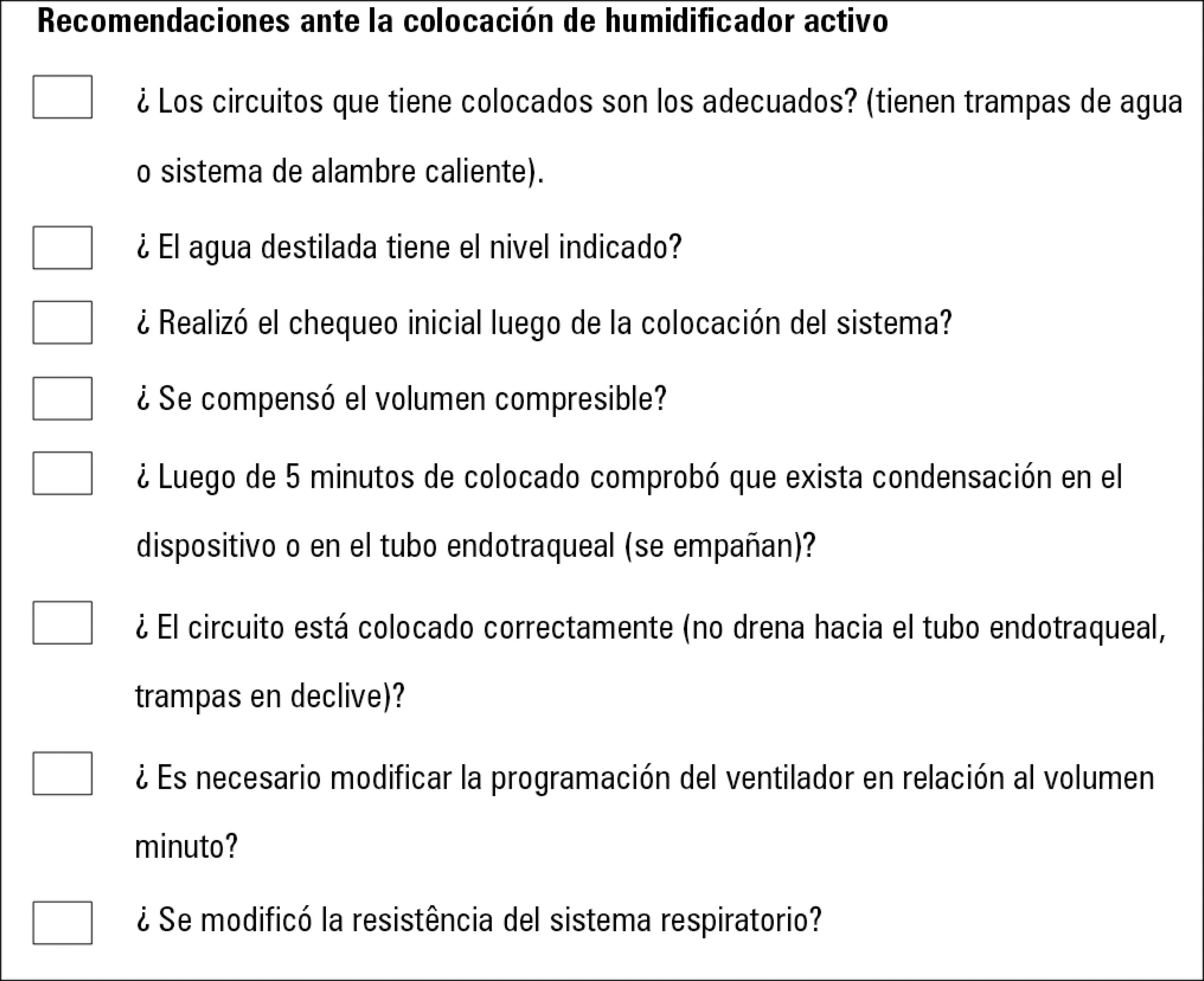

Con el fin de simplificar el chequeo que debe realizar al optar por un sistema de humidificación, generamos esta breve lista orientativa en donde figuran los principales puntos a tener en cuenta (Figuras 8 y 9).

Recomendaciones a tener en cuenta ante la colocación de un intercambiador de calor y humedad.

A la hora de decidir qué sistema de humidificación utilizar hay que tener presente los diferentes escenarios clínicos ya que cada dispositivo presenta características particulares que pueden impactar en la situación clínica del paciente (Tabla 3).(99 American Association for Respiratory Care, Restrepo RD, Walsh BK. Humidification during invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation: 2012. Respir Care. 2012;57(5):782-8.,2727 Le Bourdellès G, Mier L, Fiquet B, Djedaïni K, Saumon G, Coste F, et al. Comparison of the effects of heat and moisture exchangers and heated humidifiers on ventilation and gas exchange during weaning trials from mechanical ventilation. Chest. 1996;110(5):1294-8.

28 Campbell RS, Davis K Jr, Johannigman JA, Branson RD. The effects of passive humidifier dead space on respiratory variables in paralyzed and spontaneously breathing patients. Respir Care. 2000;45(3):306-12.-2929 Chikata Y, Oto J, Onodera M, Nishimura M. Humidification performance of humidifying devices for tracheostomized patients with spontaneous breathing: a bench study. Respir Care. 2013;58(9):1442-8.,3131 Prat G, Renault A, Tonnelier JM, Goetghebeur D, Oger E, Boles JM, et al. Influence of the humidification device during acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(12):2211-5.,3232 Hinkson CR, Benson MS, Stephens LM, Deem S. The effects of apparatus dead space on P(aCO2) in patients receiving lung-protective ventilation. Respir Care. 2006;51(10):1140-4.,4242 Roux NG, Plotnikow GA, Villalba DS, Gogniat E, Feld V, RiberoVairo N, et al. Evaluation of an active humidification system for inspired gas. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;8(1):69-75.,4343 Roux NG, Feld V, Gogniat E, Villalba D, Plotnikow G, Ribero Vairo N, et al. El frasco humidificador como sistema de humidificación del gas inspirado no cumple con las recomendaciones. Evaluación y comparación de tres sistemas de humidificación. Estudio de laboratorio. Med Intensiva. 2010;27(3).,5151 American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388-416.

52 Klompas M, Branson R, Eichenwald EC, Greene LR, Howell MD, Lee G, et al. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35 Suppl 2:S133-54.

53 Prin S, Chergui K, Augarde R, Page B, Jardin F, Vieillard-Baron A. Ability and safety of a heated humidifier to control hypercapnic acidosis in severe ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(12):1756-60.

54 Morán I, Bellapart J, Vari A, Mancebo J. Heat and moisture exchangers and heated humidifiers in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Effects on respiratory mechanics and gas exchange. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(4):524-31.

55 Parrilla FJ, Morán I, Roche-Campo F, Mancebo J. Ventilatory strategies in obstructive lung disease. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35(4):431-40.

56 Iotti GA, Olivei MC, Braschi A. Mechanical effects of heat- moisture exchangers in ventilated patients. Crit Care. 1999;3(5):R77-82.

57 Girault C, Breton L, Richard JC, Tamion F, Vandelet P, Aboab J, et al. Mechanical effects of airway humidification devices in difficult to wean patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(5):1306-11.

58 McCall JE, Cahill TJ. Respiratory care of the burn patient. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2005;26(3):200-6.

59 Lellouche F, Qader S, Taille S, Lyazidi A, Brochard L. Under-humification and over-humidification during moderate induced hypothermia with usual devices. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(7):1014-21.

60 Oto J, Nakataki E, Okuda N, Onodera M, Imanaka H, Nishimura M. Hygrometric properties of inspired gas and oral dryness in patients with acute respiratory failure during noninvasive ventilation. Respir Care. 2014;59(1):39-45.-6161 Nava S, Navalesi P, Gregoretti C. Interfaces and humidification for noninvasive mechanical ventilation. Respir Care. 2009;54(1):71-84) Enumeramos a continuación algunas situaciones clínicas para considerar:

-

- Síndrome de Distrés Respiratorio Agudo: La estrategia ventilatoria de protección pulmonar utiliza bajos VC (4 a 6 mL/kg de peso corporal predicho), esto trae aparejado el riesgo de generar hipercapnia por hipoventilación. Resulta racional disminuir al máximo el espacio muerto instrumental para contrarrestar este efecto adverso. Una estrategia fácil de implementar es el uso de humidificadores activos en estas situaciones.(3131 Prat G, Renault A, Tonnelier JM, Goetghebeur D, Oger E, Boles JM, et al. Influence of the humidification device during acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(12):2211-5.,3232 Hinkson CR, Benson MS, Stephens LM, Deem S. The effects of apparatus dead space on P(aCO2) in patients receiving lung-protective ventilation. Respir Care. 2006;51(10):1140-4.,5353 Prin S, Chergui K, Augarde R, Page B, Jardin F, Vieillard-Baron A. Ability and safety of a heated humidifier to control hypercapnic acidosis in severe ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(12):1756-60.,5454 Morán I, Bellapart J, Vari A, Mancebo J. Heat and moisture exchangers and heated humidifiers in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Effects on respiratory mechanics and gas exchange. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(4):524-31.)

-

- Neumonía Asociada a la Ventilación Mecánica (NAVM): La reducción en la tasa de NAVM se ve influenciada por la adopción de un paquete de medidas y los sistemas de humidificación no forman parte de ella (CDC 2014); motivo por el cual se recomienda no basar la selección del dispositivo de humidificación en relación al control de infecciones.(5151 American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388-416.,5252 Klompas M, Branson R, Eichenwald EC, Greene LR, Howell MD, Lee G, et al. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35 Suppl 2:S133-54.)

-

- VMNi: Los altos flujos que alcanzan los equipos utilizados y las fugas predisponen a la pérdida de calor y humedad durante el ciclo respiratorio. La humidificación incrementa las chances de éxito en la aplicación de VMNi, ya que se relaciona con la capacidad de manejar las secreciones respiratorias e incrementa la sensación de confort. El dispositivo de elección para acondicionar gases en VMNi sería el humidificador activo con ventiladores de flujo continuo y circuito de rama única. En ventiladores microprocesados con circuito de dos ramas, esta recomendación podría discutirse.(6060 Oto J, Nakataki E, Okuda N, Onodera M, Imanaka H, Nishimura M. Hygrometric properties of inspired gas and oral dryness in patients with acute respiratory failure during noninvasive ventilation. Respir Care. 2014;59(1):39-45.,6161 Nava S, Navalesi P, Gregoretti C. Interfaces and humidification for noninvasive mechanical ventilation. Respir Care. 2009;54(1):71-84)

-

- Ventilación espontánea y vía aérea artificial: En pacientes con traqueostomía (sin VMi) se aconseja de primera línea utilizar los HME correspondientes (considerar sus limitaciones). En caso de que esté contraindicado, utilizar los sistemas de humidificadores activos con una temperatura del agua en la carcasa no menor a 53°C.(4242 Roux NG, Plotnikow GA, Villalba DS, Gogniat E, Feld V, RiberoVairo N, et al. Evaluation of an active humidification system for inspired gas. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;8(1):69-75.,4343 Roux NG, Feld V, Gogniat E, Villalba D, Plotnikow G, Ribero Vairo N, et al. El frasco humidificador como sistema de humidificación del gas inspirado no cumple con las recomendaciones. Evaluación y comparación de tres sistemas de humidificación. Estudio de laboratorio. Med Intensiva. 2010;27(3).)

CONCLUSIONES

El conocimiento de las especificaciones técnicas, ventajas y desventajas de cada uno de los dispositivos de humidificación es esencial para los profesionales que prestan atención a pacientes en la sala de cuidados intensivos. El acondicionamiento de los gases inspirados representa una intervención clave en pacientes con vía aérea artificial y se ha transformado en un cuidado estándar. La selección incorrecta del dispositivo o la configuración inapropiada pueden impactar negativamente en los resultados clínicos al dañar la mucosa de la vía aérea, aumentar el trabajo respiratorio o prolongar la ventilación mecánica invasiva.

REFERENCIAS

-

1Lindemann J, Leiacker R, Rettinger G, Keck T. Nasal mucosal temperature during respiration. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2002;27(3):135-9.

-

2Keck T, Leiacker R, Riechelmann H, Rettinger G. Temperature profile in the nasal cavity. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(4):651-4.

-

3Walker AK, Bethune DW. A comparative study of condenser humidifiers. Anaesthesia. 1976;31(8):1086-93.

-

4Mercke U. The influence of temperature on mucociliary activity. Temperature range 40 degrees C to 50 degrees C. Acta Otolaryngol. 1974;78(3-4):253-8.

-

5Burton JD. Effects of dry anaesthetic gases on the respiratory mucous membrane. Lancet. 1962;1(7223):235-8.

-

6Rathgeber J, Kazmaier S, Penack O, Züchner K. Evaluation of heated humidifiers for use on intubated patients: a comparative study of humidifying efficiency, flow resistance, and alarm functions using a lung model. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(6):731-9.

-

7Déry R. The evolution of heat and moisture in the respiratory tract during anaesthesia with a non-rebreathing system. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1973;20(3):296-309.

-

8Lucato JJ, Adams AB, Souza R, Torquato JA, Carvalho CR, Marini JJ. Evaluating humidity recovery efficiency of currently available heat and moisture exchangers: a respiratory system model study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64(6):585-90.

-

9American Association for Respiratory Care, Restrepo RD, Walsh BK. Humidification during invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation: 2012. Respir Care. 2012;57(5):782-8.

-

10Branson RD, Campbell RS, Davis K, Porembka DT. Anaesthesia circuits, humidity output, and mucociliary structure and function. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1998;26(2):178-83.

-

11Forbes AR. Temperature, humidity and mucus flow in the intubated trachea. Br J Anaesth. 1974;46(1):29-34.

-

12Wiesmiller K, Keck T, Leiacker R, Lindemann J. Simultaneous in vivo measurements of intranasal air and mucosal temperature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264(6):615-9.

-

13Keck T, Leiacker R, Heinrich A, Kühnemann S, Rettinger G. Humidity and temperature profile in the nasal cavity. Rhinology. 2000;38(4):167-71.

-

14Pillow JJ, Hillman NH, Polglase GR, Moss TJ, Kallapur SG, Cheah FC, et al. Oxygen, temperature and humidity of inspired gases and their influences on airway and lung tissue in near-term lambs. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(12):2157-63.

-

15Uchiyama A, Yoshida T, Yamanaka H, Fujino Y. Estimation of tracheal pressure and imposed expiratory work of breathing by the endotracheal tube, heat and moisture exchanger, and ventilator during mechanical ventilation. Respir Care. 2013;58(7):1157-69.

-

16Eckerbom B, Lindholm CE. Performance evaluation of six heat and moisture exchangers according to the Draft International Standard (ISO/DIS 9360). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34(5):404-9.

-

17Cohen IL, Weinberg PF, Fein IA, Rowinski GS. Endotracheal tube occlusion associated with the use of heat and moisture exchangers in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1988;16(3):277-9.

-

18Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.

-

19Martin C, Papazian L, Perrin G, Saux P, Gouin F. Preservation of humidity and heat of respiratory gases in patients with a minute ventilation greater than 10 L/min. Crit Care Med. 1994;22(11):1871-6.

-

20Martin C, Thomachot L, Quinio B, Viviand X, Albanese J. Comparing two heat and moisture exchangers with one vaporizing humidifier in patients with minute ventilation greater than 10 L/min. Chest. 1995;107(5):1411-5.

-

21Unal N, Kanhai JK, Buijk SL, Pompe JC, Holland WP, Gültuna I, et al. A novel method of evaluation of three heat-moisture exchangers in six different ventilator settings. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24(2):138-46.

-

22Wilkes AR. Heat and moisture exchangers. Structure and function. Respir Care Clin N Am. 1998;4(2):261-79.

-

23Lee MG, Ford JL, Hunt PB, Ireland DS, Swanson PW. Bacterial retention properties of heat and moisture exchange filters. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69(5):522-5.

-

24Boyer A, Thiéry G, Lasry S, Pigné E, Salah A, de Lassence A, et al. Long-term mechanical ventilation with hygroscopic heat and moisture exchangers used for 48 hours: a prospective clinical, hygrometric, and bacteriologic study. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(3):823-9.

-

25Turnbull D, Fisher PC, Mills GH, Morgan-Hughes NJ. Performance of breathing filters under wet conditions: a laboratory evaluation. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94(5):675-82.

-

26Davis K Jr, Evans SL, Campbell RS, Johannigman JA, Luchette FA, Porembka DT, et al. Prolonged use of heat and moisture exchangers does not affect device efficiency or frequency rate of nosocomial pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(5):1412-8.

-

27Le Bourdellès G, Mier L, Fiquet B, Djedaïni K, Saumon G, Coste F, et al. Comparison of the effects of heat and moisture exchangers and heated humidifiers on ventilation and gas exchange during weaning trials from mechanical ventilation. Chest. 1996;110(5):1294-8.

-

28Campbell RS, Davis K Jr, Johannigman JA, Branson RD. The effects of passive humidifier dead space on respiratory variables in paralyzed and spontaneously breathing patients. Respir Care. 2000;45(3):306-12.

-

29Chikata Y, Oto J, Onodera M, Nishimura M. Humidification performance of humidifying devices for tracheostomized patients with spontaneous breathing: a bench study. Respir Care. 2013;58(9):1442-8.

-

30Brusasco C, Corradi F, Vargas M, Bona M, Bruno F, Marsili M, et al. In vitro evaluation of heat and moisture exchangers designed for spontaneously breathing tracheostomized patients. Respir Care. 2013;58(11):1878-85.

-

31Prat G, Renault A, Tonnelier JM, Goetghebeur D, Oger E, Boles JM, et al. Influence of the humidification device during acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(12):2211-5.

-

32Hinkson CR, Benson MS, Stephens LM, Deem S. The effects of apparatus dead space on P(aCO2) in patients receiving lung-protective ventilation. Respir Care. 2006;51(10):1140-4.

-

33International Standardization Organization (ISO). Anaesthetic and respiratory equipment - Heat and moisture exchangers (HMEs) for humidifying respired gases in humans - Part 2: HMEs for use with tracheostomized patients having minimum tidal volumes of 250 ml. EN ISO 9360-2:2009, ISO 9360-2:2001. Available from: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:9360:-2:ed-1:v1:en

» https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:9360:-2:ed-1:v1:en -

34Lucato JJ, Tucci MR, Schettino GP, Adams AB, Fu C, Forti G Jr, et al. Evaluation of resistance in 8 different heat-and-moisture exchangers: effects of saturation and flow rate/profile. Respir Care. 2005;50(5):636-43.

-

35Chiaranda M, Verona L, Pinamonti O, Dominioni L, Minoja G, Conti G. Use of heat and moisture exchanging (HME) filters in mechanically ventilated ICU patients: influence on airway flow-resistance. Intensive Care Med.1993;19(8):462-6.

-

36Lellouche F, Qader S, Taillé S, Lyazidi A, Brochard L. Influence of ambient temperature and minute ventilation on passive and active heat and moisture exchangers. Respir Care. 2014;59(5):637-43.

-

37Thomachot L, Boisson C, Arnaud S, Michelet P, Cambon S, Martin C. Changing heat and moisture exchangers after 96 hours rather than after 24 hours: a clinical and microbiological evaluation. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(3):714-20.

-

38Ricard JD, Le Mière E, Markowicz P, Lasry S, Saumon G, Djedaïni K, et al. Efficiency and safety of mechanical ventilation with a heat and moisture exchanger changed only once a week. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(1):104-9.

-

39Thomachot L, Leone M, Razzouk K, Antonini F, Vialet R, Martin C. Randomized clinical trial of extended use of a hydrophobic condenser humidifier: 1 vs. 7 days. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1):232-7.

-

40Roustan JP, Kienlen J, Aubas P, Aubas S, du Cailar J. Comparison of hydrophobic heat and moisture exchangers with heated humidifier during prolonged mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 1992;18(2):97-100.

-

41Oh TE, Lin ES, Bhatt S. Resistance of humidifiers, and inspiratory work imposed by a ventilator-humidifier circuit. Br J Anaesth. 1991;66(2):258-63.

-

42Roux NG, Plotnikow GA, Villalba DS, Gogniat E, Feld V, RiberoVairo N, et al. Evaluation of an active humidification system for inspired gas. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;8(1):69-75.

-

43Roux NG, Feld V, Gogniat E, Villalba D, Plotnikow G, Ribero Vairo N, et al. El frasco humidificador como sistema de humidificación del gas inspirado no cumple con las recomendaciones. Evaluación y comparación de tres sistemas de humidificación. Estudio de laboratorio. Med Intensiva. 2010;27(3).

-

44Ari A, Alwadeai KS, Fink JB. Effects of heat and moisture exchangers and exhaled humidity on aerosol deposition in a simulated ventilator-dependent adult lung model. Respir Care. 2017;62(5):538-43.

-

45Thomachot L, Viviand X, Boyadjiev I, Vialet R, Martin C. The combination of a heat and moisture exchanger and a Booster: a clinical and bacteriological evaluation over 96 h. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(2):147-53.

-

46Pelosi P, Severgnini P, Selmo G, Corradini M, Chiaranda M, Novario R, et al. In vitro evaluation of an active heat-and-moisture exchanger: the Hygrovent Gold. Respir Care. 2010;55(4):460-6.

-

47Branson RD, Campbell RS, Johannigman JA, Ottaway M, Davis K Jr, Luchette FA, et al. Comparison of conventional heated humidification with a new active hygroscopic heat and moisture exchanger in mechanically ventilated patients. Respir Care. 1999;44(8):912-7.

-

48Siempos II, Vardakas KZ, Kopterides P, Falagas ME. Impact of passive humidification on clinical outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(12):2843-51.

-

49Kelly M, Gillies D, Todd DA, Lockwood C. Heated humidification versus heat and moisture exchangers for ventilated adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(4):CD004711.

-

50Branson RD. Humidification for patients with artificial airways. Respir Care. 1999;44(6):630-41.

-

51American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388-416.

-

52Klompas M, Branson R, Eichenwald EC, Greene LR, Howell MD, Lee G, et al. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35 Suppl 2:S133-54.

-

53Prin S, Chergui K, Augarde R, Page B, Jardin F, Vieillard-Baron A. Ability and safety of a heated humidifier to control hypercapnic acidosis in severe ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(12):1756-60.

-

54Morán I, Bellapart J, Vari A, Mancebo J. Heat and moisture exchangers and heated humidifiers in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Effects on respiratory mechanics and gas exchange. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(4):524-31.

-

55Parrilla FJ, Morán I, Roche-Campo F, Mancebo J. Ventilatory strategies in obstructive lung disease. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35(4):431-40.

-

56Iotti GA, Olivei MC, Braschi A. Mechanical effects of heat- moisture exchangers in ventilated patients. Crit Care. 1999;3(5):R77-82.

-

57Girault C, Breton L, Richard JC, Tamion F, Vandelet P, Aboab J, et al. Mechanical effects of airway humidification devices in difficult to wean patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(5):1306-11.

-

58McCall JE, Cahill TJ. Respiratory care of the burn patient. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2005;26(3):200-6.

-

59Lellouche F, Qader S, Taille S, Lyazidi A, Brochard L. Under-humification and over-humidification during moderate induced hypothermia with usual devices. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(7):1014-21.

-

60Oto J, Nakataki E, Okuda N, Onodera M, Imanaka H, Nishimura M. Hygrometric properties of inspired gas and oral dryness in patients with acute respiratory failure during noninvasive ventilation. Respir Care. 2014;59(1):39-45.

-

61Nava S, Navalesi P, Gregoretti C. Interfaces and humidification for noninvasive mechanical ventilation. Respir Care. 2009;54(1):71-84

Editado por

Fechas de Publicación

-

Publicación en esta colección

Mar 2018

Histórico

-

Recibido

29 Mayo 2017 -

Acepto

30 Ago 2017

Fuente: Basado en los datos del artículo: Eckerbom B, Lindholm CE. Performance evaluation of six heat and moisture exchangers according to the Draft International Standard (ISO/DIS 9360). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34(5):404-9.(

Fuente: Basado en los datos del artículo: Eckerbom B, Lindholm CE. Performance evaluation of six heat and moisture exchangers according to the Draft International Standard (ISO/DIS 9360). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34(5):404-9.( Fuente: Basado en los datos del artículo: Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.(

Fuente: Basado en los datos del artículo: Branson R, Davis K Jr. Evaluation of 21 passive humidifiers according to the ISO 9360 standard: moisture output, dead space, and flow resistance. Respir Care. 1996;41:736-43.(