Abstract

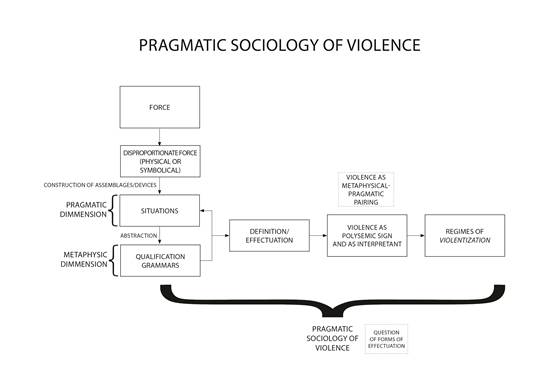

In this article we propose a model for a pragmatic sociology of violence. Based on a semiotic analysis of a primordial cognitive operation deployed in people’s definition of situations, namely qualification, the essential characterization of things, the paper maps the meanings attributed to what both ordinary social actors and academic analysts treat as violence. Our analysis shows that this operation imbues a concrete object with meaning, the disproportionate use of force, whose resignifications compose a typology of five ‘sociologies of violence,’ both native and academic. These are: substantivist, constructivist, political, critical, and praxiological. To this gallery, we suggest the addition of another item: a pragmatic sociology. Taking the sign ‘violence’ as an interpretant, this sociology seeks to understand how, in people’s qualifications, it functions as a connection between moral metaphysics (worldviews in which the deployment of disproportionate force makes sense) and devices capable of effectuating them.

Keywords:

violence; disproportionate force; pragmatism; pragmatic sociology of violence; conflict

Resumo

O objetivo deste artigo é propor uma sociologia pragmática da violência. A partir de uma semiótica de uma operação cognitiva primordial contida nas definições de situação, a qualificação, caracterização fundamental das coisas, mapeamos os sentidos atribuídos àquilo que atores sociais em geral (e analistas em particular) tratam como violência. Observamos que essa operação preenche de sentido um objeto concreto, a força desproporcional, cujas ressignificações compõem uma tipologia de cinco “sociologias da violência”, tanto nativas quanto analíticas: uma substantivista; uma construtivista; uma política; uma crítica; e uma praxiológica. A esse quadro, sugerimos acrescentar uma sociologia pragmática: nela, a partir do entendimento do signo violência como um interpretante, buscamos compreender como, nas operações de qualificação, ele serve de elo entre metafísicas morais (formas de ver o mundo nas quais faz sentido o uso da força desproporcional) e dispositivos capazes de as atualizar.

Palavras-chave:

violência; força desproporcional; pragmatismo; sociologia pragmática da violência; conflito.

To say that violence is one of the most complex questions not only of contemporary sociological theory but even of the entire discipline since its origins is now virtually a truism. The bibliographic reviews on the theme - for instance, Campos & Alvarez (2018CAMPOS, Marcelo da S.; ALVAREZ, Marcos César. Políticas públicas de segurança, violência e punição no Brasil (2000-2016). In: MICELI, Sergio; MARTINS, Carlos Benedito (eds.). Sociologia brasileira hoje. São Paulo: Ateliê Editorial, 2018, p. 143-216.), for Brazil, and Imbusch, Misse & Carrión (2011IMBUSCH, Peter; MISSE, Michel; CARRIÓN, Fernando. Violence research in Latin America and the Caribbean: a literature review. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, v. 5, n. 1, p. 87-154, 2011.), for the whole of Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as Nóbrega Júnior (2015NÓBREGA JÚNIOR, José Maria P. da. Teorias do crime e da violência: uma revisão da literatura. Revista Brasileira de Informação Bibliográfica em Ciências Sociais (BIB), n. 77 (1/2014), p. 69-89, 2015.) and Ratton (2017RATTON, José Luiz. Crime, polícia e sistema de justiça no Brasil contemporâneo: uma cartografia (incompleta) dos consensos e dissensos da produção recente das ciências sociais. Revista Brasileira de Informação Bibliográfica em Ciências Sociais (BIB), n. 84 (2/2017), p. 5-12, 2017.) - typically call attention to this complexity and, simultaneously, take it as a given consensus. Likewise, theoretical essays dedicated to the definition of violence as a concept habitually set out from the same observation - here we can note the endeavors of Imbusch (2003)IMBUSCH, Peter. The concept of violence. In: HEITMEYER, Wilhelm; HAGAN, John (eds.). International handbook of violence research. New York: Kluwer, 2003, p. 13-39., Wieviorka (2004WIEVIORKA, Michel. La violence: voix et regards. Les Plans sur Bex (Switzerland): Balland, 2004.), Collins (2008COLLINS, Randall. Violence: a microsociological theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.), Schinkel (2010SCHINKEL, Willem. Aspects of violence: a critical theory. Kent: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.), Zucal & Noel (2010ZUCAL, José G.; NOEL, Gabriel. Notas para una definición antropológica de la violencia: un debate en curso. Publicar, v. 8, n. 9, p. 97-121, 2010.), Michaud (2012MICHAUD, Yves. La violence. Paris: PUF, 2012.), Misse (2016) MISSE, Michel. Violência e teoria social. Dilemas: Revista de Estudos de Conflito e Controle Social, v.9, n. 1, p. 45-63, 2016.and Saborío (2019SABORÍO, Sebastián. Violencia urbana: análisis crítico y limitaciones del concepto. Revistarquis, v. 8, n. 1, p. 61-71, 2019. https://doi.org/10.15517/ra.v8i1.35798

https://doi.org/10.15517/ra.v8i1.35798...

) - also underlining its obviousness. Nevertheless, the bases of this obviousness are hidden, routinized under the guise of the multiplicity at play within it. At the core, it comprises a semiotic issue: polysemic and multidimensional, the sign ‘violence’ attempts to account for very distinct aspects of objective reality, across many different registers, both for academics and common social actors.

Close observation of these and various other descriptions, alongside with what we have seen in our fieldwork, both separately and collectively, on urban violence in Rio de Janeiro2 2 See: Teixeira (2011a; 2011b; 2013; 2015), Freire & Teixeira (2019), Werneck (2011; 2015a; 2015c; 2019b), Talone (2015a; 2015b; 2017; 2019), Werneck & Talone (2019). and on the sociology of morality3 3 See: Werneck (2012b; 2014b; 2015b) and Talone (2015a). , as well as in the work of authors who have inspired us on this journey - especially Michel Misse, Luiz Antônio Machado da Silva, Maria Stela Grossi Porto and Alba Zaluar, all cited in due course - and in the recent studies of colleagues with whom we actively dialogue on this problematic in Brazil4 4 Particularly, Cavalcanti (2008), Marques (2009), Sá (2010), Hirata (2010), Lyra (2010), Feltran (2011), Grillo (2008; 2013; 2014), Freire (2010; 2014), Corrêa (2015), Franco (2014), França (2015; 2019) and Menezes (2015). , allows us to make explicit an initial point to uncover this semiosis: in the vast majority of analyses (of researchers or common actors in their practical life), this complex sign seems to serve rather as a metonym than a simple substantive in its own terms: in modern life, violence appears to signify (i.e., takes the place of) social conflict (Horowitz, 1962HOROWITZ, Irving Louis. Consensus, conflict and cooperation: a sociological inventory. Social Forces, v. 41, n. 2, p. 177-188, 1962.; Misse; Werneck, 2012WERNECK, Alexandre. A contribuição de uma abordagem pragmatista da moral para a sociologia do conflito. In: MISSE, Michel; WERNECK, Alexandre (eds.). Conflitos de (grande) interesse: estudos sobre crimes, violências e outras disputas conflituosas. Rio de Janeiro: Garamond, p. 337-354, 2012b.) and, when the latter is intermediated by the legal structure, crime. Most of the time, it is these objects of the real world and their various, equally multiple meanings that this idea - more a wild card than an objective fact - is addressing when it is used to define what is happening. As observed in practice, the most typical discourses and behaviors relating to what people qualify as violence refer to these two phenomena, given that this term more often seems to indicate, as Michel Misse (2016; 2017MISSE, Michel. Violência e teoria social: uma nova agenda? In: ROJAS, Carlos del V.; ECHETO, Victor S. (eds.). Crisis, comunicación y crisis política. Quito: Ciespal, 2017, p. 213-233.) and others have clearly shown, the typically modern social interdiction projected onto them.

However, this same reflection led us to realize that the sign in question, though referring metonymically to the privileged social forms of conflict and crime, also belongs with them to a set of substitutes for an even more fundamental object. All these signifiers at root appear to serve as an alias for the same thing, one more clearly observable in practice: disproportionate force. It is the use of force, an objective entity, and in a comparative condition, which is ultimately in play when the idea of violence is mobilized. And as we continued to deepen our observations and dissect their operational processes, we also realized that this primary metonymization produced, when put into practice, a diverse range of definitions. But instead of encountering an uncontrolled polysemy in our research, we perceived a plural framework of qualifications - that is, a more or less finite gallery (although potentially expanding, depending on new empirical findings) of understandings of what people mean when they say ‘violence.’ From the viewpoint of its foundation, therefore, these constitute different forms of qualifying disproportional force, in varying situations and with diverse meanings and implications.

We discuss these different definitions further on. For now, it is essential to observe that this series of perceptions persuaded us to focus our analysis on how the formal dimension of the idea of violence emerges at the epicenter of this plural framework, with each of these interpretations comprising a worldview, indicative of a native theory of how disproportionate force is usually or should be applied, representing the same entity, an interpretant (Peirce, 1977PEIRCE, Charles S. Divisão dos signos. In: Semiótica. São Paulo: Perspectiva , 1977(1897), p. 45-61.b(1897)). Consequently, we were inevitably induced to regard this phenomenon with the pragmatist and interpretative eyes that have tended to guide our individual and joint studies5 5 Teixeira (2011b; 2012; 2013), Werneck (2012a; 2014b) and Talone (2015a). , eventually foregrounding two analytic stances that enable us to comprehend complex elements previously overlooked in this discussion. The first, that the phenomenon in play, when actors point to something and say ‘violence’, involves a definition of the situation (Thomas, 1969THOMAS, William I. The unadjusted girl: with cases and standpoint for behaviour analysis. Monclair (USA): Patterson Smith, 1969(1923).(1923)), associating a cognitive operation fundamental to these definitions, the qualification - the basic characterization of what they encounter in their everyday lives - with the component role of recognizing what is happening within a given instance of time and space (thus, a situated event). The second, that these different worldviews correspond to different metaphysics of these situations, composing with elements of the latter - subsequently treated as devices made by the actors to account for them - a metaphysical-pragmatic pairing: that is, a signification system that corresponds to the form in which actors attribute meaning to what happens in the world (Peirce, 1977(1893); Weber, 1947WEBER, Max. The theory of social and economic organization. Glencoe (USA): The Free Press, 1947(1922).(1922)).

Based on this entire empirical and analytic trajectory, our aim in this article is to outline the bases for a model of a pragmatic sociology of violence - in other words, a treatment capable of accounting for the various ways in which social actors operate a coupling between different fundamental metaphysics and a practical world in which this sign occurs. Consequently, this sociology seeks to understand (Weber, 1947WEBER, Max. The theory of social and economic organization. Glencoe (USA): The Free Press, 1947(1922).(1922)) how people put into operation the definition or qualification of a specific and recurrent situation in social life: one in which they encounter a disproportionate deployment of force. This will allow us to map the meanings attributed to what social actors in general (scholars included) call violence and, based on this, also map the different abstract frameworks to which we referred earlier, the different metaphysics that guide and found their behaviors, and, continuing our analysis, explore the relationship between these frameworks and the devices constructed by people to effectuate (Werneck, 2012WERNECK, Alexandre. A contribuição de uma abordagem pragmatista da moral para a sociologia do conflito. In: MISSE, Michel; WERNECK, Alexandre (eds.). Conflitos de (grande) interesse: estudos sobre crimes, violências e outras disputas conflituosas. Rio de Janeiro: Garamond, p. 337-354, 2012b.a) these situations based on these - what we can call - violentized worldviews.6 6 Ultimately this confirms a classic assertion of the Brazilian sociology of violence, encapsulated in the assertions of Michel Misse (1999, p. 39) that “‘violence’ does not exist, but rather violences, multiple, plural, in different degrees of visibility, abstraction, and definition of its alterities” and of Zaluar (1997) that violence has a “multidimensional character.” However, since violence is “everywhere, it has neither permanently recognizable social actors nor easily delimitable and intelligible ‘causes’” (Zaluar, 1998, p. 6); consequently, researchers must consider what the people affected by different kinds of violence think, including their own descriptions and the violations of the groups to which they belong (Zaluar, 2009).

The adoption of a pragmatic and interpretative approach also enables us to access another fundamental dimension. As we have already shown in other works7 7 Werneck (2012b; 2019a; 2019b), Werneck & Loretti (2018), Talone (2015a; 2015b). , this framing is ideally suited to producing a sociology of morality (Werneck, 2014WERNECK, Alexandre. Sociologia da moral, agência social e criatividade. In: WERNECK, Alexandre; CARDOSO DE OLIVEIRA, Luis Roberto (eds.). Pensando bem: estudos de Sociologia e Antropologia da Moral. Rio de Janeiro: Casa da Palavra , 2014b, p. 25-48.b). This, in turn, enables us to discern a sociology of violence as a sociology of moralities: the metaphysics observed do not comprise pure operational frames for social action (Goffman, 2012GOFFMAN, Erving. Os quadros da experiência social: uma perspectiva de análise. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2012(1974).(1974)); rather, they emerge as valuative repertoires, moral grammars, making explicit competences and, therefore, operating as regimes (Boltanski, 1990BOLTANSKI, Luc. L’amour et la justice comme compétences: trois essais de sociologie de l’action. Paris: Métailié, 1990.) capable of effectuating situations based on determined targetings of the good to determined elements of these same situations (Werneck, 2012a, pp. 300-313WERNECK, Alexandre. A desculpa: as circunstâncias e a moral das relações sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2012a.). It is through this approach that ‘violence’, as we stated, becomes an interpretant - that is, a specific logic of interconnection between representamens (pragmatics) and objects (metaphysics) (Peirce, 1977PEIRCE, Charles S. Divisão dos signos. In: Semiótica. São Paulo: Perspectiva , 1977(1897), p. 45-61.(1897)). But more than this, it becomes a specific type of interconnector, an outcome of the friction between a moral metaphysics and actual practices. In this case, therefore, this link translates into a vision of how disproportionate force is valued/evaluated and of the situations that can be typically associated with it.

This treatment thus seeks to shift focus of the analysis of violence, both in its positivity as a thing - frequently considered self-evident by academic analysts and common social actors - and in its effects as a positivity on social relations, to the foundations of the construction of worlds (Boltanski; Thévenot, 2020BOLTANSKI, Luc; THÉVENOT, Laurent. A justificação: sobre as economias da grandeza. Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ, 2020(1991).(1991)) in which violence is represented (and naturalized) as a positivity. Put succinctly, we aim to analyze the logical and valuative bases of the idea of violence serving people as a natural core of situations and their effects on social life.8 8 In another work, Werneck & Talone (2019) put this framing into practice through an analysis of Luiz Antônio Machado da Silva’s idea of violent sociability. According to the authors, this sociability suggested as emergent by Machado da Silva (1993; 1995; 1999; 2004; 2010; 2011; 2014) involves the coordinated effect of three grammars identified here as a substantivist sociology of violence, a critical sociology of violence, and a constructivist sociology of violence.

The fundamental metaphysics or moral grammars to which we refer, which define these worlds and correspond to distinct semiotic frameworks fundamental to the meaning of the term violence, was approached in our research studies as sociologies - that is, as theories about social life. This does not mean, though, that our analysis is reduced to a sociology of sociology - or to a mere bibliographic review. As we announced earlier, our work turned to the qualifications made by both academic analysts and everyday social actors. This amounts to saying that we symmetrize these two forms of analysis in our interpretation, comprehending both as analytic attitudes, as operations of constructing theories (whether analytic or native). This perspective was essential to conceptualizing the representation of the actors concerning the central role performed by the idea of violence in their visions of the social, which defines not only analytic attitudes but also actions (Latour, 1984LATOUR, Bruno. Les microbes: guerre et paix. Paris: Éditions Anne-Marie Métailié, 1984.; 1997(1987); Callon; Latour, 1981CALLON, Michel; LATOUR, Bruno. Unscrewing the big Leviathan: how actors macro-structure reality and how sociologists help them to do so. In: KNORR-CETINA, Karin; CICOUREL, Aaron V. (eds.). Toward an integration of micro- and macro- sociologies. Boston/London: Routledge/Keegan Paul, 1981. p. 277-303.).

However, there is also an important form of theorization to be considered: somewhere between descriptive academic theory (whose purpose is to produce a fully objective and explanatory image of reality) and operative native theory (whose purpose is to produce an image of reality capable of accounting for the operations at work), we can discern a third: a normative ethical theorization (whose purpose is to produce a utopia of reality, extrapolating from this an ideal version as a project to be put into practice). This confers the description of social life the contours of a political philosophy (Chanial, 2011CHANIAL, Philippe. La sociologie comme philosophie politique et réciproquement. Paris: La Decouverte, 2011.) in which what is described is not what the world is like scientifically or practically, but how the world should be. Registering this modality of interpretation led us to perceive how, for the actors concerned, a theoretical framework is an ontological form, showing how they adopt worldviews to frame the world and how the analysis pursued here is a sociology of theories of the social that set violence in play and, therefore, a sociology of the choice of different valuative frameworks based on a view of how the world should function.

Speaking of ‘sociologies’, thus, enabled us to attribute social actors precedence over the (moral) semiotics of ‘violence’ and dislocates us to the outside of this mechanics, in a dynamic of isolating the naturalization of the metaphysics thought/put into practice by the actors. At the same time, it allowed us to perceive the mobility fostered by these same actors between sociologies, tracing a universe of diverse worlds, mobilized situationally. This made explicit a multivalorative social life in which different interpretations of its functioning coexist in dissensual and dissonant forms (Stark, 2009STARK, David. The sense of dissonance: accounts of worth in economic life. Princeton: Princeton University Press , 2009.), effectuating potentially productive frictions between them and, equally, coordinated associations between their descriptions, as it can be seen more clearly when we analyze the established academic approaches.9 9 Thus, for example, in the same way as Machado da Silva’s ‘violent sociability’ could be translated into these terms (see the previous note), Misse’s approach to criminal subjection and the social accumulation of violence (Misse, 1997; 1999; 2008) can be described as a combination of constructivist sociology and critical sociology. The same applies to the approach of Collins (2008) as a combination of constructivist sociology and praxiological sociology. Equally, though, the descriptions made by the actors studied by Teixeira (2012) in his research compose a constructivist sociology of a substantivist kind.

This pragmatist option, based on the consequentialism of Peirce (1977PEIRCE, Charles S. Divisão dos signos. In: Semiótica. São Paulo: Perspectiva , 1977(1897), p. 45-61.(1893)) and its impact on the situationism of Thomas (1969THOMAS, William I. The unadjusted girl: with cases and standpoint for behaviour analysis. Monclair (USA): Patterson Smith, 1969(1923).(1923)), establishes an epistemological condition: our analysis considers the consequences produced by the definitions of a situation as indices of these same definitions. This means that the variable in play here are the behaviors of the actors and that our hypothesis is that these behaviors are indicative of the forms in which they define a situation. From this viewpoint, the reflexivity of the actors involved matters little. Equally, it is irrelevant whether this is mentally self-perceptible: “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences” (Thomas & Thomas, 1938THOMAS, William I; THOMAS, Dorothy Swaine. The child in America: behavior problems and programs. New York: A. A. Knopf, 1938(1928).(1928), p. 572). In other words, if they define a situation as A, it will be A if, as they behave as in A, they can act effectively as in A. This means that an adjustment is needed between the interpretations not only of the people involved but also of the things involved (the situation “needs to agree” that it is what it is thought to be in order for correspondent consequences to be generated). As a result, our observations gathered not just verbalized descriptions of a situation as violent (although this is included in the analyzable universe) but also an entire range of actions that enables us to infer that a situation is treated as ‘violent’. Thus, when Werneck analyses the construction of the image of militia members in a parliamentary inquiry (2015WERNECK, Alexandre (ed.). Violências moduladas: gramáticas e dispositivos da crítica e da negociação na conflitualidade urbana no Rio de Janeiro. Research report, Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Faperj), 2015c.a) or the depictions of the police, drug dealers and Rio de Janeiro city itself in a popular newspaper (2019b), the focus is on the approximation of these actions as a same type of consequence, a same, disproportionate, response to actions, whether or not this is explicitly called violence by the actors: it is the latter’s reactions that tell us whether a violentized treatment is involved. Similarly, when Teixeira analyses the problematic relationship of religious converts to their previous lives in crime, whether in Evangelical churches (2011a, 2011b) or in rehabilitation centers (2016), the analysis focuses on the dynamic of transformation of a moral filter, that we can call violentized, not always made explicit reflexively by actors themselves. And likewise, when Talone (2015TALONE, Vittorio da G. O ‘quadro da perturbação’: a rota de conflitos nos trajetos de ônibus do Rio de Janeiro. Cadernos de Estudos Sociais e Políticos, v. 4, n. 8, p. 87-108, 2015b.a; 2015b; 2017; 2018TALONE, Vittorio da G. Evitação e afastamento como dispositivos morais da gramática da desconfiança: Uma leitura pragmatista do deslocamento urbano pela ‘violenta’ cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Dilemas: Revista de Estudos de Conflito e Controle Social, v. 11, n. 1, p.153-172, 2018.) discusses the treatment of Rio de Janeiro as a dystopia, whether in the mistrustful behaviors of bus passengers or in the recollections of situations involving death or near-death (2019), the influence of a violentized representation of an entire social order can be perceived in their behaviors, indicating that the actors treat their own histories as violent.10 10 In order for us to focus on the exposition of the resulting theoretical argument, in this text we have left exposition of the evidence to previously published research (our own and that of colleagues). In addition to these studies, a research effort currently underway is collecting new cases with new texts planned that will describe these regimes in closer detail.

This mode of analysis aligns us with both the classical pragmatism and its more recent versions, especially the pragmatic sociology of critique (Boltanski, 2016BOLTANSKI, Luc. Sociologia crítica e sociologia da crítica. In: VANDENBERGHE, Frédéric; VÉRAN, Jean-François (eds.). Além do habitus: teoria social pós-bourdieusiana. Rio de Janeiro: 7Letras, 2016(1990), p. 129-154.(1990); 2009), proposing to act as a contribution to both these approaches and also to studies of violence and morality. What animates our discussion is, in particular, the problem of the qualifications and/or categorizations as a fundamental operation of defining a situation - a question especially addressed by Boltanski and Thévenot in their joint works (1983; 2020(1991)) and in those of authors like Thévenot (1979)THÉVENOT, Laurent. Une jeunesse difficile: les fonctions sociales du flou et de la rigueur dans les classements. Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales, v. 26-27, p. 3-18, 1979. and Boltanski (1982) BOLTANSKI, Luc. Les cadres: la formation d’un groupe sociale. Paris: Minuit, 1982.themselves, as well as Desrosières & Thévenot (1988DESROSIÈRES, Alain; THÉVENOT, Laurent. Les categories socioprofessionnelles. Paris: Découverte, 1988.), Heinich (2000HEINICH, Nathalie. What is an artistic event? A new approach to the sociological discourse. Boekman Cahier, v. 12, n. 44, p. 159-168, 2000.; 2005HEINICH, Nathalie. L’élite artiste: excellence et singularité en régime démocratique. Paris: Gallimard , 2005.) and, more recently in Brazil, Freire (2010FREIRE, Jussara. Agir no regime de desumanização: esboço de um modelo para análise da sociabilidade urbana na cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Dilemas: Revista de Estudos de Conflito e Controle Social, n. 10 (v. 3, n. 4), p. 119-142, 2010.), Mota (2014MOTA, Fabio Reis. Cidadãos em toda parte ou cidadãos à parte? Demandas de direitos e reconhecimento no Brasil e na França. Rio de Janeiro: Consequência, 2014.), Corrêa (2015CORRÊA, Diogo. Anjos de fuzil: uma etnografia das relações entre igreja e tráfico na cidade de deus. 2015. PhD dissertation, IESP, UERJ, Rio de Janeiro, RS.) and Werneck (2017WERNECK, Alexandre. A antropologia de base do modelo das EG: um agenciamento de capacidades. In: II Seminário Internacional de Sociologia e Antropologia Pragmática no Cone Sul: o acesso ao espaço público em contextos diversos. Niterói, UFF, 2017.).

On force as a fundamental actant and as perceived difference

In classical mechanics, the area of physics devoted to the study of movement at the down-to-earth Newtonian level, force is defined as an entity11 11 The various physics’ manuals and dictionaries consulted vary between the absence of a definition (sometimes treating the concept as given or merely invoking its mathematical expression) and a terminologically variable definition. Force is sometimes an entity, sometimes an agent, sometimes an interaction, sometimes a vector, sometimes ‘something.’ We preferred the term entity because of its broader signification and in order to make explicit the hypothesis that the actors conceive force as a character in the situation. capable of altering a body’s state of inertia, either by altering its condition of rest or uniform motion and/or by causing elastic deformations in flexible objects (D. Van Nostrand, 1956D. VAN NOSTRAND. The international dictionary of Physics and Electronics. Toronto/Princeton/London: D. Van Nostrand, 1956.; Alonso; Finn, 1972ALONSO, Marcelo; FINN, Edward J. Física, um curso universitário, v. 1: Mecânica. São Paulo: Blucher, 1972.; Palgrave Macmillan, 2003PALGRAVE-MACMILLAN. Dictionary of Physics, v. 2. London/New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2003.; Deeson, 2007DEESON, Eric. Collins internet-linked dictionary of Physics. London: Haper Collins, 2007.). Consequently, it is something that can be said objectively to act on things when these are observed to experience such a change of state. Furthermore, as a quantity, force is vectorial: in other words, it combines magnitude with an angular component (the result is dependent on its direction in relation to the observed body at the point of application).12 12 It differs, therefore, from scalar quantities, such as mass or length, the definition of which depends solely on magnitude. Consequently, it has a sign, an angle, and an intensity, and can be measured and compared: we can say that it is applied in greater or lesser intensity in a given situation and/or that there is a disproportion between its investments on either side - since we can speak of an optimal limit to its application, the infinitesimal point after which the inertial resistance of the movable body is overcome (for example, the resistance of the forces of weight and friction, which oppose the force inducing motion to the body).

From the sociological point of view, this framework of physical definitions may trivially make sense if we adopt an approach such as the actantial model, entirely consistent with the approach advocated here. This model was introduced into the social sciences by Bruno Latour (1997LATOUR, Bruno. Ciência em ação: como seguir cientistas e engenheiros sociedade afora. São Paulo: Unesp, 1997(1987).(1987)) through the concept of actant, proposed by the Lithuanian linguist later settled in France, Algirdas Greimas (1976GREIMAS, Algirdas J. Semântica estrutural: pesquisa de método. São Paulo: Cultrix/EdUSP, 1976(1966).(1966)), the architect of a semiotic model dedicated to analyzing narratives, narratology. According to Greimas himself, the actant is whoever or whatever practices an act. More specifically, it is an entity with the observed capacity to determine what occurs in a narration. Moreover, this entity may be of any kind, a person, an animal, an object, an idea.13 13 Latour and Michel Callon (Callon; Latour, 1981) make use of Greimas in the actor-network model in order to logically construct the idea of symmetrization - that is, the treatment of all the entities contained in a situation with the same analytical tools without differentiating them in terms of agency - which allowed Latour to analyze human beings and non-humans within the same framework in the laboratory (Latour, 1984, 1997(1987)). Within this scope, we can think of force as the fundamental actant, the sign of everything that makes something move, makes something happen, the determinant of any situation (if someone or something determines what occurs, it does so because it applies some physical or symbolic force). In this way, an entire series of metaphors of a physical kind (energy, work, potency)14 14 Respectively, for physics, the measures of an entity’s capacity to realize work, the transfer of energy from a body as it moves over a distance, and the ratio between the work realized and the time of its realization. acquires sociological feasibility through the possibility of observing this operator as something actually present (and with objective actancy) in social interactions.

John Dewey (1916DEWEY, John. Force and coercion. International Journal of Ethics, v. 26, n. 3, p. 359-367, 1916.; 1929(1916)) DEWEY, John. Force, violence and the Law. In: RATNER, Joseph (ed.) Characters and events. Popular essays in Social and Political Philosophy by John Dewey, v. II. New York: Henry Holt, 1929(1916), p. 636-641.also presents a series of physical metaphors to characterize violence, which he describes as “wasteful” (1916, p. 363). His treatment follows an energetic economy: the term power or energy “denotes the effective means of operation; ability or capacity to execute, to realize ends. (…) It means nothing but the sum of conditions available for bringing the desirable end into existence” (p. 361). With this, Dewey argues that power “is force” and that it is through the latter that “we excavate subways and build bridges and travel and manufacture; it is force which is utilized in spoken argument or published book” (p. 361). He continues: “(To say) not to depend upon and utilize force is simply to be without a foothold in the real world.” This energy/potential/power/force “becomes violence when it defeats or frustrates purpose instead or executing or realizing it” (p. 361). Although the thinker’s idea may appear to be a utilitarianist rationalism, it is effectively pragmatic insofar as it seeks to comprehend how the objective substrate of force is always an object of interpretation, such that when this energy is deviated from its ‘purpose,’ it seems excessive: more force than necessary to move/elastically deform a body (that is, to exceed the aforementioned optimal point) is a disproportionate force and merits the name violence if and when it is treated as an excess not associable to any purpose. Our approach is close to Dewey’s reasoning, but seeks to comprehend how the actors themselves qualify this allocation of energy: it is a question, therefore, of distinguishing between disproportion (a neutral phenomenon), purposelessness (an evaluation of pure effectiveness) and illegitimacy (an evaluation of valuative efficacy).

Force can be considered a model pragmatic entity insofar as, being fundamentally invisible, only its consequences are perceptible (Peirce, 1977PEIRCE, Charles S. Algumas consequências de quatro incapacidades. In: Semiótica. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1977(1893), p. 259-282.(1893)), that is, its effects on bodies. Thus, people seem to take into account the difference in its application (or the differential result of its relational applications): for social actors in practical life, force is, for all intents and purposes, the difference between forces in any interaction. Consequently, since what they generally see is this asymmetry (hence force is called disproportionate, considering the disproportion between applied and necessary force, the disequilibrium between force and counterforce), people evaluate it as excessive and may value or evaluate it according to moral perceptions linked to non-fixed points in energetic terms: apparently, for the actors, the same force applied in a situation and appearing as disproportional is judged violent or not depending on whether or not they perceive an energetic imbalance (that is, in the potential use of force) between those involved. As we shall see below, this violence may be subject to a moral problematization (and an attempt to intervene in the agency), depending on whether it is considered, at one pole, ‘unfair’ or ‘cowardly,’ or, at the other, ‘necessary’ or ‘natural,’ according to the situation, context, those involved and so on. In other words, it depends on the regime according to which this disproportionate force is qualified - as violence or not and, if so, what kind. In play here, therefore, is the name attributed actantially by people to this difference, based on the perception of an energetic economy that they consider active in the case at hand. A variable framework of energetic economies seems to be at work here, according to which the actors consider an investment of energy (and/or the capacity to invest it) and a return in terms of motion or deformation as the opposite poles of expression of what they perceive as a disproportionate force applied when certain movements or deformations take place.

In general, therefore, exploring the polysemy of violence through a sociology of disproportionate force involves focusing attention on three crucial aspects of the object: 1) how actors recognize the forces they believe to be constitutive of a particular situation; 2) the ways in which these actors respond to them; and 3) the forms through which they themselves produce and reproduce them.

Disproportionate force concentrates two dimensions essential to the analytic enterprise proposed here since it constitutes both a form of qualifying a particular situation and a form of recognizing the forces that compose it. Put otherwise, the recognition of something called violence simultaneously involves the recognition of a relation between forces - and, whether before or after, necessarily including their identification and characterization - and their moral qualification - as a relation subject to, after being called disproportionate, being called bad. By qualifying a particular situation or action as one of ‘violence,’ a certain configuration is also recognized, a plurality of actants organized in a specific way. In this sense, it can be said that violence, even taking into account its polysemy, is a profoundly relational category since it captures a particular configuration of forces and a plurality of actants at the very moment in which it is qualified as such. However, just as Simmel (2009SIMMEL, Georg. Sociology: inquiries into the construction of social forms. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2009(1908).(1908)) proposed, when it comes to thinking about the relations between form and content, these two dimensions are distinguishable only in analytic terms, since, for the actors themselves, they tend to appear as something integrated into a single experience. At any rate, the different ‘sociologies of violence’ analyzed here concern, first of all, the different forms of recognizing the forces that constitute a particular situation.

In this way, the protocol of a pragmatic sociology of violence, inaugurated as a sociology of the interpretation of disproportionate force, also inevitably entails a pragmatics of how this force is associated with its operators. Therefore, although it involves a force used in disproportion, at the same time it does not seem to be understood by the actors merely as difference, but also as something applied by some agents - figures described by them as strong (Misse, 1999MISSE, Michel. Malandros, marginais e vagabundos: a acumulação social da violência no Rio de Janeiro. 1999. PhD dissertation, IUPERJ, Rio de Janeiro, RJ.) or even as forces (Brodeur, 2004BRODEUR, Jean-Paul. Por uma sociologia da força pública: considerações sobre a força policial e militar. Caderno CRH, v. 17, n. 2, p. 481-489, 2004.; Bellaing, 2016BELLAING, Cédric M. de. Force publique: une sociologie de l’instituition policière. Paris: Economica, 2016.) - and therefore something idealized by people as contained in these agents. Moreover, this metonymy consists above all of a play of transferences, which, by superimposing actants and potencies, presumes a set of characteristics of the entities capable of mobilizing disproportional force, especially by situating them within the logic of so-called ‘urban violence’ (Machado da Silva, 1993MACHADO DA SILVA, Luiz Antônio. Violência urbana: representação de uma ordem social. In: NASCIMENTO, Elimar P.; BARREIRA, Irlys (eds.). Brasil urbano: cenário da ordem e da desordem. Rio de Janeiro: Notrya, 1993, p. 131-142.; 2004; Misse, 1999; Werneck, 2015WERNECK, Alexandre (ed.). Violências moduladas: gramáticas e dispositivos da crítica e da negociação na conflitualidade urbana no Rio de Janeiro. Research report, Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Faperj), 2015c.a; 2015c), its forms of sociability (Werneck; Talone, 2019TALONE, Vittorio da G. A memória actancial: as consequências de situações de ferimento, tensão e morte. In: CANTU, Rodrigo; LEAL, Sayonara; CORRÊA, Diogo S.; CHARTAIN, Laura (eds.). Sociologia, crítica e pragmatismo: diálogos entre França e Brasil. Campinas: Pontes, 2019, p. 387-412.) and its configurations. It so happens that the set of sociologies explored here is also a set of sociologies of this idealization insofar as it is imagined in violentized situations that someone applies force disproportionally to someone else.

The interpretative regimes of force and the sociologies of violentized worlds

As we have seen, while the sign violence serves to cover distinct things in the world, in the analyses of both researchers and everyday actors, it operates as a metonym, taking the form of diverse signs. We now emphasize the varied meanings of this signification, observed in the vast empirical matrix that we have examined, schematizing the meanings attributed to violence, which, in turn, enables us to map the metaphysics that provide the foundation for behaviors in situations where disproportionate force is mobilized.

A fundamental element of the mechanics of the social production of violence as a native concept involves a primary cognitive filter: through it, something that could be, in principle, pure, neutral, the mobilization of disproportionate force (an objective phenomenon) is taken and converted into a second sign, which actors recognize primordially as a disjunction in relation to the ideal. This cognitive filter is, therefore, strictly pragmatic, emphasizing the effectively practical character of the defined situations. When observed by actors in their day-to-day deployment, these situations translate into something that, with a minimum degree of discomfort (because these situations mobilize a large force), they generally call violence, although not necessarily expurgating it from the spectrum of definitions, either theirs or someone else’s, of what is plausible - as is generally the case in the aforementioned modern interdiction - and, notwithstanding this, without including it, conversely, in a process of moral positivization. In this way, it comprises a safe distance between ideal and factual, much as in the distinction proposed by Austin (1956-1957) between verbs and adverbs. In his analysis of the excuse - a linguistic device capable of giving an operative form of accountability (Scott; Lyman, 2008SCOTT, Marvin B.; LYMAN, Stanford M. Accounts. Dilemas: Revista de Estudos de Conflito e Controle Social, v. 1, n. 2, p. 139-172, 2008(1968).(1968)) to circumstances (Werneck, 2012WERNECK, Alexandre. A desculpa: as circunstâncias e a moral das relações sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2012a.a) - the author calls attention to the fact that the concept of adverb fundamentally presumes an alteration vis-à-vis the ideal version of an action, represented by the verb in the infinitive (Austin, 1956-1957, p. 13)AUSTIN, John L. A plea for excuses: the presidential address. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, New Series, v. 57, p. 1-30, 1956-1957.:

(I)t is interesting to find that a high percentage of the terms connected with excuses prove to be adverbs, a type of word which has not enjoyed so large a share of the philosophical limelight as the noun, substantive or adjective, and the verb: this is natural because, as was said, the tenor of so many excuses is that I did it but only in a way, not just flatly like that - i.e., the verb needs modifying.

This distancing from the ideal through adverbialization is included in the spectrum of the viable: the adverb functions as an envisaged or predictable modality of the unfolding of an action without it being either the perfect mirror of its idealized version or its imperfect demonization. Thus, for example, if the infinitive of the verb ‘walk’ expresses an image of how the category functions ideally, how one walks for anyone who understands what walking is (putting one foot in front of the other, going from one point in space to another, and so on), an adverb - like ‘slowly,’ ‘quickly’ or ‘stumblingly’ - creates different versions of this abstract movement and litters its path with stones. But none of these obstacles will hurl the walker into the limbo of uncertainty: he or she knows what slow is, what quick is, what stumbling is. This model, which will serve later as a basis for what we call - inspired by Corrêa (2017CORRÊA, Diogo. Comments to the theory workgroup. In: 41º Anpocs Annual Congress. Caxambu, MG, 2017.) - an adverbial approach to violence, accounts for a pragmatic evaluation by expressing the perception of a dissimilar to the ideal, perceived by the actors precisely as dissimilar, but at the same time recognized by them as a modality of this ideal rather than a rupture with it. As Neitzel and Welzer write (2014NEITZEL, Sönke; WELZER, Harald. Soldados: sobre lutar, matar e morrer. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2014., p. 409), “violence is practiced by all groups (…) if cultural and social situations make it seem sensible.” In this field can be included not only those situations in which using force disproportionally attributes a productive purpose (according to the actors) to destruction (like knocking down a wall to build another), but also the ‘tough’ tackle or the fight between supporters in sports, the spider that eats the fly, the punishment between gang members in the world of crime, or even the lynching of supposed criminals in the interpretation of the lynchers and their supporters.15 15 For a valuable description of the praxeology of lynching, see Rodrigues (2012).

This classification as violence without seeking to annul the agency of the deployer of the force can be passed through a second, more properly moral filter, which can requalify the disproportionate force in terms of value. This disproportion may be described as morally positive, a qualification historically dominated by the treatment as coercion, and be more than neutralized, becoming positivized in the form of a legitimate use of force - the “legitimate violence” monopolized by the State described by Weber (1947WEBER, Max. The theory of social and economic organization. Glencoe (USA): The Free Press, 1947(1922).(1922)). Alternatively, it may be morally negativized and reduced to what, for the natives, turns into the substrate of a sociology ‘of violence’ - what they more commonly call violence: the action of disproportionate use of force that they do not recognize, nor see as applicable, with an acceptable meaning. The action is thus classified as ‘violent’ in a form according to which it falls to the level of the unacceptable. In the first case, the process of effectuation involves justification (Boltanski; Thévenot, 2020BOLTANSKI, Luc; THÉVENOT, Laurent. A justificação: sobre as economias da grandeza. Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ, 2020(1991).(1991)), the allocation on a regime of justice (Boltanski, 1990) or regime of the just (Thévenot, 2006THÉVENOT, Laurent. L’action au pluriel: Sociologie des régimes d’engagement. Paris: Découverte , 2006.), constituting the basis of an order of legitimate domination (Weber, 1999(1921)WEBER, Max. Economia e sociedade, v. 2. Brasília, Editora UnB, 1999(1921).). In the second case, actions are effectuated either through a circumstance of the situation or through pure and simple imposition (Werneck, 2012WERNECK, Alexandre. A desculpa: as circunstâncias e a moral das relações sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2012a.a).

This negative moralization can take some different paths. One of them is that the operation of negativization shifts from the specific qualification of a case (person, object, institution, action, and so on) to a generalized level, becoming a metaphysics, a social representation. Another is, through an operation of - for its practitioners - revelation or unveiling, to treat these operations of qualification, metalinguistically, as themselves kinds of violence, altering the positions of qualifier-qualified (or, in many interpretations, inverting the victim-persecutor polarization) and redesigning the operation of the use of force as something previously presented in ineffective or even deceitful form.

This matrix of diverse possibilities results in different meanings that can be analytically conferred by examining the idea of violence, enabling different regimes of interpretation or analytic representation of violence to be discerned, depending on which dimension or operation of this gallery and its repercussions is emphasized, and on which social actors violentized worlds operate, depending on how the signifier (i.e., that which determines the representation/symbolization of something) violence is morphologically localized.

Before presenting these frameworks, however, we need to explain in more detail what precisely we mean when we describe these ‘worlds’ as ‘regimes.’ A regime is a grammar. As two of us wrote in another text (Werneck; Talone, 2019WERNECK, Alexandre; TALONE, Vittorio da G. A ‘sociabilidade violenta’ como interpretante efetivador de ações de força: uma sugestão de encaminhamento pragmático para a hipótese de Machado da Silva. Dilemas: Revista de Estudos de Conflito e Controle Social, v. 12, n. 1, 2019, p. 24-61., p. 36):

(The) meaning of the term grammar in the pragmatic sociology of critique (which guides us here) is specific. Inspired by the generative linguistics of Noam Chomsky (1965CHOMSKY, Noam. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge (USA): The MIT Press, 1965.),16 16 Lemieux (2018, p. 58) argues that the pragmatic concept of grammar differs from Chomsky’s generative model. We disagree. The author concentrates his distinction in the more etiological/naturalist aspect of the linguist’s approach, whereby the learner of languages possesses an innate biological foundation and performance should not be taken as a measure of linguistic efficacy - although he does not make explicit the divergence with how Bourdieu (2000(1972)) appropriates the term to develop his ‘generative structuralism.’ It so happens that the pragmatic description of grammar is founded precisely on the concept of competence, central to Chomsky, and since it does not comprise a theory of the origins of the apprehensions of competences, but of their operativity, it also benefits precisely from generativity, the flexible/creative character of the practical exercise of grammatical metaphysics. it corresponds to a behavioral modeling whose basis is a competence, that is, the resourceful use of ideally established but not entirely obligatory patterns of actuation. Boltanski and Thévenot (2020BOLTANSKI, Luc; THÉVENOT, Laurent. A justificação: sobre as economias da grandeza. Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ, 2020(1991).(1991), p. 258) define competence as “a capacity to recognize the nature of a situation and put into action the principle (…) to which it corresponds.” Werneck (2015WERNECK, Alexandre (ed.). Violências moduladas: gramáticas e dispositivos da crítica e da negociação na conflitualidade urbana no Rio de Janeiro. Research report, Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Faperj), 2015c.(b), p. 193), for his part, proposes an alternative definition (though coordinated with the former), actantial in inspiration: “A trait demonstrated in situational actions, indicating its localization within a specific moral actantial grammar, as a measure of resourcefulness in rules that verify criteria of concretization of the situation-action, that is, it consists of the criterion sought in situation-actions when it is verified whether or not they can be effectuated.” In other words, competence is also the value in play in the evaluation made by actors when they scrutinize a social phenomenon to effectuate its occurrence. In this kind of grammar, actors are impelled to act creatively through established patterns in order to act within the terms of these patterns, as close as possible to their ideality, but in more effective form for the ultimate purpose of any grammar, which is to mutually adjust the various behaviors, enabling their communication (that is, their common placement). Formally, in the economies of worth approach (Boltanski; Thévenot, 2020(1991)), a regime is, therefore, a grammar - a grammar with the specific purpose of regulating the moral scrutinization that effectuate social phenomenon. It thus comprises a valuative/evaluative apparatus whose basis is a parameter called competence.

When we talk of regimes of analytic representation of violence, therefore, we are dealing with grammars whose competences effectuate in a specific way the phenomenon of qualifying mobilizations of disproportionate force as violence. Consequently, since attributing meaning to disproportionate force is the object of the discussion on ‘violence,’ its resignifications could, based on our empirical research, be mapped onto a typology of ‘sociologies,’ distributed in the following sets of regimes, depending on the grammatical type occupied by the signifier ‘violence’:

-

1) Regimes in which ‘violence’ is a term understood as a substantive, that is, in which this object is understood to constitute a substance and, therefore, an effectively objective entity and a phenomenon in itself that needs to be explained, giving shape to three sociologies:

-

A political sociology of violence: in this case, interpretation focuses on the role performed by coercion (which becomes an alternative name for the use of disproportionate force) in social cohesion, in the consolidation of social relations (notably those of legitimate domination) and in the civilizing process.17 17 For a general description of models of the role of coercion in the modern social order, see Elias (1990(1939); 1993(1939)) and Bendix (1996). In this kind of reading, the analysis focuses on the question of order, and the fundamental question becomes: what coercive practices are capable of guaranteeing social order, how do they function, and how productive are they (i.e., what are their results in terms of ordering)?18 18 The academic approach of Zaluar (1985; 1994; 2004; 2014) appears to set out from an interconnection between substantivist and praxiological sociologies and this political strand, insofar as it valorizes the tension between a ‘warrior ethos’ and a containment of the drives (originally proposed by Norbert Elias) as an etiology of urban violence.

-

A (substantivist) sociology ‘of violence’: here the aim is to produce an etiology - i.e., in question are the causes - of the recourse to disproportionate force in situations in which it is hegemonically considered unacceptable. The fundamental question, therefore, is: why do social actors immersed in a peaceful sociability resort to disproportionate force? In this approach, the concept of violence is a central metonymic operator since, in practice, it, in more determinant form than in any of the other sociologies presented here, refers to those other two phenomena, social conflict (when involving the use of unequal force) and, through a legal divide (criminalization),19 19 For an analysis of how this process is constituted by the mechanics of crimination and incrimination, see Misse (1999). crime - such that the question posed by this sociology of violence ultimately concerns an etiology of these two types of occurrences.

-

A critical sociology of violence: here both the moral positivization of its qualification as coercion and the moral intensification of its negativization as unacceptable violence are analyzed from the viewpoint of the role they perform in the process of domination, making explicit - or, for the critical analyst, revealing - the interests involved in each of the operations. In the first case, it passes from coercion to government practice, while legitimate violence becomes read as legitimized violence, exposing and underlining the procedural, unnatural, and imposing character of this operation. In the other case, it passes from violence (conflict and crime) to resistance to an unequal order. In both configurations, an inversion occurs in the moral sign attributed previously, and the emphasis is placed on characterizing and explaining another violence, taken as the true kind (that is, to be seen as problematic and interdicted), the violence of power. From the viewpoint of academic analyses, this interpretation is usually pursued by Marxist, Foucauldian, Bordieuan, feminist, or post-colonialist approaches.20 20 For the unification of these approaches as ‘critiques,’ see Burawoy (2004) and, in pragmatic terms, Bénatouïl (1999) and Boltanski (2009, pp. 15-32). A demonstration of the presence of an idea of violence in each of these authors would exceed the limits of this text, but can be found, for instance, in Horowitz (1962).

-

2) A regime in which ‘violence’ is understood as an adjective, that is, in which this sign is understood to constitute an attribute, associable with substances in themselves neutral, implying:

-

A constructivist sociology of violence focused on attribution: in this regime (constructivism reappears in another form later), analysis centers on the process of attributing the attribute of ‘violent’ - which does not define a substance, therefore, but rather situated characteristics identified in actions/actors. Here the fundamental question is: how does an attribute becomes associated with an action or an entity, whether individual, collective, or categorial? The heterogeneous ‘constructivist’ approaches avoid attempts to explain an objective reality, emphasizing instead that reality is built and to some extent contingent on the observer’s viewpoint. It is the subject of knowledge who generates his or her representation of the object and conjectures about the functioning of reality, built and tested through predictions of what will take place. From the viewpoint of academic analyses, it comprises the founding characteristic of approaches like that of labeling - as in Becker (2008BECKER, Howard S. Outsiders: estudos de sociologia do desvio. Rio de Janeiro, Jorge Zahar. (2008(1963)).(1963)) and Goffman (1986GOFFMAN, Erving. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Touchstone, 1986(1963).(1963))21 21 For a description and history of the approach, especially one showing the influence of philosophical pragmatism for its founders, see Werneck (2014a). - and subjection - as in Misse (1999MISSE, Michel. Malandros, marginais e vagabundos: a acumulação social da violência no Rio de Janeiro. 1999. PhD dissertation, IUPERJ, Rio de Janeiro, RJ., 2008, 2010MISSE, Michel. Crime, sujeito e sujeição criminal: aspectos de uma contribuição analítica sobre a categoria bandido. Lua Nova: Revista de Cultura e Política, n. 79, p. 15-38, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-64452010000100003

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-6445201000... , 2018MISSE, Michel. Violence, criminal subjection and political merchandise in Brazil: an overview from Rio. International Journal of Criminology and Sociology, n. 7, p. 135-148, 2018., 2019MISSE, Michel. The puzzle of social accumulation of violence in Brazil: some remarks. Journal of Illicit Economies and Development, v. 1, n. 2, p. 60-65, 2019.) and Teixeira (2011TEIXEIRA, Cesar P. A construção social do ‘ex-bandido’: um estudo sobre sujeição criminal e pentecostalismo. Rio de Janeiro: 7Letras , 2011b.b, 2012MISSE, Michel; WERNECK, Alexandre. O interesse no conflito. In: MISSE, Michel; WERNECK, Alexandre (eds.). Conflitos de (grande) interesse: estudos sobre crimes, violências e outras disputas conflituosas. Rio de Janeiro: Garamond, 2012, p. 7-25., 2013). -

3) A regime in which the idea of ‘violence’ is understood as an adverb - as cited earlier, drawing inspiration from Corrêa (2017CORRÊA, Diogo. Comments to the theory workgroup. In: 41º Anpocs Annual Congress. Caxambu, MG, 2017.) - i.e., a regime in which the object is understood to constitute a modality or circumstance in the exercise of actions, from which derives:

-

A praxeological sociology of violence: here analysis focuses on the practices of - and their routinization by - social actors, taking seriously how they themselves, or others who speak about them, comprise violence as a resource in their lives. Here the fundamental question is: how does violence participate in the lives of persons in a normal way?22 22 An especially strong example of this kind of approach in academic sociologies is found in what the authors tend to call “ethnographies of crime.” For a recent survey of this genre in Brazil, see Aquino & Hirata (2018), and for a discussion of how these works address violence, see Grillo (2019).

-

4) A regime in which the term ‘violence’ is understood as metaphysics - i.e., in which the object, whether something objective in the world or not, is understood to function as an intersubjective abstraction:

-

A constructivist sociology of violence focused on representation: here the analysis concentrates on the process and/or the mechanics of generalization of the attribute of violence as an interpretative framework/filter for a large number of social actors - for instance, in a same society or within a same space of communion of meanings, they share the same “blocks of meaning” concerning violence (Porto, 2006PORTO, Maria Stela G. Crenças, valores e representações sociais da violência. Sociologias, v. 8, n. 16, p. 250-273, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-45222006000200010

https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-4522200600... ). Again, violence is not conceived as a phenomenon in itself, something substantial and objective in the world, but rather as a social representation, as suggested, in the context of academic analyses, by authors such as Michel Misse (1999MISSE, Michel. Malandros, marginais e vagabundos: a acumulação social da violência no Rio de Janeiro. 1999. PhD dissertation, IUPERJ, Rio de Janeiro, RJ.), Maria Stela Grossi Porto (1999PORTO, Maria Stela G. A violência urbana e suas representações sociais: o caso do Distrito Federal. São Paulo em Perspectiva, v. 13, n. 4, p. 130-135, 1999., 2006PORTO, Maria Stela G. Crenças, valores e representações sociais da violência. Sociologias, v. 8, n. 16, p. 250-273, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-45222006000200010

https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-4522200600... ), and Luiz Antônio Machado da Silva (1993MACHADO DA SILVA, Luiz Antônio. Violência urbana: representação de uma ordem social. In: NASCIMENTO, Elimar P.; BARREIRA, Irlys (eds.). Brasil urbano: cenário da ordem e da desordem. Rio de Janeiro: Notrya, 1993, p. 131-142.), each in his or her distinct way. Consequently, setting out from the notion of representation, we return to the notion of frameworks of signification: people express worldviews in which they try to explain and render meaningful the situations that they live through - such projections are found in the mind of real persons and serve to guide their actions (Weber, 1947WEBER, Max. The theory of social and economic organization. Glencoe (USA): The Free Press, 1947(1922).(1922)). Here, then, representation is converted into a moral metaphysics, a valuative frame of reference capable of evaluating and, in so doing, guiding actions. The idea of an order based on force (in this case, physical), a world (Boltanski; Thévenot, 2020BOLTANSKI, Luc; THÉVENOT, Laurent. A justificação: sobre as economias da grandeza. Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ, 2020(1991).(1991)), can be understood as a metaphysics in the sense of an abstraction about life effectuated by social actors, which serves as an abstract horizon to sustain their actions and their concrete and situated definitions of situations (Thomas, 1969THOMAS, William I. The unadjusted girl: with cases and standpoint for behaviour analysis. Monclair (USA): Patterson Smith, 1969(1923).(1923)).

Figure 1 below summarizes the matrix of regimes of analytic qualification of violence.

As we stated at the outset of this text, this framework of sociologies should not be taken as a synthesis of the main approaches and/or theories on violence in vogue in the social sciences, nor should it be thought that the different regimes describe different established theories or approaches. In fact, many of these tend to be constituted by composites of two or more of these regimes, which ultimately represented a semiotics of the analytics of violence. Moreover, from the viewpoint of several of these regimes, some of the others can be read as particular cases of their representation.23 23 An example can be found in the work of one of the authors (Teixeira, 2012), which describes models of native representation of the causes of the ‘embedding’ of crime in individuals as the bases of techniques of ‘treatment’ by different agents. In this case, a constructivist reading is undertaken of the actual substantivist reading. Thus, here we have attempted neither to explore how this framework is mirrored in the panorama of studies on crime and violence in Brazil and the world nor to confirm it through a bibliographic review. The objective here has been to test a more abstract treatment of forms of understanding the term/sign violence through a semiotics of its valences (Livet; Thévenot, 1997LIVET, Pierre; THÉVENOT, Laurent. Modes d’action collective et construction éthique: les émotions dans l’évaluation. In: DUPUY, Jean-Pierre; LIVET, Pierre (eds.). Coloque de Cerisy: les limites de la racionalité, tome 1. Rationalité éthique et cognition. Paris: Découverte , 1997, p. 412-439.), both native and analytical.

Final considerations: violence as an interpretant and a pragmatic sociology of morality

One of the most striking - and, for our present analysis, most relevant - characteristics of the so-called pragmatic sociology of critique (Boltanski, 2009BOLTANSKI, Luc. De la critique: précis de sociologie de l’émancipation. Paris: Gallimard, 2009.) - which features among the most prolific contemporary approaches of a pragmatist orientation (Werneck, 2016WERNECK, Alexandre. A força das circunstâncias: sobre a metapragmática das situações. In: VANDENBERGHE, Frédéric; VÉRAN, Jean-François (eds.). Além do habitus: teoria social pós-bourdieusiana. Rio de Janeiro: 7Letras , 2016, p. 155-192.) - is that one of its fundamental wings, the economies of worth (EW) model (Boltanski; Thévenot, 2020(1991)), presents the metaphysical-pragmatic pairing, taken here as foundational, as a mirroring between two social orders (polity and world) ultimately revealed to be two metaphysics, constructed around the idea of an achieved utopia (Boltanski, 1990, p. 150-151):

(T)hese old Utopian constructions, aiming at an inaccessible ideal, have nothing to do with the people of today’s world, who for the most part have never opened a book by Hobbes or Saint-Simon or Rousseau, and could care less? I maintain that the terms ‘utopia’ or ‘ideal,’ as opposed to ‘reality,’ are the pivots of the critique. They cannot be set aside without examination, for Utopias do exist. It is possible to construct imaginary worlds that offer at least some degree of systematicity and coherence. (…) I must be in a position to establish the difference not only between impossible and achievable Utopias but also between achievable and achieved Utopias. For this, an objective indicator is available. A Utopia is achieved, and thus deserves the name of polity, when the society in question encompasses a world of objects that make it possible to set up tests that rely on a particular principle of equivalence, the one whose logical possibility is deployed in this Utopia.

The idea of polity (cité) - in the EW model, an achieved utopia founded on the idea of justice, subsequently developed by the authors into a detailed analysis of justifications and agreements24 24 For a summary, see Boltanski & Thévenot (1999). The complete model is presented in Boltanski & Thévenot (2020(1991)). An explanatory presentation of the model is made in Werneck (2012a, pp. 81-99) - appears here as one of diverse possible imagined metaphysics (albeit rooted in experience, without supernatural fantasies), ideal from the viewpoint of their projections of the good onto social life. For its part, the idea of world, which grounds the concept proposed in the excerpt cited (and its attribution to a polity), involves an abstraction emphatically founded in practical life, since it is formed mainly by assemblages of objects put together by actors - but even so, consists of an abstraction. The two mirror each other, one as an elevated abstraction and the other as a grounded abstraction, in the same way as a political philosophy and a sociological theory: the first as an idealization of a thinker who, singularly knowledgeable about the world, projects how it should be; the second as a description of a researcher who, as an empirical observer of the world, explains in generalizable terms what it actually is.

This discussion on the operativity of an analytic treatment based on multiple metaphysically oriented worlds has had a productive impact on our own work. Talone (2015TALONE, Vittorio da G. O ‘quadro da perturbação’: a rota de conflitos nos trajetos de ônibus do Rio de Janeiro. Cadernos de Estudos Sociais e Políticos, v. 4, n. 8, p. 87-108, 2015b.a) suggests that the same form of construction is applicable to social actors when they construct dystopias, imagining models of social life (notably through the idea of a violent city), orderings of sociability, also founded on idealities (how people imagine the world to function) and that call for a pragmatically founded abstraction (a world) to sustain them, but which in this case are not founded on the good but on a view of social life as degenerate, disordered, bad. The idea of an achieved dystopia (Talone, 2015a) thus allows us to consider how social actors conceive the world by thinking of its worst possible version in order to move about in social life and how they define situations on this basis. Teixeira (2013TEIXEIRA, Cesar P. A teia do bandido: um estudo sociológico sobre bandidos, policiais, evangélicos e agentes sociais. 2013. PhD dissertation, PPGSA, UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro,RJ.; 2016TEIXEIRA, Cesar P. O testemunho e a produção de valor moral: observações etnográficas sobre um centro de recuperação evangélico. Religião & Sociedade, v. 36, n. 2, p. 107-134, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-85872016v36n2cap06

https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-85872016v36...

), for his part, has worked with the circumscription of complex social worlds around the idea of a world of crime and how its central figures are conceived (Teixeira, 2015; Freire; Teixeira, 2016FREIRE, Jussara; TEIXEIRA, Cesar P. Humanidade disputada: sobre as (des)qualificações dos seres no contexto de ‘violência urbana’ do Rio de Janeiro. Terceiro Milênio: Revista Crítica de Sociologia e Política, v. 6, n. 1, p. 58-85, 2016.; 2019). In his work, different native theories about how crime becomes embedded in the person define actual practical operative worlds, each one according to a specific logic. Also along these lines, Werneck (2012WERNECK, Alexandre. A contribuição de uma abordagem pragmatista da moral para a sociologia do conflito. In: MISSE, Michel; WERNECK, Alexandre (eds.). Conflitos de (grande) interesse: estudos sobre crimes, violências e outras disputas conflituosas. Rio de Janeiro: Garamond, p. 337-354, 2012b.a; 2015bWERNECK, Alexandre. Dar uma zoada, botar a maior marra: dispositivos morais de jocosidade como formas de efetivação em situações de crítica. Dados: Revista de Ciências Sociais, v. 58, n. 1, p. 221-287, 2015b. https://doi.org/10.1590/00115258201542

https://doi.org/10.1590/00115258201542...

; 2016WERNECK, Alexandre. A força das circunstâncias: sobre a metapragmática das situações. In: VANDENBERGHE, Frédéric; VÉRAN, Jean-François (eds.). Além do habitus: teoria social pós-bourdieusiana. Rio de Janeiro: 7Letras , 2016, p. 155-192.; 2019aWERNECK, Alexandre. Política e ridicularização: uma sociologia pragmática da ‘graça’ da crítica em cartazes das ‘Jornadas de Junho’. Interseções: Revista de Estudos Interdisciplinares, v. 21, n. 3, p. 611-653, 2019a. https://doi.org/10.12957/irei.2019.47254

https://doi.org/10.12957/irei.2019.47254...

; 2019b; Werneck; Loretti, 2018WERNECK, Alexandre; LORETTI, Pricila. Critique-form, forms of critique: the different dimensions of the discourse of discontent. Sociologia & Antropologia, v. 8, n. 3, p. 973-1008, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1590/2238-38752018v839

https://doi.org/10.1590/2238-38752018v83...

) has demonstrated in various studies how actors resort to a metapragmatic dimension (i.e., to circumstances) to disassemble the universality of metaphysical ideals in favor of a descriptive correction of the worlds actually presented to them. The same author has also shown how the representation of urban violence can be conceived as an actantial system, operated in terms of the effectiveness of critical actants of this scenario, each defined according to a form of managing force (Werneck, 2015a, 2019b). Set in dialogue here, our different perspectives allow us to take seriously the process through which social actors operate interpretative social worlds that are founded, according to their own constructions, on disproportionate, violentized force, defining social situations via this framework.

The observation of the diverse regimes of violentization in the preceding items of this text has made explicit the plurality of forms through which social actors, in their technical or native analyses, account for the effectuation of occurrences in practical life - and, consequently, recognize practical worlds corresponding to it - based on metaphysics founded on disparate ideas of what something cognizable as violence (disproportionate force when interpreted through one of the regimes) is or should be used. This allowed the design of a research agenda to explore in more depth the peculiarities of each of these grammars and elaborate an analytic protocol for this purpose: by mapping the different meanings of the sign ‘violence’ in each grammar, we can trace out a framework of different competences deployed to find diverse worlds (one utopian, four dystopian, one neutral, always from the viewpoint of the actors involved), all of them articulated at different levels. Table 1 summarizes the interpretation.

While the approach has proven well-suited to this task of mapping violence grammatical diversity, the contiguous observation of the items of this variation also allows us to discern something about their unity that only separation made perceptible. The transversal observation of this framework in the form of a pragmatics of these various analytical representations clearly revealed the same phenomenon traversing them: qualification. It is in the actors’ intersubjective attempt to produce a definition to designate a broad and varying continuum of actions, situations, and actors under a sign called violence - whether this involves naming, adjectivizing, generalizing or identifying the modality - that we encounter the phenomenology we wish to highlight here. Moreover, this attempt to qualify needs to be understood, like any other of this kind, as an intersubjective production of meaning (Weber, 1947WEBER, Max. The theory of social and economic organization. Glencoe (USA): The Free Press, 1947(1922).(1922); Boltanski; Thévenot, 1983BOLTANSKI, Luc; THÉVENOT, Laurent. Finding one’s way in social space: a study based on games. Social Science Information, v. 22, n. 4-5, 1983, p. 631-680. ), which signifies the establishment of a shared foundation and thus of a socially processed and scrutinized definition (Peirce, 1992PEIRCE, Charles S. How to make our ideas clear. In: The Essential Peirce, v. 1: Selected Philosophical Writings‚ (1867-1893). Bloomington (USA): Indiana University Press, 1992(1878), p. 124-141.(1878); Weber, 2001(1904)WEBER, Max. A ‘objetividade’ do conhecimento na ciência social e na ciência política. In: Metodologia das ciências sociais. São Paulo: Cortez, 2001(1904), p. 107-154.).

However, it is not simply a matter of recognizing in a constructivist way the constructed character of the sign - this already occurs as a principle of semiotics itself. Instead, it is a question of going further and comprehending the principles regulating its conditions of possibility and the valuative logics underlying its various moralities. It is precisely a question, therefore, of analyzing the metalanguage shaping these regimes as such, the laws of assemblage involved in a model of effectuation of violence as a grounding metaphysics, comprehending how the actors adopt different readings of violence as value (which, in table 1, appears in the column Worth in Play). Consequently, the question here is the analysis of the conditions of possibility of two hemispheres of a pair, both of which lay claim to being foundational, sometimes eclipsing the role of the other. However, like in any semiotic process, we understand this semiotic instauration as a pair of parallel and inseparable endeavors: metaphysics and pragmatics are mutually determined and created contiguously; neither can one say that a world of devices (Peeters; Charlier, 1999PEETERS, Hugues; CHARLIER, Philippe. Contributions à une théorie du dispositif. Hermés, n. 25, p. 15-23, 1999.) only takes shape thanks to the intervention of a metaphysics (as her egg), nor can one sustain that a grounding metaphysics comes to exist through elevation to the abstract plane of concrete objects and their situated mobilizations (as their chicken). Quite otherwise, it comprises a process that, perceived situationally, is specified precisely by being configured in a situation.25 25 Obviously, this does not mean no history/genealogy can be made of the metaphysics established/fixed/consolidated in the social/cultural repertoire, nor any typical situations regularly recognized by actors as recurrent tools of social life. On the contrary, as Wright Mills (1940) proposes, these recurrences seem to be the rule of how actors operate this semiotics, seeking to navigate within the consolidated repertoires rather than becoming involved in creative undertakings. Thus, the analysis focuses on the mapping of the forms through which this occurs at specific moments.

As a consequence, a pragmatic sociology of violence extends across a spectrum that spans from the history/genealogy of the processes of grammatical abstraction/establishment (and bearing the very fabric of their particular process of effectuation) to the apprehension, characterization, and mapping of regimes of violentization - i.e., grammars, especially (this seems to be the principal vocation of this approach) those involving the analysis of the specific form through which the sign violence appears (sometimes as a polysemic signifier, sometimes as content, sometimes as both) in the phenomenon defining a situation/effectuation. It is in this sense that ‘violence’ becomes understood as the link of a metaphysical-pragmatic pairing - transformed into an interpretant - and the question of this sociology becomes, in a broad sense, the diverse forms of effectuation.