Abstract

This study identifies the food habits of the margay, Leopardus wiedii (Schinz, 1821), and the jaguarundi, Puma yagouaroundi (É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilare, 1803), in the Vale do Rio Doce Natural Reserve and in the Sooretama Biological Reserve, Espírito Santo, Brazil. We determined the diet of both species by the analysis of scats. Fecal samples were collected from April 1995 to September 2000 and identified based on the presence of hairs that were ingested during self-grooming. Scats were oven-dried and washed on a sieve, and the screened material was identified using a reference collection. Of the 59 fecal samples examined, 30 were confirmed to be from the margay and nine of them from the jaguarundi. Mammals were the most consumed items in the diet of the margay, occurring in 77% of the fecal samples, followed by birds (53%) and reptiles (20%). Among the mammals consumed, marsupials (Didelphimorphia) were the most common item (66%). In the diet of the jaguarundi, birds were the most consumed items and occurred in 55% of the fecal samples; mammals and reptiles occurred in 41% and in 17% of the fecal samples, respectively. From this work we conclude that the margay and jaguarundi fed mainly upon small vertebrates in the Vale do Rio Doce Natural Reserve and in the Sooretama Biological Reserve. Although sample sizes are therefore insufficient for quantitative comparisons, margays prey more frequently upon arboricolous mammals than jaguarundis, which in turn prey more frequently upon birds and reptiles than margays. This seems to reflect a larger pattern throughout their geographic range

Carnivores; food habits; mesopredators; small felids

SHORT COMMUNICATION

Diet of margay, Leopardus wiedii, and jaguarundi, Puma yagouaroundi, (Carnivora: Felidae) in Atlantic Rainforest, Brazil

Rita de Cassia BianchiI,III,* * Corresponding author. Laboratório de Vida Selvagem, Embrapa Pantanal. Rua 21 de setembro 1880, 79320-900 Corumbá, MS, Brazil. E-mail: rc_bianchi@yahoo.com.br; ritacbianchi@gmail.com Editorial responsibility: Fernando de C. Passos ; Aline F. RosaII; Andressa GattiII; Sérgio L. MendesI

IPrograma de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo. 29075-910 Vitória, ES, Brazil

IIEscola de Ensino Superior São Francisco de Assis. 29650-000 Santa Teresa, ES, Brazil

IIILaboratório de Vida Selvagem, Embrapa Pantanal. Rua 21 de setembro 1880, 79320-900 Corumbá, MS, Brazil. E-mail: rc_bianchi@yahoo.com.br; ritacbianchi@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This study identifies the food habits of the margay, Leopardus wiedii (Schinz, 1821), and the jaguarundi, Puma yagouaroundi (É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilare, 1803), in the Vale do Rio Doce Natural Reserve and in the Sooretama Biological Reserve, Espírito Santo, Brazil. We determined the diet of both species by the analysis of scats. Fecal samples were collected from April 1995 to September 2000 and identified based on the presence of hairs that were ingested during self-grooming. Scats were oven-dried and washed on a sieve, and the screened material was identified using a reference collection. Of the 59 fecal samples examined, 30 were confirmed to be from the margay and nine of them from the jaguarundi. Mammals were the most consumed items in the diet of the margay, occurring in 77% of the fecal samples, followed by birds (53%) and reptiles (20%). Among the mammals consumed, marsupials (Didelphimorphia) were the most common item (66%). In the diet of the jaguarundi, birds were the most consumed items and occurred in 55% of the fecal samples; mammals and reptiles occurred in 41% and in 17% of the fecal samples, respectively. From this work we conclude that the margay and jaguarundi fed mainly upon small vertebrates in the Vale do Rio Doce Natural Reserve and in the Sooretama Biological Reserve. Although sample sizes are therefore insufficient for quantitative comparisons, margays prey more frequently upon arboricolous mammals than jaguarundis, which in turn prey more frequently upon birds and reptiles than margays. This seems to reflect a larger pattern throughout their geographic range.

Key words: Carnivores; food habits; mesopredators; small felids.

Many studies indicate that some predators have the potential to strongly structure communities (TERBORGH 1992, TERBORGH et al. 1999). However, these predators represent large top carnivores in relatively simple systems, and most carnivores are neither large nor apex predators. The ecological role of mesocarnivores (mid-sized carnivores) in structuring communities is especially relevant in the context of terrestrial ecosystems conservation (TERBORGH et al. 2001, GITTLEMAN & GOMPPER 2005). The importance of small and mid-sized carnivores can be assessed at two levels: the role assumed by these predators when they are de facto top carnivores and the importance of these predators within communities that also contain large top carnivores. Because carnivore communities are strongly influenced by intraguild predation and competition, the loss of a top predator may result in a rise and fall of some secondary and tertiary carnivores, respectively. The consequences of these interactions, which fundamentally involve a body-size-based shift in trophic status of mesocarnivores from formerly secondary or tertiary predator to apex predador, can be seen throughout the food web and in fundamental measures of biodiversity (CROOKS & SOULÉ 1999). Mesocarnivores make up the majority of the species in the order Carnivora, but our understanding of their ecology is superficial (GITTLEMAN & GOMPPER 2005).

The margay, Leopardus wiedii (Schinz, 1821), and the jaguarundi, Puma yagouaroundi (É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilare, 1803), are mid-sized carnivores with broad distribution in the Neotropics and are found in a variety of habitats (OLIVEIRA 1998b, SUNQUIST & SUNQUIST 2002). These two, together with two other felids, the ocelot, Leopardus pardalis (Linnaeus, 1758) and the oncilla, Leopardus tigrinus (Schreber, 1775), make up the community of meso-cats of the Atlantic Rainforest.

The margay is distributed from southern Texas, United States, to northern Uruguay and Argentina and can be more strongly associated with forest habitats (both evergreen and deciduous) than any other tropical American cats (OLIVEIRA 1998b, SUNQUIST & SUNQUIST 2002). The diet of the margay consists primarily of arboreal mammals (BEEBE 1925, KONECNY 1989, AZEVEDO 1996) but MONDOLFI (1986) found a higher frequency of terrestrial mammals.

The jaguarundi is distributed from southern Texas, United States, through the inter-Andean valley of Peru, to southern Brazil and Paraguay, to the provinces of Buenos Aires and Rio Negro in Argentina (OLIVEIRA 1994, OLIVEIRA 1998a). The jaguarundi has been reported from several habitats, such as tropical rainforests, tropical and subtropical forests and shrub savannas (OLIVEIRA 1994, 1998a).

The diet of the jaguarundi consists mainly of small rodents, birds, and reptiles. In Belize, mammals were the most important item, and the cotton rat, Sigmodon hispidus Say & Ord, 1825, was the most frequently found species in scats, followed by small birds (KONECNY 1989). In Venezuela and southeast of Brazil, lizards, birds and rodents were the most common items found in scats of the jaguarundi (BISBAL 1986, MONDOLFI 1986, MANZANI & MONTEIRO-FILHO 1989). This cat has also been observed preying on a characid fish trapped in a temporary pond (MANZANI & MONTEIRO-FILHO 1989).

The diet description of many small felids remains largely unknown. The aim of this study was to identify the food habits of the margay and the jaguarundi in the Vale do Rio Doce Natural Reserve and in the Sooretama Biological Reserve, in northern Espírito Santo state (19º03'S and 40º05'W).

The Vale do Rio Doce Natural Reserve (VRDNR) has 21,800 ha and is contiguous to the Sooretama Biological Reserve (SBR), which has an area of 24,150 ha and is administrated by the Brazilian Environmental Agency (IBAMA). Both conservation units constitute the largest remaining forest patch in the state of Espírito Santo and are considered here as a single study area.

Climate is tropical hot and humid, with an average annual precipitation of 1051 mm and an average annual temperature of 23ºC. The predominant vegetation is tropical rain forest of the Tertiary tablelands ("Mata de Tabuleiros"), which is a semi-deciduous, mesophytic forest formation of the Atlantic forest domain. The original vegetation of the VRDNR is typically forest (JESUS 1987). The vegetation at SBR also consists primarily of forest, though swampy vegetation is found at the edges of rivers and streams. The other felids of the VRDNR/SBR include the jaguar, Panthera onca (Linnaeus, 1758); the puma, Puma concolor (Linnaeus, 1771); the ocelot, L. pardalis; and the oncilla, L. tigrinus.

We determined the diet of the margay and the jaguarundi through the collection and analysis of scats. Field collection occurred monthly from April 1995 to September 2000. We collected all fecal samples on the roads which were later identified as either margay or jaguarundi based on the presence of hairs that are ingested during self-grooming. We distinguished between margays and jaguarundis feces through the cuticle pattern of the guard-hair (QUADROS & MONTEIRO-FILHO 2006a). We prepared slides for the analysis of the guard-hair micro-structure (QUADROS & MONTEIRO-FILHO 2006b). Three independent analyses of the sample under an optical microscope (Model U-MDOB3, Olympus) were done.

The distinction between the scats of small cats relied solely in the identification of guard-hair. This was done because it was not always possible to record footprints next to the samples. When footprints occurred, there was a high chance to make an identification error. To avoid this problem, discrimination between Leopardus spp. and P. yagouaroundi was made by differentiating the pattern of cuticular morphology. This pattern in the jaguarundi is unique among small cats due to the guard-hair cuticle having a broad diamond format. The cuticular pattern of the margay guard-hair is unique among species of Leopardus Gray, 1842 by having the standard elongate petal. The cuticular pattern of the oncilla resembles a broad petal and the one from the ocelot resembles a medium petal.

Scats were oven-dried and washed on a sieve. The screened material, such as hair, teeth, and scales were identified using a reference collection as well as through comparison with the material deposited at the Zoological Collection of Museu de Biologia Professor Mello Leitão (Santa Teresa, Espírito Santo, Brazil). Of the 59 fecal samples examined, 30 contained margay hair and nine contained jaguarundi hair. Twenty samples could not be assigned by our analysis and have not been included in the research. We analyzed the importance of each kind of prey based on the percentage of scats that contained a particular prey type (frequency of occurrence) and on the percentage of items (percentage of occurrence).

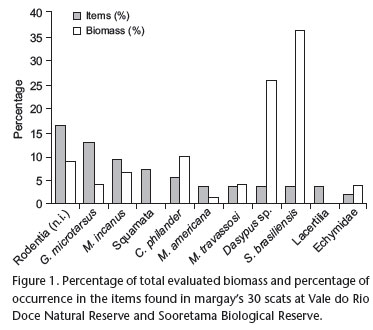

We estimated the mean biomass of each taxon consumed by margay. The average weight of each mammal prey consumed was multiplied by the number of individuals found (evaluated biomass = prey's average weight x number of individuals in the scats). We considered the presence of an item as a single individual except in the case of teeth, where the minimum number of individuals was estimated from the number of teeth found in the sample. The relative importance of each mammal prey was expressed as a percentage in relation to the weight of all the items. We obtained the estimated weight of prey taxa from the literature (EMMONS & FEER 1997, FONSECA et al. 1996) or from data on species deposited in the collection of Museu de Biologia Professor Mello Leitão.

We found 12 items in margay fecal samples. Mammals were the most consumed item occurring in 77% of the fecal samples and accounting for 60% of the total items. Birds and reptiles occurred in 29% and accounted for 10% of the total items consumed, respectively (Tab. I). Among mammals, Didelphimorphia was the most consumed order, with 34% of the frequency of occurrence and the Brazilian gracile mouse opossum, Gracilinanus microtarsus (Wagner, 1842) was found in 13% of the samples analyzed. In relation to the consumed biomass, we observed that the most important item preyed by the margay were the tapeti, Sylvilagus brasiliensis (Linnaeus, 1758); the armadillo, Dasypus sp.; and the bare-tailed woolly opossum, Caluromys philander (Linnaeus, 1758), although the frequency of occurrence of these items in the fecal samples was of only 7% for the first two species and 10% for the last one (Fig. 1).

We identified eight prey types in the fecal samples of the jaguarundi. Birds were the most consumed items and occurred in 55% of the fecal samples and in 41% of the total items. Reptiles occurred in 41% and in 17% of the total items, respectively (Tab. I). Among the mammals, Didelphimorphia was the most consumed order (33% of the total items) followed by Rodentia (8%). In relation to the mammalian biomass consumed, C. philander was the most important item (Tab. I).

In Belize and in Kartabo, Guiana, the margay also consumed arboreal mammals and birds (BEEBE 1925, KONECNY 1989) but in state of São Paulo, Brazil, the terrestrial mammals were the most important items (WANG 2002). In this study, the terrestrial mammals were consumed in lower proportions than in other places (Tab. II). All localities are found within the tropical forest. This may indicate an opportunistic behavior by margays in which the more vulnerable and abundant prey are targeted in each place.

KONECNY (1989) observed a margay feeding upon a rodent five meters above the ground. XIMENEZ (1982) also observed one individual catching a guan, Penelope obscura (Hellmay, 1914), sitting two meters up in a tree and quickly disappearing into the canopy. AZEVEDO (1996) observed a margay climbing a bamboo tree and remained there for approximately 20 minutes trying to capture a bird that was about six meters above the ground.

Although other felids can prey on arboreal mammals, like the ocelot, L. pardalis (EMMONS 1987, MIRANDA et al. 2005, MORENO et al. 2006, BIANCHI & MENDES 2007, ABREU et al. 2008) or big cats (PEETZ et al. 1992, LUDWIG et al. 2007), only the margay has anatomical adaptations that allow it to move about in trees, descending a tree head down - e.g. large claws, proportionally longer tail and the ability of the hind feet to rotate 180 degrees (OLIVEIRA 1994). This species has been observed to exhibit high ability for movements on trees (XIMENEZ 1982, KONECNY 1989, PASSAMANI 1995, AZEVEDO 1996, SOLÓRZANO-FILHO 2006). The ability to forage in different strata (e.g. ground level and above-ground level) may give the margay an advantage over other small cats.

In Belize, small mammals were the most frequently consumed prey by jaguarundi. In Venezuela, reptiles and birds were also important items (BISBAL 1986, MONDOLFI 1986). Birds have been mentioned as the most common food item (CABRERA & YEPPES 1960, KONECNY 1989) and jaguarundi is known to prey on poultry throughout most of their range (OLIVEIRA 1994). MCCARTHY (1992) reported attempted prey on an iguana, Iguana iguana (Linnaeus, 1758), by jaguarundi and reptiles were also important items in Northeastern (Piauí) (OLMOS 1993) and Southeastern (Linhares) (FACURE & GIARETTA 1996), Brazil (Tab. II).

Although there are few studies investigating the diet of jaguarundis and margays and sample sizes are therefore insufficient for quantitative comparisons, there is indication suggesting major prey type segregation between these two felids. That seems to be related to the stratum where each species forages and the pattern of activity (Tab. II). Margays prey more frequently upon arboreous mammals than jaguarundis, which in turn prey more frequently upon birds and reptiles than margays. KILTIE (1984) found no significant differences on craniometric and body size measurements between margays and jaguarundis and suggested that these two species may coexist as a result of differences in habitat use and/or daily activity pattern. This seems to be confirmed in the study of DI BITETTI et al. (2010) in Argentina, where there was a negative association between margays and jaguarundis on camera-traps records; in addition, there was no overlap in activity pattern between these species, with activity peaks differing by 11-12 hours intervals. In Belize, jaguarundis occurred significantly more in old field patches, whereas margays preferred late second growth forests; additionally, while jaguarundis were active during the day, margays were predominantly nocturnal (KONECNY 1989). Therefore, spatial and temporal segregations can be important factors allowing the co-existence of these sympatric species with similar sizes and habits.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Museu de Biologia Professor Mello Leitão for the technical support and O Boticário Foundation of Nature Protection for financial support. We are grateful Abi T. Vanack and Natalie Olifiers for their valuable comments and for help in English version.

LITERATURE CITED

Submitted: 14.XII.2009; Accepted: 02.I.2011.

- ABREU, K.C.; R.F. MORO-RIOS; J.E. SILVA-PEREIRA; J.M.D. MIRANDA; E.F. JABLONSKI & F.C. PASSOS. 2008. Feeding habits of ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) in Southern Brazil. Mammalian Biology 73: 407-411.

- AZEVEDO, F.C.C. 1996. Notes on the behavior of the margay Felis wiedii (Schinz, 1821), (Carnivora, Felidae), in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Mammalia 60: 325-328.

- BEEBE, W. 1925. Studies of a tropical jungle; one quarter of a square mile of jungle at Kartabo, British Guiana. Zoologica 6: 1-193.

- BIANCHI, R.C. & S.L. MENDES. 2007. Feeding habits of ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) in Southern Brazil. American Journal of Primatology 69: 1173-1178.

- BISBAL, F.J. 1986. Food Habitat of Some Neotropical Carnivores in Venezuela (Mammalia, Carnivora). Mammalia 50: 329-339.

- CABRERA, A. & J. YEPPES. 1960. Mamíferos Sud Americanos: vida, costumbres y descripcion. Historia Natural Ediar. Buenos Aires: Companhia Argentina de Editores.370 p.

- CROOKS, K.R. & M.E. SOULÉ. 1999. Mesopredator release and avifaunal extinctions in a fragmented system. Nature 400: 563-566.

- DIBITETTI, M.S.; C.D. DEANGELO; Y.E. DIBLANCO & A. PAVIOLO. 2010. Niche partitioning and species coexistence in a Neotropical felid assemblage. Acta Oecologica 36: 403-412.

- EMMONS, L.H. 1987. Comparative feeding ecology of felids in a Neotropical rainforest. Behavioral Ecology Sociobiology 20: 271-283.

- EMMONS, L.H. & F. FEER. 1997. Neotropical Rainforest Mammals: A Field Guide. Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2nd ed., 307p.

- FACURE, K.G. & A.A. GIARETTA. 1996. Food Habits of Carnivores in a Coastal Atlantic Forest of Southeastern Brazil. Mammalia 60 (3): 499-502.

- FONSECA, G.A.B.; G. HERMANN; Y.L.R. LEITE; R.A. MITTERMEIER; A.B. RYLANDS & J.L. PATTON. 1996. Lista Anotada dos Mamíferos do Brasil. Washington, D.C., Conservation Internacional, Fundação Biodiversitas, Occasional Papers 4, 38p.

- GITTLEMAN, J.L. & M.E. GOMPPER. 2005. The importance of carnivores for understanding patterns of biodiversity and extinction risk, p. 370-388. In: P. BARBOSA & I. CASTELLANOS (Eds). Ecology of Predator-Prey Interactions. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- JESUS, R.M. 1987. Mata Atlântica de Linhares: Aspectos Florestais, p. 35-53. In: SEMA/IWRB/CVRD (Ed.). Desenvolvimento Econômico e Impacto Ambiental em Áreas de Trópico Úmido Brasileiro - A Experiência da CVRD. Rio de Janeiro, CVRD.

- KILTIE, R.A. 1984. Size ratios among sympatric neotropical cats. Oecologia 61: 411-416.

- KONECNY, M.J. 1989. Movement Patterns and Food Habitats of Four Sympatric Carnivore Species in Belize, Central America, p. 243-264. In: K.H. REDFORD & J.F. EISENBERG (Eds). Advances in Neotropical Mammalogy. Gainesville, Sadhill Crane Press.

- LUDWIG, G.; L.M. AGUIAR; J.M.D. MIRANDA; G.M. TEIXEIRA; W.K. SVOBODA; L.S. MALANSKI; M.N. SHIOZAWA; C.L.S. HILST; I.T. NAVARRO & F. PASSOS. 2007. Cougar Predation on Black-and-Gold Howlers on Mutum Island, Southern Brazil. International Journal of Primatology 28 (1): 39-46.

- MANZANI, P.R.& E.L.A. MONTEIRO-FILHO. 1989. Notes on the Food Habitats of the Jaguarundi, Felis yagouaroundi (Mammalia: Carnivora). Mammalia 53 (4): 659-660.

- MCCARTHY, T.J. 1992. Notes Concerning the Jaguarundi Cat (Herpailurus yagouaroundi) in the Caribbean Lowlands of Belize and Guatemala. Mammalia 56 (2): 302-306.

- MIRANDA, J.M.D.; I.P. VERNARDI; K.C. ABREU & F.C. PASSOS. 2005. Predation on Alouatta guariba clamitans Cabrera (Primates, Atelidae) by Leopardus pardalis (Linnaeus) (Carnivora, Felidae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 22:793-795.

- MONDOLFI, E. 1986. Notes on the Biology and Status of the Small Wild Cats in Venezuela, p. 125-146. In: S.D. MILLER & D.D. EVERET (Eds). Cat of the World: Biology, Conservation, and Management. Washington D.C., Natural Wildlife Federation.

- MORENO, R.S.; R.W. KAYS & R. SAMUDIO. 2006. Competitive release in diets of ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) and puma (Puma concolor) after jaguar (Panthera onca) decline. Journal of Mammalogy 87: 808-816.

- OLIVEIRA, T.G. DE 1994. Neotropical cats: ecology and conservation. São Luís, EDUFMA. 220p.

- OLIVEIRA, T.G. DE 1998a. Hepailurus yagouaroundi Mammalian Species 578: 1-6.

- OLIVEIRA, TG. DE 1998b. Leopardus wiedii Mammalian Species 579: 1-6.

- OLMOS, F. 1993. Notes on the Food Habitats of the Brazilian "Caatinga" Carnivores. Mammalia 57 (1): 126-130.

- PASSAMANI, M. 1995. Field Observation of a Group of Geoffroy's Marmosets Mobbing a Margay Cat. Folia Primatologica 64: 163-166.

- PEETZ, A.; M.A. NORCONK & W.G. KINZEY. 1992. Predation by jaguar on howler monkey (Alouatta seniculus) in Venezuela. American Journal of Primatology 28: 223-228.

- QUADROS, J. & E.L.A. MONTEIRO-FILHO. 2006a. Revisão conceitual, padrões microestruturais e proposta nomenclatória para os pêlos-guarda de mamíferos brasileiros. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 23 (1): 279-292.

- QUADROS, J. & E.L.A. MONTEIRO-FILHO. 2006b. Coleta e preparação de pêlos de mamíferos para identificação em microscopia óptica. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 23 (1): 274-278.

- SOLÓRZANO-FILHO, J.A. 2006. Mobbing of Leopardus wiedii while hunting by a group of Sciurus ingrami in an Araucaria forest of Southeast Brazil. Mammalia 70 (1-2): 156-157.

- SUNQUIST, M.& F. SUNQUIST. 2002. Wild Cats of the World. Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 452p.

- TERBORGH, J. 1992. Maintenance of diversity in tropical forests. Biotropica 24: 283-292.

- TERBORGH, J.; J.A. ESTES; P. PAQUET; K. RALLS; D. BOYD-HEGER; B.J. MILLER & R.F. NOSS. 1999. The role of top carnivores in regulating terrestrial ecosystems, p. 39-65. In: SOULÉ, M. E. & J. TERBORGH (Eds). Continental Conservation: Scientific Foundations of Regional Reserve Networks. Washington, D.C., Island Press.

- TERBORGH. J.; L. LOPEZ; P.V. NUÑEZ; M. RAO; G. SHAHABUDDIN; G. ORIHUELA; M. RIVEROS; R. ASCANIO; G.H. ADLER; T.D. LAMBERT & L. BALBAS. 2001. Ecological meltdown in predator-free forest fragments. Science 294: 1923-1926.

- WANG, E. 2002. Diets of ocelots (Leopardus pardalis), margays (Leopardus wiedii), and oncillas (Leopardus tigrinus) in the Atlantic rainforest in southeast Brazil. Studies Neotropical Fauna and Environmental 37: 207-212.

- XIMENEZ, A. 1982. Nota sobre felidos neotropicales VIII Observaciones sobre el Contenido Estomacal y el Comportamiento Alimentar de Diversas Espécies de Felinos. Revista Nordestina de Biologia 5 (1): 89-91.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

21 Mar 2011 -

Date of issue

Feb 2011

History

-

Received

14 Dec 2009 -

Accepted

02 Jan 2011