ABSTRACT

The purpose of this article is to analyze China’s trade and investment relations with Latin America, especially with Brazil and MERCOSUR in the context of the international economic crisis. In a scenario in which commodity prices appear to remain low, the region increases its dependence on China. Thus, the Chinese take advantage to advance on the economies of the region, increasing reprimarization of the economies of these countries.

KEYWORDS:

Chinese investments; Latin America; reprimarization; commodities; Mercosur

RESUMO

O objetivo deste artigo é analisar as relações de comércio e investimento da China com a América Latina, especialmente com o Brasil e o MERCOSUL, no contexto da crise econômica internacional. Em um cenário em que os preços das commodities parecem permanecer baixos, a região aumenta sua dependência da China. Assim, os chineses aproveitam para avançar nas economias da região, aumentando a reprimarização das economias desses países.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE:

Investimentos chineses; América Latina; reprimarização; commodities; Mercosul

INTRODUCTION

When the current United States’ president took office, Geopolitics would not wait to get back at him, The Economist magazine pointed out. After all, “little more than a week after Donald Trump’s victory, Xi Jinping, president of the world’s second-largest economy, set off for Latin America - his third trip there since 2013 - clutching a sheaf of trade deals” (Economist, 2016ECONOMIST, The (2016). “Latin America and China: A Golden opportunity”. 17/11/2016. Available online: Available online: https://www.economist.com/news/americas/21710307-chinas-president-ventures-donald-trumps-backyard-golden-opportunity

access 07/31/2016.

https://www.economist.com/news/americas/...

). Chinese initiatives, investments and inroads were being made long before the change of government in Washington, but at a time “when the image of the big, bad yanqui seems to be making a comeback, Mr Xi may find himself with an opportunity to boost Chinese influence in the American backyard” (Economist, 2016ECONOMIST, The (2016). “Latin America and China: A Golden opportunity”. 17/11/2016. Available online: Available online: https://www.economist.com/news/americas/21710307-chinas-president-ventures-donald-trumps-backyard-golden-opportunity

access 07/31/2016.

https://www.economist.com/news/americas/...

). Just days after Trump’s election and his penchant for threats, vitriol and ripping up trade deals, Beijing released a white paper calling Latin America and the Caribbean a “land of vitality and hope” (Foreign Policy, 2017FOREIGN POLICY (2017). “China steps into the Latin American void that Trump has left behind

”. By: Kevin Gallagher. Available online: Available online: http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/06/china-steps-into-the-latin-american-void-trump-has-left-behind

/ Access 07/31/2017.

http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/06/chin...

).

South America experienced a period of relative bonanza in the first decade of the 21st century, due to the appreciation of commodities in the global market. The economies of the region had had China as the main buyer of its exports of agroindustrial products, metals and hydrocarbons. This demand for natural and energetic resources by the Chinese colossus strengthened the countries’ cash position in that period and contributed to the expansion of the “autonomy margin of the economies of South America” (ECLAC, 2016aECLAC (2016a). Horizontes 203. A Igualdade no centro do desenvolvimento sustentável. Santiago: CEPAL, 2016a., p. 42).

This favorable economic scenario in the region began to revert around 2012, on account of the effects of the global financial crisis that erupted from 2008 onwards and pushed down commodity prices. Since then, the world economy, with rare exceptions, endures low economic growth. In this period, China recorded 10% annual growth until 2012 and about 7% in the following years. The economic slowdown of the United States, Europe and Japan contrasts with the Chinese dynamism and reinforces its position of economic and geopolitical power in the international order.

On average, in 2016 Latin American economies contracted for the second consecutive year and growth rose around 1% percent in 2017. In addition, the international private sector withdraws from the region at an alarming rate, causing negative net capital flows to Latin America for the first time since 1998. Trade policies, but also institutions such as the World Bank to which Latin America could appeal to boost their economies, move at an uncertain pace with the election of Donald Trump (FOREIGN POLICY, 2017FOREIGN POLICY (2017). “China steps into the Latin American void that Trump has left behind

”. By: Kevin Gallagher. Available online: Available online: http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/06/china-steps-into-the-latin-american-void-trump-has-left-behind

/ Access 07/31/2017.

http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/06/chin...

). In this context, China is attempting to increase trade with the region by US$ 500 billion and foreign investment to US$ 250 billion by 2025. Proof of this is the fact that the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China allocate more funding to Latin America than the total sum offered by the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the Andean Development Corporation (CAF) each year.

As Abdenur (2017)ABDENUR, Adriana Erthal (2017). “Skirting or Courting Controversy? Chinese FDI in Latin American Extractive Industries”. In: CARBONNIER, G. et al. (Org.). Alternative Pathways to Sustainable Development: Lessons from Latin America, International Development Policy No.9 (Geneva, Boston: Graduate Institute Publications, Brill-Nijhoff), pp. 174-198. points out, “sweeping statements about China’s role in Latin American Countries tend to overlook the highly variable forms and effects of China’s investments in the region - not to mention the fact that many, if not most, major projects announced never see the light of day” (p. 175). The author stresses that Chinese investments have been concentrated heavily in the region’s major commodities exporters, especially Venezuela and Brazil, and extractive nodes like Chile and Peru (Abdenur, 2017ABDENUR, Adriana Erthal (2017). “Skirting or Courting Controversy? Chinese FDI in Latin American Extractive Industries”. In: CARBONNIER, G. et al. (Org.). Alternative Pathways to Sustainable Development: Lessons from Latin America, International Development Policy No.9 (Geneva, Boston: Graduate Institute Publications, Brill-Nijhoff), pp. 174-198.).

In a report on Chinese investments in Latin America, the British magazine The Economist described the economic partnership between the Asian country and our region “a golden opportunity” (Economist, 2016ECONOMIST, The (2016). “Latin America and China: A Golden opportunity”. 17/11/2016. Available online: Available online: https://www.economist.com/news/americas/21710307-chinas-president-ventures-donald-trumps-backyard-golden-opportunity

access 07/31/2016.

https://www.economist.com/news/americas/...

). Imports of raw materials, copper, iron, oil and soybeans account for three quarters of the region’s exports to China, in addition to a variety of products. But the impact on employment in the region is questionable. The Economist magazine notes that a Boston University study shows that exports to China generated 17% fewer jobs per dollar than exports to other countries. The magazine also cites that a study published by the Atlantic Council, a Washington think tank, concludes that Chinese exports “affected the deindustrialization of the region”. Alerting to the geopolitical intentions of the Asian giant, the magazine makes it clear that the United States loses most, not only in economic but political terms, with the election of Donald Trump at a time when China further boosts its relations with Latin America.

In Brazil, the first four months of 2017 alone, China’s capital amounted to about US$ 6 billion in mergers and acquisitions, leading the investments in the country, even with economic and political uncertainties. China takes advantage of president Michel Temer’s government liberalization wave to expand asset acquisitions in the Brazilian market, with emphasis on the energy and mining sectors in line with its ‘going global’ strategy (Acyoli and Leão, 2011).

Brazilian foreign policy, which had already lost momentum at the end of Rousseff’s first term (2011-2014), was adrift. The Brazilian agenda for South America lost ground and the MERCOSUR crisis worsened. This retreat of Brazilian diplomacy inside and outside the region restores the Country on the route of a regressive international insertion and, at a moment when Donald Trump’s United States disengages from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), withdraws from the Agreement of Paris (2015) and seizes the banner of economic and commercial protectionism, Brazil loses opportunities for its absence of a policy for its strategic environment.

The purpose of this article is to analyze China’s trade and investment relations with South America, especially with Brazil and MERCOSUR in the context of the international economic crisis.

BRAZIL, CHINA AND THE LATIN AMERICAN SPACE

Despite the economic crisis and political uncertainty in Brazil, in 2016 Brazil received US$ 59 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI) from the total of US$ 145 billion invested in Latin America (Valor, 2017aVALOR ECONÔMICO. “País é 6º destino preferido do investidor externo, diz Unctad”. 08/06/2017 a.). A significant portion of this amount comes from China, which ranks as the second largest investor in the world, behind only the United States. However, as the region’s main economy, Brazil finds difficult to diversify its trade relations with the Asian power.

The intensification of the presence of Chinese businesses in Latin America, and especially in South America, has received different reactions from analysts and scholars. There are those who regard economic and trade relations between China and Latin America as complementary and therefore mutually beneficial. In its pages a few months ago, the US magazine Foreign Policy also points out that “with economic ties with the United States more uncertain than ever, Latin America would do well to solidify those ties with China, but with caution” (Foreign Policy, 2017FOREIGN POLICY (2017). “China steps into the Latin American void that Trump has left behind

”. By: Kevin Gallagher. Available online: Available online: http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/06/china-steps-into-the-latin-american-void-trump-has-left-behind

/ Access 07/31/2017.

http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/06/chin...

). However, other analysts emphasize the economic asymmetries and the reprimarization of the export agenda, forming a new dependency (Ferchen, 2011FERCHEN, M. (2011) “As relações entre China e América Latina: impactos de curta ou longa duração?”. Revista Sociologia e Política, vol.19, supl.1, p. 105-130.; Jenkins, 2015JENKIS, R. (2015). “La expansión global de China y su impacto en América Latina”. In: BACA, S. (org.). La expansión de China en América Latina. Ecuador: CELAEP, p. 13-53.).

The optimistic trend tends to value the complementarity relation, since the increase of the Chinese demand for raw materials would contribute to the development of the countries of the region. The pessimistic trend, however, points out that China poses a threat to exports of manufactured goods from the South (JENKINS, 2015JENKIS, R. (2015). “La expansión global de China y su impacto en América Latina”. In: BACA, S. (org.). La expansión de China en América Latina. Ecuador: CELAEP, p. 13-53.). There would be a rerun of the well-known center-periphery relationship, this time in relation to China. This asymmetric relationship is characterized by ECLAC as being of the North-South type (ECLAC, 2016aECLAC (2016a). Horizontes 203. A Igualdade no centro do desenvolvimento sustentável. Santiago: CEPAL, 2016a.).

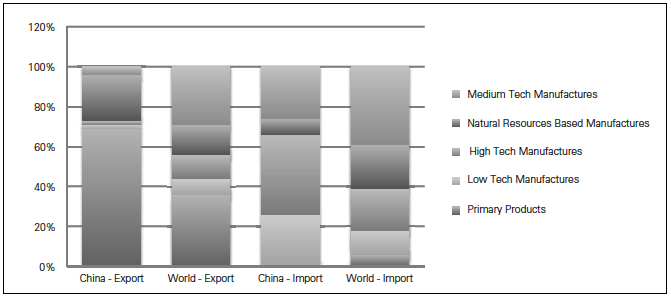

An ECLAC study (2015)ECLAC (2015). América Latina y el Caribe y China Hacia una nueva era de cooperación económica. Santiago, 2015. on economic cooperation between Latin America and China shows the dependence of the region on the Chinese market for the export of primary products clearly. Meanwhile, China sells high, medium and low technology manufactures to Latin American countries. The trend, according to ECLAC, indicates that China will increase its trade and economic presence in Latin America and the Caribbean. The data shows how China’s recent and intense trade relations with the region have grown over the past decade and a half. In 2000 China bought about 1% out of the region and exported almost nothing to it. A decade later it was close to 10% and it is projected that by 2020 it will surpass a traditional partner, that is, the European Union. Despite China’s growing importance in trade with Latin America, the United States continues to be a key partner for the region as a whole, even with the downsizing of its economy’s dynamism after the 2008 crisis (Klemi and Menezes, 2016KLEMI, A. M.; MENEZES, R. G. (2016) “Brasil e Mercosul: rumos da integração na lógica do neo-desenvolvimentismo (2003-2014)”. Caderno CRH (UFBA. Impresso), p. 135-150.).

For China the main markets are Asia, the European Union and the United States. The share of Latin America is small compared to these other three regions and countries. For the countries of the region, especially those in South America, trade with China is fundamental: of the total goods exported to China in 2014 by the region, Brazil sent 42.6% (US$ 40.6 billion), followed by Chile with 19.4% (US$ 18.4 billion), Venezuela 10.8% (US$ 10.3 billion), Peru 7.3% (US$ 6.9 billion), Mexico 6.3% (US$ 5.9 billion), Colombia 5.9% (US$ 5.6 billion) and Argentina 4.9% (US$ 4.6 billion). Of the total exports of goods by Latin America and the Caribbean to the Chinese market, these seven countries exported 97.2%, that is, trade relations with China do not cover the region as a whole. Leaving Mexico’s participation, South America accounts for 91% of the total (Eclac, 2015ECLAC (2015). América Latina y el Caribe y China Hacia una nueva era de cooperación económica. Santiago, 2015.).

According to Acioly and Leão (2011)ACIOLY, Luciana; LEÃO, Rodrigo P. (2011). “A China na nova configuração global”. In: ACIOLY, L. et all (Org.). Internacionalização de Empresas: experiências internacionais selecionadas. Brasília: IPEA, p. 54-77.), Chinese direct foreign investment has two essential characteristics: (i) the concentration of investments in the primary and services sectors, as well as (ii) the concentration of investments in regions with abundance in natural resources and important financial centers. This characteristic of Chinese economic policy mirrors recent trade trends, that is, the increasing integration of world production through global value chains in a process that connects developed and developing countries, revealing the importance of exponential price increases of agricultural products and natural resources since the 2000s. In addition, the main vectors of foreign investment are state-owned enterprises in sectors such as petrochemical, energy and mining, revealing the preference of the Chinese government for the type of investment seeking.

To this end, in 2002 the Chinese State began a new phase of internationalization of the country’s enterprises known as “going global”, approved at the 16th Communist Party Congress. The main focus of this strategy is to ensure access to natural resources through the acquisition of energy and food industries driven by resource diplomacy. According to Acioly and Leão (2011)ACIOLY, Luciana; LEÃO, Rodrigo P. (2011). “A China na nova configuração global”. In: ACIOLY, L. et all (Org.). Internacionalização de Empresas: experiências internacionais selecionadas. Brasília: IPEA, p. 54-77., there are five goals pursued by the Going Global program:

The first was to change the Chinese state’s intervention pattern in order to assume a position of greater regulation of the system rather than directly controlling the sectoral / spatial distribution of the direct investments made by the country. The second was intended to decentralize and relax the licensing concessions for Chinese enterprises. The third objective was to broaden the incentives for the internationalization of enterprises and eliminate exit barriers to investment. The fourth was related to the reduction of capital control and the creation of new financing channels for investments abroad. The latter aimed at integrating the policy of internationalization of Chinese enterprises into other existing policies for the external sector as a way of accelerating the process of integration with countries where China had already established trade or foreign policy relations (Acioly and Leão, 2011ACIOLY, Luciana; LEÃO, Rodrigo P. (2011). “A China na nova configuração global”. In: ACIOLY, L. et all (Org.). Internacionalização de Empresas: experiências internacionais selecionadas. Brasília: IPEA, p. 54-77., p. 70 - our translation).

Essentially, the Chinese State seeks to secure sources of energy and food supplies through the internationalization of its enterprises via acquisitions in these two sectors and thus ensure both the process of growth and expansion of its economy and meet the food needs of its population. On one hand, the increase in the volume of foreign direct investment - in 2016 it was US$ 183 billion - deepening its insertion in global value chains, and on the other, the process of internationalization of companies, fostering the opening of the economy, strengthening of industrial policy and economic development. This process is marked by the decisive presence of the Chinese State. In this context, we must understand the growing commercial involvement between China and South America in recent years, revealing the country’s presence in the region as a way to strengthen its expansion project (Veiga and Rios, 2015VEIGA, Pedro M.; RIOS, Sandra (2015). “Investimentos diretos da China na América do Sul: evolução, controvérsias e perspectivas”. Revista Brasileira de Comercio Exterior. n° 123 abr.-jun., p. 26-37.).

As Graph 1 demonstrates, the energy sector was the leading area of attraction of Chinese investments in 2018 in Brazil, for example:

Chinese Investments in Brazil divided by Sector (announced vs confirmed) 2018 | Analysis by number of project

The following chart (Graph 2), about China’s types of investments in Brazil, demonstrates that, in just over a decade, the greenfield modality grew almost fivefold and merges & acquisitions jumped from 2 between 2007-2009 to 16 in 2018. The joint ventures maintained around 3 in that same period. In Graph 3, each of these modalities is presented in percentage terms:

Form of Entry of The Chinese Investments in Brazil (announced and confirmed) | 2007 - 2018 | Analysis by number of projects

Form of Entry of Chinese Investments in Brazil (confirmed) | 2018 Analysis by nymber of projects

The preference for the Chinese government’s resource seeking in expand its market relations with South American countries generated positive impacts in relation to the region’s growth with the increase in the prices of primary products, according to ECLAC (2016a)ECLAC (2016a). Horizontes 203. A Igualdade no centro do desenvolvimento sustentável. Santiago: CEPAL, 2016a.. However, the decline in commodity prices from 2012 onwards and the unequal trade between the countries of the region and the Chinese State result in a dependent growth.

As Ilan Bizberg (2018)BIZBERG, Ilan (2018). “Varieties of capitalism, growth and redistribution in Asia and Latin America”. Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, vol. 38, nº 2 (151) , pp. 261-279, April-June/2018. Available at: Available at: http://www.rep.org.br/PDF/151-3.PDF

Access on 06/07/2018.

http://www.rep.org.br/PDF/151-3.PDF...

demonstrates, both Latin America and Asia observed an impressive growth of their economies from the turn of the century until 2013. However, the author points out that the mode of development of Asia, as characterized mainly by China, is more sustainable than the one followed by Latin America, and the stakes are high for the Latin American countries:

[...] from the turn of the century until 2013, in Latin America, growth was, for the first time since ISI (1940s to end of the 1970s), accompanied by a diminution of the great inequality that has characterized this continent due to both a decisive effort of redistribution and the effects of economic growth. In fact, one of the characteristics of the mode of development adopted by many Latin American countries during the commodity super cycle (especially Brazil and Argentina) was to redistribute in order to expand the internal market, allow for the growth of the middle classes and impulse economic growth; a wage led growth (Boyer, 2014). In the midst of the present economic and (notably in Brazil) also political crisis, the question of the sustainability of the growth mode followed by these countries is forcibly posed, and the stability of the gains in terms of reduced inequality and poverty and the growth of the middle classes is also raised (Bizberg, 2018BIZBERG, Ilan (2018). “Varieties of capitalism, growth and redistribution in Asia and Latin America”. Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, vol. 38, nº 2 (151) , pp. 261-279, April-June/2018. Available at: Available at: http://www.rep.org.br/PDF/151-3.PDF Access on 06/07/2018.

http://www.rep.org.br/PDF/151-3.PDF... , p. 262).

CHINESE INVESTMENT IN SOUTH AMERICA: DIVERSIFICATION OF SECTORS?

Since 2002, the profile of Chinese investments and activities in the Latin American market has been guided by the “going global” strategy with external investments of the resource seeking type, led by state-owned companies to acquire the necessary inputs to the chain and control of the sources of fundamental raw materials to the Asian giant’s production process. In general terms, FDI has shown that the relative scarcity of natural resources in the country has resulted in an investment pattern focused on the energy and commodities sector (Veiga and Rios, 2015VEIGA, Pedro M.; RIOS, Sandra (2015). “Investimentos diretos da China na América do Sul: evolução, controvérsias e perspectivas”. Revista Brasileira de Comercio Exterior. n° 123 abr.-jun., p. 26-37.; Zhang, 2011ZHANG, J (2011). “China’s Energy Security: Prospects, Challenges, and Opportunities”. The Brookings Institution Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies. Washington D.C. Available online: Available online: http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2011/7/china%20energy%20zha ng/ 7_china_energy_zhang_paper.pdf

. Access 04/02/2017.

http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/researc...

).

Thus, among the 100 most internationalized companies in the world in 2008 (at the beginning of the international financial crisis), 13 were Chinese. Companies such as CITIC, China State Construction Engineering Corporation and Sinochen have about 20% of their assets abroad, with Cosco being the most internationalized of them with more than 70% (Veiga and Rios, 2015VEIGA, Pedro M.; RIOS, Sandra (2015). “Investimentos diretos da China na América do Sul: evolução, controvérsias e perspectivas”. Revista Brasileira de Comercio Exterior. n° 123 abr.-jun., p. 26-37.; UNCTAD, 2010). In 2010 alone, the top 10 Chinese state-owned purchase projects broke the US$ 1 billion mark, exemplified in the purchase of companies such as Statoil, Galp and Repsol (Acioly and Leão, 2011ACIOLY, Luciana; LEÃO, Rodrigo P. (2011). “A China na nova configuração global”. In: ACIOLY, L. et all (Org.). Internacionalização de Empresas: experiências internacionais selecionadas. Brasília: IPEA, p. 54-77.; Schuffner, 2012SCHÜFFNER, C. (2012). “Repsol e Sinopec têm US$ 1 bi para o pré-sal”. Jornal O Estado de S. Paulo. Available at: Available at: http://www.portosenavios.com.br/site/noticias-do-dia /industria-naval-e-offshore/15665-repsol-e-sinopec-tem-us-1-bi-para-o-pre-sal

. Access: 04/02/2017

http://www.portosenavios.com.br/site/not...

).

However, after the slowdown in the world economy because of the 2008 crisis, is it possible to determine a change in China’s performance towards economic and trade relations with the two main MERCOSUR members - Brazil and Argentina? In the face of ongoing transformations in international financial and monetary systems, is it possible to say that China is implementing a second “going global”, broadening its strategy to other sectors?

From 2007 to 2012, low productivity, falling GDP, declining consumption and rising unemployment ended up affecting the US economy and its domino effect on other world economies. In 2008, the US was the world’s largest importers with a total sum of about US$ 2.2 trillion and third place in the list of major exporters with a volume of US$ 1.8 trillion. With its multinationals in more than 193 countries, when the US economy went into recession, the volume of its imports significantly decreased, affecting countries around the world, mainly China and Brazil.

As Abdenur (2017)ABDENUR, Adriana Erthal (2017). “Skirting or Courting Controversy? Chinese FDI in Latin American Extractive Industries”. In: CARBONNIER, G. et al. (Org.). Alternative Pathways to Sustainable Development: Lessons from Latin America, International Development Policy No.9 (Geneva, Boston: Graduate Institute Publications, Brill-Nijhoff), pp. 174-198. points out “faced with a variety of institutional barriers to entry and new sources of uncertainty, Chinese companies tend to ‘test the water’ through mergers and acquisitions, as well as joint ventures, before delving into direct mining or drilling” (p. 177). The author explains that this cautious approach is “driven not only by profit-seeking but also by a more immediate desire to skirt political controversy, which makes China less salient in Latin American public debates as compared to debates in other regions” (p. 176). And in the instances when Chinese firms do invest in greenfield projects, especially large-scale initiatives with considerable environmental footprints and social impact, Abdenur stresses that “these are subject to broader contestation, especially on the part of local civil society groups, and risk becoming the subject of negative coverage by Latin American as well as external media outlets” (Abdenur, 2017ABDENUR, Adriana Erthal (2017). “Skirting or Courting Controversy? Chinese FDI in Latin American Extractive Industries”. In: CARBONNIER, G. et al. (Org.). Alternative Pathways to Sustainable Development: Lessons from Latin America, International Development Policy No.9 (Geneva, Boston: Graduate Institute Publications, Brill-Nijhoff), pp. 174-198., p. 176).

In Brazil, the sectors that received the most investments from Chinese companies were those of commodities (mainly minerals) and energy. In 2009, China assumed the position of Brazil’s first trading partner. During this period, Brazilian exports to China reached US$ 20 billion. Brazilian imports from China reached a level of US$ 15 billion, resulting in a favorable balance to Brazil of almost US$ 5 billion (Estadão, 2010ESTADAO (2010). “China foi o principal parceiro comercial do País em 2009”. Available online: Available online: https://economia.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,china-foi-o-principal-parceiro-comercial-do-pais-em-2009,495806

Access: 08/30/2019.

https://economia.estadao.com.br/noticias...

).

This relationship is characterized by a realignment of FDI activities in Brazil. This is achieved by granting long-term investments to implement a market-seeking strategy with the potential to establish an export platform oriented to Latin America and Brazil (Veiga and Rios, 2015VEIGA, Pedro M.; RIOS, Sandra (2015). “Investimentos diretos da China na América do Sul: evolução, controvérsias e perspectivas”. Revista Brasileira de Comercio Exterior. n° 123 abr.-jun., p. 26-37.; Pinto, 2011PINTO, E. C. (2011). “O eixo sino-americano e as transformações do sistema mundial: tensões e complementaridades comerciais, produtivas e financeiras”. In: LEÃO, R.; PINTO, ACIOLY, L. (Orgs.). A China na nova configuração global. Brasília: IPEA, p. ). According to a study published by ECLAC in 2016, from the Latin American and Caribbean perspective, export diversification appears as the main pending subject: only five products, all primary, accounted for 69% of the value of regional shipments to China in 2015. The dynamics of Chinese direct foreign investment in the region it reinforces this pattern, since almost 90% of said investment between 2010 and 2015 he went to extractive activities, in particular mining and hydrocarbon production (ECLAC, 2016bECLAC (2016b). Relaciones económicas entre América Latina y\el Caribe y China. Oportunidades y desafios. Santiago, p. 6). Another study, in 2018, demonstrated that, between 2005 and 2017, foreign direct investment from China not only showed strong concentration in terms of sectors (with mining and hydrocarbons accounting for about 80%) but in terms of the destination countries, with Brazil, Peru and Argentina receiving 81% of the total (UN, 2018UN (2018). CEPAL vê alta do investimento chinês na América Latina e no Caribe em 2017. Available online: Available online: https://nacoesunidas.org/cepal-ve-alta-do-investimento-chines-na-america-latina-e-no-caribe-em-2017/

Access on 08/30/2019.

https://nacoesunidas.org/cepal-ve-alta-d...

).

Of the total acquisitions, 30% were in the primary sector (18 projects), 47% in the secondary sector (28 projects) and 23% in the tertiary sector (14 projects). Chinese investments over the course of 2007 to 2012 included a range of sectors that go beyond the search for natural resources. The automotive sector had great relative importance with 13 projects announced, followed by others from the industrial sector such as electronics, machinery and equipment. Regarding the differentiation of sectors, considering the number of projects announced, the automobile sector reached the level of 25% on average, while the energy sector concentrated 12% and that of telecommunications and consumer electronics reached a combined average of 15% over a period of five years (2007-2012) (China-Brazil Business Council, 2013CHINA-BRAZIL BUSINESS COUNCIL. (2013). China Investments in Brazil from 2007-2012: A review of recent trends”. ).

During this period, 60 investment projects were identified, by 44 Chinese companies, totaling US$ 24.4 billion. The trend, less concentrated in commodities, reveals two different realities: in South America the pattern persists in the search for natural resources, while in Brazil one observes the advance for the manufacturing or service sectors (Ferrin, 2016FERRIN, Fernanda (2016). “Investimento chinês no Brasil cresce e começa a se diversificar”. Folha de S. Paulo, 2016. Available online: Available online: http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2016/08/180271 8-investimento-chines-no-brasil-cresce-e-comeca-a-se-diversificar.shtml

. Access 04/02/2017.

http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/201...

). This diversification of investments indicates three phases of the Chinese operation and seems to reveal a substantial transition in the direction of its investments in the region: (i) the first phase was sustained by the demand for natural resources, in order to satisfy the demand for minerals, oil and gas natural, in addition to agricultural products; (ii) the second shows the first sign of transition, targeting sectors such as energy, telecommunications and infrastructure projects; (iii) more recently, Chinese investors have turned their activities to the capital goods, automotive and electronics sectors (Oliveira, 2016OLIVEIRA, Henrique A. (2016). “Brasil-China: uma parceria predatória ou cooperativa?” Tempo no mundo, v.2, n.1, Brasília, 2016, p. 143-161.; China-Brazil Business Council, 2013CHINA-BRAZIL BUSINESS COUNCIL. (2013). China Investments in Brazil from 2007-2012: A review of recent trends”. ).

Latin America and the Caribbean: Structure of the Exports to the World and to China divided by Technological Intensity, 2015 (in Percentages)

This change in the profile of Chinese investments in South America, according to UNCTAD data, indicates that FDIs directed to South America are mostly concentrated in natural resources, but in Brazil’s case, new industrial policy measures have encouraged investments in other activities, especially in the automotive sector (UNCTAD, 2013UNCTAD - CONFERÊNCIA DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS SOBRE COMÉRCIO E DESENVOLVIMENTO. World Investment Report 2013: global value chains: investment and trade for development. Geneva: UNCTAD, 2013.). In addition to resource seeking, China works on two other fronts: diversifying its market (market seeking) and efficiency seeking. As Dunning points out (1997, 1993DUNNING, J. (1993). “Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy”. New York, NY: Addison-Wesley.), “there are four main drivers for FDI, that is, natural resource-seeking, market-seeking, efficiency-seeking, and strategic asset-seeking” (p. 104-5)1 1 For an analysis of each of the types of motivation or determinants that lead firms to produce in the international market see Priscila G. Castro and Antônio C. Campos “Uma discussão sobre o comportamento do investimento estrangeiro direto diante de crises financeiras”, Revista Pesquisa e debate, 2018, p. 23-49. .

The automotive sector is the one that has attracted the most Chinese investments in Brazil, and this can contribute to a technological innovation in the Brazilian industrial park.

Thus, the industrial and financial sectors gained relative importance between 2014 and 2015, valuing segments of the automotive sector, appliances and heavy machinery, as well as the telephony and energy sectors. In general, Chinese investments in Brazil fluctuated between 2010 and 2016. The slowdown in the world economy and the need to boost its productive capacity led China to invest in new segments of the Brazilian domestic market. China, once focused almost exclusively on the acquisition of natural resources and investments in the primary sectors, reveals its new facet as a global player. The diversification of investments translates into the search for assets in the areas of technology, finance and real estate:

Between 2011 and 2013, it is possible to notice a gradual change in the profile of Chinese investments in Brazil. During this period, Chinese companies sought new opportunities in the industrial area, particularly in the machinery and equipment, automotive and electronics sectors, in view of the Brazilian domestic market. [...] The process of diversification of Chinese investments in Brazil continued with a subsequent interest in the service sector, especially in the financial sphere. A third moment of the bilateral relationship begins approximately in 2013, when Chinese banks. In a second moment, Chinese companies sought new opportunities in the industrial area, considering the Brazilian domestic market. These companies were established in Brazil or acquired equity interests in Brazilian or international banks already operating in Brazil. […] (China-Brazil Business Council, 2017CHINA-BRAZIL BUSINESS COUNCIL. (2017). Chinese Investments in Brazil 2016. São Paulo., p. 8).

In Brazil, Chinese investments have grown and gradually begun to diversify. This is a result of Chinese demand for new markets, acquisition of new technologies and expansion of its influence beyond its regional scope. In line with its performance in recent years, through the participation and acquisition of several multinational companies on a global scale of business, China puts Brazil in its new phase of investments, characterizing some kind of “going global number 2”, this time more diversified.

China’s recent investments in South America have branched out, according to The Economist (2016)ECONOMIST, The (2016). “Latin America and China: A Golden opportunity”. 17/11/2016. Available online: Available online: https://www.economist.com/news/americas/21710307-chinas-president-ventures-donald-trumps-backyard-golden-opportunity

access 07/31/2016.

https://www.economist.com/news/americas/...

. In September 2016, China’s State Grid bought a 23% stake in Brazilian energy company CPFL for US$ 1.8 billion. WTorre, a Brazilian construction company, has signed an agreement with China Communications and Construction Company International to build a port in Maranhão. Chinese financial companies are also getting involved. Fosun, an investment company, also bought, in 2016, a controlling stake in Rio Bravo, which manages assets in São Paulo. In the year 2015, Bank of Communications bought 80% of BBM, a Brazilian lender, for 525m reais (US$ 174 million). In neighboring Argentina, also in 2015, the government of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, then president, signed a US$ 1 billion agreement to buy Chinese fighters and ocean patrol vessels. Christina also passed an agreement giving the Chinese the right to build a satellite-tracking station in the province of Neuquén, in Argentine Patagonia. After criticizing the agreement before his election in November 2015, the new president, Mauricio Macri, approved the deal. The Chinese say the site has no military purpose and was designed as part of a lunar mission to be launched in 2017. But satellite experts say some of the equipment may also have military uses. The Economist magazine calls attention to the fact that the facility operator is a unit of the People’s Liberation Army, the name of all Chinese military services (Economist, 2016ECONOMIST, The (2016). “Latin America and China: A Golden opportunity”. 17/11/2016. Available online: Available online: https://www.economist.com/news/americas/21710307-chinas-president-ventures-donald-trumps-backyard-golden-opportunity

access 07/31/2016.

https://www.economist.com/news/americas/...

).

MERCOSUR AND TRADE WITH CHINA IN THE POST-2008 PERIOD

In less than a decade and a half, China has become a crucial destination for Latin America’s primary products and already occupies the position of first or second trading partner in several countries of the region. By 2013, about 80% of the region’s exports to the Chinese market were concentrated on only five primary products (oil, soybean, iron ore, copper and sugar), a significant increase from 47% primary products exported in 2000. According to ECLAC, this shows “the strong reprimarization process that has taken place since then” (2015ECLAC (2015). América Latina y el Caribe y China Hacia una nueva era de cooperación económica. Santiago, 2015., p. 43).

The main explanation for the strong increase in trade relations between China and Latin America is that the Chinese economic growth between 2000 and 2012 was 10% per year. With the unfolding of the 2008 international crisis, China’s growth slowed down and thus so did the demand for raw materials, observed in the first decade of the twenty-first century. Between 2010 and 2016, the MERCOSUR trade balance with China showed a positive balance only in 2011 and 2016, showing a relative competitiveness loss of its exports, as shown in the table below:

The reduction in MERCOSUR’s exports to the Chinese market from 2012 is explained by the reduction in world commodity prices. In addition, the impacts of the slowdown of the Chinese economy bring about major growth problems in Latin America, where are affected by their dependence on volatile primary product prices and the relationship with the Asian giant, which is clearly growing below its potential (ECLAC, 2015ECLAC (2015). América Latina y el Caribe y China Hacia una nueva era de cooperación económica. Santiago, 2015.). However, despite dependence on primary products and the lack of diversification of the export agenda, South American countries could recover in the face of increased flows and new business opportunities. This would be possible with the increase of the Chinese economy in the innovation sector and could contribute to create favorable conditions for the development of the South American region (ECLAC, 2015ECLAC (2015). América Latina y el Caribe y China Hacia una nueva era de cooperación económica. Santiago, 2015.).

However, unlike the investment process, the trade established by Brazil / China - MERCOSUR / China continues to maintain its standards. In recent years, Chinese growth has made it the second-largest economy in the world and has favored increased trade relations with South American countries. It is interesting to note that the growing trade relationship between Brazil and Asia (more specifically China), fed the relative decline in trade relations between Brazil and Latin America. In this way, the integration potential of the region is negatively affected by the insertion of China in the Brazilian market, causing it to lose space in the trade indicators of other countries in the region. MERCOSUR and its integrationist potential lose relative importance in trade flows and in the dynamism of the region, reducing, as an economic block, its importance in global value chains (Oliveira, 2016OLIVEIRA, Henrique A. (2016). “Brasil-China: uma parceria predatória ou cooperativa?” Tempo no mundo, v.2, n.1, Brasília, 2016, p. 143-161.).

Over the last few years, the theme has been the same, with little room for variation in the flow of trade between the two countries and in the block as a whole. Within MERCOSUR, approximately US$ 311 billion were exported over six years. However, history has repeated itself, and products such as soy (US$ 118 billion), iron ore (US$ 82 billion) and oil (US$ 31 billion) still reign as major exponents of the export agenda, reaffirming the assertion of previous years and accounting for more than 70% of the total exported value. In terms of imports, the scenario changes drastically. Manufactured products make up almost the whole range of imported products, demonstrating the dichotomy between what is sold to the foreign market and what is bought with more added value. Technology sector products such as screens for microcomputers, circuits and cell phone terminals integrate the range of the five main imported products. Thus, Brazil continually loses its industrial share in the composition of the export agenda, which is much more a loss of competitiveness than a domestic deindustrialization process. In any case, the loss of competitiveness is mainly due to the inability to maintain attractiveness in the face of Chinese and Asian products. In this way, China’s demand for commodities compensates for lost revenues due to the retraction of imports of manufactured goods (Oliveira, 2016OLIVEIRA, Henrique A. (2016). “Brasil-China: uma parceria predatória ou cooperativa?” Tempo no mundo, v.2, n.1, Brasília, 2016, p. 143-161., p. 158).

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century Brazil and China have gradually increased their trade relations. Then, in 2009, China becomes Brazil’s main trading partner, surpassing the United States, which stood in the position for over eighty years. Nonetheless, the steady increase in trade flows may distort the real impacts on the Brazilian economy and development.

One of the concerns of the Chinese presence in the region is with regard to the possible effects on MERCOSUR. Even when China did not represent a significant percentage of the member countries’ trade, at the XXVI Meeting of the Common Market Council held in July 2004 in Puerto Iguazú, the presidents “reaffirmed their desire to deepen economic and trade relations between the economic block and China Popular Republic. In this regard, they welcomed the holding of the Fifth Dialogue between both parties in Beijing, in which the MERCOSUR-China Enlace Group was formed and decided to initiate a feasibility study on a possible trade agreement “(MRE, 2004MRE - MINISTÉRIO DAS RELAÇÕES EXTERIORES. Resenha de Política Exterior. 2004, vol. 1., p. 307). Since then, MERCOSUR does not seem to have defined a collective strategy for dealing with the Chinese giant. Ferrer (2015)FERRER, Aldo (2015). “La construcción...”, Página 12, 22.mar, 5p. Available online: Available online: https://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/suplementos/cash/17-8364-2015-03-24.html

Access: 06/06/2018.

https://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/suple...

points to this central point: MERCOSUR members need to agree on their policies for China.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

In this paper we analyze the growth of investment and trade between South America and China. The increase in Chinese presence poses challenges for the countries of the region, and especially for MERCOSUR. However, the political and economic crisis in Brazil, the region’s main economy, weakens the country’s position in the regional and international scenarios.

One of the main effects of the Brazilian economic crisis is the increasing loss of competitiveness of its economy and consequently of markets in South America. Add to this a new wave of liberalization carried out by the government of Michel Temer with the deregulation of sectors such as energy and oil (in the case oil and gas reserves in the so-called “pre-salt layer” on the country’s maritime coast) and civil aviation. This has facilitated the acquisition of companies by Chinese capital. While on the one hand the diversification of Chinese investments goes beyond the global going strategy, on the other hand it intensifies the Brazilian dependence on the primary sector.

Although China remains Brazil’s main trading partner, the current government does not hide its preference for closer relations with the United States. Since December 2016 when China has achieved market economy status in the World Trade Organization its presence as world economic and political power has been consolidating.

Without a concerted strategy to deal with the Chinese colossus, the MERCOSUR countries clash and negotiate improperly with Beijing. In a scenario in which commodity prices appear to remain low and under the effects of the 2008 international crisis, South America increases its dependence on China. Thus, the Chinese take advantage to advance on the economies of the region.

REFERENCES

- ABDENUR, Adriana Erthal (2017). “Skirting or Courting Controversy? Chinese FDI in Latin American Extractive Industries”. In: CARBONNIER, G. et al. (Org.). Alternative Pathways to Sustainable Development: Lessons from Latin America, International Development Policy No.9 (Geneva, Boston: Graduate Institute Publications, Brill-Nijhoff), pp. 174-198.

- ACIOLY, Luciana; LEÃO, Rodrigo P. (2011). “A China na nova configuração global”. In: ACIOLY, L. et all (Org.). Internacionalização de Empresas: experiências internacionais selecionadas Brasília: IPEA, p. 54-77.

- BIZBERG, Ilan (2018). “Varieties of capitalism, growth and redistribution in Asia and Latin America”. Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, vol. 38, nº 2 (151) , pp. 261-279, April-June/2018. Available at: Available at: http://www.rep.org.br/PDF/151-3.PDF Access on 06/07/2018.

» http://www.rep.org.br/PDF/151-3.PDF - CASTRO, Priscila G.; CAMPOS, Antônio C. (2018). “Uma discussão sobre o comportamento do investimento estrangeiro direto diante de crises financeiras”. Revista Pesquisa e Debate V. 29, n. 1 (53) , p. 23-49.

- CHINA-BRAZIL BUSINESS COUNCIL. (2017). Chinese Investments in Brazil 2016 São Paulo.

- CHINA-BRAZIL BUSINESS COUNCIL. (2013). China Investments in Brazil from 2007-2012: A review of recent trends”.

- DUNNING, J. (1993). “Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy”. New York, NY: Addison-Wesley.

- DUNNING, J. (1977). “Trade, Location of Economic Activity and the MNE: A Search for an Eclectic Approach.” The International - Allocation of Economic Activity, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- DUSSEL PETERS, Enrique (coord.) (2017). “América Latina y China - Economía, comercio e inversión ”. Unión de Universidades de América Latina, UNAM, RED ALC-China, Ciudad de México, México, pp. 279-298. ISBN: 978-607-8066-28-5.

- ECLAC (2015). América Latina y el Caribe y China Hacia una nueva era de cooperación económica Santiago, 2015.

- ECLAC (2016a). Horizontes 203. A Igualdade no centro do desenvolvimento sustentável Santiago: CEPAL, 2016a.

- ECLAC (2016b). Relaciones económicas entre América Latina y\el Caribe y China. Oportunidades y desafios Santiago

- ECONOMIST, The (2016). “Latin America and China: A Golden opportunity”. 17/11/2016. Available online: Available online: https://www.economist.com/news/americas/21710307-chinas-president-ventures-donald-trumps-backyard-golden-opportunity access 07/31/2016.

» https://www.economist.com/news/americas/21710307-chinas-president-ventures-donald-trumps-backyard-golden-opportunity - ESTADAO (2010). “China foi o principal parceiro comercial do País em 2009”. Available online: Available online: https://economia.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,china-foi-o-principal-parceiro-comercial-do-pais-em-2009,495806 Access: 08/30/2019.

» https://economia.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,china-foi-o-principal-parceiro-comercial-do-pais-em-2009,495806 - FERCHEN, M. (2011) “As relações entre China e América Latina: impactos de curta ou longa duração?”. Revista Sociologia e Política, vol.19, supl.1, p. 105-130.

- FERRER, Aldo (2015). “La construcción...”, Página 12, 22.mar, 5p. Available online: Available online: https://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/suplementos/cash/17-8364-2015-03-24.html Access: 06/06/2018.

» https://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/suplementos/cash/17-8364-2015-03-24.html - FERRIN, Fernanda (2016). “Investimento chinês no Brasil cresce e começa a se diversificar”. Folha de S. Paulo, 2016. Available online: Available online: http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2016/08/180271 8-investimento-chines-no-brasil-cresce-e-comeca-a-se-diversificar.shtml . Access 04/02/2017.

» http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2016/08/180271 8-investimento-chines-no-brasil-cresce-e-comeca-a-se-diversificar.shtml - FOREIGN POLICY (2017). “China steps into the Latin American void that Trump has left behind ”. By: Kevin Gallagher. Available online: Available online: http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/06/china-steps-into-the-latin-american-void-trump-has-left-behind / Access 07/31/2017.

» http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/06/china-steps-into-the-latin-american-void-trump-has-left-behind - JENKIS, R. (2015). “La expansión global de China y su impacto en América Latina”. In: BACA, S. (org.). La expansión de China en América Latina Ecuador: CELAEP, p. 13-53.

- KLEMI, A. M.; MENEZES, R. G. (2016) “Brasil e Mercosul: rumos da integração na lógica do neo-desenvolvimentismo (2003-2014)”. Caderno CRH (UFBA. Impresso), p. 135-150.

- MRE - MINISTÉRIO DAS RELAÇÕES EXTERIORES. Resenha de Política Exterior. 2004, vol. 1.

- OLIVEIRA, Henrique A. (2016). “Brasil-China: uma parceria predatória ou cooperativa?” Tempo no mundo, v.2, n.1, Brasília, 2016, p. 143-161.

- PINTO, E. C. (2011). “O eixo sino-americano e as transformações do sistema mundial: tensões e complementaridades comerciais, produtivas e financeiras”. In: LEÃO, R.; PINTO, ACIOLY, L. (Orgs.). A China na nova configuração global Brasília: IPEA, p.

- SCHÜFFNER, C. (2012). “Repsol e Sinopec têm US$ 1 bi para o pré-sal”. Jornal O Estado de S. Paulo Available at: Available at: http://www.portosenavios.com.br/site/noticias-do-dia /industria-naval-e-offshore/15665-repsol-e-sinopec-tem-us-1-bi-para-o-pre-sal . Access: 04/02/2017

» http://www.portosenavios.com.br/site/noticias-do-dia /industria-naval-e-offshore/15665-repsol-e-sinopec-tem-us-1-bi-para-o-pre-sal - UNCTAD - CONFERÊNCIA DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS SOBRE COMÉRCIO E DESENVOLVIMENTO. World Investment Report 2013: global value chains: investment and trade for development. Geneva: UNCTAD, 2013.

- UN (2018). CEPAL vê alta do investimento chinês na América Latina e no Caribe em 2017. Available online: Available online: https://nacoesunidas.org/cepal-ve-alta-do-investimento-chines-na-america-latina-e-no-caribe-em-2017/ Access on 08/30/2019.

» https://nacoesunidas.org/cepal-ve-alta-do-investimento-chines-na-america-latina-e-no-caribe-em-2017/ - VALOR ECONÔMICO. “País é 6º destino preferido do investidor externo, diz Unctad”. 08/06/2017 a.

- VALOR ECONÔMICO. “China lidera ranking de aquisições no Brasil”. 24/04/2017b.

- VEIGA, Pedro M.; RIOS, Sandra (2015). “Investimentos diretos da China na América do Sul: evolução, controvérsias e perspectivas”. Revista Brasileira de Comercio Exterior n° 123 abr.-jun., p. 26-37.

- ZHANG, J (2011). “China’s Energy Security: Prospects, Challenges, and Opportunities”. The Brookings Institution Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies Washington D.C. Available online: Available online: http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2011/7/china%20energy%20zha ng/ 7_china_energy_zhang_paper.pdf . Access 04/02/2017.

» http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2011/7/china%20energy%20zha ng/ 7_china_energy_zhang_paper.pdf

-

1

For an analysis of each of the types of motivation or determinants that lead firms to produce in the international market see Priscila G. Castro and Antônio C. Campos “Uma discussão sobre o comportamento do investimento estrangeiro direto diante de crises financeiras”, Revista Pesquisa e debate, 2018CASTRO, Priscila G.; CAMPOS, Antônio C. (2018). “Uma discussão sobre o comportamento do investimento estrangeiro direto diante de crises financeiras”. Revista Pesquisa e Debate. V. 29, n. 1 (53) , p. 23-49., p. 23-49.

-

4

JEL Classification: F02.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

10 June 2020 -

Date of issue

Jul-Sep 2020

History

-

Received

26 June 2018 -

Accepted

11 Sept 2019

Sorce: CEBC.

Sorce: CEBC.

Source: CEBC.

Source: CEBC.

Source: CEBC.

Source: CEBC.

Source:

Source:  Source: China-Brazil Business Co.

Source: China-Brazil Business Co.

Source: CEPAL, CONTRADE.

Source: CEPAL, CONTRADE.