ABSTRACT

Lichens play a key role in natural ecosystems, as they can function as primary producers, recycle minerals and fix nitrogen. Despite their environmental importance, little is known about lichen ecology in Brazil, and especially about how abiotic factors may influence their spatial distribution. In this study, we aimed to verify how the cover and richness of corticolous lichens on Araucaria angustifolia trunks vary between two different habitats (Forest and Grassland). The photoquadrat sampling method was applied to A. angustifolia trunks. The Coral Point Count software with Excel extensions (CPCe) was used to analyze photographs for lichen cover and richness. Additionally, a redundancy analysis was conducted to estimate how five abiotic and two biotic variables affected the spatial distribution of lichens. Twenty-five morphospecies were identified, none of them occurring exclusively in the Grassland habitat. Canopy openness, air humidity and tree trunk rugosity were important parameters influencing lichen distribution; therefore, spatial segregation of growth forms can be explained by environmental selectivity. Foliose lichens require more air humidity, which explains their predominance in the Forest habitat. Canopy openness in Grassland habitat favors fruticose lichens, which depend on factors such as wind for reproduction.

Keywords:

Ascomycota; corticolous lichens; environmental selectivity; fungi; lichen ecology; niche overlap

Introduction

Lichens are symbiotic organisms formed by the association of one or more fungi (Ascomycota and/or Basidiomycota) and microalgae (Cianophyceae or Chlorophyta groups; Beck et al. 1998Beck A, Friedl T, Rambold G. 1998. Selectivity of photobiont choice in a defined lichen community: inferences from cultural and molecular studies. New Phytologist 139: 709-720. ; Marcelli 2006Marcelli MP. 2006. Fungos liquenizados. In: Xavier Filho L, Legaz ME, Cordoba CV, Pereira EC. (eds.) Biologia de líquens. Rio de Janeiro, Âmbito Cultural Edições, Ltda. p. 25-74.; Spribille et al. 2016Spribille T, Tuovinen V, Resl P, et al. 2016. Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens. Science 353: 488-492. ). Lichens exist in a great diversity of shapes and sizes, and are considered a key group in ecosystem functioning for their role as primary producers (Büdel et al. 2014Büdel B, Colesie C, Green TGA, et al. 2014. Improved appreciation of the functioning and importance of biological soil crusts in Europe: The Soil Crust International Project (SCIN). Biodiversity and Conservation 23: 1639-1658.; Munir et al. 2015Munir TM, Perkins M, Kaing E, Strack M. 2015. Carbon dioxide flux and net primary production of a boreal treed bog: Responses to warming and water-table-lowering simulations of climate change. Biogeosciences 12: 1091-1111.), atmospheric nitrogen fixers (Nash 2008Nash TH. 2008. Lichen biology. 2nd. edn. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press .) and for contributing to the cycling and incorporation of soil minerals (Cornelissen et al. 2007Cornelissen JHC, Lang SI, Soudzilovskaia NA, During HJ. 2007. Comparative cryptogam ecology: A review of bryophyte and lichen traits that drive biogeochemistry. Annals of Botany 99: 987-1001. ; Nash 2008Nash TH. 2008. Lichen biology. 2nd. edn. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press .; Concostrina-Zubiri et al. 2013Concostrina-Zubiri L, Huber-Sannwald E, Martínez I, Flores JL, Escudero A. 2013. Biological soil crusts greatly contribute to small-scale soil heterogeneity along a grazing gradient. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 64: 28-36.). Furthermore, lichens are important bioindicators of environmental quality (Lemos et al. 2007Lemos A, Kaffer MI, Martins SA. 2007. Composição e diversidade de líquens corticícolas em três diferentes ambientes: Florestal, Urbano e Industrial. Revista Brasileira de Biociências 5: 228-230.; Gauslaa 2014Gauslaa Y. 2014. Rain, dew, and humid air as drivers of morphology, function and spatial distribution in epiphytic lichens. The Lichenologist 46: 1-16.; Perlmutter et al. 2017Perlmutter GB, Blank GB, Wentworth TR, Lowman MD, Neufeld HS, Rivas Plata E. 2017. Effects of highway pollution on forest lichen community structure in western Wake County, North Carolina, U.S.A. The Bryologist 120: 1-10.).

Lichens develop close interactions with living surfaces, such as tree trunks (Brodo 1973Brodo IM. 1973. Substrate ecology. In: Ahmadjian V, Hale ME. (eds.). The lichens. New York, Academic Press. p. 401-441.). These biological substrates provide favorable environmental conditions for lichen growth, such as substrate complexity and light conditions that are generally adequate for physiological responses by lichens (Brodo 1973Brodo IM. 1973. Substrate ecology. In: Ahmadjian V, Hale ME. (eds.). The lichens. New York, Academic Press. p. 401-441.; Nascimbene et al. 2009Nascimbene J, Marini L, Motta R, Nimis PL. 2009. Influence of tree age, tree size and crown structure on lichen communities in mature Alpine spruce forests. Biodiversity and Conservation 18: 1509-1522. ). In addition, the structural complexity of tree trunks, considering tree age and size, influence lichen richness, as older tree trunks tend to be rougher and favor establishment (Nascimbene et al. 2009Nascimbene J, Marini L, Motta R, Nimis PL. 2009. Influence of tree age, tree size and crown structure on lichen communities in mature Alpine spruce forests. Biodiversity and Conservation 18: 1509-1522. ).

Although lichens are present in different environments, their abundance and distribution are influenced by abiotic factors that facilitate their development (Honda & Vilegas 1998Honda NK, Vilegas W. 1998. The chemistry of lichens. Química Nova 21: 110-125. ; Gauslaa 2014Gauslaa Y. 2014. Rain, dew, and humid air as drivers of morphology, function and spatial distribution in epiphytic lichens. The Lichenologist 46: 1-16.). Light availability and wind speed are among the most important factors, as they influence photosynthetic processes and spore/propagule dispersal, respectively (Heinken 1999Heinken T. 1999. Dispersal patterns of terricolous lichens by thallus fragments. The Lichenologist 31: 603-612.; Palmqvist 2000Palmqvist K. 2000. Carbon economy in lichens. New Phytologist 148: 11-36.; Nash 2008Nash TH. 2008. Lichen biology. 2nd. edn. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press .; Gauslaa 2014Gauslaa Y. 2014. Rain, dew, and humid air as drivers of morphology, function and spatial distribution in epiphytic lichens. The Lichenologist 46: 1-16.). Secondarily, air humidity and temperature determine colonization success, since they enable the photobiont to develop symbiotic interactions (Brodo 1973Brodo IM. 1973. Substrate ecology. In: Ahmadjian V, Hale ME. (eds.). The lichens. New York, Academic Press. p. 401-441.; Benítez et al. 2012Benítez Á, Prieto M, González Y, Aragón G. 2012. Effects of tropical montane forest disturbance on epiphytic macrolichens. Science of the Total Environment 441: 169-175.; Gauslaa 2014Gauslaa Y. 2014. Rain, dew, and humid air as drivers of morphology, function and spatial distribution in epiphytic lichens. The Lichenologist 46: 1-16.). To determine how abiotic conditions influence the success of biological interactions is a key factor in understanding lichen distribution and abundance (Fedrowitz et al. 2012Fedrowitz K, Kaasalainen U, Rikkinen J. 2012. Geographic mosaic of symbiont selectivity in a genus of epiphytic cyanolichens. Ecology and Evolution 2: 2291-2303.; Gauslaa 2014Gauslaa Y. 2014. Rain, dew, and humid air as drivers of morphology, function and spatial distribution in epiphytic lichens. The Lichenologist 46: 1-16.). The effects of abiotic factors on lichen distribution and richness are well known globally, as well as the importance of forest ecosystems as a matrix for lichen colonization and dispersal (Moning et al. 2009Moning C, Werth S, Dziock F, et al. 2009. Lichen diversity in temperate montane forests is influenced by forest structure more than climate. Forest Ecology and Management 258: 745-751.; McMullin et al. 2010McMullin RT, Duinker PN, Richardson DHS, Cameron RP, Hamilton DC, Newmaster SG. 2010. Relationships between the structural complexity and lichen community in coniferous forests of southwestern Nova Scotia. Forest Ecology and Management 260: 744-749.; Gauslaa 2014Gauslaa Y. 2014. Rain, dew, and humid air as drivers of morphology, function and spatial distribution in epiphytic lichens. The Lichenologist 46: 1-16.). However, there are few studies on these factors in Brazilian ecosystems (Martins et al. 2011Martins SMA, Käffer MI, Alves CR, Pereira VC. 2011. Fungos liquenizados da Mata Atlântica, no sul do Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica 25: 286-292.; Käffer & Martins 2014Käffer MI, Martins SMA. 2014. Evaluation of the environmental quality of a protected riparian forest in Southern Brazil. Bosque 35: 325-336. ), especially considering different habitats in Mixed Ombrophilous Forest (araucaria forest), for which there is scarce knowledge on lichen ecology (e.g. Fleig & Grüninger 2008Fleig M, Grüninger W. 2008. Lichens of the Araucaria Forest of Rio Grande do Sul. Pro-Mata: field guide No. 3. Tübingen, University of Tübingen. ; Käffer et al. 2009Käffer MI, Ganade G, Marcelli MP. 2009. Lichen diversity and composition in Araucaria forests and tree monocultures in southern Brazil. Biodiversity and Conservation 18: 3543-3561.; 2010Käffer MI, Marcelli MP, Ganade G. 2010. Distribution and composition of the lichenized mycota in a landscape mosaic of southern Brazil. Acta Botanica Brasilica 24: 790-802.; 2015Käffer MI, Koch NM, Aptroot A, Martins SMA. 2015. New records of corticolous lichens for South America and Brazil. Plant Ecology and Evolution 148: 111-118.; Koch et al. 2012Koch NM, Maluf RW, Martins SMA. 2012. Foliose lichen community on Piptocarpha angustifolia Dusén ex Malme (Asteraceae) in an area of native Araucaria forest in Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil. Iheringia 67: 47-57.; Hampp et al. 2018Hampp R, Cardoso N, Fleig M, Grüninger W. 2018. Vitality of lichens under different light climates in an Araucaria forest (Pró-mata RS, south Brazil) as determined by chlorophyll fluorescence. Acta Botanica Brasilica 32: 188-197.).

Araucaria angustifolia (Araucariaceae) is described as a predominant phytoecological unit in Mixed Ombrophilous Forest (Rondon Neto et al. 2002Rondon Neto RM, Watzlawick LF, Caldeira MVW, Schoeninger ER. 2002. Análise florística e estrutural de um fragmento de floresta ombrófila mista montana, situado em Criúva, RS Brasil. Ciência Florestal 12: 29-37. ). Its distribution covers higher altitude areas between Rio Grande do Sul and Paraná states in southern Brazil, as well as small disconnected areas in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais (Hueck 1953Hueck K. 1953. Distribuição e habitat natural do Pinheiro do Paraná (Araucaria angustifolia) Boletim da Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras, Universidade de São Paulo, Botânica 10: 5-24.). The species has high ecological relevance, although the total cover of Mixed Ombrophilous Forest has been significantly reduced due to logging and conversion to agriculture (Borgo & Silva 2003Borgo M, Silva SM. 2003. Epífitos vasculares em fragmentos de Floresta Ombrófila Mista, Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Botânica 26: 391-401.; Medeiros et al. 2005Medeiros JD, Savi M, Brito BFA. 2005. Seleção de áreas para criação de Unidades de Conservação na Floresta Ombrófila Mista. Biotemas 18: 33-50. ). Araucaria angustifolia is important for the recruitment of different epiphytic and arboreal species, increasing local diversity (Borgo & Silva 2003Borgo M, Silva SM. 2003. Epífitos vasculares em fragmentos de Floresta Ombrófila Mista, Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Botânica 26: 391-401.; Fogaça et al. 2016Fogaça IB, Cerveira A, Scheer GG, Maia H, Gomes TC, Dechoum MS. 2016. Pode Araucaria angustifolia ser considerada uma espécie facilitadora no processo de conversão de campos em florestas? In: Teixeira TR, Agrelo M, Segal B, Hanazaki N, Giehl ELH. (eds.). Ecologia de campo - do mar às montanhas. Florianópolis, PPGECO/UFSC. p. 151-163.). Ecological studies with corticolous lichens associated with A. angustifolia are still incipient (see Käffer et al. 2010Käffer MI, Marcelli MP, Ganade G. 2010. Distribution and composition of the lichenized mycota in a landscape mosaic of southern Brazil. Acta Botanica Brasilica 24: 790-802.), although it is acknowledged that the dominance of a particular lichen morphospecies may be indicative of certain environmental conditions (Nimis et al. 2002Nimis PL, Scheidegger C, Wolseley PA. 2002. Monitoring with lichens - monitoring lichens. NATO Science Series. IV. Earth and Environmental Sciences, 7. Dordrecht, Kluwer Academic Publishers.; Will-Wolf et al. 2006Will-Wolf S, Geiser LH, Neitlich P, Reis AH. 2006. Forest lichen communities and environment - How consistent are relationships across scales? Journal of Vegetation Science 17: 171-184.; Giordani et al. 2009Giordani P, Brunialti G, Benesperi R, Rizzi G, Frati F, Modenesi P. 2009. Rapid biodiversity assessment in lichen diversity surveys: implications for quality assurance. Journal of Environmental Monitoring 11: 730-735.) and anthropogenic effects on natural areas (Dettki & Esseen 1998Dettki H, Esseen PA. 1998. Epiphytic macrolichens in managed and natural forest landscapes: a comparison at two spatial scales. Ecography 21: 613-624.; Das et al. 2012Das P, Joshi S, Rout J, Upreti DK. 2012. Impact of anthropogenic factors on abundance variability among lichen species in southern Assam, north east India. Tropical Ecology 54: 67-72.; Li et al. 2013Li S, Liu WY, Li DW. 2013. Epiphytic lichens in subtropical forest ecosystems in southwest China: Species diversity and implications for conservation. Biological Conservation 159: 88-95.; Bähring et al. 2016Bähring A, Fichtner A, Ibe K, et al. 2016. Ecosystem functions as indicators for heathland responses to nitrogen fertilisation. Ecological Indicators 72: 185-193. ).

Lichens exist in different growth forms as a result of the symbiotic interaction. These are defined as morphotypes. Crustose lichens are sessile and adhered to the substrate; foliose lichens grow leafy, lobular structures anchored in the substrate by a thallus or rhizine; and fruticose lichens have little contact with the substrate and grow as pendent, sub-pendent or shrub-like thallus (Hinds & Hinds 2007Hinds JW, Hinds PL. 2007. The macrolichens of New England. New York, The New York Botanical Garden Press.; Nash 2008Nash TH. 2008. Lichen biology. 2nd. edn. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press .). The symbiont species in the interaction determines the lichen morphospecies, while the spatial distribution of each growth form may be correlated with the habitat where the symbiosis was established. This is justified by the influence of abiotic factors on the development, maintenance or replication of the symbiosis (Fedrowitz et al. 2012Fedrowitz K, Kaasalainen U, Rikkinen J. 2012. Geographic mosaic of symbiont selectivity in a genus of epiphytic cyanolichens. Ecology and Evolution 2: 2291-2303.).

This study aimed to evaluate the influence of abiotic factors (i.e. canopy openness, air humidity, distance to a river, air temperature and wind speed) on the cover and richness of lichen morphospecies and growth forms associated with A. angustifolia (araucaria hereafter) in two different habitats in Mixed Ombrophilous Forest (Forest and Grassland). We hypothesized that differences in abiotic factors and vegetation structure between these habitats result in differences in lichen cover and richness.

Materials and methods

Study area

Field work was conducted in November 2017, in the daytime (9am - 5pm), on the Reunidas Campo Novo farm, located in the municipality of Bom Retiro (27°53'58.28"S 49°26'11.06"W), state of Santa Catarina, in southern Brazil (Fig. 1A). The climate is temperate oceanic, Cfb in the Köppen-Geiger classification system (see Pandolfo et al. 2002Pandolfo C, Braga HJ, Silva Júnior VP, et al. 2002. Atlas climatológico do Estado de Santa Catarina. Florianópolis, Epagri. ). Annual mean rainfall varies between 1500-1700 mm, mean temperature between 17-18 °C, and mean air humidity between 82-84 % in the summer (Pandolfo et al. 2002Pandolfo C, Braga HJ, Silva Júnior VP, et al. 2002. Atlas climatológico do Estado de Santa Catarina. Florianópolis, Epagri. ). Photoquadrat sampling was applied on araucaria trees in two Mixed Ombrophilous Forest habitats at a minimum distance of 360 meters (“Forest” and “Grassland” hereafter). These areas are located next to the João Paulo river. The Forest habitat is situated upstream and represented by riparian vegetation, characterized by high frequency of Araucaria angustifolia (Bertol.) Kuntze trees. The Grassland habitat is located downstream and characterized by the prevalence of herbaceous vegetation, mostly grasses with shrubs, and sparse A. angustifolia trees (Fig. 1B).

Location map of the study area and sampling method used for estimating lichen cover and richness. A. Map of Santa Catarina State, with the location of Bom Retiro (Black square); B. Study area on the Reunidas Campo Novo farm; blue and purple polygons define Forest and Grassland habitats, respectively; C. The photoquadrat used to obtain images for each araucaria tree sampled.

Data collection

In each habitat, four linear transects placed 30 meters apart were set up with the use of a measuring tape. The transects were 50 m long and 10 m wide (comprising an area of 500 m²). The photoquadrat sampling method (Fig. 1C) was applied to all araucaria trees in the transects at least 3 m distant from other araucaria trees and circumference at breast height (CBH) larger than 50 cm.

Canopy openness (measured with a spherical densitometer; Forest Model-C), air humidity (analogic hygrometer, Incotherm, %), distance from the river (measuring tape, meters), air temperature (thermometer, ºC) and wind speed (anemometer Instrutherm THD-500, meters/second) were measured for each araucaria tree. All abiotic variables were measured within a three-hour interval on the northern side of the trunk, at a height of 1.3 meters from the ground. The biotic variables CBH (cm) and trunk rugosity were measured in the same spot of the photoquadrat. Rugosity was visually estimated and categorized as low, medium or high. “Low” rugosity was characterized by smooth irregularities on the trunk, “medium” for shallow grooves and/or light cortex peeling, and “high” as deep grooves and advanced process of cortex peeling (Fig. 2).

Rugosity categories of Araucaria angustifolia trunks (A. low rugosity, B. medium rugosity, C. high rugosity); and growth forms of lichens sampled in Mixed Ombrophilous Forest (D. crustose, morphospecies Herpothallon cf. rubrocinctum, E. foliose, morphospecies Parmotrema sp., F. fruticose, morphospecies Usnea sp.).

The photoquadrat sampling method was adapted from the method described by Kohler & Gill (2006Kohler KE, Gill SM. 2006. Coral Point Count with Excel extensions (CPCe): A visual basic program for the determination of coral and substrate coverage using random point count methodology. Computers and Geosciences 32: 1259-129. ), previously applied in studies on marine benthic organisms. A polyvinyl chloride (PVC) rectangle was placed on the northern side of the trunk, and one 25 x 10 cm (250 cm²) photograph was taken at a minimum distance of 40 cm between the rectangle and the camera (Canon G15). The photographs were analyzed in the laboratory using Coral Point Count software with Excel extensions (CPCe 4.0 version 2006). Richness of morphospecies and cover of each of the three lichen growth forms were obtained by 30 randomly distributed points on each photo. The lichens at each point were identified and classified in one of the three growth forms: crustose, foliose or fruticose (Fig. 2). When the point fell on the cortex, bryophytes or pteridophytes, the element was termed “other”. Once the lichens at each point were identified, the proportion of cover of each growth form was estimated in each photo by extrapolation using the CPCe software. The total cover of 100 % corresponds to the sum of all organisms identified in every photoquadrat, and the total cover of each growth form corresponds to the average of each growth form for all trees sampled in “Forest” and “Grassland”.

Statistical analyses

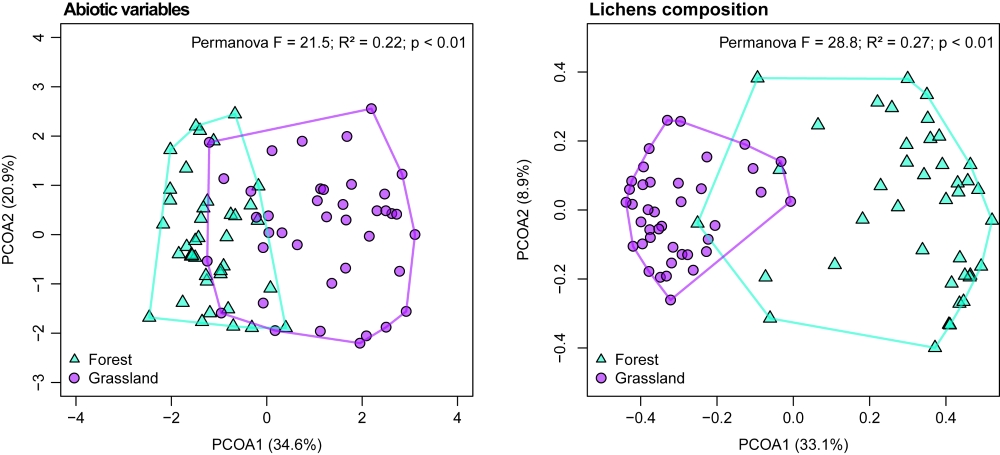

We performed a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) to verify how the samples (tree trunks) were arranged regarding abiotic variables and a permutation analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) to test the null hypothesis that Forest and Grassland do not differ on abiotic terms. Abiotic variables were transformed by standardization to decrease data dispersion. We also performed a PCoA and a PERMANOVA to verify and test how lichen composition (morphospecies) varied between habitats.

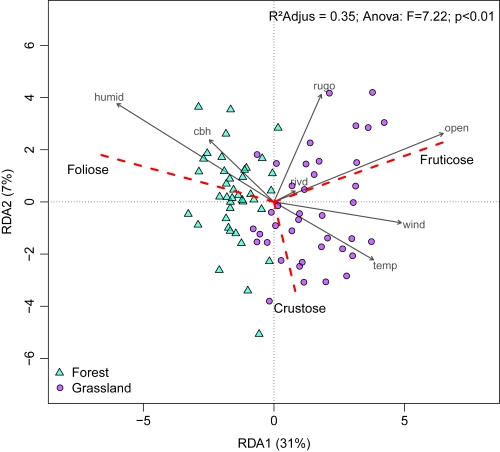

To verify whether total cover and richness; and the cover of growth forms (i.e. crustose, foliose and fruticose) varied between habitats, we performed a Welch’s t-test. To verify the influence of abiotic variables on lichen composition we performed a redundancy analysis (RDA) and a subsequent analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the canonical axes. All analyses were performed using the “vegan” (Oksanen et al. 2013Oksanen JF, Blanchet G, Kindt R, et al. 2013. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.0-10. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan

http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan...

) and “ggplot2” (Wickham 2009Wickham H. 2009. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York, Springer New York.) packages of R software (R Core Team 2017R Core Team. 2017. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing. ).

Results

A total of 80 araucaria trunks were sampled, 40 in each habitat (Forest and Grassland), on which 25 morphospecies of lichens were found. Seven of these were crustose, 11 foliose, and seven fruticose. While no morphospecies were exclusive to Grassland, 13 occurred only in Forest (Tab. 1). Although registered in the photographs, the morphospecies Ramalina cf. usnea and Phyllopsora sp. were not captured in the random point placement method due to restricted cover (Tab. 1).

Morphospecies and growth forms of lichens on Araucaria angustifolia trunks sampled in two habitats (“Forest” and “Grassland”) in Mixed Ombrophilous Forest.

The PCoA and PERMANOVA analyses showed that abiotic factors and lichen composition are different in Forest and Grassland (Fig. 3). Furthermore, in the samples located in Grassland a more diffuse pattern was observed for abiotic factors, with few samples overlapping Forest. On the other hand, samples in Forest presented a more diffuse pattern in lichen composition.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) performed with the abiotic variables and the composition of lichen morphospecies sampled in two habitats: “Forest” (Blue triangles) and “Grassland” (purple circles) in Mixed Ombrophilous Forest.

Lichen total cover differed between habitats (T=21.8; DF=79.1; p<0.01), being higher in Forest (mean=47.9; standard error=±2.5) than in Grassland (46.8 ± 3.4). Total richness also differed (T=14; DF=93.2; p<0.01), being higher in Forest (4.6 ± 0.3) than in Grassland (3.88 ± 0.26). The crustose growth form differed in cover (T=5.6; DF=79.2; p<0.01) and richness (T=-2.5; DF=117.8; p=0.01) between habitats, being higher in Grassland (Fig. 4). The foliose growth form also differed in cover (T=7.1; DF=79.1; p<0.01), but did not differ in richness (T=0.3; DF=93.3; p=0.75); cover was higher in Forest (Fig. 4). Conversely, the fruticose growth form differed in cover (T=7.8; DF=79.1; p<0.01), but did not differ in richness (T=0.1; DF=99.2; p=0.94); cover was higher in Grassland (Fig. 4).

Scatterplot of cover (%) and richness of lichen growth forms (crustose, foliose and fruticose) associated with Araucaria angustifolia tree trunks sampled in two habitats: “Forest” (Blue triangles) and “Grassland” (purple circles) in Mixed Ombrophilous Forest. Black and white diamonds and black bars represent mean and standard errors, respectively.

The RDA analysis showed that canopy openness, air humidity and trunk rugosity were the main abiotic factors influencing cover of the three growth forms (Fig. 5). The foliose growth form was more related to Forest, being positively influenced by humidity and CBH, while the fruticose growth form showed the opposite pattern, being more related to Grassland and positively influenced by canopy openness. The crustose growth form was related to both habitats and inversely related to trunk rugosity (Fig. 5).

Redundancy analysis (RDA) between abiotic variables and lichen growth forms associated with Araucaria angustifolia tree trunks, sampled in two habitats (“Forest” and “Grassland”) in Mixed Ombrophilous Forest. Arrows indicate abiotic variables: “open” - canopy openness; “cbh” - circumference at breast height; “rugo” - trunk rugosity; “temp” - air temperature (°C); humid - air humidity (%); wind - wind speed (m/s). Red dashed lines represent the three growth forms of lichens (crustose, foliose and fruticose).

Discussion

In this study, we verified that the cover and richness of corticolous lichens on A. angustifolia trunks are determined by the environment in which the tree is growing, as a consequence of abiotic variables that can influence the selectivity of lichens for substrate type. The highest total cover and richness of lichens was found in Forest, where samples presented a more scattered pattern, indicating higher variation in species composition compared to Grassland. In terms of growth form, the cover by foliose lichens was higher in Forest, while the cover by fruticose and crustose lichens was higher in Grassland.

The spatial segregation of lichen growth forms between habitats may be indicative of lichen dispersal limitation (Werth et al. 2006Werth S, Wagner HH, Gugerli F, Holderegger R, Csencsics D, Kalwij JM, Scheidegger C. 2006. Quantifying dispersal and establishment limitation in a population of an epiphytic lichen. Ecology 87: 2037-2046.) and/or the effect of abiotic factors on reproductive strategies. Lichens can reproduce asexually (i.e. soredia and isidia) and sexually; and may also produce vegetative propagules (Bowler & Rundel 1975Bowler PA, Rundel PW. 1975. Reproductive strategies in lichens. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 70: 325-340.; Seymour et al. 2005Seymour FA, Crittenden PD, Dyer PS. 2005. Sex in the extremes: lichen-forming fungi. Mycologist 19: 51-58. ). These forms of reproduction result in different dispersal strategies. Sexual spores can be dispersed to long distances by wind and rain (Bowler & Rundel 1975Bowler PA, Rundel PW. 1975. Reproductive strategies in lichens. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 70: 325-340.), whereas asexual reproduction limits dispersal distance but generates new thallus quicker than sexual spores after deposition on a substrate (Seymour et al. 2005Seymour FA, Crittenden PD, Dyer PS. 2005. Sex in the extremes: lichen-forming fungi. Mycologist 19: 51-58. ). For instance, the fruticose growth form was observed in higher proportion in Grassland with a positive influence of canopy openness. Generally, this growth form is known to undergo symbiotic reproduction (i.e. many species of Usnea with fibrils), may have low dispersal capacity, and the growth of new individuals is dependent on the transport of fragments by vectors such as wind (Hinds & Hinds 2007Hinds JW, Hinds PL. 2007. The macrolichens of New England. New York, The New York Botanical Garden Press.). The open canopy in Grassland facilitates dispersal of lichens by wind, which may explain the dominance of the fruticose growth form in this habitat. On the other hand, the foliose anatomy generates high adherence to the substrate, protecting the photobiont between the fungus cortical layers (Büdel & Scheidegger 2008Büdel B, Scheidegger C. 2008. Thallus morphology and anatomy. In: Nash TH. (ed.) Lichen biology. 2nd edn. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. p. 40-68), thus requiring lower wind exposure and higher retention of humidity for the physiological maintenance of the algae (Hinds & Hinds 2007Hinds JW, Hinds PL. 2007. The macrolichens of New England. New York, The New York Botanical Garden Press.; Koch et al. 2013Koch NM, Martins SMDA, Lucheta F, Müller SC. 2013. Functional diversity and traits assembly patterns of lichens as indicators of successional stages in a tropical rainforest. Ecological Indicators 34: 22-30.). Hence, this growth form is favored by lower canopy openness that can act as a physical barrier against desiccation. Thus, we could infer that abiotic parameters influence dispersal ability and limit lichen establishment (Bowler & Rundel 1975Bowler PA, Rundel PW. 1975. Reproductive strategies in lichens. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 70: 325-340.; Scheidegger & Werth 2009Scheidegger C, Werth S. 2009. Conservation strategies for lichens: insights from population biology. Fungal Biology Reviews 23: 55-66.).

Trunks of araucaria trees with high rugosity were less colonized by crustose lichens. The crustose growth form is characterized by high adherence to the substrate (Hinds & Hinds 2007Hinds JW, Hinds PL. 2007. The macrolichens of New England. New York, The New York Botanical Garden Press.), therefore its occurrence is probably limited on trees with a high extent of bark peeling. This was corroborated by the presence of crustose lichens exclusively related to medium and low trunk rugosity in both habitats and less correlated with abiotic parameters. The crustose form is resistant to low light availability and can tolerate water oversaturation due to morphological adaptations (Lakatos et al. 2006Lakatos M, Rascher U, Büdel B. 2006. Functional characteristics of corticolous lichens in the understory of a tropical lowland rain forest. New Phytologist 172: 679-695.). Thus, we may infer that the substrate (characteristics of araucaria trunks) was more relevant in the distribution of crustose lichens than other abiotic conditions.

These observations led to the hypothesis that the distribution of corticolous lichens in Forest and Grassland may be due to the existence of different optimum conditions required for their establishment and growth (Marcelli 1998Marcelli MP. 1998. History and current knowledge of brazilian lichenology. In: Marcelli MP, Seaward MRD. (eds.). Lichenolgy in Latin America: Hystory, current knowledge and applications. São Paulo, CETESB. p. 25-45.; Gauslaa 2014Gauslaa Y. 2014. Rain, dew, and humid air as drivers of morphology, function and spatial distribution in epiphytic lichens. The Lichenologist 46: 1-16.). Especially considering abiotic conditions, water availability or saturation is a key parameter, as it influences CO2 exchange on the surface of the lichen thallus (Harris 1971Harris GP. 1971. The ecology of corticolous lichens II. the relationship between physiology and the environment. Journal of Ecology 59: 441-452.; Lakatos et al. 2006Lakatos M, Rascher U, Büdel B. 2006. Functional characteristics of corticolous lichens in the understory of a tropical lowland rain forest. New Phytologist 172: 679-695.) and acts as a dispersal mechanism for reproductive stages (Scheidegger & Werth 2009Scheidegger C, Werth S. 2009. Conservation strategies for lichens: insights from population biology. Fungal Biology Reviews 23: 55-66.). For instance, in conditions of low humidity, higher canopy openness and higher substrate rugosity (observed in Grassland), there is less substrate available for establishment and less water for the physiological maintenance of the photobiont. These conditions may reduce richness in Grassland when compared to Forest. However, an increase in humidity would create a niche overlap with other species that require increased water availability to survive, such as mosses and ferns (Friedel et al. 2006Friedel A, Oheimb GV, Dengler J, Hardtle W. 2006. Species diversity and species composition of epiphytic bryophytes and lichens - a comparison of managed and unmanaged beech forests in NE Germany. Feddes Repertorium 117: 172-185. ). The niche overlap concept (Pianka 1974Pianka ER. 1974. Niche overlap and diffuse competition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 71: 2141-2145. ) assumes that an environment in which species share their resources may support a more diverse community than those where this partition of resources does not occur. Pianka’s theory reinforces our finding that Forest has the highest species richness considering that the increase in humidity can favor lichen growth, but can also lead to competition for space, affecting their coexistence.

The higher richness of lichen morphospecies observed in Forest was possibly related to the interaction among the abiotic variables in this habitat. These variables were more constant (i.e. lower range of values) than in Grassland, which could favor a diversification of morphospecies. In contrast, the high variability of each abiotic factor in Grassland could act as a “filter effect”. In this case, reduced richness may be related to the ability of species to establish and disperse in this habitat. The filter effect is corroborated by the composition of lichens in each area, with high segregation of the foliose growth form in Forest. Conversely, the interaction of abiotic parameters was more important for determining the composition of crustose and fruticose lichens.

Our study reinforces the importance of abiotic factors in the spatial distribution and species composition of lichen communities on Araucaria angustifolia trunks. As a consequence, we highlight the relevance of conservation of populations of the endangered speciesA. angustifolia(Brasil 2008Brasil. 2008. Instrução normativa n. 6 de 26 de setembro de 2008. Lista oficial das espécies da flora brasileira ameaçadas de extinção. Brasília, MMA.), as well as of the protection of Mixed Ombrophilous Forest remnants in southern Brazil.

Acknowledgements

We thank Eduardo H. Giehl for the assistance with statistical analysis; and Bruna de Ramos for the support with the CPCe software. We also thank to the owners and managers of the Reunidas Campo Novo farm for the structural support.We thank the Programa de Pós-graduação em Ecologia-UFSC for essential financial and field support. LN, GB and MSD are supported by a scholarship from CAPES.

References

- Bähring A, Fichtner A, Ibe K, et al 2016. Ecosystem functions as indicators for heathland responses to nitrogen fertilisation. Ecological Indicators 72: 185-193.

- Beck A, Friedl T, Rambold G. 1998. Selectivity of photobiont choice in a defined lichen community: inferences from cultural and molecular studies. New Phytologist 139: 709-720.

- Benítez Á, Prieto M, González Y, Aragón G. 2012. Effects of tropical montane forest disturbance on epiphytic macrolichens. Science of the Total Environment 441: 169-175.

- Borgo M, Silva SM. 2003. Epífitos vasculares em fragmentos de Floresta Ombrófila Mista, Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Botânica 26: 391-401.

- Bowler PA, Rundel PW. 1975. Reproductive strategies in lichens. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 70: 325-340.

- Brasil. 2008. Instrução normativa n. 6 de 26 de setembro de 2008. Lista oficial das espécies da flora brasileira ameaçadas de extinção. Brasília, MMA.

- Brodo IM. 1973. Substrate ecology. In: Ahmadjian V, Hale ME. (eds.). The lichens. New York, Academic Press. p. 401-441.

- Büdel B, Scheidegger C. 2008. Thallus morphology and anatomy. In: Nash TH. (ed.) Lichen biology. 2nd edn. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. p. 40-68

- Büdel B, Colesie C, Green TGA, et al 2014. Improved appreciation of the functioning and importance of biological soil crusts in Europe: The Soil Crust International Project (SCIN). Biodiversity and Conservation 23: 1639-1658.

- Concostrina-Zubiri L, Huber-Sannwald E, Martínez I, Flores JL, Escudero A. 2013. Biological soil crusts greatly contribute to small-scale soil heterogeneity along a grazing gradient. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 64: 28-36.

- Cornelissen JHC, Lang SI, Soudzilovskaia NA, During HJ. 2007. Comparative cryptogam ecology: A review of bryophyte and lichen traits that drive biogeochemistry. Annals of Botany 99: 987-1001.

- Das P, Joshi S, Rout J, Upreti DK. 2012. Impact of anthropogenic factors on abundance variability among lichen species in southern Assam, north east India. Tropical Ecology 54: 67-72.

- Dettki H, Esseen PA. 1998. Epiphytic macrolichens in managed and natural forest landscapes: a comparison at two spatial scales. Ecography 21: 613-624.

- Fedrowitz K, Kaasalainen U, Rikkinen J. 2012. Geographic mosaic of symbiont selectivity in a genus of epiphytic cyanolichens. Ecology and Evolution 2: 2291-2303.

- Fleig M, Grüninger W. 2008. Lichens of the Araucaria Forest of Rio Grande do Sul. Pro-Mata: field guide No. 3. Tübingen, University of Tübingen.

- Fogaça IB, Cerveira A, Scheer GG, Maia H, Gomes TC, Dechoum MS. 2016. Pode Araucaria angustifolia ser considerada uma espécie facilitadora no processo de conversão de campos em florestas? In: Teixeira TR, Agrelo M, Segal B, Hanazaki N, Giehl ELH. (eds.). Ecologia de campo - do mar às montanhas. Florianópolis, PPGECO/UFSC. p. 151-163.

- Friedel A, Oheimb GV, Dengler J, Hardtle W. 2006. Species diversity and species composition of epiphytic bryophytes and lichens - a comparison of managed and unmanaged beech forests in NE Germany. Feddes Repertorium 117: 172-185.

- Gauslaa Y. 2014. Rain, dew, and humid air as drivers of morphology, function and spatial distribution in epiphytic lichens. The Lichenologist 46: 1-16.

- Giordani P, Brunialti G, Benesperi R, Rizzi G, Frati F, Modenesi P. 2009. Rapid biodiversity assessment in lichen diversity surveys: implications for quality assurance. Journal of Environmental Monitoring 11: 730-735.

- Hampp R, Cardoso N, Fleig M, Grüninger W. 2018. Vitality of lichens under different light climates in an Araucaria forest (Pró-mata RS, south Brazil) as determined by chlorophyll fluorescence. Acta Botanica Brasilica 32: 188-197.

- Harris GP. 1971. The ecology of corticolous lichens II. the relationship between physiology and the environment. Journal of Ecology 59: 441-452.

- Heinken T. 1999. Dispersal patterns of terricolous lichens by thallus fragments. The Lichenologist 31: 603-612.

- Hinds JW, Hinds PL. 2007. The macrolichens of New England. New York, The New York Botanical Garden Press.

- Honda NK, Vilegas W. 1998. The chemistry of lichens. Química Nova 21: 110-125.

- Hueck K. 1953. Distribuição e habitat natural do Pinheiro do Paraná (Araucaria angustifolia) Boletim da Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras, Universidade de São Paulo, Botânica 10: 5-24.

- Käffer MI, Ganade G, Marcelli MP. 2009. Lichen diversity and composition in Araucaria forests and tree monocultures in southern Brazil. Biodiversity and Conservation 18: 3543-3561.

- Käffer MI, Marcelli MP, Ganade G. 2010. Distribution and composition of the lichenized mycota in a landscape mosaic of southern Brazil. Acta Botanica Brasilica 24: 790-802.

- Käffer MI, Martins SMA. 2014. Evaluation of the environmental quality of a protected riparian forest in Southern Brazil. Bosque 35: 325-336.

- Käffer MI, Koch NM, Aptroot A, Martins SMA. 2015. New records of corticolous lichens for South America and Brazil. Plant Ecology and Evolution 148: 111-118.

- Koch NM, Maluf RW, Martins SMA. 2012. Foliose lichen community on Piptocarpha angustifolia Dusén ex Malme (Asteraceae) in an area of native Araucaria forest in Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil. Iheringia 67: 47-57.

- Koch NM, Martins SMDA, Lucheta F, Müller SC. 2013. Functional diversity and traits assembly patterns of lichens as indicators of successional stages in a tropical rainforest. Ecological Indicators 34: 22-30.

- Kohler KE, Gill SM. 2006. Coral Point Count with Excel extensions (CPCe): A visual basic program for the determination of coral and substrate coverage using random point count methodology. Computers and Geosciences 32: 1259-129.

- Lakatos M, Rascher U, Büdel B. 2006. Functional characteristics of corticolous lichens in the understory of a tropical lowland rain forest. New Phytologist 172: 679-695.

- Lemos A, Kaffer MI, Martins SA. 2007. Composição e diversidade de líquens corticícolas em três diferentes ambientes: Florestal, Urbano e Industrial. Revista Brasileira de Biociências 5: 228-230.

- Li S, Liu WY, Li DW. 2013. Epiphytic lichens in subtropical forest ecosystems in southwest China: Species diversity and implications for conservation. Biological Conservation 159: 88-95.

- Marcelli MP. 1998. History and current knowledge of brazilian lichenology. In: Marcelli MP, Seaward MRD. (eds.). Lichenolgy in Latin America: Hystory, current knowledge and applications. São Paulo, CETESB. p. 25-45.

- Marcelli MP. 2006. Fungos liquenizados. In: Xavier Filho L, Legaz ME, Cordoba CV, Pereira EC. (eds.) Biologia de líquens. Rio de Janeiro, Âmbito Cultural Edições, Ltda. p. 25-74.

- Martins SMA, Käffer MI, Alves CR, Pereira VC. 2011. Fungos liquenizados da Mata Atlântica, no sul do Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica 25: 286-292.

- McMullin RT, Duinker PN, Richardson DHS, Cameron RP, Hamilton DC, Newmaster SG. 2010. Relationships between the structural complexity and lichen community in coniferous forests of southwestern Nova Scotia. Forest Ecology and Management 260: 744-749.

- Medeiros JD, Savi M, Brito BFA. 2005. Seleção de áreas para criação de Unidades de Conservação na Floresta Ombrófila Mista. Biotemas 18: 33-50.

- Moning C, Werth S, Dziock F, et al 2009. Lichen diversity in temperate montane forests is influenced by forest structure more than climate. Forest Ecology and Management 258: 745-751.

- Munir TM, Perkins M, Kaing E, Strack M. 2015. Carbon dioxide flux and net primary production of a boreal treed bog: Responses to warming and water-table-lowering simulations of climate change. Biogeosciences 12: 1091-1111.

- Nascimbene J, Marini L, Motta R, Nimis PL. 2009. Influence of tree age, tree size and crown structure on lichen communities in mature Alpine spruce forests. Biodiversity and Conservation 18: 1509-1522.

- Nash TH. 2008. Lichen biology. 2nd. edn. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press .

- Nimis PL, Scheidegger C, Wolseley PA. 2002. Monitoring with lichens - monitoring lichens. NATO Science Series. IV. Earth and Environmental Sciences, 7. Dordrecht, Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Oksanen JF, Blanchet G, Kindt R, et al 2013. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.0-10. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan

» http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan - Palmqvist K. 2000. Carbon economy in lichens. New Phytologist 148: 11-36.

- Pandolfo C, Braga HJ, Silva Júnior VP, et al 2002. Atlas climatológico do Estado de Santa Catarina. Florianópolis, Epagri.

- Perlmutter GB, Blank GB, Wentworth TR, Lowman MD, Neufeld HS, Rivas Plata E. 2017. Effects of highway pollution on forest lichen community structure in western Wake County, North Carolina, U.S.A. The Bryologist 120: 1-10.

- Pianka ER. 1974. Niche overlap and diffuse competition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 71: 2141-2145.

- R Core Team. 2017. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Rondon Neto RM, Watzlawick LF, Caldeira MVW, Schoeninger ER. 2002. Análise florística e estrutural de um fragmento de floresta ombrófila mista montana, situado em Criúva, RS Brasil. Ciência Florestal 12: 29-37.

- Scheidegger C, Werth S. 2009. Conservation strategies for lichens: insights from population biology. Fungal Biology Reviews 23: 55-66.

- Seymour FA, Crittenden PD, Dyer PS. 2005. Sex in the extremes: lichen-forming fungi. Mycologist 19: 51-58.

- Spribille T, Tuovinen V, Resl P, et al 2016. Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens. Science 353: 488-492.

- Werth S, Wagner HH, Gugerli F, Holderegger R, Csencsics D, Kalwij JM, Scheidegger C. 2006. Quantifying dispersal and establishment limitation in a population of an epiphytic lichen. Ecology 87: 2037-2046.

- Wickham H. 2009. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York, Springer New York.

- Will-Wolf S, Geiser LH, Neitlich P, Reis AH. 2006. Forest lichen communities and environment - How consistent are relationships across scales? Journal of Vegetation Science 17: 171-184.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

21 Sept 2018 -

Date of issue

Jan-Mar 2019

History

-

Received

14 Mar 2018 -

Accepted

16 Aug 2018