ABSTRACT

We explored patterns of phenotypic variation in Hemigrammus coeruleus from the Unini River basin, a blackwater river in the Brazilian Amazon. Geometric morphometrics was used to evaluate variation in body shape among populations from four tributaries (UN2-UN5). We found no evidence for sexual dimorphism in body size and shape. However, morphological differences among populations were detected as the analyses recovered significant groups corresponding to each sub-basin, with some overlap among them. The populations from UN2, UN3 and UN5 had more elongate bodies than fish from UN4. The most morphologically divergent population belonged to UN4, the tributary with the most divergent environmental conditions and the only one with seasonally-muddy waters. The morphological variation found among these populations is likely due to phenotypic plasticity or local adaptation, arising as a product of divergent ecological selection pressures among sub-basins. This work constitutes one of the first to employ a population-level geometric morphometric approach to assess phenotypic variation in Amazonian fishes. This method was able to distinguish subtle differences in body morphology, and its use with additional species can bring novel perspectives on the evaluation of general patterns of phenotypic differentiation in the Amazon.

Keywords:

Geometric morphometrics; Morphology; Ornamental fish; Phenotypic plasticity; Populations

RESUMO

Neste estudo foram explorados os padrões de variação fenotípica em Hemigrammus coeruleus da bacia do rio Unini, um rio de água preta na Amazônia brasileira. Métodos de morfometria geométrica foram aplicados para avaliar as variações na forma do corpo entre populações provenientes de quatro tributários (UN2-UN5). Os resultados mostraram ausência de dimorfismo sexual relacionado ao tamanho e formato do corpo. Entretanto, diferenças morfológicas entre populações foram detectadas, uma vez que as análises apontaram agrupamentos correspondendo a cada sub-bacia, com certo grau de sobreposição entre populações. As populações dos rios Preto, Arara e Pauini (UN2, UN3 e UN5) apresentaram formato de corpo mais alongado do que a amostra do igarapé Solimõezinho (UN4). A população mais divergente morfologicamente pertenceu ao igarapé Solimõezinho (UN4), o tributário que apresentou a condição ambiental mais divergente e o único com águas sazonalmente barrentas. A variação morfológica encontrada nessas populações de H. coeruleus é provavelmente devido a plasticidade fenotípica ou adaptação local por seleção induzida por diferentes pressões seletivas entre as sub-bacias. Este estudo constitui a primeira contribuição científica usando métodos de morfometria geométrica para avaliar a variação fenotípica entre populações em peixes amazônicos. Esse método foi capaz de distinguir diferenças sutis na morfologia e sua replicação em outras espécies amazônicas pode trazer novas perspectivas na avaliação de padrões gerais de diferenciação fenotípica na região.

Palavras-chave:

Morfologia; Morfometria geométrica; Peixes ornamentais; Plasticidade fenotípica; Populações

Introduction

Causes and processes driving population divergence have been central aspects of research in evolutionary biology (Bernatchez, 2004Bernatchez L. Ecological theory of adaptive radiation: an empirical assessment from coregonine fishes (Salmoniformes). In Hendry AP, Stearns SC, editors. Evolution illuminated: salmon and their relatives. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. p 175-207.). Intraspecific phenotypic diversification is often produced and maintained by divergent selective regimes (e.g., Langerhans et al., 2003Langerhans RB, Layman CA, Langerhans AK, DeWitt TJ. Habitat-associated morphological divergence in two Neotropical fish species. Biol J Linn Soc . 2003; 80(4):689-698.) arising from either phenotypic plasticity or genetic divergence (Langerhans et al., 2004Langerhans RB, Layman CA, Schrokollahi AM, DeWitt TJ. Predator-driven phenotypic diversification in Gambusia affinis. Evolution. 2004; 58(10):2305-2318.). Although diversification is possible with gene flow (e.g., Gaither et al., 2015Gaither MR, Bernal MA, Coleman RR, Bowen BW, Jones SA, Simison WB, Rocha LA. Genomic signatures of geographic isolation and natural selection in coral reef fishes. Mol Ecol. 2015; 24(7):1543-1557.; Marques et al., 2016Marques DA, Lucek K, Meier JI, Mwaiko S, Wagner CE, Excoffier L, Seehausen O. Genomics of rapid incipient speciation in sympatric threespine stickleback. Plos Genet 2016; 12(2):e1005887.), divergence is more likely to occur among isolated populations (Rundle, Nosil, 2005Rundle HD, Nosil P. Ecological speciation. Ecol Lett. 2005; 8(3):336-352.). Adaptive phenotypic plasticity is predicted to be most advantageous in a heterogeneous environment when future conditions can be reliably predicted (Sultan, Spencer, 2002Sultan SE, Spencer HG. Metapopulation structure favors plasticity over local adaptation. Am Nat . 2002; 160(2):271-283.; Schlichting, Smith, 2002Schlichting CD, Smith H. Phenotypic plasticity: linking molecular mechanisms with evolutionary outcomes. Evol Ecol . 2002; 16(3):189-211.).

Freshwater fishes have often been observed to exhibit adaptation to local environmental conditions and have been widely used to study phenotypic differentiation among populations (Langerhans et al., 2003Langerhans RB, Layman CA, Langerhans AK, DeWitt TJ. Habitat-associated morphological divergence in two Neotropical fish species. Biol J Linn Soc . 2003; 80(4):689-698.; Langerhans et al., 2004Langerhans RB, Layman CA, Schrokollahi AM, DeWitt TJ. Predator-driven phenotypic diversification in Gambusia affinis. Evolution. 2004; 58(10):2305-2318.; Sidlauskas et al., 2006Sidlauskas B, Chernoff B, Machado-Allison A. Geographic and environmental variation in Bryconops sp.cf. melanurus (Ostariophysi: Characidae) from the Brazilian Pantanal. Ichthyol Res . 2006; 53(1):24-33.; Burns et al., 2009Burns JG, Di Nardo P, Rood FH. The role of predation in variation in body shape in guppies Poecilia reticulata: a comparison of field and common garden phenotypes. J Fish Biol. 2009; 75(6):1144-1157.; Wagner et al., 2009Wagner CE, McIntyre PB, Buels KS, Gilbert DM, Michel E. Diet predicts intestine length in Tanganyika’s cichlid fishes. Funct Ecol. 2009; 23(6):1122-1131.; van Rijssel, Witte, 2013van Rijssel JC, Witte F. Adaptive responses in resurgent Lake Victoria cichlids over the past 30 years. Evol Ecol. 2013; 27(2):253-267.). Intraspecific morphological variation has been associated with several ecological variables (Langerhans, DeWitt, 2004Langerhans RB, DeWitt TJ. Shared and unique features of evolutionary diversification. Am Nat. 2004; 164(3): 335-349.; Hendry et al., 2006Hendry AP, Kelly ML, Kinnison MT, Reznick DN. Parallel evolution of the sexes? Effects of predation and habitat features on the size and shape of wild guppies. J Evol Biol. 2006; 19(3):741-754.), environmental factors (Langerhans et al., 2003Langerhans RB, Layman CA, Langerhans AK, DeWitt TJ. Habitat-associated morphological divergence in two Neotropical fish species. Biol J Linn Soc . 2003; 80(4):689-698.; Sidlauskas et al., 2006Sidlauskas B, Chernoff B, Machado-Allison A. Geographic and environmental variation in Bryconops sp.cf. melanurus (Ostariophysi: Characidae) from the Brazilian Pantanal. Ichthyol Res . 2006; 53(1):24-33.; Gomes-Jr., Monteiro, 2008Gomes-Jr JL, Monteiro LR. Morphological divergence patterns among populations of Poecilia vivipara (Teleostei; Poeciliidae): test of an ecomorphological paradigm. Biol J Linn Soc. 2008; 93(4):799-812.; Langerhans, 2008Langerhans RB. 2008. Predictability of phenotypic differentiation across flow regimes in fishes. Integr Comp Biol. 2008; 48: 750-768.; Webster et al., 2011Webster MM, Atton N, Hart PJB, Ward AJW. Habitat-specific morphological variation among threespine sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus) within a drainage basin. PloS ONE . 2011; 6(6):e21060.), and developmental features such as sexual dimorphism (Cox-Fernandes, 1998Cox-Fernandes C. Sex-related morphological variation in two species of apteronotid fishes (Gymnotiformes) from the Amazon River Basin. Copeia. 1998; 1998(3):730-735.; Kitano et al., 2007Kitano J, Mori S, Peichel CL. Sexual dimorphism in the external morphology of the threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus). Copeia . 2007; 2007(2):336-349.) and ontogenetic allometry (Sidlauskas et al., 2006Sidlauskas B, Chernoff B, Machado-Allison A. Geographic and environmental variation in Bryconops sp.cf. melanurus (Ostariophysi: Characidae) from the Brazilian Pantanal. Ichthyol Res . 2006; 53(1):24-33.; García-Alzate et al., 2010García-Alzate CA, Román-Valencia C, González MI. Morfogeometría de los peces del género Hyphessobrycon (Characiformes: Characidae), grupo heterorhabdus, en Venezuela. Rev Biol Trop. 2010; 58(3):801-811.).

Although a large number of fish studies have documented morphological variation due to ecological causes, only a few studies have done so using neotropical species, e.g., Cichlasoma minckleyi (Kornfield, Taylor 1983) (Trapani, 2003Trapani J. Geometric morphometric analysis of body-form variability in Cichlasoma minckleyi, the Cuatro Cienegas cichlid. Environ Biol Fishes . 2003; 68(4):357-369.), Bryconops caudomaculatus (Günther 1864) and Biotodoma wawrini (Gosse 1963) (Langerhans et al., 2003Langerhans RB, Layman CA, Langerhans AK, DeWitt TJ. Habitat-associated morphological divergence in two Neotropical fish species. Biol J Linn Soc . 2003; 80(4):689-698.), Poecilia vivipara Bloch, Schneider 1801 (Neves, Monteiro, 2003Neves FM, Monteiro LR. Body shape and size divergence among populations of Poecilia vivipara in coastal lagoons of south-eastern Brazil. J Fish Biol . 2003; 63(4):928-941.; Monteiro, Gomes-Jr., 2005Monteiro LM, Gomes-Jr. JL. Morphological divergence rates test for natural selection: uncertainty of parameter estimation and robustness of results. Genet Mol Biol. 2005; 28(2):345-355.; Gomes-Jr., Monteiro, 2008Gomes-Jr JL, Monteiro LR. Morphological divergence patterns among populations of Poecilia vivipara (Teleostei; Poeciliidae): test of an ecomorphological paradigm. Biol J Linn Soc. 2008; 93(4):799-812.; Araújo et al., 2014Araújo MS, Perez SI, Magazoni MJC, Petry AC. Body size and allometric shape variation in the molly Poecilia vivipara along a gradient of salinity and predation. BMC Evol Biol. 2014; 14:251.), Poecilia reticulata Peters 1859 (Langerhans, DeWitt, 2004Langerhans RB, DeWitt TJ. Shared and unique features of evolutionary diversification. Am Nat. 2004; 164(3): 335-349.; Hendry et al., 2006Hendry AP, Kelly ML, Kinnison MT, Reznick DN. Parallel evolution of the sexes? Effects of predation and habitat features on the size and shape of wild guppies. J Evol Biol. 2006; 19(3):741-754., Burns et al., 2009Burns JG, Di Nardo P, Rood FH. The role of predation in variation in body shape in guppies Poecilia reticulata: a comparison of field and common garden phenotypes. J Fish Biol. 2009; 75(6):1144-1157.), Bryconops sp. cf. melanurus (Sidlauskas et al., 2006Sidlauskas B, Chernoff B, Machado-Allison A. Geographic and environmental variation in Bryconops sp.cf. melanurus (Ostariophysi: Characidae) from the Brazilian Pantanal. Ichthyol Res . 2006; 53(1):24-33.), Hyphessobrycon gr. heterorhabdus (García-Alzate et al., 2010García-Alzate CA, Román-Valencia C, González MI. Morfogeometría de los peces del género Hyphessobrycon (Characiformes: Characidae), grupo heterorhabdus, en Venezuela. Rev Biol Trop. 2010; 58(3):801-811.), Aspidoras albater Nijssen, Isbrücker 1976 (Secutti et al., 2011Secutti S, Reis RE, Trajano E. Differentiating cave Aspidoras catfish from a karst area of Central Brazil, upper rio Tocantins basin (Siluriformes: Callichthyidae). Neotrop Ichthyol . 2011; 9(4):689-695.), Cichla kelberi Kullander, Ferreira 2006 (Berbel-Filho et al., 2013Berbel-Filho WM, Jacobina UP, Martinez PA. Preservation effects in geometric morphometric approaches: freezing and alcohol in a freshwater fish. Ichthyol Res. 2013; 60(3):268-271.), Astyanax bimaculatus (Linnaeus 1758) (Santos, Araújo, 2015Santos ABI, Araújo FG. Evidence of morphological differences between Astyanax bimaculatus (Actinopterygii: Characidae) from reaches above and below dams on a tropical river. Environ Biol Fishes . 2015; 98(1):183-191.) and Brycon henni Eigenmann 1913 and Saccodon dariensis (Meek, Hildebrand 1913) (Restrepo-Escobar et al., 2016aRestrepo-Escobar N, Hurtado-Alarcón JC, Mancera-Rodríguez NJ, Márquez EJ. Variations of body geometry in Brycon henni (Teleostei: Characiformes, Bryconidae) in different rivers and streams. J Fish Biol . 2016a; 89(1):522-8.; 2016bRestrepo-Escobar N, Rangel-Medrano JD, Mancera-Rodríguez NJ, Márquez EJ. Molecular and morphometric characterization of two dental morphs of Saccodon dariensis (Pisces: Parodontidae). J Fish Biol . 2016b; 89(1):529-536.). Regarding solely Amazonian fishes, even fewer studies have examined morphological variation in body shape and size, e.g., Cox-Fernandes (1998Cox-Fernandes C. Sex-related morphological variation in two species of apteronotid fishes (Gymnotiformes) from the Amazon River Basin. Copeia. 1998; 1998(3):730-735.) on two apteronotid species, Sidlauskas et al. (2011Sidlauskas BL, Mol JH, Vari RP. Dealing with allometry in linear and geometric morphometrics: a taxonomic case study in the Leporinus cylindriformis group (Characiformes: Anostomidae) with description of a new species from Suriname. Zool J Linn Soc. 2011; 162(1):103-130.) on Leporinus cylindriformis group and Reiss, Grothues (2015Reiss P, Grothues TM, 2015. Geometric morphometric analysis of cyclical body shape changes in color pattern variants of Cichla temensis Humboldt, 1821 (Perciformes: Cichlidae) demonstrates reproductive energy allocation. Neotrop Ichthyol . 2013; 13(1):103-112.) on Cichla temensis.

Water bodies of the Amazon basin provide a variety of habitats at large (Goulding et al., 2003Goulding M, Barthem R, Ferreira E. Smithsonian Atlas of the Amazon. Washington: Smithsonian Books; 2003.) and local scales (Ferreira et al., 2007Ferreira E, Zuanon J, Forsberg B, Goulding M, Briglia-Ferreira SR. Rio Branco: peixes, ecologia e conservação de Roraima. Manaus: Amazon Conservation Association/INPA/Sociedade Civil Mamirauá; 2007.), and host the most diversified freshwater ichthyofauna in the world (Lowe-McConnell, 1999Lowe-McConnell RH. Estudos ecológicos de comunidades de peixes tropicais. Vazzoler AEAM, Agostinho AA, Cunningham PTM, tradutores. São Paulo: Edusp; 1999. (Coleção Base). Original title: Ecological studies in tropical fish communities.). A major portion of this diversity is composed of small-sized species inhabiting small floodplain rivers and streams, such as those found in the Negro River and tributaries. These species benefit from the annual flood pulse, which can range up to 13 m between the dry and wet seasons. These floods inundate large areas of rainforest (Goulding, 1997Goulding M. História natural dos rios amazônicos. Brasília: Sociedade Civil Mamirauá/CNPq/Rainforest Alliance; 1997.), providing shelter, food sources, and the possibility for population admixing for these so-called flooded-forest specialists (Piggot et al., 2011Piggot MP, Chao LN, Beheregaray LB. 2011. Three fishes in one: cryptic species in an Amazonian floodplain forest specialist. Biol J Linn Soc . 2011; 102(2):391-403.).

One species commonly found in floodplain areas is Hemigrammus coeruleus Durbin 1908, a small, ornamentally appealing characid, with a red lateral band, starting from the eye and ending at the caudal peduncle. This species has a maximum total length of 5.8 cm (Lima et al. 2003Lima FCT, Malabarba LR, Buckup PA, Pezzi da Silva JF, Vari RP, Harold A, Benine R, Oyakawa OT, Pavanelli CS, Menezes NA, Lucena CAS, Malabarba MCSL, Lucena ZMS, Reis RE, Langeani F, Cassati L, Bertaco VA, Moreira C, Lucinda PHF. Genera incertae sedis in Characidae. In: Reis RE, Kullander SO, Ferraris CJ, Jr., editors. Check list of the freshwater fishes of South and Central America. Porto Alegre: Edipucrs; 2003. p. 106-168.), and sexual dimorphism has been reported in old-age aquarium specimens (J. Zuanon, email, jzuanon3@gmail.com, September 2012). Although the species has also been found in the Trombetas and Nhamundá river basins (Reis, 2011Reis VCS. 2011. Relações entre o gradiente ambiental e a distribuição das assembléias de peixes em diferentes drenagens da Floresta Nacional Saracá-Taquera (PA). [MSc Dissertation] Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro; 2011.), over 600 Km downstream from the confluence of the Negro and Solimões rivers, the main databases on neotropical fishes define its occurrence area as the Solimões River and lower Negro River (Buckup et al., 2007Buckup PA, Menezes NA, Ghazzi MS, editores. Catálogo das espécies de peixes de água doce do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro; 2007. (Museu Nacional; Série Livros; 23).; Froese, Pauly, 2016Froese R, Pauly D, editors. FishBase. [World Wide Web electronic publication]. Penang (MA), Rome: FAO; 2016 [cited 2016 Aug 30]. Available from: Available from: http://fisbase.org

http://fisbase.org...

).

One of the main tributaries of the lower Negro River is the Unini River, a low-gradient black-water tributary that contains several large tributaries (sub-basins), in which H. coeruleus is common and widespread. Although most of these sub-basins are permanently black water and present similar environmental features, Solimõezinho River, the smallest tributary, exhibits seasonally muddy waters and differs from the other tributaries in some geomorphological features (Tab. 1). Either directly or indirectly, these differences may generate divergent selection pressures for fish populations in each sub-basin, and we could expect the specimens from this particular tributary to present distinct phenotypes. This scenario provides a good opportunity to study morphological variation within and among populations.

Overview of geomorphological and environmental features recorded in Unini River tributaries during time of specimen collections. Measurements including more than one value are expressed as the average and range.

Our work aimed to identify patterns of morphological variation in H. coeruleus from populations of the Unini River basin, and discuss potential processes that created them. Thus, we addressed the following questions: (1) Does morphology differ between the sexes? (2) Does body shape differ between populations of hydrologically connected areas? (3) Are there environmental differences between areas that could be related to the patterns of morphological variations found? This study represents one of the first to employ a population-level geometric morphometric approach to evaluate patterns of phenotypic variation within and among populations of fishes from dynamic Amazonian environments.

Material and Methods

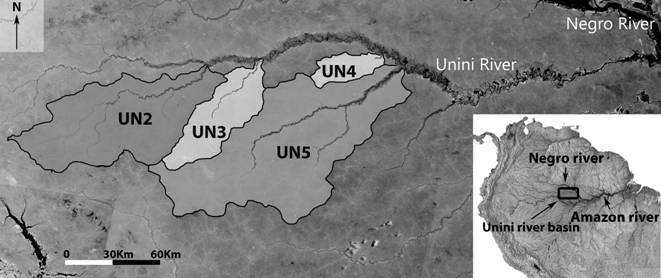

Study area. Amazonian blackwater rivers have their origin in Tertiary sandy-sediment terrain covered by pristine rainforest. Their waters are acidic, poor in nutrients and have a high concentration of dissolved humic acids (Sioli, 1985Sioli H. Amazônia, Fundamentos da ecologia da maior região de florestas tropicais. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes; 1985.). The Unini River is a low-gradient black-water tributary of the Negro River, located at 1°20’; 2°25’ S and 61°30’; 65° W, in central Amazonia, Amazonas State, Brazil (Fig. 1). Its basin lies within three major conservation units, the Amanã Sustainable Development Reserve (Amanã SDR), Jaú National Park (Jaú NP), and the Rio Unini Extractive Reserve (Rio Unini ER). Mean annual rainfall in the area is about 2,580 mm, with the annual floods causing river level variation of about 7 m between dry and rainy seasons (Almeida, 2014Almeida HL. Variações na história de vida de peixes na Reserva de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Amanã (AM) e suas implicações na morfologia e estruturação gênica das populações. [PhD Thesis] Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro; 2014.). Mean temperatures range from 26° to 26.7°C (DNPM, 1992DNPM - Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral. Normais climatológicas (1961-1990). Brasília: Departamento Nacional de Meteorologia; 1992.).

Map of Unini River basin in Central Brazilian Amazon indicating the location of the four tributaries sampled. UN2 - Preto River; UN3 - Arara River; UN4 - Solimõezinho River; UN5 - Pauini River.

Field sampling. Fish were collected from several localities in four tributaries (sub-basins) of the Unini River (Fig. 1), using hand nets and beach seines, on five occasions from August 2009 through November 2010. Shortly after collection, fish were anesthetized with clove oil and fixed in 10% formaldehyde. After 10-30 days, fish were preserved in 70% ethanol. Voucher specimens were deposited in the reference collection of Fish Ecology Lab, UFRJ, under the number DEPRJ 8372.

Sampling localities in the Preto River (UN2) were located at least 30 km upstream from its confluence with the upper Unini River. The Arara River (UN3) is located 60 km downstream from the Preto River, and fish sampling was performed at sites located at least 30 km upstream from the Arara River mouth. Moving downstream for an additional 90 km, is the Solimõezinho River (UN4), where sampling was performed from its mouth to sites 20 km upstream. The Pauini River (UN5) was the lowest sub-basin sampled. Fish were collected at least 40 km upstream from its confluence with the Unini River.

During the collection of specimens, water temperature, electrical conductivity, pH and dissolved oxygen were measured using a YSI 556 multiprobe system (Yellow Springs Instruments). Main stem width was measured in the field using a Garmin GPS 60CX and water colour was visually categorized into three types (black, clear and muddy). Solimõezinho River (UN4) was the only tributary with seasonally muddy waters (Tab. 1). Structural and geomorphological features for each sub-basin were also obtained from satellite images using softwares Google Earth and ArcMap version 10.1 (Esri Inc.). Sinuosity was calculated by dividing the total extension of the river’s main stem by the vectorial distance between the extremes of the main stem (Schumm, 1956Schumm, SA. Evolution of drainage systems and slopes in badlands at Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Geol Soc Am Bull. 1956; 67(5):597-646.). Environmental features are presented in Tab. 1.

Data collection. Geometric morphometric methods were used to estimate morphological variation for H. coeruleus. We measured the standard length of 121 adult specimens that were then placed on grid paper, and the left side of each was photographed using a GE X5 digital camera in macro mode. Coordinates were obtained by digitization of 11 anatomical landmarks using software TpsDig (Rohlf, 2004aRohlf FJ. TpsDig, Version 1.40. [Computer software - internet] Stony Brook, NY: Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York; 2004a. Available from http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/

http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/...

) in order to obtain the shape of each specimen. Landmarks were chosen based on previous studies with neotropical fishes (Langerhans, DeWitt, 2004Langerhans RB, Layman CA, Schrokollahi AM, DeWitt TJ. Predator-driven phenotypic diversification in Gambusia affinis. Evolution. 2004; 58(10):2305-2318.; Gomes-Jr., Monteiro, 2008Gomes-Jr JL, Monteiro LR. Morphological divergence patterns among populations of Poecilia vivipara (Teleostei; Poeciliidae): test of an ecomorphological paradigm. Biol J Linn Soc. 2008; 93(4):799-812.; García-Alzate et al., 2010García-Alzate CA, Román-Valencia C, González MI. Morfogeometría de los peces del género Hyphessobrycon (Characiformes: Characidae), grupo heterorhabdus, en Venezuela. Rev Biol Trop. 2010; 58(3):801-811.) and are shown in Fig. 2. We used the centroid size (the square root of the summed squared distances from each landmark to the configuration centroid, which is the average of all landmarks) as a body-size measurement in all analyses (Bookstein, 1991Bookstein FL. Morphometric tools for landmark data. Geometry and biology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1991.). The landmark configurations were superimposed by Procrustes fit (Rohlf, Slice, 1990Rohlf FJ, Slice D. Extensions of the Procrustes method for the optimal superimposition of landmarks. Syst Zool. 1990; 39(1):40-59.) using MorphoJ version 1.05f (Klingenberg, 2011Klingenberg CP. MorphoJ: an integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. Mol Ecol Resour. 2011; 11(2):353-357.) in order to obtain the shape of each specimen. This method removes the effect of size by placing the centroid of the specimens at the origin of the Cartesian System (0,0). Procrustes fit also adjusts the centroid size to one (1), and rotates the configuration until the sum of squares of the distance between corresponding landmarks is the lowest possible allowed for the estimation of a mean shape (Bookstein, 1991Bookstein FL. Morphometric tools for landmark data. Geometry and biology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1991.; Monteiro, Reis, 1999Monteiro LR, Reis SF. Princípios de morfometria geométrica. Ribeirão Preto: Editora Holos; 1999.; Zelditch et al., 2004Zelditch ML, Swiderski DL, Sheets HD Fink WL. Geometric morphometrics for biologists: a primer. New York and London: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004.).

Sketch of a Hemigrammus coeruleus individual indicating the 11 landmarks used in the morphological analyses. Landmarks were defined as follow: 1 - snout tip; 2 - dorsal insertion of pectoral fin; 3 - anterior insertion of pelvic fin; 4 - anterior insertion of anal fin; 5 - ventral insertion of caudal fin; 6 - dorsal insertion of caudal fin; 7 - anterior insertion of adipose fin; 8 - anterior insertion of dorsal fin; 9 - supra-occipital; 10 - endpoint of the opercle; 11 - central point of eye.

Data analysis. Morphological variation between the sexes was assessed by dissecting 72 previously photographed specimens (25 males, 47 females), including representatives from all sub-basins. The sex ratio of collected specimens was 1:1.88 (males/females); this does not differ from the reported sex ratio for the species in the Unini River (T. Barros et al., unpublished data). To test for differences in shape between the sexes, a MANOVA/Hotelling T-square was performed using the first seven principal component axes (which account for 82.46% of total variation) in R stats package (R Development Core Team, 2015R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Computer software - internet] Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. Available from: http://www.R-project.org/

http://www.R-project.org/...

). This was done using the principal components of a PCA that used the Procrustes coordinates generated in MorphoJ version 1.05f (Klingenberg, 2011Klingenberg CP. MorphoJ: an integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. Mol Ecol Resour. 2011; 11(2):353-357.). To test if there were differences in body size related to sex, a Student T test was performed using centroid size.

To analyze morphological divergence among the Unini River sub-basins (UN2, UN3, UN4 and UN5), we used a total of 92 adult specimens (> 20.9 mm SL), 23 from each tributary. Body-size differences among populations were assessed by one-way ANOVA. Significant differences between each population were determined by a post hoc Tukey test. Body-shape variation among sub-basins was assessed by submitting the matrix of shape variables to a canonical variate analysis (CVA), using MorphoJ. A discriminant function analysis (DFA) was performed to assess differences in shape among and within sub-basins, in R MASS package (Venables, Ripley, 2002Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern applied statistics with S, 4th ed. New York: Springer; 2002.). Differences in shape among populations were visualized through the grids of deformation generated by the software TPSRegr (Rohlf, 2004bRohlf FJ. TpsRegr, Version 1.38. [Computer software - internet] Stony Brook, NY: Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York ; 2004b. Available from http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/

http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/...

), using landmark coordinates and scores obtained from CVA. To evaluate the influence of ontogenetic allometry on shape variation, a linear regression analysis was performed in MorphoJ (Klingenberg, 2011Klingenberg CP. MorphoJ: an integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. Mol Ecol Resour. 2011; 11(2):353-357.). This regression included the Log of centroid size and the scores of principal components. All graphs were generated using the statistics program R (R Development Core Team, 2015R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Computer software - internet] Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. Available from: http://www.R-project.org/

http://www.R-project.org/...

).

Results

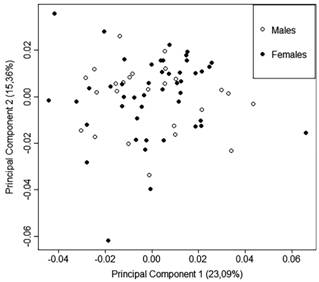

Fish used in the analysis for sexual dimorphism ranged from 20.4 mm to 40.2 mm SL. There was no evidence for morphological variation between the sexes (Fig. 3). The sexes do not differ statistically in the first seven principal components (accounting for 82.46% of total variation in body shape), as evidenced by MANOVA (Hotelling T2=0.036, P=0.934). Body size also did not differ between the sexes as indicated by the Student T test (P=0.55).

Scatterplot of principal components analysis examining differences in body shape, categorized by sex. There is no evidence of body-shape related to sexual dimorphism; N=72.

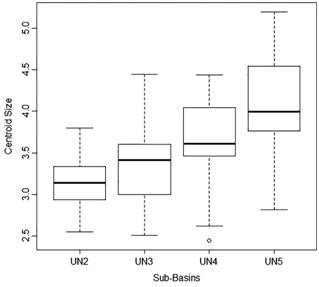

Fish used in the population analyses ranged from 20.9 mm to 40.2 mm SL. ANOVA revealed significant differences in body size among sites (F=12.23; P<0.0001). The largest body sizes were found in UN5, the lowermost sub-basin, and the smallest in UN2, the uppermost sub-basin (Fig. 4). Differences between populations are presented in Tab. 2.

Box-plot showing maximum, median, minimum values of centroid size of Hemigrammus coeruleus from four tributaries of Unini River. Quartiles correspond to 25% and 75% values. Tributaries are ordered from upstream to downstream.

Centroid size comparison among populations from four tributaries of the Unini River. P-Values shown are from Tukey post-hoc test (Error: Between MS=0.30610, df=88.000) of an ANOVA (F=12.23; P<0.0001). Significance is indicated with * and bold.

Samples were ordered by canonical variates, and the first two canonical axes depicted 81.66% of the variation among sub-basins. The results of the linear regression indicated that ontogenetic allometry accounted for only 10.88% of total variation, therefore, it was opted not to regress this variation out from the dataset. The first canonical axis (47.34%) ordinated the samples from UN4 with negative scores and samples from UN5 with positive scores. The majority of specimens from UN2 and UN3 samples presented intermediate scores. Body shape variation in the first axis was related to body depth and dorsal-fin position. Samples from UN5, with positive scores, showed more elongate bodies and dorsal fins located more posteriorly relative to samples from UN4, which exhibited negative scores (Fig. 5). The second canonical axis (34.31%) ordinated samples from UN4 and UN5 mostly with positive scores, UN3 with intermediate scores and UN2 with negative scores. The shape difference associated with the second axis was related to head size, the length of the caudal peduncle and position of the opercle endpoint. Samples from UN2 and UN3 showed a larger head, a longer caudal peduncle and a more ventrally positioned opercle than samples from UN4 and UN5 (Fig. 5). Although some degree of overlap between sub-basins was observed (especially between UN2 and UN3), two groups were strongly defined. Based on body shape, the discriminant analysis correctly classified 91.3% and 82.6% of specimens from UN4 and UN5, respectively (Tab. 3).

Axes of morphological variation for population data set. Ellipses indicate the 95% confidence interval for each population. Deformation grids represent positive and negative extremes of the observed shape variation associated with the first and second canonical axes; N=92.

Confusion matrix generated by Canonical Variate Analysis based on shape variables of populations of H. coeruleu s from four tributaries of Unini River.

Discussion

Differences in body morphology can be used to detect local adaptation among populations (Marques et al., 2016Marques DA, Lucek K, Meier JI, Mwaiko S, Wagner CE, Excoffier L, Seehausen O. Genomics of rapid incipient speciation in sympatric threespine stickleback. Plos Genet 2016; 12(2):e1005887.). However, within populations there can be variation due to sexual maturity (Reiss, Grothues, 2015Reiss P, Grothues TM, 2015. Geometric morphometric analysis of cyclical body shape changes in color pattern variants of Cichla temensis Humboldt, 1821 (Perciformes: Cichlidae) demonstrates reproductive energy allocation. Neotrop Ichthyol . 2013; 13(1):103-112.) and sexual dimorphism (Gomes-Jr., Monteiro, 2008Gomes-Jr JL, Monteiro LR. Morphological divergence patterns among populations of Poecilia vivipara (Teleostei; Poeciliidae): test of an ecomorphological paradigm. Biol J Linn Soc. 2008; 93(4):799-812.). Thus, we investigated morphological divergence related to sexual dimorphism prior to assessing population divergence. Within the Characidae, sexually dimorphic characters have been reported in several species. Most dimorphic characters are associated with sexual structures, such as the presence of hooks in anal and pelvic fins (Menezes et al., 2009Menezes NA, Weitzman SH. Systematics of the Neotropical fish subfamily Glandulocaudinae (Teleostei: Characiformes: Characidae). Neotrop Ichthyol . 2009; 7(3):295-370.; Dala-Corte, Fialho, 2014Dala-Corte RB, Fialho CB. Reproductive tactics and development of sexually dimorphic structures in a stream-dwelling characid fish (Deuterodon stigmaturus) from Atlantic Forest. Environ Biol Fishes; 2014; 97(10):1119-1127.), sexual glands (Menezes, Weitzman, 2009Menezes NA, Weitzman SH. Systematics of the Neotropical fish subfamily Glandulocaudinae (Teleostei: Characiformes: Characidae). Neotrop Ichthyol . 2009; 7(3):295-370.; Menezes et al., 2009Menezes NA, Netto-Ferreira AL, Ferreira KM. A new species of Bryconadenos (Characiformes: Characidae) from the rio Curuá (rio Xingu drainage), Brazil. Neotrop Ichthyol. 2009; 7(2):147-152.), or even fin shape (Menezes et al., 2009Menezes NA, Netto-Ferreira AL, Ferreira KM. A new species of Bryconadenos (Characiformes: Characidae) from the rio Curuá (rio Xingu drainage), Brazil. Neotrop Ichthyol. 2009; 7(2):147-152.), but body shape (Ortega-Lara et al., 2002Ortega-Lara A, Aguiño A, Sánchez GC. 2002. Caracterización de la ictiofauna nativa de los principales ríos de la cuenca alta del río Cauca en el departamento de Cauca. Informe presentado a la Corporación Autónoma Regional del Cauca, CRC. Popayán: Fundación para la Investigación y el Desarollo Sostenible, Funindes. 2002.; Riehl, Baensch, 2007Riehl R, Baensch HA. Aquarium Atlas Vol.1. 7th ed. Mergus-Verlag Publishers; 2007.) and body size (Mazzoni et al., 2005Mazzoni R, Mendonça RS, Caramaschi EP. Reproductive biology of Astyanax janeiroensis (Osteichthyes, Characidae) from the Ubatiba River, Maricá, RJ, Brazil. Braz J Biol. 2005; 65(4):643-649.; Mazzoni, Petito, 1999Mazzoni R, Petito JT. Reproductive biology of a Tetragonopterinae (Osteichthyes, Characidae) of the Ubatiba fluvial system, Maricá - RJ. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 1999; 42(4):455-461.) have also been reported to differ. For H. coeruleus, aquarium observations of old-age individuals (approximately 7 cm SL) indicate differences between males and females (J. Zuanon, email communication, jzuanon3@gmail.com, September 2012) related to body colour, and fin length and colour, which are not possible to detect with the landmarks used here, and in shape and size (females slightly bigger and slender). However, in the populations of H. coeruleus studied herein (largest individuals around 4 cm SL) there were no differences between the sexes in size and shape. Mortality rates in natural habitats differ dramatically from artificial environments, and individuals appear unlikely to survive long enough in the wild to reach large sizes (T. Barros et al. unpublished data), when sex differences in body shape could become apparent.

Despite limiting our analyses to only mature adult specimens we found size differences among populations. The uppermost sub-basins (UN2 and UN3) contained small-sized individuals while the largest individuals were collected in UN5 (the lowermost sampled). Since it has been shown that body and head shape change during the course of fish growth, there was some concern that phenotypic divergence was a product of differences in size between populations. Thus, we tested for differences associated with allometric growth among populations, but this accounted for only 10.88% of all variation.

Since population divergence was found to be little influenced by the size of individuals or sexual dimorphism (intrinsic factors), we believe that divergent environmental pressures acting in the Unini River tributaries are the likely cause of phenotypic differences. Even with a high degree of overlap between populations from UN2 and UN3, due to high morphological variation within each group, the analyses using landmark coordinates were able to detect morphological differences among populations resulting in significant groups corresponding to each sub-basin. Specimens from UN4 and UN5 differed from the other populations, evidenced by the two strong goups formed in the CVA, with the Solimõezinho (UN4) distinctly diverging from the continuous formed by UN2 and UN3. This pattern suggests that, in addition to two groups, there is a gradient of variation in body shape, which is expected in populations that are not isolated, such as those evaluated here. The morphological distinctiveness of the UN4 population could be due to the unique physical characteristics of this river and / or differences in predation pressure. Below we discuss these possibilities.

We found major differences in geomorphological descriptors among tributaries. These could directly or indirectly influence ecological conditions experienced by fish populations. The Solimõezinho River (UN4) exhibited, by far, the fewest lakes and narrowest floodplain. Composition of ichthyofauna is highly influenced by water flow, type of environment and habitat structure (Lowe-McConnell, 1999Lowe-McConnell RH. Estudos ecológicos de comunidades de peixes tropicais. Vazzoler AEAM, Agostinho AA, Cunningham PTM, tradutores. São Paulo: Edusp; 1999. (Coleção Base). Original title: Ecological studies in tropical fish communities.). Minor differences were found in physical and chemical features between the sub-basins; however, only the Solimõezinho River (UN4) had muddy waters. This feature apparently did not result in changes in the chemical properties of the water, as could be expected (usually, the more particulate matter carried, the higher the electrical conductivity and pH). However, it might play an important role in visually oriented predator avoidance and foraging behaviour (Rodríguez, Lewis, 1997Rodríguez MA, Lewis-Jr WM. Structure of fish assemblages along environmental gradients in floodplain lakes of the Orinoco River. Ecol Monogr. 1997; 67(1):109-128.), since transparency drops to only a few centimetres (compared to ≥ 1.4 m in the sediment-free black-water rivers). Evidence for morphological divergences due primarily to water transparency have been reported in other studies, such as Bartels et al. (2012Bartels P, Hirsch PE, Svanbäck R, Eklöv P. Water transparency drives intra-population divergence in Eurasian perch (Perca fluviatilis). PloS ONE. 2012; 7(8):e43641.) for populations of Perca fluviatilis.

Predation has received much attention in morphometric studies of freshwater fishes both in nature and in the laboratory, where it has been shown to act as an important selective pressure on body shape (Langerhans et al., 2004Langerhans RB, Layman CA, Schrokollahi AM, DeWitt TJ. Predator-driven phenotypic diversification in Gambusia affinis. Evolution. 2004; 58(10):2305-2318.; Gomes-Jr., Monteiro, 2008Gomes-Jr JL, Monteiro LR. Morphological divergence patterns among populations of Poecilia vivipara (Teleostei; Poeciliidae): test of an ecomorphological paradigm. Biol J Linn Soc. 2008; 93(4):799-812.; Burns et al., 2009Burns JG, Di Nardo P, Rood FH. The role of predation in variation in body shape in guppies Poecilia reticulata: a comparison of field and common garden phenotypes. J Fish Biol. 2009; 75(6):1144-1157.; Webster et al., 2011Webster MM, Atton N, Hart PJB, Ward AJW. Habitat-specific morphological variation among threespine sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus) within a drainage basin. PloS ONE . 2011; 6(6):e21060.; van Rijssel, Witte, 2013van Rijssel JC, Witte F. Adaptive responses in resurgent Lake Victoria cichlids over the past 30 years. Evol Ecol. 2013; 27(2):253-267., Araújo et al., 2014Araújo MS, Perez SI, Magazoni MJC, Petry AC. Body size and allometric shape variation in the molly Poecilia vivipara along a gradient of salinity and predation. BMC Evol Biol. 2014; 14:251.). Elongate bodies, such as those from UN2, UN3 and UN5, are often associated with steady-swimming and relatively good swimming performance (Langerhans, Reznick, 2010Langerhans RB, Reznick D. Ecology and evolution of swimming performances in fishes: predicting evolution with biomechanics. In: Domenici P, Kapoor BG, editors. Fish locomotion: an etho-ecological perspective. Enfield: Science Publishers; 2010. p. 200-248.). Langerhans et al. (2003Langerhans RB, Layman CA, Langerhans AK, DeWitt TJ. Habitat-associated morphological divergence in two Neotropical fish species. Biol J Linn Soc . 2003; 80(4):689-698.) compared specimens of the cichlid B. wawrini and the characid B. caudomaculatus from lakes and rivers and showed that in lotic environments swimming performance is positively correlated with more elongate bodies. However, it was not possible for us to test for such a correlation. Additionally, elongate bodies are predicted to improve the ability to escape from pursuit predators (Langerhans, Reznick, 2009Langerhans RB, Reznick D. Ecology and evolution of swimming performances in fishes: predicting evolution with biomechanics. In: Domenici P, Kapoor BG, editors. Fish locomotion: an etho-ecological perspective. Enfield: Science Publishers; 2010. p. 200-248.). Conversely, deeper bodies, as the ones found in UN4, can misdirect a predator strike away from the optimal capture point, decreasing prey vulnerability in short strikes (Webb, 1986Webb PW. Effect of body form and response threshold on the vulnerability of four species of teleost prey attacked by largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1986; 43(4):763-771.). In low-transparency conditions, pursuit foraging behaviour by visually oriented predators could be limited to very short distances or to ambush strikes only. Elongate bodies (as in UN2, UN3 and UN5) would not bring additional advantages under these conditions. Potential short-distance pursuit predators such as Cichla species, highly abundant in most of the Unini River and its tributaries, including UN2, UN3 and UN5, were not recorded in the Solimõezinho River (UN4) (H. Lazzarotto, unpublished data), which suggests their absence or very low abundance in this tributary.

In addition to predation, local habitat has been found to influence body shape divergence in other small characids (e.g., Langerhans et al., 2003Langerhans RB, Layman CA, Langerhans AK, DeWitt TJ. Habitat-associated morphological divergence in two Neotropical fish species. Biol J Linn Soc . 2003; 80(4):689-698.; Sidlauskas et al., 2006Sidlauskas B, Chernoff B, Machado-Allison A. Geographic and environmental variation in Bryconops sp.cf. melanurus (Ostariophysi: Characidae) from the Brazilian Pantanal. Ichthyol Res . 2006; 53(1):24-33.). The variation in body shape of H. coeruleus in the most divergent tributary (UN4) could also be a result of local specialization to its unique habitat features. This result meets the predictions that the population with the most distinct morphology should come from the tributary with the most divergent environmental conditions.

Langerhans (2008Langerhans RB. 2008. Predictability of phenotypic differentiation across flow regimes in fishes. Integr Comp Biol. 2008; 48: 750-768.), studying phenotypic patterns between flow regimes, indicated that, on the intraspecific scale, both genetic divergence and phenotypic plasticity play important roles in phenotypic differentiation. Although genetic diversification is possible with gene flow (e.g., Gaither et al., 2015Gaither MR, Bernal MA, Coleman RR, Bowen BW, Jones SA, Simison WB, Rocha LA. Genomic signatures of geographic isolation and natural selection in coral reef fishes. Mol Ecol. 2015; 24(7):1543-1557.; Marques et al., 2016Marques DA, Lucek K, Meier JI, Mwaiko S, Wagner CE, Excoffier L, Seehausen O. Genomics of rapid incipient speciation in sympatric threespine stickleback. Plos Genet 2016; 12(2):e1005887.), structuring due to ecological selection or genetic drift is more likely under reproductive isolation (Rundle, Nosil, 2005Rundle HD, Nosil P. Ecological speciation. Ecol Lett. 2005; 8(3):336-352.). The current study uses specimens from distant localities, but a few individuals of H. coeruleus were also observed and collected in sites between tributaries located on the Unini River main stem. This suggests that the species is distributed along the entire length of the river, which would enable gene flow and individual mixing between tributaries. Furthermore, in Amazonian rivers, major environmental variation occurs seasonally when water temperature, conductivity, transparency, habitat structure and fish densities (influencing the degree of predation pressure) dramatically change (Sioli, 1985Sioli H. Amazônia, Fundamentos da ecologia da maior região de florestas tropicais. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes; 1985.). This set of seasonally predictable conditions, that impose a major influence on the life-cycle of fishes by creating heterogeneous conditions, greatly extending suitable habitat, and facilitating gene flow and individual movement throughout the flooded forest (Piggot et al., 2011Piggot MP, Chao LN, Beheregaray LB. 2011. Three fishes in one: cryptic species in an Amazonian floodplain forest specialist. Biol J Linn Soc . 2011; 102(2):391-403.), should theoretically favor plasticity over local specialization (Sultan, Spencer, 2002Sultan SE, Spencer HG. Metapopulation structure favors plasticity over local adaptation. Am Nat . 2002; 160(2):271-283.; Schlichting, Smith, 2002Schlichting CD, Smith H. Phenotypic plasticity: linking molecular mechanisms with evolutionary outcomes. Evol Ecol . 2002; 16(3):189-211.). Our results, however, cannot determine whether the observed differences in shape among populations is due to phenotypic plasticity, genetic differentiation, or a combination of both. Future studies using a common garden experimental approach could determine whether observed morphological differences among populations have a genetic basis. Likewise, future molecular work in H. coeruleus could assess genetic differentiation, gene flow, and population interconnectedness.

Our morphometrics approach was able to distinguish subtle differences in body morphology among populations of H. coreuleus related to environmental differences. The replication of a similar approach in other fish species, either from the Unini River basin or from the Amazon, could help elucidate general patterns of phenotypic variation in seasonal environments. Furthermore, although yet to be tested in this way, this powerful tool could be useful in detecting recent conditions that populations were subjected to, such as environmental impacts.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Jansen Zuanon and Eurizangela Dary for the providing support at INPA during the planning of the expeditions, identification of the species collected, and by providing information about aquarium specimens. Special thanks to the staff of Rio Unini ER and Jaú NP (ICMBio) for the support with field facilities. We thank Afonso Neto, Antonio Cordeiro, Everson Soares, Francinei Oliveira, Francisco Nunes Filho, Frank Jhones Andrade, Gabriel Cardoso, Mariano Andrade and Sandro Brito for helping collect specimens in the Unini River basin, and to several students from the UFRJ Fish Ecology Lab. We appreciate the constructive criticism of Dr. Brian Sidlauskas, from which the current paper benefited. We are also grateful to Janet Reid, David Catania and Dr. Andrew Furness, who revised the English version of the manuscript. H.L. received a doctoral fellowship by CNPq through Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia (PPGE-UFRJ) and further support from the Programa Nacional de Cooperação Acadêmica (PROCAD - CAPES), in a partnership between PPGE-UFRJ and Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia de Água Doce e Pesca Interior (BADPI-INPA). Field excursions were conducted by the Instituto de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Mamirauá financed by the Projeto Corredores Ecológicos (Brazilian Ministry of the Environment - MMA), with funding from the German government through KfW. Fish were collected under IBAMA licenses # 14666-1 and 22402-1.

References

- Almeida HL. Variações na história de vida de peixes na Reserva de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Amanã (AM) e suas implicações na morfologia e estruturação gênica das populações. [PhD Thesis] Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro; 2014.

- Araújo MS, Perez SI, Magazoni MJC, Petry AC. Body size and allometric shape variation in the molly Poecilia vivipara along a gradient of salinity and predation. BMC Evol Biol. 2014; 14:251.

- Bartels P, Hirsch PE, Svanbäck R, Eklöv P. Water transparency drives intra-population divergence in Eurasian perch (Perca fluviatilis). PloS ONE. 2012; 7(8):e43641.

- Berbel-Filho WM, Jacobina UP, Martinez PA. Preservation effects in geometric morphometric approaches: freezing and alcohol in a freshwater fish. Ichthyol Res. 2013; 60(3):268-271.

- Bernatchez L. Ecological theory of adaptive radiation: an empirical assessment from coregonine fishes (Salmoniformes). In Hendry AP, Stearns SC, editors. Evolution illuminated: salmon and their relatives. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. p 175-207.

- Bookstein FL. Morphometric tools for landmark data. Geometry and biology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1991.

- Buckup PA, Menezes NA, Ghazzi MS, editores. Catálogo das espécies de peixes de água doce do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro; 2007. (Museu Nacional; Série Livros; 23).

- Burns JG, Di Nardo P, Rood FH. The role of predation in variation in body shape in guppies Poecilia reticulata: a comparison of field and common garden phenotypes. J Fish Biol. 2009; 75(6):1144-1157.

- Cox-Fernandes C. Sex-related morphological variation in two species of apteronotid fishes (Gymnotiformes) from the Amazon River Basin. Copeia. 1998; 1998(3):730-735.

- Dala-Corte RB, Fialho CB. Reproductive tactics and development of sexually dimorphic structures in a stream-dwelling characid fish (Deuterodon stigmaturus) from Atlantic Forest. Environ Biol Fishes; 2014; 97(10):1119-1127.

- DNPM - Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral. Normais climatológicas (1961-1990). Brasília: Departamento Nacional de Meteorologia; 1992.

- Ferreira E, Zuanon J, Forsberg B, Goulding M, Briglia-Ferreira SR. Rio Branco: peixes, ecologia e conservação de Roraima. Manaus: Amazon Conservation Association/INPA/Sociedade Civil Mamirauá; 2007.

- Froese R, Pauly D, editors. FishBase. [World Wide Web electronic publication]. Penang (MA), Rome: FAO; 2016 [cited 2016 Aug 30]. Available from: Available from: http://fisbase.org

» http://fisbase.org - Gaither MR, Bernal MA, Coleman RR, Bowen BW, Jones SA, Simison WB, Rocha LA. Genomic signatures of geographic isolation and natural selection in coral reef fishes. Mol Ecol. 2015; 24(7):1543-1557.

- García-Alzate CA, Román-Valencia C, González MI. Morfogeometría de los peces del género Hyphessobrycon (Characiformes: Characidae), grupo heterorhabdus, en Venezuela. Rev Biol Trop. 2010; 58(3):801-811.

- Gomes-Jr JL, Monteiro LR. Morphological divergence patterns among populations of Poecilia vivipara (Teleostei; Poeciliidae): test of an ecomorphological paradigm. Biol J Linn Soc. 2008; 93(4):799-812.

- Goulding M. História natural dos rios amazônicos. Brasília: Sociedade Civil Mamirauá/CNPq/Rainforest Alliance; 1997.

- Goulding M, Barthem R, Ferreira E. Smithsonian Atlas of the Amazon. Washington: Smithsonian Books; 2003.

- Hendry AP, Kelly ML, Kinnison MT, Reznick DN. Parallel evolution of the sexes? Effects of predation and habitat features on the size and shape of wild guppies. J Evol Biol. 2006; 19(3):741-754.

- Kitano J, Mori S, Peichel CL. Sexual dimorphism in the external morphology of the threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus). Copeia . 2007; 2007(2):336-349.

- Klingenberg CP. MorphoJ: an integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. Mol Ecol Resour. 2011; 11(2):353-357.

- Langerhans RB. 2008. Predictability of phenotypic differentiation across flow regimes in fishes. Integr Comp Biol. 2008; 48: 750-768.

- Langerhans RB, DeWitt TJ. Shared and unique features of evolutionary diversification. Am Nat. 2004; 164(3): 335-349.

- Langerhans RB, Layman CA, Langerhans AK, DeWitt TJ. Habitat-associated morphological divergence in two Neotropical fish species. Biol J Linn Soc . 2003; 80(4):689-698.

- Langerhans RB, Layman CA, Schrokollahi AM, DeWitt TJ. Predator-driven phenotypic diversification in Gambusia affinis Evolution. 2004; 58(10):2305-2318.

- Langerhans RB, Reznick D. Ecology and evolution of swimming performances in fishes: predicting evolution with biomechanics. In: Domenici P, Kapoor BG, editors. Fish locomotion: an etho-ecological perspective. Enfield: Science Publishers; 2010. p. 200-248.

- Lima FCT, Malabarba LR, Buckup PA, Pezzi da Silva JF, Vari RP, Harold A, Benine R, Oyakawa OT, Pavanelli CS, Menezes NA, Lucena CAS, Malabarba MCSL, Lucena ZMS, Reis RE, Langeani F, Cassati L, Bertaco VA, Moreira C, Lucinda PHF. Genera incertae sedis in Characidae. In: Reis RE, Kullander SO, Ferraris CJ, Jr., editors. Check list of the freshwater fishes of South and Central America. Porto Alegre: Edipucrs; 2003. p. 106-168.

- Lowe-McConnell RH. Estudos ecológicos de comunidades de peixes tropicais. Vazzoler AEAM, Agostinho AA, Cunningham PTM, tradutores. São Paulo: Edusp; 1999. (Coleção Base). Original title: Ecological studies in tropical fish communities.

- Marques DA, Lucek K, Meier JI, Mwaiko S, Wagner CE, Excoffier L, Seehausen O. Genomics of rapid incipient speciation in sympatric threespine stickleback. Plos Genet 2016; 12(2):e1005887.

- Mazzoni R, Petito JT. Reproductive biology of a Tetragonopterinae (Osteichthyes, Characidae) of the Ubatiba fluvial system, Maricá - RJ. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 1999; 42(4):455-461.

- Mazzoni R, Mendonça RS, Caramaschi EP. Reproductive biology of Astyanax janeiroensis (Osteichthyes, Characidae) from the Ubatiba River, Maricá, RJ, Brazil. Braz J Biol. 2005; 65(4):643-649.

- Menezes NA, Netto-Ferreira AL, Ferreira KM. A new species of Bryconadenos (Characiformes: Characidae) from the rio Curuá (rio Xingu drainage), Brazil. Neotrop Ichthyol. 2009; 7(2):147-152.

- Menezes NA, Weitzman SH. Systematics of the Neotropical fish subfamily Glandulocaudinae (Teleostei: Characiformes: Characidae). Neotrop Ichthyol . 2009; 7(3):295-370.

- Monteiro LM, Gomes-Jr. JL. Morphological divergence rates test for natural selection: uncertainty of parameter estimation and robustness of results. Genet Mol Biol. 2005; 28(2):345-355.

- Monteiro LR, Reis SF. Princípios de morfometria geométrica. Ribeirão Preto: Editora Holos; 1999.

- Neves FM, Monteiro LR. Body shape and size divergence among populations of Poecilia vivipara in coastal lagoons of south-eastern Brazil. J Fish Biol . 2003; 63(4):928-941.

- Ortega-Lara A, Aguiño A, Sánchez GC. 2002. Caracterización de la ictiofauna nativa de los principales ríos de la cuenca alta del río Cauca en el departamento de Cauca. Informe presentado a la Corporación Autónoma Regional del Cauca, CRC. Popayán: Fundación para la Investigación y el Desarollo Sostenible, Funindes. 2002.

- Piggot MP, Chao LN, Beheregaray LB. 2011. Three fishes in one: cryptic species in an Amazonian floodplain forest specialist. Biol J Linn Soc . 2011; 102(2):391-403.

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Computer software - internet] Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. Available from: http://www.R-project.org/

» http://www.R-project.org/ - Reis VCS. 2011. Relações entre o gradiente ambiental e a distribuição das assembléias de peixes em diferentes drenagens da Floresta Nacional Saracá-Taquera (PA). [MSc Dissertation] Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro; 2011.

- Reiss P, Grothues TM, 2015. Geometric morphometric analysis of cyclical body shape changes in color pattern variants of Cichla temensis Humboldt, 1821 (Perciformes: Cichlidae) demonstrates reproductive energy allocation. Neotrop Ichthyol . 2013; 13(1):103-112.

- Restrepo-Escobar N, Hurtado-Alarcón JC, Mancera-Rodríguez NJ, Márquez EJ. Variations of body geometry in Brycon henni (Teleostei: Characiformes, Bryconidae) in different rivers and streams. J Fish Biol . 2016a; 89(1):522-8.

- Restrepo-Escobar N, Rangel-Medrano JD, Mancera-Rodríguez NJ, Márquez EJ. Molecular and morphometric characterization of two dental morphs of Saccodon dariensis (Pisces: Parodontidae). J Fish Biol . 2016b; 89(1):529-536.

- Riehl R, Baensch HA. Aquarium Atlas Vol.1. 7th ed. Mergus-Verlag Publishers; 2007.

- van Rijssel JC, Witte F. Adaptive responses in resurgent Lake Victoria cichlids over the past 30 years. Evol Ecol. 2013; 27(2):253-267.

- Rodríguez MA, Lewis-Jr WM. Structure of fish assemblages along environmental gradients in floodplain lakes of the Orinoco River. Ecol Monogr. 1997; 67(1):109-128.

- Rohlf FJ, Slice D. Extensions of the Procrustes method for the optimal superimposition of landmarks. Syst Zool. 1990; 39(1):40-59.

- Rohlf FJ. TpsDig, Version 1.40. [Computer software - internet] Stony Brook, NY: Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York; 2004a. Available from http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/

» http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/ - Rohlf FJ. TpsRegr, Version 1.38. [Computer software - internet] Stony Brook, NY: Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York ; 2004b. Available from http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/

» http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/ - Rundle HD, Nosil P. Ecological speciation. Ecol Lett. 2005; 8(3):336-352.

- Santos ABI, Araújo FG. Evidence of morphological differences between Astyanax bimaculatus (Actinopterygii: Characidae) from reaches above and below dams on a tropical river. Environ Biol Fishes . 2015; 98(1):183-191.

- Schlichting CD, Smith H. Phenotypic plasticity: linking molecular mechanisms with evolutionary outcomes. Evol Ecol . 2002; 16(3):189-211.

- Schumm, SA. Evolution of drainage systems and slopes in badlands at Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Geol Soc Am Bull. 1956; 67(5):597-646.

- Secutti S, Reis RE, Trajano E. Differentiating cave Aspidoras catfish from a karst area of Central Brazil, upper rio Tocantins basin (Siluriformes: Callichthyidae). Neotrop Ichthyol . 2011; 9(4):689-695.

- Sidlauskas B, Chernoff B, Machado-Allison A. Geographic and environmental variation in Bryconops sp.cf. melanurus (Ostariophysi: Characidae) from the Brazilian Pantanal. Ichthyol Res . 2006; 53(1):24-33.

- Sidlauskas BL, Mol JH, Vari RP. Dealing with allometry in linear and geometric morphometrics: a taxonomic case study in the Leporinus cylindriformis group (Characiformes: Anostomidae) with description of a new species from Suriname. Zool J Linn Soc. 2011; 162(1):103-130.

- Sioli H. Amazônia, Fundamentos da ecologia da maior região de florestas tropicais. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes; 1985.

- Sultan SE, Spencer HG. Metapopulation structure favors plasticity over local adaptation. Am Nat . 2002; 160(2):271-283.

- Trapani J. Geometric morphometric analysis of body-form variability in Cichlasoma minckleyi, the Cuatro Cienegas cichlid. Environ Biol Fishes . 2003; 68(4):357-369.

- Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern applied statistics with S, 4th ed. New York: Springer; 2002.

- Wagner CE, McIntyre PB, Buels KS, Gilbert DM, Michel E. Diet predicts intestine length in Tanganyika’s cichlid fishes. Funct Ecol. 2009; 23(6):1122-1131.

- Webb PW. Effect of body form and response threshold on the vulnerability of four species of teleost prey attacked by largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1986; 43(4):763-771.

- Webster MM, Atton N, Hart PJB, Ward AJW. Habitat-specific morphological variation among threespine sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus) within a drainage basin. PloS ONE . 2011; 6(6):e21060.

- Zelditch ML, Swiderski DL, Sheets HD Fink WL. Geometric morphometrics for biologists: a primer. New York and London: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004.

Data availability

Data citations

Froese R, Pauly D, editors. FishBase. [World Wide Web electronic publication]. Penang (MA), Rome: FAO; 2016 [cited 2016 Aug 30]. Available from: Available from: http://fisbase.org

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

2017

History

-

Received

09 Sept 2014 -

Accepted

18 Jan 2017