Abstracts

This essay analyzes discourses and narratives of men who frequent the washrooms at public venues in Havana. The graffiti on toilet room walls works as an articulator of micro markets of sexual communication and gender/sexual relations. In this article graffiti is the focus of an ethnographic approach to everyday life and discourses on homoeroticism at play in those sites. The final part of the essay moves on from graffiti in public toilets to chart other places constituting a homoerotic ambiente in Havana.

Havana; homoerotic ambient; sexual graffiti; public washrooms

Este artigo analisa, em uma perspectiva de gênero, discursos e narrativas de homens que frequentam banheiros públicos em Havana em busca de encontros sexuais. O grafiti nas paredes atua como articulador da comunicação sexual e das relações de gênero nessas redes e serve de ponto de entrada para a observação etnográfica. A parte final do texto mapeia outros pontos do circuito do ambiente homossexual habanero.

Havana; homoerotismo; sociabilidade; grafiti; banheiros públicos

Este artículo analiza, en una perspectiva de género, discursos y narrativas de varones que frecuentan baños públicos en La Habana en busca de encuentros sexuales. El grafiti en las paredes actúa como articulador de la comunicación sexual y las relaciones de género en esas redes y sirve de punto de entrada para la observación etnográfica. La parte final del texto mapea otros puntos del circuito del ambiente homosexual habanero.

La Habana; homoerotismo; sociabilidad; grafiti; baños públicos

ARTICLE

Walls talk. Homoerotic networks and sexual graffiti in public washrooms in Havana

Paredes que hablan. Redes homoeróticas y grafiti sexual en baños públicos de La Habana

Paredes que falam. Redes homoeróticas e grafiti sexual em banheiros públicos de Havana

Abel Sierra Madero

PhD in History University of Havana Cuban Union of Writers and Artists (UNEAC) - Havana, Cuba > sierramadero@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

This essay analyzes discourses and narratives of men who frequent the washrooms at public venues in Havana. The graffiti on toilet room walls works as an articulator of micro markets of sexual communication and gender/sexual relations. In this article graffiti is the focus of an ethnographic approach to everyday life and discourses on homoeroticism at play in those sites. The final part of the essay moves on from graffiti in public toilets to chart other places constituting a homoerotic ambiente in Havana.

Key words: Havana; homoerotic ambient: sexual graffiti; public washrooms

RESUMEN

Este artículo analiza, en una perspectiva de género, discursos y narrativas de varones que frecuentan baños públicos en La Habana en busca de encuentros sexuales. El grafiti en las paredes actúa como articulador de la comunicación sexual y las relaciones de género en esas redes y sirve de punto de entrada para la observación etnográfica. La parte final del texto mapea otros puntos del circuito del ambiente homosexual habanero.

Palabras clave: La Habana; homoerotismo; sociabilidad; grafiti; baños públicos

RESUMO

Este artigo analisa, em uma perspectiva de gênero, discursos e narrativas de homens que frequentam banheiros públicos em Havana em busca de encontros sexuais. O grafiti nas paredes atua como articulador da comunicação sexual e das relações de gênero nessas redes e serve de ponto de entrada para a observação etnográfica. A parte final do texto mapeia outros pontos do circuito do ambiente homossexual habanero.

Palavras-chave: Havana; homoerotismo; sociabilidade; grafiti; banheiros públicos

Introduction

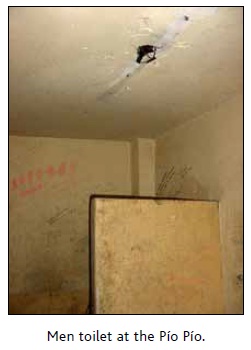

This article originated from an irrepressible and mundane physiological call of a city stroller after having a couple of beers in a joint in Havana’s El Vedado quarter during a gray September afternoon. I was near L and 17th streets and desperate to relieve my bladder. Suddenly, I caught sight of a massive old lady posted at a hallway, nodding her drowsy head and balancing a plastic plate with some loose change on her voluminous lap. The cash plate was a clear indicator that I was in the proximity of a public toilet. It was located in a once popular Havana eatery in the 1980s, specialized on fast chicken, bearing the metonymic name of "Pío Pío" ("Cheep Cheep").

As I rushed to the toilet, the brisk roaring voice of the old lady stopped me short to announce that it was occupied. After 15 minutes of restless pacing, the washroom sentinel realized my anxiety and in a fit of anger began belching out obscenities at the washroom patrons who, upon hearing her hollered threats to call the police, came out the door in a panicky stampede. The three individuals hastily walked passed me, heads down, but bearing in their eyes the fraternal complicity of a "secret" shared in the four walls of that washroom. I immediately decided to unravel the mystery, although it was a little too obvious to infer.

The place had a little grimy window, no light and excreted a sickly, suffocating, sweet stench - a mix of sulphur, methane, semen, sweat and furtive, anonymous sex. The odors were like a "territorial mark" left behind by urban "tropical animals." The chaotically scribbled-on wallstranstextual manuscripts on concrete,revealed the imprint of an anonymous and clandestine communion of writers engaged in a flow of words, simultaneously public and private, sexual and marginal scriptural practice in a urban milieu that ignores its producers. Attracted to each other by physical contact, this open community of writers and speakersso familiar with the comings and goings of passersbyof various professions, social classes and groups, unearthed a series of conflicting identities and sociability models. .

Underneath each drawing and word, numerous other fragmented pieces of narratives and life stories had rallied, day after day, populating the walls with shared codes that turned a physiological discharge into a space of convergence, of unions and disunions, of socialization, of rituals, and political debate on sexual issues and sexual exchanges. Countless individuals turned the washroomas Marc Augé put itinto an "anthropological place"(2000:57-58), a territory characterized by relational and historical identities, loaded with meaning by those who visit, and at the same time fully intelligible for the keen observer.

In this essay I work with some hypotheses to reflect upon the configuration of the toilet as space and its cultural resemantization; that is to say, the re-appropriation of the complex rituals, the symbolic processes, the imaginary references, the itineraries and confluences that mark the geography of a place and its daily routines. The study of graffiti in washrooms and the social exchanges that take place there is a pretext to analyze some of these micro markets of sexual communication and the nature of the gender/sexual relationships made explicit in the discourse generated by the men who frequent them. This paper was born out of my interest in documenting such cultural processes starting from the discursive mechanisms from which they originate.

The article draws on ethnographic fieldwork undertaken between September and December 2005 in Havana. Conducting this unusual fieldwork was far more difficult than I had anticipated because at the beginning, the people coming in and out of the washrooms while I was collecting the samplescamera and tape recorder in handwere scared of my presence and refused to be interviewed or answer any questions. I realized that participant observation for a regular period would facilitate to a certain point the interaction with some of these men. Participant observation requires the presence of the researcher in the place where the social practices unfold. In my case, those practices were completely different from the dynamics that take place in a peasant community, an urban plaza or a religious ceremony. I frequented three public washrooms in the central area of Vedadoone could say that I became a regulartrying to rid myself, as much as possible, of prejudice, in order to find answers to the hypothesis that I was constructing every day. I went in for a while, came out, talked to the doormen and to some of the "customers" in order to gather my graffiti samples and understand the dynamics and rituals of these places. Since I was aware of the ethical issues raised by similar studies1 1 For example, Humphreys was criticized for invasion of privacy, deception and misrepresentation of his identity. See Humphreys (1970). For criticisms of the ethical issues in Humphreys’ study, see also Punch (1986) and Berg (2001). , I disclosed my researcher identity to the men I approached at the washrooms entrance. Besides informal conversations, I also conducted five in-depth interviews with key informants. To ensure anonymity, all names have been changed.

Between Four Walls: space, discourse, and socialization in public washrooms.

Fitting perfectly Augé’s definition of an ‘anthropological place’, the public washroom offers its patrons a set of possibilities, rules and prohibitions whose content is both spatial and social. A place, notes Augé, "where individual itineraries intersect and mingle, where words are exchanged and solitudes are momentarily forgotten." (2000:72). Washrooms’ walls support a "delirious form of communication," (Silva Téllez, 1986) graffiti like, of sexual, ephemeral, and marginal natureparallel to the linguistic and ethical codes of the socially sanctioned channels of communication. These walls display an unadorned kind of literature. Its dialogic and performative messages addressed to regular or potential readers, might strike people of average sensibility who are prone to shame and disgust as something obscene and dirty.

The use of words that make direct reference to certain sexual, racial or social realities generates discomfort because they subvert or shatter the symbolic and historical frontiers of the public and the private; of what is expressed and what is unexpressable, which are part and parcel of the collective imagination. Thus the representations of so called "dirty words," "dirty" and "deviant" sexual practices and "foul gestures" are constructed in and exiled to a subcultural dimension of the low and the scatological. Such representations question not only the way of speaking of certain collectives but also their socio-cultural identity.2 2 See also on graffiti, Leap (1996), and on homosexual encounters in public places, Leap (1999).

Graffiti underscores an unusual pragmatics of communication; it is spontaneous, fleeting, furtive and anonymous. A foundational kind of writing, or according to Cuban author Margarita Mateo, "an exercise of criterion using a different assessment scale" (1995:22) where the reader is "fully certified to become the author (...) a fascinating exception in the universe of aesthetic discourses." (Garí, 1994:153).

The graffiti in the public washroom substitutes the voice, not the word, the moan or the grimace; it is the somatic mark of the lacerated and reconstructed body, the mark of the unheard, of the unpronounced. Filled by erectile and seminal pulsing, lines become signifiers of the audacious, of the transgressing: free and secret traces"metonymy of the phallus and the brush in hand" (Sarduy, 1982:76)undecipherable to a rational and forward reading; mise-en-scène staged by urban men eager to discharge their heart pulsations and fears, and their most intimate desires into that "secret" geometry. Graffiti acts as a territorial anchor; liturgy and masquerade to magnetize and attract. If, as Severo Sarduy asserts,

writing shapes and defines the subject, and stitches it together", the graffiti’s corollary is aimed at "laughing at authority, scribbling the norm, impeaching the inquisitors, smearing, staining, urinating and ejaculating on the immaculate, the perfect, the unreachable with its clarity and harmony (...) obscene announcement, knife to the canonical cloth, stone to the Mona Lisa, burning of the Temple of Ephesus" (1982:123).

William, a key informant in my research, explains:

People write on the walls of the washrooms as a way of voicing their unconfessed erotic desires; because of their repressed sexuality, this is how they can express or confess what they really want. In the washroom one cannot cuddle or talk. Interaction is impersonal. There are people who experience pleasure painting sexual scenes or writing insults or memories of an important sexual encounter, a story that marked their personal life. Others leave messages. One does not see poetry in these places, or literature or a dialogue out of chapter VIII of Lezama’s novel Paradiso (Interview with William in the home of my friend Ernesto on August 25, 2006).

The graffitiinherently discursiveis the principal mode of expression in the public washroom; it is the testimony, the primary source, the textual mark left behind by a subject who constructs and recreates the image of others and of himself. Graffiti explains the social processes and dynamics of these urban enclaves, allowing for the exploration of the communicative resources and interactional modes that reflect moods, wishes, anxieties, happiness, etc. It is not only a channel of verbal communication and a vehicle of cognitive and affective representations, but also a way to articulate relations. It permits the access of various forms of production and reproduction of interactional practices and sociocultural identity codes that configure the roles of the interacting subjects in the midst of sex-communicative processes, while functioning as a symbolic force that updates the power relations between the speakers and their respective social groups (Bourdieu, 1985:11).

In the interviews I conducted during my fieldwork, I realized that although these men share similar practices, their attitudes might be substantially different depending on a specific gender ideology, and are determined by logical interactions and various forms of socialization. Socialization involves the creation of social relations and the spaces where they take place. It is also associated with learning and internalizing social and behavioral norms and patterns (Ayús, 2005:62-63). The term socialization here refers to the creation and establishment of interacting contexts of greater or lesser complexity and stability. These contexts are, to a certain extent, systematic: the social life of an institution in this case the public washroomviewed as the social context that adds a peculiar nuance to the discursive practices that characterize it as such.

Public washrooms constitute interactional and discursive contexts that are subordinated to the socialization of their assiduous visitors and of their verbal and non-verbal practices, as well as to their daily performances which conform to a micro-local culture. As Ramfis Ayús holds, "socialization involves the creation and recreation not only of spaces but also of ways to conduct and exchange social meanings." (2005:33). Socialization in public washrooms is characterized by the existence of norms of verbal interaction that adopt peculiar features of the situated culture, that is to say, that possess their own specificity.

The writing/reading experience can create social bonds around a text; establish relations, and links among the subjects united around a particular message. Discourse is thus maintained in the midst of a literate and an illiterate socialization that is at the same time assiduous or potential, public and private. The writing also works as a pretext for encounters and can bestow sense and identity to a space and to those who call upon it repeatedly. An important element that should not be overlooked is the fact that the washroom is not only a geo-topographic or architectural demarcation, but also a point of deployment for a more complex sociability network and trajectories.

Homoerotic narratives and practices

One of my informants, Oscara middle aged barman who works at the Pío Pío cafeteriaexcelled as a naïve anthropologist in giving me the detailsas ethnocentric and biased as they were about the place and its visitors:

A bunch of homosexuals go inside to write on the walls and do weird things, the things their sort do...you know. They come every day, at any timein the morning, at noon, or late at night. They are both young and old. You name it. And it’s either homosexuals or women inverts and there are those who come just to look, and those who come to bang homosexuals. That washroom is a depravity. A guy gets in first, and then another follows and they stay for an hour and then another one gets in, and another, and so on. It’s a small washroom but it can take eight or ten guys. There have been fights because they start looking at a guy who’s just urinating. But in general, they keep it quiet. They enter and stay in for a while and then the one who’s done leaves. That’s how it works. The one who’s already been banged waits for his pal to get banged too and so on and so forth (Interview with Oscar, barman at the Pio Pio cafeteria, Wednesday September 28, 2005. Emphasis is added.)

The details of the barman’s testimony reveal how otherness is marked by the eye that observes the object being observed. Firstly, when he says that the men who frequent the washroom "do weird things, the things their sort do...you know," there is an implicit lack of knowledge of these kind of sexual practices: even when they are presupposed, they are not explicitly enunciated, precisely to underscore the distance between the group he is referring to and the one to which he belongs. I find in the barman’s ideas two dichotomous and opposing orders that are inscribed in two dimensions: his own normalcy and the abnormality to which he is placing the "washroom visitors," marked by the idea of rarity and alienation.

On the other hand, his testimony discloses the categories attributed to the men he has been describing and to the performance and distribution of sexual roles supported by a culturally construed masculine/feminine dichotomy, with two opposite poles as referents: activity vs. passivity, that is to say, those who penetratethat according to my informant are "those who bang homosexuals" and those who are penetrated, i.e., "the bunch of homosexuals [who] go inside [the washroom] to get banged."

For anthropologist Guillermo Núñez Noriega, this is one of the main characteristics of the dominant model of understanding homoeroticisms. Furthermore, he states that this classification of individuals according to their roles is a "metonimization" based on their sexual organs. That is, the homoerotic subject is reduced to an "anal receptor," the homoerotic body is understood as an "orifice" and homoerotic desire is understood as the "anal desire of a penis." (2001:22-23).

Paco, another informant, is a jovial old man who works as a night watchman at the public washroom situated in the park honoring the sad and fictional knight, Don Quixote de la Mancha in 23rd and J Streets. The tiled walls of this washroom prevent graffitists from expressing themselves. Consequently I couldn’t collect any samples. However, whenever I went there, I did notice the intense sexual activity going on, inside and outside. To this Paco commented:

Our clients are homosexuals, and people who don’t work, thieves, pickpockets, you name it. It’s a public washroom in Vedado. Most of the homosexuals come alone, but others come with their partners. They can’t arrive hugging or holding hands coz I won’t allow it. This isn’t a motel. Sometimes when they come in couples, one of them waits outside while the other one goes in. It’s inevitable, one cannot control it. But when it gets packed inside, I go in and kick them out. They can go to a park to talk or to touch themselves or whatever. What we have here is a lot of peeping which is normal. We have the respectful homosexual and the disrespectful onehe laughs nervously, who gets carried away and starts touching the one standing next to him. He laughs again (Interview with Paco in the public washroom of El Quijote Park, on Wednesday, September 28, 2005).

In this testimony, homosexuals are cast in the same criminal dimension as "vagrants, thieves and pickpockets." However, the latter could be using homoerotic bait as a masquerade to perpetrate a criminal activity against vulnerable men who are avid for sex. Moreover, the old man’s representation of homosexuality is based on "respect," understood as the abstinence from "peeping" and "touching."

However, despite the doubts expressed by the sentinels of some city public washrooms, there are stalls known as "reserved compartments," where visitors can enjoy more privacy after paying money to the night watchmen.

During my fieldwork, I noticed that outside the washrooms one could always find a pair of peeping toms gazing eyes waiting for the opportune moment to get in. Yunior, a recurrent face in some washrooms, furnished me with lots of clues. Here’s his description of some of these individuals:

That’s the typical bugarrón (macho banger) who only seeks his sexual satisfaction, without caring for the other’s. He’s moved by his instincts, and doesn’t get involved sentimentally. You’ve seen them, they look like vultures waiting for men like me, visibly effeminate gays in need...They play the macho role and conceive homosexual sex as an act of penetration: no kisses, no caresses, nor the slightest show of affection. You can’t even look at them intently because they get self-conscious. For them it’s just ‘turn around and get on with it.’ All’s quick. Once they ejaculate they walk out on you. They don’t care if you are done or not. That’s not their problem. If they like it, they’ll tell you the hours and days when they come, so that you can wait for them; if not, they write on the wall their information for all to know. But it can also be, I’m not sure, that since they don’t have anyone to talk to, they write on the walls out of a need to express what they feel. These places are well known and they come to let go. When I’m not dating anyone, I like to come here and I always find relief. Here or somewhere else: the shells of ruined buildings or in the bushes because I don’t have money to pay for a room and even if I had, none of them would go with me anywhere because you can tell they are family men.3 3 Humphreys’ classical study pointed to public spaces such as ‘tearooms’ in which straight-identified men have sex with men (see Humphreys, 1970). However, while he was interested in ‘deviant’ behaviour, I want to call attention to washrooms as interactional and discursive spaces of a larger urban homoerotic network or ambiente. And also no one’s going to rent a room to two fags unless one is a foreigner with dollars to spend.

This testimony contains some useful elements with which to analyze the discourse and practices of public toilets' regulars. Metonymic and metaphoric recourses explain ongoing dynamics and their positioning. When using analogies, i.e., when referring to others as vulturesmy informant describes an interactional and cultural situation. This narrative recourse is a valuable socio-anthropological tool to decipher the relations that take place between the actors and at the same time, to discover the modes in which these practices are narrated, how they are organized at an individual and collective level and how they are expressed. Rigo, a young lathe operator, uses a similar narrative in his description of interactional dynamics: "In these washrooms a guy can be swarmed and licked all over as flies do to a sweet. There is no talking; the most you hear is ‘move away’! That’s why I don’t like washrooms; they make me feel out of place, I can’t stand the promiscuity or the stench." However, other testimonies, more in tune with the scatological conception of sex, contradict Rigo’s. "The stench turns me on," confesses Ernesto, "that mix of men’s urine makes me hard. I can’t avoid it; it enhances my fantasies."

Some offers and demands expressed in the graffiti point to men who respond to traditional canons of masculinity and who don’t think of themselves as homosexuals, notwithstanding their involvement in sexual encounters with same-sex individuals. The following graffiti, in addition to indicating what the peak hours in the year 2004 were, illustrate some of the rituals taking place during these encounters as well as the reproduction of stereotypes and homoerotic schemes of representation. A certain functionality is recurrent in the style of publicity. They are all structured following the offer and demand pattern, especially in their superlative promises and assertions of "the quality of the product" up for offer.

1. I fuck men in the ass. If you live alone and want to meet me, come Friday April 23 at 2. p.m., I’ll be wearing white.

2. Mulatto man, big dick, loves asses, and getting sucked. Tell me how we can meet.

3. Place: here. Time: Tuesdays or Wednesdays from 4.30 to 5 p.m.

4. I bang sissies. Tuesdays 6-4-04.

5. Big, fat dick. I like lightly built, hairless, passive guys. Every day from 4.30-7 p.m.

6. I come here every day. I have an 8-inch, fat dick. I’ll be waiting.

7. I have a big, fat dick. I come here daily from 4:30- 6:30 p.m... Give me a sign. 4 4 These graffiti were collected at the Pio Pio washroom situated in L street between 15 th and 17 th streets, on Wednesday September 28, 2005. I have respected the linguistic register: 1) Singo a hombres por el culo. Si quieres conocerme y vives sólo ven a verme el viernes 23 de abril a las 2: PM, vendré vestido de blanco. 2) Soy mulato y de pinga grande y me gustan los culos y que me la mamen, dime cómo vernos. Lugar, aquí, Hora, martes o miércoles de 4:30 a 5 PM. 3) Parto a maricas. Martes 6-4-04. 4) Tengo una pinga grande y gorda y me gustan los pasivos y lampiños y que no sean fuertes. 4:30-7PM, todos los días. 5) Todos los días vengo. Tengo una pinga de 8 pulgadas y gorda. Te espero.6) Tengo una pinga grande y gorda. Vengo todos los días de 4:30 a 6:30 PM. Dame señas.

In these discourses, the penisparticularly one of extraordinary size and bulkis inscribed as symbolic capital in the economy of pleasure and stereotypes to seduce anal receptors. These "penile codes"5 5 I borrowed the concept "penile codes" from Peter Beattie’s "Códigos ‘peniles’ antagónicos. La masculinidad moderna y la sodomía en la milicia brasileña, 1860-1916" (1998:109-139). are aimed at establishing sexual roles that are ascribed to masculinity. Race is also part of the symbolic capital for negotiating these kinds of exchanges, appealing to cultural myths related to historical sexual symbols. The contradictions manifested in these discourses are born out of the self assessments and denominations used by heterosexuals and homosexuals. These denominations create meanings and constitute ways of assessing and depreciating objective and subjective conflicts of individuals. They represent attributive categories; generally submit to the performance and distribution of sexual roles that are supported by the masculine/feminine representation dichotomy; and are constructed taking as a referent two opposite poles: active and passive, i.e., the one who penetrates and the one who is penetrated.

For that reason, many individuals who have an obvious homosexual life style have developed a self-acceptance resistant strategy to fight against that categorization. In Cuba, males who have sex with other males without considering such practice homosexual are popularly known as bugarrones. This term works as a euphemistic strategy that puts them in a position which allows them to get in and out at will without garnering a pejorative connotation.

Gender role performance is part and parcel of homosexual sociability. Indeed, there are some who still continue to reproduce traditional macho roles for the advantages and prestige they garner. Even though these men are fully aware of their feelings and sexual desires toward other men and perceive that as a psychological difference, they neither define nor accept themselves as homosexuals in spite of the fact that homosexual intercourse is for them a customary practice. For some, this feeling of difference, their context and their circumstances will inevitably make them accept their homosexuality. But this is a long process which might take years. Others, however, show great resistance to accepting their homosexuality and subscribe to categories such as bisexual or no category at all.

What Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick coined as "the epistemology of the closet" is a useful means of understanding how sexual diversity is negotiated and how individuals acquire a differentiated, socio-sexual conscience that will eventually crystallize or not in a homosexual identity. Due to the "closet’s" sediment and structure, it is not easy for an individual to step out of it entirely.

The closet is not inscribed simply on the subject as an internal/external time/space, but it exists, on two dimensions at once. As Didier Eribon notes, "One is never totally inside the closet because (...) it is a secret that always gives itself away and there is always at least one person who seems to know, or whom you suspect must know. And so you can never be fully out [the closet] because from time to time it is necessary to silence what one is." (2001:160).

The study of these washrooms suggests that indeed, homosexuals feel comfortable and enjoy their freedom in them; however, they assume a discrete demeanor in family and other social spaces. This is true also among overt homosexuals who at some point in their lives have had to go back to the closet (Kosofsky Sedgwick, 1990:68-70).

Nowadays, it is increasingly evident that there are various configurations and countless practices of masculinity. There are various ways of being a man and assuming a masculine role. Evidence proves a certain estrangement from the traditional macho model. However, there is a certain stagnation of masculine representations at a macro social level, which vary depending on space and context. Similarly, with regard to the "closet", the notion of masculinity in contemporary society continues to be a straightjacket for many people who have to live in the borders of anonymity and clandestinity to be able to carry on with their lives as full human beings. Williamone of my intervieweesshared with me his inner conflicts regarding masculinity and the way he displays his sexuality:

I live in Los Pocitos, amongst the macho Abakúa religious men, and there, people examine you night and day. Your manhood is constantly tested; cohabitation codes are very strict, tough, even violent; stereotypes are taken to extremes and women and sissies are nothing. Imagining men from my neighborhood with their deep seated stereotypes, sucking dick or being penetrated, really turned me on and helped me to cushion my unconscious and inevitable feelings of guilt. It helped me realize that I am not a monster or a circus freak, or a pervert; but above all, that I am not alone.

Public washrooms are places charged with meaning and function as referent for a group of males who carry out sexual and discursive homoerotic practices. However, many homosexuals reject these spaces or feel uncomfortable in them, out of prudishness or prejudice.

The testimony of Ángel Luis illustrates the complexities of these interactional processes:

The washroom in Quixote Park is for promiscuous and flamboyant pansies. I don’t like to be seen there because it’s like a bright spotlight on you, loudly screaming: ‘I’m a fag!’ I could literally be peeing in my pants but you won’t catch me going in there. I ignore it. Imagine if a friend saw me going in. It would be extremely embarrassing (Interview with Angel Luis July 17, 2006 in Malecón [sea front wall]).

It seems that, for him the washroom is as a sort of coming out act whose cost he is unwilling to pay. Even though Ángel Luis does not go to public washrooms looking for sex, he did confess frequenting other sites. The fear of being discovered is revealed by a negative representation of "those promiscuous and flamboyant pansies." It is significant that he used the adjective: "spotlight,"meaning clarity and identity disclosureto describe the place.

The testimonies cited reveal micro-sexual markets with a wide variety of offers and demands that do not necessarily involve money but rather social prejudice, fear of disclosure, and censorship and self-censorship. These behaviors lead to dual ways of living that are uncertain and ambiguous, clandestine and itinerant, anonymous, and unprotected and thus dangerous, and in order to document them, we only have the literature of the love graffitia kind of love that still in the 21st century, "does not dare to say its name."

The washroom does not operate within the economy of commercial abstraction or sex-service where there is a contractual relation mediated by money and the value of each objectin this case subjectdepends on its "use value" , that is to say, on a merchandise that does not have a work product. The prevailing economy in these places is part of a symbolic exchange, in which the objects’ meaning and worth is established by the men who exchange them and the object is a space of encounter and constitution of the subjects: an inscription, then, in a different logic of ambivalence and desire (Barbero, 1981).

The graffitis transcribed above have their counterpart in messages inscribed in this economy of pleasures as "passive":

1. I’m a faggot who likes having his ass sucked and sucking dicks. I like light-skinned mulatto men and blacks. I come every day. How can I see you?

2. The happiness of one man is holding the dick of another man.

3. I’m a brunette and I am looking for a black man with a big dick. I come every day from 5 PM to 7 PM.

4. I want a big dick. 4: 30 to 7 PM, every day.

5. I’m half Chinese. I come every day and I suck madly.

6. My name is Roberto. I enjoy men. I’ll wait for you on Wednesday March 17-04 at 4:30 PM.

7. I’m looking for someone with a big dick like this one (arrow pointing toward a sketched penis). I’m crazy for someone to make me feel full to the rim of a man.

8. I need a big macho man. Write your name and phone number here so I can find you.6 6 1) Soy maricón y me gusta que me mamen el culo y mamo pingas. Me gustan los mulaticos y los negros. Vengo todos los días, ¿cómo puedo verte? 2) La felicidad de un hombre es la pinga de otro hombre. 3) Soy trigueño y busco un negro que tenga una buena pinga. Vengo todos los días de 5 PM a 7 PM. 4) Quiero un buen pingón. 4: 30 a 7 PM todos los días. 5) Soy medio chino, vengo casi todos los días y me gusta mamar como un loco. 6) Me llamo Roberto. Me gustan los hombres para gozarlos. Te espero miércoles 17-3- 04. 4:30 PM. 7) Estoy buscando a alguien con una morronga así (señala una flecha con un gran pene dibujado), estoy loco porque alguien me haga sentir de verdad lleno de hombre. 8) Necesito un machón. Pon nombre y teléfono para localizarte.

Others like Rafael say: "I’m looking for someone serious to have sex with, not a partner. I do everything and like having fun. I come every day from 4.30-7 p.m. Give me a sign." A new categorycompletosrefers to those gay men who practice a wider range of sexual possibilities, positioning themselves outside the traditional relational canon of active/passive.7 7 Similar categories have been described in other Latin American contexts. See for instance, Núñez Noriega (2000) and Fry (1982). They consider that these roles restrict not only sexual experiences, but also partnerships and homosexual group relations.

The same goes for another anonymous writer: I love doing and being done: That’s life, madness, sex." The verb [to do] is used figuratively. The image can be understood as a code of phallic penetration in which the speaker underscores his disassociation from the traditional economy of sexual roles, and his willingness to get involved in a more open exchange. These types of messages are, indeed, a rarity in my graffiti compilation. However, the verb used speaks eloquently to an intrinsic symbolic violence in the sexual conception and representation of these "penile" codes.

Perhaps, interest in preserving anonymity is one of the reasons for the fleeting and furtive characteristics of this kind of textual production. But for many the washroom has become a way of life: the regular handwriting and style of the same writer indicates that this so. William describes it like this:

There are people who have incorporated these spaces as part of their daily routine, and adopted them as their own homes. Others take it as a place to get initiated, to satisfy sexual desires or to experiment.

Some seem to find full satisfaction and abandon themselves temporarily to the promiscuity of these relations and address codified messages regularly to another particular writer: "I need to see you, it’s urgent. Coming? I’ll be waiting on 4-8-04 at 3.30 PM." Many messages reveal the slow hours and/or days of a particular washroom. A disappointed writer scribbled: "The washroom is in a slump today: nobody showed up from 12 to 3.10 p.m."

Economic scarcity, housing problems and the absence of private spaces (like motels or rental housing) for homoerotic encounters along with other psychological factorsinsecurity about establishing relations outside the four walls of a room, prejudices that torpedo self-acceptance and advocate strongly for traditional homoerotic representationsseem to influence decisively on the burgeoning of this type of sexual practices. Several interviewees think that many of these factors support promiscuity. Others, despite acknowledging the considerable impact of these obstacles on the existence of these types of interactions even with the suppression of these barriersconsider that these hidden places will continue to exist for people who enjoy casual homosexual sex. In this regard, Jesús added:

Many of the people who come here do not want to be involved in a sentimental relationship or have a life partner. That’s not their priority. They come here to satisfy a homosexual need and then go on with their lives. Promiscuity is addictive; there are fears and risks involved in a commitment. So, it’s more comfortable to satisfy your sexual needs this way.

Alain, a squalid adolescent who after several attempts to intercept him coming out of a washroom, finally consented to be interviewed:

It is common to find more sexual flexibility in homosexual couples who have been in long-term relationships. This might sound bizarre because there is this false idea that homosexuals are possessive and hyper jealous. While this might be true at the beginning of the relationship; with the passage of time, it’s normal that they want to have sex on their own, maintaining the sentimental bonds but relaxing exclusivity to have sex with other people. Cohabitation is preserved out of friendship and because it’s difficult to find a place of one’s own; so they continue sharing the same space but each one for his own as far as sex is concerned. They can even introduce a sex trick to each other (Interview with Alain Jun16, 2006 in the park in front of The Quixote washroom).

The politics of graffiti

One of the most important elements in the graffiti sample I collected concerns public identity based on sexuality and homosexual rights. This graffiti possesses a participant and interactive dialogic dimension, at least on a primary level which involves writers of various sexual orientations. Although dialogue and political debate are restricted to four walls, some members of this writers’ community and assiduous or potential readers represent an alternative cultural practice, impossible to control, that somehow subverts the traditional power structures that have condemned these groups to ostracism, illegality, and a subculture, thus making impossible any public form of debate on this issue.

Messages like this one prompted the attention of some "writers" who made comments and invited others to join in the debate and dialogue: "Long live the Cuban Gay Community," euphorically proclaimed one in large blue print in the Pio Pio washroom. Below, another dissident, skeptical writer retorted: "Which Community?" This dialogue is very interesting and deserves comment. Ever since I began studying these places, I realized that they played an important role in establishing networks of marginal sexual exchange as a part of what I have called a homoerotic ambiente (milieu, environment). This is a spatiotemporal dimension that brings together not only homosexuals but individuals of various sexual orientation or identities and serves to share cultural processes, linguistic, and aesthetic codes, as well as to set up a network of friends. This is chiefly a night environmentinformal, unstable, and itinerantconstantly being reconfigured and moving across the map of the city. The idea of ambienteas opposed to the term community, that many try to defendoffers a more accurate idea of the negotiations that take place there between these groups and government institutions in order to create spaces of socialization, even if they lack a collective consciousness. The notion of ambiente is a more satisfactory term to refer to the subcultural and peripheral mode where these exchanges unfold and it is taken from the shared linguistic codes of these groups (Sierra Madero, 2006).

Another writer got into the debate to rebuff the content of the texts and to demand: "Stop writing nonsense. It’s your fault that everyone turns against us. Thank you." Maybe he thought that the coarse language of graffiti reinforced the underrated and distorted image that society has of homosexuals (-something I am not particularly sure of). This graffiti is intended as persuasion: its writer uses a pragmatic argument: cautioning and arousing fear about the undesirable consequences that such messages might have. Even though the speaker is part of these practices and exchanges, he doesn’t share in the contextual discourse. His statement is a rupture, an estrangement from the group he is referring to: "It’s your fault." Clearly, the speaker is reaffirming his position vis-à-vis the contextual dynamics and the scriptural logic of the others, which he disapprovingly represents and blames for"everyone turning against us"that is discrimination, and social normative sanctions at the same time uncovering his own ideology.

In the washroom of the Central Library of the University of Havana, I collected a large sample of a graffiti debate that opened with a call for tolerance toward homosexuals: "This is for non homosexuals. Take a look at homosexuality; but at its good side. Believe that they can be your friend and have the best of relations with you, based on respect." Even though the speakers’ intention and plea are valid, I do not see how homosexuality can be categorically defined as good or bad. This messagefilled with grammatical errors although written in an university milieuemphasizes the abjection and the abnormality of homosexuality versus heterosexuality, signaling a widening cultural gap.

This writer was summoned and rejected by two others. One of them was very succinct: "Yes, you imbecile." The second one retorted in the same vein: "Or you faggot. Respect, perhaps; understand, never." It is paradoxical how these rejections and homophobic statements did not appear in the washrooms situated in "non literate" areas, that a more heterogeneous group frequents but at the University of Havana where one might expect a more sophisticated forum of debate. The last two messages have replies by two other contestarian writers: "Narrow-minded people like you have caused the world the greatest harm. Watch out for your intransigence, it could be hiding your homosexuality." The debate continued in the texts of yet two more writers. One of them noted indignantly: "Bunch of faggots!" and another: "I fight for normalcy. Deviants have no rights."

The Last Try

The washroom is more than a geo-topographic or architectural demarcation; it is a complex location where sociability networks and trajectories meet. These urban trajectories crisscross other places and meeting sites which are more clandestine and have other interactional dynamics. Those are open air places, propitious for more clandestine sexual exchanges than the public washrooms but in which similar dynamics take place. There are enclaves situated in the municipality of Plaza de la Revolución, in the vicinity of some hospitals and around G and Zapata Streets. These places have been unified through metaphors and analogies and now they are known as ""The Last Try." "The Last Try" refers to the end of sexual itineraries and trajectories. Ángel Luis describes it:

It’s like a reminder for whoever goes out at night in need of sex or hasn’t been able to do a trick that they can always stop by those places and will surely get some action. Some people just come out of a party and stop there before going home; others are regulars, and some others go for a while and then disappear for a time. It depends. I began frequenting these places in 2003, 2004. Then I was in a relationship and never went back until recently when I broke up with my partner and decided to update my sexual agenda (Interview with Angel Luis, ibid.).

All the interviewees who frequented not only "The Last Try," but other spaces, namely the fountain near the Hospital of 26th Avenue, the areas adjoining the dark leafy arbors of the Sports Coliseum (on Racho Boyeros Avenue), the Quinta de los Molinos (on Salvador Allende Avenue from Infanta to Zapata Streets), the park of the Escuela Normal (Infanta and Amenidad Streets), or the hidden rugged beach the Playa del Chivo (beneath the El Castillo del Morro) among other sites, agree that although these places are good for sexual catharsis, socialization is less impersonal than in public washrooms. William explains:

It’s very unlikely to find affection there, because those places are meant for casual sex and no sooner do you exit its geographic limits, then nobody will know you, say hi, or look you in the eye. The sexual event is left behind. However, you might find friends there to share experiences, talk well into the early hours of the morning. I’ve made some friends there, wonderful people of various social strata and professions. I have been made love to with a Biblical text: ‘He that is faithful in that which is least is faithful also in much’ and I’ve fallen for it, but real life is different. Some even want to exchange phone numbers and prolong the encounters for a while, but many avoid getting into a personal relationship (Interview with William, Ibid.).

Enrique’s testimony offers other nuances about the dynamics and interactional logic of these places:

All the men who go there are looking for one thing: sex; those who don’t, walk pass the place without even looking at it. But those who stop are into it and you can do them. Wake up dude! If we are there it’s because we’re in it. Some pretend to be peeing, but they’re actually just displaying their genitals as goods in a shop window. Most of the time there is no talking, no affective touching. You can be sucking a guy’s dick, and he’ll turn his face away. No word is exchanged and if anything is said it’s always very impersonal, anonymous. Even the names are false. I always use the name Alejandro when I go to these places. Mutual pleasure is not involved. It’s a race to ejaculate, because the one who’s done first walks out on the other without saying a word. Sometimes, it’s happened to me, I’m told: ‘suck it but don’t touch me. Don’t get close, get off me (Interview with Enrique May, 10, 2006. Nearby to "The last try").

Some of my informants agreed that traditional sexual roles are toned down in these places. Héctor admits that

those who insist on difference are beginners. For veterans, everything goes; it all depends on the person with whom they are interacting. Most of the people in these places tend to be reciprocal in sex: they do everything, although some only consent to mutual masturbation.

However, according to the testimonies there is a regular attendance of bugarrones. Those are described as

real men, who lead heterosexual lives, but who go there to use homosexuals as outlets to satisfy their sexual appetites. Many arrive drunk to justify same-sex sex. Beatings after sex are not uncommon because most of these guys still have a repressed sexuality and tend to channel their guilt through violence (Interview with Héctor May, 7, 2006. In Ernesto’s house).

It would appear that these places are frequented by some men who pretend to want sex to attack and rob homosexuals. My informants point to the absence of solidarity that prevails in these places. William comments: "If a guy gets knifed nobody intervenes and everybody runs out naked or with their pants down. The attackers lure their victims into having sex to rob them. Once it’s over, they steal all that’s worth anything and get the hell out." Ernesto shared his experience:

I wouldn’t be caught dead going to those bushes. One night I was really horny and asked a friend of mine to get me somewhere to mitigate my itch. He took me to a place next to the Calixto García Hospital and I remember that while we were trying to do this gorgeous boy, I saw, in the distance, these two guys who you could tell were out of the game and I left quickly. I realized that you should go to those places wearing shorts, as if you were going to the beach. I honestly saw myself stabbed in the back. Those dudes didn’t look like bugarrones to me but like killers (Interview with Ernesto Jun, 26, 2006. In his house).

According to some testimonies, negative feelings abound in these places including, as the most typical form of socialization, lack of solidarity and jealousy. William explains: "some fags are terrible; they feel jealous when they see you talking to a hot guy and they try to scare him off by claiming the police or attackers are coming."

Some of my interviewees explained that the number of people willing to participate as audience for male same-sex sex in those places is significant. Equally common, they observe, are homosexual couples looking for a third party to have sex. During my fieldwork I discovered that mostly during the weekends cars stopped, honked their horns or flashed their lights looking for young people to form trios.

The linguistic codes and registers used in these places are as rich and varied as the social and cultural backgrounds of the interacting individuals. Among the most common and popular phrasing are: "matar jugada" (to kill the play), "descargar" (to use as outlet), "matizar" (tone down) or simply as William puts it: "A doctor told me once: ‘I’m just off my night duty, Care for something?’" These codes are often times accompanied by interjections and non-verbal or paralinguistic elements such as whistling or signing to call the other’s attention.

Conclusions

Some twenty years ago, socio/sex/affective relations began to change. AIDS modified the relational modes that humans had designed up to this point. This pandemic began to inflict death, insecurity, prejudices and myths on human life. Ever since the first AIDS case was detected, a variety of mediatic campaignsdirected at first toward the homosexual community and prostituteshave been implemented. However their content has not substantially differed. Ongoing public policies and campaigns today continue to be extremely conservative, prudish and heterosexist and ignore the socio-sexual projection of other groups, thus hindering the implementation of actions to protect and inform them. These sectors have a more complex sexual existence with a certain tendency toward repressed or unconscious bisexuality.

AIDS studies in Cuba indicate a high incidence of the disease among what specialists have named MSM (men who have sex with other men). Statistics show that they represent 65% of those diagnosed and 83,4% of the men infected (Chacón Acosta, 2002:13). Of the washrooms I visited during this unorthodox field work, none displayed any evidence that their visitors engaged in protected sex using condoms nor did I find any graffiti referring to the impact of AIDS or other sexually transmitted diseases. Neither did I come across any kind of tabloid or education or prevention propaganda, which indicated that these are the most vulnerable places to get infected by communicable diseases. In a conversation with a young doctor who collaborates with the Centro Nacional de Prevención de ITS y VIH (Sida) (National Center for the Prevention of STDs and HIV-AIDS) I confronted him with inconsistencies in the Center’s prevention strategies and one of the excuses he used was the high cost of condom dispensers; adding that: "Those dispensers are very costly and you know how it is, you put them in a public washroom, say the one in Quixote Park and before the week’s over it will be kicked down or whatever." I could not suppress a hint of irony and sarcasm when I asked him: "Isn’t the human, symbolic or economic cost in terms of medical care and purchase of retroviral medicaments significantly higher than getting condom dispensers?"

Paradoxically, many of the people I interviewed told me that sex in places like "The Last Try" is safer although the scenario is more dangerous. William comments: "Most of the people bring condoms and among those who don’t, it’s because they will engage in masturbation. People in these places are well aware of HIV and STD prevention. Besides many of the regulars are nurses, doctors or health personnel, so preventionhe says with a sardonic smileis guaranteed."

Another aspect that stirred my curiosity in the washrooms I visited was the absence of heterosexual feminine narratives. In the "ladies" washrooms I found not even an analogous trace of the kind of narratives I found in men’s or unisex washrooms. It would be difficult to catalogue graffiti written by women. It seems that washroom writing is an exclusive need and practice of male homoeroticism.

These group networks must reconfigure their practices depending on the context and the new socio-cultural conditions imposed on them in order to survive. The shift and usurpation of other city spaces was one of the mutations endured by the group network that frequented the Pio Pio washroom as they were forced to migrate to and experiment in another space when that washroom was shut down, thus burying both its graffiti and its practices behind a concrete wall.

Raul Castro’s government has opened new opportunities for small private businesses such as house renting. New research is needed to know whether landlords’ prejudices against renting homosexual couples are changing and whether these new opportunities are significantly altering the interactions here described. Yet, just walking around the Last Try is enough to confirm that these interactions remain. Unlike their Latin American counterparts, Cubans cannot freely access the Internet, and so dating websites and chat rooms have not substituted washrooms and urban sites as homoerotic pick-up places. In any case, given that these men are compelled by the excitement of border and dangerous practices, online interaction might not offer the same experience.

Bibliography

AYÚS REYES, Ramfis. 2005. El habla en situación: conversaciones y pasiones. La vida social en un mercado. México. D.F.: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes.

BARBERO, J. Martín. 1981. "Prácticas de comunicación en la cultura popular." In: SIMPSON GRIMBERG, M. Comunicación alternativa y cambio social. pp. 237-251. México DF: Ed. UNAM.

BEATTIE, Peter. 1998. "Antagonistic Penile Codes. Modern Masculinity and Sodomy in Brazilian Militia from 1860-1916". In: BALDERSTON, Daniel & GUY, Donna J. (comp.) Sexo y sexualidades en América Latina. Buenos Aires: Editorial Paidós.

BERG, Bruce. L. 2001.Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (4th ed.). Boston and London: Allyn and Bacon.

BOURDIEU, Pierre. 1985. ¿Qué significa hablar? Economía de los intercambios lingüísticos. Madrid: Editorial Akal.

CHACÓN ACOSTA, Leonardo L. 2002. "La prevención del VIH. Entre los hombres que tienen sexo con otros hombres (HSH)". Revista Sexología y Sociedad, año 8, no.20 Dec, 2002.

ERIBON Didier. 2001. Reflexiones sobre la cuestión gay Barcelona: Anagrama.

FRY, Peter. 1982. "Da hierarquia a igualdade: a construção histórica da homossexualidade no Brasil" In: EULÁLIO, A (comp.) Caminhos cruzados: Linguagem, antropología e ciências naturais. pp.87-115. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar.

GARI, Joan. 1994 Análisis del discurso mural. Hacia una semiótica del graffiti. Tesis doctoral, Departamento de Teoría de los Lenguajes, Universidad de Valencia.

HUMPHREYS, Laud. 1970. Tearoom Trade. Chicago: Aldine.

KOSOFSKY SEDGWICK, Eve. 1990. Epistemology of the Closet, Berkeley & Los Ángeles: University of California Press.

LEAP, William. 1996. Word’s Out: Gay Men’s English. Minneapolis: Univ. Minn. Press.

LEAP, William (ed.). 1999. Public Sex, Gay Space. New York: Columbia Univ. Press.

MATEO PALMER, Margarita. 1995. Ella escribía poscrítica. La Habana: Casa Editora Abril.

NÚÑEZ NORIEGA, Guillermo. 2000. Sexo entre varones. Poder y resistencia en el campo sexual. México D.F.: Porrúa.

NÚÑEZ NORIEGA, Guillermo. 2001. "Reconociendo los placeres, desconstruyendo las identidades. Antropología, patriarcado y homoerotismos en México". In: Desacatos. Revista de antropología social., No 6, primavera-verano 2001, pp. 22-23. CIESAS, México, DF.

PUNCH, Maurice. 1986. The politics and ethics of fieldwork. London: Sage.

SARDUY, Severo. 1982. La simulación. Caracas: Monte Ávila Editores.

SIERRA MADERO, Abel. 2006. Del otro lado del espejo. La sexualidad en la construcción de la nación cubana. La Habana: Casa de las Américas.

SILVA TÉLLEZ, Armando. 1986. Una ciudad imaginada. Graffiti, expresión urbana. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Submitted: 10.11.2012

Accepted: 11.19.2012

- AUGÉ, Mark. 2000. Los "no lugares", espacios del anonimato. Una antropología de la sobremodernidad Barcelona: Gedisa.

- AYÚS REYES, Ramfis. 2005. El habla en situación: conversaciones y pasiones. La vida social en un mercado México. D.F.: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes.

- BERG, Bruce. L. 2001.Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (4th ed.). Boston and London: Allyn and Bacon.

- BOURDIEU, Pierre. 1985. ¿Qué significa hablar? Economía de los intercambios lingüísticos. Madrid: Editorial Akal.

- ERIBON Didier. 2001. Reflexiones sobre la cuestión gay Barcelona: Anagrama.

- GARI, Joan. 1994 Análisis del discurso mural. Hacia una semiótica del graffiti. Tesis doctoral, Departamento de Teoría de los Lenguajes, Universidad de Valencia.

- HUMPHREYS, Laud. 1970. Tearoom Trade Chicago: Aldine.

- KOSOFSKY SEDGWICK, Eve. 1990. Epistemology of the Closet, Berkeley & Los Ángeles: University of California Press.

- LEAP, William (ed.). 1999. Public Sex, Gay Space New York: Columbia Univ. Press.

- MATEO PALMER, Margarita. 1995. Ella escribía poscrítica La Habana: Casa Editora Abril.

- NÚÑEZ NORIEGA, Guillermo. 2000. Sexo entre varones. Poder y resistencia en el campo sexual. México D.F.: Porrúa.

- PUNCH, Maurice. 1986. The politics and ethics of fieldwork London: Sage.

- SARDUY, Severo. 1982. La simulación Caracas: Monte Ávila Editores.

- SIERRA MADERO, Abel. 2006. Del otro lado del espejo. La sexualidad en la construcción de la nación cubana. La Habana: Casa de las Américas.

- SILVA TÉLLEZ, Armando. 1986. Una ciudad imaginada. Graffiti, expresión urbana Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

20 Dec 2012 -

Date of issue

Dec 2012

History

-

Received

10 Nov 2012 -

Accepted

19 Nov 2012