ABSTRACT

Cardiac arrhythmias are common in horses and can lead to a decline in performance and sudden death. The use of cardiac pacemakers in horses has been poorly investigated, with a scarcity of description and development of techniques for the device implantation procedure. This study therefore aimed to develop a new technique for epicardial pacemaker implantation in horses using video surgery. Five equine cadavers were used as models for the application of the video surgery technique applied for the implantation of an epicardial pacemaker via transdiaphragmatic and intercostal access. This technique was effective at fixing the pacemaker electrode to the left cardiac apex of five cadavers used as a study model. The surgical procedure was minimally invasive, with an average surgical time of 44 min. No lesions were observed during a horse necropsy performed at the end of the surgery. Pacemaker implantation via thoracoscopy and intercostal access is innovative and represents a potential therapeutic novelty in the treatment of horses with severe cardiac arrhythmias.

Keywords:

arrhythmia; cardiac; heart; left ventricle; video surgery

RESUMO

Arritmias cardíacas são comuns em cavalos e podem levar a uma queda no desempenho e à morte súbita. O uso de marcapasso cardíaco em cavalos é pouco estudado, e há uma escassez de descrição e de desenvolvimento de técnicas para o procedimento de implante do aparelho. Portanto, este estudo teve como objetivo desenvolver uma nova técnica para a implantação de marcapasso epicárdico em cavalos usando-se videocirurgia. Cinco cadáveres de equinos foram utilizados como modelo para a aplicação da técnica de videocirurgia aplicada para a implantação de um marcapasso epicárdico via acesso transdiafragmático e intercostal. Essa técnica foi eficaz na fixação do eletrodo do marcapasso no ápice cardíaco esquerdo dos cinco cadáveres usados como modelo de estudo. O procedimento cirúrgico foi minimamente invasivo, com tempo médio de cirurgia de 44 minutos. Não foram observadas lesões durante a necropsia dos cavalos realizada ao final da cirurgia. A implantação de marcapasso via toracoscopia e acesso intercostal é inovadora e representa uma potencial novidade terapêutica no tratamento de cavalos com arritmias cardíacas graves.

Palavras-chave:

arritmia; cardíaco; coração; ventrículo esquerdo; videocirurgia

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac arrhythmias are common in equine species and can be classified as either pathological or physiological (Van Loon, 2019). These include premature atrial and ventricular complexes, advanced second- and third-degree atrioventricular blocks, and atrial fibrillation (Van Loon, 2019). Diseases affecting the cardiac conduction system are primarily treated using antiarrhythmic drugs; however, these drugs are associated with significant adverse effects, high treatment costs, and in some cases, the possibility of arrhythmia recurrence following drug treatment (Sleeper, 2017; Van Loon, 2019). Additionally, there are some cases in which antiarrhythmic therapy is insufficient to resolve the clinical condition requiring the use of a cardiac pacemaker, such as third-degree atrioventricular block, advanced second-degree atrioventricular block, and atrial fibrillation, which pose a life-threatening risk to horses by causing syncope and sudden death (Navas de Solis, 2016; Van Loon, 2019).

In dogs, pacemaker implantation has been extensively studied and has been clearly demonstrated to be effective at resolving clinical signs associated with cardiac arrhythmias. As a result, pacemaker implantation enhances the quality of life and physical capacity (Lichtenberger et al., 2015). The transvenous endocardial approach is the preferred method for device implantation in dogs; however, it is not recommended for animals presenting with pre-existing infections, or when the risk of thrombotic complications can direct the surgeon to implant the pacemaker through the picardial stimulation technique (Deforge, 2019). Additionally, this condition can occur in patients presenting with cervical pyoderma, transvenous pacemaker infection, endocarditis, immunosuppressive therapy, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (Orton, 2019).

To the best of our knowledge, no previous publication has yet described the implantation of epicardial pacemakers in horses, while only one research group described a technique for transvenous endocardial pacemaker implantation (Van Loon et al., 2001). Furthermore, case reports of endocardial or epicardial pacemaker implantation assessed by thoracotomy in diseased horses are rare but have nevertheless reported promising results in the resolution of severe arrhythmia in horses (Pibarot et al., 1993; Petchdee et al., 2018; Sedlinská et al., 2021).

Development of new pacemaker implantation techniques would be a valuable therapeutic tool for horses with cardiac arrhythmias. Therefore, the present study aimed to develop and describe a technique for epicardial pacemaker implantation in horses using video surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number: 027/2021), in accordance with all laws and regulations governing the use of animal cadavers in scientific studies.

Five adult horse cadavers of various breeds, weights, and sexes, but all aged over 2 years, were used as models in this study. The horses used in this study were from the Large Animal Clinic and Surgery Service of the Veterinary Hospital of the Federal University of Paraná, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil. All animals were euthanized because of preexisting diseases. The exclusion criteria used in this study included the preexistence of cardiac diseases and absence of cardiac changes confirmed by clinical history and necropsy evaluations after the pacemaker implantation procedure. Individual characteristics of the animals used in this study are shown in Table 1. The animals were identified by numbers (1-5), following their sequence of participation in the study.

The patients had previously been euthanized with anesthesia, comprising 1 mg/kg xylazine and 0.05 mg/kg midazolam for sedation, and 2mg/kg ketamine for induction of general anesthesia. Following induction of anesthesia, an intrathecal injection of lidocaine was administered. Death was confirmed by cardiac auscultation.

After death, each animal was immediately transported to the surgical center, where it was placed on a surgical table in dorsal recumbency. Following correct positioning, the ventral region of the thorax over the sternum and the cranial region of the abdomen, as well as the left intercostal area between the 4th and 11th intercostal spaces (ICS), were shaved to better visualize the skin and musculature of these areas.

Characterization of horses used as a model for the development of the cardiac pacemaker implantation technique through thoracoscopy and intercostal access.

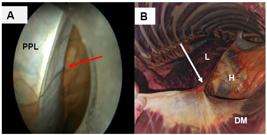

A 2-3 cm incision in the skin and subcutaneous tissue was made with a No. 24 blade scalpel, caudal to the manubrium, near the 18th right rib of the patient (Fig. 1A), followed by the introduction of an endotip trocar (11 mm) (Fig. 2B) at a 45° angle (Fig. 1B), which advanced through the abdominal musculature and pierced the diaphragm. After accessing the thorax, a rigid endoscope with a diameter of 10 mm and a working channel of 5 mm, Panoview Plus 0° (Fig. 2C), was introduced. A pair of 44 cm bariatric scissors (Fig. 2A) was inserted through the endoscope to perform pericardiotomy caudal to the cardiac apex, extending to the left side of the chest and facilitating access to the epicardium in this region. Pericardiotomy was performed according to the technique described by Lorga et al. (2023).

A second surgical access was created in the intercostal space to allow electrode insertion into the heart. Unipolar epicardial pacemakers (Myopore Unipolar, Greatbatch Medical, United States) were applied to conduct the study, and electrode fixation was performed using a specific fixation mechanism involving 10 clockwise rotational movements. The pacemaker electrode fixation procedure was performed through a 3 cm incision in the ICS on the ventral side of the left hemithorax, corresponding to the window of access to the heart (5th, 6th, and 7th ICS). The intercostal space for access was guided using a thoracoscope. After achievement of the intercostal access, an electrode fixation device was inserted and secured to the left heart apex.

A 5 cm muscular pocket (Figure 3 A, B) was created beneath the external oblique abdominal muscle to house the cardiac pacemaker generator. This pocket was created using a No. 24 scalpel, and the subcutaneous and muscular tissues in the region were dissected using blunt scissors. After the generator was inserted, the pocket was sutured with simple interrupted stitches using a nylon thread 0. Following completion of the procedure, the muscle and skin of the incisions made for the insertion of the single port and pacemaker in the intercostal space were approximated using nylon thread 0 and interrupted simple stitches. The duration of the surgical procedure and the difficulties associated with the technique were further recorded. Following pacemaker insertion, the animals were sent to the Pathology Department, where necropsy was performed, and a post-mortem macroscopic evaluation of the heart and adjacent organs was conducted.

Demarcation of the anatomical region and identification of the area for the abdominal incision to the insertion of the endoscope portal: (A) Red “X” indicates the exact area identified for the abdominal incision; (B) Insertion of the threaded trocar (endotip) into the abdominal cavity.

Materials used for the thoracoscopy procedure involving the implantation of pacemaker in the left ventricle in equines: (A)Panoview Plus 0° 10 mm endoscope (B) 11 mm threaded trocar (endodip); (C) 44 cm bariatric scissors.

Incision, insertion, and view of pacemaker implantation in a 28-year-old mixed-breed female equine: (A) Pocket created beneath the external oblique abdominal muscle to house the pacemaker generator; (B) Insertion of the generator in the region, revealing the appearance of the anatomical area at the end of the procedure (B).

The cadavers were positioned in right lateral recumbency, and the ribs were retracted to visualize the electrode fixation in the left ventricle. During necropsy, the diaphragm was preserved to observe incision size. After examination of the diaphragm, macroscopic evaluation of the heart and adjacent organs was performed to observe the presence of lesions resulting from the technique. The proportions of incisions in the pericardium, diaphragm, abdomen, and ICS were recorded using a ruler.

This noncomparative study describes a technique for epicardial pacemaker implantation through transdiaphragmatic and intercostal thoracoscopic access. The mean and standard deviation were obtained to determine the time and dimensions of the access required to perform the technique.

RESULTS

Animal 1 was used as for pilot tests of the thoracoscopy, pericardiotomy, and pacemaker fixation techniques. In this animal, pericardiotomy was initiated using a pair of hook scissors, followed by a pair of 44 cm blunt bariatric scissors. In this horse, we observed that the use of hook scissors caused damage to the epicardium, resulting in microlesions in the heart (Fig. 4). Therefore, its use was discontinued, and pericardiotomy was subsequently performed using only bariatric scissors in the remaining animals.

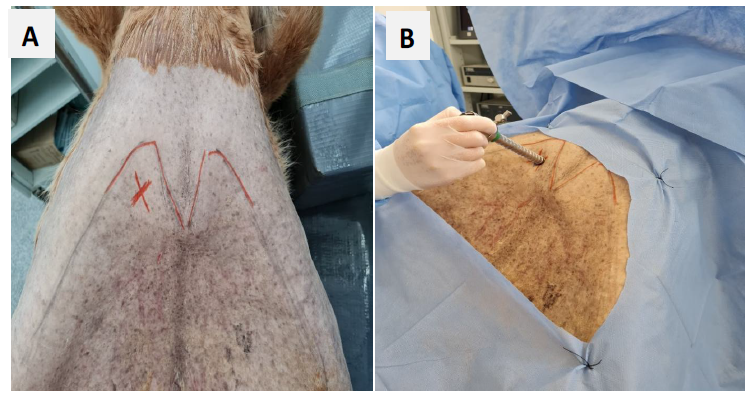

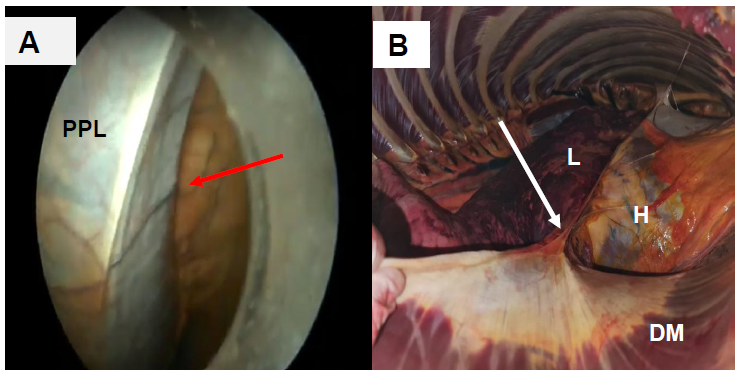

In animal 2, the phrenicopericardial ligament was promptly visualized (Fig. 5 A, B). This structure has a triangular shape facilitating pericardial incision, serving as a guide for pericardiotomy execution and improving its. This was possible because the ligament was distant from the heart, preventing the opening of the pericardial sac from occurring close to the epicardium, and avoiding iatrogenic injuries. The opening of the pericardial sac in animals 2, 3, 4, and 5 was performed through the phrenicopericardial ligament, thereby avoiding the induction of epicardial injury.

Adversities of little relevance for the pericardiotomy procedure, which did not interfere with the pacemaker implantation technique, but increased the surgical time were observed in two horses. These animals had the longest surgical times in the study. The increased surgical time in horse 4 was caused by the presence of adipose tissue covering the pericardium and the consequent need to dissect this tissue to allow adequate visualization of the phrenicopericardial ligament. After dissection, the ligament was visualized and pericardiotomy was performed without further complications.

In patient 5, greater proximity of the pericardial sac to the caudal left lung lobe was observed, limiting the size of the pericardiotomy. However, the pacemaker implantation technique was not impaired as it was not necessary to make an extensive incision in the pericardium to access the apex of the left ventricle.

The surgical access and video surgery instruments used to perform thoracoscopy via transdiaphragmatic access were effective in all animals in the experiment, allowing good manipulation of the pericardium and heart, and making it possible to fix the electrode to organs efficiently. None of the animals encountered difficulties in accessing the thorax through the diaphragm, which demonstrates that this is a reliable procedure requiring few surgical instruments.

Animal 1 had an endocardial pacemaker inserted into the epicardium at the left cardiac apex. The use of endocardial pacemakers was not successful because the material was fragile, and the electrode’s fixing region was short, resulting in inadequate attachment of the device to the epicardium. Therefore, we concluded that an epicardial pacemaker was the most appropriate for this experiment. An epicardial pacemaker was used in other animals, yielding satisfactory results, with good fixation of the device to the epicardium.

Superficial epicardial injury caused by pericardiotomy using Hook scissors in an adult male mixed-breed equine. The arrow indicates the site of the lesion.

Visualization of the phrenico-pericardial ligament of an adult mixed-breed mare: (A) Phrenic-pericardial ligament visualized during thoracoscopy as a reference for performing pericardiotomy prior to cardiac pacemaker implantation (red arrow); (B) aspect of phrenico-pericardial ligament identified during necropsy (white arrow).

To implant the endocardial pacemaker in horse 1, an electrode was inserted into the thorax through the endoscopic portal. In this case, intercostal access was not assessed, and the implanted pacemaker device was different from that used in the other patients. Therefore, the surgical time and size of the pericardiotomy were excluded from the calculations of the mean and standard deviation. However, the procedure for accessing the abdominal cavity and thoracoscopy was performed as in the other animals; therefore, the size of the horse’s abdominal incision was maintained to calculate the mean and standard deviation.

In all the animals, transdiaphragmatic access was made for portal passage, in addition to thoracoscopy and pericardiotomy. Following these procedures, a 3cm incision in the intercostal space in the lateral and ventral regions of the left hemithorax in patients receiving an epicardial pacemaker. Thoracoscopy revealed the location where access seemed most favorable to reach the region of interest in the heart through external digital palpation of the intercostal spaces. An intercostal incision was made, and the pacemaker applicator was introduced until the electrode tip reached the heart at the apex of the left ventricle, where it was fixed (Fig. 6 A, B, and C). The location of access through the intercostal space varied among the animals: in patient 4, it occurred at the 5th ICS; in patients 3 and 5, at the 6th ICS; and in patient 2, at the 7th ICS. In all cases, guiding intercostal access through video was effective in indicating the ICS at which the left apex of the heart could be successfully reached with the pacemaker applicator. It was possible to effectively fix the pacemaker electrodes in all horses.

In animal two, connective fatty tissue was observed in the thoracic cavity following incision of the intercostal space and access to the thorax. This tissue made it difficult to visualize and introduce the pacemaker applicator into the thorax; therefore, it was incised with bariatric scissors via thoracoscopy, allowing for good observation of the device inside the thorax. After fixing the pacemaker, the applicator was removed from the thorax, and a pouch was made between the external and internal abdominal oblique muscles in the left abdominal region near the end of the 18th rib for generator insertion. The device was placed and the skin of the thoracic and abdominal incisions was sutured to complete the technique.

The surgical times of the patients and the size of the incisions are shown in table 2 along with their mean and standard deviation values. The average surgical time for performing the technique in animals was 44 min. The incisions necessary for access to the abdomen, diaphragm, and intercostal space ranged from 2 to 3cm.

After the surgical procedures, all animals underwent necropsy for macroscopic observation of possible lesions in the thoracic and abdominal organs caused by the technique and the area of fixation of the pacemaker electrode. Only horse 1 presented with lesions on the epicardium due to the use of hook scissors for pericardiotomy; no lesions caused by the developed technique were found in the others. In all animals that underwent cardiac pacemaker implantation, the electrode was positioned at the left apex of the heart (Fig. 7). None of the patients exhibited cardiac abnormalities upon necropsy. No lesions were observed in the thoracic or abdominal organs.

DISCUSSION

Arrhythmia, which is common in horses, sometimes necessitates surgical treatment due to its association with severe clinical signs and risk of death (Navas de Solis, 2016; Van Loon, 2019). Clinical therapy with antiarrhythmic medications is the cornerstone of arrhythmia treatment in horses and is recommended when there are clinical signs or ventricular tachycardia (Sleeper, 2017; Redpath and Bowen, 2019). However, pharmacological treatment may be insufficient for some arrhythmias, and some brady arrhythmias may require pacemaker implantation for resolution (Sleeper, 2017; Redpath and Bowen, 2019; Van Loon, 2019).

The transvenous endocardial approach is preferred for device implantation because it is less invasive and causes fewer technique-related complications. However, it is not recommended for animals presenting with pre-existing infections, or those at risk of thrombotic complications, and only epicardial stimulation can be indicated by a cardiologist (Deforge, 2019). This condition is common in patients presenting with cervical pyoderma, transvenous pacemaker infection, endocarditis, immunosuppressive therapy, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (Orton, 2019). Horses are susceptible to thrombotic complications, and thrombophlebitis is the most common vascular disease in this species (Borghesan et al., 2018).

Few studies have investigated pacemaker use in horses, and few surgical approaches that enable heart access and device implantation have been described. In one such case endocardial pacemaker was implanted through a transvenous approach in a horse with bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome presenting with clinical intolerance to exercise. In this case, the animal had no postoperative complications, showed an improvement in quality of life, and no longer presented with exercise intolerance (Petchdee et al., 2018). Two case reports have further described the use of pacemakers to treat bradyarrhythmia in mules. Both animals had advanced second-degree atrioventricular block with syncope. In one case, the device was transvenously implanted into the endocardium through the right jugular vein into the right ventricle. In the other case, a bipolar epicardial pacemaker was positioned in the cardiac tissue through thoracotomy, accessing the sixth intercostal space, left ventricle, and atrium. The animal that received the epicardial pacemaker experienced some postoperative effects, including system malfunction necessitating device adjustment. The animal was treated with corticosteroids, and no further issues or arrhythmia recurrence was observed after 10 weeks, thereby resolving the clinical condition of the animal (Pibarot et al., 1993). In another case, a unipolar endocardial pacemaker was implanted in the right ventricle via transvenous access (Sedlinská et al., 2021). This patient experienced complications, including pacemaker displacement and infection of the subcutaneous pouch housing the generator, requiring new interventions. In the reported animal, the pacemaker was functional even 18 years after its implantation, and there was an improvement in the patient’s quality of life, with no cardiac remodeling or changes in the organs related to the surgery.

Presentation of the pacemaker electrode fixation in the left ventricle, implanted via thoracoscopy with transdiaphragmatic and intercostal access in a 17-year-old male mixed-breed equine: (A) insertion of the applicator into the thorax; (B) and (C) fixation of the pacemaker electrode to the left apex of the heart.

Measurements of incisions in centimeters (pericardium, diaphragm, abdomen, and intercostal space) and surgical time (minutes) necessary for the implantation of an epicardial cardiac pacemaker via thoracoscopy with transdiaphragmatic and intercostal access in adult equines of different breeds, sexes, and ages

Necropsy images (A) and (B) and thoracoscopic images (C) and (D) of the cardiac pacemaker electrode, implanted in adult male mixed-breed equines at the left cardiac apex through intercostal access with the aid of thoracoscopy, indicated by a white arrow, demonstrating its positioning in the organ.

Epicardial pacemaker implantation can be performed via thoracotomy and diaphragmatic access in humans and dogs, creating large openings in the diaphragm and intercostal spaces. In the present study, the developed technique aimed to be minimally invasive, using thoracoscopy, to avoid complications related to the open thoracotomy approach es described in horses or diaphragmatic access, which have not yet been reported for this species. Thoracotomy in horses is an invasive procedure that may lead to various complications, including pneumothorax, hemorrhage, hemothorax, and infection (Peroni, 2021). Additionally, to obtain complete access to the heart in horses, it is necessary to resect the fifth or sixth rib of the animal, or even remove both ribs. This procedure is invasive and can lead to many issues, such as a decrease in PaO2, in animals during the intraoperative period (Adler et al., 2021).

Thoracoscopy is a less invasive technique (Peroni, 2021), requiring minimal incisions to access the thoracic cavity and heart. In such cases, a single portal may be used for pericardiotomy. In the field of human medicine, various authors have described techniques for epicardial pacemaker implantation using thoracoscopy, including those that use the subxiphoid transdiaphragmatic approach (Papiashvilli et al., 2011; Jordan et al., 2013). Video thoracoscopic procedures, which involve smaller incisions and allow visualization of the thorax without spreading the ribs, are now an alternative to conventional thoracotomies for pacemaker implantation in medicine (Papiashvilli et al., 2011). Video surgery has several advantages over open thoracic access techniques, including minimal incision requirements, preservation of pulmonary function, reduced morbidity and mortality, absence of major surgical complications, and shorter surgical time (Papiashvilli et al., 2011, Nesher et al., 2014; Peroni, 2021).

Studies using thoracoscopy for epicardial pacemaker implantation have yielded excellent results. In an experimental study of piglets using intercostal and subxiphoid approaches, the authors observed that the procedure was effective, with no complications during or after surgery, demonstrating that it is a good method for pacemaker fixation (Jordan et al., 2013). Other studies have shown similar findings, in which thoracoscopy has proven to be a valuable tool for achieving success in fixing pacemaker electrodes and improving the clinical condition, both in the short and long term, of patients undergoing procedures, with minimal or no intraoperative and postoperative complications, asserting its effectiveness and safety over open techniques for device implantation (Jordan et al., 2013; Marini et al., 2020). This type of surgical approach for cardiac pacemaker implantation has never been described in equines.

In this experiment, the procedure proved promising, revealing that no injuries were induced to the tissues or organs adjacent to the heart during the technique. The pacemaker fixation to the epicardium was excellent, with a minimal surgical time, averaging 44 min. In a study using transvenous bipolar pacemakers transvenously in six horses, the time required for the procedure was 4 h (Van Loon et al., 2001). Considering that the total surgical time for all animals in this study was approximately 3 h, it was shorter than that of the cited authors. In a study in which the authors performed thoracotomy with rib resection for heart access, the average surgical time was 45 min, similar to this study. However, it should be noted that some animals in this study had shorter surgical times, and the authors took 45 min to access the heart and perform pericardiotomy; in this study, the average time to access the heart and perform pericardiotomy was about 22.5 minutes, a shorter time compared to the referred study (Adler et al., 2021). Additionally, pacemaker implantation in the heart involved performing additional procedures compared to the cited study. However, the surgical times remained similar.

In a reported case of pacemaker implantation via thoracotomy in a mule, no complications were observed during recovery, or in the immediate postoperative period. However, on the 4th day post-surgery, serohemorrhagic transudate was observed by echocardiography and thoracocentesis, which resolved after 10 days (Pibarot et al., 1993). In the animals studied, the developed technique did not pose any serious surgical risk, indicating that no significant injury occurred during the technique. Only one patient sustained injuries during the pericardiotomy, which were likely due to the use of hook scissors, which are associated with traumatic procedural characteristics. Another factor that may have predisposed the injuries is that this was the only animal in which pericardiotomy did not start at the phrenicopericardial ligament. This region is located further from the heart, allowing for a safer surgical approach.

Pericardiotomy is safe and does not induce significant physiological changes in the cardiocirculatory system of horses (Textor et al., 2006). Because this experiment was not related to diseases affecting the pericardium, the opening created in this membrane did not need to be excessively large; it should only be sufficient to allow access to the apex of the left ventricle of the heart. In this study, the average length of the pericardial incision in animals receiving the pacemaker was 16 cm, and access to the cardiac apex was achieved without difficulty in all animals. The size of these incisions varied among the animals, with the smallest being 12 cm and the largest being 20 cm. In all patients, the insertion of the electrode into the heart was performed quickly and effectively. In a case report describing the placement of an epicardial pacemaker in the left ventricle of a donkey, the size of the pericardiotomy was between 5 and 6 cm, performed longitudinally in the apex region, similar to this study. However, in the animals used in this study, the incision was made through the phrenicopericardial ligament, which was not observed in the present study (Pibarot et al., 1993). The fact that the pericardial opening was made via the phrenicopericardial ligament, and that manipulation of the heart and pericardial sac was performed by video surgery may have contributed to larger incisions by allowing complete access to the heart, facilitating visualization and manipulation of the organ.

In this study, postoperative complications were not observed as all procedures were conducted in cadavers. Despite this fact, the absence of significant lesions generated during the procedure, shorter surgical time compared to the use of access by thoracotomy, and the minimally invasive nature of the surgical method led us to infer that it will be safe and advantageous compared to open techniques when performed in live animals.

CONCLUSION

The epicardial pacemaker implantation technique using thoracoscopy with a transdiaphragmatic and intercostal approach is effective for fixing the pacemaker electrode to the hearts of adult horses. The technique proved to be minimally invasive, with a short surgical time, indicating its potential for treating arrhythmias in horses with significant rhythm disorders.

REFERENCES

- ADLER, D.M.T.; HOPSTER, K.; HOPSTER-IVERSEN, C. et al. Thoracotomy and pericardiotomy for access to the heart in horses: surgical procedure and effects on anesthetic variables. J. Equine Vet. Sci., v.96, p.103-315, 2021.

- BORGHESAN, A.C.; BARBOSA, R.G.; CERQUEIRA, N.F. et al. Evaluation of experimental jugular thrombophlebitis in horses treated with heparin. J. Equine Vet. Sci., v.69, p.59-65, 2018.

- DEFORGE, W.F. Cardiac pacemakers: a basic review of the history and current technology. J. Vet. Cardiol., v.22, p.40-50, 2019.

- JORDAN, C.P.; WU, K.; COSTELLO, J.P. et al. Minimally invasive resynchronization pacemaker: a pediatric animal model. Ann. Thorac. Surg., v. 96, p.2210-2213, 2013.

- LICHTENBERGER, J.; SCOLLAN, K.F.; BULMER, B.J.; SISSON, D.D. Long-term outcome of physiologic VDD pacing versus non-physiologic VVI pacing in dogs with high-grade atrioventricular block. J. Vet. Cardiol., v.17, p.42-53, 2015.

- LORGA, A. D.; GOMES, A.R.C.; STRUGAVA, L. et al. Pericardiotomy by transdiaphragmatic thoracoscopy singleport in horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci., v.127, p.104846, 2023.

- MARINI, M.; BRANZOLI, S.; MOGGIO, P. et al. Epicardial left ventricular lead implantation in cardiac resynchronization therapy patients via a video‐assisted thoracoscopic technique: long‐term outcome. Clin. cardiol., v.43, p.284-290, 2020.

- NAVAS DE SOLIS, C. Exercising arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in horses: review of the literature and comparative aspects. Equine Vet. J., v. 48, p.406-4013, 2016.

- NESHER, N.; GANIEL, A.; PAZ, Y. et al. Thoracoscopic epicardial lead implantation as an alternative to failed endovascular insertion for cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy. Innovations, v.9, p.427-431, 2014.

- ORTON, E.C. Epicardial pacemaker implantation in small animals. J. Vet. Cardiol., v.22, p.65-71, 2019.

- PAPIASHVILLI, M.; HAITOV, Z.; FUCHS, T.; BAR, I. Left ventricular epicardial lead implantation for resynchronisation therapy using a video-assisted thoracoscopic approach. Heart Lung Circ., v.20, p.220-222, 2011.

- PERONI, J. Complications of equine thoracic surgery. In: RUBIO-MARTINEZ, L.M.; HENDRICKSON D.A. (Eds.). Complications in equine surgery. New Jersy: Wiley Blackwell, 2021. p.491-497.

- PETCHDEE, S.; CHANDA, M.; CHERDCHUTHAM, W. Research article pacemaker implantation in horse with Bradycardia-Tachycardia Syndrome. Asian J. Anim. Vet. Adv., v.13, p.35-42, 2018.

- PIBAROT, P.; VRINS, A.; SALMON, Y.; DIFRUSCIA, R. Implantation of a programmable atrioventricular pacemaker in a donkey with complete atrioventricular block and syncope. Equine Vet. J., v. 25, p.248-251, 1993.

- REDPATH, A.; BOWEN, M. Cardiac therapeutics in horses. Vet. Clin. Equine Pract., v.35, p.217-241, 2019.

- SEDLINSKÁ, M.; KABEŠ, R.; NOVÁK, M. et al. Single-chamber cardiac pacemaker implantation in a donkey with complete AV Block: a long-term follow-up. Animals, v.11, p.746, 2021.

- SLEEPER, M.M. Equine cardiovascular therapeutics. Vet. Clin. North Am. Equine Pract., v. 33, p.163-179, 2017.

- TEXTOR, J.A.; DUCHARME, N.G.; GLEED, R.D. et al. Effect of pericardiotomy on exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension in the horse. Equine Comp. Exercise Physiol., v.3, p.45-51, 2006.

- VAN LOON, G. Cardiac arrhythmias in horses. Vet. Clin. North Am. Equine Pract., v.35, p.85-102, 2019.

- VAN LOON, G.; FONTEYNE, W.; ROTTIERS, H. et al. Dual‐chamber pacemaker implantation via the cephalic vein in healthy equids. J. Vet. Intern. Med., v.15, p.564-571, 2001.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

27 Jan 2025 -

Date of issue

Jan-Feb 2025

History

-

Received

29 Jan 2024 -

Accepted

10 Aug 2024

Transdiaphragmatic surgical access by thoracoscopy for epicardial pacemaker implantation in horses

Transdiaphragmatic surgical access by thoracoscopy for epicardial pacemaker implantation in horses

*PPL, phrenicopericardial ligament; H, heart; DM, diaphragm muscle; L, lung.

*PPL, phrenicopericardial ligament; H, heart; DM, diaphragm muscle; L, lung.