Abstract

The use of industrially manufactured elements for on-site installation has been recommended for the construction industry, although its application remains limited. The main barriers of off-site construction adoption, defined in this study as modular construction (MC), include the lack of technical knowledge, the need for innovative technologies, and the absence of well-defined business strategies. Well-structured business strategies can potentially enable the construction sector to gradually benefit from MC, aiming at reducing delays, improving project quality, controlling costs, and scaling production. This study aims to propose a theoretical framework for business strategies, which allow gradual MC adoption, based on integrating MC phases, product architecture, production strategy, and modular product platforms. A systematic literature review and qualitative meta-synthesis were conducted. The main theoretical contributions of this investigation consist of a set of fundamental concepts of MC and a theoretical framework that contains three business strategies to guide construction companies in adopting MC. From a practical perspective, these research results can help to improve construction managers' understanding of MC, helping them make strategic decisions related to its implementation.

Keywords

Modular construction; Production structure; Product architecture; Product platform; Business strategy

Resumo

A construção com elementos produzidos industrialmente e instalados no canteiro da obra vem sendo recomendada para a construção civil, embora sua aplicação ainda permaneça limitada. Entre os principais obstáculos à adoção da construção fora do canteiro de obra, definida neste estudo como construção modular (CM), destacam-se a falta de conhecimento técnico, a necessidade de tecnologias inovadoras e a ausência de estratégias de negócio bem definidas. Estratégias bem estruturadas permitem que o setor se beneficie gradualmente da CM, com ênfase na redução de prazos, maior qualidade do empreendimento, controle de custos e escalabilidade da produção. O objetivo desta pesquisa é propor uma estrutura teórica de estratégias de negócio para adoção gradual da CM, com base na associação e integração entre fases da CM, arquitetura do produto, estratégia de produção e plataformas de produtos modulares. Para isso, realizou-se uma Revisão Sistemática da Literatura e uma metassíntese qualitativa. Os resultados sintetizam os conceitos fundamentais da CM e apresentam uma estrutura teórica com três diferentes estratégias de negócio que orientam a adoção da CM por empresas de construção. De forma prática, a pesquisa contribui para uma melhor compreensão da CM por gestores, subsidiando-os no processo de tomada de decisões estratégicas sobre a sua implementação.

Palavras-chave

Construção modular; Estratégia de produção; Arquitetura de produto; Plataforma de produto; Estratégia de negócio

Introduction

Using off-site industrialized products has been widely recommended in the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) industry to enhance efficiency, rationalize the use of resources, improve quality, and make cost control more effective (Pan et al., 2020). However, traditional construction, characterized by on-site execution, remains predominant in AEC (Baek; Kim; Choi, 2024; Shahzad et al., 2023). By contrast, in certain European Countries, North America and Asia, adopting off-site construction is more common (Akinradewo et al., 2023). The manufacture of components, elements and volumetric modules by the manufacturing industry, in standardized and controlled processes, for later installation on-site, is considered an alternative to traditional construction (Wuni; Shen, 2020a; Wuni; Shen, 2022).

Existing literature presents a variety of terms related to off-site construction (Phillips; Guaralda and Sawang; 2016; Wuni; Shen; Antwi-Afari, 2023; Obi et al., 2023). However, different terminologies are often associated with different products and regional or national contexts. The main terminologies proposed in the literature are presented in Figure 1.

In this research, the term 'Modular Construction' (MC) refers to off-site construction, commonly used within the Brazilian national context. MC is regarded as an innovation that promotes a high degree of industrialization in construction processes, enabling more effective control over project definition, quality standards, deadlines, and construction-related costs (Brown; Sharma; Kiroff, 2020). It is characterized by modules produced off-site in a manufacturing plant, and installed on-site (Wuni; Shen; Antwi-Afari, 2023; Shahzad et al., 2023).

The concept of MC encompasses three key dimensions: product architecture, production strategy, and product platform. Product architecture refers to the configuration of production results, including its detailing and composition (Srisangeerthanan et al., 2020; Shahzad et al., 2023). Production strategy includes decisions related to processing equipment, manufacturing layout, automation level, production organization, and planning methods (Skinner, 1985).

In this research, the focus of the discussion on production strategy is oriented towards the customer order decoupling point, which concerns the stage when the customer is involved and contributes by defining and developing the product (Jansson; Johnsson; Engström, 2014). Product platforms are related to a set of resources, such as components, processes, knowledge, people and relationships, shared by different products of the same family (Robertson; Ulrich, 1998; Jansson; Johnsson; Engström, 2014).

Although MC application is recommended, some barriers still limit its adoption (Peltokorpi et al., 2018). The lack of technical knowledge and technologies, as well as the insufficient understanding of the supply chain and its implications for the design and construction process, contribute to the lack of confidence and objection for adopting MC in AEC and customers (Wuni; Shen, 2020a; Feldmann; Birkel; Hartmann, 2022; Ali et al., 2023a, 2023b; Martin et al., 2024; Wuni; Shen, 2022; Gao, 2022). Moreover, tools that facilitate implementation by integrating its key dimensions, which also structure business strategies, remain underexplored and poorly disseminated (Daget; Zhang, 2019).

In this research, business strategies are understood as an essential element for designing effective business models that promote competitive advantage for construction companies (Teece, 2010). Business strategies manage action plans for business growth, seeking to achieve market positioning, attract and satisfy customers, compete successfully, conduct operations, and achieve business objectives (Thompson; Gamble; Strickland, 2004). In addition, production strategies, business models, and organizational structures must be specifically designed to enhance MC benefits (Vásquez-Hernández; Alarcón; Pellicer, 2024).

It is recognized that a knowledge gap exists regarding guidelines for adopting business strategies capable of structuring MC implementation, thereby enabling AEC to gradually benefit from construction processes based on industrialized products. An in-depth examination of product architecture, production strategy, and product platform is therefore required to formulate business strategies that support gradual MC adoption. To address this knowledge gap, the study investigates the following questions:

-

Which are the key concepts underpinning the three core dimensions of MC: product architecture, production strategy, and product platform?

-

How can these concepts support the development of business strategies for MC adoption within the AEC?

The aim of this study is to propose a theoretical framework of business strategies for gradual MC adoption, based on the association and integration between MC phases, product architecture, production strategy and modular product platforms. To achieve this, a Systematic Literature Review (Kitchenham et al., 2009) and a qualitative meta-synthesis (Webster; Watson, 2002; Baker, 2016; Wuni; Shen, 2020b) were carried out. The main theoretical contributions of this investigation consist of a set of fundamental concepts of MC and a theoretical framework that contains three business strategies to guide construction companies in MC adoption. From a practical standpoint, the research results can contribute to construction managers' understanding of MC, helping them make strategic decisions related to its implementation.

Method

An understanding of the basic concepts of a subject is essential for developing research that contributes to the advancement of a given field (March; Smith, 1995). In this research, a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) was conducted to gather information to build and contextualize the theoretical basis of MC, as well as to formulate business strategies (Figure 2).

SLR is a secondary study based on relevant primary studies on a given subject (Tranfield; Denyer; Smart, 2003; Kitchenham et al., 2009; Snyder, 2019; Wohlin et al., 2022). SLR allows the evaluation and interpretation of relevant information to answer research questions, to build a new synthesis through a set of primary studies, using rigorous protocols (Kitchenham et al., 2009; Snyder, 2019). To do this, State of the Art "StArt" software was applied to analyse the SLR sample. StArt uses a protocolled process to analyze evidence obtained from a sample of publications, through an automating coding process, using qualitative and quantitative methods (Fabbri et al., 2016).

The SLR protocol is briefly structured into five main stages (Benitti, 2012; Aldieri et al., 2019):

-

definition of the research question and selection of databases;

-

identification of terms and string composition by combining keywords using Boolean operators;

-

application of refinement filters with well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria to enhance the accuracy and relevance of the information gathered;

-

identification of the relevant sample and full reading of the main sample; and

-

information synthesis and new knowledge building.

The stages in the development of this research are presented below:

-

the research question "Which are the key concepts underpinning the three core dimensions of MC: Product architecture, production strategy, and product platform? How can these concepts support the development of business strategies for MC adoption within the AEC?" Three databases were selected to search for primary studies: Scielo, Scopus, and Web of Science. Scielo was selected aiming to include local and regional academic papers that are evaluated by the criteria applied to journals indexed in the main databases. Scopus and Web of Science have a greater number of indexed journals and establish publication criteria with peer reviews, which support studies with quality information;

-

the combination of different terms covering MC, off-site, and prefabrication within the construction industry, and their variations, was used to compose search strings with Boolean operators, as shown in Figure 2;

-

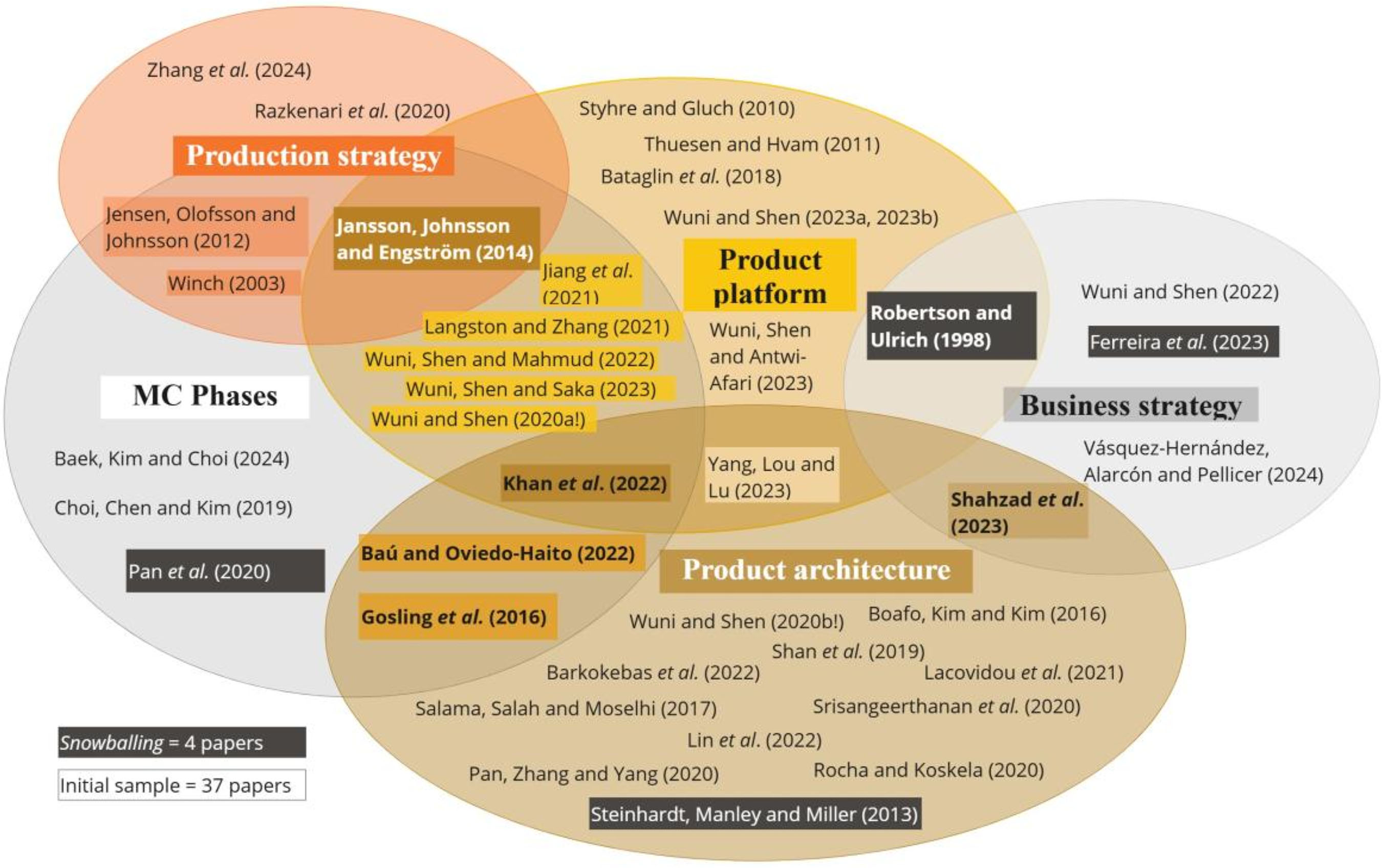

a total of 740 manuscripts were identified (Figure 2). Following a preliminary analysis of abstracts and removal of duplicates, 592 manuscripts were excluded. After full-text review, 107 additional manuscripts were removed as they did not provide relevant information on MC. Thus, 41 manuscripts made up the final sample, which contributed to the extraction of information for the construction of syntheses on MC and research results. Of these manuscripts, 4 were obtained through snowballing (Figure 3). Snowballing is a technique applied to gather publications not captured in the initial search in databases (Wohlin, 2014);

-

information on MC phases, product architecture, production strategies, product platform, and business strategy was collected and synthesized to build the knowledge base for strategy development; and

-

the analysis of the final sample identified intersections between the topics (Figure 3), highlighting references that overlap more than one topic. Subsequently, each of the analyzed topics was synthesized and presented through summaries and illustrations, facilitating both the understanding of the context and the comprehension of the processes involved.

For the formulation of the summaries, a meta-synthesis was developed (Wuni; Shen, 2020a). Meta-synthesis is an evidence-based qualitative research methodology applied to integrate, interpret, and reinterpret information about a specific subject, aiming to produce a new understanding from a critical and reflexive synthesis (Baker, 2016). This approach offers a structure that facilitates synthesis and associations between concepts of a given topic from different studies (Costanza; Ruth, 1998). Within the context of research, meta-synthesis supports integrating qualitative and quantitative results in a review, highlighting the intensity of the relationships between variables and the information provided by studies on a specific topic (Webster; Watson, 2002). Thus, in addition to the SLR stages, meta-synthesis characterizes and groups information through interconnected patterns and themes, for subsequent integrated interpretation and construction of a new understanding or theory (Wuni; Shen, 2020a).

For the development of the research meta-synthesis, the information collected from the SLR was organized into five topics, as shown in Figure 3. The collected information was interconnected to improve understanding by associating MC concepts with their organizational structure. An interpretative summary of the theoretical content underpinning the topic is provided in “Business strategy” item, at the end of each section.

The results of this analysis indicate a platform structure comprising different types of production and product strategies at different levels of MC application. Three business strategies are presented for each level of MC adoption, based on the company's objective for the level of MC adoption. The business strategies cover MC phases, product architecture, and production strategy, considering an approach with a greater or lesser degree of investment in different contexts of MC adoption.

Results and discussion

In order to implement MC through a business strategy, it is essential to analyze the MC configuration, and the procedures related to its application, following three key stages: defining the product architecture; defining the production strategy; and applying the product platform. Syntheses are provided at the end of each sub-section.

Stages of MC

The development of MC involves multiple phases, such as planning, contracting, design, production, assembly, transportation, installation, and maintenance (Choi; Chen; Kim, 2019). However, some studies summarize the phases into three main parts: manufacturing, assembly (which includes sub-assembly, non-volumetric and volumetric pre-assembly), and construction (Langston; Zhang, 2021). Another proposes: project (design and permits/approvals), pre-construction (planning and scheduling, engineering, module production, site preparation, floor slab execution), construction (delivery management, transport, move plan, assembly and installation), and post-construction (operation, module monitoring, and module reconfiguration) (Pan et al., 2020; Baú; Oviedo-Haito, 2022).

Synthesis - MC phases: based on the phases proposed in the literature, this research proposes five MC phases (Figure 4): project definition (planning, product architecture and logistics), manufacturing (production strategy, production and assembly), logistics (transport and route), construction (installation and site organization) and post-construction (use and maintenance).

Project definition

Planning - the process begins when the company or main contractor decides to implement MC in its projects (Jiang et al., 2021). MC planning is a fundamental activity in this phase (Gosling et al., 2016). To do this, an installation site is selected, analyzing the logistics for transporting and installing the modules, as well as the restrictions, project type, module units, degree of repetition and construction typology (residential, hotels, commercial, schools and offices) (Pan et al., 2020). Furthermore, the product platform is defined. In the bidding phase, the client may involve designers, engineering services, production, and consultants to define the project (Wuni; Shen; Mahmud, 2022). In addition, a more detailed planning and schedule is developed, defining the contractual model (Design-Bid-Build (DBB) or Design-Build (DB)) and the responsibility of the stakeholders (Pan et al., 2020).

Product architecture- after all approvals are completed, the project is defined according to production criteria (Khan et al., 2022). The evaluation of off-site production procedures and on-site execution enables early collaboration between the project consultants, the contractor, and the modular product supplier (Pan et al., 2020). The production strategy may or may not allow for a more participatory process, with greater flexibility for customization, or a product with controlled options from predefined production (Pan et al., 2020).

Logistics- the composition of the product is defined, considering constraints of the supply chain, such as logistical and construction feasibility. This involves analyzing the complexity of the project, on-site handling capacity, and access (Gosling et al., 2016). Furthermore, regulatory approval is required, considering the current standards applicable to MC (Khan et al., 2022).

Manufacturing

Production strategy- the product's production is then defined (Winch, 2003; Jensen; Olofsson; Johnsson, 2012; Jansson; Johnsson; Engström, 2014). Design changes are restricted during the production phase, as they could impact the entire production workflow (Khan et al., 2022). The engineering and production processes are validated in simulations that test the production flow, assembly, transport, and product installation (Pan et al., 2020). Product platform planning is also defined for this purpose.

Production- different types of production require different platforms. Platforms may be classified in two ways: one that allows product customization by the customer; and one that considers scalable production, where the customer only participates in selecting products available in the catalogue (Wuni; Shen, 2020a). Platform definition is contingent upon the prior definition of the project and the product.

Assembly- assembly and transport follow the production phase. Assumptions identified during the project definition and product manufacturing phases are considered (Wuni; Shen; Saka, 2023). Furthermore, the feasibility study and logistical data are validated to ensure greater consistency in determining the most viable implementation route.

Logistics

Transport and route- the modular products are sent to the site for installation according to the simulations and pre-established procedures (Wuni; Shen, 2020a). Thus, identifying traffic restrictions along the route and defining alternatives are necessary for greater accuracy in scheduling, control of movement flow, deadlines and logistics costs (Pan et al., 2020). Regarding environmental impact analyses, noise and air pollution should be considered (Pan et al., 2020).

Construction

Site organization - installing equipment with adequate capacity to move modules, such as cranes and racks, is essential. Optimizing preparation time, sequencing module installation, as well as levelling and paving of the base fixing points must align with the simulations conducted during the planning phase (Gosling et al., 2016).

Installation - installing modules requires experience, detailed knowledge of the site, adherence to dimensional tolerances, proper alignment, sequencing, and connection systems to ensure the necessary precision (Wuni; Shen; Saka, 2023). Monitoring on-site module installation, progress, and analyzing productivity allows professionals to develop continuously improved production and transport plans (Baek; Kim; Choi, 2024).

Post-construction

Use and maintenance – on-site installation marks the end of the MC stages (Khan et al., 2022). However, post-construction should also be considered. Analyzing component replacement procedures, maintenance and guidance is essential to ensure product performance throughout its life cycle (Peltokorpi et al., 2018). For maintenance, it is essential to consider the design aspects, including the inspection plan available in the owner's manual, refurbishment guidelines, procedures, appropriate tools, product availability and supply (Pan et al., 2020).

Product architecture

MC enables the independent generation of product parts, which can then be configured or integrated to form components, elements, or construction systems (Khan et al., 2022). Modularity can be applied at various levels within the architecture, depending on the product’s configuration and grouping (Gosling et al., 2016).

The variety and integration of modular products enable companies to increase product diversity through differentiated partitioning and grouping (Gosling et al., 2016). Consequently, product architecture plays a fundamental role in defining both the modularity of the product and its production strategy (Silva et al., 2024).

The modules are connected with different interfaces. Research presents three interface models: module-module; module-core; and module-podium (Shan et al., 2019; Srisangeerthanan et al., 2020; Shahzad et al., 2023; Rocha; Koskela, 2020). Interfaces can also be defined in slot, bus and sectional architecture (Peltokorpi et al., 2018).

The grouping and partitioning of a modular product (Figure 5) may be classified into different levels of hierarchical breakdown. Thus, a product can be divided into parts, these parts into subparts, and so forth (Rocha; Koskela, 2020). Different grouping levels can increase product variety, simplify production, and enable the outsourcing of certain product components (Rocha; Koskela, 2020).

Overview 1 - product architecture: module-module is designed to transfer the vertical load from the top module to the bottom module, as well as resisting the horizontal load from one module to the adjacent module. The slot and sectional interface consider connections between two modules, as defined in the module-to-module connection. However, slot and sectional present more details of this connection.

Synthesis 2 - product architecture: In the slot interface, it is understood that the component interfaces are differentiated, allowing a logical connection between them and limiting differentiated groupings. In the sectional interface, on the other hand, all the interfaces are identical, which allows greater flexibility in the connection between modules, thus enabling different arrangements.

Synthesis 3 - product architecture: the module-to-core connection is crucial for maintaining structural integrity and robustness, allowing effective load transfer from the modules to the central wall system. The bus interface is a feature of the module-to-core, with a connection to a common core via the same type of interface. It allows for variations in the location of components but is always linked to the core. Finally, the module-to-podium interface is designed to transfer the loads from the modules to the podium structure, which acts as the building's foundation.

MC configuration

The MC can be configured from subcomponents, components, elements and construction systems (Barkokebas et al., 2022), Figure 6. In addition, the MC is presented at different levels of connection and materiality, with a prefabricated, ready-made or furnished product (Yang; Lou; Lu, 2023).

According to Barkokebas et al. (2022), components correspond to integral units of a building system, characterized by geometry and defined functions, and consisting of a combination of elements, such as plates and profiles, and various materials, such as adhesives and mortars. Sub-components can be assembled completely or partially off-site and need to be integrated into structural building systems to form components such as beams, columns, chassis and frames (Lacovidou et al., 2021). However, they allow for more controlled production in terms of the quality of the final product (Baú; Oviedo-Haito, 2022).

Elements are conceived as constituent parts of the building that fulfil a specific function and can be comprise of a single component or a combination of components, or building materials (Barkokebas et al., 2022). The elements are available in the form of panels, roofs and volumes (connected panels, staircases, and other elements), fully or partially finished and ready to be installed (Steinhardt; Manley; Miller, 2013). In addition, they represent part of partially or completely finished products in the factory, including repeatable and scalable processes (Lin et al., 2022). Elements can be non-volumetric, 2D, generally unstructured (Wuni; Shen, 2020b), or volumetric, 3D, structured or unstructured, a characteristic that refers to the connection that links the different configurations (Gosling et al., 2016).

Elements such as insulated structural 2D panels, precast concrete panels and structural timber panels can be used to create 3D spaces or units, fully equipped and connected to an existing structure, such as bathrooms or kitchens (Boafo; Kim; Kim, 2016). The hybrid structure generally combines volumetric and non-volumetric components, such as 3D panels and modules, to form a single element (Pan; Zhang; Yang, 2020). The components and elements allow for customization in the design and execution phases, but require more joints, as well as more careful interfaces and alignments (Pan; Zhang; Yang, 2020).

The building system comprises interconnected components that perform specific functions in the building (Barkokebas et al., 2022). Building systems can consist of finished volumetric elements – ready and furnished 3D structural modules, that are grouped together to form complete prefabricated buildings (Salama; Salah; Moselhi, 2017).

Synthesis 4 - product architecture: the hierarchical structure of a modular product can be understood by its composition. A product is made up of the material, classified as a subcomponent; a component, made up of connected subcomponents; an element, which is the joining of components, usually found in the form of panels, roofs or volumes; and construction systems, which include the grouping of elements. This structure can also be classified into prefabricated products, in their simplest composition; pre-finished, when made up of materials in their final form; ready-molded, when finished and presenting connections ready for installation; and pre-furnished, when presented in their final form for use.

Production strategy

The definition of the production strategy adopted for MC is linked to the definition of the business strategy. Different types of production strategies can be identified in the production cycle, which influence the design and production of modules, as shown in Table 1.

Some authors highlight different types of production strategies, which allow for greater or lesser stakeholder participation in project definition, directly influencing modularity, production scalability, and customization (Winch, 2003; Rudberg, Wikner, 2004; Jensen; Olofsson; Johnsson, 2012; Jansson; Johnsson; Engström, 2014). A pre-existing design can be adjusted to the preferences of specific customers, resulting in the assembly of the product or the manufacture of components according to their requirements (Rudberg; Wikner, 2004). This process is defined as product customization (Jensen; Lidelöw; Olofsson, 2015).

Synthesis - production strategy: for each production strategy configuration, the extent to which production is based on customer requests or demand may vary, depending on the product architecture and platform adopted. Figure 7 illustrates how these configurations impact stakeholder input during project definition, considering the different phases of product customization, assembly and finalization. The transition point between forecast-based production and production based on the customer's order is called the customer order decoupling point (Jansson; Johnsson; Engström, 2014). This customer can be an agent in the supply chain, developers and construction companies or the end customer (user). However, when standardized modules are configured according to customer requirements, this is referred to as customized standardization (Rudberg; Wikner, 2004).

The production strategy plays a crucial role in determining the level of variety in each product design. In ETO strategies, for example, there is a lower degree of project predefinition, which leads to greater customer involvement in the development process and results in higher levels of product customization (Razkenari et al., 2020). On the other hand, companies that adopt CTO strategies tend to achieve greater scalability, as their end products are more standardized, which facilitate large-scale production and cost optimization (Razkenari et al., 2020).

Knowledge of the production strategy is essential, as it helps to define more flexible projects, whether in terms of layout, degree of modularity or the cost involved. This applies mainly to one-off projects, where customization is prioritized. For more scalable projects, the production strategy favors standardization and repeatability, ensuring greater control of costs, deadlines and quality (Dong et al., 2022).

Project management plays a crucial role in the success of MC projects, particularly due to the need for enhanced collaboration among stakeholders. Within this context, DB emerges as the suitable management method, as it promotes an integrated approach where design and construction are undertaken by a single entity, thereby facilitating coordination and communication (Razkenari et al., 2020). Furthermore, enhancing the MC supply chain requires a deep understanding of the drivers, opportunities, constraints, strategies, and necessary adaptations specific to each project context. This enables process optimization, reduces costs and timelines, and ensures that MC solutions are tailored to the specific needs of each project (Zhang et al., 2024).

Product platform

Product platforms enable the development and partial standardization of products, both shared elements that are not visible to the client, as well as customized, visible and valued components, such as finishes (Robertson; Ulrich, 1998; Jensen; Lidelöw; Olofsson, 2015). The MC product platform comprises the entire process, from the definition to the installation of the modular product, encompassing activities such as planning, engineering, manufacturing, transport, storage and on-site assembly (Wuni; Shen, 2020a). A product platform strategy comprises decisions about equipment used in the production process, factory layout, level of automation, organization of production and methods of planning and specifying the modular product design (Peltokorpi et al., 2018).

The platform approach to product development is presented through assets shared by a set of products. These assets can be divided into four categories (Robertson; Ulrich, 1998):

-

modular products - product composition, the accessories and tools needed for manufacture, production procedures and sequence, simulations and computer programs;

-

processes - definition of equipment to manufacture and assemble product components, the sequence of the production process, and the associated supply chain;

-

knowledge - know-how about the project, technological applications and limitations, production techniques, mathematical models, tests and simulations; and

-

people and relationships - teams, relationships between team members, stakeholder relationships with decision-makers (customers), and relationships with a network of suppliers.

MC is characterized by horizontal project construction, and independent in the factory, where production is conducted module by module, different from on-site vertical construction (Yang; Lou; Lu, 2023). However, MC requires the activities carried out in the factory, off-site, and construction on-site to be aligned. This requires efficient logistics management and reliable information exchange to ensure that the entire process, from manufacturing to installation, proceeds smoothly and without disruptions (Bataglin et al., 2018).

The typical configuration of relationships between people in MC comprises multidisciplinary stakeholders (Zhang et al., 2024). The team consists of clients (decision-makers), project manager, consultants, designers and engineers (project leaders) (Wuni; Shen; Saka, 2023), material suppliers, manufacturers (modular product), logistics service providers and site operators (module transporters) and builders (construction site managers and supervisors, operation managers, installers) (Wuni; Shen; Mahmud, 2022). In addition, academics and local governments can actively participate in MC production (Jiang et al., 2021).

In the production phase, various strategies can be adopted to optimize time management, equipment utilization, production processes, quality control, engineering efficiency, and costs for a given product family. A product family is a group of products with similar properties that can be derived from a common platform (Jensen; Lidelöw; Olofsson, 2015). Thus, differentiation and commonality plans are considered (Jansson; Johnsson; Engström, 2014).

The differentiation and commonality plan analyzes the common and distinct physical attributes of each product to address the specific needs and target value of different market segments (Robertson; Ulrich, 1998). Within this context, certain companies implement strategies that standardize non-visible components, such as the chassis, across different products, while customizing the more visible elements to cater to specific customer preferences (Styhre; Gluch, 2010; Thuesen; Hvam, 2011).

Different traditional construction design processes, the activities, processes and stages throughout MC production are interdependent and dynamic (Wuni; Shen, 2023b). Major decisions have direct implications for production, such as the failure to incorporate the project's manufacturing, transport and assembly constraints, which can lead to problems that are difficult to resolve in subsequent stages (Wuni; Shen, 2023b). In addition, the information gap between production engineers and designers can result in inaccurate specifications of the interfaces between modules, reduced manufacturing capacity for the project and inadequate division of modules (Wuni; Shen, 2023a).

The organizational dimension requires the early involvement of key stakeholders, with effective communication and information sharing, as well as coordination through technological solutions and simulations (Wuni; Shen, 2023a), which offers opportunities for significant contributions to design information (Wuni; Shen; Antwi-Afari, 2023). Depending on the production strategy adopted, the relationship and collaboration between each of the stakeholders vary, where the intensity of the relationships is mainly impacted by the timing of the customer's entry into the product development process (Peltokorpi et al., 2018). Thus, it is essential that the design team develop it based on local technical standards, which can guide detailed modular solutions (Wuni; Shen; Antwi-Afari, 2023). The product platform also offers flexibility in the post-construction phase by developing assets and capabilities that relate to the products during use (Peltokorpi et al., 2018).

Synthesis 1 - product platform: Figure 8 presents the product platform proposed in this research, based on product architecture, production strategy and organizational form. It shows the levels of product grouping and partitioning, the type of architecture that covers each level, and the production strategy that can be linked to each of these levels and products. In addition, the organization that characterizes the client's actions within the process, according to the production strategy, is also presented.

A product platform geared towards Level 1 production focuses on developing products based on the specific needs of customers, both participatory and non-participatory, which requires precise feasibility studies. At this level, both fully customized products and those with specific variations are considered. On the other hand, at levels 2 and 3, products with predefined options predominate. In this case, the scalable production of modular, unfinished components and elements makes it possible to configure different solutions while maintaining a certain degree of customization, especially in the final finishes. Level 4 refers to the production and availability of finished products, fully completed in the factory. At this stage, there is little customer interference in the process of defining the final product.

Synthesis 2 - product platform: The platform demonstrates that, under production strategies involving higher customer participation, products are more extensively partitioned into components and subcomponents to accommodate their uniqueness. Consequently, production occurs at a minimal scale and is customized for individual products. On the other hand, pre-defined products can incorporate levels 1, 2, and 3 of partitioning and grouping, with unfinished elements representing the most complete form of prefabrication. This approach allows customers to participate in the final product definition by providing a wider range of options to choose from. Finally, stocked products, determined based on market feasibility studies, can encompass all levels of partitioning, where ready-made building systems (level 4) are the least common due to their high stocking costs and increased risk of product obsolescence.

Business strategy

The relationship between production strategy, product architecture and product platform are crucial for defining business strategy propositions. When developing their products, companies seek a competitive advantage by offering high-quality products that are easy to produce and attractively priced for potential buyers, while at the same time eliminating waste in production (Silva et al., 2024). Thus, the decision to adopt MC should be made after systematically analyzing the production strategy best suited to the company's business goals and objectives (Shahzad et al., 2023).

The feasibility study, with a detailed analysis of the determining factors of customers and the actions of stakeholders, is essential for decision-making on adopting MC (Wuni; Shen, 2022). Within this context, defining the business strategy is fundamental to implementing MC projects.

Business models are concepts that can be used as tools to describe and analyze the business logic for adopting MC (Vásquez-Hernández; Alarcón; Pellicer, 2024). It may be oriented either toward the type of product, as is the case with MC, which focuses on products involving architectural concepts and production strategy, or toward processes, which clearly define their phases and, consequently, the ideal platform.

Business strategies are based on four axes: architecture (product), production strategy (customer participation), phases (definition, production, assembly, installation and maintenance) and the product platform (Vásquez-Hernández; Alarcón; Pellicer, 2024). The platform can enable product variability through a common platform, focusing on optimizing costs and schedules, as well as providing design solutions according to the customer's needs (Robertson; Ulrich, 1998).

In the research carried out by Ferreira et al. (2023), business strategies were proposed. Projects that adopt flexibility as a strategy typically offer products with fixed modules, developed with low mechanization, and avoid investing in highly specialized equipment due to product variability (Ferreira et al., 2023). In contrast, companies prioritizing productivity rely on standardized processes and products, characterized by repetitive activities that facilitate the acquisition of automated equipment and the adoption of a line production system (Ferreira et al., 2023). Investment in specialized equipment is essential to successfully implement this productivity-focused strategy.

In the research by Peltokorpi et al. (2018), modularization strategies were proposed based on the primary objectives of construction investments, organized into three axes:

-

design (innovative design solutions);

-

construction (quality, cost reduction, and shortened deadlines); and

-

use (flexibility in use and maintenance).

These strategies were further divided into four dimensions:

-

organizational structure;

-

product architecture (which includes the production strategy);

-

production system (which defines the product modularity); and

-

platform assets used (Peltokorpi et al., 2018).

Companies develop their strategies based on these three axes, allocating the dimensions according to the scenario that best fits their needs.

Synthesis 1 - business strategy: for this research, a theoretical framework is proposed, which highlights the product platform, with its catalysts, for three different business strategies (Figure 8). These elements are presented in Table 2, considering the concepts presented by Robertson and Ulrich (1998), Vásquez-Hernández, Alarcón, and Pellicer (2024), along with the strategies proposed by Peltokorpi et al. (2018) and Ferreira et al. (2023). The table also includes an analysis of the phases of MC, its product architecture, and production strategy.

Figure 9 shows the relationship among the MC phases, product architecture, production strategy and, consequently, the definition of the product platform according to the business strategy. The structure considers the evolution of MC adoption through the product developed, from its simplest to its most complete specification.

Business strategy 1: companies seeking to minimize initial investment can adopt a more flexible business strategy focused on unique and personalized projects, where product definition involves significant customer input and relies less on industrialized systems. However, this strategy entails greater risk and higher costs for both the company and the customer, due to uncertainties in product definition and the need for specific project adjustments. These production strategies employ lower levels of grouping, as sub-components, components, and non-volumetric elements must be combined to create complete elements that precisely meet customer requirements.

Business strategy 2: companies engaged in intermediate processes, aiming for a more direct relationship with customers, can adopt a business strategy focused on cost, time, and quality. In this strategy, the variety of products available in the market enables customers to explore more personalized options, particularly regarding finishes, thereby enhancing perceived customer value. However, to ensure customization aligns with customer expectations, frequent feasibility studies are essential. These studies help anticipate shifts in customer preferences and allow production to be adjusted efficiently, minimizing risks and additional costs. By combining standardization and customization, the company can offer products that balance both flexibility and efficiency.

Business strategy 3: companies with greater initial investment capacity can adopt a use-oriented strategy centered on pre-defined and stocked products. This approach facilitates straightforward replacement of components and modules, providing greater predictability in costs and timelines. However, project customization options tend to be more limited, depending on product availability in the market and the flexibility to adapt the project based on existing stock. While this strategy can be applied across all levels of grouping, stocked options for structured volumetric elements and complete building systems are less common due to the higher costs associated with stocking management of these modules.

Conclusion

The research has presented the various dimensions involved in MC, covering its phases, product architecture, production strategy, and product platforms, all of which can be applied to enhance production processes. Understanding and defining the business strategy, based on the interplay between these MC dimensions, facilitates deeper insight into the process and supports the optimization of strategies for MC implementation by companies.

The theoretical framework on business strategies offers a synthesized set of principles for gradual MC adoption, articulating product architecture, production strategy, and the catalysts that promote its application, as emphasized in the summaries corresponding to each level. The investments needed to adopt MC vary according to the different business strategies. This process involves changes in the market and in production, as well as promoting greater competitiveness between companies in the sector.

MC adoption can start with business strategies that demand lower initial investment, such as production based on customer orders, which allows the combination of on-site systems with modular components sourced from suppliers. Over time, the business strategy can evolve towards production with greater foresight and increased customer involvement. Purchasing volumetric elements and construction systems from suppliers can limit a company’s ability to meet specific project requirements. Consequently, many companies choose to establish their own factories and verticalize production. These strategies demand higher investment to manufacture and assemble modules. Ensuring business viability and scalability is essential for successfully transitioning to this new paradigm.

The research contributes to existing knowledge by systematically presenting the context of MC, thereby supporting decision-making for companies seeking a more structured approach to adopting MC. Additionally, it helps to disseminate MC practices across diverse production scenarios. Ongoing assessments are required in real contexts, such as Brazil, considering the unique features of its market and infrastructure. Through additional analyses, strategies may be further refined and adapted to suit specific regional conditions. In summary, the study underscores the significance of fostering MC application in the construction industry, focusing on innovation, implementation, and production control, and promoting greater flexibility in the maintenance of the resulting products.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Universidade de São Paulo - USP [Process: 22.1.09345.01.2], Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) [Process: 88887.994483/2024-00], and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPQ) [Process: 421370/2023-8; 314760/2023-7] for their generous funding support.

Declaração de Disponibilidade de Dados

Os dados de pesquisa estão disponíveis no corpo do artigo.

References

- AKINRADEWO, O. et al. Modular method of construction in developing countries: the underlying challenges. International Journal of Construction Management, v. 23, n. 8, p. 1344–1354, jun. 2023.

- ALDIERI, L. et al. Environmental innovation, knowledge spillovers and policy implications: A systematic review of the economic effects literature. Journal of Cleaner Production, v. 239, p. 118051, Dec. 2019.

- ALI, A. H. et al. Exploring stationary and major modular construction challenges in developing countries: a case study of Egypt. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology, v. ahead-of-print, jan. 2023a.

- ALI, A. H. et al. Identifying and assessing modular construction implementation barriers in developing nations for sustainable building development. Sustainable Development, v. 31, n. 5, p. 3346–3364, 2023b.

- BAEK, J.; KIM, D.; CHOI, B. Deep learning-based automated productivity monitoring for on-site module installation in off-site construction. Developments in the Built Environment, v. 18, p. 100382, abr. 2024.

- BAKER, J. D. The purpose, process, and methods of writing a literature review. AORN journal, v. 103, n. 3, p. 265–269, mar. 2016.

- BARKOKEBAS, B. et al. Glossário da aliança construção modular São Paulo: Aliança da Construção Modular, 2022.

- BATAGLIN, F. S. et al. BIM 4D aplicado à gestão logística: implementação na montagem de sistemas pré-fabricados de concreto engineer-to-order Ambiente Construído, Porto Alegre, v. 18, n. 1, p. 173–192, jan./mar. 2018.

- BAÚ, G.; OVIEDO-HAITO, R. J. J. Mapping activities and inputs of modular construction with steel 3D modules in Brazil. In: IOP CONFERENCE SERIES: EARTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE, Montréal, 2022. Proceedings […] Montréal, 2022.

- BENITTI, F. B. V. Exploring the educational potential of robotics in schools: A systematic review. Computers & Education, v. 58, n. 3, p. 978–988, Apr. 2012.

- BOAFO, F. E.; KIM, J.-H.; KIM, J.-T. Performance of Modular Prefabricated Architecture: Case Study-Based Review and Future Pathways. Sustainability, v. 8, n. 6, p. 558, jun. 2016.

- BROWN, G.; SHARMA, R.; KIROFF, L. Insights into the New Zealand Prefabrication Industry. In: INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE ARCHITECTURAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION, 54., Auckland, 2020. Proceedings […] Auckland, 2020.

- CHOI, J. O.; CHEN, X. B.; KIM, T. W. Opportunities and challenges of modular methods in dense urban environment. International Journal of Construction Management, v. 19, n. 2, p. 93–105, mar. 2019.

- COSTANZA, R.; RUTH, M. Using dynamic modeling to scope environmental problems and build consensus. Environmental Management, v. 22, n. 2, p. 183–195, mar. 1998.

- DAGET, Y. T.; ZHANG, H. Decision-making model for the evaluation of industrialized housing systems in Ethiopia. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, v. 27, n. 1, p. 296–320, jan. 2019.

- DONG, C. et al. Research on fine scheduling and assembly planning of modular integrated building: a case study of the Baguang International Hotel project. Buildings, v. 12, n. 11, p. 1892, nov. 2022.

- FABBRI, S. et al. Improvements in the StArt tool to better support the systematic review process. In: INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT IN SOFTWARE ENGINEERING, 20., New York, 2016. Proceedigns […] New York, 2016.

- FELDMANN, F. G.; BIRKEL, H.; HARTMANN, E. Exploring barriers towards modular construction: a developer perspective using fuzzy DEMATEL. Journal of Cleaner Production, v. 367, p. 133023, set. 2022.

- FERREIRA, C. T. et al. Business model and customization in modular construction in the UK: In: ZERO ENERGY MASS CUSTOM HOME INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE, 10., Arequipa, 2023. Proceedings […] Arequipa, 2023.

- GAO, A. Characteristics and application of modular integrated construction. Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology, v. 28, p. 206–212, dez. 2022.

- GOSLING, J. et al. Defining and categorizing modules in building projects: an international perspective. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, v. 142, n. 11, p. 04016062, nov. 2016.

- JANSSON, G.; JOHNSSON, H.; ENGSTRÖM, D. Platform use in systems building. Construction Management and Economics, v. 32, n. 1/2, p. 70–82, fev. 2014.

- JENSEN, P.; LIDELÖW, H.; OLOFSSON, T. Product configuration in construction. International Journal of Mass Customisation, v. 5, n. 1, p. 73–92, 2015.

- JENSEN, P.; OLOFSSON, T.; JOHNSSON, H. Configuration through the parameterization of building components. Automation in Construction, v. 23, p. 1–8, 2012.

- JIANG, Y. et al. Blockchain-enabled cyber-physical smart modular integrated construction. Computers in Industry, v. 133, p. 103553, dez. 2021.

- KHAN, A. et al. Drivers towards adopting modular integrated construction for affordable sustainable housing: a Total Interpretive Structural Modelling (TISM) Method. Buildings, v. 12, n. 5, p. 637, may 2022.

- KITCHENHAM, B. et al. Systematic literature reviews in software engineering: a systematic literature review. Information and Software Technology, v. 51, n. 1, p. 7–15, Jan. 2009.

- LACOVIDOU, E. et al. Digitally enabled modular construction for promoting modular components reuse: A UK view. Journal of Building Engineering, v. 42, p. 102820, out. 2021.

- LANGSTON, C.; ZHANG, W. DfMA: Towards an integrated strategy for a more productive and sustainable construction industry in Australia. Sustainability, v. 13, n. 16, p. 9219, jan. 2021.

- LIN, T. et al. Offsite construction in the Australian low-rise residential buildings application levels and procurement options. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, v. 29, n. 1, p. 110–140, jan. 2022.

- MARCH, S. T.; SMITH, G. F. Design and natural science research on information technology. Decision Support Systems, v. 15, n. 4, p. 251–266, dez. 1995.

- MARTIN, H. et al Validating the Relative Importance of Technology Diffusion Barriers– Exploring Modular Construction Design-Build Practices in the UK. International Journal of Construction Education and Research, v. 21, n. 1, p. 3–23, 2024.

- OBI, L. I. et al. Establishing interrelationships and dependencies of critical success factors for implementing offsite construction in the UK. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, ahead-of-print, 2023.

- PAN, W. et al. Modular integrated construction for high-rises: measured success. Hong Kong: The University of Hong Kong, 2020.

- PAN, W.; ZHANG, Z.; YANG, Y. Briefing: Bringing clarity and new understanding of smart and modular integrated construction. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Smart Infrastructure and Construction, v. 173, n. 1, p. 175–179. 2020.

- PELTOKORPI, A. et al. Categorizing modularization strategies to achieve various objectives of building investments. Construction Management and Economics, v. 36, n. 1, p. 32–48, 2018.

- PHILLIPS, D.; GUARALDA, M.; SAWANG, S. Innovative housing adoption: Modular housing for the Australian growing family. Journal of Green Building, v. 11, n. 2, p. 147–170, 2016.

- RAZKENARI, M. et al. Perceptions of offsite construction in the United States: An investigation of current practices. Journal of Building Engineering, v. 29, p. 101138, may 2020.

- ROBERTSON, D.; ULRICH, K. Planning for product platforms. Sloan Management Review, v. 39, n. 266, p. 19–31, jul. 1998.

- ROCHA, C. G. da; KOSKELA, L. Why is product modularity underdeveloped in construction? In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 25., Berkeley, 2020. Proceedings […] Berkeley, 2020.

- RUDBERG, M.; WIKNER, J. Mass customization in terms of the customer order decoupling point. Production Planning & Control, v. 15, n. 4, p. 445–458, 2004.

- SALAMA, T.; SALAH, A.; MOSELHI, O. Integration of offsite and onsite schedules in modular construction. In: INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON AUTOMATION AND ROBOTICS IN CONSTRUCTION, 34., Taipei, 2017. Proceedings […] Taipei, 2017.

- SHAHZAD, W. M. et al Benefits, constraints and enablers of modular offsite construction (MOSC) in New Zealand high-rise buildings. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, v. 31, n. 10, p. 4042–4061, Apr. 2023.

- SHAN, S. et al. Engineering modular integrated construction for high-rise building: a case study in Hong Kong. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Civil Engineering, v. 172, n. 6, p. 51–57, nov. 2019.

- SILVA, M. H. B. da et al Insertion of modular construction aligned with lean principles: a conceptual map model. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 32., Auckland, 2024. Proceedings […] Auckland, 2024.

- SKINNER, W. Manufacturing: the formidable competitive weapon New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1985.

- SNYDER, H. Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, v. 104, p. 333–339, nov. 2019.

- SRISANGEERTHANAN, S. et al. Review of performance requirements for inter-module connections in multi-story modular buildings. Journal of Building Engineering, v. 28, p. 101087, mar. 2020.

- STEINHARDT, D. A.; MANLEY, K.; MILLER, W. Reshaping housing: the role of prefabricated systems. University of Technology, 2013.

- STYHRE, A.; GLUCH, P. Managing knowledge in platforms: boundary objects and stocks and flows of knowledge. Construction Management and Economics, v. 28, n. 6, p. 589–599, jun. 2010.

- TEECE, D. J. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Planning, v. 43, n. 2–3, p. 172–194, abr. 2010.

- THOMPSON, A. A.; GAMBLE, J. E.; STRICKLAND, A. J. Strategy: winning in the marketplace: core concepts, analytical tools, cases. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

- THUESEN, C.; HVAM, L. Efficient on‐site construction: learning points from a German platform for housing. Construction Innovation, v. 11, n. 3, p. 338–355, jan. 2011.

- TRANFIELD, D.; DENYER, D.; SMART, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, v. 14, n. 3, p. 207–222, 2003.

- VÁSQUEZ-HERNÁNDEZ, A.; ALARCÓN, L. F.; PELLICER, E. Business models emerging from industrialized construction adoption. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 32., Auckland, 2024. Proceedings […] Auckland, 2024.

- WEBSTER, J.; WATSON, R. T. Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: writing a literature review. MIS Quarterly, v. 26, n. 2, p. xiii–xxiii, 2002.

- WINCH, G. Models of manufacturing and the construction process: the genesis of re-engineering construction. Building Research & Information, v. 31, n. 2, p. 107–118, jan. 2003.

- WOHLIN, C. Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. In: INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT IN SOFTWARE ENGINEERING, 18., New York, 2014. Proceedings […] New York, 2014.

- WOHLIN, C. et al Successful combination of database search and snowballing for identification of primary studies in systematic literature studies. Information and Software Technology, v. 147, p. 106908, Jul. 2022.

- WUNI, I. Y.; SHEN, G. Q. Barriers to the adoption of modular integrated construction: Systematic review and meta-analysis, integrated conceptual framework, and strategies. Journal of Cleaner Production, v. 249, p. 119347, mar. 2020b.

- WUNI, I. Y.; SHEN, G. Q. Critical success factors for modular integrated construction projects: a review. Building Research & Information, v. 48, n. 7, p. 763–784, out. 2020a.

- WUNI, I. Y.; SHEN, G. Q. Exploring the critical production risk factors for modular integrated construction projects. Journal of Facilities Management, v. 21, n. 1, p. 50–68, jan. 2023b.

- WUNI, I. Y.; SHEN, G. Q. Exploring the critical success determinants for supply chain management in modular integrated construction projects. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, v. 12, n. 2, p. 258–276, jan. 2023a.

- WUNI, I. Y.; SHEN, G. Q. P.; MAHMUD, A. T. Critical risk factors in the application of modular integrated construction: a systematic review. International Journal of Construction Management, v. 22, n. 2, p. 133–147, mar. 2022.

- WUNI, I. Y.; SHEN, G. Q. Towards a decision support for modular integrated construction: an integrative review of the primary decision-making actors. International Journal of Construction Management, v. 22, n. 5, p. 929–948, abr. 2022.

- WUNI, I. Y.; SHEN, G. Q.; ANTWI-AFARI, M. F. Exploring the design risk factors for modular integrated construction projects. Construction Innovation, v. 23, n. 1, p. 213–228, jan. 2023.

- WUNI, I. Y.; SHEN, G. Q.; SAKA, A. B. Computing the severities of critical onsite assembly risk factors for modular integrated construction projects. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, v. 30, n. 5, p. 1864–1882, jan. 2023.

- YANG, Z.; LOU, J.; LU, W. Lean modular integrated construction manufacturing: operation based production process optimization. In: EUROPEAN CONFERENCE ON COMPUTING IN CONSTRUCTION; INTERNATIONAL CIB W78 CONFERENCE, 40., Heraklion, 2023. Proceedings […] Heraklion, 2023.

- ZHANG, Y. et al. Enhancing modular construction supply chain: Drivers, opportunities, constraints, concerns, strategies, and measures. Developments in the Built Environment, v. 18, p. 100408, abr. 2024.

Edited by

-

Editor:

Carlos Torres Formoso

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

03 Nov 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

17 Jan 2025 -

Accepted

27 May 2025

Strategic perspectives for modular construction adoption

Strategic perspectives for modular construction adoption

Source: based on

Source: based on  Source: based on

Source: based on  Source: based on

Source: based on  Source: based on

Source: based on