Abstract

Cool tiles are more durable and resistant roofing materials and have high solar reflectance, therefore, their surfaces have lower temperatures compared to conventional tiles. Thus, the objective was to evaluate the reflective behavior and thermal performance of cool tiles that are available in the Brazilian market considering that these data are not available. To achieve that, the color parameters and the spectral reflectance of seven cool concrete and fiber cement tiles were measured and their surface temperatures were monitored during the period of greatest sun exposure on a hot and dry day in the city of São Carlos, in the state of São Paulo. The cool tiles of darker colors, despite the reflective coating, are the most heated even compared to conventional finishing tiles. White tiles have better reflective performance and have presented the lowest surface temperatures because of the higher reflectances in the visible region due to their coloration. Despite this, the near infrared is the spectral region with the highest predicted surface temperature reduction, which was confirmed in the Pearson correlation analyzes that were performed with the thermal camera and the infrared thermometer used in the surface temperature measurement.

Keywords

Cool tiles; Solar reflectance; Surface temperature; Thermal performance

Resumo

Telhas frias são materiais de cobertura mais duráveis e resistentes e possuem alta refletância solar, portanto, suas superfícies apresentam menores temperaturas com relação a uma telha convencional. Dessa forma, o objetivo foi avaliar o comportamento refletivo e desempenho térmico de telhas frias que estão disponíveis no mercado brasileiro tendo em vista que esses dados não estão disponíveis. Para isso, foram medidos os parâmetros de cor e a refletância espectral de sete telhas de concreto e fibrocimento frias e monitoradas as suas temperaturas superficiais no período de maior exposição solar num dia quente e seco na cidade de São Carlos, SP. As telhas frias de cores mais escuras, apesar do revestimento refletivo, são as mais aquecidas mesmo comparadas as telhas de acabamento convencional. As telhas brancas possuem melhor desempenho refletivo e apresentaram as menores temperaturas superficiais por causa das maiores refletâncias na região visível devido à sua coloração. Apesar disso, o infravermelho próximo é a região espectral com previsão de maior redução de temperatura superficial, o que foi confirmado nas análises de correlação de Pearson que foram realizadas com a câmera térmica e o termômetro de infravermelho utilizados na medição de temperatura superficial.

Palavras-chave

Telhas frias; Refletância solar; Temperatura superficial; Desempenho térmico

Introduction

In single-storey buildings, the higher incidence of solar radiation, due to the greater zenith angles of the solar trajectory, contributes to the greater solar intensity on horizontal surfaces (Frota; Schiffer, 2001). Therefore, the roof is the system that receives the most thermal energy from the Sun. In this sense, roofing materials called reflective or cool have high values of solar reflectance, that is, they heat less than a conventional surface with the same finish and so contribute to the reduction of surface temperature (Shirakawa, 2020).

Roof tiles have advantages fire safety, mechanical durability, and they generally offer improved air circulation on both their upper and lower faces (Synnefa; Santamouris, 2012). Ferrari et al. (2015) also mention the greater resistance to weathering and natural aging of ceramic tiles compared to polymeric materials that suffer damage when exposed to ultraviolet radiation, but which currently dominate the cool building materials market.

Studies were developed with the addition of colored near-infrared reflective pigments on the tile substrate to maximize solar reflectance gains and reduce the surface temperature in asphalt shingles and concrete tiles in Levinson et al. (2010) and ceramic tiles in Pisello et al. (2013) and Ferrari, Muscio and Siligardi (2016). In an experiment performed by Rosado et al. (2014) in two adjacent and similar houses in the Central Valley of California, on a summer day, reductions in the roof maximum surface temperature with cool concrete tiles on the upper and lower face were observed, in this order, by 13.8 ºC and 14.3 ºC in relation to the asphalt shingle of the standard house, and a decrease of 10.5 ºC in the attic air temperature, which resulted in energy savings for cooling of 10.7 kWh/m2 per roof area for the period of one year.

In Levinson, Akbari, and Reilly (2007) and Rosado et al. (2014) for surface temperature measurements on the tiles upper face, precision thermistor was used to continuously track a whole day in the summer season and for a year to evaluate seasonal and annual energy savings in a residence, respectively. The surface temperature analysis by infrared thermography in a comparative way allows to describe the samples temperature differences under the same exposure conditions as was carried out by Synnefa, Santamouris and Apostolakis (2007) and Coelho, Gomes and Dornelles (2017), and also together with infrared thermometer to perform comparative temperature measurements on the coatings upper face as in Synnefa, Santamouris and Livada (2006).

In a simulation by Nie et al. (2024) for a midrise apartment building, cool coatings reduced electricity costs and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, and also promoted indoor comfort conditions improvements for users building, with the most significant results in the warmer climate zones of the United States of America. In downtown Dubai, located in a hot zone, Mohammed et al. (2024) demonstrated the cooling loads reduction due to cool materials application for all building types and heights, regardless of local climate conditions and building materials characteristics.

In Brazil, Ikematsu (2007) and Beleza and Michels (2020) evaluated the thermal performance of reflective paints applied to the substrate of fiber cement tiles, which obtained surface temperature reductions compared to a conventional material. The thermal performance simulation of a cool roof with fiber cement tiles on a single-family single-story residence performed by Barbosa and Marinoski (2024) under low thermal insulation conditions was the best scenario in terms of thermal-energy efficiency for a city with a hot and humid climate like Recife. In the city of Rio de Janeiro, in a simulation, the roof of a similar residence with ceramic and fiber cement tiles with high reflectance, in this order, reduced heat gain by conduction from the roof to the building interior by up to 55% and 60% (Silva; Marinoski; Guths, 2020a, 2020b). Thus, national studies use tiles as substrates for reflective paints or refer to conventional white materials with high solar reflectance as cool to assess thermal performance. The study by Silva and Dornelles (2023) proposed the production of a colored cool concrete tile in laboratory using a technique developed by Levinson et al. (2010) and the evaluation of its mechanical, optical, and thermal properties.

Therefore, cool tiles combine great reflective properties with excellent durability, weathering resistance and aesthetic appeal that only colored materials offer in addition to maintaining their coolest surface as far as traditional tile is concerned.

Theorical background

The Sun is the main source of energy in the Earth-atmosphere system, and the energy process occurs through thermonuclear fusion in its core, in which it transforms hydrogen atoms into helium (Pereira et al., 2017). Thus, radiant energy is emitted by this star in almost all wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum, mainly ultraviolet, visible and near infrared radiation (Yamasoe; Corrêa, 2016).

In the interaction of solar radiation with the Earth’s atmosphere, the physical processes of reflection, direct or diffuse transmission or absorption of radiant energy occur, which causes the attenuation of solar irradiance along its path towards the surface of the Earth. In general, about 5% of the approaching solar radiation is attenuated because of atmospheric absorption (in layers above 40 km), and another 10% to 15% is absorbed by the lower layers of the atmosphere or dispersed back into space (Singh et al., 2020).

The sum of the portions of solar radiation that are transmitted directly (Gdir) and diffuse (Gdif) incident on a horizontal terrestrial surface is called horizontal global irradiance and reaches values of about 1.000 Watts in one square meter at noon. At this time, the Sun is in the position perpendicular to the zenith and crosses the smallest thickness of the atmosphere, considering conditions without cloudiness (Pereira et al., 2017).

Then, the electromagnetic radiation that reaches and interacts with the material of a surface causes the physical processes of emission and absorption that occur in a permanent flow between the substance and the medium in which it is involved. Given this, the amount of energy absorbed varies according to the molecular composition of the matter and the type of incident electromagnetic radiation, which interacts with the electrical charge of the constituent particles of the substance. Therefore, the energy remaining portion, that is, the amount of reflected energy, also depends on the surface matter constitution. As stated, visible spectrum wavelengths (380 to 780 nm) of solar radiation that are reflected and captured by the human eye determine the color visual perception that this object appears to have (Pedrosa, 1982).

Near infrared electromagnetic radiation is non-ionizing radiation, because it cannot expel electrons from the atoms of the material due to its lower frequency (and longer wavelength) (Singh et al., 2020). Therefore, this type of radiation when absorbed only causes the transition of electrons from the ground state to the “excited” through molecular vibration within the energetic level at which they are found (Dwivedi et al., 2020). In this way, the heating is much more evident in the vibrational component, in which the embodied energy is due to absorption in the near infrared spectrum, than is observed in any other type of electromagnetic radiation (Dias; Andrade Neto; Miltão, 2007).

On opaque surfaces, for example, building coating materials, heat-regulating mechanisms are the reflection and absorption of solar radiation. After the interaction, the portion of absorbed radiation heats the material and transfers the thermal energy through the conduction process to the interior environment and the remaining unabsorbed, that is, the portion of the reflected radiation exchanges heat with the adjacent surfaces and the surrounding air that causes the heating (Lim, 2020). Therefore, solar reflectance (ρ) or solar absorptance (α) impacts on surface and air temperature and on heat flow transfer from the outer face of the coating to the interior of the building, which affects its thermal and energy performance.

Thus, this paper presents the assessment of the solar reflectance of cool tiles available in Brazil to identify the effect of color in terms of thermal performance given that in Ikematsu (2007) and Couto (2019), it was observed that one of the color parameters, brightness, has a significant correlation with reflectance in the visible spectrum and solar. Therefore, through color parameters, especially brightness, the reflectance of radiation visible wavelengths is analyzed, considering that the portion absorbed by this surface influences its thermal performance. Therefore, optical and thermal properties characterization in laboratory can provide reliable input data for thermo-energetic simulations of colored cool materials instead of using only conventional white coatings as cool ones. Furthermore, the lack of these data particularly in the national scenario, also supports future research for the development of cool colored materials with near-infrared reflective pigments.

Material and method

In order to evaluate the reflective and thermal performance of the cool roof tiles, they were prepared and cut to measure the parameters of color, solar reflectance, and surface temperature in the field. The color test by instrumental measurement according to E805-22 (ASTM, 2022) and the solar reflectance test using an integrating sphere according to E903-20 (ASTM, 2020a) were chosen from those mentioned in the ANSI/CRRC S100 standard (CRRC, 2021). The surface temperature was measured with the infrared thermometer and a thermographic camera.

Selection of cool roofing materials

A survey was carried out in the national market of civil construction coatings, which indicated in their technical specifications that they present high values of solar reflectance and thermal emittance. These materials have in their nomenclature the designations “thermal” or “reflective” with mention of the reduction of heat exchange with the internal environment and temperature decrease, which brings building energy savings and thermal comfort to the occupants.

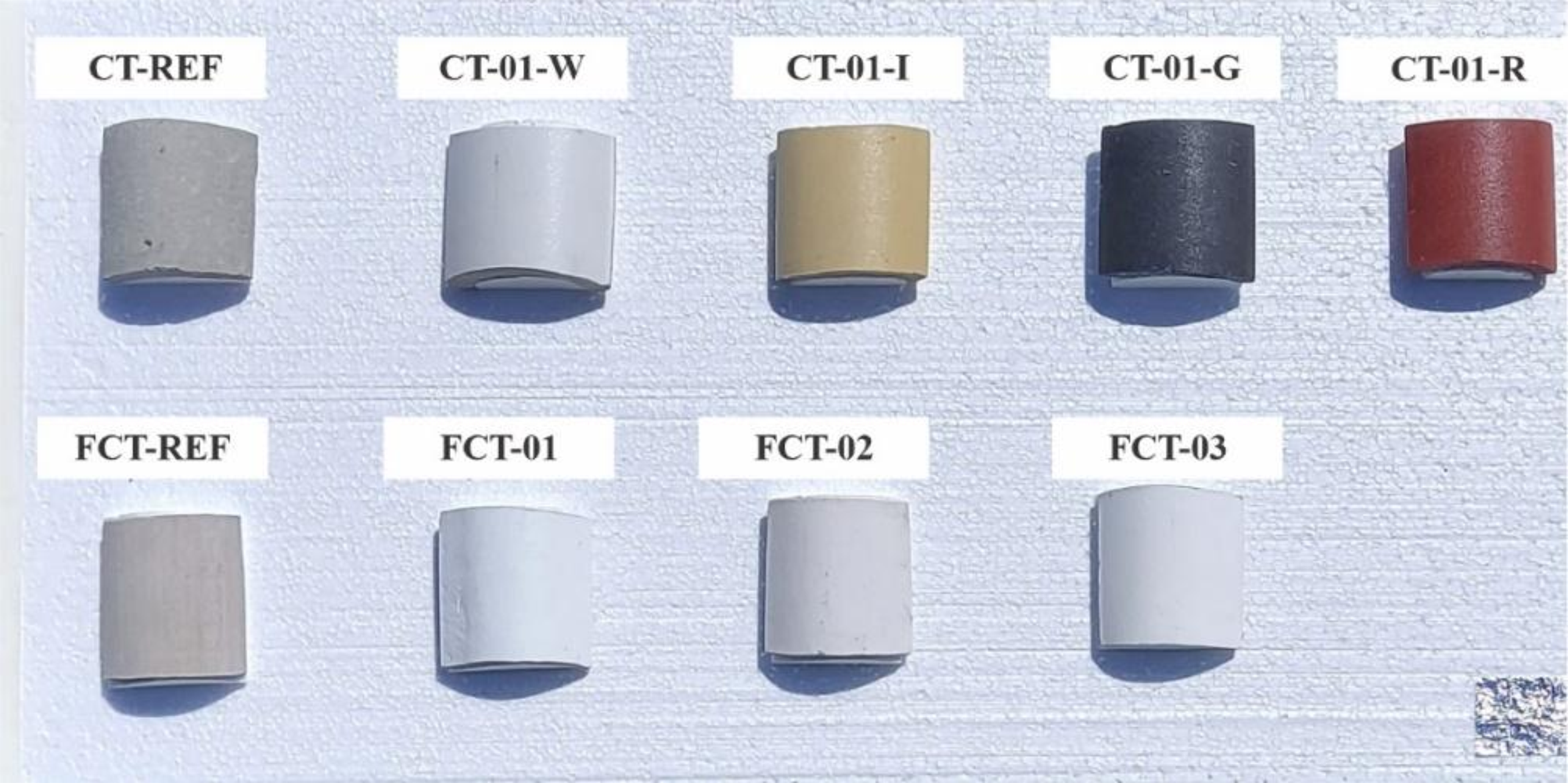

Concrete and fiber cement tiles were selected, and their trade names were omitted and replaced by their nomenclatures such as the terms “Thermo” and “Comfort” and the manufacturers were categorized by letters of the alphabet (Table 1).

Samples of materials that are from the same product line and manufacturer have the same numbering and differ only by the final letter, which corresponds to the initial letter of their coloring. Therefore, the research samples are composed of seven cool tiles and two reference materials with conventional coating, which have the indication - REF at the end of the acronym, a gray concrete (CT-REF) and fiber cement tiles (FCT-REF), without a reflective finish.

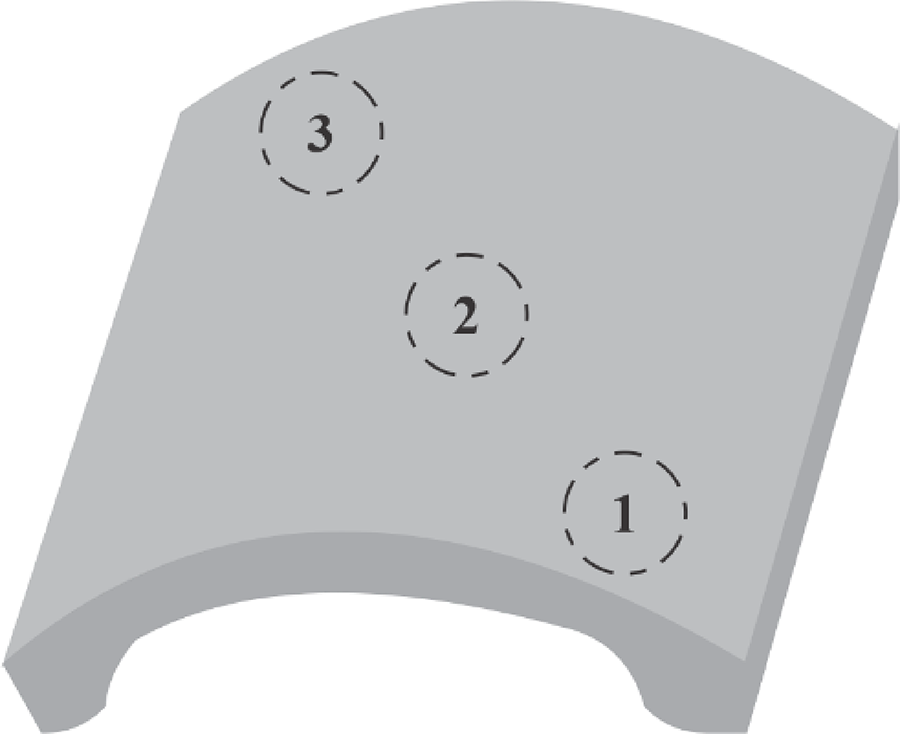

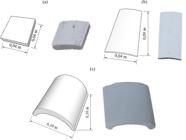

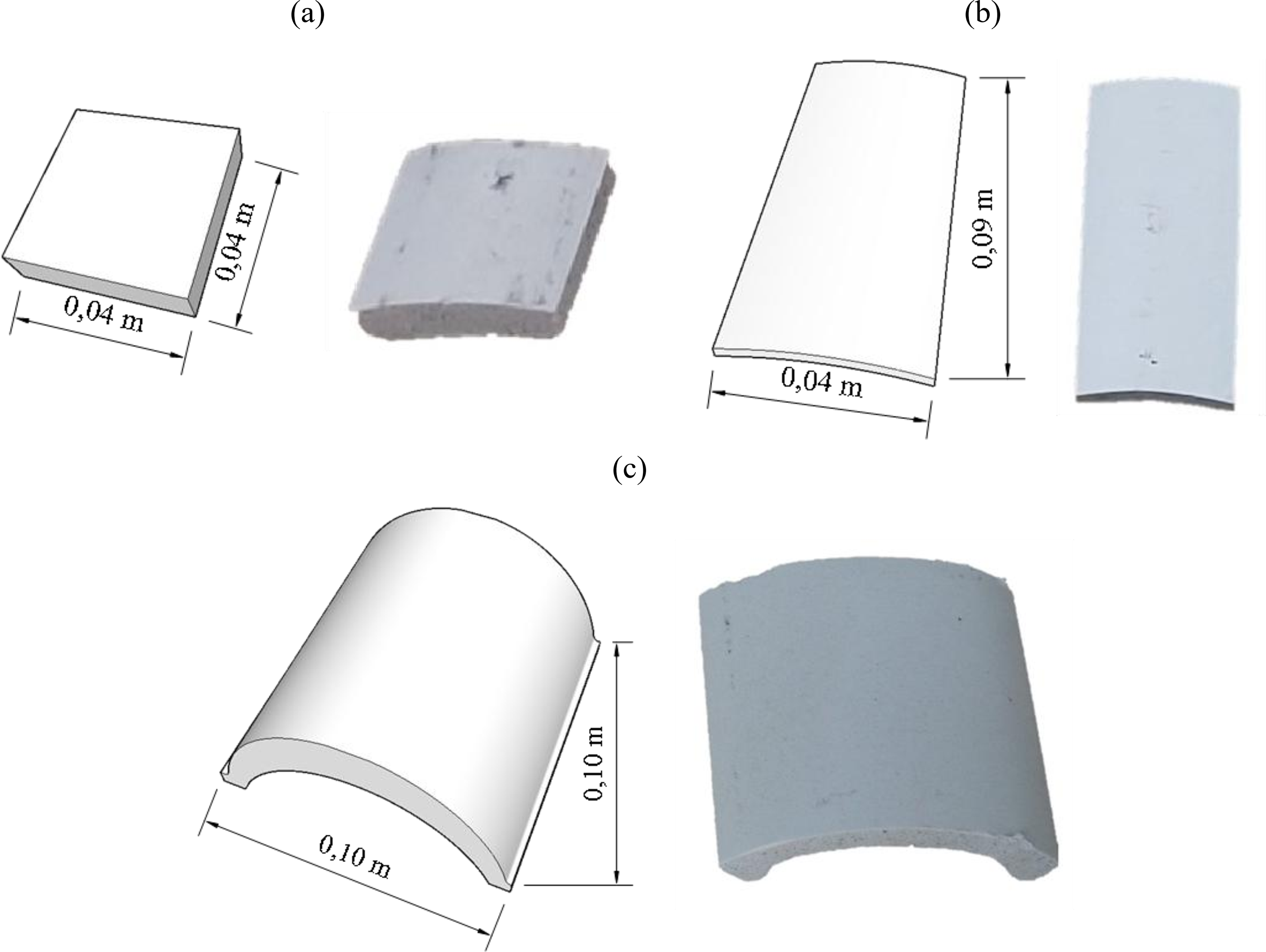

The tiles were cut with a circular saw in the Civil Construction Laboratory of the Institute of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo (IAU/USP). The concrete tiles were cut in the central portion of the ridge, of smaller thickness, from which square pieces were removed in the concrete tiles with a dimension of 4 cm on the side in the convex part of their curved shape as shown in the Figure 1(a) to obtain flatter samples and rectangular pieces with 9 cm for the fiber cement tiles as per Figure 1(b) to suit the integrating sphere of the spectrophotometer for the measurement of solar reflectance. Larger pieces of sharp curvature with a dimension of 10 cm on the side were also cut for the measurements of color and surface temperature parameters according to Figure 1(c).

Sketch with dimensions and cut samples of (a) concrete tile CT-01-W and (b) fiber cement tile FCT-01 for the measurements of solar reflectance and (c) color and surface temperature parameters

Color parameters

The color parameters of the samples were measured by the reflectance colorimeter instrument, Delta Color brand, model Colorium 2, and the technique used colorimetry through the Lab7 software to characterize the surface appearance of the materials. The colorimeter measurements were performed in an internal laboratory environment, without need to control the internal environmental conditions.

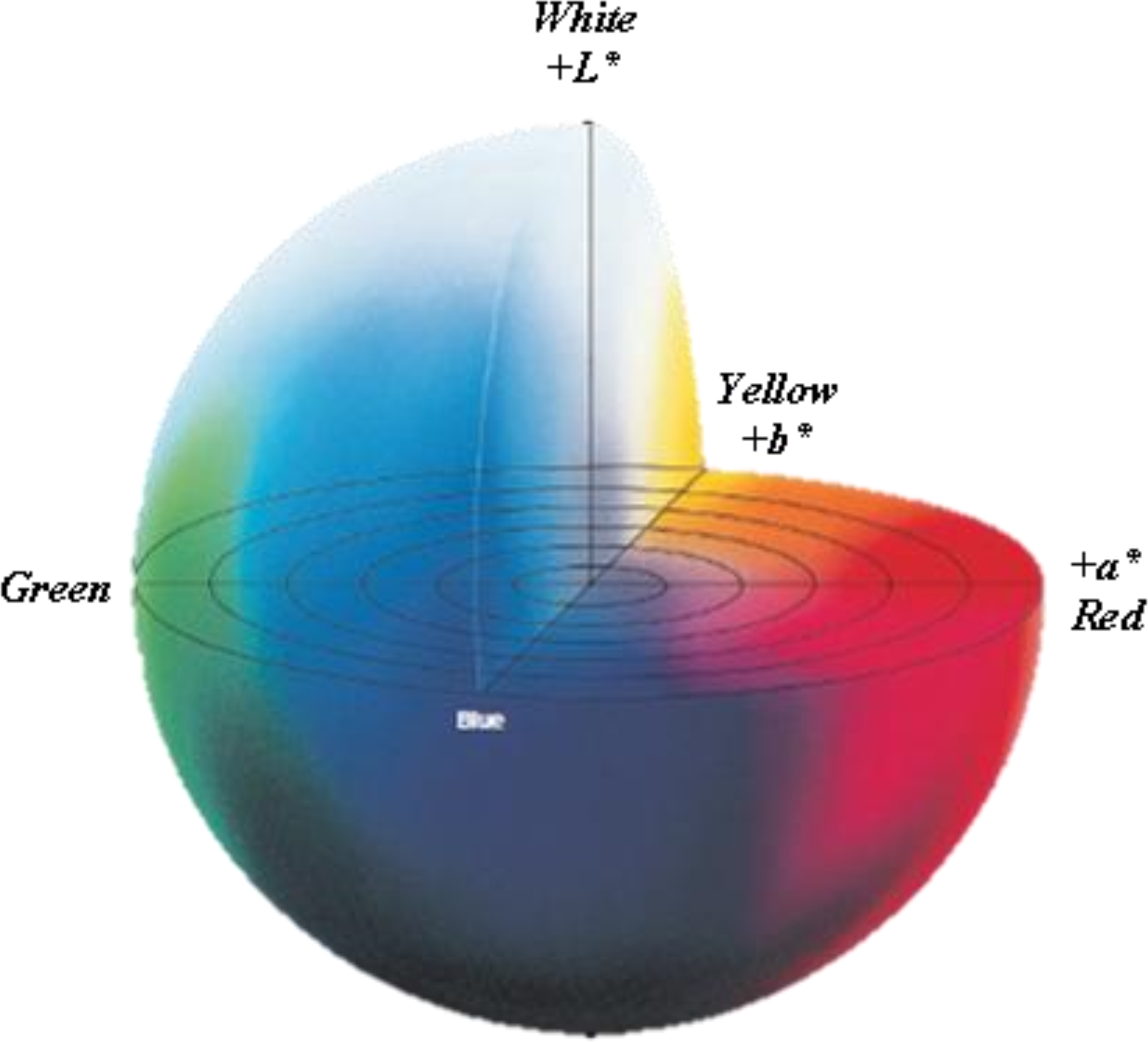

The standards established by the equipment, from the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) references, are the light source with high efficiency LED lamps, whose power distribution is represented by the illuminant D65, the standard 10 ̊ observer and CIE Lab chromatic system, whose geometric coordinates (L*, a* and b*) are related to the three colorimetric characteristics of hue, lightness and saturation, which constitutes an effective color scale in describing visual differences between colors (Delta Color, 2011).

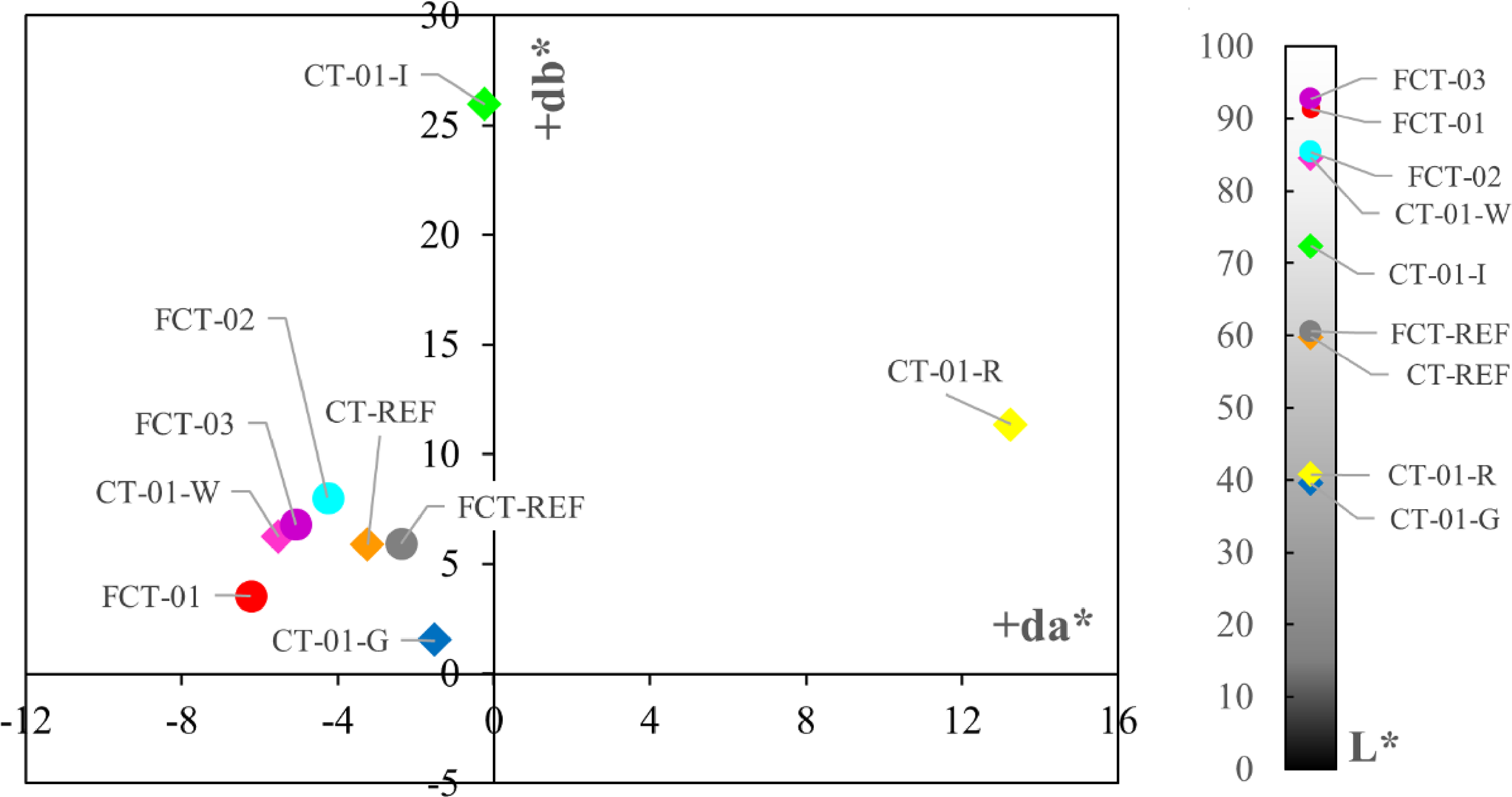

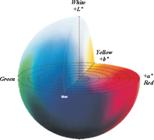

The color was represented in the color circle (Figure 2) by means of numerical codes in the CIE Lab system, whose value referring to the lightness is symbolized by L* on the vertical axis, with the gradient from black (0) to white (100), whose midpoint (50) is the gray color. The hue or chroma, radiated from the central axis, is determined by the intersection of the two axes a* (red-green) and b* (yellow-blue), with their respective positive values in red (+ 120) and yellow (+ 120).

Thus, the L*, a* and b* coordinates were measured in three different regions on the surface of the tiles (Figure 3) and the arithmetic mean value of each color coordinate was calculated for all samples.

Solar reflectance

The measurements were performed with the Perkin Elmer spectrophotometer, Lambda 1050 model, with an integrating sphere of 150 mm in diameter from the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), which provides the spectral curves of solar reflectance following the recommendations of the E903-20 standard (ASTM, 2020a). The samples were inserted into an internal compartment of the spectrophotometer to control the conditions of radiation incidence on the samples.

According to the equipment technical specifications, measurements at ultraviolet and visible wavelength have higher resolution (≤ 0.05 nm) and accuracy (± 0.080 nm) than near infrared region with lower resolution (≤ 0.20 nm) and accuracy (± 0.300 nm) (Marinoski et al., 2013) and the uncertainty of the technique by spectrophotometry is ± 0.02 absolute as stated in E903-20 (ASTM, 2020a). In the calibration of the equipment, a reference sample was used, which in theory has 100% reflectance, which provides a base curve on which the absolute reflectance values of the samples, measured at every 5 nm, were graphically arranged within the region of the electromagnetic spectrum where it has the highest rates of energy from solar radiation according to G173-03 (ASTM, 2020b), dividing it into three sub-regions:

-

the ultraviolet (from 300 to 380 nm);

-

the visible (from 380 to 780 nm); and

-

the near infrared (from 780 to 2500 nm).

However, an adjustment of the reflectances to the standard solar spectrum was performed because of the constant intensity of light emitted by the spectrophotometer lamp during the tests. This energy incidence from the artificial illumination source does not represent the marked variations in the rates of solar radiation incident during the day on surfaces due to atmospheric conditions and latitude, for example. Then, intending to correct the distortions and portraying the real optical behavior of the samples, the standard solar spectrum was used, which considers the global solar hemispheric radiation represented in the G173-03 standard (ASTM, 2020b) as a weighting function to adjust the absolute values measured by the spectrophotometer with the values of the global solar irradiance for each wavelength according to the procedure adopted in Dornelles (2008).

Surface temperature

The tile samples were exposed at 09 hours and 30 minutes in the morning, on April 26, 2022, in an open area near the Environmental Comfort Laboratory, facing the geographic North in clear sky conditions with maximum exposure to solar radiation in the city of São Carlos, SP (22°S, 47.5°W, 819 m). For this purpose, they were positioned on an experimental bench with a Styrofoam base, thermally insulated from each other, which avoided heat exchanges by convection and radiation at the bottom of the experiment (Figure 4). The equipment chosen for surface temperature measurements was the infrared thermometer, Testo Brasil brand, with 1-point laser sight, model 830-T1 and the thermal camera, Flir brand, model E5-XT.

Climate monitoring

From the exposure of the tiles, the climatic variables of relative humidity and air temperature were obtained by the HMP 35c probe, Vaisala model, and the global solar radiation was measured by the pyranometer model SP Lite, manufacturer Kipp and Zonen. This equipment was connected to the data acquisition system with data logger CR10X, Campbell Scientific Brasil brand, which records and stores the measured data per minute in the PC400 software, which calculates the average values of the climatic variables every 30 minutes of measurement.

This system was installed next to the tiles natural aging rack of Araújo (2022), on the campus of the University of São Paulo in the city of São Carlos (SP), near the site of the surface temperature measurement experiment, to characterize the external climatic conditions.

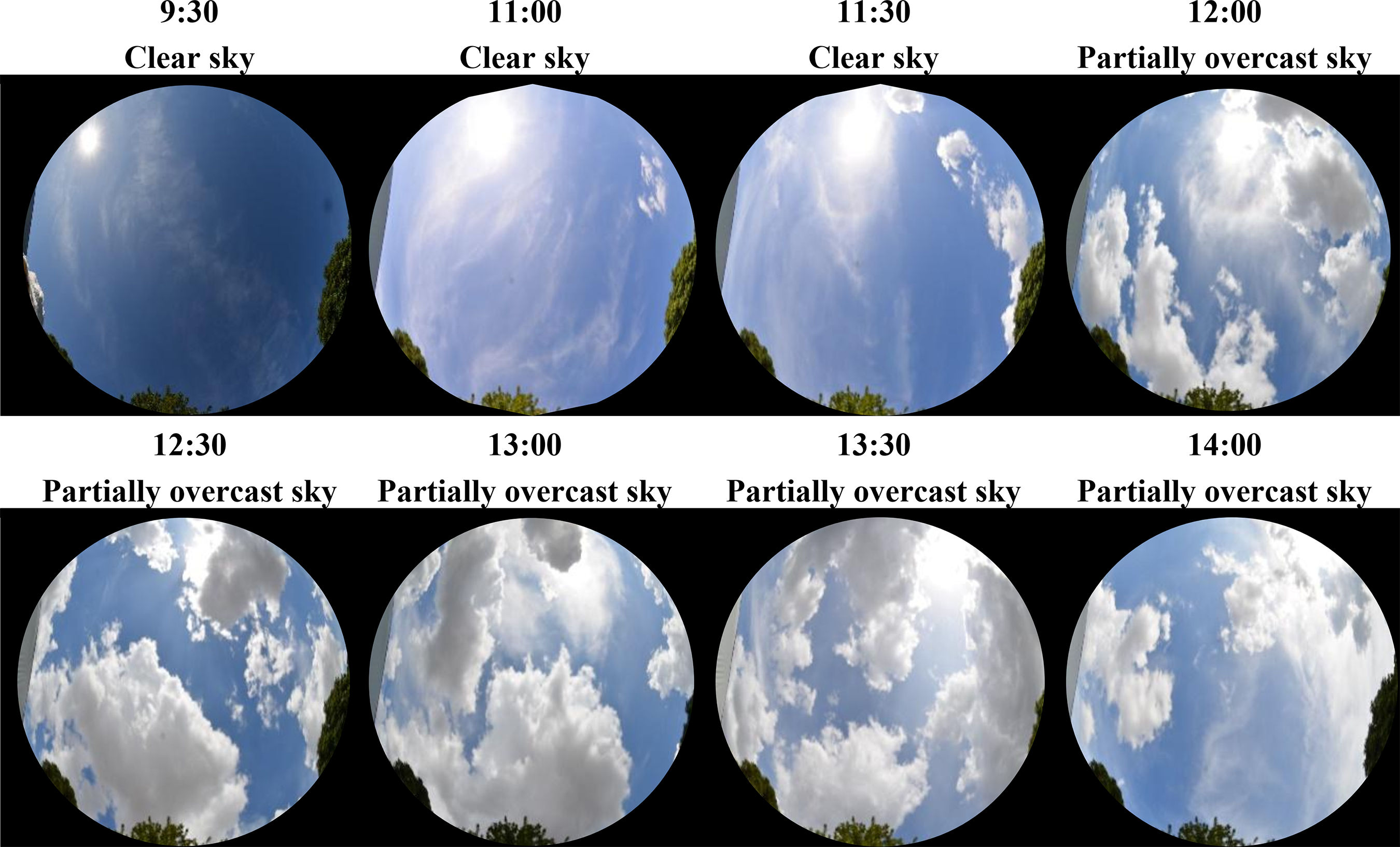

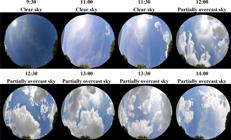

Records were also made of the celestial dome with a fisheye lens model AF DX Fisheye-NIKKOR 10.5 mm f/2.8g ED coupled to the NIKON® digital camera model D5100, which was positioned on a tripod 1.30 m from the ground at a distance of 2.00 m from the experimental bench. Therefore, hemispherical sky photos were used to record sky conditions at the time of measurements and their identification as clear, covered or partially covered sky according to NBR 15215-2 (ABNT, 2022a), which deals with calculation procedures for the spatial distribution of natural light.

Infrared thermometer

Measurements with the infrared thermometer Testo Brasil, model 830-T1, began at 11 am, at 12-minute intervals, and were performed until 2 pm, in a measurement cycle of 3 consecutive hours, totaling 16 measurements during the exposure time that was selected because of the high incidence of solar radiation at this time of the day. The input parameters were set at 0.90 for thermal emissivity and 20 °C for air temperature. The accuracy of the thermometer is ± 1.5 °C for surface temperatures ranging from +0.1 °C to +400 °C and the infrared resolution is 0.1 °C (Testo do Brasil, 2020).

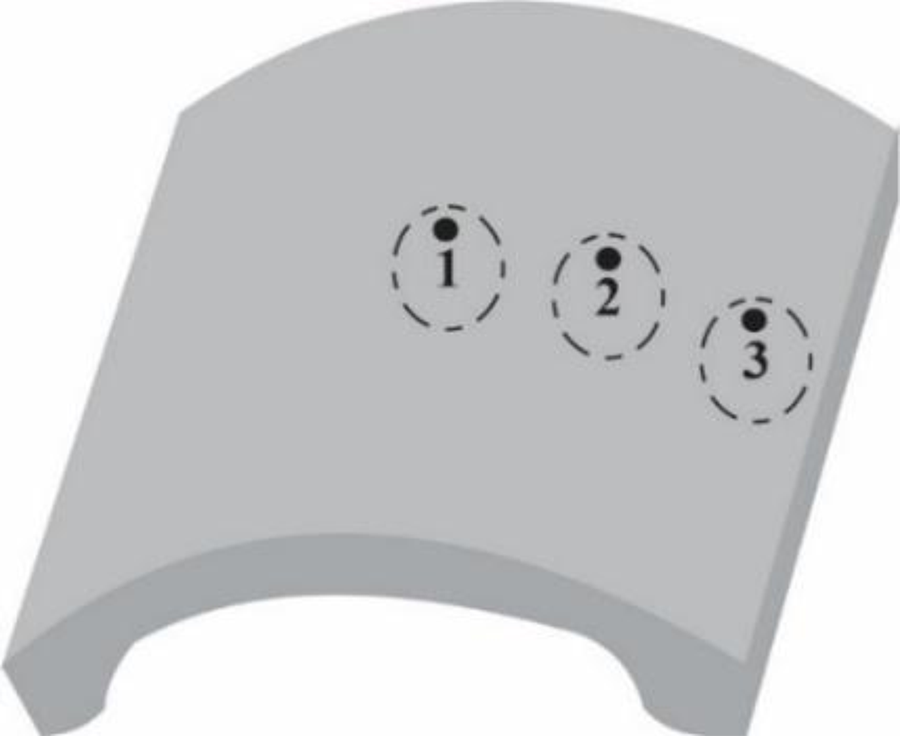

The surface temperature measurement on the cool tiles and reference tiles were performed at 03 different points on the surface because of the difference in the incidence of solar radiation due to the wavy aspect of the tiles. The thermometer was positioned about 15 cm from the sample that has a laser beam for the gaze. Then, because of its standard optics (10:1) the measurement point marking on the sample is circumscribed in a circle about 2 cm in diameter (Figure 5). Thus, the final value of the surface temperature of each tile was obtained through the arithmetic mean of the three measured values (Equation 1).

Where in the following applies:

Tsup is the average surface temperature (°C);

T1 is the surface temperature at point 01 (°C);

T2 is the surface temperature at point 02 (°C); and

T3 is the surface temperature at point 03 (°C).

Thermographic camera

After measuring the surface temperatures by the infrared thermometer, thermographic images of the Styrofoam where the tile samples were positioned were recorded. Thermography recording with the thermal camera was performed with the operator positioned on a chair holding the equipment in the position perpendicular to the Styrofoam, at a distance of 1.50 m from the laser point to the upper face of the Styrofoam, in order to allow the visualization of all tile samples.

The time of the records was set every 30 minutes, also starting at 11 am, which totaled 07 thermographic images, so as not to coincide with the measurement times of the infrared thermometer. The initial input parameters, i.e., prior to measurements, were set at 20 ˚C for air temperature and reflected apparent temperature, a parameter used to compensate for reflected radiation on the object, and at 0.95 for thermal emissivity. The infrared image quality is 160 x 120 pixels, the thermal sensitivity less than 0.10 °C and the accuracy of ± 2 °C given that the air temperature variation from 10 °C to 35 °C (Teledyne Flir, 2015).

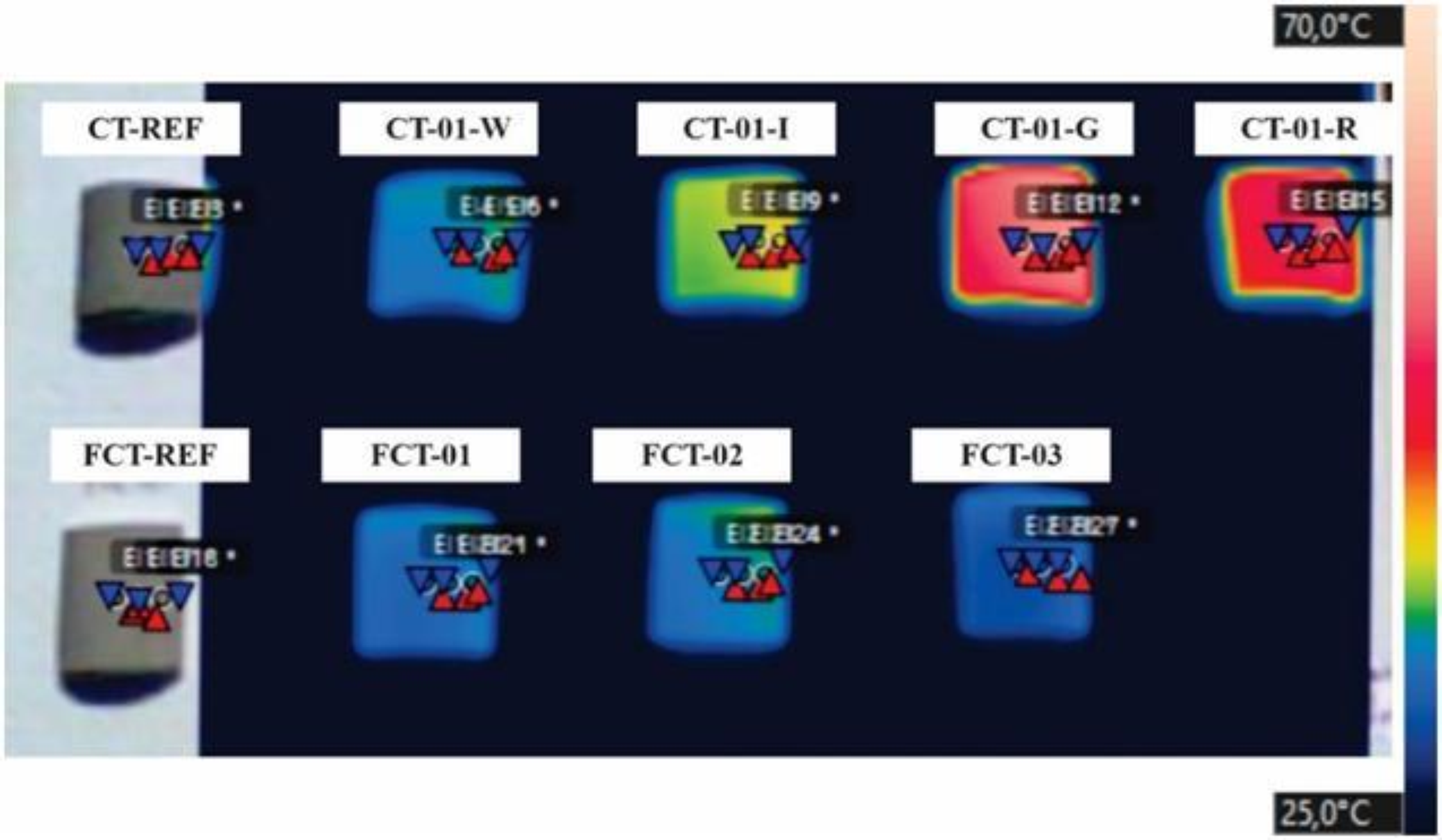

Thermographic images were treated with FLIR Tools® software to measure the surface temperature of the samples. In the infrared photo, one millimeter contains the information of a frame. For this, they were overwritten in three different positions of the tile circles containing twenty-one frames as the measurement interval of the research, as was performed with the infrared thermometer to obtain the average, maximum and minimum temperature values (Figure 6).

Thermographic image treatment of tiles at 11:30 am in FLIR Tools® software in “Picture-in-picture” mode

Thus, all input parameters were modified in the software with the air temperature data obtained in the storage system in Araújo (2022) according to the hourly record of each thermal image as well as the thermal emissivity values of each sample that were measured by the portable emissometer, model AE1, from Devices & Services. To determine the reflected apparent temperature, the research used the simplified method of Marinoski et al. (2010) when fixing an aluminized tape to the lower right portion of the Styrofoam plate next to the tile samples. However, by the initial settings of the thermographic camera, the average temperature value on the tape, an object of low thermal emissivity, was very low. In this case, the suggested device was adopted to simply adjust the reflected temperature by matching its value to that of the ambient air temperature.

Statistical analysis

The data were previously submitted to the Shapiro-Wilk (normality of errors) and Cochran’s T (homogeneity of variance) tests, which were satisfactory at 5% significance. Statistical analysis was supplemented with the Scott-Knott cluster test at 5% statistical significance. This test allows grouping the means of the surface temperature values of the evaluated materials considered statistically equal for the two thermographic measurement techniques. The groupings were presented by means of boxplot graphs made in the Excel program.

Pearson correlation analysis was performed to assess the degree of dependence between variables. Regression analysis was performed between color lightness (independent variable) with visible and solar reflectance. Linear regression analysis was also performed between visible and near infrared reflectance as independent variables in relation to the maximum surface temperature measured by the infrared thermometer and thermographic camera. The Scott-Knott test, Pearson correlation and linear regression were performed with the scripts available in the free software RBio (Bhering, 2017).

Results and discussion

Color parameters

Figure 7 shows the graphic arrangement of the tile colors and the chromatic parameters of the CIELab system, measured by the colorimeter, are presented for cool tiles and reference tiles (Table 2). Values presented in Table 2 with green and blue colors refer to high values, color red to low values, and yellow to the values that are being compared.

The cool tiles of white concrete (CT-01-W), gray (CT-01-G), and ivory (CT-01-I), in terms of hue, are in the quadrant of the green (- a*) and yellow (+ b*) axes, with the highest value of b* (+ 25.97) in the ivory tile, which shows the highest presence of yellow in its composition. Then, the red tile (CT-01-R) with a large amount of yellow (b* = + 11.36) but is on the positive axis + a* (red), being the only one, among the tiles, with the hot color temperature (Figure 7).

The gray reference tile (CT-REF) has a*b* hue values even closer to those of the white cool tile (CT-01-W) than the gray cool tile (CT-01-G), which is very close to the intersection of the a*b* axes and also has a lower L* lightness value (Figure 7). Despite this, the difference in lightness L* in relation to the red tile (CT-01-R) is negligible (ΔL* = ± 1.23) since they are practically superimposed according to Figure 7 while the white concrete tile (CT-01-W) is the most luminous, that is, with more brightness followed by the ivory (CT-01-I) and gray reference tiles (CT-REF) taking into account the concrete ones.

The reference fiber cement tile (FCT-REF) has lower lightness L* in color and the cool white FCT-02, among those of fiber cement, is the only one that has lightness L* with a value less than 90 (85.42), so it is the tile that has less white in its composition, followed by the FCT-01 and FCT-03 tiles, in this order, and therefore, are the most luminous, but with a negligible difference (ΔL* = ± 1.43) between them (Table 2). Regarding hue, the highest amount of yellow (+ b*) is found in the fiber cement tiles FCT-02, FCT-03 and FCT-01, in this order, there are lower amounts of green (- a*) in their hue compositions (Figure 7).

Solar reflectance

The measured spectral reflectance values and fitted to the standard solar spectrum in the three sub-regions:

-

ultraviolet (300 to 380 nm);

-

visible (380 to 780 nm); and

-

near infrared (780 to 2000 nm) and solar reflectance are presented in Table 3 for the cool tiles.

Reflectance measurement for reference concrete (CT-REF) and fiber cement (FCT-REF) tiles was not performed because of their dimensions and curved shapes that did not fit the integrating sphere. The results are presented to three decimal places as indicated in the manual of the classification program of cool roof products (CRRC, 2022) of the Cool Roof Rating Council (CRRC). Values presented in Table 3 with green and blue colors refer to high values, red to low values, and yellow to the values that are being compared.

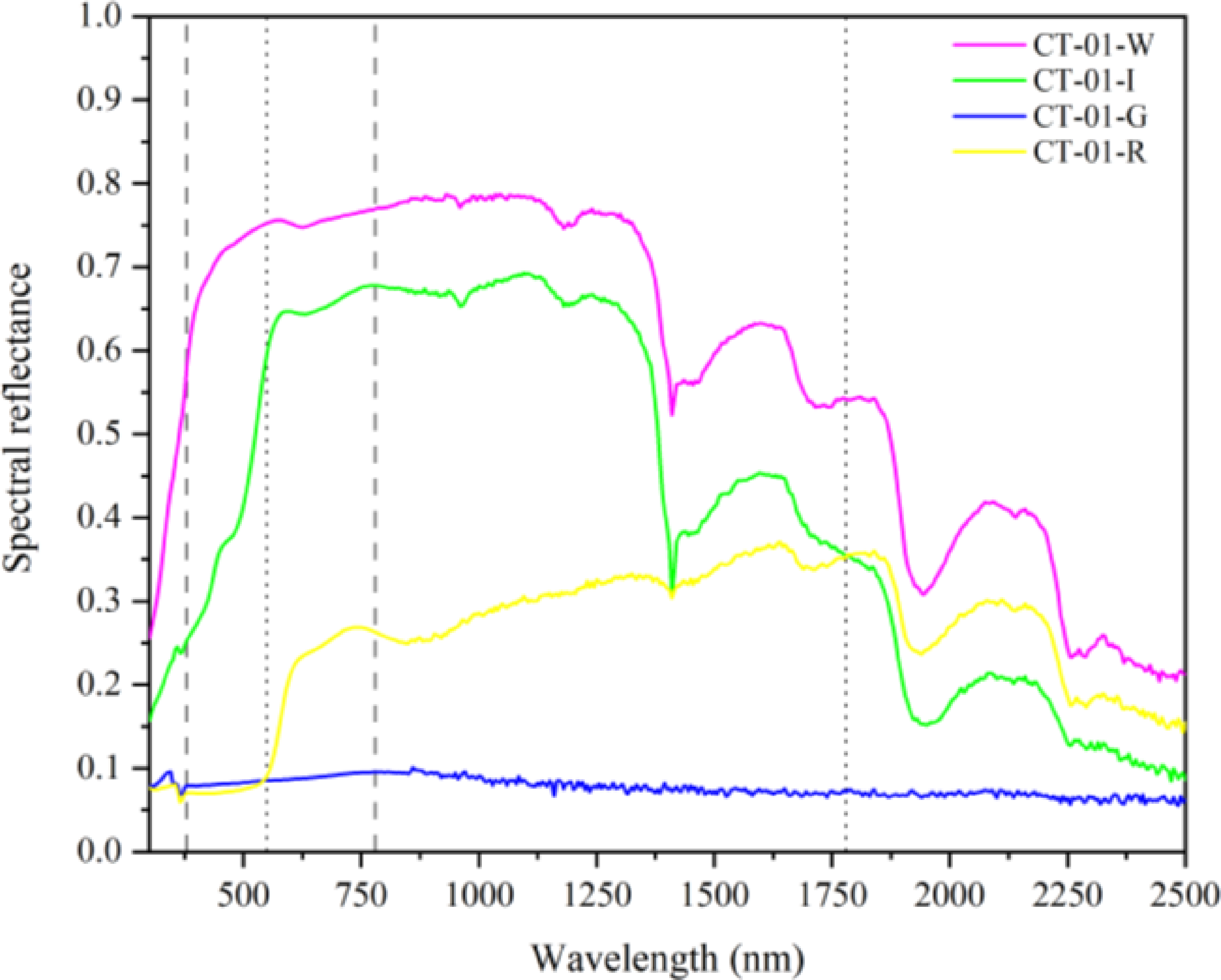

White (CT-01-W) and ivory (CT-01-I) concrete tiles have the highest reflectance values in all spectral regions while the darkest, gray (CT-01-G) and red (CT-01-R) tiles have the worst reflective performances in ultraviolet, visible spectra, as observed in dark hues, and in near infrared region (Table 3).

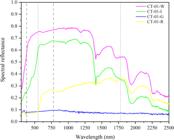

The spectral reflectance curves obtained in the spectrophotometric measurements detail the reflective behavior of the samples at each wavelength. As a consequence, the curves of the white (CT-01-W) and ivory (CT-01-I) tiles as shown in Figure 8 show similar reflectance patterns. The curve of the gray tile (CT-01-G) is constant and always below 10% reflectance while the red (CT-01-R) shows a gradual increase from 550 nm in the visible region and exceeds ivory at 1780 nm, which improves its reflective performance in the near infrared. From this wavelength, the curves of the white, ivory and red tiles show the same reflection behavior (Figure 8).

White (CT-01-W) and ivory (CT-01-I) cool tiles have higher values of solar reflectance and infrared spectrum than those found in conventional colored concrete tiles evaluated in Araújo (2022). The cool red tile (CT-01-R) did not reach solar reflectance value (ρsolar = 0.218) close to those found in the cool red tiles (ρsolar = 0.33 to 0.43) of Levinson et al. (2010), just as the cool gray tile (CT-01-G) has a lower value in the near infrared (ρNIR = 0.084) compared to the black cool coating (ρNIR = 0.35) of Levinson et al. (2007) applied directly to a concrete tile.

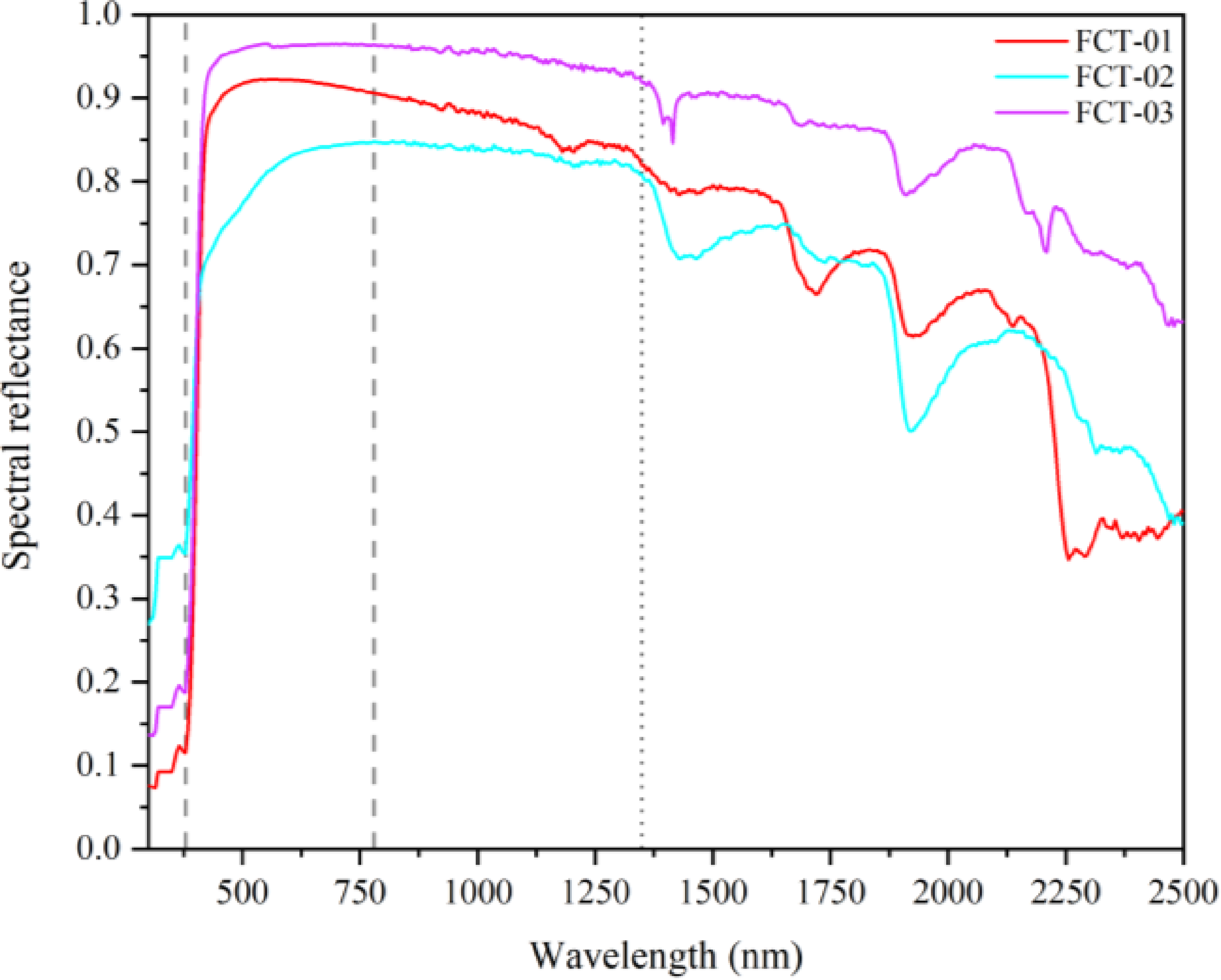

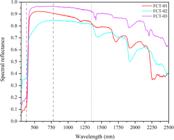

The FCT-03 fiber cement tile has the best reflective performance in all spectral regions, greater than 0.90 in visible and near infrared spectrum, so it reached a high value of solar reflectance (ρsolar = 0.915), and then 0.843 for the FCT-01 tile and 0.786 for the FCT-02 tile (Table 3).

All curves according to Figure 9 have high reflectance levels in the visible region (especially FCT-03 tile), because they are white, and remain high up to the wavelength of 1350 nm when their curves decay to the end of the near infrared region as observed in the fiber cement reflective tiles evaluated by Couto (2019).

Concrete tiles have a resin in their surface layer, which gives them a smooth and homogeneous finish, so they are less rough and porous than fiber cement tiles. The cool white concrete tile (CT-01-W) has a lower reflectance value in visible, near infrared and solar than all white fiber cement tiles (Table 3). Therefore, the interreflections caused by diffuse solar radiation to other points of this rough surface of fiber cement tiles did not have a considerable effect on heat absorption since only the first interreflection significantly affects the solar absorptance according to the study by Roriz (2007).

Surface temperature

Climate monitoring

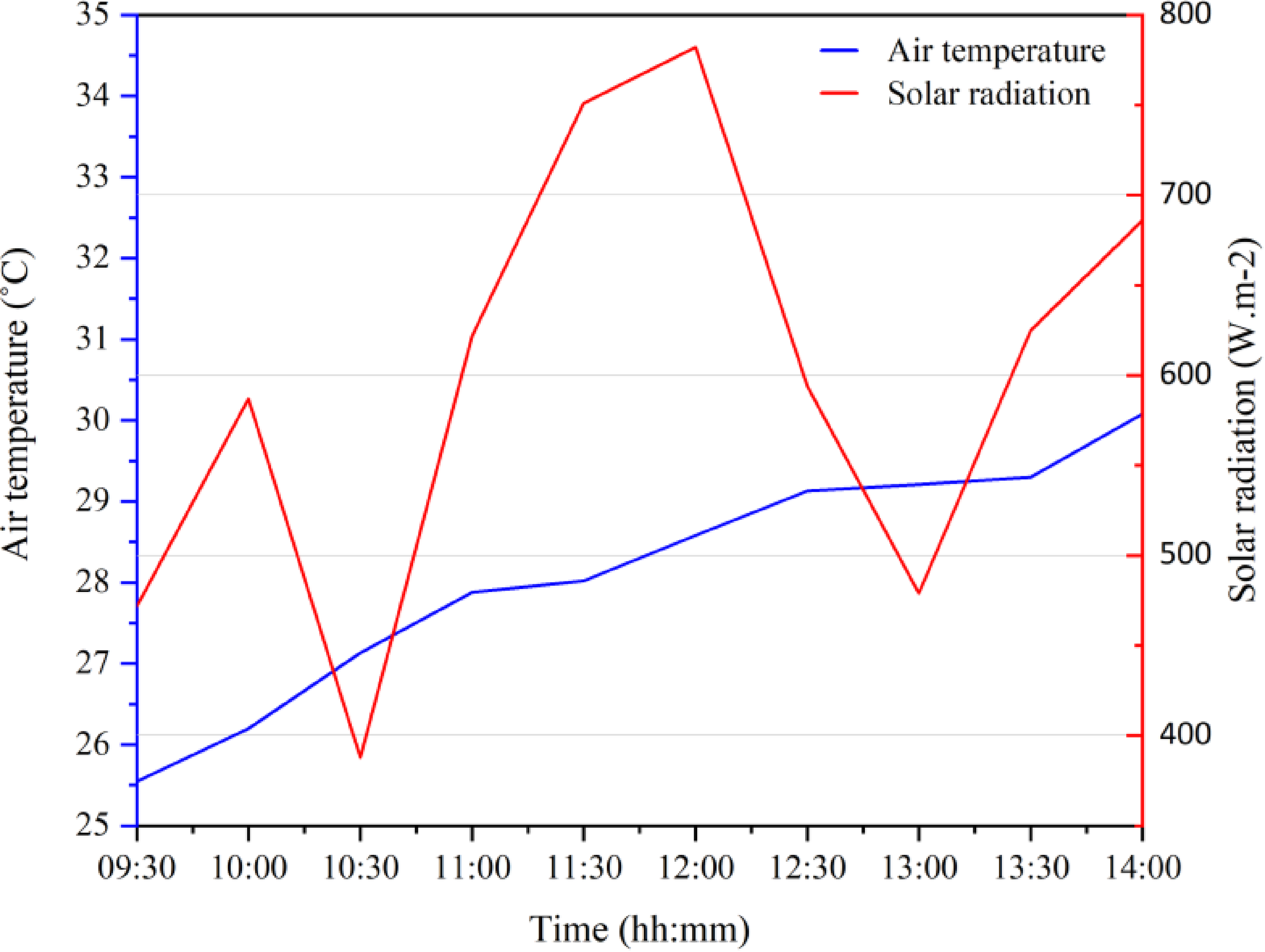

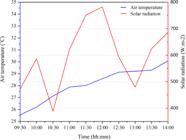

The mean values of the climatic variables during the entire exposure period of the field samples that were recorded in the data storage system are represented (Table 4). Values presented in Table 4 with blue color refers to low values and red to high values. The variation of dry bulb air temperature (°C) values and solar irradiance (W.m-2) are depicted in Figure 10 over exposure time.

During the monitored period, there are moments of alternation with increases and decreases in solar radiation because of the appearance of clouds with the lowest solar intensity (388 W.m-2) at 10:30 am while the air temperature gradually rises throughout the period according to Figure 10 while the relative humidity of the air is gradually reduced (Table 4).

At 9:30 am at the beginning of the experiment and in the period from 10:30 am to 12 pm, at which time the solar irradiance (782 W.m-2) is maximum, when the surface temperature measurements unfolded, the prevailing sky condition is clear. However, there is a change to the partially covered sky due to the protrusion of the clouds until the end of the experiment according to the hemispherical images (Figure 11), but the air temperature value only increases and reaches its apex (30.08 °C) at 14 pm.

The records of the celestial vault with a fisheye lens during the period of sun exposure of the tiles

Infrared thermometer and thermographic camera

Infrared thermography was used to investigate the temperature distribution of the samples and to describe the differences in their thermal performance. Differences in thermal behavior between samples of the same type of material or color were observed in coatings by Synnefa, Santamouris and Livada (2006) because of spectral reflectance.

Some difficulties reported in the use of the infrared thermometer were the handling of the equipment at the same distance for all tiles and the accuracy in the laser sight at the predetermined points in the samples. A disadvantage was the time lapse that occurs from the measurement of the first sample with the thermometer to the last one positioned in the Styrofoam, which differs from the thermal image that captured all the tiles at the same instant. Others were the impossibility of changing the input data, such as thermal emissivity and air temperature a posteriori as performed in the thermal camera software, which also allows versatility in the extraction of temperature data with the delimitation of the frames. Despite this, the groups of mean surface temperature values identified by the Scott-Knott test were coincident for the two equipment.

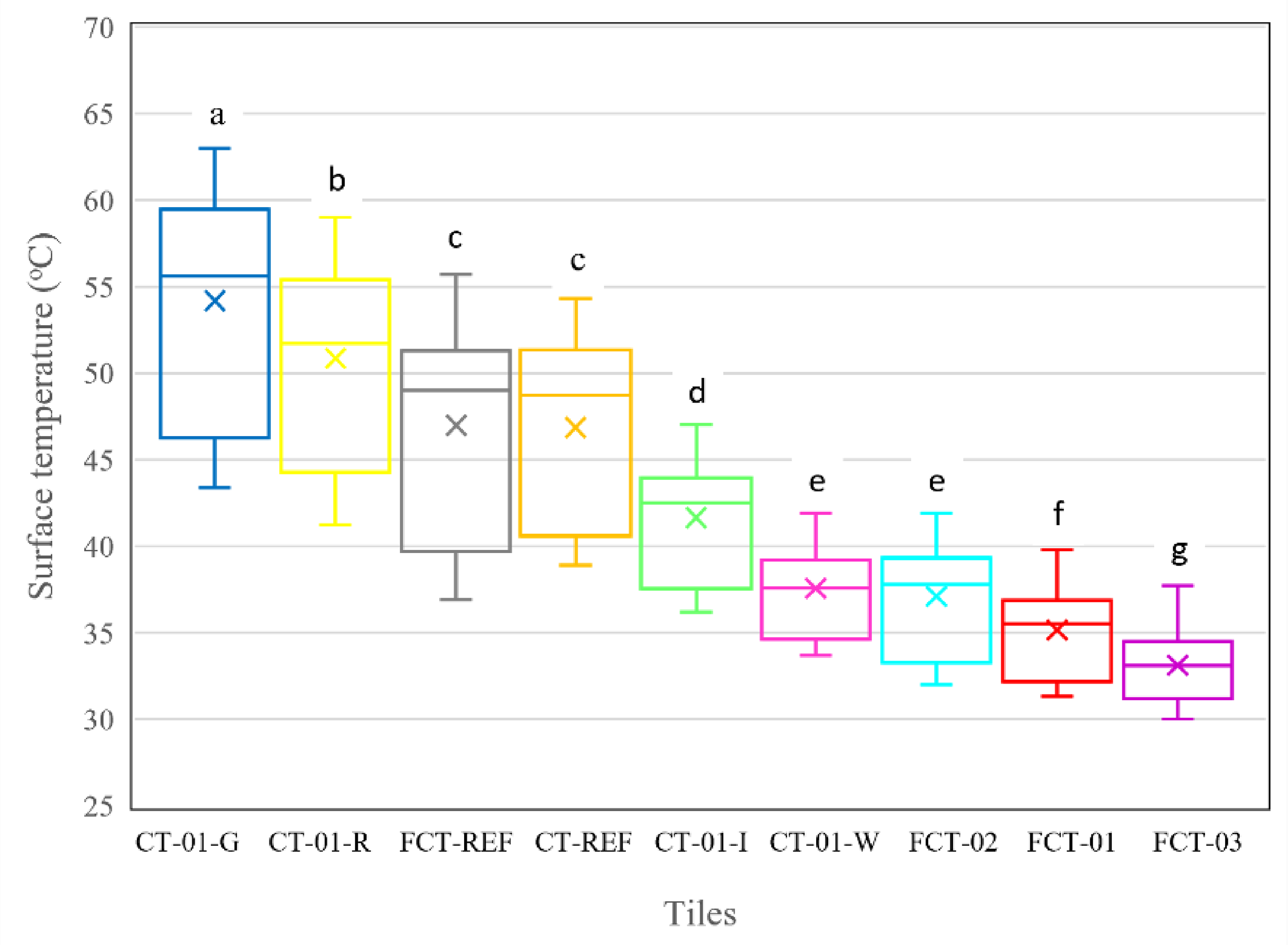

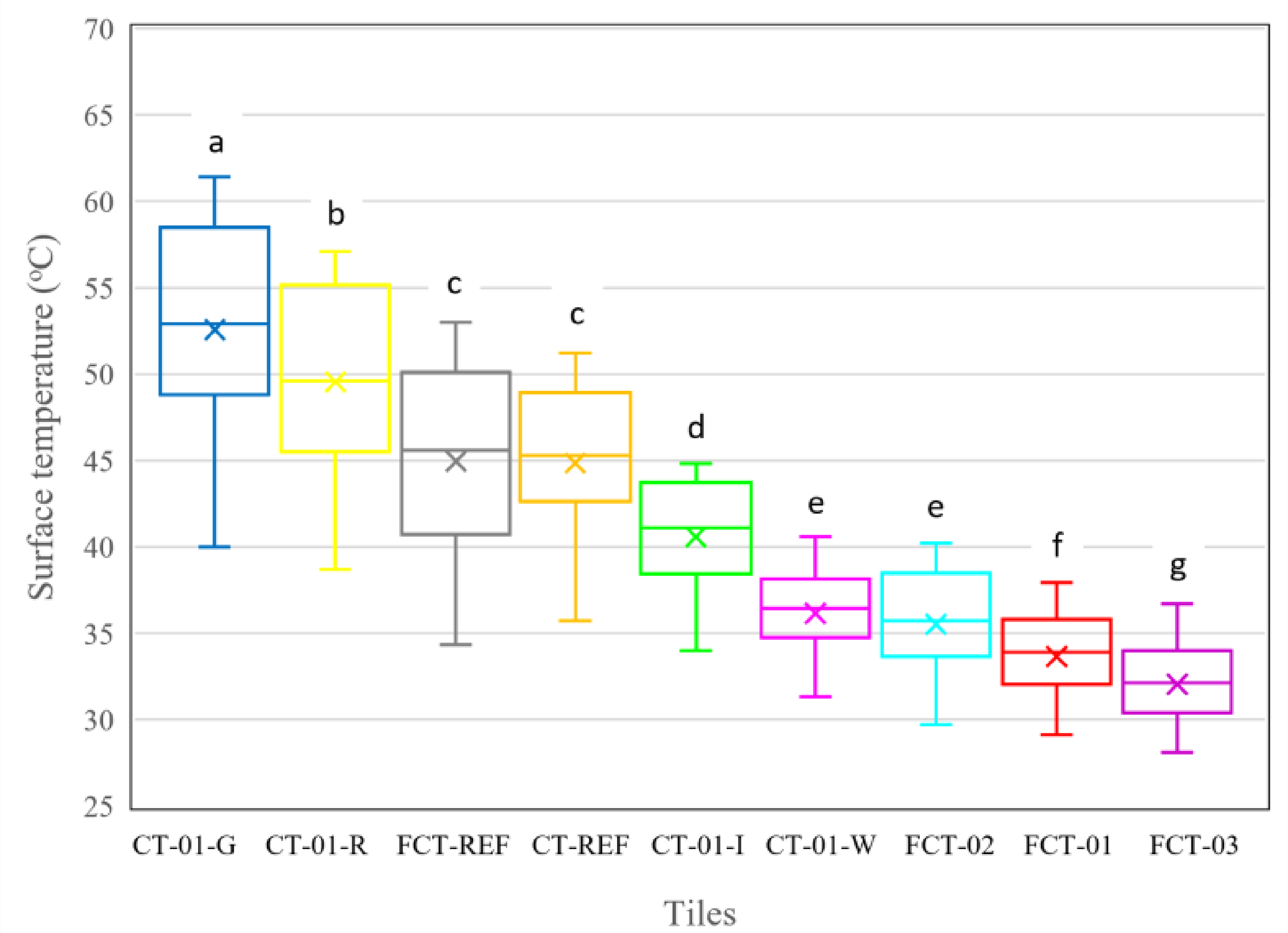

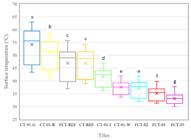

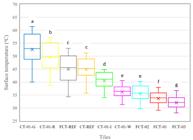

The temperature data of the average values extracted from the frames of thermographic camera (Figure 12) and the values of the thermometer (Figure 13) were represented in the form of boxplot diagram graphs. It is notorious that the temperature distributions are divided into two groups, which indicates that the temperature of the colored tiles (groups “a” to “d”) was much higher than in the white tiles (groups “e” to “g”).

Boxplots of the temperature distribution of the tiles, in descending order, measured by the thermal camera

Boxplots of the temperature distribution of the tiles, in descending order, measured by the infrared thermometer

The concrete tiles in gray (CT-01-G) and red (CT-01-R) colors, despite the reflective coating, are the tiles that heated up the most during the measurement period. These tiles with the lowest lightness values L* of color and spectral and solar reflectance have the highest maximum and minimum values recorded.

The graphical representation of the temperature of the reference tiles FCT-REF and CT-REF by the boxplots are similar especially between the graphs represented by the thermal camera (Figure 12) despite the difference in the composition of the two materials. The distribution of the data set is also correlated since the FCT-REF fiber cement tile and CT-REF concrete tile have values close to median (corresponding to the horizontal line inside the rectangle) and mean (represented by the symbol “x” inside the rectangle) in both graphs. Although the solar reflectance measurement was not performed on these reference tiles, which are gray, they have almost the same lightness value L* of color and a negligible difference was also found between their thermal amplitudes (ΔTmax - Tmin) of only ± 0.1 °C in the comparison between the two-measuring equipment.

The white (CT-01-W) and ivory (CT-01-I) concrete tiles, despite present higher solar reflectance values than the cool concrete tile (ρsolar = 51%) from Rosado et al. (2014), have smaller reductions in their upper faces temperatures, respectively, by 12.4 ºC and 7.3 ºC in relation to the conventional concrete tile from Rosado et al. (2014) when compared to the asphalt shingle (13.8 ºC) on a typical summer day.

The FCT-02 white fiber cement tile has a slightly higher color L* lightness value and also near infrared (ρNIR) and solar (ρsolar) reflectance than the CT-01-W white concrete tile. Despite this, these tiles reach maximum temperature values equal to or very close to despite the lowest minimum values for the fiber cement tile. Thus, the fiber cement tile has a greater interquartile range and thermal amplitude because of the composition of its material, which has a lower specific heat (c = 0.84 kJ/kg.K) in a comparasion with concrete (c = 1.00 kJ/kg.K). This thermal property measures the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of a component by 1 degree (ABNT, 2022b). Therefore, less heat is needed, that is, less thermal energy from the Sun to increase the temperature of the fiber cement tile in relation to that of concrete and because of this it presents greater variation. Couto and Dornelles (2021) observed that fiber cement tiles also have a higher thermal amplitude because of their specific heat compared to ceramic tiles with the same solar absorptance values.

The FCT-01 white fiber cement tile has solar reflectance (ρsolar = 0.843) close to 85% followed by FCT-03 white tile with values greater than 90% in solar reflectance (ρsolar = 0.915), in the near infrared spectrum (ρNIR = 0.928) and visible (ρVIS = 0.934), and so, they have the lowest maximum and minimum surface temperatures recorded.

The FCT-03 fiber cement tile has the lowest thermal amplitudes in the two-measuring equipment despite its fiber cement composition due to the high reflectance of its surface, especially in the near infrared, which absorbs less thermal energy, which results in little heat accumulation over the exposure period. The FCT-03 tile also has symmetric data distribution, that is, the mean and median are coincident within the boxplot in both graphs.

The red ceramic tile commonly used in Italy showed a surface temperature 7 °C and 4 °C warmer, respectively, when compared to the terracotta tiles manufactured with the addition of colored mineral pigments by Pisello et al. (2013), which have greater visual similarity to the conventional tile. The cool concrete tiles by Levinson, Akbari and Riley (2007), which vary from terracotta to black, showed a 15% to 37% increase, in this order, in solar reflectance compared to conventional tiles of similar color, and a reduction in the surface’s peak temperature from 4.6 °C to 13.8 °C, respectively. In this sense, this study did not evaluate conventional tiles of the same color as the cool ones for comparison purposes, which is therefore a limitation to evaluate the thermal performance improvement.

In general, the boxplots have the highest thermal amplitude (ΔTmax -Tmin) for the infrared thermometer data, although the thermal camera records the highest maximum and minimum values and also the largest interquartile ranges, a region in which most of the data is concentrated around the mean and median. Thus, the greater the thermal amplitude and the interquartile range, the greater the variability of the temperature data of the tiles, that is, the materials gain and lose heat more easily. Therefore, smaller ranges indicate greater stability at the material temperature.

Statistical analysis

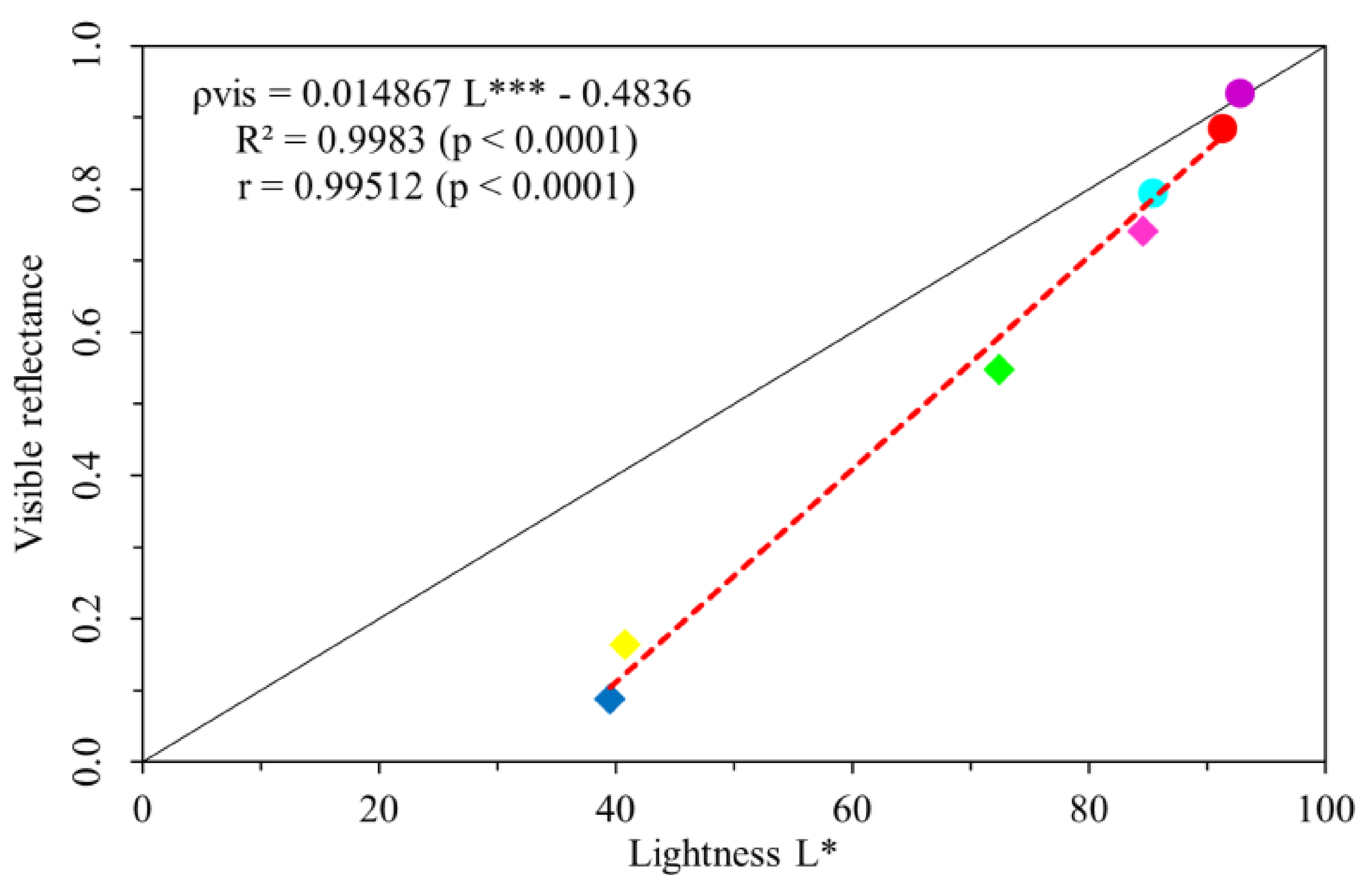

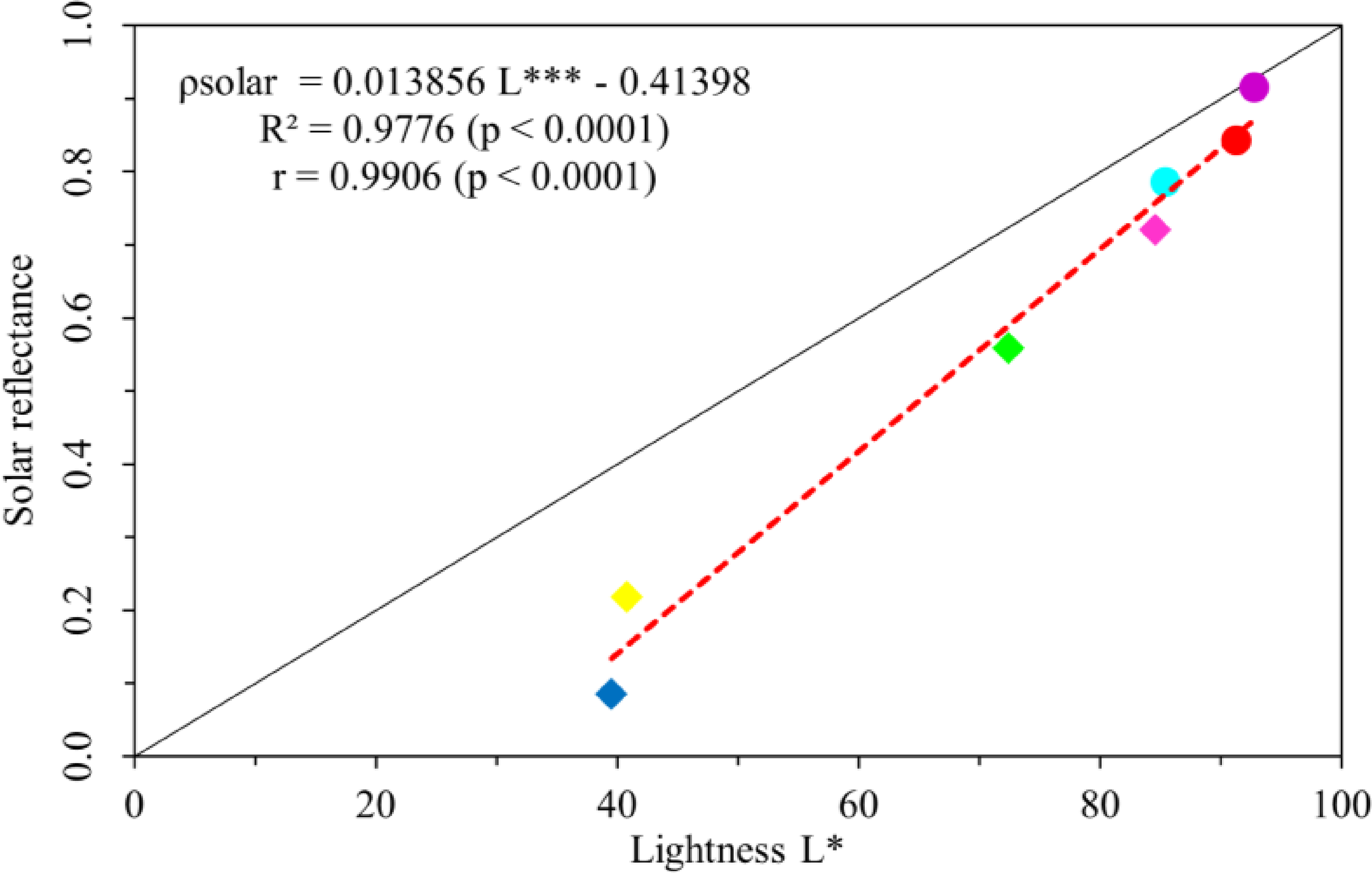

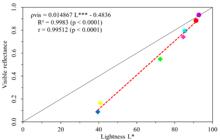

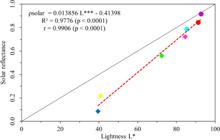

In the evaluation of the dependence and relationship between the different parameters, Pearson’s correlation and linear regression analysis were performed between the lightness L* (color parameter that indicates how much white there is in the color) with the reflectance values in the visible region (Figure 14) and solar (Figure 15).

The correlation (r) and determination coefficients (R2) have p values much lower than 0.05 (p < 0.001), which gives them high statistical significance. There is a high relationship between the values of visible reflectance (ρVIS) and solar (ρsolar) with color lightness because of the positive correlation with high correlation coefficients (r) equal to 0.99512 (p < 0.001) and 0.9906 (p < 0.001). That is, as the lightness value of the materials increases, there is a corresponding increase in the visible and solar reflectance values. The 10% increases in the lightness of the tiles by the linear regression equations increases the visible reflectance by 0.14867 (Figure 14) and the solar by 0.13856 (Figure 15), in this order, for L* values equal to or greater than 40. Therefore, there is a significant linear relationship between lightness with coefficients of determination R2 of 0.9983 (p < 0.001) and 0.9776 (p < 0.001), for visible spectrum and solar reflectance, respectively. So, the visible reflectance represented by the lightness, i.e., the amount of black or white on the color scale, has an impact on solar reflectance as demonstrated.

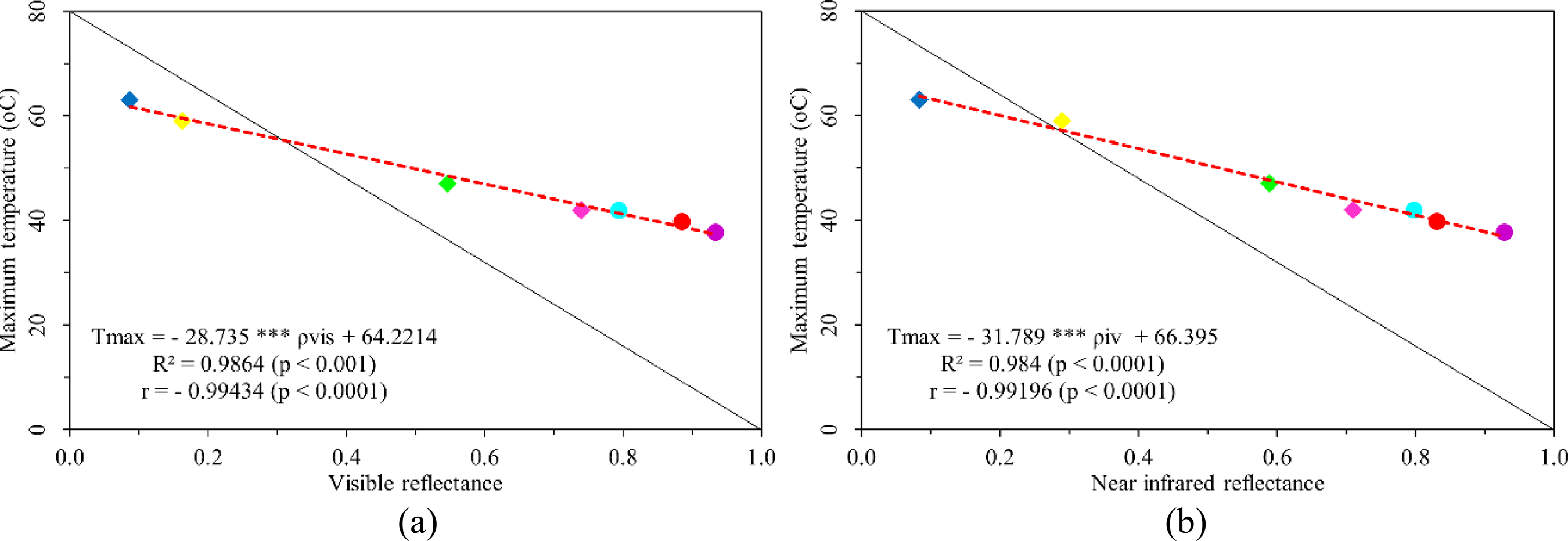

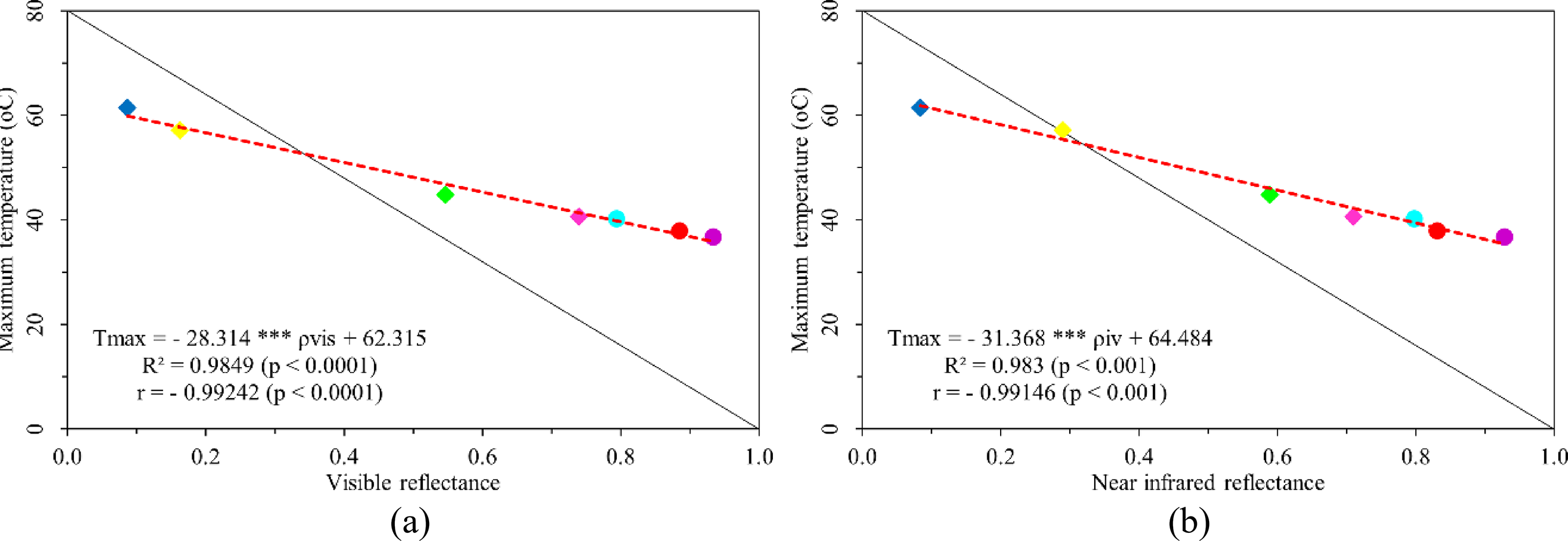

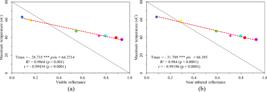

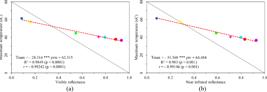

Then, to analyze the influence of visible reflectance on surface temperature, Pearson’s correlation and linear regression analysis were performed between reflectance in the visible region (ρVIS) and in the near infrared (ρNIR) with the maximum temperature recorded in the infrared camera (Figure 16) and in the thermometer (Figure 17).

(a) Correlation between visible reflectance and maximum temperature (camera) and (b) correlation between infrared reflectance and maximum temperature (camera)

(a) Correlation between visible reflectance and maximum temperature (thermometer) and (b) correlation between infrared reflectance and maximum temperature (thermometer)

The correlation (r) and determination coefficients (R2) have p values much lower than 0.05 (p < 0.001), which gives them high statistical significance. Correlation coefficients (r) greater than – 0.99 indicate the high correlation with negative sign between the maximum temperature in the thermal camera (Figure 16) and in the thermometer (Figure 17) with the reflectances in the visible and near infrared spectrum. That is, as the visible and near infrared reflectance increases, the maximum surface temperature value decreases. For each relationship, the coefficient of determination R2 has a value close to 1.00 (greater than 0.98), which indicates that the regression fitted well (linear trend) and in fact there is a linear regression between the surface temperature with the reflectance in the visible and near infrared spectrum. In linear regression equations, the temperature reduction of the tiles by approximately 2.85 °C and 3.15 °C occurs with the 10% increase in visible and near infrared reflectance, respectively. Therefore, the best predictive model of linear regression between maximum temperature and reflectance is the near infrared, which was more sensitive to temperature variations indicated by the higher value of the angular coefficient of the equations.

Conclusions

Cool concrete tiles did not present reflective performance close to that observed in concrete tiles developed internationally by Levinson et al. (2010), except for tiles in white and ivory colors because of the higher reflectance in the visible spectrum due to the lighter coloration. The cool white fiber cement tiles showed better reflective performance in the visible region and also in the near infrared in relation to the cool concrete tile of the same color despite its smooth surface finish.

Colored tiles are the hottest during the period of sun exposure with the highest temperatures on the surface of gray and red concrete tiles, despite the reflective coating, so they have worse thermal performances than a conventional concrete tile. Even in white concrete and fiber cement tiles that have solar reflectance values close, a temperature difference was verified because of the composition of their material. The fiber cement ones have greater variation in view of the fact that they gain and lose heat more easily because of their specific heat and the whites that have warmed less, that is, they have remained cooler because of the better reflective performance.

So, white cool tiles heat up less predominantly because of their coloration and because of this they achieved better thermal performance, which was not found in this study for dark color tiles, which depend on the addition of more reflective pigments to the near infrared to obtain better reflective and thermal performances.

Acknowledgements

The present experimental research was funded by the São Paulo State Research Support Foundation (FAPESP) that granted a master’s degree scholarship (Process n° 2019/20050-9). The opinions expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect FAPESP views. Special thank to Professor Deivis Marinoski, from the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC) for his contribution to tiles’ solar reflectance measurement.

References

- AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR TESTING AND MATERIALS. E805-22: standard practice for identification of instrumental methods of color or color-difference measurement of materials. West Conshohocken, 2022.

- AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR TESTING AND MATERIALS. E903-20: standard test method for solar absorptance, reflectance and transmittance of materials using integrating spheres. West Conshohocken, 2020a.

- AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR TESTING AND MATERIALS. G173-03: standard tables for reference solar spectral irradiances: direct normal and hemispherical on 37o tilted surface. West Conshohocken, 2020b.

- ARAÚJO, A. C. H. Absortância solar e o envelhecimento natural de telhas expostas ao tempo. São Carlos, 2022. 208 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Arquitetura e Urbanismo) - Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo, São Carlos, 2022.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NBR 15215-2: iluminação natural: procedimentos de cálculo para a estimativa da disponibilidade de luz natural e para a distribuição espacial da luz natural. Rio de Janeiro, 2022a.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NBR 15220-2: desempenho térmico: componentes e elementos construtivos das edificações: resistência e transmitância térmica: métodos de cálculo. Rio de Janeiro, 2022b.

- BARBOSA, M. M; MARINOSKI, D. L. Comportamento termoenergético de edificação unifamiliar com uso de tetos frios: estudo de caso na cidade de Recife/PE. In: ENCONTRO NACIONAL DE TECNOLOGIA DO AMBIENTE CONSTRUÍDO, 20., Maceió, 2024. Anais [...] Maceió: ANTAC, 2024.

- BELEZA, A. A. S.; MICHELS, C. Análise da refletância e do desempenho térmico de tinta reflexiva aplicada em cobertura de telhas de fibrocimento. In: ENCONTRO NACIONAL DE TECNOLOGIA DO AMBIENTE CONSTRUÍDO, 18., Porto Alegre, 2020. Anais [...] Porto Alegre: ANTAC, 2020.

- BHERING, L. L. RBio: a tool for biometric and statistical analysis using The R platform. Crop Brewing and Applied Biotechnology, Viçosa, v. 17, p. 187-190, jun. 2017.

- COELHO, T. C. C.; GOMES, C. E. M.; DORNELLES, K. A. Desempenho térmico e absortância solar de telhas de fibrocimento sem amianto submetidas a diferentes processos de envelhecimento natural. Ambiente Construído, Porto Alegre, v. 17, n. 1, p. 147-161, jan./mar. 2017.

- COOL ROOF RATING COUNCIL. CRRC-1 Roof product rating program manual Portland: CRRC, 2022.

- COOL ROOF RATING COUNCIL. Standard test methods for determining radiative properties of materials Portland: ANSI/CRRC, 2021.

- COUTO, L. S. B. Alta II: uma alternativa aos métodos de medição de refletância solar para telhas cerâmicas e de fibrocimento. São Carlos, 2019. 163 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Arquitetura e Urbanismo) - Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo, São Carlos, 2019.

- COUTO, L.; DORNELLES, K. Análise da temperatura superficial de telhas cerâmicas e de fibrocimento com diferentes absortâncias. In: ENCONTRO NACIONAL DE CONFORTO E AMBIENTE CONSTRUÍDO, 16.; ENCONTRO LATINO-AMERICANO DE CONFORTO E AMBIENTE CONSTRUÍDO, 12., Palmas, 2021. Anais [...] Porto Alegre: ANTAC, 2021.

-

DELTA COLOR. Colorium: colorímetros. 2011. Available: https://www.deltacolorbrasil.com/colorimetro_colorium.html Access: 11 maio 2024.

» https://www.deltacolorbrasil.com/colorimetro_colorium.html - DIAS, A. A. C.; ANDRADE NETO, A. V.; MILTÃO, M. S. R. A atmosfera terrestre: composição e estrutura. Caderno de Física da UEFS, Feira de Santana, v. 5, n. 1/2, p. 21-40, 2007.

- DORNELLES, K. A. Absortância solar de superfícies opacas: métodos de determinação e base de dados para tintas látex acrílica e PVA. Campinas, 2008. 160 f. Tese (Doutorado em Engenharia Civil) - Faculdade de Engenharia Civil, Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2008.

- DWIVEDI, C. et al. Infrared radiation and materials interaction: active, passive, transparent and opaque coatings. In: DALAPATI, G. K.; SHARMA, M. (ed.). Energy saving coating materials Amsterdã: Elsevier, 2020.

- FERRARI, C. et al. Design of a cool color glaze for solar reflective tile application. Ceramics International, Amsterdã, v. 41, n. 9, p. 11106–11116, 2015.

- FERRARI, C.; MUSCIO, A.; SILIGARDI, C. Development of a solar-reflective ceramic tile ready for industrialization. Procedia Engineering, Amsterdã, v. 169, p. 400–407, 2016.

- FROTA, A. B.; SCHIFFER, S. R. Manual de conforto térmico 5. ed. São Paulo: Studio Nobel, 2001.

- IKEMATSU, P. Estudo da refletância e sua influência no comportamento térmico de tintas refletivas e convencionais de cores correspondentes São Paulo, 2007. 117 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Engenharia de Construção Civil e Urbana) - Escola Politécnica - Departamento de Engenharia de Construção Civil, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2007.

- KONICA MINOLTA. Precise color communication: color control from perception to instrumentation. Osaka: Konica Minolta Sensing Inc, 2007.

- LEVINSON, R. et al. A novel technique for the production of cool colored concrete tile and asphalt shingle roofing products. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, Amsterdã, v. 94, n. 6, p. 946–954, 2010.

- LEVINSON, R. et al Methods of creating solar-reflective nonwhite surfaces and their application to residential roofing materials. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, Amsterdã, v. 91, n. 4, p. 304–314, 2007.

- LEVINSON, R.; AKBARI, H.; REILLY, J. C. Cooler tile-roofed buildings with near-infrared-reflective non- white coatings. Building and Environment, Amsterdã, v. 42, n. 7, p. 2591–2605, 2007.

- LIM, Y.-F. Novel materials and concepts for regulating infra-red radiation: radiative cooling and cool paint. In: DALAPATI, G. K.; SHARMA, M. (ed.). Energy Saving Coating Materials Amsterdã: Elsevier, 2020.

- MARINOSKI, D. L. et al. Análise comparativa de valores de refletância solar de superfícies opacas utilizando diferentes equipamentos de medição em laboratório. In: ENCONTRO NACIONAL DE CONFORTO E AMBIENTE CONSTRUÍDO, 12.; ENCONTRO LATINO-AMERICANO DE CONFORTO E AMBIENTE CONSTRUÍDO, 8., Brasília, 2013. Anais [...] Porto Alegre: ANTAC, 2013.

- MARINOSKI, D. L. et al. Utilização de imagens em infravermelho para análise térmica de componentes construtivos. In: ENCONTRO NACIONAL DE TECNOLOGIA DO AMBIENTE CONSTRUÍDO, 13., Canela, 2010. Anais [...] Porto Alegre: ANTAC, 2010.

- MOHAMMED, A. et al. On the energy impact of cool roofs in Dubai. Solar Energy, Amsterdã, v. 272, p. 01-15, 2024.

- NIE, X. et al Energy and cost savings of cool coatings for multifamily buildings in U.S. climate zones. Advances in Applied Energy, Amsterdã, v. 13, p. 01-15, 2024.

- PEDROSA, I. Da cor à cor inexistente 3. ed. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 1982..

- PEREIRA, E. B. et al. Conceitos básicos. In: PEREIRA, E. B. et al. Atlas Brasileiro de energia solar 2. ed. São José dos Campos: Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovações e Comunicações - Instituto Nacional de Pesquisa Espacial, 2017.

- PISELLO, A. L. et al Development of clay tile coatings for steep-sloped cool roofs. Energies, Basiléia, v. 6, n. 8, p. 3637–3653, 2013.

- RORIZ, V. F. Refrigeração evaporativa por aspersão em telhas de fibrocimento: estudo teórico e experimental. São Carlos, 2007. 171f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Construção Civil) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Construção Civil, Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, 2007.

- ROSADO, P. J. et al. Measured temperature reductions and energy savings from a cool tile roof on a central California home. Energy and Buildings, Amsterdã, v. 80, p. 57-71, 2014.

- SHIRAKAWA, M. Consórcio brasileiro de superfícies frias e desempenho termoenergético de edificações com coberturas de alta refletância solar. [Entrevista concedida a] Diana Csillag. Centro de Inovação em Construção Sustentável (CICS), São Paulo, p. 1-5, novembro, 2020.

- SILVA, M. P.; MARINOSKI, D.; GUTHS, S. Avaliação de telhados cerâmicos de alta refletância solar através de simulação termoenergética e análise econômica em uma residência unifamiliar. In: ENCONTRO NACIONAL DE TECNOLOGIA DO AMBIENTE CONSTRUÍDO, 18., Porto Alegre, 2020. Anais [...] Porto Alegre: ANTAC, 2020a.

- SILVA, M. P.; MARINOSKI, D.; GUTHS, S. Simulação termoenergética e análise econômica do uso de telhados de fibrocimento de alta refletância solar em uma residência unifamiliar. In: ENCONTRO NACIONAL DE TECNOLOGIA DO AMBIENTE CONSTRUÍDO, 18., Porto Alegre, 2020. Anais [...] Porto Alegre: ANTAC, 2020b.

- SILVA, W. S.; DORNELLES, K. A. Desenvolvimento e avaliação do desempenhotermoenergético de uma telha de concreto fria para edificações residenciais: estudo piloto em São Carlos-SP. In: ENCONTRO NACIONAL DE CONFORTO NO AMBIENTECONSTRUÍDO, 17., São Paulo, 2023. Anais [...] Porto Alegre: ANTAC, 2023.

- SINGH, V. et al Solar radiation and light materials interaction. In: DALAPATI, G. K.; SHARMA, M. (ed.). Energy Saving Coating Materials Amsterdã: Elsevier, 2020.

- SYNNEFA, A.; SANTAMOURIS, M. White or light colored cool roofing materials. In: KOLOKOTSA, D.; SANTAMOURIS, M.; AKBARI, H. (org.). Advances in the development of cool materials for the built environment Sharjah: Bentham Science Publishers, 2012.

- SYNNEFA, A.; SANTAMOURIS, M.; APOSTOLAKIS, K. On the development, optical properties and thermal performance of cool colored coatings for the urban environment. Solar Energy, Amsterdã, v. 81, n. 4, p. 488 497, 2007.

- SYNNEFA, A.; SANTAMOURIS, M.; LIVADA, I. A study of the thermal performance of reflective coatings for the urban environment. Solar Energy, Amsterdã, v. 80, n. 8, p. 968–981, 2006.

-

TELEDYNE FLIR Tools+. Versão 6.4.18039.1003 [S.l.]: Teledyne FLIR, 2015. Available: https://support.flir.com/SwDownload/app/RssSWDownload.aspx?ID=1247 Access: 16 set. 2024.

» https://support.flir.com/SwDownload/app/RssSWDownload.aspx?ID=1247 - TELEDYNE FLIR. Manual do usuário FLIR Ex series Wilsonville: TELEDYNE FLIR LLC, 2015.

- TESTO DO BRASIL. Ficha de dados Testo 830: instrumento de medição de temperatura por infravermelho. Campinas: Testo SE & Co. KGaA, 2020.

- YAMASOE, M. A.; CORRÊA, M. P. Processos radiativos na atmosfera: fundamentos. São Paulo: Oficina de textos, 2016.

- Caption:

Circle (

) - refers to the measurement area;

Blue triangle (

) - refers to the lowest temperature point in the circled area; and

Red triangle (

) - refers to the highest temperature point in the circled area.

Edited by

-

Editor:

Enedir Ghisi

-

Editora de seção:

Luciani Somensi Lorenzi

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

16 May 2025 -

Date of issue

Jan-Dec 2025

History

-

Received

15 Oct 2024 -

Accepted

15 Dec 2024

Solar reflectance of cool concrete and fiber cement tiles and thermal performance analysis

Solar reflectance of cool concrete and fiber cement tiles and thermal performance analysis

Source: adapted from

Source: adapted from