Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is a ubiquitous nosocomial bacterium, which confers hospital-associated infections ranging from moderate to life-threatening disorders. The pathogenicity of the microorganism is attributed to various camouflage mechanisms harbored in its genome. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains have become significant pathogens in nosocomial and community settings. In the current study, we aimed to determine the prevalence of S. aureus, and more specifically, MRSA at different departments in four major hospitals in Jordan. A total of 500 inanimate surfaces located in the intensive care unit ICU, kidney department, surgery department, internal department, sterilization department, burn department, and operation department were swabbed. All isolates were identified by using routine bacterial culture, Gram staining, and a panel of biochemical tests such as; catalase, coagulase, DNase, urease, oxidase, and hemolysin production were performed. In terms of PCR, three main genes were screened, the 16S rRNA gene targeting Staphylococcus spp as a housekeeping gene, the coA gene was used as a specific gene to detect S. aureus, and the mecA gene used to identify MRSA isolates. Results revealed the prevalence of Staphylococcus spp was 212 (42.4%), S. aureus prevalence by coA gene 198 (39.6%), and MRSA by mecA gene in 81 samples (16.2%). There was a strong positive connection (P < 0.01) found between department site and bacterial contamination. It was concluded that inanimate hospital environments contain a relatively high number of S. aureus and MRSA. Proper sterilization techniques, infection prevention, and control management strategies should be implemented.

Keywords:

MRSA; Staphylococcus aureus; hospital control; antibiotic resistance; epidemiology.

Resumo

Staphylococcus aureus é uma bactéria nosocomial onipresente, que causa infecções hospitalares que variam de moderadas a potencialmente fatais. A patogenicidade do microrganismo é atribuída a vários mecanismos de camuflagem presentes em seu genoma. Cepas de Staphylococcus aureus resistentes à meticilina tornaram-se patógenos significativos em ambientes hospitalares e comunitários. No presente estudo, nosso objetivo foi determinar a prevalência de S. aureus e, mais especificamente, de MRSA em diferentes departamentos de quatro grandes hospitais da Jordânia. Um total de 500 superfícies inanimadas localizadas na unidade de terapia intensiva (UTI), departamento de nefrologia, departamento de cirurgia, departamento de medicina interna, departamento de esterilização, departamento de queimados e departamento de operações foram submetidas a coleta por swab. Todas as amostras foram identificadas usando cultura bacteriana de rotina, coloração de Gram e uma série de testes bioquímicos, como catalase, coagulase, DNase, urease, oxidase e hemolisina. Em termos de PCR, três genes principais foram analisados: o gene 16S rRNA direcionado a Staphylococcus spp como gene de manutenção, o gene coA foi usado como gene específico para detectar S. aureus e o gene mecA usado para identificar isolados de MRSA. Os resultados revelaram a prevalência de Staphylococcus spp em 212 (42,4%), a prevalência de S. aureus pelo gene coA em 198 (39,6%) e MRSA pelo gene mecA em 81 amostras (16,2%). Houve uma forte conexão positiva (P <0,01) encontrada entre o local do departamento e a contaminação bacteriana. Concluiu-se que os ambientes hospitalares inanimados contêm um número relativamente alto de S. aureus e MRSA. Devem ser implementadas técnicas adequadas de esterilização, prevenção de infecções e estratégias de gestão de controle.

Palavras-chave:

MRSA; Staphylococcus aureus; controle hospitalar; resistência a antibióticos; epidemiologia.

1. Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), a Gram-positive, non-motile, non-spore-forming microorganism quickly climbed to the highest spot on the list of healthcare-associated and hospital-acquired invasive infections (Akanbi et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2022; Eichenberger et al., 2020). S. aureus is a commensal bacterium that mostly inhabits the nasal cavities of humans and several animals (Parlet et al., 2019). Indeed, around 60% of the population has transient colonization from S. aureus, and 25–30% of persons have permanent colonization from this infection (Chmielowiec-Korzeniowska et al., 2020). S. aureus is linked to asymptomatic colonization of normal human skin and mucosal surfaces (Laux et al., 2019). Further, it is a primary source of wound infections and has the invasive capacity to cause osteomyelitis, endocarditis, and bacteremia. This can lead to secondary infections in any of the main organ systems (Tong et al., 2015). Many virulence factors that S. aureus possesses enable the bacterium to flourish in a variety of host environments and to survive extreme conditions (Balasubramanian et al., 2017). Enterotoxins and hemolysins are two examples of the virulence factors that S. aureus secretes and generates on its cell surface that contribute to the pathogenicity of the organism (Cheung et al., 2021).

S. aureus is one of the first organisms to become resistant to penicillin after it was introduced (Lobanovska and Pilla, 2017; Bashabsheh et al., 2023). Penicillin was replaced by methicillin, a novel semi-synthetic β-lactam antibiotic, which was released in 1959 (Kong et al., 2010; Odunitan et al., 2023). However, through acquisition of mobile genetic elements or chromosomal mutations has further complicated staphylococcal infections and therapeutics as the strains developed ways to limit the antibiotic’s activities (Howden et al., 2023). The acquisition of resistance to anti-staphylococcal penicillin through the mecA gene has resulted in the global dissemination of diverse lineages of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), now considered a global public health threat (Abu-Abaa et al., 2023; Tabaja et al., 2021). Indeed, MRSA was discovered in many cases within two years. Further, it was also discovered that these bacteria exhibited resistance against cefoxitin, oxacillin, and other β-lactam antibiotics (Algammal et al., 2020). Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) infections were often more common than MRSA infections, which were first discovered in hospitals (Jarajreh et al., 2017; Rosales-González et al., 2023). MRSA may express a wide range of pathogenic components, including endotoxins, capsules, iron-scavenging systems, siderophores, and adhesions (Patel and Rawat, 2023).

Undoubtedly, fomites contribute to the spread of Community Associated Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) infections, with inanimate items thought to be the infection's source and possible reservoir (Jaradat et al., 2020). Direct transfer can occur through contaminated hands or droplet transmission also considerable (Jaradat et al., 2020; Price et al., 2017). The infection may be retransmitted to fomites by bodily fluids from contaminated sites (Desai et al., 2011). According to several studies, MRSA may live on fomites for several hours, days, or even months, depending on the number of cells deposited there as well as other factors pertaining to the microstructure of the surfaces and the surrounding environment (Suleyman et al., 2018). A variety of molecular typing methods have been developed to track the spread of S. aureus infections and other pathogens (Al-Fawares et al., 2023). However, relatively few data exist on the molecular epidemiology of S. aureus, and MRSA strains. In the present study, the occurrence and characteristics of S. aureus and MRSA are investigated by collecting isolates from different environmental sources in four main hospitals in Jordan.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample collection

Using sterile swabs, 500 swab samples were obtained from four hospitals (Hospital 1, Hospital 2, Hospital 3, and Hospital 4), from June 2022 to August 2022. These included 125 samples from each hospital. Swabs were taken from different resources such as ventilation holes, devices used for patients, bed covers different surfaces of curtains, tables or beds of operating rooms, burns department, intensive care units, sterilization departments, nephrology and dialysis departments, internal medicine departments, and surgery departments. Using brain heart infusion broth transport medium (BHI), swabs were incubated for 24 hours at 35° C.

2.2. Identification of Staphylococcus aureus

Loopful from incubated swabs in BHI were sub-cultured onto Mannitol Salt Agar (MSA) (Oxoid Limited, England) and incubated at 37° C for 24 hours; Recovered mannitol fermenting and non-mannitol fermenting colonies were purified onto nutrient agar plate (HIMEDIA, India) (Moraes et al., 2021). According to the microbiology laboratory manual (2014), common microbiological tests for identifying suspected colonies were used (Varghese and Joy, 2014). The isolated bacterial colonies were identified by Gram staining (Moraes et al., 2021), Catalase test (Götz et al., 2006), Coagulase test (Thirunavukkarasu and Rathish, 2014), DNase test (Thirunavukkarasu and Rathish, 2014), Urease test (Zhou et al., 2019), Hemolysin production test (Moraes et al., 2021), Oxidase test (Moraes et al., 2021). All diagnostic tests were examined alongside the following reference strains: S. aureus (ATCC 29213) and MRSA (ATCC 1026) as positive controls. The suspected freshly isolated colonies were picked for purification and confirmation by microscopic examination and appropriate biochemical and growth tests.

2.3. Molecular identification using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

The isolates were cultured on nutrient agar and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours, after which a single colony was picked up with a sterile pipette tip without touching the agar and mixed with 50 μl of endonuclease-free water, then heated at 100 °C for 15 minutes. The Nanodrop (Thermo-fisher, US) was used to quantify the quantity and purity of the DNA. (Shahmoradi et al., 2019). Conventional PCR protocol targets three genes namely 16S rRNA gene (genus-specific Staphylococcal spp, coA (specific gene for S. aureus), and mecA (specific gene for MRSA). Primers are shown in Table 1. I-Taq master mix (Easy Taq, China) was utilized to conduct PCR. The reaction mixture's final volume was 25 µl in which 12.5-µl master mix was added to a sterile PCR tube containing 1.5 µl of each primer of a 10-µM primer concentration. Five-μl template DNA was added and the volume was completed to 25 µl by adding 4.5 µl of nuclease-free water. The reaction conditions in the thermocycler (Bio-Rad, USA) were as follows: initial denaturalization at 95 °C for 3 min; 45 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 sec; Specific annealing temperature for each primer for 30 sec; extension at 72 °C for 1 min. Subsequently, a 2% final concentration of agarose gel was prepared (2 g in 100 mL Tris Borate EDTA (TBE buffer), stained with 3 µl ethidium bromide, and put onto the tray. A 100 bp DNA standard ladder was used, and each well was filled with 3 µl from each reaction mixture. The PCR products were photographed with a gel documentation system (Gel Doc 2000, Bio-Rad, USA) and observed with a UV transilluminator after the electrophoresis devices was run for 30 minutes at 170 volts.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data was processed using the SPSS software version 19.0 (2009; Chicago, IL, USA). To investigate the prevalence of Staphylococcal spp., S. aureus, and MRSA, one way ANOVA and homogeneous subsets were used. Chai square correlation was implemented to study the Pearson correlation between the dependent and independent variables. The statistical significance cut-off value was set at P value <0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Microbial distribution among study samples.

Three hundred and twenty-seven (65%) of the 500 environmental samples that were collected from four distinct hospital sites in Jordan were cultured on MSA and contained Staphylococcal colonies, as the changing of color from red to yellow was an indication of the fermentation process carried out by staphylococci. Identification was performed on them using different biochemical tests. The results revealed the prevalence of Staphylococcus spp in general was 212 (42.4%), S. aureus prevalence by coA gene 198 (39.6%), and MRSA by mecA gene in 81 samples (16.2%), (Table 2).

In-depth, colonies that were grown on MSA medium were subjected to Gram stain, catalase, and coagulase, DNase, and urease tests. Supplementary Table S1 presents the biochemical characterization of 327 isolates. The results showed that 213 isolates tested positive for urease, DNase, and coagulase, while all 327 isolates tested positive for catalase. Still, S. aureus was assigned to the 213 isolates. The antimicrobial sensitivity of the S. aureus isolates against cefoxitin antibiotic was evaluated in this study. The data showed that 121 isolates had inhibition zones of less than 22 mm and were fully sensitive to cefoxitin. The highest frequency of resistance was observed for 92 isolates were the inhibition zones ≤ 21, which considered methicillin-oxacillin resistance, isolates (Figure S1). To differentiate between the Staphylococcus species isolated from the hospital environment. One housekeeping gene and two species-specific genes were utilized in PCR. The 16S rRNA gene specific for Staphylococcus spp, the coA gene specific for S. aureus, and the mecA gene specific for MRSA isolates were used. In this study, out of 327 samples grown on MSA media, 213 representative Staphylococcus isolates that were biochemically validated were further characterized at the molecular level through the amplification of the 16S rRNA gene and demonstrated a specific product with 218 bp as a housekeeping gene for Staphylococcus spp (Figure S2). The PCR test confirmed the biochemical test results. Molecular data revealed that 198 Staphylococcus exhibit 600-850 bp products specific for the coA gene (Figure S3). The detection of the coA gene by PCR is considered standard for S. aureus identification. Eighty-one isolates of S. aureus were positive for the mecA gene based on PCR detection of a 531 bp amplicon (Figure S4). mecA gene is specific for the identification of MRSA.

3.2. Distribution of S. aureus among different sites

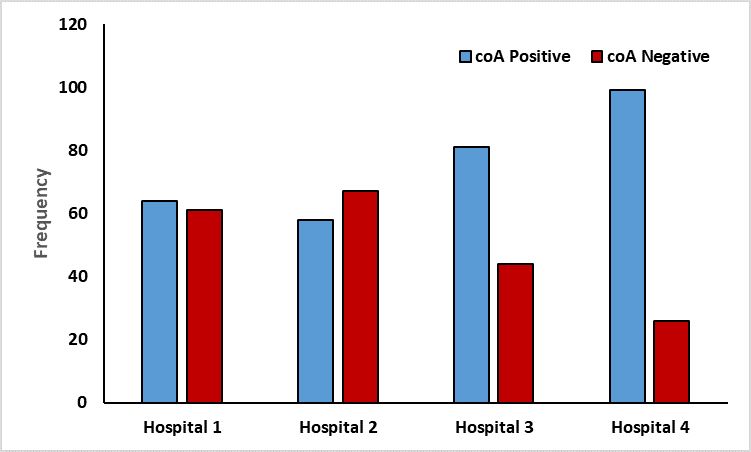

Environmental samples from Hospitals 2 (67), 1 (61), and 3 (44) had the highest concentration of S. aureus. Low S. aureus occurrence (26) was observed in the sample taken from Hospital 4, as Figure 1 illustrates.

3.3. Distribution of MRSA among different site

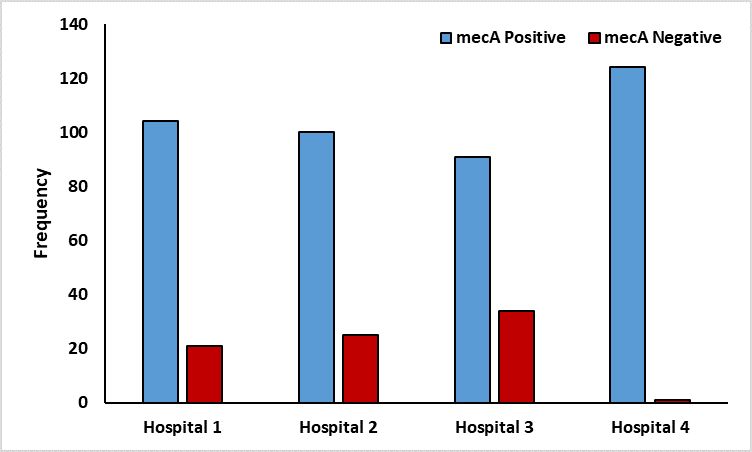

Figure 2 shows that 81 MRSAs were found among the 198 S. aureus isolates. Hospital 3 had the highest number of MRSA isolates (34), followed by Hospital 2 with (25) and Hospital 1 with (21). One isolate was isolated from Hospital 4. These results revealed different sites have a significant correlation with the contaminations of S. aureus and MRSA (P <0.01).

3.4. Distribution of S. aureus among different departments

From the total 500 swab samples, the highest bacterial contamination rate was observed in Kidney department 41(97.6%), followed by Internal department 38(90%), Surgery department 60(68%), ICU 120(58.5%), Burn department 47(58.4%) and in Sterilization department 16(45.7%). The lowest was detected in Operation Department 5(15%). The positive rates of each study participant are summarized in Table 3.

Proportion of bacterial isolates from different departments that exhibit colony growth on MSA media.

3.5. Distribution of S. aureus among different sub-departments

Out of 198 S. aureus isolated, 13 were isolated from the Burn department, 12 from ICU and heart surgery, 18 from ICU burns, 20 from the ICU department, 17 from the internal ICU, and 10 from the kidney department-installation room (Figure 3, Supplementary Table S2).

3.6. Distribution of MRSA among different sub-departments

There were 81 MRSA isolates: 10 from the Burn department, 11 from the ICU and heart surgery, 13 from the surgery department, 6 from the internal medicine department, 6 from the SICU, and 10 from the men's surgery department (Figure 4, Supplementary Table S3). These results revealed different departments and sub-departments have a significant correlation with the contaminations of S. aureus and MRSA (P <0.01).

4. Discussion

Diversity in MRSA epidemiology is a major public health problem. Yet, despite several studies showing a greater prevalence of MRSA colonization in hospital settings compared to community settings, there are no precise distinguishing criteria for the identification of MRSA origin (Romero and Souza da Cunha, 2021). Comparatively little is known about the dynamics of S. aureus or MRSA colonization in nonhuman primates, which are essential study models for human disease (Soge et al., 2016). This study set out to assess the prevalence of S. aureus and MRSA in Jordanian hospital departments and critical care units. Understanding the level of contamination in the hospital environment through evidence-based information is essential for the successful prevention and management of hospital-acquired diseases (Kubde et al., 2023). Thus, we targeted different freshly isolated hospital bacteria, identified and characterized the S. aureus from them, tested the sensitivity of these S. aureus isolates to different antibiotics, and finally evaluated the distributions of MRSA.

In the current study, 327 of the 500 environmental swabs had grown. Through biochemical identification and molecular confirmation of the data, there were 42.4% positive Staphylococci, and among these isolates around 60% were S. aureus. However, a previous study conducted in the indoor environment at King Abdullah University Hospital in Jordan shows that S. aureus made up (28%) of all isolated Staphylococcus (79%), which was the most prevalent bacteria in operating rooms (OT), intensive care units (ICU), and nursery intensive care units (NICU) units (Saadoun et al., 2015). Furthermore, 86% of the 129 samples taken from critical care units and healthcare workers in a district hospital in Jordan in 2021 for the purpose of mapping the environment and health care staff there were positive for S. aureus (Al-Essa et al., 2021). Nonetheless, an Irish report reveals that the prevalence of S. aureus in hospital samples was 16% in air samples and 7.9% in surface samples (Kearney et al., 2020). Furthermore, the rate of S. aureus environmental colonization was 12.4% in a research conducted in 2019 to assess the incidence of the bacteria colonizing patients as well as the ICU environment of a teaching hospital in Brazil (Veloso et al., 2019). A 2015 research found that in two large hospitals in Palestine, the prevalence of S. aureus was 23.1% and 37.4%, respectively (Adwan et al., 2015). Jarajreh et al., research revealed that (56.3%) of isolates were S. aureus from two hospitals in Jordan (Jarajreh et al., 2017).

Bacterial multi-drug resistance may be intrinsic, resulting from a stable genetic trait and encoded chromosomally (AL-Fawares et al., 2024). Extrinsic resistance to this is caused by changes in the acquired genome, passed on to other bacteria, for example by conjugation, transduction, or transformation. The risk of MDR contamination is high on environmental surfaces and equipment in immediate contact with colonized patients, and healthcare workers are crucial in the transmission of responsible microorganisms, according to a significant study (Valzano et al., 2024). MDR forms of S. aureus, in particular MRSA, pose a significant clinical and epidemiological problem. There have been numerous reports that various items in hospitals could be sources of MRSA transmission (Shoaib et al., 2023). According to molecular identification by PCR, which finds the presence of the mecA gene, the incidence of MRSA in the current investigation was 16.2% across all samples. In contrast to a research assessing the prevalence of MRSA in Ireland, in 2020 the study's environmental sample collection from acute hospitals in Dublin revealed 2.2% of surface samples and 2.5% of air samples included MRSA (Kearney et al., 2020). A different research found that hospitals in Tabriz, Iran, had a 76.95 percent MRSA prevalence (Hasanpour et al., 2023).

In the previously mentioned study, which was carried out in Palestine, MRSA prevalence among S. aureus was 29% and 8.2% (Adwan et al., 2015). A previously reported research carried out at King Abdullah University Hospital in Jordan found that the prevalence rates of MRSA in the ICU, NICU, and OT were 4.2%, 3.1%, and 2%, respectively (Saadoun et al., 2015). As well a study in southern regions of Jordan the prevalence of MRSA was (77.5%) (Jarajreh et al., 2017). However, several things, including, the region, the size of samples, hygiene and sterilization, and many variables may lead to a discrepancy in proportions between different studies. The increased frequency of MRSA on environmental surfaces at Jordan's public hospitals might be caused by a number of factors (Abdelmalek et al., 2021; Abdulla et al., 2018; Abu Dayyih et al., 2020). The high frequency of MRSA in hospitals is mostly due to antibiotic abuse, which creates an environment that is favorable to the growth of MRSA. During their hospital stay, patients are often given many antibiotics, which might encourage the growth and spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Hospitals are additionally overcrowded environments where patients, healthcare workers, and visitors frequently come into contact. As a result, MRSA can transmit from person to person or from contaminated surfaces to people. Hospitals might not have implemented efficient infection control procedures to prevent the spread of MRSA, which is another explanation. This can include insufficient hand hygiene, improper cleaning and disinfection of equipment and surfaces, and inadequate isolation precautions. As MRSA can survive on surfaces for extended periods, and can be spread through contact with contaminated surfaces. Thus, bedrails, medical equipment, and bathroom fixtures are examples of shared surfaces and equipment that might increase the transmission of MRSA in hospitals. To prevent the transmission of MRSA, these surfaces must be properly cleaned and disinfected (Hughes et al., 2013).

5. Conclusion

The pooled prevalence of MRSA from inanimate surfaces in four different Jordanian hospitals was remarkably high. This could be attributed to the improper use of antibiotics or the lack of a prescription selection guideline. It could be connected to improper cleaning methods and a lack of instruction on the most effective ways to regularly target cleaning high-touch surfaces. Therefore, we recommend that appropriate levels of sanitation and control protocols be employed. These precautions include routine hand washing, sporadic medical equipment cleaning, and sterilization.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material accompanies this paper.

Figure S1.

Figure S2.

Figure S3.

Figure S4.

Table S1.

Table S2.

Table S3.

This material is available as part of the online article from https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.285397

References

-

ABDELMALEK, S., ALEJIELAT, R., RAYYAN, W.A., QINNA, N. and DARWISH, D., 2021. Changes in public knowledge and perceptions about antibiotic use and resistance in Jordan: a cross-sectional eight-year comparative study. BMC Public Health, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 750. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10723-x PMid:33874935.

» http://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10723-x -

ABDULLA, M., MALLAH, E., DAYYIH, W.A., RAYYAN, W.A., EL-HAJJI, F.D., BUSTAMI, M., MANSOUR, K., AL-ANI, I., SEDER, N. and ARAFAT, T., 2018. Influence of energy drinks on pharmacokinetic parameters of sildenafil in rats. Biomedical & Pharmacology Journal, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 1317-1328. http://doi.org/10.13005/bpj/1494

» http://doi.org/10.13005/bpj/1494 -

ABU DAYYIH, W., ABU RAYYAN, W. and AL-MATUBSI, H.Y., 2020. Impact of sildenafil-containing ointment on wound healing in healthy and experimental diabetic rats. Acta Diabetologica, vol. 57, no. 11, pp. 1351-1358. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-020-01562-0 PMid:32601730.

» http://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-020-01562-0 - ABU-ABAA, M., PULIKEYIL, A., ARSHAD, H. and GOLDSMITH, D., 2023. Primary MRSA myositis mimicking septic arthritis. Case Reports in Critical Care, vol. 2023, pp. 5623876. http://doi.org/10.1155/2023/5623876. PMid:36895204.

- ADWAN, G., SHAHEEN, H., ADWAN, K. and BARAKAT, A., 2015. Molecular characterization of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from hospitals environments and patients in Northern Palestine. Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Public Health, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 1-21. http://doi.org/10.2427/11183.

-

AKANBI, O.E., NJOM, H.A., FRI, J., OTIGBU, A.C. and CLARKE, A.M., 2017. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from recreational waters and beach sand in Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 14, no. 9, pp. 1001. http://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14091001 PMid:28862669.

» http://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14091001 - AL-ESSA, L., ABUNAJA, M.H., HAMADNEH, L. and ABU-SINI, M., 2021. Mapping the intensive care unit environment and health care workers for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with mecA gene confirmation and antibacterial resistance pattern identification in a district hospital in Amman. The Kuwait Medical Journal, vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 265-270.

- AL-FAWARES, O., AL-KHRESIEH, R.O., ABURAYYAN, W., SEDER, N., AL-DAGHISTANI, H.I., EL-BANNA, N. and ABU-TALEB, E.M., 2023. Comparison of preservation enrichment media for long storage duration of Campylobacter jejuni The Korean Journal of Microbiology, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 192-196.

-

AL-FAWARES, O., ALSHWEIAT, A., AL-KHRESIEH, R.O., ALZARIENI, K.Z. and RASHAID, A.H.B., 2024. A significant antibiofilm and antimicrobial activity of chitosan-polyacrylic acid nanoparticles against pathogenic bacteria. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 101918. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.101918 PMid:38178849.

» http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.101918 -

ALGAMMAL, A.M., HETTA, H.F., ELKELISH, A., ALKHALIFAH, D.H.H., HOZZEIN, W.N., BATIHA, G.E.-S., EL NAHHAS, N. and MABROK, M.A., 2020. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): one health perspective approach to the bacterium epidemiology, virulence factors, antibiotic-resistance, and zoonotic impact. Infection and Drug Resistance, vol. 13, pp. 3255-3265. http://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S272733 PMid:33061472.

» http://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S272733 -

BALASUBRAMANIAN, D., HARPER, L., SHOPSIN, B. and TORRES, V.J., 2017. Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis in diverse host environments. Pathogens and Disease, vol. 75, no. 1, pp. ftx005. http://doi.org/10.1093/femspd/ftx005 PMid:28104617.

» http://doi.org/10.1093/femspd/ftx005 - BASHABSHEH, R.H.F., AL-FAWARES, O., NATSHEH, I., BDEIR, R., AL-KHRESHIEH, R.O. and BASHABSHEH, H.H.F., 2023. Staphylococcus aureus epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and application of nano-therapeutics as a promising approach to combat methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus Pathogens and Global Health, vol. 118, no. 3, pp. 209-231. http://doi.org/10.1080/20477724.2023.2285187. PMid:38006316.

-

CHEN, H., ZHANG, J., HE, Y., LV, Z., LIANG, Z., CHEN, J., LI, P., LIU, J., YANG, H., TAO, A. and LIU, X., 2022. Exploring the role of Staphylococcus aureus in inflammatory diseases. Toxins, vol. 14, no. 7, pp. 464. http://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14070464 PMid:35878202.

» http://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14070464 -

CHEUNG, G.Y.C., BAE, J.S. and OTTO, M., 2021. Pathogenicity and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus Virulence, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 547-569. http://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2021.1878688 PMid:33522395.

» http://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2021.1878688 -

CHMIELOWIEC-KORZENIOWSKA, A., TYMCZYNA, L., WLAZŁO, Ł., NOWAKOWICZ-DĘBEK, B. and TRAWIŃSKA, B., 2020. Staphylococcus aureus carriage state in healthy adult population and phenotypic and genotypic properties of isolated strains. Postepy Dermatologii i Alergologii, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 184-189. http://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2020.94837 PMid:32489352.

» http://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2020.94837 -

DESAI, R., PANNARAJ, P.S., AGOPIAN, J., SUGAR, C.A., LIU, G.Y. and MILLER, L.G., 2011. Survival and transmission of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from fomites. American Journal of Infection Control, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 219-225. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2010.07.005 PMid:21458684.

» http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2010.07.005 -

EICHENBERGER, E.M., SHOFF, C.J., ROLFE, R., PAPPAS, S., TOWNSEND, M. and HOSTLER, C.J., 2020. Staphylococcus aureus prostatic abscess in the setting of prolonged S. aureus bacteremia. Case Reports in Infectious Diseases, vol. 2020, pp. 7213838. http://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7213838 PMid:32518699.

» http://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7213838 -

GÖTZ, F., BANNERMAN, T. and SCHLEIFER, K.-H., 2006. The genera Staphylococcus and Macrococcus In: M. DWORKIN, S. FALKOW, E. ROSENBERG, K.H. SCHLEIFER and E. STACKEBRANDT, eds. The Prokaryotes New York: Springer. http://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-30744-3_1

» http://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-30744-3_1 -

HASANPOUR, A.H., SEPIDARKISH, M., MOLLALO, A., ARDEKANI, A., ALMUKHTAR, M., MECHAAL, A., HOSSEINI, S.R., BAYANI, M., JAVANIAN, M. and ROSTAMI, A., 2023. The global prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in residents of elderly care centers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1-11. http://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-023-01210-6 PMid:36709300.

» http://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-023-01210-6 -

HOWDEN, B.P., GIULIERI, S.G., WONG FOK LUNG, T., BAINES, S.L., SHARKEY, L.K., LEE, J.Y.H., HACHANI, A., MONK, I.R. and STINEAR, T.P., 2023. Staphylococcus aureus host interactions and adaptation. Nature Reviews. Microbiology, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 380-395. http://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00852-y PMid:36707725.

» http://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00852-y - HUGHES, C., TUNNEY, M. and BRADLEY, M.C., 2013. Infection control strategies for preventing the transmission of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in nursing homes for older people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, vol. 2013, no. 11, pp. CD006354. http://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006354.pub4.

-

JARADAT, Z.W., ABABNEH, Q.O., SHA’ABAN, S.T., ALKOFAHI, A.A., ASSALEH, D. and AL SHARA, A., 2020. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and public fomites: a review. Pathogens and Global Health, vol. 114, no. 8, pp. 426-450. http://doi.org/10.1080/20477724.2020.1824112 PMid:33115375.

» http://doi.org/10.1080/20477724.2020.1824112 -

JARAJREH, D., AQEL, A., ALZOUBI, H. and AL-ZEREINI, W., 2017. Prevalence of inducible clindamycin resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: the first study in Jordan. Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 350-354. http://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.8316 PMid:28459227.

» http://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.8316 -

KEARNEY, A., KINNEVEY, P., SHORE, A., EARLS, M., POOVELIKUNNEL, T.T., BRENNAN, G., HUMPHREYS, H. and COLEMAN, D.C., 2020. The oral cavity revealed as a significant reservoir of Staphylococcus aureus in an acute hospital by extensive patient, healthcare worker and environmental sampling. The Journal of Hospital Infection, vol. 105, no. 3, pp. 389-396. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2020.03.004 PMid:32151672.

» http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2020.03.004 -

KONG, K.-F., SCHNEPER, L. and MATHEE, K., 2010. Beta-lactam antibiotics: from antibiosis to resistance and bacteriology. Acta Pathologica, Microbiologica, et Immunologica Scandinavica, vol. 118, no. 1, pp. 1-36. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0463.2009.02563.x PMid:20041868.

» http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0463.2009.02563.x - KUBDE, D., BADGE, A.K., UGEMUGE, S. and SHAHU, S., 2023. Importance of hospital infection control. Cureus, vol. 15, no. 12, e50931. http://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.50931. PMid:38259418.

-

LAUX, C., PESCHEL, A. and KRISMER, B., 2019. Staphylococcus aureus colonization of the human nose and interaction with other microbiome members. Microbiology Spectrum, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 7.2.34. http://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0029-2018 PMid:31004422.

» http://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0029-2018 - LOBANOVSKA, M. and PILLA, G., 2017. Penicillin’s discovery and antibiotic resistance: lessons for the future? The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, vol. 90, no. 1, pp. 135-145. PMid:28356901.

- MORAES, G.F.Q., CORDEIRO, L.V. and DE ANDRADE JÚNIOR, F.P., 2021. Main laboratory methods used for the isolation and identification of Staphylococcus spp Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Quimico-Farmaceuticas, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 5-28. http://doi.org/10.15446/rcciquifa.v50n1.95444.

- ODUNITAN, T.T., OYARONBI, A.O., ADEBAYO, F.A., ADEKOYENI, P.A., APANISILE, B.T., OLADUNNI, T.D. and SAIBU, O.A., 2023. Antimicrobial peptides: a novel and promising arsenal against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. Pharmaceutical Science Advances, vol. 2, pp. 100034. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscia.2023.100034.

-

PARLET, C.P., BROWN, M.M. and HORSWILL, A.R., 2019. Commensal staphylococci influence Staphylococcus aureus skin colonization and disease. Trends in Microbiology, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 497-507. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2019.01.008 PMid:30846311.

» http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2019.01.008 -

PATEL, H. and RAWAT, S., 2023. A genetic regulatory see-saw of biofilm and virulence in MRSA pathogenesis. Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 14, pp. 1204428. http://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1204428 PMid:37434702.

» http://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1204428 -

PRICE, J.R., COLE, K., BEXLEY, A., KOSTIOU, V., EYRE, D.W., GOLUBCHIK, T., WILSON, D.J., CROOK, D.W., WALKER, A.S., PETO, T.E.A., LLEWELYN, M.J. and PAUL, J., 2017. Transmission of Staphylococcus aureus between health-care workers, the environment, and patients in an intensive care unit: a longitudinal cohort study based on whole-genome sequencing. The Lancet. Infectious Diseases, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 207-214. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30413-3 PMid:27863959.

» http://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30413-3 -

ROMERO, L.C. and SOUZA DA CUNHA, M.L.R., 2021. Insights into the epidemiology of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in special populations and at the community-healthcare interface. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 101636. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2021.101636 PMid:34672988.

» http://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2021.101636 -

ROSALES-GONZÁLEZ, N. C., GONZÁLEZ-MARTÍN, M., NASIR ABDULLAHI, I., TEJEDOR-JUNCO, M. T., LATORRE-FERNÁNDEZ, J. and TORRES, C., 2023. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, and genetic lineages of nasal Staphylococcus aureus among medical students at a Spanish University: detection of the MSSA-CC398-IEC-type-C subclade. Research in Microbiology, vol. 175, no. 4, pp. 104176. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmic.2023.104176 PMid:38141795.

» http://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmic.2023.104176 -

SAADOUN, I., JARADAT, Z.W., AL TAYYAR, I.A., EL NASSER, Z. and ABABNEH, Q., 2015. Airborne methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the indoor environment of King Abdullah University Hospital, Jordan. Indoor and Built Environment, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 315-323. http://doi.org/10.1177/1420326X14526604

» http://doi.org/10.1177/1420326X14526604 - SHAHMORADI, M., FARIDIFAR, P., SHAPOURI, R., MOUSAVI, S.F., EZZEDIN, M. and MIRZAEI, B., 2019. Determining the biofilm forming gene profile of Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates via multiplex colony PCR method. Reports of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 181-188. PMid:30805398.

-

SHOAIB, M., AQIB, A.I., MUZAMMIL, I., MAJEED, N., BHUTTA, Z.A., KULYAR, M.F.A., FATIMA, M., ZAHEER, C.N.F., MUNEER, A., MURTAZA, M., KASHIF, M., SHAFQAT, F. and PU, W., 2023. MRSA compendium of epidemiology, transmission, pathophysiology, treatment, and prevention within one health framework. Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 13, pp. 1067284. http://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1067284 PMid:36704547.

» http://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1067284 -

SOGE, O.O., NO, D., MICHAEL, K.E., DANKOFF, J., LANE, J., VOGEL, K., SMEDLEY, J. and ROBERTS, M.C., 2016. Transmission of MDR MRSA between primates, their environment and personnel at a United States primate centre. The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, vol. 71, no. 10, pp. 2798-2803. http://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkw236 PMid:27439524.

» http://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkw236 -

SULEYMAN, G., ALANGADEN, G. and BARDOSSY, A.C., 2018. The role of environmental contamination in the transmission of nosocomial pathogens and healthcare-associated infections. Current Infectious Disease Reports, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 12. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-018-0620-2 PMid:29704133.

» http://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-018-0620-2 -

TABAJA, H., HINDY, J.R. and KANJ, S.S., 2021. Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Arab countries of the middle east and North African (Mena) region. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases, vol. 13, no. 1, e2021050. http://doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2021.050 PMid:34527202.

» http://doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2021.050 - THIRUNAVUKKARASU, S. and RATHISH, K.C., 2014. Evaluation of direct tube coagulase test in diagnosing Staphylococcal bacteremia Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 19-21. http://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/6687.4371. PMid:24995177.

-

TONG, S.Y.C., DAVIS, J.S., EICHENBERGER, E., HOLLAND, T.L. and FOWLER JUNIOR, V.G.J., 2015. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 603-661. http://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00134-14 PMid:26016486.

» http://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00134-14 -

VALZANO, F., CODA, A.R.D., LISO, A. and ARENA, F., 2024. Multidrug-resistant bacteria contaminating plumbing components and sanitary installations of hospital restrooms. Microorganisms, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 136. http://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12010136 PMid:38257963.

» http://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12010136 - VARGHESE, N. and JOY, P.P., 2014. Microbiology laboratory manual Ernakulam District: Kerala Agricultural University.

-

VELOSO, J.O., LAMARO-CARDOSO, J., NEVES, L.S., BORGES, L.F.A., PIRES, C.H., LAMARO, L., GUERREIRO, T.C., FERREIRA, E.M.A. and ANDRÉ, M.C.P., 2019. Methicillin-resistant and vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus colonizing patients and intensive care unit environment: virulence profile and genetic variability. APMIS, vol. 127, no. 11, pp. 717-726. http://doi.org/10.1111/apm.12989 PMid:31407405.

» http://doi.org/10.1111/apm.12989 -

ZHOU, C., BHINDERWALA, F., LEHMAN, M.K., THOMAS, V.C., CHAUDHARI, S.S., YAMADA, K.J., FOSTER, K.W., POWERS, R., KIELIAN, T. and FEY, P.D., 2019. Urease is an essential component of the acid response network of Staphylococcus aureus and is required for a persistent murine kidney infection. PLoS Pathogens, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1-23. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1007538 PMid:30608981.

» http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1007538

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

31 Jan 2025 -

Date of issue

2024

History

-

Received

09 Apr 2024 -

Accepted

01 Oct 2024

Molecular investigation of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from inanimate surfaces in Jordanian hospitals

Molecular investigation of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from inanimate surfaces in Jordanian hospitals