Abstract

According to previous studies, the Palaeoproterozoic Minas-Itacolomi meta-sedimentary mega-sequence in the Quadrilátero Ferrífero metallogenic province records the transition of a continental rift to passive margin to foreland basin. From the perspective of sequence stratigraphy, this article identifies five sequences summarised in the Minas-Itacolomi Basin stratigraphic chart, providing information of the Palaeoproterozoic eustatic changes, such as the Great Oxidation Event. Interpretations were based on the systematic recognition of 41 facies and their associations, the identification of nine recurring depositional systems, nine system tracts, and five sequences (in that order). The Caraça and Itabira Groups comprise the first sequence, for which three system tracts were identified. The Piracicaba Group hosts two sequences and four system tracts. The Sabará and Itacolomi Groups are the two upper sequences, both related to a foreland basin, where the underfilled and overfilled system tracts were recognised. Sedimentary provenance was determined mainly from detrital zircon U-Pb age spectra of previous authors’ databases, as well as on palaeocurrent field data and thickness variations. All of the units of the Minas-Itacolomi mega-sequence share detrital zircons from Archaean sources (Rio das Velhas Supergroup and crystalline basement). Only the Sabará and Itacolomi Groups exhibited bimodal U-Pb age histograms, thus indicating both Archaean and Palaeoproterozoic (Mineiro Belt) provenances.

KEYWORDS:

sedimentary facies; Palaeoproterozoic Minas-Itacolomi Basin; sequence stratigraphy; sedimentary geology

INTRODUCTION

Sedimentary basins are regions where sediment accumulates into successions of hundreds to thousands of metres thick over large areas. The sedimentary rocks in a basin provide a record of both the tectonic history of the area and the effects of other controls on deposition, such as climate, sea base level, and sediment supply (Catuneanu 2006Catuneanu O. 2006. Principles of sequence stratigraphy. Elsevier, 376 p., Nichols 2009Nichols G. 2009. Sedimentology and stratigraphy. 2ª ed. Wiley Blackwell, 419 p.).

The Palaeoproterozoic Minas-Itacolomi basins are a good example of several sedimentary successions controlled by tectonics. Their stratigraphic units are located within the Iron Quadrangle (acronyms: IQ or QF, for “Quadrilátero Ferrífero”, in Portuguese), in the state of Minas Gerais, South East of Brazil. The QF is one of Brazil’s most important metallogenic provinces, as it hosted many world-class Au deposits, as well as Lake Superior and Algoma type banded iron formations, and uranium palaeoplacers deposits, not to mention, its many similarities to the Transvaal Sequence, in South Africa (Villaça and Moura 1985Villaça J.N., Moura L.A.M. 1985. O urânio e o ouro da Formação Moeda, Minas Gerais. In: Schobbenhaus C., Coelho C.E.S. (coords.). Principais Depósitos Minerais do Brasil. DNPM-CVRD, v. 1, p. 177-187., Minter et al. 1990Minter W.E.L., Renger F.E., Siegers A. 1990. Early proterozoic gold placers of the moeda formation within the gandarela syncline, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Economic Geology, 85(5):943-951. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsecongeo.85.5.943

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2113/...

, Renger et al. 1994Renger F.E., Noce C.M., Romano A.W., Machado N. 1994. Evolução sedimentar do Supergrupo Minas: 500 Ma de registro geológico no Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais, Brasil. Geonomos, 2(1):1-11. https://doi.org/10.18285/geonomos.v2i1.227

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18285...

, Lobato et al. 2000Lobato L.M., Ribeiro Rodrigues L.C., Zucchetti M., Baltazar O.F. 2000. Geology and gold mineralization in the Rio das Velhas Greenstone Belt, Quadrilátero Ferrífero (Minas Gerais, Brazil). In: 31º International Geological Congress. Field Trip Guide, 40 p., Vial et al. 2007Vial D.S., Groves D.I., Cook N.J., Lobato L.M. 2007. Preface - Special issue on gold deposits of Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Ore Geology Reviews, 32(3-4):469-470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2006.11.006

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

). There are few papers in the literature that focus on sedimentary facies description and depositional system identification in the Minas-Itacolomi basins. This article presents the sequence stratigraphy approach of Minas-Itacolomi sedimentation through the description of its sedimentary geology or, more specifically, through facies description, depositional systems interpretation, as well as system tracts and sequences correlations, in order to aid further in the geological evolution and time relationships of those basins.

The chronological relationships within Minas-Itacolomi are hard to be obtained precisely and accurately due to the lack of index fossils and the absence of cross-cutting and/or interlayered igneous rocks for isotope dating (Noce 2000Noce C.M. 2000. Geochronology of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero: a review. Geonomos, 8(1):15-23. https://doi.org/10.18285/geonomos.v8i1.144

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18285...

, Dopico et al. 2017Dopico C.I.M., Lana C., Moreira H.S., Cassino L.F., Alkmim F.F. 2017. U-Pb ages and Hf-isotope data of detrital zircons from the late Neoarchean-Paleoproterozoic Minas Basin, SE Brazil. Precambrian Research, 291:143-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2017.01.026

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Dutra et al. 2019Dutra L.F., Martins M., Lana C. 2019. Sedimentary and U-Pb detrital zircons provenance of the Paleoproterozoic Piracicaba and Sabará groups, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Southern São Francisco craton, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Geology, 49(2):e20180095. https://doi.org/10.1590/2317-4889201920180095

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/...

). To overcome this major problem, sedimentary provenance geochronological studies regarding detrital zircons have been carried out to estimate the life span of the sedimentary basins (Renger et al. 1994Renger F.E., Noce C.M., Romano A.W., Machado N. 1994. Evolução sedimentar do Supergrupo Minas: 500 Ma de registro geológico no Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais, Brasil. Geonomos, 2(1):1-11. https://doi.org/10.18285/geonomos.v2i1.227

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18285...

, Machado et al. 1996Machado N., Schrank A., Noce C.M., Gauthier G. 1996. Ages of detrital zircon from Archean-Paleoproterozoic sequences: Implications for Greenstone Belt setting and evolution of a Transamazonian foreland basin in Quadrilátero Ferrífero, southeast Brazil. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 141(1-4):259-276. https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-821X(96)00054-4

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Hartmann et al. 2006Hartmann L.A., Endo I., Suita M.T.F., Santos J.O.S., Frantz J.C., Carneiro M.A., McNaughton N.J., Barley M.E. 2006. Provenance and age delimitation of Quadrilátero Ferrífero sandstones based on zircon U-Pb isotopes. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 20(4):273-285., Koglin et al. 2014Koglin N., Zeh A., Cabral A.R., Gomes A.A.S., Corrêa Neto A.V., Brunetto W.J., Galbiatti H. 2014. Depositional age and sediment source of the auriferous Moeda Formation, Quadrilátero Ferrífero of Minas Gerais, Brazil: New constraints from U-Pb-Hf isotopes in zircon and xenotime. Precambrian Research, 255(Part 1):96-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2014.09.010

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Mendes et al. 2014Mendes M.C.O., Lobato L.M., Suckau V., Lana C. 2014. In situ LA-ICPMS U-Pb dating of detrital zircons from the Cercadinho Formation, Minas Supergroup. Geologia USP. Série Científica, 14(1):65-68. https://doi.org/10.5327/Z1519-874X201400010004

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5327/...

, Nunes 2016Nunes F.S. 2016. Contribuição à estratigrafia e geocronologia U-Pb de zircões detríticos da Formação Moeda (Grupo Caraça, Supergrupo Minas) na Serra do Caraça, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais. Master of Science Dissertation, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto., Dopico et al. 2017Dopico C.I.M., Lana C., Moreira H.S., Cassino L.F., Alkmim F.F. 2017. U-Pb ages and Hf-isotope data of detrital zircons from the late Neoarchean-Paleoproterozoic Minas Basin, SE Brazil. Precambrian Research, 291:143-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2017.01.026

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Dutra et al. 2019Dutra L.F., Martins M., Lana C. 2019. Sedimentary and U-Pb detrital zircons provenance of the Paleoproterozoic Piracicaba and Sabará groups, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Southern São Francisco craton, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Geology, 49(2):e20180095. https://doi.org/10.1590/2317-4889201920180095

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/...

). Furthermore, this article also presents a detrital zircon age data compilation (database from Machado et al. 1992Machado N., Noce C.M., Ladeira E.A., Oliveira O.A.B. 1992. U-Pb geochronology of the Archean magmatism and Proterozoic metamorphism in the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, southern São Francisco Craton, Brazil. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 104(9):1221-1227. https://doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606(1992)104%3C1221:UPGOAM%3E2.3.CO;2

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1130/...

, Machado et al. 1996Machado N., Schrank A., Noce C.M., Gauthier G. 1996. Ages of detrital zircon from Archean-Paleoproterozoic sequences: Implications for Greenstone Belt setting and evolution of a Transamazonian foreland basin in Quadrilátero Ferrífero, southeast Brazil. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 141(1-4):259-276. https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-821X(96)00054-4

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Hartmann et al. 2006Hartmann L.A., Endo I., Suita M.T.F., Santos J.O.S., Frantz J.C., Carneiro M.A., McNaughton N.J., Barley M.E. 2006. Provenance and age delimitation of Quadrilátero Ferrífero sandstones based on zircon U-Pb isotopes. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 20(4):273-285., Koglin et al. 2014Koglin N., Zeh A., Cabral A.R., Gomes A.A.S., Corrêa Neto A.V., Brunetto W.J., Galbiatti H. 2014. Depositional age and sediment source of the auriferous Moeda Formation, Quadrilátero Ferrífero of Minas Gerais, Brazil: New constraints from U-Pb-Hf isotopes in zircon and xenotime. Precambrian Research, 255(Part 1):96-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2014.09.010

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Jordt-Evangelista et al. 2015Jordt-Evangelista H., Alvarenga J.P.M., Lana C. 2015. Petrography and geochronology of the Furquim Quartzite, an eastern extension of the Itacolomi Group (Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais). Revista Escola de Minas, 68(4):393-399. https://doi.org/10.1590/0370-44672015680054

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/...

, Nunes 2016Nunes F.S. 2016. Contribuição à estratigrafia e geocronologia U-Pb de zircões detríticos da Formação Moeda (Grupo Caraça, Supergrupo Minas) na Serra do Caraça, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais. Master of Science Dissertation, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto., Dopico et al. 2017Dopico C.I.M., Lana C., Moreira H.S., Cassino L.F., Alkmim F.F. 2017. U-Pb ages and Hf-isotope data of detrital zircons from the late Neoarchean-Paleoproterozoic Minas Basin, SE Brazil. Precambrian Research, 291:143-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2017.01.026

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Dutra 2017Dutra L.F. 2017. Caracterização geocronológica U-Th-Pb de zircões detríticos na porção nordeste do sinclinal Gandarela - implicações para evolução sedimentar e geotectônica do Quadrilátero Ferrífero. Dissertation, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, 100 p., Duque 2018Duque T.R.F. 2018. O Grupo Itacolomi em sua área tipo: estratigrafia, estrutura e significado tectônico. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto., Dutra et al. 2019Dutra L.F., Martins M., Lana C. 2019. Sedimentary and U-Pb detrital zircons provenance of the Paleoproterozoic Piracicaba and Sabará groups, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Southern São Francisco craton, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Geology, 49(2):e20180095. https://doi.org/10.1590/2317-4889201920180095

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/...

), in order to comprehend the provenance differences in the many geodynamic stages of the Minas-Itacolomi basins. In summary, this article presents, for the first time in the geological studies of the QF, a complete logging and description of sedimentary facies, depositional systems, and sequences (under the sequence stratigraphy approach), together with an U-Pb detrital zircon geochronological data compilation for provenance studies of the Minas-Itacolomi Palaeoproterozoic basins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The first stage of this article’s workflow was the bibliographic research, aiming to collect both historical and recent Minas Supergroup sedimentology works. Afterwards, several field trips to the QF were carried out, with the purpose of profiling its upper units through facies recognition and samples collection (for macroscopic and transmitted light microscopy petrographic descriptions). In this stage of the workflow, special attention by the authors was required, in order to recognise and to distinguish in the field primary sedimentary structures from tectonic structures, such as folds, cleavages, lineations, and other tectonic driven rock fabrics. The next stage of the workflow was the second bibliographic research, now focused on both the compilation of U-Pb zircon age data for the Minas-Itacolomi stratigraphic units and the Minas Basin geodynamic evolution. After all of the previous steps were concluded, the sequence stratigraphy principles (Catuneanu et al. 2005Catuneanu O., Martins-Neto M.A., Eriksson P.G. 2005. Precambrian sequence stratigraphy. Sedimentary Geology, 176(1-2):67-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2004.12.009

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Catuneanu 2006Catuneanu O. 2006. Principles of sequence stratigraphy. Elsevier, 376 p.) could be applied to the Minas-Itacolomi meta-sedimentary units, and the results were hereby presented.

The building block of sequence stratigraphy is the facies concept, which is defined as a particular combination of lithology, sedimentary structures, geometry, and textural attributes that allows to classify different sedimentary rock bodies. Therefore, facies is a product of sedimentary processes that exist in a specific depositional palaeoenvironment. Another important concept is the Walther’s Law: the vertical shifts of facies reflect corresponding lateral shifts of facies as well. Based on this principle, the facies association (i.e., groups of facies genetically related to one another and which have some environmental significance) is a critical element for the interpretation of palaeo-depositional systems (Dalrymple 2010Dalrymple R.W. 2010. Interpreting sedimentary successions: facies, facies analysis and facies models. In: James N.P. and Dalrimple R.W. (eds.). Facies Models 4. Geotext 6, Canadian Sedimentology, p. 3-18.).

The lateral succession of the depositional systems deposited at the same time window, is the very definition of system tracts, the second-to-last sequence stratigraphic unit, also known as the association between contemporary depositional systems. At this level, the eustasy plays a major key role in a sequence stratigraphic framework, as it determines the formation of packages of strata with specific stacking patterns, as well as of sequence stratigraphic surfaces, such as unconfomities and correlative conformities. Finally, those surfaces, made by contemporary or genetically related strata, are the ones that mark the limits of the sequences, the ultimate chronostratigraphic unit.

According to Catuneanu et al. (2011Catuneanu O., Galloway W.E., Kendall C.G.St.C., Miall A.D., Posamentier H.W., Strasser A., Tucker M.E. 2011. Sequence stratigraphy: methodology and nomenclature. Newsletters on Stratigraphy, 44(3):173-245. https://doi.org/10.1127/0078-0421/2011/0011

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1127/...

), the stacking patterns of the strata form geometrical trends that include upstepping, forestepping, backstepping, and downstepping. These geometrical trends mark the three types of shoreline shift: forced regression (FR) (forestepping and downstepping at the shoreline), normal regression (NR) (forestepping and upstepping at the shoreline), and transgression (backstepping at the shoreline).

During an FR, a falling stage systems tract (FSST) takes place. During an NR, two system tracts are possible, depending on the base level at that time: if the sea level was originally falling, caused by a previous FR, then the lowstand system tract (LST) takes place; otherwise (if the sea level was high at that time), the highstand system tract (HST) occurs. In between those NR system tracts, when the base level is rising, i.e., during a transgression (T), the transgressive system tract (TST) is the one in place (Catuneanu et al. 2005Catuneanu O., Martins-Neto M.A., Eriksson P.G. 2005. Precambrian sequence stratigraphy. Sedimentary Geology, 176(1-2):67-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2004.12.009

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Catuneanu 2006Catuneanu O. 2006. Principles of sequence stratigraphy. Elsevier, 376 p., Catuneanu et al. 2011Catuneanu O., Galloway W.E., Kendall C.G.St.C., Miall A.D., Posamentier H.W., Strasser A., Tucker M.E. 2011. Sequence stratigraphy: methodology and nomenclature. Newsletters on Stratigraphy, 44(3):173-245. https://doi.org/10.1127/0078-0421/2011/0011

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1127/...

).

For the provenance studies, palaeocurrent data are of great importance and can be obtained through many field-related techniques: the most straightforward is the direct measurements with the compass in the field, mainly from cross-beds. Sedimentary provenance can also be interpreted from analytical methods, such as from U-Pb geochronological data (Cawood et al. 2003Cawood P.A., Nemchin A.A., Freeman M., Sircombe K.N. 2003. Linking source and sedimentary basin: detrital zircon record of sediment flux along a modern river system and implications for provenance studies. Earth Planet Science Letters, 210(1-2):259-268. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00122-5

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Cawood et al. 2012Cawood P.A., Hawkesworth C.J., Dhuime B. 2012. Detrital zircon record and tectonic setting. Geology, 40(10):875-878. https://doi.org/10.1130/G32945.1

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1130/...

): through the interpretation of the zircon ages frequency distribution and testing for multi-modality (i.e., if the rock has derived from more than one source), one can have information of provenance if nearby possible sources have distinct ages. Another geochronological dating method (e.g., Ar-Ar, Sm-Nd, and Re-Os of different minerals) is not recommended for this type of study, as zircons are more resistant to weathering and provide a well-constrained U-Pb isotopic clock, even if found within sedimentary rocks that underwent a multi-event geological history. Hence, a detrital zircon U-Pb database was assembled for this work in order to validate the interpretations within, based on many previous works in the literature. The statistics for the geochronology database was calculated using either the Java-based DensityPlotter software (Vermeesch 2012Vermeesch P. 2012. On the visualisation of detrital age distributions. Chemical Geology, 312-313:190-194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2012.04.021

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

) or the software package within the statistical programming environment R, called Provenance (Vermeesch et al. 2016Vermeesch P., Resentini A., Garzanti E. 2016. An R package for statistical provenance analysis. Sedimentary Geology, 336, 14-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2016.01.009

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

).

GEOLOGICAL SETTING

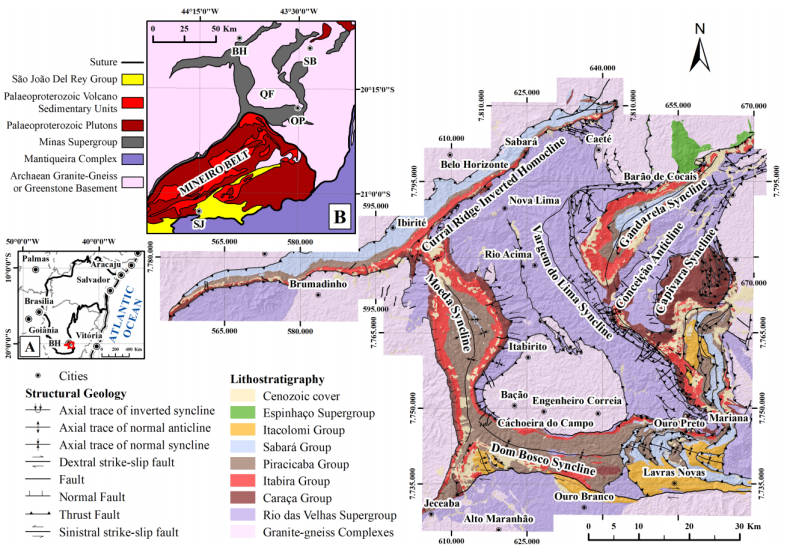

Located in the south-eastern region of the São Francisco Craton, the IQ is a metallogenic province of nearly 7,000 km2 (Figure 1). The QF is composed of archaean and proterozoic geological units. The Archaean basement is made of tonalitic granite-gneiss complexes, followed by the Rio das Velhas Supergroup, and overlain by the Proterozoic Minas Supergroup and the Itacolomi Group. All of the aforementioned units have undergone at least two tectonic/metamorphic events (the Transamazonian - also known as Minas Accretionary Orogeny or Palaeoproterozoic Orogeny - and the Brasiliano Orogenies), responsible for their complex deformation and metamorphic evolution.

Geological map of the Iron Quadrangle, with São Francisco Craton location (A) and Mineiro Belt (B).

The Rio das Velhas Supergroup is a greenstone belt divided into the Nova Lima and Maquiné groups (from base to top), and they have an estimated thickness of 4 and 1.6 km, respectively. The Nova Lima Group hosts the largest orogenic gold deposits that made the QF famous for its world-class deposits, whose mineralisation is sulphide related, and can be a function of either hydrothermal alteration with high structural control (as most orogenic gold deposits are) or stratabound nature mineralisation, such as volcanogenic massive sulphides (Ladeira, 1980Ladeira E.A. 1980. Metallogenesis of gold at the Morro Velho Mine and in the Nova Lima District, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Ph.D. thesis, University of Western Ontario, Ontario, 272 p., 1988Ladeira E.A. 1988. Metalogenia dos depóstis de ouro do Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais. In: Schobbenhaus C. and Coelho C.E.S. (Coords.). Principais depósitos minerais do Brasil. Metais básicos não-ferrosos, ouro e alumínio. Brasília: DNPM, p. 301-375., Lobato et al. 2001Lobato L.M., Rodrigues L.C.R., Vieira F.W.V. 2001. Brazil’s premier gold province. Part II: geology and genesis of gold deposits in the Archaean Rio das Velhas greenstone belt, Quadrilátero Ferrífero. Mineralium Deposita, 36(3-4):249-277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001260100180

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/...

, Lobato et al. 2016Lobato L.M., Costa M.A., Hagemann S.G., Martins R. 2016. Ouro no Brasil: principais depósitos, produção e perspectivas. In: Melfi A.J., Misi A., Campos D.A., Cordani U.G. (eds.). Recursos Minerais no Brasil, problemas e desafios. Rio de Janeiro: Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 420 p., Lobato and Costa 2018Lobato L.M., Costa M.A. 2018. Recursos minerais de Minas Gerais - ouro. In: Pedrosa-Soares A.C., Voll E., Cunha E.C. (coords.). Recursos Minerais de Minas Gerais On Line: Síntese do conhecimento sobre as riquezas minerais, história geológica, meio ambiente e mineração de Minas Gerais. Belo Horizonte: Companhia de Desenvolvimento de Minas Gerais (CODEMGE).).

This greenstone belt supergroup is composed mainly of mafic, ultramafic, chemical volcano-sedimentary rocks, volcanoclastic (mainly greywackes) rocks, and sandstones formed in episodic (cycles of) sedimentation. They record a submarine fan system transitioning to continental sedimentation, with intense island arc volcanism (Noce et al. 1992Noce C.M., Pinheiro S.O., Ladeira E.A., Franca C.R., Kattah S. 1992. A sequência vulcanossedimentar do Grupo Nova Lima na região de Piedade do Paraopeba, borda oeste do Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais. Revista Brasileira de Geociências, 22(2):175-183., Baltazar and Zucchetti 2007Baltazar O.F., Zucchetti M. 2007. Lithofacies associations and structural evolution of the Archean Rio das Velhas greenstone belt, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil: A review of the regional setting of gold deposits. Ore Geology Reviews, 32(3-4):471-499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2005.03.021

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Angeli 2015Angeli G. 2015. Arcabouço estrutural e contribuição à estratigrafia do Grupo Maquiné, Quadrilátero Ferrífero - Minas Gerais. Master of Science Dissertation, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto.).

The Minas Supergroup comprises the Caraça, Itabira, Piracicaba, and Sabará groups (base to top) that record a sedimentation from ca. 2580 to ca. 2050 Ma (Renger et al. 1994Renger F.E., Noce C.M., Romano A.W., Machado N. 1994. Evolução sedimentar do Supergrupo Minas: 500 Ma de registro geológico no Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais, Brasil. Geonomos, 2(1):1-11. https://doi.org/10.18285/geonomos.v2i1.227

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18285...

, Machado et al. 1996Machado N., Schrank A., Noce C.M., Gauthier G. 1996. Ages of detrital zircon from Archean-Paleoproterozoic sequences: Implications for Greenstone Belt setting and evolution of a Transamazonian foreland basin in Quadrilátero Ferrífero, southeast Brazil. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 141(1-4):259-276. https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-821X(96)00054-4

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Noce 2000Noce C.M. 2000. Geochronology of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero: a review. Geonomos, 8(1):15-23. https://doi.org/10.18285/geonomos.v8i1.144

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18285...

, Hartmann et al. 2006Hartmann L.A., Endo I., Suita M.T.F., Santos J.O.S., Frantz J.C., Carneiro M.A., McNaughton N.J., Barley M.E. 2006. Provenance and age delimitation of Quadrilátero Ferrífero sandstones based on zircon U-Pb isotopes. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 20(4):273-285., Farina et al. 2016Farina F., Albert C., Martínez Dopico C., Aguilar Gil C., Moreira H., Hippertt J.P., Cutts K., Alkmim F.F, Lana C. 2016. The Archean-Paleoproterozoic evolution of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero (Brazil): current models and open questions. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 68:4-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2015.10.015

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

). The basal Caraça Group is made of the Moeda and Batatal Formations, the first being mainly sandstones, with conglomerates and minor pelites, and the latter unit being pelitic (Dorr II 1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

, Alkmim and Martins-Neto 2012Alkmim F.F., Martins-Neto M.A. 2012. Proterozoic first-order sedimentary sequences of the São Francisco craton, eastern Brazil. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 33(1):127-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2011.08.011

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

).

The second group, Itabira, comprises the Cauê and Gandarela Formations, mainly made of itabirite (Lake Superior-type banded iron formations) and dolomite (dolostones), respectively (Dorr II 1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

, Rosière and Chemale Jr. 2000Rosière C.A., Chemale Jr. F. 2000. Itabiritos e minérios de ferro de alto teor do Quadrilátero Ferrífero - Uma visão geral e discussão. Geonomos, 8(2):27-43. https://doi.org/10.18285/geonomos.v8i2.155

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18285...

). The third group, Piracicaba is made of four formations: Cercadinho (mainly pelitic with some ferruginous coarse-grained sandstones), Fecho do Funil (also pelitic, but with subordinate dolomite lenses), Taboões (fine-grained sandstones), and Barreiro (pelitic) (Dorr II 1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

, Alkmim and Marshak 1998Alkmim F.F., Marshak S. 1998. Transamazonian Orogeny in the Southern São Francisco Craton Region, Minas Gerais, Brazil: evidence for Paleoproterozoic collision and collapse in the Quadrilátero Ferrífero. Precambrian Research, 90(1-2):29-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-9268(98)00032-1

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Farina et al. 2016Farina F., Albert C., Martínez Dopico C., Aguilar Gil C., Moreira H., Hippertt J.P., Cutts K., Alkmim F.F, Lana C. 2016. The Archean-Paleoproterozoic evolution of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero (Brazil): current models and open questions. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 68:4-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2015.10.015

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

).

The fourth group (Sabará) and the overlying Itacolomi Group are both syn-orogenic. Sabará is a flysch sequence (pelites, diamictites, wackes), while Itacolomi is the molasse sequence (sandstones and conglomerates) (Dorr II 1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

, Alkmim and Marshak 1998Alkmim F.F., Marshak S. 1998. Transamazonian Orogeny in the Southern São Francisco Craton Region, Minas Gerais, Brazil: evidence for Paleoproterozoic collision and collapse in the Quadrilátero Ferrífero. Precambrian Research, 90(1-2):29-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-9268(98)00032-1

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Almeida et al. 2005Almeida L.G., Castro P.T., Endo I., Fonseca M.A. 2005. O Grupo Sabará no Sinclinal Dom Bosco, Quadrilátero Ferrífero: uma revisão estratigráfica. Revista Brasileira de Geociências, 35(2):177-186., Alkmim and Martins-Neto 2012Alkmim F.F., Martins-Neto M.A. 2012. Proterozoic first-order sedimentary sequences of the São Francisco craton, eastern Brazil. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 33(1):127-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2011.08.011

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

). All of the IQ lithostratigraphic units are summarised in Table 1.

The main tectono-magmatic events in the IQ region are several Archaean magmatic pulses/events (Santa Bárbara, Rio das Velhas I and II, Mamona I and II) related to the basement of Minas Supergroup (i.e., granite-gneiss complexes and Rio das Velhas Supergroup); Minas Rift (taphrogenesis); Minas Accretionary Orogeny (formerly named Transamazonian) - related to the Sabará-Itacolomi sedimentation; Espinhaço Rift (minor mafic dyke swarms); and Brasiliano Orogeny (Araçuaí Belt) (Machado et al. 1992Machado N., Noce C.M., Ladeira E.A., Oliveira O.A.B. 1992. U-Pb geochronology of the Archean magmatism and Proterozoic metamorphism in the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, southern São Francisco Craton, Brazil. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 104(9):1221-1227. https://doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606(1992)104%3C1221:UPGOAM%3E2.3.CO;2

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1130/...

, Silva et al. 1995Silva A.M., Chemale Jr. F., Kuyumjian R.M., Heaman L. 1995. Mafic dike swarms of Quadrilátero Ferrífero and Southern Espinhaço, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Geociências, 25(2):124-137., Alkmim and Marshak 1998Alkmim F.F., Marshak S. 1998. Transamazonian Orogeny in the Southern São Francisco Craton Region, Minas Gerais, Brazil: evidence for Paleoproterozoic collision and collapse in the Quadrilátero Ferrífero. Precambrian Research, 90(1-2):29-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-9268(98)00032-1

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Lana et al. 2013Lana C., Alkmim F.F., Armstrong R., Scholz R., Romano R., Nalini Jr. H.A. 2013. The ancestry and magmatic evolution of Archean TTG rocks of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero province, southeast Brazil. Precambrian Research, 231:157-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2013.03.008

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Farina et al. 2015Farina F., Albert C., Lana C. 2015. The Neoarchean transition between medium and high-K granitoids: clues from the Southern São Francisco Craton (Brazil). Precambrian Research, 266:375-394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2015.05.038

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Teixeira et al. 2015Teixeira W., Ávila C.A., Dussin I.A., Corrêa Neto A.V., Bongiolo E.M., Santos J.O., Barbosa N.S. 2015. A juvenile accretion episode (2.35-2.32 Ga) in the Mineiro belt and its role to the Minas accretionary orogeny: Zircon U-Pb-Hf andgeochemical evidences. Precambrian Research, 256:148-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2014.11.009

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Farina et al. 2016Farina F., Albert C., Martínez Dopico C., Aguilar Gil C., Moreira H., Hippertt J.P., Cutts K., Alkmim F.F, Lana C. 2016. The Archean-Paleoproterozoic evolution of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero (Brazil): current models and open questions. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 68:4-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2015.10.015

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Albert 2017Albert C. 2017. Archean evolution of the southern São Francisco craton (SE Brazil). PhD Thesis, Escola de Minas, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto.). These events are summarised in Table 2.

SEDIMENTARY FACIES

The sedimentary facies for the Minas-Itacolomi basins are described below, in each correspondent stratigraphic group sub-chapter. The name of the sedimentary rock was mainly used, rather than its metamorphic name, as the majority of the rocks of the Minas Supergroup within the QF, they have low-grade metamorphism and their sedimentary structures are well preserved, especially when then are located far from the main high strain zones. Some facies were not identified in the authors’ fieldwork but are included in the text (with corresponding references), as they were previously described in the literature. The order in which the facies were catalogued in this work is according to their stratigraphic position, as observed in the field, from base to top. The lateral changes are frequent and are accounted for, since they represent the evolution of the depositional system.

Caraça Group

The seven sedimentary facies logged for the Moeda Formation, as well as the two facies of Batatal Formation are displayed in Table 3 and Figure 2. All of the authors’ field catalogued Moeda facies were also previously described by Dorr II (1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

), Villaça (1981Villaça J.N. 1981. Alguns aspectos sedimentares da Formação Moeda. Boletim, 2. Minas Gerais: Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia, Núcleo Minas Gerais.), and Madeira et al. (2018Madeira M.R., Martins M.S., Martins G.P., Alkmim F.F. 2018. Caracterização faciológica e evolução sedimentar da Formação Moeda (Supergrupo Minas) na porção noroeste do Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais. Geologia USP. Série Científica, 19(3):12-148. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9095.v19-148467

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11606...

), with the exception of a rare well-sorted fine-grained sandstone with hummocky cross-stratification identified by Canuto (2010Canuto J.R. 2010. Estratigrafia de seqüências em bacias sedimentares de diferentes idades e estilos tectônicos. Revista Brasileira de Geociências, 40(4):537-549.). Two additional Batatal Formation rare facies are fine sandstone (or chert), and jaspilite (or BIF oxide facies), according to Dorr II (1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

).

Caraça Group: (A) MOE1 facies - polymictic conglomerate - outcrop (X = 605,202; Y = 7,775,277; Z = 1,384 m); (B) MOE2 facies hand specimen - Au-bearing conglomerate with rounded detrital pyrites (Ouro Fino Mine - Jaguar Mining Inc.); (C) MOE4 facies - poorly sorted sandstone with trough cross-bedding - outcrop (X = 609,027.087; Y = 7,756,449.81; Z = 1,243.7 m); (D) MOE3 facies - poorly sorted sandstone with tabular cross-bedding and tangential foresets - outcrop (X = 604,540.709; Y = 7,779,506.869; Z = 1,343.9 m). Coordinates are in UTM and WGS84 datum.

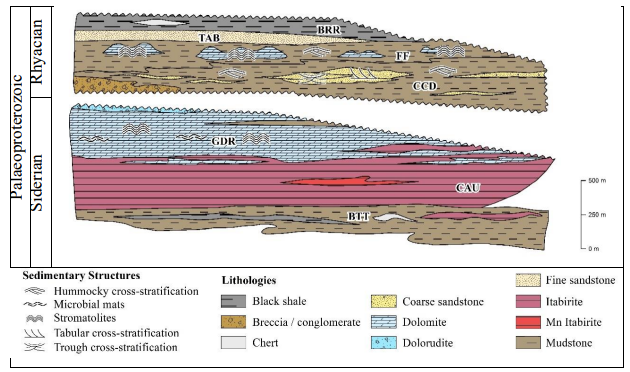

Itabira Group

The two sedimentary facies logged for the Cauê Formation, as well as the four facies of Gandarela Formation are displayed in Table 4 and Figure 3. Other Cauê Formation facies described in the literature are two types of itabirites (Mn-rich and amphibole-rich itabirites), and some other rare lithologies, such as volcaniclastic Mn-Fe-rich clay layers, carbonates, and mudstones (Dorr II 1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

, Suckau et al. 2005Suckau V.E., Suita M.T.F., Zapparolli A.C., Spier C.A., Ribeiro D.T. 2005. Transitional pyroclastic, volcanic-exhalative rocks to iron ores in the Cauê Formation, Tamanduá and Capitão do Mato Mines: an overview of metallogenetic and tectonic aspects. III Simpósio do Cráton de São Francisco. Anais... CBPM/UFBA/SBG, Salvador, p. 343-346., Cabral et al. 2012Cabral A.R., Zeh A., Koglin N., Seabra Gomes Jr. A.A., Viana D.J., Lehmann B. 2012. Dating the Itabira iron formation, Quadrilátero Ferrífero of Minas Gerais, Brazil, at 2.65 Ga: depositional U-Pb age of zircon from a metavolcanic layer. Precambrian Research, 204-205:40-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2012.02.006

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

). For the Gandarela Formation, the two other sedimentary facies also described in the literature are some volcanic layers (greenschist made of up to 80% chlorite, and minor quartz, biotite, magnetite), and stromatolitic grey limestone (Dorr II 1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

, Souza and Müller 1984Souza P.C., Müller G. 1984. Primeiras estruturas algais comprovadas na Formação Gandarela, Quadrilátero Ferrífero. Revista da Escola de Minas, 37(2):13-21.). The depositional systems for these facies are shallow subtidal to intertidal environments for the carbonate and pelitic lithologies, Lake Superior-type sedimentation (continental shelf) for the itabirites, and volcanogenic for the greenschists and volcaniclastic layers.

Itabira Group: (A) CAU1 facies - itabirite (X = 638,416.18; Y = 7,807,618.25; Z = 1,713 m); (B) GDR1 and GDR3 facies - dolomite and dolomitic mudstone (X = 643,411.603; Y = 7,746,329.701; Z = 1,081.6 m); (C) GDR1 facies - iron-rich dolomite (X = 638,900.029; Y = 7,781,831.391; Z = 1,383.2 m); (D) GDR2 facies - microbial mats dolomite hand specimen with well-preserved domal and laterally linked hemispheroids stromatolites and oncolites (X = 638,928.07; Y = 7,781,028.66; Z = 1,270 m). Coordinates are in UTM and WGS84 datum.

Piracicaba Group

The six sedimentary facies logged for the Cercadinho Formation, the five facies of Fecho do Funil Formation, the two facies of Taboões Formation, and the three facies of Barreiro Formation are displayed in Table 5 and Figure 4. Dorr II (1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

) also describes two rare sedimentary facies in the Cercadinho Formation: a basal pebble conglomerate (pebbles of itabirite, quartz, and quartzite), and dolomite lenses in the top of the unit. This work’s Piracicaba-logged facies are conformable with the literature (Dorr II 1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

, Dardenne and Campos Neto 1975Dardenne M.A., Campos Neto M.C. 1975. Estromatólitos colunares na série Minas (MG). Revista Brasileira de Geociências, 5(2):99-105., Cassedanne and Cassedanne 1976Cassedanne J., Cassedanne J. 1976. Les stromatolites columnaires de la carrière du Cumbe (Série Minas - Brèsil). Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, S7-XVIII (4):959-965. https://doi.org/10.2113/gssgfbull.S7-XVIII.4.959

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2113/...

, Garcia et al. 1988Garcia A.J.V., Fonseca M.A., Bernardi A.V., Januzzi A. 1988. Contribuição ao reconhecimento dos paleoambientes deposicionais do Grupo Piracicaba na região de Dom Bosco, SW de Ouro Preto, Quadrilátero Ferréfero. Acta Geologica Leopoldensia, 27:83-108., Kuchenbecker et al. 2015Kuchenbecker M., Fantinel L.M., Fairchild T.R., Rohn R. 2015. Microbialitos da Formação Fecho do Funil (Paleoproterozoico) na Pedreira Cumbi, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais. In: Fairchild T.R., Rohn R., Dias-Brito D.. Microbialitos do Brasil do Pré-Cambriano ao Recente. Um Atlas. UNESPetro, Obra 2, Capítulo 5.).

Piracicaba Group: (A) CCD1, CCD4, and CCD5 facies - carbonaceous shale, ferruginous sandstone, and quartz sandstone (X = 640,038.668; Y = 7,741,900.304; Z = 1,274.5 m); (B) CCD6 facies - rithmite with hummocky cross-stratification (X = 611,172.722; Y = 7,792,421.984; Z = 1,107.6 m); (C and D) FF2 facies hand specimen - stromatolite (X = 636,590.210; Y = 7,742,150.558; Z = 1,103.0 m); (E) FF4 facies - rhythmite with hummocky cross-stratification (X = 612,218.012; Y = 7,768,982.647; Z = 1,245.2 m); (F) FF2 and FF1 facies - dolomite lens within mudstones (X = 645,411.412; Y = 7,745,965.808; Z = 1,145.5 m). Coordinates are in UTM and WGS84 datum.

Sabará Group

The five sedimentary facies logged for the Sabará Group are displayed in Table 6 and Figure 5. All of the authors’ field catalogued Sabará Group facies were also previously described by Dorr II (1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

) and Reis et al. (2002Reis L.A., Neto M.A.M., Gomes N.S., Endo I., Evangelista H.J. 2002. A Bacia de Antepaís Paleoproterozóica Sabará, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais. Revista Brasileira de Geociências, 32(1):27-42.).

Sabará Group: (A) SAB5 facies - very crenulated rhythmite, or distal turbidite (X = 655,490.229; Y = 7,741,168.287; Z = 1,365.5 m); (B) SAB3 and SAB5 facies - laminated mudstone and rhythmite, or distal turbidites (X = 655,498.996; Y = 7,741,106.157; Z = 1,384.3 m); (C) SAB4 (sandstone / wacke) and SAB2 (diamictite) facies contact (X = 655,498.996; Y = 7,741,106.157; Z = 1,384.3 m); (D) SAB1 gravelly conglomerate with graded bedding, deposited by turbidity currents (X = 614,564.714; Y = 7,767,873.112; Z = 1,241.1 m). Coordinates are in UTM and WGS84 datum.

Itacolomi Group

The six sedimentary facies logged for the Itacolomi Group are displayed in Table 7 and Figure 6. This paper’s Itacolomi Group logged facies are conformable with the ones previously described by Alkmim (1987Alkmim F.F. 1987. Modelo deposicional para a sequência de metassedimentos da Serra de Ouro Branco, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais. In: Simpósio sobre Sistemas Deposicionais no Pré-Cambriano, Ouro Preto. Anais... Boletim, 6. Minas Gerais: Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia, Núcleo Minas Gerais.), Duque (2018Duque T.R.F. 2018. O Grupo Itacolomi em sua área tipo: estratigrafia, estrutura e significado tectônico. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto.), and Duque et al. (2020Duque T.R.F., Alkmim F.F., Lana C.C. 2020. Grãos detríticos de zircão do Grupo Itacolomi em sua área tipo, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais: idades, proveniência e significado tectônico. Geologia USP. Série Científica, 20(1):101-123. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9095.v20-151397

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11606...

), but the first author also describes an extra sandstone facies (with ripple marks and interbedded mudstone/siltstone flaser beds) of a tidal flat depositional environment in the Serra de Ouro Branco locality.

Itacolomi Group: (A) ITA3 facies - gravelly sandstone with planar stratification (X = 657,277.655; Y = 7,739,784.725; Z = 1,586.1 m); (B) ITA5 facies - gravelly sandstone with trough cross-bedding (X = 641,790.022; Y = 7,731,895.969; Z = 1,322.7 m). Coordinates are in UTM and WGS84 datum.

FROM SEDIMENTARY FACIES TO DEPOSITIONAL SYSTEMS

At the base of the Caraça Group, the Moeda Formation contains layers and lenses of quartz arenites and quartz pebble-cobble conglomerates. The MOE1 and MOE2 facies (polymictic and oligomictic conglomerates) are found with erosional contact with the basement and record an important feature of the atmospheric conditions at the early stages of the Minas basins: detrital pyrite is the evidence for the then reducing atmospheric conditions; otherwise, it would have been oxidised to iron oxides and iron hydroxides. This facies, deposited by debris flow in an alluvial fan (Miall 2010Miall A.D. 2010. Alluvial deposits. In: James N.P., Dalrymple R.W. (eds.). Facies Models 4. Eds: Geotext 6. Canadian Sedimentology, p. 105-137.), also has a certain degree of similarity with the Witwatersrand Au-U-bearing conglomerates (Villaça 1981Villaça J.N. 1981. Alguns aspectos sedimentares da Formação Moeda. Boletim, 2. Minas Gerais: Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia, Núcleo Minas Gerais., Minter et al. 1990Minter W.E.L., Renger F.E., Siegers A. 1990. Early proterozoic gold placers of the moeda formation within the gandarela syncline, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Economic Geology, 85(5):943-951. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsecongeo.85.5.943

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2113/...

, Pires 2005Pires P.F.R. 2005. Gênese dos depósitos auríferos em metaconglomerados da Formação Moeda, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, MG: O papel do metamorfismo e associação com a matéria carbonosa. Tese de doutorado, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas.).

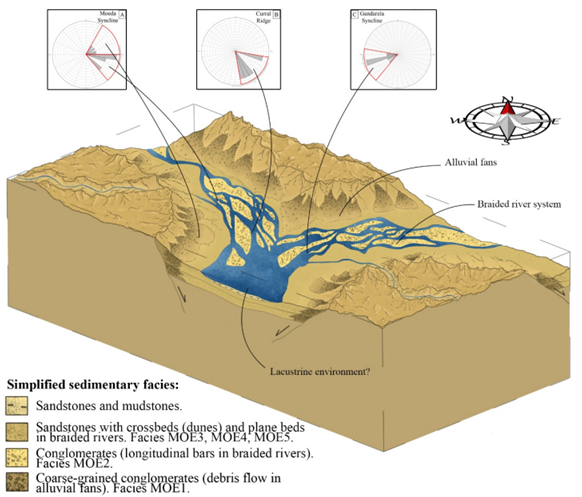

The MOE2, MOE3, MOE4, and MOE5 facies (conglomerates and poorly sorted sandstones) comprise this unit’s most abundant set of facies (both in thickness and lateral continuity). MOE2 (oligomictic conglomerate) is made of gravels deposited in longitudinal bars of braided rivers, whilst MOE3 and MOE4 (poorly sorted sandstones with trough or tabular bedding) are deposited by subaqueous dunes (sinuous and straight crested) in braided river environments. The planar-bedded MOE5 sandstone represents the upper flow regime in this fluvial system.

The less common MOE6 and MOE7 facies, due to the fact that they are laminated siltstone (with minor fine sand inputs) and laminated mudstone, respectively, represent finer sedimentation (clays and silts settling) of river streams/abandoned channels and/or lake environments. Overall, the Moeda Formation is nearly 300 m thick and comprehends both alluvial fan and braided fluvial sedimentation (Miall 1978Miall A.D. 1978. Lithofacies types and vertical profile models in braided river deposits: a summary. In: Miall A.D. (ed.). Fluvial Sedimentology, Memoir 5. Calgary: Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists, p. 597-604., 2010Miall A.D. 2010. Alluvial deposits. In: James N.P., Dalrymple R.W. (eds.). Facies Models 4. Eds: Geotext 6. Canadian Sedimentology, p. 105-137., Villaça 1981Villaça J.N. 1981. Alguns aspectos sedimentares da Formação Moeda. Boletim, 2. Minas Gerais: Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia, Núcleo Minas Gerais., Minter et al. 1990Minter W.E.L., Renger F.E., Siegers A. 1990. Early proterozoic gold placers of the moeda formation within the gandarela syncline, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Economic Geology, 85(5):943-951. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsecongeo.85.5.943

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2113/...

, Renger et al. 1994Renger F.E., Noce C.M., Romano A.W., Machado N. 1994. Evolução sedimentar do Supergrupo Minas: 500 Ma de registro geológico no Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais, Brasil. Geonomos, 2(1):1-11. https://doi.org/10.18285/geonomos.v2i1.227

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18285...

, Madeira 2018Madeira M.R. 2018. Evolução sedimentar e história deformacional da Formação Moeda ao longo da junção entre o Sinclinal da Moeda e o Homoclinal da Serra do Curral, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, MG. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto.), as depicted in Figure 7. Fine-grained, well-sorted sandstones and mudstones that outcrop in the south-east of IQ most likely represent lacustrine sedimentation.

Palaeogeography of the rift stage of the Minas Basin: Moeda Formation. Compass and rose diagrams indicate sediment flow direction based on current day geographic coordinates (A is from Moeda Syncline; B is from Curral Ridge; C is from Gandarela Syncline). Palaeocurrent data are from the authors’ fieldworks, interpretations of facies lateral variations, and Villaça (1981Villaça J.N. 1981. Alguns aspectos sedimentares da Formação Moeda. Boletim, 2. Minas Gerais: Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia, Núcleo Minas Gerais.).

Each palaeocurrent data subset displayed in Figure 7 (from the authors’ fieldworks, interpretations of facies lateral variations, and Villaça 1981Villaça J.N. 1981. Alguns aspectos sedimentares da Formação Moeda. Boletim, 2. Minas Gerais: Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia, Núcleo Minas Gerais.) was collected in different geological domains of QF (i.e., Moeda Syncline, Curral Ridge, and Gandarela Syncline), and they were grouped accordingly. Overall, there were three main directions of sediment flow, from the NE, SE, and WSW.

The conformably and, locally, gradationally overlying Batatal Formation contains sericitic and graphitic mudstones, cherts, and banded iron formations. The BTT1 and BTT2 are alternated laminated mudstones facies, varying only in accessory mineral contents: organic content (carbonaceous mudstone) and its absence (sericitic mudstone). Both facies comprise a nearly 200 m thick sequence with great lateral continuity of marine sedimentation with sharp or gradational contact with the Moeda facies set. The less common BTT3 and BTT4 facies, as originally described by Dorr II (1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

) made of rare quartzite/metachert and itabirites represent small pulses of chemical sedimentation in (as stated before) marine environments, prior to the onset of the environmental conditions responsible for the Itabira Group sedimentation. The Caraça Group thus records a rift to passive margin shift in the Minas Basin tectonic regime, being the Moeda Formation, the continental rift sedimentation in gradational contact with the Batatal marine transgression.

The Itabira Group contains the Cauê iron-rich Formation and the overlying Gandarela Formation. The mudstones in the upper few metres of the Batatal Formation are Fe-rich and they grade upwards into the overlying CAU1 facies, which is composed of banded iron formations (itabirite). This facies is parallel bedded and mostly homogeneous, which would imply shallow marine (passive margin) conditions for the iron oxides to precipitate and form such a rock fabric. Since it is a Lake Superior-type BIF (Olivo et al. 1995Olivo G.R., Gauthier M., Bardoux M., Leão de Sá E., Fonseca J.T.F., Santana F.C. 1995. Palladium-bearing gold deposit hosted by Proterozoic Lake Superior - type iron formation at the Cauê Iron mine, Itabira District, Southern São Francisco Craton, Brazil: geologic and structural control. Economic Geology, 90(1):118-134. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsecongeo.90.1.118

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2113/...

), its depositional system is interpreted as a continental shelf. This facies, together with the CAU2, mark the oxyatmoversion (great oxidation event, also known as “GOE”) in the Minas Basin, within a 500-m thick iron-rich succession, as the U-Pb zircon age of a metavolcanic layer within the Cauê BIF (Cabral et al. 2012Cabral A.R., Zeh A., Koglin N., Seabra Gomes Jr. A.A., Viana D.J., Lehmann B. 2012. Dating the Itabira iron formation, Quadrilátero Ferrífero of Minas Gerais, Brazil, at 2.65 Ga: depositional U-Pb age of zircon from a metavolcanic layer. Precambrian Research, 204-205:40-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2012.02.006

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

) also matches the age of the GOE (Olejarz et al. 2021Olejarz J., Iwasa Y., Knoll A.H., Nowak M.A. 2021. The Great Oxygenation Event as a consequence of ecological dynamics modulated by planetary change. Nature Communications, 12:3985. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23286-7

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/...

). The rare volcaniclastic facies (Dorr II 1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

, Suckau et al. 2005Suckau V.E., Suita M.T.F., Zapparolli A.C., Spier C.A., Ribeiro D.T. 2005. Transitional pyroclastic, volcanic-exhalative rocks to iron ores in the Cauê Formation, Tamanduá and Capitão do Mato Mines: an overview of metallogenetic and tectonic aspects. III Simpósio do Cráton de São Francisco. Anais... CBPM/UFBA/SBG, Salvador, p. 343-346., Cabral et al. 2012Cabral A.R., Zeh A., Koglin N., Seabra Gomes Jr. A.A., Viana D.J., Lehmann B. 2012. Dating the Itabira iron formation, Quadrilátero Ferrífero of Minas Gerais, Brazil, at 2.65 Ga: depositional U-Pb age of zircon from a metavolcanic layer. Precambrian Research, 204-205:40-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2012.02.006

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

) suggests a small volcanism-related input to this marine sedimentation. Differences in the HREE signatures of itabirites suggest that dolomitic itabirites precipitated in shallower waters, receiving sediments from the continent, whilst quartz itabirite precipitated in deeper waters, with hydrothermal contribution (Spier et al. 2007Spier C.A., Oliveira S.M.B., Sial A.N., Rios F.J. 2007. Geochemistry and genesis of the banded iron formations of the Cauê Formation, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Precambrian Research, 152(3-4):170-206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2006.10.003

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

).

The Gandarela Formation has gradational contact with the Cauê Formation and includes dolomites, limestones, dolomitic mudstones (GDR3), dolomitic iron formations (GDR1), and mudstones (Dorr II 1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

). Carbonates (GDR2) in the middle part of the Gandarela Formation contain well-preserved domal and laterally linked hemispheroids stromatolites and oncolites (Souza and Müller 1984Souza P.C., Müller G. 1984. Primeiras estruturas algais comprovadas na Formação Gandarela, Quadrilátero Ferrífero. Revista da Escola de Minas, 37(2):13-21.), indicating deposition in high-energy intertidal to shallow subtidal environments (Bekker et al. 2003Bekker A., Sial A., Karhu J., Ferreira V., Noce C., Kaufman A., Romano A., Pimentel M. 2003. Chemostratigraphy of Carbonates from the Minas Supergroup, Quadrilatero Ferryifero (Iron Quadrangle), Brazil: A Stratigraphic Record of Early Proterozoic Atmospheric, Biogeochemical and Climactic Change. American Journal of Science, 303(10):865-904. https://doi.org/10.2475/ajs.303.10.865

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2475/...

). The GDR4 (dolorudite) is an intraformational reworking of the carbonates by waves or tides. All of the Gandarela Formation facies show a shallow marine depositional system (carbonate precipitation related). Similarly to the Cauê Formation, the Gandarela Formation also has volcanogenic facies (Dorr II 1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

). In total, the estimated thickness for the Gandarela formation is 500 m.

The Cercadinho Formation has six facies and it lies at an erosional contact with the Itabira Group (Rossignol et al. 2020Rossignol C., Lana C., Alkmim F. 2020. Geodynamic evolution of the Minas Basin, southern São Francisco Craton (Brazil), during the early Paleoproterozoic: Climate or tectonic? Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 101:102628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2020.102628

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

). The basal pebble conglomerate facies (described by Dorr II 1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

) is found only at the Curral Ridge and is mainly a product of reworking of underlying units (pebbles of itabirites and sandstones). The Cercadinho main facies are the CCD1, CCD2, and CCD3 (carbonaceous, ferruginous, and chloritic shales, respectively). The CCD4 (rounded medium-grained ferruginous sandstone) is often found interbedded with the shales of CCD1, CCD2 or CCD3. In a similar geometry, the CCD5 (medium- to coarse-grained quartz sandstone) is found within the shales (in lenses), as well as the CCD6 facies (laminated rhythmite) does. The latter, found in the Curral Ridge, presents a hummocky cross-stratification, thus indicating a shallower marine environment to the NW of the QF with storm activity. A shallower marine sedimentation is also evidenced by the rare dolomite lenses facies (Dorr II 1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

). All of the six facies of this formation are approximately 500 m thick and are interpreted as a result of marine shelf bars (Garcia et al. 1988Garcia A.J.V., Fonseca M.A., Bernardi A.V., Januzzi A. 1988. Contribuição ao reconhecimento dos paleoambientes deposicionais do Grupo Piracicaba na região de Dom Bosco, SW de Ouro Preto, Quadrilátero Ferréfero. Acta Geologica Leopoldensia, 27:83-108.) or shelf sand bars sedimentation in the offshore-shoreface transition zone, with lenticular sandstones intercalated with mudstones. Mud and fine sand deposits intercalation or mud beds record several episodes of distal storm or post-storm events. The thin conglomerate may be due to the erosion, as a result of storm waves on the shelf or the influence of deltas with greater erosive power in the coastal environment of the continental shelf.

The FF1 facies is the most common in the Fecho do Funil Formation, composed of laminated dolomitic mudstone. It is often in sharp contact with white/dark grey stromatolitic dolomite in lenses of the FF2 facies. Less commonly, there are a few up to 40 cm beds of FF3 fine- to medium-grained sandstone with low angle tabular cross-bedding within the FF1 facies. To the top of the formation, there is a layer of FF4 facies (laminated rhythmite: alternating red silty sandstone and grey claystone), a few dozen metres thick, with a hummocky cross-stratification pattern, indicating storm activity in shallow marine context. Another common sedimentary facies of this unit is the FF5, made of thin beds of carbonaceous mudstones, preserved in reducing environments. Overall, the total thickness for Fecho do Funil Formation is estimated at approximately 300 m and its depositional system is interpreted as a coastal environment, subtidal, with carbonaceous and carbonatic pelites and microbial reefs (bioherms) made up by stromatolites that have a wide variety of morphologies (Dardenne and Campos Neto 1975Dardenne M.A., Campos Neto M.C. 1975. Estromatólitos colunares na série Minas (MG). Revista Brasileira de Geociências, 5(2):99-105.). It possibly had a low relief source area, with coastal sedimentation of carbonaceous and carbonatic pelites and bioherms in a shallow marine ramp. The whole formation likely represents a regressive cycle with the deeper water facies at the base (pelites) and upward shallowing (stromatolite dolomite lenses) trend towards the top (Bekker et al. 2003Bekker A., Sial A., Karhu J., Ferreira V., Noce C., Kaufman A., Romano A., Pimentel M. 2003. Chemostratigraphy of Carbonates from the Minas Supergroup, Quadrilatero Ferryifero (Iron Quadrangle), Brazil: A Stratigraphic Record of Early Proterozoic Atmospheric, Biogeochemical and Climactic Change. American Journal of Science, 303(10):865-904. https://doi.org/10.2475/ajs.303.10.865

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2475/...

).

The overlying Taboões Formation (maximum thickness of 120 m) presents the TAB1 facies and is made of fine-grained, very well-sorted, laminated quartz sandstone. The other sedimentary facies for this stratigraphic unit is the TAB2, which is also made of a fine-grained terrigenous rock: a rhythmite (alternating siltstone and fine sandstone layers). Both facies can be interpreted as a result of a delta depositional system. To the north, in Curral Ridge, the TAB1 sandstones outcrop, with thicknesses that range from 70 to 150 m, possibly representing delta front facies. In the central region of the QF (Moeda Syncline), the rhythmites and pelites (TAB2) are more representative, approximately 30 m thick, representing the prodelta facies.

The Barreiro Formation is a fairly homogeneous unit, concerning its constituting rock type, with a maximum thickness of 120 m and made of three alternating BRR1, BRR2, and BRR3 facies: pink mudstone, carbonaceous (grey) mudstone, and yellow rhythmite. The depositional systems interpreted for this unit are the continental shelf (below the wave base).

The depositional systems identified for the sedimentary facies from the Batatal Formation to the Barreiro Formation are all related to a passive margin tectonic regime, as depicted in Figure 8.

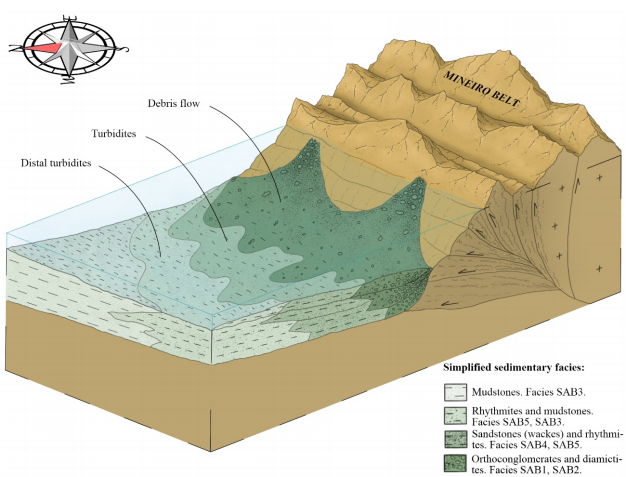

The overlying Sabará Group, approximately 3,500 m thick, has five facies: conglomerates (orthoconglomerate and diamictite), sandstones, laminated, and massive pelites. The SAB1 (conglomerate facies) overlies the Piracicaba Group with an erosional contact (unconformity) and was deposited by subaqueous debris flow. This facies often gradates towards the SAB2 facies, the diamictite, deposited also by the same sedimentary process (subaqueous debris flow). The SAB3, SAB4, and SAB5 facies were deposited by mass flow and turbidity currents of high and low density, thus representing proximal and distal turbidites. The debris flow facies are thicker at the base of the group, but they still exist in thinner beds (up to a few metres thick) towards the top. The most abundant facies is the SAB3, the laminated mudstone, deposited by distal turbidity currents, as the interbedded SAB5 (rhythmite, often with high carbonaceous content) facies also was. The SAB4 (wacke) facies was deposited by mass flow/high-density turbidity currents and, therefore, interpreted as a part of the proximal turbidites. All of the five facies make the submarine fan, with gravitational subaqueous debris flow and turbidite currents depositional system (Reis et al. 2002Reis L.A., Neto M.A.M., Gomes N.S., Endo I., Evangelista H.J. 2002. A Bacia de Antepaís Paleoproterozóica Sabará, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais. Revista Brasileira de Geociências, 32(1):27-42., Arnott 2010Arnott R.W. 2010. Deep-marine sediments and sedimentary systems. In: James N.P. and Dalrymple R.W. (eds.). Facies Models 4. Geotext 6. Canadian Sedimentology. 295-322 p.). Since it lies within a foreland basin (in the foredeep), close to a building orogen, the term flysch applies (as previously interpreted by Dorr II 1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

) (Figure 9).

Sabará Group foreland (flysch) sedimentation. São Francisco palaeo-craton lies to NW and orogenic belt to SE. Compass indicates sediment flow direction based on current day geographic coordinates.

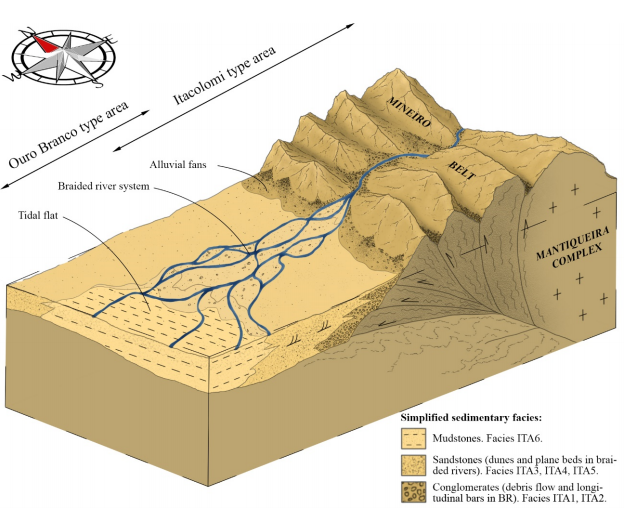

Finally, the Itacolomi Group (approximately 2,000 m thick) is made of six facies. The ITA1 and ITA2, made of orthoconglomerates most likely were made by proximal alluvial fans sedimentation and by gravel-filled longitudinal bars in braided rivers (Miall, 1978Miall A.D. 1978. Lithofacies types and vertical profile models in braided river deposits: a summary. In: Miall A.D. (ed.). Fluvial Sedimentology, Memoir 5. Calgary: Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists, p. 597-604., 2010Miall A.D. 2010. Alluvial deposits. In: James N.P., Dalrymple R.W. (eds.). Facies Models 4. Eds: Geotext 6. Canadian Sedimentology, p. 105-137.). The facies ITA3, ITA4, and ITA5, since they are made of gravelly sandstones, a poorly sorted sedimentary rock with both cross and planar bedding, the facies association allows the interpretation of medial to distal alluvial fans and/or braided stream channels sedimentation (upper flow regime for the planar beds, as well as lower flow regime for the subaqueous dunes and cross-beds). Within the Ouro Branco Ridge, two finer grained facies (one of which suggesting flaser beds, according to Alkmim 1987Alkmim F.F. 1987. Modelo deposicional para a sequência de metassedimentos da Serra de Ouro Branco, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais. In: Simpósio sobre Sistemas Deposicionais no Pré-Cambriano, Ouro Preto. Anais... Boletim, 6. Minas Gerais: Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia, Núcleo Minas Gerais.) were identified (ITA6 and ITA7) and are interpreted as the result of tidal flat sedimentation. In summary, this entire succession is related to alluvial and fluvial (braided stream channels) molasse, with subordinate tidal flat depositional systems (Figure 10).

Itacolomi Group foreland (molasse) sedimentation. Reverse faults represent the Mineiro Belt orogenesis. Compass indicates sediment flow direction based on current day geographic coordinates.

SYSTEM TRACTS AND SEQUENCES

The system tracts are defined as the lateral succession of the depositional systems deposited at the same time, which tend to form specific stratigraphic frameworks as the geological history evolves (Catuneanu et al. 2005Catuneanu O., Martins-Neto M.A., Eriksson P.G. 2005. Precambrian sequence stratigraphy. Sedimentary Geology, 176(1-2):67-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2004.12.009

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Catuneanu 2006Catuneanu O. 2006. Principles of sequence stratigraphy. Elsevier, 376 p.). Those frameworks are the stratigraphic surfaces themselves, made by contemporary or genetically related strata, and some of them mark the limits of the sequences, driven by both the sea-level change and sedimentation rates. The goal of this section is to provide an interpretation of the sequence stratigraphic framework of the Minas-Itacolomi Basins.

The Moeda Formation has many alluvial fans and high-energy braided river facies (Villaça 1981Villaça J.N. 1981. Alguns aspectos sedimentares da Formação Moeda. Boletim, 2. Minas Gerais: Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia, Núcleo Minas Gerais., Madeira et al. 2018Madeira M.R., Martins M.S., Martins G.P., Alkmim F.F. 2018. Caracterização faciológica e evolução sedimentar da Formação Moeda (Supergrupo Minas) na porção noroeste do Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais. Geologia USP. Série Científica, 19(3):12-148. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9095.v19-148467

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11606...

) (Figure 7). Fine-grained, well-sorted sandstones and mudstones that outcrop in the central and south-eastern areas of IQ are interpreted as a lacustrine environment (Madeira et al. 2018Madeira M.R., Martins M.S., Martins G.P., Alkmim F.F. 2018. Caracterização faciológica e evolução sedimentar da Formação Moeda (Supergrupo Minas) na porção noroeste do Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais. Geologia USP. Série Científica, 19(3):12-148. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9095.v19-148467

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11606...

). Normal faults are inferred, considering the occurrence of thick alluvial fans, and they represent the rift phase (with mechanic subsidence) of the Minas Basin geological evolution. This depositional context is considered LST, as continental sedimentation predominates within the basin at this time.

The Batatal Formation hosts pelitic facies, and locally, cherts, and banded iron formations. It comprises the beginning of a TST, as the sea level rises, leading the Minas Basin towards a marine platform development. This interpretation makes possible to classify the contact between Moeda and Batatal Formations as the maximum regressive surface (MRS) stratigraphic surface. Sediment input is lessened with the sea-level rise, allowing large-scale clay settling (and occasionally, chemical and organic matter precipitation/deposition) in the basin. This Formation has a gradational contact with the overlying Cauê Formation, which is mostly homogeneous, with thick itabirite beds and minor mudstones and carbonate-rich iron formations. Cauê Formation is the continuity of the TST, with further lower rates of terrigenous inputs and chemical precipitation dominance, where large amounts of Fe2+ ions were being oxidised to Fe3+. Hydrothermal submarine contribution was responsible for higher concentrations of Fe2+, as the geochemical studies of Spier et al. (2007Spier C.A., Oliveira S.M.B., Sial A.N., Rios F.J. 2007. Geochemistry and genesis of the banded iron formations of the Cauê Formation, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Precambrian Research, 152(3-4):170-206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2006.10.003

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

) suggest.

A maximum flooding surface (MFS) is inferred at the midportion of Cauê Formation, possibly where the clay/mud and the volcaniclastic beds lie (Dorr II 1969Dorr II J.V.N. 1969. Physiographic, stratigraphic and structural development of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Washington: USGS/DNPM. Professional Paper. 641(A):110 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp641A

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/...

, Suckau et al. 2005Suckau V.E., Suita M.T.F., Zapparolli A.C., Spier C.A., Ribeiro D.T. 2005. Transitional pyroclastic, volcanic-exhalative rocks to iron ores in the Cauê Formation, Tamanduá and Capitão do Mato Mines: an overview of metallogenetic and tectonic aspects. III Simpósio do Cráton de São Francisco. Anais... CBPM/UFBA/SBG, Salvador, p. 343-346., Cabral et al. 2012Cabral A.R., Zeh A., Koglin N., Seabra Gomes Jr. A.A., Viana D.J., Lehmann B. 2012. Dating the Itabira iron formation, Quadrilátero Ferrífero of Minas Gerais, Brazil, at 2.65 Ga: depositional U-Pb age of zircon from a metavolcanic layer. Precambrian Research, 204-205:40-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2012.02.006

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

), prior to the carbonate-rich iron formations and carbonate beds that represent the transition to Gandarela Formation. Above the MFS, there is a gradual increase of terrigenous input, shifting towards a progradational pattern, with the onset of a slow marine regression, and further shallowing of marine facies. This sedimentary setting comprises the HST, which takes place throughout the entire Gandarela Formation. This stratigraphic unit’s facies indicate the existence of both shallow water carbonates (stromatolites and oncolites, Souza and Müller 1984Souza P.C., Müller G. 1984. Primeiras estruturas algais comprovadas na Formação Gandarela, Quadrilátero Ferrífero. Revista da Escola de Minas, 37(2):13-21., Bekker et al. 2003Bekker A., Sial A., Karhu J., Ferreira V., Noce C., Kaufman A., Romano A., Pimentel M. 2003. Chemostratigraphy of Carbonates from the Minas Supergroup, Quadrilatero Ferryifero (Iron Quadrangle), Brazil: A Stratigraphic Record of Early Proterozoic Atmospheric, Biogeochemical and Climactic Change. American Journal of Science, 303(10):865-904. https://doi.org/10.2475/ajs.303.10.865

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2475/...

) and deep-water carbonates and pelites, thus making a palaeoproterozoic carbonate platform. The first depositional sequence (Sequence 1) of Minas Basin is made by all the four basal formations (i.e., Moeda, Batatal, Cauê, and Gandarela), and the three aforementioned system tracts (i.e., LST, TST, and HST).

Between the Itabira and Piracicaba Groups, there is an important discordance in the Minas Basin evolution, which probably represents a hiatus of ca. 60 Ma (Rossignol et al. 2020Rossignol C., Lana C., Alkmim F. 2020. Geodynamic evolution of the Minas Basin, southern São Francisco Craton (Brazil), during the early Paleoproterozoic: Climate or tectonic? Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 101:102628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2020.102628

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

). This event is still little understood, but can be explained by a sea-level fall and consequent erosion of Itabira Group, on the late stages of the HST. According to Rossignol et al. (2020Rossignol C., Lana C., Alkmim F. 2020. Geodynamic evolution of the Minas Basin, southern São Francisco Craton (Brazil), during the early Paleoproterozoic: Climate or tectonic? Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 101:102628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2020.102628

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

), the discordance is due to the onset of Mineiro Belt Palaeoproterozoic tectonics.

The Piracicaba Group’s basal Cercadinho Formation hosts sandstone lenses amidst mudstones, as platform sandbars in the marine environment. They are either amalgamated sandbars (shoreface) or isolated within the pelites of the platform (offshore). Such depositional environment belongs to a TST, with progressive supply reduction. At the base, it is possible to infer a transgressive ravinement surface (TRS), as the sea level rises. Towards the top, the Cercadinho Formation transitions to the Fecho do Funil Formation, with the reduction of sand lenses, and further onset of dolomitic lenses. An MFS can be inferred at the base of Fecho do Funil Formation prior to the carbonate lenses, where thick (sometimes discontinuous) carbonaceous mudstone beds lie. The upper Fecho do Funil Formation represents a shallowing HST that enabled stromatolitic dolomite lenses and fine-grained shoreface sandstones to be formed.

The Taboões Formation’s delta front and prodelta facies lie directly over the platform mudstones of Fecho do Funil, which imply an abrupt change in sediment input (progradation increases and the sea level is even lower, as shoreline moves basinward), characteristic of an LST. This geological contact can be interpreted as a correlative conformity (therefore, an interpreted discordance, since the system tracts shift from a Highstand to a Lowstand), which marks the end of the Sequence 2 (that started in the base of Piracicaba Group). Taboões and Barreiro’s contacts are sharp, and as Taboões thins out, Barreiro Formation sometimes overlies directly the Fecho do Funil Formation (another evidence for the correlative conformity interpretation). Barreiro’s carbonaceous mudstones and rhythmites are deposited onlapping the Minas Basin, at a TST, and the unit’s upper contact is as erosive one that ends the Sequence 3.

Sequences 4 and 5 (to be described next) are deposited in a foreland basin (Alkmim and Marshak 1998Alkmim F.F., Marshak S. 1998. Transamazonian Orogeny in the Southern São Francisco Craton Region, Minas Gerais, Brazil: evidence for Paleoproterozoic collision and collapse in the Quadrilátero Ferrífero. Precambrian Research, 90(1-2):29-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-9268(98)00032-1

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

, Reis et al. 2002Reis L.A., Neto M.A.M., Gomes N.S., Endo I., Evangelista H.J. 2002. A Bacia de Antepaís Paleoproterozóica Sabará, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais. Revista Brasileira de Geociências, 32(1):27-42.), which requires a different system tracts classification, if compared to the rift/passive margin (classic) sequence stratigraphy, where base-level changes and sedimentation rates are the main drivers of the stratigraphic framework. In this type of basin (Foreland), the tectonic load and flexural behaviour of the lithosphere play the major roles in stratigraphic control, making the eustasy a secondary agent, or merely a consequence. For that purpose, different system tract classification is hereby proposed (Figure 11), based on its Underfilled, Filled, and Overfilled stages (Sinclair and Allen 1992Sinclair H.D., Allen P.A. 1992. Vertical versus horizontal motions in the Alpine orogenic wedge: stratigraphic response in the foreland basin. Basin Research, 4(3-4):215-232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2117.1992.tb00046.x

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/...

, Crampton and Allen 1995Crampton S.L., Allen P.A. 1995. Recognition of forebulge unconformities associated with early stage foreland basin development: Example from north Alpine foreland basin. American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, 79(10):1495-1514. https://doi.org/10.1306/7834DA1C-1721-11D7-8645000102C1865D

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1306/...

, Catuneanu 2004Catuneanu O. 2004. Retroarc foreland systems - evolution through time. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 38(3):225-242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2004.01.004

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/...

).

Foreland Basin Sequence Stratigraphy proposition and its application in Sabará and Itacolomi Groups within Minas Basin (Underfilled and Overfilled Foreland, respectively).