Abstract

In this study, we investigated the cerebroprotective effects of fenchone (FEN) against brain ischemia through in silico and in vivo approaches, focusing on the inhibition of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and the modulation of oxidative stress markers. Molecular docking revealed the potential binding affinity of FEN for the NOS active site, with a binding energy of -6.6 kcal/mol. This was validated through molecular dynamics simulations over a 100 ns time frame, demonstrating stability and favorable interaction profiles. Wistar albino rats underwent bilateral common carotid artery occlusion/reperfusion (BCCAO/R) followed by FEN administration at doses of 100 and 200 mg/kg. Our results indicated a significant reduction in cerebral infarction size and improvements in electroencephalography (EEG) signal magnitude with FEN treatment. Additionally, FEN restored the activity of antioxidant enzymes (catalase and superoxide dismutase) and decreased malondialdehyde (MDA) and nitric oxide (NO) levels and infarct size compared to those in untreated ischemic rats. Histological analysis further corroborated the neuroprotective effects of FEN, demonstrating the structural preservation of neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region. Overall, the results suggest that FEN plays a neuroprotective role in brain ischemia, potentially through the inhibition of NOS, reduction of oxidative stress, and modulation of antioxidants, highlighting the potential of FEN as a therapeutic candidate for ischemic stroke management.

Keywords:

Fenchone; Nitric oxide synthase; BCCAO/R; Cerebroprotective; In silico studies

INTRODUCTION

The human brain constitutes merely 2% of the total body mass, yet it consumes 25% of the body’s oxygen and glucose, which is imperative for sustaining electrical activity and vital functions (Nagahiro et al., 1998). Stroke poses a substantial socioeconomic challenge, exerting considerable damage on patients, their families, and society at large (Lovett et al., 2003). Stroke is the second leading cause of death globally and the third leading cause of death and disability. In India, the incidence of stroke is increasing, making it the fourth leading cause of death and the fifth leading cause of disability (Feigin et al., 2022). Worldwide, in 2019, the age-standardized incidence rate of stroke was 1240.263 per 100,000 people, with a range of 1139.711 to 1352.987 (Zhang, Lu, Yang, 2024). In India, previous studies have reported a range of 105 to 152 stroke cases per 100,000 people per year. In a population of 22,479,509 individuals, 11,654 individuals were identified as having incident stroke, resulting in an average of 1294 cases per year (Jones et al., 2022). In the USA, the age-standardized prevalence of self-reported stroke in the United States increased from 2.7% during 2011-2013 to 2.9% during 2020-2022, a 7.8% increase (Imoisili, 2024). Furthermore, strokes are responsible for approximately 11% of total mortality and are the foremost cause of disability. Stroke is a major cause of death and disability globally, and its incidence is increasing in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs). In 2024, LMICs are expected to account for more than 85% of all stroke cases, a figure that is notably higher than the rates seen in high-income countries (HICs). This disparity underscores the pressing need for effective stroke prevention and management strategies in LMICs, particularly in rural areas and among marginalized populations.(Prust, Forman, Ovbiagele, 2024) Notably, the incidence of stroke in India is exhibiting a marked increase concomitant with an increasing lifespan (Salunkhe et al., 2024). The World Stroke Organization (WSO) reports that annually, more than 12.2 million new strokes occur worldwide, nearly 16% of which occur in individuals aged 15-49 years. Additionally, there are more than 3.4 million new cases of intracerebral hemorrhage annually, accounting for more than 28% of all incident strokes (Feigin et al., 2022).

In cases of cerebral ischemia, reduced blood flow causes reduced oxygen to the brain or cerebral hypoxia, resulting in the demise of brain tissue. Ischemic strokes comprise 87% of all stroke types, with intracerebral hemorrhages accounting for 10% and subarachnoid hemorrhages accounting for 3%. The WHO has identified stroke as the second leading cause of death globally and the third leading cause of death in developed countries (Dirnagl, Iadecola, Moskowitz, 1999; Hossmann, 1994; Lo et al., 2003; Martin, Lloyd, Cowan, 1994; Moustafa, Baron, 2008).

Cerebral stroke pathophysiology involves several mechanisms, including energy depletion, free radical production, inflammation, increased intracellular Ca2+ levels, excitotoxicity, and cell death via either apoptosis or necrosis. In the necrotic pathway, rapid cytoskeletal breakdown occurs due to loss of energy. Moreover, in the apoptotic pathway, cells undergo programmed death (Ziegler, Groscurth, 2004). The deprivation of glucose leads to the inability of mitochondria to synthesize ATP (Yung, Wyttenbach, Tolkovsky, 2004). The failure to produce ATP causes membrane dysfunction, leading to neuronal depolarization and an increase in intracellular calcium levels. Subsequent depolarization prompts the release of glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter, at synaptic terminals, which in turn results in excitotoxicity. Furthermore, free radical species generated through mitochondrial dysfunction and membrane lipid degradation initiate catalytic membrane degradation and adversely affect critical cellular functions. Oxygen free radicals act as pivotal signaling molecules that induce inflammation and apoptosis (Sutherland et al., 2012). Stroke is a significant global health concern, and current treatments primarily focus on thrombolysis and endovascular interventions such as thrombectomy. However, these treatments are limited by a narrow therapeutic window and associated side effects, such as a strict treatment window and potential risks such as bleeding. As a result, there is a growing interest in exploring natural products as potential sources for stroke treatment. Natural products have been found to exert beneficial effects on stroke, particularly on neuronal protection, oxidative stress burden, and the effects of SIRT1 agonists that attenuate neuroinflammation (Fang et al., 2022; Xie et al., 2021).

Fenchone (FEN), a bicyclic monoterpene ketone prominently found in fennel oils, has piqued scientific interest due to its multifaceted pharmacological profile. Historically, FEN has been utilized for its antifungal, antidiarrheal (Pessoa et al., 2020), diuretic (Bashir et al., 2023), antitubercular (Dobrikov et al., 2014), antimicrobial (Ahmad et al., 2022), wound healing (Keskin et al., 2017), analgesic (Him et al., 2008), larvicidal (Abdel-Baki et al., 2021), and anticancer effects (Rolim et al., 2017). FEN has been investigated for its anti-inflammatory (Nawaz et al., 2023), antioxidant (Araruna et al., 2024), and other pharmacological activities (Bashir et al., 2023). This information indicates that FEN could have a beneficial effect on the brain, especially in diseases with inflammatory and oxidative components. However, its neuroprotective effects, especially cerebroprotective effects, are an upcoming field of research. It has been reported in the literature that terpenes such as FEN can cross the blood‒brain barrier and are therefore able to be used in neurologic applications (Ilić et al., 2019; Rehman et al., 2022). The structural properties of the compound allow it to interact with several enzyme systems, including nitric oxide synthase (NOS). This finding highlights the importance of NOS inhibition in the pathophysiology of cerebral ischemia, making FEN a good therapeutic molecule. This approach represents a promising candidate for the development of innovative stroke therapeutics, even in therapeutically intractable fields with few treatment options, and it is hoped that this approach may soon be recognized as a putative inhibitor of NO synthesis.

Our investigation of the cerebroprotective potential of fenchone hinged on the deployment of both in silico and in vivo experimental paradigms. In silico analyses served as a precursor, employing molecular docking and simulation techniques to predict the binding affinity of fenchone to the active site of nitric oxide synthase (NOS). This computational chemistry approach facilitated primary screening for possible inhibitory interactions, providing a landscape for subsequent in vivo validation. In vivo studies have employed a widely accepted method known as bilateral common carotid artery occlusion and reperfusion (BCCAO/R) model, which is a well-established approach. Biological markers of NOS activity and NO production, in addition to neurobehavioral outcomes, were recorded as indicators of cerebral recovery. By bridging in silico predictions with In vivo observations, our methodology aimed to evaluate the inhibitory effects of fenchone on NOS and its sequelae in ischemic brain injury.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Molecular Docking Studies

Protein Preparation

The 3D structure of the human inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) heme domain, in complex with (R)-6-(3-amino-2-(5-(2-(6-amino-methylpyridin-2-Yl) ethyl)pyridin-3-Yl)propyl)-4-methylpyridin-2-amine (CCl) (PDB ID: 4CX7), was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Guntupalli et al., 2024). The use of a cocrystallized ligand in molecular docking is important because it provides a reference for the correct binding pose of a ligand within the target protein’s active site. This detail is necessary for confirming the accuracy of docking algorithms and for understanding the molecular basis of ligand binding, which is a crucial aspect of structure-based drug design (Çinar et al., 2020). Nonprotein molecules were removed from 4CX7. We performed docking calculations with AutoDock 4.0 software (Huey, Morris, Forli, 2012). 4CX7 was generated by adding polar hydrogens and then subjected to rigid-body docking with the AutoDock tools.(Vamshi et al., 2024)

Ligand Preparation

The PubChem database was used to retrieve the two-dimensional (2D) structures of the ligands fenchone (FEN) and CCl. Furthermore, the pdb files of these ligands were converted into 3D structures in pdbqt file format using Open Babel for molecular docking studies with the MMFF94 force field. (O’boyle et al., 2011).

Molecular Docking

Redocking against cocrystallized ligands is a widely used validation method in molecular docking. This procedure involves docking a ligand back into the binding site of the protein it was originally extracted from using the original protein structure. Here, the intent is to evaluate the performance of the docking algorithm by matching a docked pose with an experimentally determined ligand conformation. The root mean square deviation of Poses (RMSD) is a method of measuring the structural similarity between the docked pose and the crystal pose of the ligand; it can be used as a quantitative metric for how well the pose of the ligand is docked; a lower RMSD implies that the ligand is docked more accurately. Molecular docking of the ligand FEN to the NOS protein was performed using AutoDock Vina (Trott, Olson, 2010). Preparation of the necessary input files for this software involved the use of AutoDock tools to add polar hydrogen atoms and assign Gasteiger charges to the molecular structures. The dimensions of the grid box were set to 10 for each of the X, Y, and Z axes, with the center of the binding site specified at the following coordinates: x = -14.213, y = -66.509, and z = 16.58. The docking application was performed by using the global search exhaustiveness of 8, which corresponds to the default option. The developers of AutoDock Vina have supplied a shell script to facilitate the use of Vina, which we employed in our docking procedures. The binding affinities of the ligands were calculated as negative values, with energies measured in kcal/mol. For every ligand processed, Vina generated nine potential binding poses, each with a distinct binding energy. We chose the pose of greatest protein‒ligand binding using an in-house developed Perl script developed to interpret the results from the docking simulations. All interactions identified between ligands and proteins were visualized and modeled using Biovia Discovery Studio 2020 Visualizer.

Molecular Dynamic Studies

The stability of the interactions within the NOS protein cavity was assessed by 100 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the structures of the complexes with selected compounds (Opo et al., 2021). The thermodynamic stability of the receptor‒ligand complexes was further evaluated by MD simulations (performed using the ‘Desmond v3.6 (Academic version) on a Linux platform (Bharadwaj et al., 2021)). A predetermined TIP3P water model was employed to solvate the system within an orthorhombic periodic boundary box, applying a 10 Å buffer in all directions to maintain the specified volume. Suitable ions, specifically Na+ and Cl-, were added at a 0.15 M concentration to the solvated system for electrical neutralization. Following this, system minimization and relaxation were conducted as per the Desmond module’s default protocols, utilizing OPLS-2005 force field parameters (Opo et al., 2021). NPT ensembles, employing Nose‒Hoover temperature coupling and isotropic scaling, were maintained at 300 K and 1.01325 bar pressure, with recording intervals of 50 PS and an energy assignment of 1.2. Molecular mechanics-generalized born surface area (MM-GBSA) was performed using the fastDRH (http://cadd.zju.edu.cn/fastdrh/overview) (Wang et al., 2022). FastDRH is an open accessed webserver that uses AutoDock Vina and AutoDock-GPU docking engines and structure-truncated MM/PB(GB)SA free energy calculation module. The combined structure-truncated MM/PB(GB)SA re-scoring processes yield a success rate of more than 80% in benchmark, which is significantly higher than AutoDock Vina (70%). In this study, we used the GAFF2 force field for ligands and ff14SB force field for the macromolecule. The truncation radius was set to 30 Å while pose rescoring (Rahman, Ahmed, 2023).

Animals

Male and female albino rats weighing between 220 and 240 grams were procured from Vyas Labs Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad, Telangana, India. These animals were housed in polypropylene cages under standard laboratory conditions, with ad libitum access to a conventional laboratory diet and water. This research received prior approval from the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (CPCSEA/IAEC/JLS/18/07/22/031).

Experimental Procedure for Cerebral Ischemia and Estimation of Biochemical Markers

Thirty Wistar albino adult rats were evenly distributed into five groups, with six rats per group: Group I included normal rats; Group II included sham-operated rats; Group III included rats with induced bilateral common carotid artery occlusion (BCCAO); Group IV included rats pretreated with 100 mg/kg body weight FEN orally for 14 days prior to BCCAO/reperfusion (BCCAO/R) surgery; and Group V included rats pretreated with 200 mg/kg body weight GBEE administered orally for the same duration, followed by BCCAO/R surgery. After three cycles, the rats were euthanized humanely, and their brains were removed for assessment of cerebral infarction size. The levels of GSH (Ellman, 1959), SOD (Marklund, Marklund, 1974), CAT, and MDA were quantified in brain homogenates (Grisham, Johnson, Lancaster, 1996).

Estimation of Nitrite Levels

Nitric oxide (NO) levels were assessed by quantifying nitrite-nitrate concentrations in rat brain homogenates immediately after decapitation. The homogenate was centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected. After that, NO production was evaluated following the Griess reaction by incubating 100 µL of supernatant with 100 µL of Griess reagent at room temperature for 10 minutes. The absorbance was measured at 550 nm by using a microplate reader, and a NaNO2 standard curve was plotted in the range of 0.75-100 µM.(Oliveira et al., 2007)

Histological studies

Different parts of the brain were fixed with a solution of freshly prepared 10% neutral buffered formalin and paraffin-embedded. These tissues were cut into 4-µm-thick sections, and the tissues were prepared for histopathological examination. Finally, the sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and then observed under a light microscope (Pasala et al., 2023).

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM; n = 3 independent experiments. Differences in group means were tested with a t test and ANOVA, and multiple comparisons were assessed with Dunnett’s test. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Molecular Docking Studies

This study aimed to elucidate the molecular features of the interaction between FEN and nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and elucidate the importance of this interaction in the pathogenesis of ischemic brain insult. Given the importance of NOS in ischemia, where nitric oxide production mediates and exacerbates neuronal damage, investigating the extent and mode of binding of FEN to NOS will be especially important. In this study, we used computational docking analyses to predict binding modes, affinities, and interaction profiles to provide insight into the neuroprotective effects of FEN.

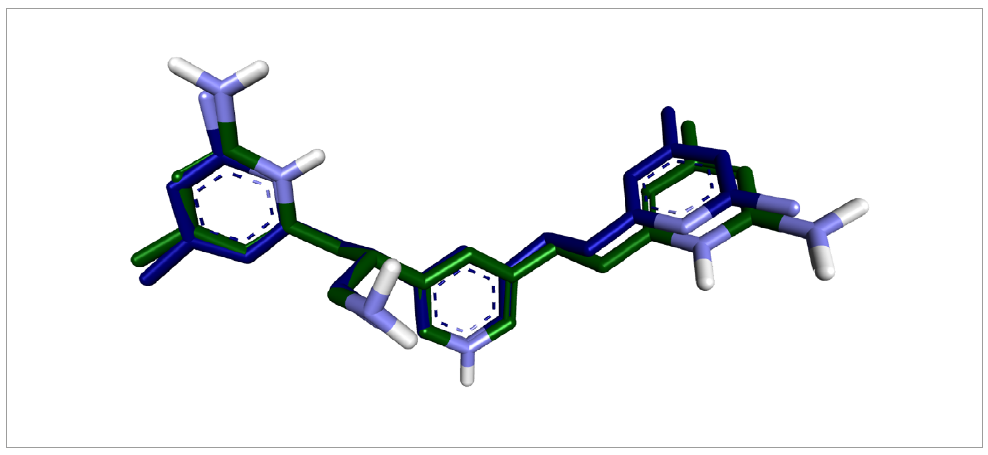

To confirm the accuracy of the docking protocol, we redocked the cocrystallized ligand into the enzyme’s active site. The resulting root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the redocked pose and the original cocrystallized structure was 0.766226 Å, which substantiates the efficacy and dependability of our docking approach (Figure 1).

Validation of the docking algorithm was accomplished by redocking the native inhibitor (CCl) with the target nitric oxide synthase (PDB ID: 4CX7). Blue represents the native crystallized pose of Cl, and green indicates the docked pose of CCl.

Table I shows the binding affinities of FEN and CCl for NOS. A free energy change (ΔG) of -6.6 kcal/mol was observed for FEN. Conversely, CCl demonstrated a slightly greater affinity toward NOS, with a ΔG of -7.4 kcal/mol. The variance in binding energies between FEN and CCl highlights the different molecular interactions that are imperative for the stability of each respective ligand-enzyme complex. The moderate binding affinity of FEN relative to that of CCl is due to the absence of hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions, which are critical for strong ligand‒protein binding. The presence of these interactions in CCl rats results in a more negative binding affinity, indicating stronger binding to NOS. These findings contribute foundational insights into the molecular underpinnings of how these agents might influence NOS activity, which plays an essential role in the pathophysiology of ischemic brain damage.

Binding energies and interaction mechanisms between FEN and CCl with nitric oxide synthase (NOS)

FEN predominantly forms hydrophobic contacts with the arginine residue ARG A:381. However, CCl establishes both hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions with additional residues such as TYR A:347, GLU A:377, and ASP A:382. It is evident from the binding affinity data that CCl forms stronger interactions with NOS than with FEN, as reflected by its lower ΔG value. While FEN engages mainly through hydrophobic interactions with a pivotal arginine residue, CCl utilizes a more complex interaction network, including hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions with several amino acids (Figures 2 and 3).

Molecular docking studies of FEN and NOS. (A) 2D view of the interactions of FEN with NOS. (B) 3D view of the interactions of FEN with NOS.

Molecular docking studies of CCl and NOS. (A) 2D view of the interactions of CCl with NOS. (B) 3D view of the interactions of FEN with NOS.

Molecular Simulation Studies

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are effective for assessing the stability of protein-ligand complexes under specific and controlled conditions. Accordingly, the study implemented a 100 ns MD simulation to evaluate the stability and conformational integrity of these complexes. The simulations included both docked complexes and a known reference antagonist (CCL) that interacts with NOS, providing a comparative stability perspective for protein-ligand interactions. The MD simulation results were analyzed using key parameters, including RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and principal component analysis (PCA).

The RMSD results revealed that the NOS-CCL and NOS-FEN complexes exhibited stability over the 100 ns simulation timeframe, indicating that the docked complexes sustain their structural integrity with minimal fluctuations. The average RMSD for NOS-CCL was 2.93 ± 0.2 Å, while that for NOS-FEN was 3.14 ± 0.1 Å, which further substantiates their stability during the simulation, as shown in Figure 4A. To assess the compactness and dynamic stability of the NOS-CCL and NOS-FEN complexes, the radius of gyration (Rg) was analyzed and is shown in Figure 5. The Rg values obtained were 23.02 ± 0.08 Å for the NOS-CCL complex and 22.84 ± 0.13 Å for the NOS-FEN complex. The simulation results support the hypothesis that the complex formed by the alignment of CCL with FEN on NOS maintains its stability throughout the simulation duration, as indicated in Figure 4B. The stability of protein‒ligand interactions is critically influenced by the formation of hydrogen bonds. In our study, we examined the temporal behavior of hydrogen bonds between NOS and its ligands, CCL and FEN. The time-dependent analysis is visualized in Figure 5, which shows that up to four hydrogen bonds can form between NOS and each ligand, CCL and FEN, despite noticeable fluctuations. Our findings demonstrate that the docked complexes remained stable throughout the simulations, underpinned by a consistent presence of 3 to 12 hydrogen bonds with CCL and 1 to 3 with FEN.

Conformational dynamics of the NOS2-CCL and NOS2-FEN complexes. (A) RMSD (B) Radius of gyration (Rg).

Intermolecular hydrogen bonds between (A) NOS2 and (B) FEN and between NOS2 and CCl during the simulation time.

Furthermore, to understand the collective motions within the NOS-CCL and NOS-FEN complexes, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed. The leading eigenvectors (EVs) have a significant impact on the overall movement of a protein. PCA was therefore utilized to investigate the conformational dynamics of these complexes during the simulations, as depicted in Figure 6. The PCA time evolution profile shows a reduction in the flexibility of the NOS-CCL and NOS-FEN complexes across these EVs, suggesting increased stability. The corresponding plot demonstrates that the two complexes explored nearly all available conformational space, with their movements substantially overlapping.

Free energy landscape (FEL) analysis serves as a prominent method for exploring protein folding mechanisms and overall stability. FEL plots illustrate the most energetically favorable conformational ensembles for a given protein structure. In this study, we produced FEL plots for PC1 and PC2 (Figure 6A), with regions of deeper blue denoting more stable protein conformations at lower energy levels. These plots display energy values that span from 0 to 16 kJ/mol over the course of the NOS-CCL and NOS-FEN simulations. The FEL plots demonstrate a single global minimum for both the NOS-CCL and NOS-FEN complexes, which are localized within a broad local basin. These results indicate that neither CCL nor FEN induces significant conformational alterations in the NOS structure, suggesting their role in its stabilization (Figure 6B).

The binding free energies for the compounds FEN and CCl were evaluated using the MMGBSA method, and the results are presented in the Table II. Non-covalent interactions are evident from the VDW contribution of FEN (-33.7 kcal/mol) and CCl (-46.62 kcal/mol). In case of both compounds the electrostatic (ELE) contributions are zero and this is indicative of no net charge interaction within the system. Polar solvation energy were estimated with the Generalized Born (GB) solvation model which provide 7.75 kcal/mol and 15.45 kcal/mol for FEN and CCl, respectively, indicating the impact of solvation effect in a polar environment. The solvent-accessible surface area (SA) contributions, that is, the nonpolar solvation energy, are -2.22 kcal/mol for FEN and -3.57 kcal/mol for CCl. The complete values of the binding free energies are -28.31 kcal/mol with respect to the FEN ligand and -34.9 kcal/mol in relation with the CCl. The binding affinities were fairly strong for both compounds though CCl had slightly more favorable binding energy than FEN-binding was due primarily to larger Van der Waals and polar solvation contributions for CCl, while total entropy was similarly on the favorable side for both compounds. This highlights the significance of combining solvation and non-covalent contributions in the binding affinity computations of molecular systems.

Effect of FEN on the Percentage of Infarct Size in BCCAO/R Rats

The comparative analysis of cerebral infarction across different treatment groups revealed statistically significant differences in the degree of ischemic damage. In the normal and sham control groups, cerebral infarction was minimal, with infarct sizes of 0.1% and 0.21%, respectively, reflecting negligible ischemic injury. Conversely, 89.4% of BCCAO/R rats exhibited markedly elevated cerebral infarction, underscoring severe ischemic insult following bilateral common carotid artery occlusion and subsequent reperfusion. Treatment with fenchone at either dose, 100 mg/kg or 200 mg/kg, resulted in a substantial reduction in cerebral infarction percentages, which were 55.2% and 39.1%, respectively (Figure 7).

The impact of FEN on the extent of cerebral infarction across various experimental rat groups: (a) control rats, (b) sham-operated rats, (c) rats subjected to BCCAO/R, (d) BCCAO/R rats treated with 100 mg/kg body weight FEN, and (d) BCCAO/R rats treated with 200 mg/kg body weight FEN.

Effect of FEN on brain tissue parameters in BCCAO/R rats

Biochemical assessments revealed significant changes in oxidative stress markers and the antioxidant defense system across different experimental cohorts. Compared with both the normal and sham control groups, the bilateral common carotid artery occlusion/reperfusion (BCCAO/R) group exhibited pronounced decreases in the activities of CAT, GSH, and SOD, accompanied by increases in malondialdehyde (MDA) levels. These findings are indicative of increased oxidative stress and defective antioxidant defense under these disease conditions. (Pasala et al., 2022). Dose-dependent improvements in the measured parameters were observed after the administration of FEN at doses of 100 mg/kg and 200 mg/ kg to Groups IV and V, respectively. Treatment with FEN caused an increase in catalase and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity and a decrease in malondialdehyde (MDA) and glutathione (GSH) concentrations. These results suggest that FEN reduces oxidative injury and lipid peroxidation. Moreover, NO levels, which may reflect anti-inflammatory effects, were significantly decreased in FEN-treated animals. These findings confirm that fenchone is a promising candidate for attenuating oxidative stress and inflammation in a pathophysiological manner similar to that underlying bilateral common carotid artery occlusion/reperfusion (BCCAO/R)-associated brain injury and support its neuroprotective effect. Further comprehensive mechanistic studies should be pursued to decipher the exact molecular mechanisms underlying the advantageous impact of Fenchone on cerebral biochemistry (Figure 8 and Table III).

The impact of fenchone on brain biochemical parameters in BCCAO/R rats; levels of (A) superoxide dismutase (SOD), (B) catalase, (C) malondialdehyde (MDA), (D) glutathione (GSH), and (E) nitric oxide (NO). The data are expressed as the mean values ± standard deviations (n=8). Analysis of the data was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with differences among the means followed by Dunnett’s test for pairwise comparisons. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Among terpenes, pinene and linalool have emerged as promising candidates for improving brain health because of their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective properties (Weston-Green, Clunas, Jimenez Naranjo, 2021). These terpenes have shown the ability to mitigate oxidative stress and inflammation, which are key factors contributing to neuronal damage during cerebral ischemia. Additionally, terpinen-4-ol, another terpene found in the Pistacia genus, has been identified as a neuroprotective substance, further highlighting the potential of terpenes in safeguarding brain health (Moeini et al., 2019). The neuroprotective mechanisms of terpenes involve the modulation of pathways such as the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway, which plays a crucial role in antioxidant defense and cellular protection (Xu et al., 2022). Based on these results, FEN appears to have a neuroprotective effect, likely due to its ability to reduce oxidative stress and increase antioxidant levels. FEN also acts as a regulator of nitric oxide synthase (NOS), preventing the production of nitric oxide (NO) and thereby influencing various physiological and pathological processes in the brain.

EEG Recording and Analysis

In contrast to those in the control and sham groups, rats subjected to bilateral common carotid artery occlusion/ reperfusion (BCCAO/R) demonstrated unsynchronized polyspikes and slow-wave patterns with diminished amplitude. EEG recordings from control and sham-treated rats revealed a signal magnitude range of -0.25 to 0.25 without the presence of abnormal spikes. In contrast, BCCAO/R rats presented a decreased signal magnitude range of <-0.5 to 0.5, accompanied by anomalous spikes. Treatment of BCCAO/R rats with fenchone (100 mg/ kg body weight (B.w.t.) or per os (p.o.)) resulted in an increase in EEG signal magnitude with a reduction in spike frequency. However, pretreatment with a higher dose of fenchone (200 mg/kg, B.w.t., p.o.) effectively normalized the magnitude of the EEG signal and further minimized spike occurrence (Figure 9).

The EEGs of rats treated with the drug are shown with a filter of 0.1 Hz for the low end and 99 Hz for the high end, with a sensitivity of 30 µV and a sweep speed of 30 mm/sec. The results are presented for normal rats (A), sham rats (B), diseased rats (C), rats treated with 100 mg/kg fenchone (D), and rats treated with 200 mg/kg fenchone (E).

Effect of FEN on Hippocampal CA1 Neuronal Histology

Histological examination using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed that the CA1 neurons in the hippocampus of both normal and sham-operated rats displayed a structured and organized arrangement, with the neuronal cytoplasm being lightly stained. In contrast, the bilateral common carotid artery occlusion/reperfusion (BCCAO/R) group exhibited disorganized cell layers, with some neurons exhibiting darkly stained cytoplasm and a reduced cell size. However, treatment with fenchone at a dose of 200 mg/kg, administered per os (p.o.), resulted in an improvement in the neuronal arrangement within the hippocampal CA1 region, as well as a decrease in the intensity of cytoplasmic staining, in comparison to the group treated with a lower fenchone dose of 100 mg/kg p.o. (refer to Figure 10).

Histopathological analysis of the hippocampus in the brain revealed four distinct groups: normal rats (A), sham rats (B), diseased rats (C), and two groups of rats treated with 100 mg/kg (D) and 200 mg/kg (E) fenchone. The red arrow indicates normal pyramidal cells with prominent nuclei and a dense arrangement, while the yellow arrow highlights pyramidal cells exhibiting chromatid condensation and apoptotic cells.

CONCLUSIONS

Molecular docking and dynamics simulations, together with compelling In vivo evidence of reduced neural infarction, improved EEG signatures, and the preservation of crucial oxidative markers, have led to the identification of fenchone as a formidable candidate for ischemic stroke therapeutics. These findings underscore the neuroprotective properties of FEN, which are mediated through the regulation of the ROS/RNS pathway. This study lays the foundation for further research, particularly clinical trials, to validate the translational efficacy of Fenchone and to establish its role within the canon of stroke management.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the management of the Sri Indu Institute of Pharmacy, Ibrahimpatnam, Rangareddy, and Telangana for providing the facilities to perform the study.

REFERENCES

- Abdel-Baki AaS, Aboelhadid SM, Sokmen A, Al-Quraishy S, Hassan AO, Kamel AA. Larvicidal and pupicidal activities of foeniculum vulgare essential oil, trans-anethole and fenchone against house fly musca domestica and their inhibitory effect on acetylcholinestrase. Entomol Res. 2021;51(11):568-577.

-

Ahmad W, Ansari MA, Yusuf M, Amir M, Wahab S, Alam P, et al. Antibacterial, anticandidal, and antibiofilm potential of fenchone: In vitro, molecular docking and in silico/admet study. Plants (Basel). 2022;11(18). doi:10.3390/plants11182395.

» https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11182395 -

Araruna MEC, Junior EBA, Serafim CaL, Pessoa MMB, Pessoa MLS, Alves VP, et al. (-)-fenchone prevents cysteamine-induced duodenal ulcers and accelerates healing promoting re-epithelialization of gastric ulcers in rats via antioxidant and immunomodulatory mechanisms. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;17(5). doi:10.3390/ ph17050641.

» https://doi.org/10.3390/ ph17050641 -

Bashir A, Mushtaq MN, Younis W, Anjum I. Fenchone, a monoterpene: Toxicity and diuretic profiling in rats. Front Pharmacol. 2023;141119360. doi:10.3389/ fphar.2023.1119360.

» https://doi.org/10.3389/ fphar.2023.1119360 -

Bharadwaj S, Dubey A, Yadava U, Mishra SK, Kang SG, Dwivedi VD. Exploration of natural compounds with anti-sars-cov-2 activity via inhibition of sars-cov-2 mpro. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22(2):1361-1377. doi:10.1093/ bib/bbaa382.

» https://doi.org/10.1093/ bib/bbaa382 - Çinar I, Aksoy İ, Güler G, editors. Spectroscopic and computational molecular docking studies on the protein-drug interactions. 2020 Medical Technologies Congress (TIPTEKNO); 2020 19-20 Nov. 2020.

-

Dirnagl U, Iadecola C, Moskowitz MA. Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: An integrated view. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22(9):391-397. doi:10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01401-0.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01401-0 -

Dobrikov GM, Valcheva V, Nikolova Y, Ugrinova I, Pasheva E, Dimitrov V. Enantiopure antituberculosis candidates synthesized from (-)-fenchone. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;77243-247. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.03.025.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.03.025 -

Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82(1):70-77. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6 -

Fang C, Xu H, Yuan L, Zhu Z, Wang X, Liu Y, et al. Natural compounds for sirt1-mediated oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in stroke: A potential therapeutic target in the future. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;20221949718. doi:10.1155/2022/1949718.

» https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1949718 -

Feigin VL, Brainin M, Norrving B, Martins S, Sacco RL, Hacke W, et al. World stroke organization (wso): Global stroke fact sheet 2022. Int J Stroke. 2022;17(1):18-29. doi:10.1177/17474930211065917.

» https://doi.org/10.1177/17474930211065917 -

Grisham MB, Johnson GG, Lancaster JR, Jr. Quantitation of nitrate and nitrite in extracellular fluids. Methods Enzymol. 1996;268237-246. doi:10.1016/s0076-6879(96)68026-4.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/s0076-6879(96)68026-4 - Guntupalli C, Ponugoti M, Prasanth D, Malothu N. Cerebroprotective effects of khellin: Validation through computational studies in a bilateral common carotid artery occlusion/reperfusion (bccao/r) model. Mol Simul. 2024;1-10.

- Him A, Ozbek H, Turel I, Oner AC. Antinociceptive activity of alpha-pinene and fenchone. Pharmacologyonline. 2008;3363-369.

-

Hossmann KA. Viability thresholds and the penumbra of focal ischemia. Ann Neurol. 1994;36(4):557-565. doi:10.1002/ana.410360404.

» https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410360404 - Huey R, Morris GM, Forli S. Using autodock 4 and autodock vina with autodocktools: A tutorial. The Scripps Research Institute Molecular Graphics Laboratory. 2012;10550(92037): 1000.

- Ilić DP, Stanojević LP, Troter DZ, Stanojević JS, Danilović BR, Nikolić VD, et al. Improvement of the yield and antimicrobial activity of fennel (foeniculum vulgare mill.) essential oil by fruit milling. Ind Crops Prod. 2019;142111854.

- Imoisili OE. Prevalence of stroke-behavioral risk factor surveillance system, united states, 2011-2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73.

-

Jones SP, Baqai K, Clegg A, Georgiou R, Harris C, Holland EJ, et al. Stroke in india: A systematic review of the incidence, prevalence, and case fatality. Int J Stroke . 2022;17(2):132-140. doi:10.1177/17474930211027834.

» https://doi.org/10.1177/17474930211027834 -

Keskin I, Gunal Y, Ayla S, Kolbasi B, Sakul A, Kilic U, et al. Effects of foeniculum vulgare essential oil compounds, fenchone and limonene, on experimental wound healing. Biotech Histochem. 2017;92(4):274-282. doi:10.1080/1 0520295.2017.1306882.

» https://doi.org/10.1080/1 0520295.2017.1306882 -

Lo EH, Dalkara T, Moskowitz MA. Mechanisms, challenges and opportunities in stroke. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4(5):399-415. doi:10.1038/nrn1106.

» https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1106 -

Lovett JK, Dennis MS, Sandercock PA, Bamford J, Warlow CP, Rothwell PM. Very early risk of stroke after a first transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2003;34(8):e138-140. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000080935.01264.91.

» https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000080935.01264.91 -

Marklund S, Marklund G. Involvement of the superoxide anion radical in the autoxidation of pyrogallol and a convenient assay for superoxide dismutase. Eur J Biochem. 1974;47(3):469-474. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974. tb03714.x.

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974. tb03714.x -

Martin RL, Lloyd HG, Cowan AI. The early events of oxygen and glucose deprivation: Setting the scene for neuronal death? Trends Neurosci . 1994;17(6):251-257. doi:10.1016/0166-2236(94)90008-6.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-2236(94)90008-6 -

Moeini R, Memariani Z, Asadi F, Bozorgi M, Gorji N. Pistacia genus as a potential source of neuroprotective natural products. Planta Med. 2019;85(17):1326-1350. doi:10.1055/a-1014-1075.

» https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1014-1075 -

Moustafa RR, Baron JC. Pathophysiology of ischaemic stroke: Insights from imaging, and implications for therapy and drug discovery. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S44-54. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707530.

» https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0707530 - Nagahiro S, Uno M, Sato K, Goto S, Morioka M, Ushio Y. Pathophysiology and treatment of cerebral ischemia. J Med Invest. 1998;45(1):57-70. doi:NA.

-

Nawaz S, Irfan HM, Alamgeer, Arshad L, Jahan S. Attenuation of cfa-induced chronic inflammation by a bicyclic monoterpene fenchone targeting inducible nitric oxide, prostaglandins, c-reactive protein and urea. Inflammopharmacology. 2023;31(5):2479-2491. doi:10.1007/s10787-023-01333-7.

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-023-01333-7 -

O’boyle NM, Banck M, James CA, Morley C, Vandermeersch T, Hutchison GR. Open babel: An open chemical toolbox. J Cheminform. 2011;333. doi:10.1186/1758-2946-3-33.

» https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2946-3-33 - Oliveira A, Almeida J, Freitas R, Nascimento V, Aguiar L, Júnior H, et al. Effects of levetiracetam in lipid peroxidation level, nitrite-nitrate formation and antioxidant enzymatic activity in mice brain after pilocarpine-induced seizures. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2007;27395-406.

-

Opo F, Rahman MM, Ahammad F, Ahmed I, Bhuiyan MA, Asiri AM. Structure based pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening, molecular docking and admet approaches for identification of natural anti-cancer agents targeting xiap protein. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4049. doi:10.1038/ s41598-021-83626-x.

» https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598-021-83626-x -

Pasala PK, Abbas Shaik R, Rudrapal M, Khan J, Alaidarous MA, Jagdish Khairnar S, et al. Cerebroprotective effect of aloe emodin: In silico and in vivo studies.Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022;29(2):998-1005. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.09.077.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.09.077 -

Pasala PK, Donakonda M, Dintakurthi PSNBK, Rudrapal M, Gouru SA, Ruksana K. Investigation of cardioprotective activity of silybin: Network pharmacology, molecular docking, and in vivo studies. ChemistrySelect. 2023;8(20):e202300148. doi:10.1002/slct.202300148.

» https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202300148 -

Pessoa MLS, Silva LMO, Araruna MEC, Serafim CaL, Junior EBA, Silva AO, et al. Antifungal activity and antidiarrheal activity via antimotility mechanisms of (-)-fenchone in experimental models. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26(43):6795-6809. doi:10.3748/ wjg.v26.i43.6795.

» https://doi.org/10.3748/ wjg.v26.i43.6795 -

Prust ML, Forman R, Ovbiagele B. Addressing disparities in the global epidemiology of stroke. Nat Rev Neurol. 2024;20(4):207-221. doi:10.1038/s41582-023-00921-z.

» https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-023-00921-z - Rahman MO, Ahmed SS. Anti-angiogenic potential of bioactive phytochemicals from helicteres isora targeting vegfr-2 to fight cancer through molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2023;41(15):7447-7462.

-

Rehman NU, Ansari MN, Samad A, Ahmad W. In silico and ex vivo studies on the spasmolytic activities of fenchone using isolated guinea pig trachea. Molecules. 2022;27(4):1360. doi:10.3390/molecules27041360.

» https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27041360 - Rolim TL, Meireles DRP, Batista TM, De Sousa TKG, Mangueira VM, De Abrantes RA, et al. Toxicity and antitumor potential of mesosphaerum sidifolium (lamiaceae) oil and fenchone, its major component. BMC Complementary Altern Med. 2017;17(1):1-12.

-

Salunkhe M, Haldar P, Bhatia R, Prasad D, Gupta S, Srivastava MVP, et al. Impetus stroke: Assessment of hospital infrastructure and workflow for implementation of uniform stroke care pathway in india. Int J Stroke . 2024;19(1):76-83. doi:10.1177/17474930231189395.

» https://doi.org/10.1177/17474930231189395 -

Sutherland BA, Minnerup J, Balami JS, Arba F, Buchan AM, Kleinschnitz C. Neuroprotection for ischaemic stroke: Translation from the bench to the bedside. Int J Stroke . 2012;7(5):407-418. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00770.x.

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00770.x -

Trott O, Olson AJ. Autodock vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(2):455-461. doi:10.1002/jcc.21334.

» https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21334 -

Vamshi G, D SNBKP, Sampath A, Dammalli M, Kumar P, B SG, et al. Possible cerebroprotective effect of citronellal: Molecular docking, md simulation and in vivo investigations. J Biomol Struct Dyn . 2024;42(3):1208-1219. doi:10.1080/07391102.2023.2220025.

» https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2023.2220025 - Wang Z, Pan H, Sun H, Kang Y, Liu H, Cao D, et al. Fastdrh: A webserver to predict and analyze protein-ligand complexes based on molecular docking and mm/pb (gb) sa computation. Briefings Bioinf. 2022;23(5):bbac201.

-

Weston-Green K, Clunas H, Jimenez Naranjo C. A review of the potential use of pinene and linalool as terpene-based medicines for brain health: Discovering novel therapeutics in the flavours and fragrances of cannabis. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12583211. doi:10.3389/ fpsyt.2021.583211.

» https://doi.org/10.3389/ fpsyt.2021.583211 -

Xie Q, Li H, Lu D, Yuan J, Ma R, Li J, et al. Neuroprotective effect for cerebral ischemia by natural products: A review. Front Pharmacol . 2021;12607412. doi:10.3389/ fphar.2021.607412.

» https://doi.org/10.3389/ fphar.2021.607412 -

Xu L, Gao Y, Hu M, Dong Y, Xu J, Zhang J, et al. Edaravone dexborneol protects cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury through activating nrf2/ho-1 signaling pathway in mice. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2022;36(5):790-800. doi:10.1111/fcp.12782.

» https://doi.org/10.1111/fcp.12782 -

Yung HW, Wyttenbach A, Tolkovsky AM. Aggravation of necrotic death of glucose-deprived cells by the mek1 inhibitors u0126 and pd184161 through depletion of atp. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68(2):351-360. doi:10.1016/j. bcp.2004.03.030.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j. bcp.2004.03.030 -

Zhang L, Lu H, Yang C. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke from 1990 to 2019: A temporal trend analysis based on the global burden of disease study 2019. Int J Stroke . 2024;0(0):17474930241246955. doi:10.1177/17474930241246955.

» https://doi.org/10.1177/17474930241246955 -

Ziegler U, Groscurth P. Morphological features of cell death. News Physiol Sci. 2004;19(3):124-128. doi:10.1152/nips.01519.2004.

» https://doi.org/10.1152/nips.01519.2004

Data availability

None

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

20 Jan 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

12 Apr 2024 -

Accepted

04 July 2024

Unraveling cerebroprotective potential of fenchone: A combined in vivo and in silico exploration of nitric oxide synthase modulation

Unraveling cerebroprotective potential of fenchone: A combined in vivo and in silico exploration of nitric oxide synthase modulation