Abstract

This paper analyzes the risk negotiation strategies developed by Latin American women backpackers to overcome both territorial and subjective boundaries. Anchored in a “traveling ethnography”, we explore the gendered dimensions of Latin American borders from a feminist perspective. Backpacking is a negotiated and planned activity, executed through forms of agency that work to deconstruct the road as a “dangerous place” for women, destabilizing fear of/on the border.

Keywords

Borders; Gender; Risk; Women; Latin America

Resumo

O objetivo deste artigo, ancorado numa “etnografia viajante”, é analisar estratégias de negociações de risco que mulheres latino-americanas viajantes de mochila desenvolvem para romper com fronteiras territoriais e subjetivas. Nele, exploramos as dimensões de gênero das fronteiras latino-americanas numa perspectiva feminista. A viagem de mochila é uma atitude negociada, planejada e executada por meio de agenciamentos que atuam na desconstrução da estrada como um “lugar perigoso” para as mulheres, desestabilizando o medo da/na fronteira.

Palavras-chave

Fronteiras; Gênero; Risco; Mulheres; América Latina

Crossing the Departure Platform

Tietê Bus Terminal, São Paulo, the largest in Latin America and the second largest in the world. It was November 2017. Lanna arrived at the terminal with a large blue backpack1 strapped to her shoulders and an attack backpack2 in front of her. In addition to the weight of her bags, she described feeling a tangle of sensations in her body, which at the time she was unable to identify. She recalls that the excitement of the departure, alone, provoked anxiety and a fear that left her momentarily paralyzed, making her “like a zombie”. Her parents had driven Lanna to the terminal and accompanied her as far as one of its eighty-nine departure platforms. Before crossing her first border by passing the barrier onto the platform, her mother hugged her tightly, cried, and said:

— You don’t need to run away, you don’t have to prove anything to anyone. If you want to back out, there’s still time.

Lanna said that, still paralyzed, she was unable to cry, but she was determined to get on that bus headed to Chuí, on the Brazilian border with Uruguay.

— No, mom. I want to go. I want to go.

Her mother hugged her again and said:

— Alright, then come back once you’ve reached Mexico!

And with that, she boarded for her seven-month solo journey backpacking through Latin America.

The presence of women in the world of travel, which we call here the road, has disrupted the notions of fear and danger traditionally associated with women’s journeys, especially those involving the crossing of transnational borders. From a gendered historical perspective, men’s journeys have tended to be framed as heroic experiences, while women’s travels are often viewed as either dangerous or inconsequential. The travel phenomenon has long been centered on male viewpoints,3 obscuring women’s movements and presences in these spaces as unique and socially meaningful experiences. This points to the need to reflect on borders through the lenses of gender and power as constitutive dynamics of movement.

The limits and possibilities of women’s mobility across Latin America have been tested and shaped by the itineraries of women who cross transnational borders, mobilizing multiple layers of gender construction. Lanna (a 27-year-old white journalist), born in the state of São Paulo, traced a route that crossed multiple spatial borders (land, air and sea) throughout Latin America over her seven month journey from Brazil to Mexico, an experience she described as a mochilão (backpacking trip). Before setting off, she planned her expenses, organized her itinerary, bought necessary equipment, calculated the risks and challenged social conventions. Even so, she began her journey with fear as a travel companion. On the road, she discovered both her own limits and the exaggerations involved in many of the precautionary warnings. She acknowledged the need for care, but considered herself strategically-minded and intelligent. To keep herself safe, she drew on the everyday survival skills acquired from living in a major metropolis like São Paulo. “We women who live in big cities were born with a chip”, Lanna said. Like the other women featuring in this research, Lanna’s experience on the road reveals the multiple sociocultural dimensions of a physical and subjective space in continuous formation. Backpacking has become a highly visible social phenomenon of the twenty-first century, reflecting new ways of moving about in this era of “hyper-mobilities”. Today’s global flow of people makes it seem like we inhabit a connected world. But are borders really that fluid? What do the border experiences of women travelers reveal? Is there truly a gender to borders?

This article focuses on the strategies and negotiations developed by Latin American women backpackers to transcend spatial and subjective borders as they construct their diverse itineraries. Among the key categories involved in these experiences of the road is the notion of risk. Aiming to understand the negotiations embedded in travel projects, we seek to contextualize border-crossing experiences, question motivations, and interpret the agencies produced through these strategies and modalities of organization.

Ethnographically, we explore the question of what kind of borders arise in the journeys taken by women travelers. In the research, which resulted in a doctoral thesis, we engaged4 with ten women and their journeys. Through this “traveling ethnography” and a feminist theoretical-methodological approach, combined with multi-sited research, we embraced backpacking — understood here as the act of throwing one’s body into the world, which one of the authors herself undertook5 — as a methodological strategy to locate and accompany the travelers on the road. We also activated other research spaces, including Instagram. In addition, we used interviews to engage with the narratives of our interlocutors, which helped us organize and systematize the fragments.

This ethnographic experience allows us to uncover certain dimensions of borders within the practical experiences of travel. Abu-Lughod (2000) argues that ethnography is capable of delineating systems of power and structures of inequality, allowing research to transform into an instrument for intervention. We describe the paths taken by concrete subjects who experience travel by deploying strategies shaped by their perceptions of “being a female body” on the road without male company. We argue that the risk attributed to women’s behavior when crossing borders is a social construct (Yang, 2017) and that women’s travel is neither an act of sudden madness nor a rash impulse. Women are not inherently more likely to fall victim to violence due to some inherent vulnerability, as so often suggested. On the contrary, their journeys involve negotiation and planning, which are central to the forms of agency and safety strategies they adopt. The agencies (Ortner, 2007) activated throughout the journey enable a deconstruction of the “dangerous place” so often associated with border crossings. Travel reveals a constant oscillation between the pleasure of achievement and the challenge of adversity, between experiencing fulfillment and managing the risks associated with journeys. This oscillation, in turn, applies not only to physical borders but also to a complex web of crossings (spatial, subjective and bodily) embedded in the activity of backpacking. Among these relations are the power structures shaped by gender, race and class inequalities, especially in terms of the subjective impacts involved in being on the road.

Along these lines, we highlight a notion of border amply discussed in anthropology, conceived as a passage from one state to another and situated within dynamic processes of cultural crossing (Falhauber, 2001). These encounters and crossings are themselves processes in which boundaries are always fluid and subject to continual redefinition according to context, destabilizing fixed references and drawing us into discussions in the symbolic field. The border, then, is not a static line but a space of ongoing production, a fluid territory in constant transformation. Hence, the act of crossing established limits, limits that crystallize borders as dangerous spaces, is being accepted as a challenge by women through their journeys, their movements, their actions and their lived experiences on the road.

Women, Mobility and Danger on Latin American Borders

Backpacking began to take root in the imagination of young Westerners primarily from the 1960s onwards — a period marked by wars, dictatorships and other global events that forced migrations and displacements on multiple scales. This era also saw the emergence of countercultural travel practices involving groups of people with “a sense of belonging to an international youth community” (Kaminski; Vieira, 2020:9) at a time when young people from different parts of the world longed for life on the road. It was in this period that backpacking developed as a distinct way of traveling.

Women, too, were mapping out and occupying their own itineraries. Their presence can be associated with an ideological and historical moment marked by the growing visibility of women, the political affirmation of the body, libertarianism and anti-colonial political struggles. Ângela Xavier (2011) and Beatriz Sarlo (2015) documented their travel experiences during the 1960s and 1970s. They were engaged in university life and politics during a time of significant social transformation, when marriage was no longer perceived as the only life option available to women. Around the same time, Che Guevara was popularizing ideas of freedom, becoming especially known for blending travel and politics.

With the popularization of the backpacking phenomenon in Latin America at the beginning of the twenty-first century, women’s movements and displacements became increasingly visible. This was a time of cultural, economic and social transformation in the early years of the new century. The spread of internet access and the acceleration of transportation flows profoundly changed how people and ideas moved throughout the region. Expanded access to spaces such as universities and the labor market were among the factors contributing to the inclusion of women in these mobilities, producing unique, individual and collective travel experiences.

The expansion of digital networks and virtual platforms allowed information to be shared much more widely, making it easier to read and hear the narratives of travelers from diverse locations, although these testimonies predominantly reflected the kinds of mobility experienced by women from socially privileged racial and class backgrounds. Within this flow of information, content such as “lists of safest countries for women traveling alone,” “safe destinations for women,” and “women’s safety tips for solo travel” began to circulate via blogs, websites and social media accounts. This was accompanied by a proliferation of books written by women on the topic, especially with the rise of digital publishing. It became increasingly common to encounter travel narratives in blogs, books, podcasts and news features, especially within the fields of tourism and journalism. The idea of individual journeys began to shape the imaginations of the younger generations globally, including Latin Americans.

The idea of travel and free movement as a human right thus gained traction a little over two decades ago. This expansion has accompanied the increasing social mobility of women seeking gender equality and broader access to spaces where they can exercise their freedom to live and relocate how they want. Both within and beyond political participation, women have been occupying public and virtual spaces to discuss diverse aspects of their lives, including mobility and ways of navigating the world.

This topic began to resonate more strongly within networks of women travelers, taking on a political meaning after the femicide of two backpackers, María José Coni and Marina Menegazzo, in Ecuador in 2016. This networked movement quickly acquired a global dimension, fomenting discussions on gender-based violence on the road. Piscitelli (2017) and Yang (2017) observe that this violent episode prompted a debate that circulated widely, particularly on social media platforms, on the right of women travelers to make their journeys in safety.

Piscitelli (2017) argues that discussions about violence against tourists only became a prominent feminist issue when they entered the online sphere, where a new generation of women began to demand the guarantee of their rights. The internet became a key space for mobilization. This was exemplified by the #ViajoSola (#ITravelAlone) movement, a response to the murder of the two Argentine backpackers that mobilized women from around the world, who expressed themselves through social media using hashtags to defend the right to travel alone and safely.

Numerous women travelers shared personal accounts, telling their own stories of solo travel. Letters, manifestos and articles were published. One particular letter went viral during this period: “They Killed Me Yesterday” by Paraguayan writer Guadalupe Acosta. The text was a direct response to the notion that travel is inherently dangerous for women, aimed at countering the victim-blaming discourse perpetuated in the global media, which accused the backpackers of reckless or risky behavior simply for traveling “alone”, even though the two Argentine women had been together. The imposition of fear emerges here as one element to be confronted within the broader context of gender inequalities and norms that govern spaces, bodies and desires, and which are made evident in women’s subjective experiences.

At the end of 2023, another case of violence on the road reignited the debate on the dangers of travel. The cycle traveler Julieta Hernández was murdered in northern Brazil while trying to cross the border from her home country, Venezuela. The outcry surrounding her femicide again mobilized global discussions around violence and the dangers posed to women travelers. Nearly a decade after the murder of the Argentine backpackers, Julieta too was blamed for her brutal death. “What was she doing alone in that place?” was a recurring question in the media. From a female and feminist perspective, the discussion once again expanded to include the right to travel without fear and to demand an end to violence.

Violence against women, therefore, is a theme that permeates the experiences of women travelers. In this sense, framing risk as an analytical category helps us think about how women manage representations of danger and fear, as well as the difficulties and obstacles they encounter on the road. Risk takes on specific connotations in a region deeply marked by gender-based violence and racism, themselves outcomes of the inequalities forged through colonialism and coloniality. As Lugones (2018) and Gonzalez (2020) cogently argue, these dynamics are defined by the interplay of class, race and gender. At the same time, viewing risk through this lens enables us to craft new narratives, revealing its nature as a social construct that reinforces gender inequalities in the ways women are allowed to travel or restricted from doing so. Violence is a social phenomenon that shadows women’s lives constantly, whether on the move or at home. In other words, there is no truly safe place for us. But we will always have our own safety strategies.

The risk that women assume when crossing borders is a social construction informed by specific cultural contexts and the unequal power relations that shape them (Yang, 2017), perceptible as a process that reveals fresh nuances all the time. If traveling the roads of Latin America has been framed as a “dangerous activity” for women, this reflects an attempt, much like Massey (1994) suggests, to domesticate female bodies and impose limits on their mobility, both subjective and spatial. Although this construction unfolds largely on an ideological and subjective level, rooted in the impositions generated by gender inequalities and power relations, there is also a real danger that materializes in social phenomena present in the lived realities of women travelers. Acts of violence against women follow a historically shared pattern in the Latin American region. In the face of these threats, women travelers have developed a range of strategies to outmaneuver fear and danger.

Nonetheless, it is precisely in the lived experience of this “dangerous context,” in the spaces where strategies are produced along roads and borders, that new forms of resistance emerge, desestabilizing dominant conceptions of risk. This is a particular kind of resistance to fear as an imposition, a resistance that does not ignore the possibility of violence, but manages real risks often obscured by the supposed dangers used to blame women for the violence they suffer. Through this process, these women also create spaces to question imposed gender norms.

Latin America is considered one of the world’s most violent regions for women.6 News about gender-based violence is a regular feature in Brazilian media, though this phenomenon is not exclusive to the country. Violence against women and LGBTQIA+ people is all too frequent worldwide. According to some reports, Brazil is among the most dangerous countries for women travelers.7 Mexico and Brazil appear on the list of the ten countries with the highest rates of femicide.8 Yet it is important to emphasize that the violent structures of our societies, whether experienced firsthand or observed, reveal a “danger zone” for women that extends across much of the Global South. These zones are marked by the legacies of Western colonialism, contexts in which social inequalities and violence both reflect and are exacerbated by the historical brutality of colonization. To travel these routes, therefore, is to travel through the inequalities from which these places are constructed and, in this case, through the diverse forms of creativity and survival strategies of Latin American women.

Although women shape their lives through unique, singular experiences, there is something shared in being a woman in Latin America. The alarming rates of gender-based violence impact the lives of women from distinct racial and social class groups. A woman walking through cities like Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Cusco or Belém may face catcalls, inappropriate remarks, unwanted stares, and various forms of harassment that intensify their feelings of vulnerability.

National experiences and local realities play a role in shaping emotions, including the feelings of fear and the need for constant alertness that many women experience. However, the lessons learned from local experiences can also become protective techniques on the road. Furthermore, there is the knowledge developed through cultural and intersubjective encounters, including the exchange of ideas and symbols that circulate with women as they move across the region’s borders. Although these social inequalities affect Latin American women on a daily basis, here we choose to examine this social structure through the framework elaborated by Ortner (2007), seeking to understand the social coercion that articulates power relations at the level of lived, concrete experience, while simultaneously recognizing the margins of agency through which Latin American women negotiate their realities.

We argue that an over-emphasis on the power of structural conditions can distance us from real-world practices. While acknowledging that gender inequalities are specific to Latin American social structures and practices, we also recognize that “people always have at least some degree of ‘insight’ […] regarding the conditions of their domination” (Ortner, 2007:26). Júlia, a black woman and traveler, reveals this perceptiveness. She tells us: “violence follows us everywhere. I understand this violence […]; as a ‘black body’ I know I’m a target everywhere. So, I always try to be very cautious in such situations, keenly aware of everything, observing. But what always worries me more is the question of money, whether I have a place to sleep and eat, but you’re already observing, you’re constantly observing. It’s really a matter of survival”.

Amid an unequal, asymmetrical and violent social structure, women discover forms of resistance and action, challenging and creating fissures in this structure. Put otherwise, we can explore such inequalities in mobility through the subversive practices and agencies of transboundary subjects (Navia; Esguerra Muele; Padovani, 2020). A self-managed trip is far from being an irresponsible or naive act: it too is organized around the fear constructed within us. It is no act of madness. Traveling involves the kind of insight derived from recognizing women’s positions in the social world and simultaneously challenges the fixed roles and places assigned to them.

We fully recognize the alarming data on gender-based violence in the region, but question whether women are truly more vulnerable on the road than they are at home. Is the road really more dangerous? Júlia responds: “Danger is everywhere! We’re at home and something can happen. Marriage is a dangerous thing. […] There’s something I always say: is there anything more dangerous than marriage? Look at the femicide rates. Sometimes that dark street is less dangerous than being at home and married. Depending on the situation, you know? Because once you’ve left that [dark] street, you’re already somewhere else, you’re okay, you’re safe.” The idea of danger on the road is one variant of how violence against women is perceived, a theme woven into the ways in which women’s journeys through Latin America are constructed.

Confronting fear is part of the daily experience of the inhabitants of Latin American cities, spaces that are socially constructed as violent and unequal. From another perspective, lived experiences of violence can themselves become the motivation to embark on a journey. Such was the case for two of our interlocutors who saw travel as an alternative path, allowing them to escape violent relationships and life situations involving sexual harassment.

Our research shows that women develop specific intelligences to deal with “danger” on the road. Moreover, a process of learning and inventiveness unfolds as new borders are crossed. Assuming risk is also an essential part of the transformative experience of travel. Reflecting on the agencies that emerge in the journeys of Latin American women — in contexts of violent colonial continuities where lives and mobilities are constantly under threat — is one way of showing that, for women, borders are always zones of dispute.

Women on Latin American Borders

The routes taken by this research intersected with those of ten Latin American women travelers,9 with whom intersubjective interactions unfolded through distinct processes. Some of these involved physical encounters made possible by travel; others emerged from interactions in virtual spaces. These movements led to meetings on the road during two ethnographic journeys conducted in 2019/2020 and in 2022.

The first journey involved traveling through various South American countries. During the trip, I met Juana,10 a 31-year-old Argentine white lawyer who was undertaking “a different kind of voyage” on her own through the Salta region of Argentina. In Cusco, Peru, I encountered Liz, 23, Mexican, on her first solo trip; she had first flown alone to Ecuador, then continued to Peru. In Bolivia, in the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, I met Rosa (27) and Gabi (24), both street artists from Campinas, Brazil, who had embarked on the journey together, heading towards the Brazilian Pantanal and the Brazil–Bolivia border. The two friends traveled for a long stretch hitchhiking, stopping in city after city to manguear,11 selling craftwork and juggling at traffic lights.

In 2022, during another ethnographic journey, this time through the state of Bahia, I met Jak, 32, a Brazilian woman who was backpacking across Brazil with a male partner. We first connected through the topic of travel. She told me that, a few years back, in 2016, she had gone on a months-long backpacking trip with a female cousin that had taken them through several neighboring countries. During the same trip to Bahia, I also met Carol, 27, Argentine, a tourism specialist and circus (multi)artist who was thinking of “giving up traveling” after years on the road, a sharp contrast to when she started the path that would eventually lead her to Chapada Diamantina in Bahia, our meeting point in 2022. Both women had been living on the road for some time.

In addition to these ethnographic encounters on the road, others were made through an online network of travelers that formed via Instagram, based on the shared lived experience of being a traveler. Through this medium, I also interviewed Júlia (32), a black woman from Pará and a public worker. She is a seasonal traveler who backpacks during the breaks from her professional life, which ultimately pays for her trips. Nanda (32) and Flora (34), both white, are sisters from the state of Piauí, a physical therapist and a former bank worker respectively, who, in 2017, decided to quit their stable jobs and set off together on a backpacking trip that began in Colombia.

The trajectories of these women intertwine in the lines they each mapped out along the roads of Latin America. Their motivations and travel styles are diverse and personal, though not without commonalities. Latin America appears as a financially viable option within the context of global mobility. The securitization of European and North American borders, as well as linguistic differences, are among the main factors that tend to favor travel within the region. Liz chose South America because of the language. Initially, she had wanted to go to Canada, “but my English is terrible, so I went to these countries because of the language”. She felt people were kind to Mexicans, which also influenced her decision. There is a cultural component here too, especially when it comes to the diversity of encounters between alterities — between people who share a similar political and cultural history and among whom one recognizes oneself as part of a collective subject.

However, there is also the matter of financial resources. As Jak pointed out, the cost of a trip to Europe could fund a months-long backpacking trip across Latin America. When Jak first thought about traveling, encouraged by her mother, she considered going on a student exchange but could not picture herself on “one of those exchange programs in Canada or Dublin”, and lacked the money to do so anyway. She started searching for alternatives and stumbled on “videos of people backpacking across Latin America with little money”. She realized that travelers were able to get by with far less money compared to a trip to Europe: “…the cost of getting to Europe was sometimes equal to the cost of a whole backpacking trip across Latin America”. That was when she decided to “hit the road” with her cousin.

Other motivations shape these experiences, such as the desire to cross emotional and work-related boundaries. Quitting employment often marks a significant turning point in the construction of these journeys. In Lanna’s case, she had secured the job she had always imagined for herself, yet it was a male-dominated workplace that felt hostile to her presence. She “hated the fact of being a woman in that space”. Struggling to cope with a toxic work environment, she began to experience panic and anxiety. The harassment she endured affected her to the point that she wanted to flee her current reality and “experience other ways of living, another world, not that one which was hurting me so much”. That was when the idea took hold of quitting her job and setting out on a road trip. Nanda and Flora also reached a moment when they wanted to break away from the stressful work routine. Together, they left their jobs and began their backpacking journey.

Other forms of rupture become motivating factors too, like breakups. Juana left her job to begin traveling in a motorhome she had built with her then-boyfriend. After they broke up, she reorganized her plans and realized she no longer wanted a “boxed-in” life in Buenos Aires. She decided to continue traveling on her own. When Liz boarded a flight from Mexico City, she left behind a boyfriend who had given her an ultimatum: him or the trip. She chose not to forsake the journey she had been planning and for which she had been saving for so long.

Some ruptures are thus the result of choosing to hit the road, while others are what trigger the decision to travel. For Jak, a major turning point was the end of an abusive relationship in which she suffered both physical and emotional violence. After the breakup, she rethought the direction of her life and committed to the idea of undertaking a trip of her own. Nanda also used her trip as a process of self-reflection after the end of a long-term relationship. We can thus understand travel as a way for women to restore their well-being after experiencing sexual harassment or abusive relationships. So, hitting the road can also be a form of “risk avoidance”.

Breaking Through the Borders of Danger and Embracing Risk: “You’re Crazy!”

These conversations and shared experiences suggest that the very first border we cross when, as women, we plan a self-managed journey is the border of fear. What woman has never decided to go backpacking, especially without a male travel companion, and not received at least one insinuation of madness? Historically, the notion of “madness” has been employed as a tool to control and regulate the bodies of those women considered deviant.

Warnings about the dangers of the road, including rape and death, are forms of control instilled through fear, constructing “dangerous places” for women who are cast as vulnerable, even foolish, victims for deciding to set off “unprotected” —that is, without a male companion. Embracing the idea of madness becomes a way of resisting the domestication and immobilization of women’s bodies. This is exactly what the Argentine traveler Juana expresses when she tells us that she defied social norms and refused to find a male travel partner: “I’m not going to limit myself to doing only what makes me happy because I’m a woman; I’m not going to settle for a dull life, avoid risks just because I’m a woman”.

In our interlocutors’ testimonies, assuming the risk of being a woman traveler through Latin America means “having fear as a companion” – in other words, making fear one of the components of the journey. It is not simply a question of overcoming fear: rather, it is about “taking fear with you anyway. Because fear, I think, is part of who we are as women in society” (Lanna). The awareness of risk is constructed from local realities, and acceptable limits are deeply subjective perceptions. Taking risks was part of the researcher’s own experience, just as it was for the women in this study, though each perceived the perils of the road in her own way.

For Júlia, the perception of risk is linked to her place of origin. She explains that the neighborhood where she was born, a “dangerous” area of Belém, prepared her to face danger: “The thing about danger is: I live in a really dangerous place. I was born in a really dangerous place. I live in Sacramenta, right on the border with Barreiro, a place already marked by all kinds of dangers, it’s seriously dangerous, so much so that the neighborhood is known as ‘Sacrabala’ [Sacredbullet]. So for me, the hardest part is always having the money to get somewhere, you know?”. For Júlia, having money is a safety device. It is how she mitigates risk, how she handles basic precautions—even in places considered safe. “It’s like a basic precaution, you know? Watching who’s in front of you, who’s behind, being aware of the vibe. I think that where I live, the territory I inhabit, already makes me very alert. So in other places too, I stay alert, even if they’re considered safe” (Júlia).

The strategies that women develop in the context of violent urban everyday life, typical of many South American cities, sharpen multiple senses that help them face their fears. These senses guide women’s decisions about what clothes to wear, which routes to take, where to sit, among countless other everyday strategic choices designed to avoid the discomfort and vulnerability that comes with being a woman traveling through urban spaces. These learned practices are adapted on the road and become tools for staying safe on their journeys.

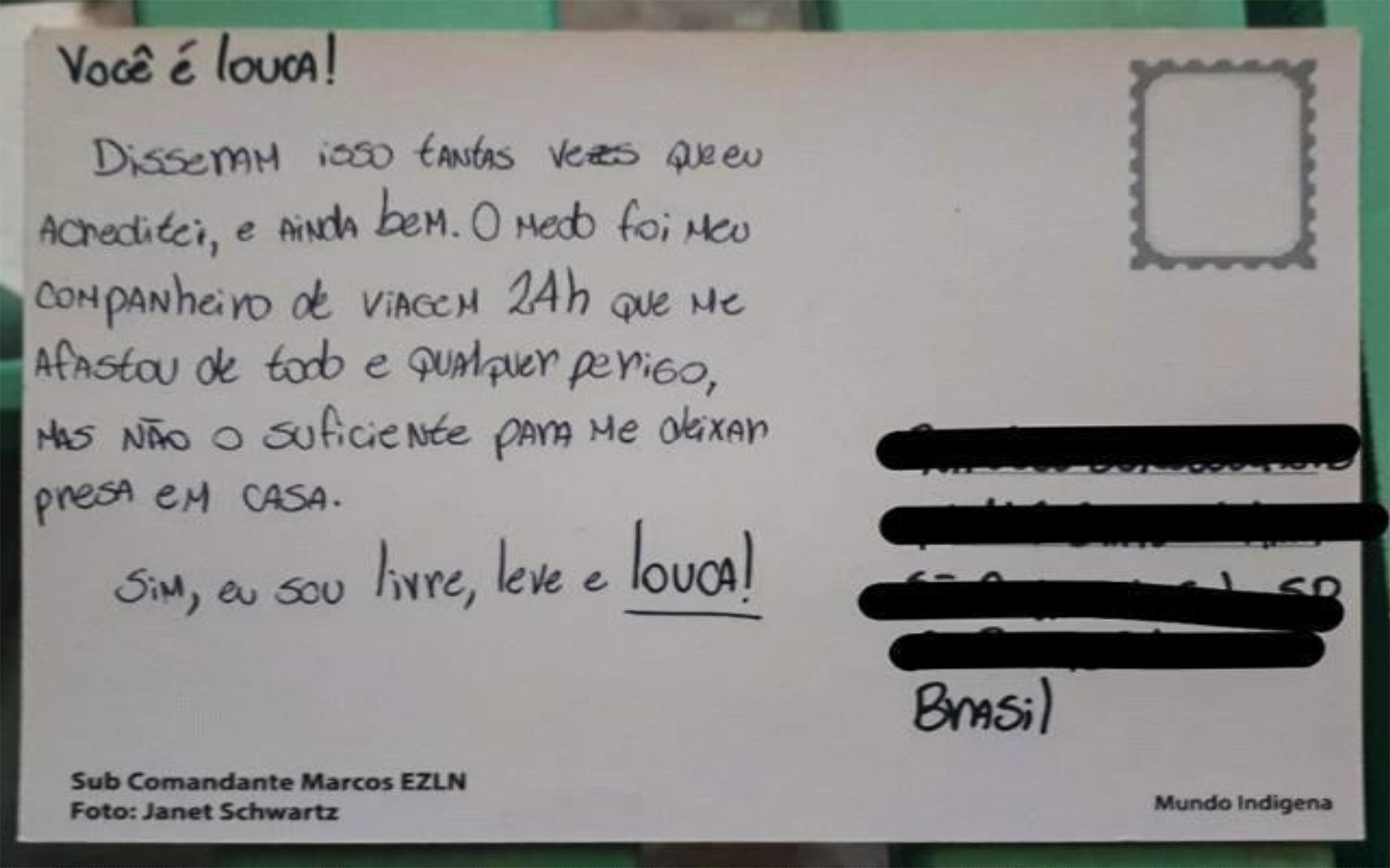

The above postcard helps us reflect on how Lanna negotiated her perception of risk. It was this very attitude that kept her “out of danger”. She believes that protective behaviors are already part of life for women living in Brazil’s major cities “I say: you’re already born with this chip, you already protect yourself just by being a woman living in Brazil—and I only discovered that on the road.” We can understand coping with risk on the road as something deeply related to the experience of being a woman who has lived the movements and codes of a Latin American metropolis. Perhaps what Lanna was saying is that this so-called “chip” with which we are born is nothing more than the daily learning necessary to survive the dangers of cities—and even small towns.

Lanna embraced fear as a limit, associating it with the risks we take every day: “it’s important to take the fear with you because fear is also what’s going to guide us in knowing our limits. So many girls say: I would never hitchhike! That’s okay! You don’t have to. Your fear warned you — that’s your limit”. In this sense, the strategy of keeping a sense of fear as a companion allowed her to stay alert and recognize the limits of places and herself, just as she wrote in the postcard above.

Flora told us that, at the beginning of her trip through Colombia with Nanda, they thought about giving up: “it’s such a heavy burden to be a woman traveling alone. Because it was always the same: — oh, you’re traveling alone? What do you mean? There are two of us! What do you mean alone?”. The harassing stares and inappropriate remarks during their walks through the streets of Barranquilla left them feeling frightened: “…we became scared, we thought we were going to be kidnapped at any moment”. It seems that the motive for the threats is women’s transgression of social conventions. The rupture with a relational identity (Oyhantçabal, 2018:96) — in other words, not being accompanied by a man — can provoke violent behavior towards a “defenseless” female body.

Women travelers have to deal with specific forms of violence in public spaces, including sexual harassment on public transport. Fear shows up in responses like being extra mindful of what time to leave and return, or simply in the act of walking down a dark street marking the edges of the city and the limits of safety. Some episodes of harassment surfaced during fieldwork, such as at bars in Cusco that I visited with Liz. In these spaces, it became evident how the bodies of unaccompanied women are perceived essentially as open invitations for all kinds of advances. Many men offered drinks and their company, some in ways that were pushy or clearly inappropriate. As Nanda put it: “the whole trip was like that. We experienced a lot of harassment. Eventually, there came a point where we just didn’t feel safe anymore.”

Flora would activate her “full defense mode” whenever she felt vulnerable. One of her strategies was drinking alcohol with moderation, even though she also believes it is necessary to “let things flow with the universe”. She believes that “when I commit to a trip, I don’t go in with fear, because if you go in with fear, shit happens. You attract it, you end up drawing something bad towards you”. But, of course, “you have to be careful”. Perhaps what Flora is trying to say is that although precautions are necessary, it is important not to close oneself off from encounters along the way. In other words, you have to trust in the road’s own dynamic. Liz’s perception of insecurity was different. The violent everyday reality of Mexico City made her feel safer in Cusco.

Learning, Agency, and Strategy: Managing Risk

Backpacking is shaped by specific strategies for life on the road. These emerge from lessons learned in intersubjective encounters with other women, who act as “teachers” by sharing tips about spatial limits, modes of transportation, strategies for finding accommodation, and more. These codes and rules are transmitted through experience and conversation. The narratives of the interlocutors frequently mentioned their fears, accompanied by strategies to elude harassment. Examples include the use of services and products specifically aimed at women: female-only dorms, which are now common in many hostels; controlled or limited outings at night; and setting boundaries in interactions with men.

There are specific codes and rules for women travelers on the road: places to avoid visiting alone, times deemed unsafe for arrivals, car rides that should not be accepted. Learning these strategies helps deconstruct fears. This deconstruction is achieved through: a) detailed planning, which involves negotiation, agency and the self-management of resources; b) appropriation of digital tools and technologies; c) prior knowledge of localities and border zone dynamics; and d) the ability to improvise.

Along these lines, women develop particular intelligences to cope with “danger” on the road. There is a continual process of learning and inventing solutions that unfolds as new borders are crossed. Confronting risk becomes a vital part of the transformative experience involved in this kind of travel. Yang (2017) defines risk as “A socially constructed consciousness of danger or mostly undesirable outcomes, though excitement and opportunity can be derived from the outcomes” (2017:21). The awareness of danger creates space for agency, and this agency, in turn, opens up future paths. This is precisely what keeps women from being easy targets.

Beatriz Sarlo (2015) argues that, in planning a trip, we mentally trace out ways of experiencing places in advance. However, planning does not guarantee organization: there are always disorganized zones and unpredictable spaces. In the lexicon of Brazilian travelers, these moments that evade control and often lead to changes in itinerary are known as perrengues. This term refers to unexpected difficulties, events travelers already know may (and probably will) happen and that are sometimes even keenly anticipated. It is often through the perrengue that the traveler learns to negotiate risk and improvise. The perrengue disrupts pre-established plans and reveals the potential for action, invention and creativity. It shapes subjective experience and generates accumulated learning.

Rosa set off on her trip already improvising. She had no money and planned to learn and work as she traveled: “I had to support myself somehow, and since I didn’t know how to make craftwork or anything else, I started learning to juggle”, she said. She traveled by making money as she went, working in various towns and cities each day in the company of a friend. Gabi functioned as a facilitator through established modes of negotiating reality. Both women are mothers and had arranged their family responsibilities before the trip. Rosa trusted her friend, who had accumulated experience and strategies for managing travel, and wanted to learn by sharing life on the road with her. Companionship was also key for Nanda, who trusted her sister Flora and relied on her experience. Learning happens throughout the journey, often through other womens’ experiences. It is in these intersubjective encounters that knowledge circulates, especially between those who are just beginning their travels and others already familiar with the rhythms and movements on the road.

In the case of Rosa and Gabi, agency began to emerge during the planning stage where the main negotiations revolved around motherhood — that is, ensuring a family support network that could help care for their children. Disconnecting from emotional and family ties, whether temporarily or for a longer period, requires a negotiation process and the construction of new bonds, now managed from a distance. For other interlocutors, financial organization was the top priority: saving up some money and planning an itinerary. Relationships on the road are negotiated on each woman’s own terms. Even so, there is a chain of agency that involves hitchhiking, contact networks, accommodation options and other dimensions. It is also collective.

These capacities for agency surface as part of a transformative dimension generated through lived experience, producing multiple meanings in the act of traveling. “Hitting the road” involves perrengues and hardships that are part of the adventure of embarking towards the unknown and the unstable. Difficult situations often stimulate creative solutions and open up space for practices of agency that make it possible for them to be negotiated. Within the diverse self-management strategies, decisions about “where to stay” and “how to get around” are central, since they directly involve the creation and management of resources during the journey. Many of the creative solutions developed by Latin American women travelers stem from the types of work they engage in to sustain life on the road.

Planning ahead includes actions like “saving money”, looking for volunteer work, booking hostels, registering on platforms, making spreadsheets, and other logistics. Prior contact with hostels, using platforms like WorldPackers, CouchSurfing and Booking.com, is common to arrange volunteering gigs and find accommodation. The use of apps and networking platforms shapes the travel routes of our interlocutors, demonstrating how the construction of a journey takes place in virtual communities and spontaneously built solidarity networks. Juana remarked that the year before she decided to live on the road was “a year of planning, organizing, saving money, researching places, hostels, volunteering”. Juana, Liz, Flora and Nanda all adopted strategies to save money, as well as reaching out early to potential volunteer hosts.

The way a trip is organized relates to the perception of risk, but is also influenced by class positions. These two dimensions are deeply entangled. Proximity to, or distance from, everyday experiences of violence can shape women’s perception of risk in diverse ways. The solutions used to navigate dangerous borders on the road are highly individual and risk management is a personal affair. Even so, collective forms of agency are also developed, such as shared strategies to keep a distance from men perceived as sexist or harassing. For most of the women interviewed, planning helped generate a sense of safety.

Travelers who choose to organize their trips with an emphasis on “safety” often allocate financial resources accordingly. There is a “predisposition among some women to choose certain destinations based more on the safety of the environment than on their own personal fears or insecurities” (Reis, 2016: 79). Liz considered safety strategies to be fundamental. Hence she chose to travel by bus and stay in hostels as her way of staying safe. From her viewpoint, there are certain situations that create potential vulnerability, such as hitchhiking or accepting hospitality from men under the guise of solidarity.

Seen in this light, prior planning appears as a safety tool, even if the itinerary does not end up being followed in full. “I love planning, but I found out on the road that I hate sticking to my plans. I’d get to a city and ask: what’s there to do here? Where should I go next?”. Lanna continues: “It’s totally fine to plan, because we need to feel that sense of security, to know at least a little about a place before going, it helps soothe our fears, the fear of the unknown. So when you already know a bit, it calms you down. That’s good. But the bad part is locking yourself into a rigid itinerary.” In her comments, it becomes clear that building an itinerary does not have to mean rigid planning. It is important to learn about future destinations to ease one’s fears, but one must also trust the universe, and follow the buena vibra.

Unlike the interlocutors who organized their trips using their existing financial resources, the street artists sustain themselves as their journey unfolds, revealing distinct class positions. They are more exposed to the dynamics of streets, plazas and the precarities of travel. For them, the sense of belonging to a group is of central importance and provides a degree of spatial mobility. Their itineraries are shaped by limited financial means and are realized through daily negotiations within networks of information, connections and solidarity. These kinds of journeys also rely on the manual and intellectual skills learnt and developed by the travelers as they go. Improvisation is always present.

Objects and tools play a defining role in the cross-border experiences of these women. Liz began her journey with a rolling suitcase and returned home with a backpack bought in Ecuador, where she abandoned her suitcase. Rosa set off with a huge suitcase which gradually shrank during the return journey. Carol re-signified her baggage throughout the trip, but like Gabi, carried juggling props and tools for making craftworks.

Today, there are strategic tools that support travel, like access to location services. Internet connectivity enables the use of various apps that make travel easier and is crucial for sharing updates and photos with friends and family. Most establishments, like hostels and restaurants, offer Wi-Fi. The use of mobile phones and other digital technologies is essential for arranging accommodation, checking maps, figuring out transport services, and so on. Beyond that, “providing updates” to others is part of the ongoing negotiation involved in traveling.

There is also a need for prior knowledge of border dynamics and their mechanisms of control — information that is then expanded through lived experiences on the road. It is important to know which documents are required for entering each country. Bolivia, for instance, still requires proof of yellow fever vaccination upon entry. Personal documents thus become essential elements in planning, especially for international travel, and may — or may not — be required, depending on the country. In the contemporary South American context, citizens of Mercosur nations can travel between the zone’s countries using a national ID card for border checks. Additionally, the passport remains a widely accepted document. The documents required are shaped by political and public health conditions, as circulation rules are subject to change. Knowledge about border zone processes is thus a key travel strategy.

The women in this research built their itineraries across different time frames, crossing multiple national and cultural borders. They embraced risk, facing uncertainty and the unexpected, and used strategies that ranged from aesthetic transformation to alternative ways of navigating time and space in order to manage risk. They overcame fear by relying on organizational methods that shaped the kind of work they would do, how they would move, and other defining elements of their travel itineraries. We can identify other factors that influence the organization and realization of each traveler’s personal logic of movement to demonstrate how “hitting the road” does not mean acting without a plan: on the contrary, it is a planned, agency-based and managed action that gradually becomes a viable, consolidated project.

Travel as an Individual Project: Deconstructing Risk

Two types of travel projects emerged from the fieldwork: those pursued solo and those undertaken in the company of another woman. The nature of these projects is shaped by both individual and collective strategies that influence different travel styles. In terms of meaning, solo travel holds strong symbolic weight in the narratives of many women travelers, sometimes creating an idealized image that feels out of reach for other women. Lanna offers a grounded reminder: “It’s okay not to like traveling alone. Women who travel solo aren’t better than anyone else, they’re not more of a woman, or braver than anyone, it’s just one way, one lifestyle, and a tool for self-discovery. It’s not a formula for self-discovery.” In other words, for her, traveling alone is a process, not an absolute symbol of courage.

For some women, the company of another woman is essential. Jak felt stronger traveling with her cousin and noticed how the way local men approached her changed depending on whether she was with her or when they joined groups of men. She said: “because I’m a woman, I felt this powerful bond between us, when we went through stuff together or apart, we would later talk about any kind of discrimination, if either of us had gone through some form of sexism”. Even so, Jak also undertook solo itineraries.

For Flora and Nanda, traveling together was a way of strengthening their bond as sisters, sharing projects, desires and worldviews. It was about seeking a mutual understanding through lived experience on the road. Still, this did not make them immune to the effects of machismo: “…it’s exhausting to be a woman on the road because you’re afraid all the time”. Nanda adds: “I remember wanting to walk alone at night. I still remember that feeling of being in this deserted place, a tiny fishing village, a paradise, and I didn’t feel safe walking on the beach, just because I was alone”. Clearly, sharing a journey with another woman does not erase fear or eliminate feelings of insecurity.

Some of the interlocutors’ itineraries revealed a shared yet autonomous project, allowing space for both individual freedoms and the sharing of experiences, including their fears. This suggests that the collective dimension is crucial to shaping women’s journeys. The ability to alternate or choose travel companions highlights how subjectivity is shaped by the ways women construct their own projects by discovering their capacity to surpass limits and make independent choices.

In this process of constructing and deconstructing the journey, reflections on oneself and one’s life choices emerge. Transgressing established norms invites the questioning of the social logic of relational travel. Along the way, there is an exchange of signs and degrees of encouragement. Júlia began her travels always in the company of someone else, but with experience, she acquired the confidence to take flight alone, no longer dependent on company or a male presence to travel.

Carol told us that her initial motivation came from the idea of group travel. She first set out with a group of friends, but as the journey progressed, the meaning of travel acquired new dimensions for her. The possibilities for movement expanded. Until the moment came when she saw that, even when she was with someone, she was doing the rolés (trips) alone. That was when she understood that traveling solo was less dangerous than it seemed. This process of gaining confidence was part of the trajectory that inspired the present research. It mirrors the first backpacking experience of one of the article’s authors, a trip undertaken in 2011 that began as a part of a group, but where, halfway through, she found herself alone on a bus from Cusco to La Paz, formulating her own itinerary.

The imagined “seven-headed monster” of solo travel begins to dissolve through movement, opening doors to new ways of experiencing the road. As Flora explained: “after I gave it a name, I realized it’s really not a seven-headed monster, unlike when I first started traveling […]. These days I even prefer to travel alone. I don’t know why. I guess you end up being more open to meeting people, having conversations, connecting with others […]. When you’re alone, you’ve got to figure it out, and that’s a kind of learning too, a kind of independence”. Her testimony suggests that positive perceptions of solo travel gradually emerge as women discover advantages to the practice that help deconstruct risk.

Crossing borders alone becomes an exercise in valuing autonomy, albeit each woman in her own way. As Lanna said: “It’s not a recipe for happiness”. Engaging in an individual travel project means self-managing a route that requires care, but one that “is much more than what you expect and much less than what you fear”, as Juana put it. Fear is often built through exaggerated projections of what might happen. Meanwhile, the lived experience can be enjoyable, even liberating, surpassing anticipated causes of anxiety.

Even though solo travel appears as a central theme in the journeys of many women, collective elements are never absent: they are part of the individual dynamics. Jak, for example, recently mentioned being on a shared travel project with her partner, as was the case in many of Carol’s trips. Lanna, too, alternates between traveling with others and on her own. These cases show that the shift between solo and shared journeys does not diminish the traveler’s agency or her personal ways of making travel meaningful.

The itineraries of these women allow us to analyze the both the spatial and subjective dimensions of their paths. Confronting the risk of travel allows a formulation of the subjective aspects of borders, which become spaces of possibility and the construction of subjectivity, as Gloria Anzaldúa (2012) suggests. These journeys involve agency, organization, learning and self-reflection. The diverse waypoints of these routes tell us which borders they have crossed — lines traced through improvisation, each woman with her tools and strategies, making her way by walking.

The cultural displacements that shape the subjectivities of Latin American women travelers reflect the different ways in which they position themselves to cross the borders dividing worlds and people. At the same time, they offer contributions to challenge dominant gender norms imposed at these borders. It is in the act of travel, in lived experience, on the road itself, that strategies are built to expand possibilities for mobility, undoing gendered constraints and destabilizing dominant notions of risk.

If anthropology can help us find paths amid the ruins of this world we inhabit, as Ingold (2019) suggests, then we can say that women travelers are claiming a place in the formation of Latin America. They produce subjectivities that move through the margins of modern individualist logic. These women share their presence and learn through each other’s experiences. In other words, they create themselves and one another through the experience of travel, a form of resistance that defies border rules and enables other realities to be experienced. They help us imagine a possible world among the ruins of a modernity invested in controlling women’s bodies, a modernity that now collides with the historical courage and organization of Latin American women.

References

-

ABU-LUGHOD, Lila. Locating Ethnography. Ethnography 1(2), p. 261-267. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1177/14661380022230

» https://doi.org/10.1177/14661380022230 -

AMANTE, Maria de Fátima. Das fronteiras como espaço de construção e contestação identitária às questões da segurança. Etnográfica, v. 18, p. 415-424, 2014. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/etnografica.3770

» https://doi.org/10.4000/etnografica.3770 - ANZALDÚA, Gloria. Borderlands/La frontera: the new mestiza. 4 Ed. San Francisco: Aunte Lute Books, 2012.

- CORRÊA, Ester Paixão. Mulheres na estrada: encontros etnográficos nas rotas da América do Sul. 2022.Tese (Doutorado em Antropologia Social) - Centro de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), Natal, 2022.

-

FAULHABER, Priscila. A fronteira na Antropologia Social: as diferentes faces de um problema. BIB - Revista Brasileira de Informação Bibliográfica em Ciências Sociais, n. 51, p. 105-125, 2001. Disponível em: https://bibanpocs.emnuvens.com.br/revista/article/view/236 Acesso em: 15 set. 2025.

» https://bibanpocs.emnuvens.com.br/revista/article/view/236 -

FONSECA, Cláudia. O anonimato e o texto antropológico: Dilemas éticos e políticos da etnografia 'em casa'. Teoria e Cultura, v. 2, n. 1 e 2, p.39-53, 2007. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufjf.br/index.php/TeoriaeCultura/article/view/12109/6341 Acesso em: 01 mai. 2024.

» https://periodicos.ufjf.br/index.php/TeoriaeCultura/article/view/12109/6341 - GONZALEZ, Lélia. Por um Feminismo Afro-Latino-Americano: Ensaios, Intervenções e Diálogos. Rio Janeiro: Zahar, 2020.

- INGOLD, Tim. Antropologia para que serve ? Rio de Janeiro: Editora Vozes, 2019.

-

KAMINSKI, Leon; VIEIRA, Danusa. Rosa dos ventos no peito: mulheres, viagens e contracultura. Equatorial - Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia Social, v. 7, n. 12, p. 1-29, 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21680/2446-5674.2020v7n12ID18614

» https://doi.org/10.21680/2446-5674.2020v7n12ID18614 -

LUGONES, Maria. Colonialidad y género. Tabula Rasa. n. 9, p. 73-102, 2008. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1794-24892008000200006&lng=en&nrm=iso> Acesso em: 15 set. 2022.

» http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1794-24892008000200006&lng=en&nrm=iso> - MASSEY, Doreen. Space, place, and gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994.

- MASSEY, Doreen. Pelo espaço: uma nova política da espacialidade. Trad. Hilda Pareto Maciel e Rogério Haesbaert. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 2008.

- MCCLINTOCK, Anne. Couro imperial: raça, gênero e sexualidade no embate colonial. Trad. Plínio Dentzien. Campinas: Editora da Unicamp, 2010.

- NAVIA, Angela F.; ESGUERRA MUELLE, Camila.; PADOVANI, Natália C. Mobilidades e fronteiras: perspectivas antropológicas feministas para uma mirada interseccional. Vivência: Revista de Antropologia, v. 1, n. 56, p. 13-20, 2020. DOI: 10.21680/2238-6009.2020v1n56ID23675.

-

OYHANTÇABAL, Laura M. Cuando el viaje se siente en el cuerpo: Algunas reflexiones sobre viajes, nomadismo y género. Encuentros Latinoamericanos, v. II, nº 2, p. 86-109, 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.59999/2.2.125

» https://doi.org/10.59999/2.2.125 - ORTNER, Sherry. Poder e projetos: reflexões sobre a agência. In: GROSSI, Miriam, Pillar et al. (Orgs.). Conferências e diálogos: saberes e práticas antropológicas. Blumenau: Nova Letra, p. 45-80, 2007.

-

PISCITELLI, Adriana "#queroviajarsozinhasemmedo": novos registros das articulações entre gênero, sexualidade e violência no Brasil. cadernos pagu (50), Campinas, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/18094449201700500008

» https://doi.org/10.1590/18094449201700500008 - REIS, Alana. Mulheres e viagens: insegurança e medo? Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso - Faculdade de Turismo e Hotelaria, Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF), Niterói, 2016.

- SARLO, Beatriz. Viagens - da Amazônia às Malvinas. E-galaxia. E-book. 2015.

- YANG, Elaine C. L. Risk-taking on her lonely planet: Exploring the risk experiences of Asian solo female travellers. Doctoral dissertation, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia, 2017.

- XAVIER, Ângela Leite. Olhos de Estrela: Chaskañawi. Ouro Preto: Edição da autora, 2011.

-

1

“Backpack” is a polysemic term. In this context, the noun refers to the cargo bag as a physical object — a large, heavy-duty fabric sack used for travel as a verb or gerund, “backpacking” also designates a mode of travel shaped by the norms and practices of the backpacker subculture.

-

2

The “attack backpack” is a smaller piece of gear used to carry essential and valuable items, providing support during specific segments of the journey.

-

3

The presence of women in the world of travel and the ways in which their movements are represented have been a topic of debate across various academic approaches, especially those engaged in deconstructing colonial narratives. One central argument emphasizes the need to analyze processes of colonization through the lens of power and gender theories, as a way to account for the inherent complexities and the differentiated experiences of men and women in contexts of mobility (McClintock, 2010).

-

4

Fieldwork was conducted by the first author, Ester Corrêa. For this reason, we alternate between first-person singular and first-person plural narration throughout the text.

- 5

-

6

According to UN Women Brazil (2017), Latin America and the Caribbean are globally the most violent regions for women. See: http://www.onumulheres.org.br/noticias/regiao-da-america-latina-e-do-caribe-e-a-mais-violenta-do-mundo-para-as-mulheres-diz-onu/

-

7

A ranked list published in 2019 by a travel security agency — the Women’s Danger Index — has circulated on various news websites. However, the lack of data produced by more reliable agencies and observatories highlights the need for greater attention to this issue. In early 2024, following the murder of Julieta Hernandez in Brazil, the debate around this topic resurfaced with renewed intensity. A number of women’s perspectives can be found at: https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2024/01/12/o-problema-nao-e-viajar-e-ser-mulher-viajantes-solo-associam-violencia-ao-machismo

-

8

Source: ECLAC, Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean. See: https://oig.cepal.org/es/indicadores/feminicidio

-

9

We use the category traveler to refer to women who organize self-managed itineraries, distinguishing them from tourists, whose trips are typically structured and mediated by external agents.

-

10

The names of the interlocutors appear in accordance with prior discussions with the authors regarding anonymity, following the suggestions of Fonseca (2007). Most women chose to use their real names or abbreviated forms.

-

11

Mangueio is a practice commonly used by street artists when selling their work, typically employing various forms of persuasion and proactive engagement.

Edited by

-

Editors responsible for the evaluation process:

Natália Corazza Padovani,Julian Simões,Luciana Camargo Bueno.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

14 Nov 2025 -

Date of issue

Oct 2025

History

-

Received

24 May 2024 -

Accepted

24 Apr 2025

Dangerous Borders: An Ethnography of Women Traveling in Latin America

Dangerous Borders: An Ethnography of Women Traveling in Latin America

Source: Interlocutor’s personal archive.

Source: Interlocutor’s personal archive.