ABSTRACT

Nitrogen (N) is a key factor for achieving high grain yield in irrigated rice, and remote sensing tools, such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), can support optimization of N application during the growing season. This study aimed to evaluate the use of NDVI for estimating biomass, shoot N accumulation, and grain yield, as well as to assess its potential for guiding N fertilization in rice. Field experiments were conducted in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, during the 2021/22 and 2022/23 growing seasons, using the genotype IRGA 424 RI and five N fertilization levels. NDVI, measured throughout the crop cycle, detected differences in plant growth associated with N availability. Strong relationships were observed between NDVI values and the evaluated parameters, indicating that the index can predict plant N status and estimate crop yield. Based on NDVI readings obtained with a proximal vegetation sensor (GreenSeeker), a model was developed to classify crop biophysical parameters and to guide site-specific N fertilization during the growing season.

KEYWORDS

biomass; grain yield; remote sensing; nutritional status

INTRODUCTION

Nitrogen (N) is the most important nutrient for increasing grain yield and maximizing yield components in irrigated rice (An et al., 2018). Despite its crucial role to plants, N is among the most difficult nutrients to manage efficiently in agriculture (Amaral et al., 2015). Nitrogen fertilization in irrigated rice is generally based on a few indicators, which may provide low precision because they consider only soil supply and expected crop response to fertilization (Reunião Técnica da Cultura do Arroz Irrigado, 2022). These indicators do not account for the N status of the crop during development or the spatial variability of N supply within the field. As a result, a single topdressing nitrogen rate is applied, benefiting some areas, while others receive excessive or insufficient amounts. This practice reduces yield (Yinyan et al., 2023), raises production costs, and increases the risk of N losses and environmental contamination (Padilla et al., 2018).

Since plant N requirements vary throughout growth and development, it is essential to determine nutrient levels at specific developmental stages (Ata-Ul-Karim et al., 2017; Taiz et al., 2017). Moreover, application rates must be adjusted to match crop demand in different parts of the field, considering soil N availability and plant nutritional status over time (Poletto, 2004; Zhang et al., 2021). Remote sensing techniques can support these decisions by providing additional information for fertilization recommendations (Kanke et al., 2016). Sensors detect the spectral characteristics of the canopy during the crop cycle, serving as indirect indicators of crop nutritional status and yield potential (Queiroz et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2022).

Two spectral regions are directly related to plant biophysical traits and grain yield, namely red (R) and near-infrared (NIR). Greater biomass increases canopy reflectance in the NIR, while higher chlorophyll content reduces reflectance in the red spectrum (Figueiredo, 2005). To minimize variability caused by external factors, these measurements are expressed as vegetation indices. Among them, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) (Rouse et al., 1974) is one of the most widely used in agriculture (Singh et al., 2015). NDVI values range from –1 to +1; higher differences between NIR and red reflectance yield higher NDVI values, indicating greater biomass and chlorophyll content and, consequently, higher grain yield potential.

Based on this context, this study aimed to monitor rice growth using NDVI and to evaluate its relationship with crop N status through biophysical parameters and grain yield. A further objective was to develop methods for optimizing N application rates during the growing season according to the actual needs of the plants.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Field experiments were conducted during the 2021/22 and 2022/23 growing seasons in Cachoeirinha, Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil (29°55′30″ S, 50°58′21″ W) (Figure 1).

Soil and climate characteristics

Cachoeirinha is located in the physiographic region of the Central Depression of Rio Grande do Sul State (RS). The soil in the experimental area is classified as a typical dystrophic Haplic Gleysol, according to SiBCS (Santos et al., 2013), and the climate is humid subtropical (Cfa), with average annual rainfall of 1,470 mm and mean air temperature of 19.6 °C. Figures 2a and 2b present meteorological data on rainfall, solar radiation, and air temperature for the study period.

Rainfall (a), solar radiation (a), and average maximum and minimum air temperatures (b) in the study area during the 2021/22 and 2022/23 growing seasons.

During the 2021/22 growing season, mean air temperature from October to March was 24.2 °C, with average maximum and minimum values of 29.7 °C and 18.8 °C, respectively. Rainfall totaled 527.2 mm in this period. In the 2022/23 growing season, mean temperature was 24.0 °C, with maximum and minimum averages of 29.4 °C and 18.7 °C, respectively.

Although average temperatures were similar in both seasons, 2022/23 had cooler nights (Figure 2b). It was also a drier year, with lower cumulative rainfall, especially between October and November (Figure 2a), totaling 407.8 mm compared with 527.0 mm in 2021/22. Despite reduced rainfall, average solar radiation in 2022/23 (19.85 MJ m⁻2) was lower than in the first season (22.26 MJ m⁻2) (Figure 2a).

Description of treatments and parameters evaluated

The experiment followed a randomized complete block design with four replicates. Each plot consisted of nine 7-m rows spaced 0.17 m apart, totaling 10.70 m2. The cultivar IRGA 424 RI, currently the most widely grown in Rio Grande do Sul State, was used. Treatments included five nitrogen rates applied as topdressing (0, 60, 120, 180, and 240 kg N ha⁻1). Applications were split between the V3 stage - three fully expanded leaves (2/3 of the total N rate) and the V8 stage - eight fully expanded leaves (1/3 of the total N rate), to ensure maximum N availability before panicle formation. Urea (45% N) was used as the N source. Nitrogen rates were selected to generate growth variability throughout the crop cycle, enabling the evaluation of differences in N status. Phosphorus and potassium fertilization consisted of 64 kg ha⁻1 P₂O₅ and 102 kg ha⁻1 K₂O at sowing.

In 2021/22, rice was sown on October 11 with emergence on October 26, while in 2022/23, sowing took place on October 18 with emergence on October 29. In both seasons, sowing density was 105 kg ha⁻1 under minimum tillage, with seeding performed 30 days after desiccation of volunteer plants.

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) was measured at the V5 (five fully expanded leaves), V6 (six fully expanded leaves), V7 (seven fully expanded leaves), V8 (eight fully expanded leaves), V9 (nine fully expanded leaves), and R0 (panicle initiation) stages using the GreenSeeker® active canopy sensor (Trimble, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Measurements were taken within the central rows of each plot with the sensor positioned parallel to the rows at 0.8 m above the canopy. NDVI was calculated as Rouse et al. (1974):

Wherein:

R is red reflectance (680 ± 10 nm), and

NIR is near-infrared reflectance (770 ± 15 nm).

To assess NDVI progression under different N rates, the Area Under the NDVI Progress Curve (AUNPC) was calculated from sequential NDVI readings, providing a single value per treatment. This procedure is traditionally applied in plant pathology to quantify disease progress (Amorim, 1995), being a robust quantitative epidemiological parameter. Calculations were performed in R Studio (version 4.1.1) using the Bolstad package (2009), which applies Simpson’s rule for integration. AUNPC values were then correlated with grain yield, obtained from the harvested net plot area (1.7 m2), consisting of five central rows, each 2 m long, after border rows were excluded. After threshing, the grain mass was weighed, adjusted to 140 g kg⁻1 moisture, and extrapolated to kg ha⁻1.

Biophysical parameters were also assessed. At V8, prior to the second N topdressing, aboveground biomass and accumulated N were determined. Aboveground dry biomass was obtained by sampling plants on three 0.5-m rows (0.25 m2), then oven-dried at 65 °C until constant weight, and weighed. Total N concentration in plant tissue was determined by the semi-micro Kjeldahl method (Tedesco et al., 1995). Accumulated N in the aboveground biomass (kg ha⁻1) was calculated by multiplying tissue N concentration by dry biomass yield. Both biomass and shoot N accumulation were correlated with NDVI measured at the same growth stage for both growing seasons studied individually, using NDVI as the independent variable and biomass or shoot N accumulation as dependent variables.

To enable single regression analysis across both experimental years, NDVI, aboveground dry biomass, and accumulated N values were normalized. Normalization was performed by dividing the absolute value of each treatment by the mean value of the variable in each experiment. This procedure is equivalent to the normalized grain yield method proposed by Vian et al. (2018) and Molin (2002) for comparing spatial variability of grain yield within a given area. Normalized data (NOR) were expressed as percentages and calculated according to [eq. (2)]:

Wherein:

VA is the absolute value of the analyzed variable, and

VM is the mean value of the variable in the experiment considering all treatments.

Normalized values were used to generate a single regression curve, from which critical values were determined and used to classify crop development according to response to N rates. The classes were defined as: low (<90% of the mean), medium (90–110% of the mean), and high (>110% of the mean) (Vian et al., 2018; Molin, 2002).

Before regression analysis, data were screened for outliers, and residuals were tested for normality and homogeneity of variances. All assumptions of parametric analysis were met. The data were then subjected to analysis of variance using the F-test (p ≤ 0.05) in R Studio (version 4.1.1). Regression analyses were performed using SigmaPlot (version 14.0).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) dynamics throughout the cycle

Significant variation in NDVI among N rates and growth stages indicated that N availability strongly affected irrigated rice growth during the crop cycle. Figure 3 highlights the NDVI patterns for the 2021/22 and 2022/23 seasons. These variations resulted from differences in shoot biomass accumulation and tissue N content (Li et al., 2020) as influenced by N rates.

Temporal dynamics of the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) as a function of days after emergence (DAE) and nitrogen availability during the 2021/22 (a) and 2022/23 (b) growing seasons. Arrows indicate the timing of nitrogen topdressing; bars represent the standard error of the mean. Lowercase letters denote mean comparisons at the 5% significance level within each assessment date. ns = not significant.

Greater N availability increases biomass production and chlorophyll content (Cao et al., 2017). Accordingly, higher biomass enhanced reflectance in the near-infrared (NIR) region, while greater chlorophyll reduces reflectance in the red spectrum (Serrano et al., 2000), thereby increasing NDVI values.

NDVI values increased across all treatments as plant development advanced. The smallest increases occurred in treatments with no N or with the lowest rate (60 kg N ha⁻1), while the highest increases occurred in treatments with higher rates. These differences reflect the effect of N supply on plant N uptake and subsequent canopy development (Singh et al., 2015). Similar patterns have been reported in rice experiments worldwide. Rehman et al. (2019) observed NDVI values ranging from 0.15 to 0.58 for minimum values and from 0.72 to 0.82 for maximum values across different environments. In their study, NDVI increased with higher N application until reaching a plateau, with low N rates producing lower NDVI values and high N rates producing higher values. Kanke et al. (2016) and Padhan et al. (2023) also reported that NDVI values rose with increasing N fertilization.

In 2022/23, NDVI declined around the V8 stage (eight fully expanded leaves, 47 DAE) across all treatments, except for the no N treatment, which showed this decline earlier at the V7 stage (40 DAE) (Figure 3b). This decrease demonstrates NDVI sensitivity to plant stress (Figueiredo, 2005). In this growing season, irrigation management was hampered by low rainfall at some spots (Figure 2a), which reduced water layer in the experimental area between 40 and 75 DAE. Fluctuating water levels not only induced plant water stress but also promoted nutrient losses, particularly N (Knoblauch et al., 2012). Combined with reduced solar radiation availability (Figure 2a), these factors further limited N assimilation (Taiz et al., 2017). In addition, episodes of cold night winds caused leaf-tip chlorosis, altering radiation reflection and absorption (Figueiredo, 2005). Duan et al. (2021) likewise reported that NDVI values varied across years and locations with different climates, reflecting biomass and N accumulation dynamics that influence canopy reflectance.

Grain yield estimation by NDVI

NDVI values at individual growth stages may not provide accurate estimates of grain yield, since crop growth and production potential are influenced by multiple factors at different stages (Baral et al., 2021). Thus, assessing NDVI at several points in the cycle is crucial for reliable grain yield estimation. Lu et al. (2022) identified crop growth stage and N fertilization as the main agronomic factors affecting N status indicators, followed by environmental factors such as climate and soil. For greater accuracy, NDVI should be measured at three or more stages for a precise estimation of the nutritional status, and integrating these values further improves predictive power.

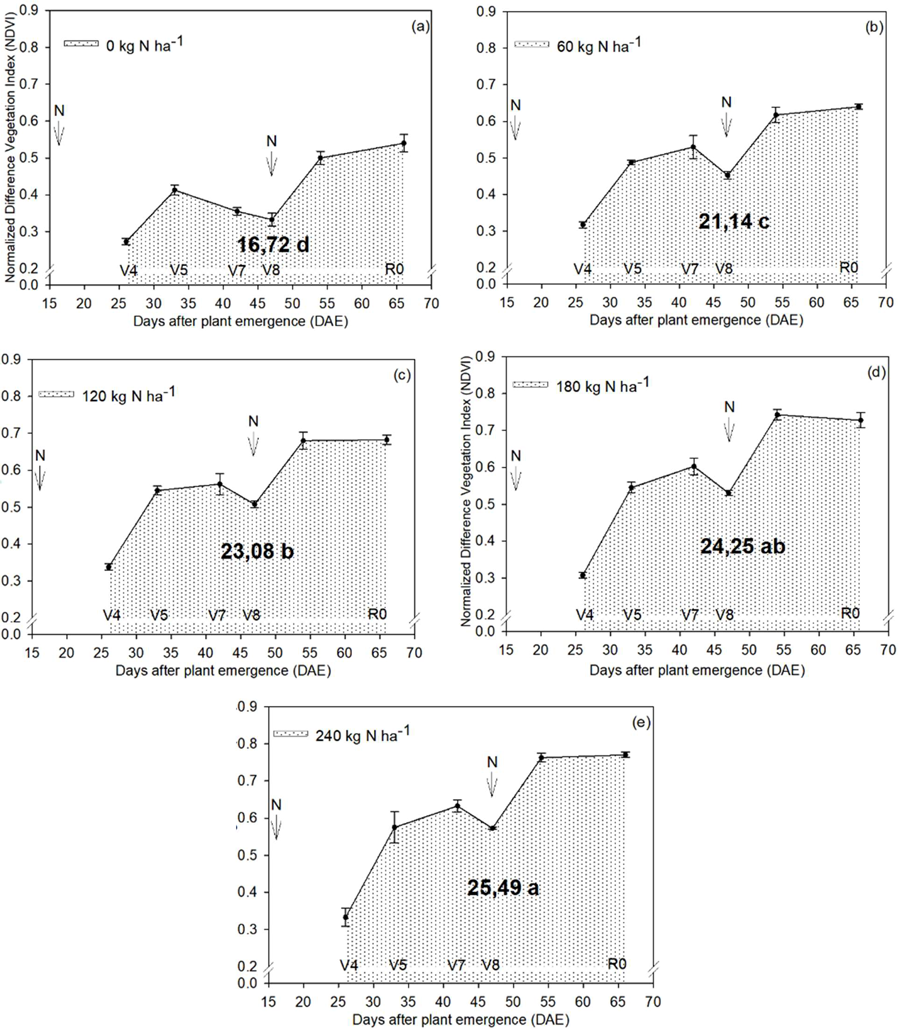

To integrate NDVI responses across growth stages and N rates, the Area Under the NDVI Progress Curve (AUNPC) was calculated from six stages assessed during each season and treatment individually. Higher N rates resulted in higher NDVI values and, consequently, larger AUNPC values due to greater biomass production and canopy reflectance in the NIR band (Figures 4 and 5). These treatments also produced higher yields (Supplementary Figure 1).

Area under the NDVI progress curve (AUNPC) in the 2021/22 season for treatments with no N (a), 60 kg N ha⁻1 (b), 120 kg N ha⁻1 (c), 180 kg N ha⁻1 (d), and 240 kg N ha⁻1 (e). Arrows indicate the timing of nitrogen topdressing; bars represent the standard error of the mean. Lowercase letters compare AUNPC values among treatments at the 5% significance level.

Area under the NDVI progress curve (AUNPC) in the 2022/23 season for treatments with no N (a), 60 kg N ha⁻1 (b), 120 kg N ha⁻1 (c), 180 kg N ha⁻1 (d), and 240 kg N ha⁻1 (e). Arrows indicate the timing of nitrogen topdressing; bars represent the standard error of the mean. Lowercase letters compare AUNPC values among treatments at the 5% significance level.

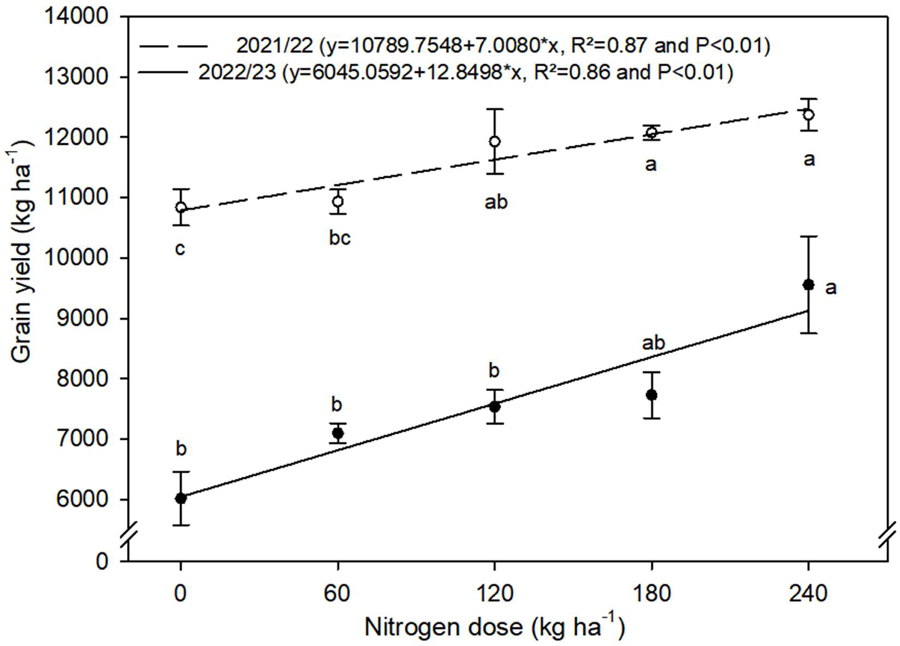

Based on the integrated value of the six NDVI assessments, the relationship between AUNPC and grain yield was evaluated using a single regression across both years (Figure 6).

Relationship between rice grain yield and the area under the NDVI progress curve (AUNPC) as a function of topdressing N rates in the 2021/22 (open symbols) and 2022/23 (solid symbols) growing seasons

A strong positive correlation (R = 0.80; Figure 6) confirmed the accuracy of AUNPC as a predictor of grain yield. Larger AUNPC values corresponded to higher yields, showing that differences in crop N status can be effectively detected by NDVI.

In 2021/22, favorable conditions supported higher yields: adequate rainfall (Figure 2a) maintained adequate water layer in the plots, solar radiation was greater, photosynthesis and N assimilation were maximized (Taiz et al., 2017), and air temperatures remained within the optimal range for rice (Figure 2b) (Yoshida, 1981), thereby increasing grain yield (Supplementary Figure 1). In contrast, the 2022/23 season experienced adverse conditions, with reduced water availability, lower solar radiation, and episodes of stress, which significantly lowered grain yields in all treatments.

Despite differences in grain yield between years, higher N rates consistently promoted greater canopy development, as reflected in AUNPC values (Figures 4 and 5), and resulted in higher yields (Figure 6). Thus, correlating AUNPC with grain yield offers an approach to identify areas with greater or lesser N requirements across the crop cycle rather than at a single stage. Although widely used in plant pathology, this integration method is applied here for the first time in irrigated rice.

These results agree with other studies. Nakano et al. (2023) reported a strong relationship between NDVI measured with the GreenSeeker sensor and rice grain yield when assessed three to one week before panicle initiation (R0 stage). At R0, NDVI correlates positively with rice grain yield (Harrell et al., 2011; Ali et al., 2014; Xue et al., 2014). Islam et al. (2021) predicted grain yield from NDVI at the V9 and R0 stages with a high coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.91). Similarly, Wang et al. (2019) found the highest correlations between NDVI and rice yield at these same growth stages.

Panicle initiation represents the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth and is a critical stage for adjusting N topdressing according to crop nutritional status. Therefore, the N rate recommended for the second topdressing can be guided by NDVI and AUNPC values (Figure 6).

NDVI and crop biophysical parameters

To propose a methodology for adjusting the second nitrogen topdressing rate, aboveground dry biomass and accumulated N were also evaluated and correlated with NDVI values at the eight-leaf stage (V8), which precedes the recommended time for N topdressing at panicle initiation (R0) (Reunião Técnica da Cultura do Arroz Irrigado, 2022). Both shoot biomass and N accumulation reflect the physiological status of plants (Li et al., 2020). Greater biomass accumulation in rice results from the positive effect of N on tiller production, plant height, and leaf area and thickness, which together increase total biomass (Padhan et al., 2023).

In both years, higher N rates increased biomass and shoot N accumulation. These growth differences altered canopy reflectance, with more developed plants showing greater reflectance in the near-infrared (NIR) region and lower reflectance in the red spectrum (Figueiredo, 2005), resulting in higher NDVI values in regions of the field where plants are more developed.

Variations in dry matter between years highlight the influence of meteorological conditions on rice growth and explain the lower NDVI values observed in 2022/23. When NDVI was used to estimate aboveground biomass and accumulated N, high coefficients of determination (R2) were obtained (Figure 7), consistent with the findings of Chen et al. (2023) and Qun et al. (2023).

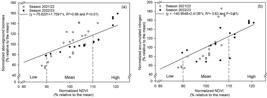

Relationship between aboveground dry biomass (a) and accumulated N (b) of irrigated rice and the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) at the eight-leaf stage (V8) in the 2021/22 and 2022/23 seasons. The dashed line indicates the 2021/22 season and the solid line indicates the 2022/23 season.

The strong relationship between direct plant variables (biomass and shoot N) and NDVI supports the use of the index to estimate crop N status during the growing season, prior to N supplementation. Lu et al. (2022) and Yinyan et al. (2023) also reported that variable N fertilization guided by NDVI increased rice final grain yield and reduced fertilizer use compared with traditional uniform rate fertilization.

Adjusting nitrogen rates during the growing season

Although aboveground dry biomass and accumulated N show a linear relationship with NDVI, their absolute values varied between seasons (Figure 7). Thus, N topdressing prescription models based solely on absolute NDVI values may under- or overestimate variability in crop development caused by N availability (Solie et al., 2012; Aranguren et al., 2019).

To reduce these variations and enable broader application of NDVI, a normalization approach was tested using the mean value of each experiment (season). This procedure allowed the development of a single regression to characterize spatial variability in irrigated rice and to guide N topdressing at the V8 stage (Figure 8). By normalizing the data, the two seasons could be analyzed jointly (Amaral et al., 2015), supporting the proposal of a single model applicable across years and cropping conditions.

Relationship between normalized values of aboveground biomass (a) and accumulated nitrogen in the biomass (b) of irrigated rice and the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) at the eight-leaf stage (V8).

Normalized data were grouped into three classes, following the model of Vian et al. (2018) for wheat. Based on these classes, the model in Figure 8 may identify critical development regions in the field from biomass (Figure 8a) and shoot N accumulation (Figure 8b), providing a framework for defining management zones to redistribute N topdressing according to the crop’s average NDVI. The classes were defined as follows: low (<90% of the field average NDVI, where 100% is the mean), medium (90–110%), and high (>110%). This framework enables N prescription across different crops and years.

As shown in Figure 8, the “low” class (NDVI <90% of the average) corresponded to dry biomass production (Figure 8a) and shoot N accumulation (Figure 8b) below approximately 80% and 70% of the mean, respectively, indicating reduced vegetative growth and N deficiency. In contrast, the “high” class (NDVI >110% of the average) corresponded to dry biomass production and shoot N accumulation near 115% and 120% of the mean, respectively. These critical zones provide a practical method to refine N topdressing. For instance, in the “low” class at the V8 stage, biomass and shoot N accumulation shows a deficit of approximately 20% and 30%, respectively, relative to the mean. In this scenario, we suggest that N doses should be increased by around 30% in these zones in the field compared with the uniform application rate.

This procedure helps prevent N deficits in less developed areas of the field at the V8 stage (“low” zone) and avoids excess N in areas with high biomass and shoot N accumulation (“high” zone). In the intermediate class (“medium” zone), the N dose follows the standard technical recommendations, which consider soil organic matter content and the expected crop response to fertilization (Reunião Técnica da Cultura do Arroz Irrigado, 2022) and can be adjusted according to the yield potential estimated from Figure 6. Thus, this study proposes a model for redistributing topdressing N doses in irrigated rice at the V8 stage by applying variable rates, starting from the average dose defined by the farmer or technical consultant.

Applying N doses consistent with plant nutritional demand at the time of application maximizes N absorption, increases grain yield potential in nutrient-limited areas, and reduces both fertilizer costs and N losses (leaching, volatilization, and denitrification) in areas where application would otherwise exceed plant requirements (Diacono et al., 2013; Castelli et al., 2019).

CONCLUSIONS

Rice productivity can be predicted throughout the crop cycle by monitoring NDVI and calculating the area under the NDVI progress curve (AUNPC). NDVI showed strong correlations with crop biophysical parameters, such as aboveground biomass and shoot N accumulation at the V8 stage, confirming its effectiveness for estimating these variables and assessing plant nutritional status. Nevertheless, the strong year effect observed highlights the limitations of applying these relationships universally. By applying data normalization, this study proposes a general model for classifying variability in plant growth and shoot N accumulation in irrigated rice, enabling adjustment of the second N topdressing rate and optimizing crop response to nitrogen.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE:

Grain yield of irrigated rice as a function of nitrogen topdressing doses in the 2021/22 and 2022/23 growing seasons. Bars represent the standard error of the mean. Dashed lines indicate the 2021/22 season, and solid lines indicate the 2022/23 season. Lowercase letters denote mean comparisons at the 5% significance level among treatments within each season.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been supported by the EMBRAPII Center for Embedded Devices and Research in Digital Agriculture (CEDRA) of SENAI-RS, with financial resources from the PPI IoT/Manufatura 4.0 / PPI HardwareBR of the MCTI, grant number 056/2023, signed with EMBRAPII.

REFERENCES

-

Ali, A. M., Tind, H. S., Sharma, S., & Singh, V. (2014). Prediction of dry direct-seeded rice yields using chlorophyll meter, leaf color chart and GreenSeeker optical sensor in northwestern India. Field Crops Research, 161, 11 - 15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2014.03.001

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2014.03.001 - Amaral, T. A., Andrade, C., Duarte, J. O., Garcia, J. C., Garcia, A. G., Silva, D. F., Albernaz, W. M., & Hoogenboom, G. (2015). Nitrogen management strategies for smallholder maize production systems: Yield and profitability variability. International Journal of Plant Production, 9 (1), 75-98.

- Amorim, L. (1995). Avaliação de doenças. In F. A. Bergamin, H. Kimati, & L. Amorim (Eds.), Manual de fitopatologia ( pp. 647-671). Agronômica Ceres.

-

An, N., Wei, W., Qiao, L., Zhang, F., Christie, P., Jiang, R., Dobermann, A., Goulding, K. W. T., Fan, J., & Fan, M. (2018). Agronomic and environmental causes of yield and nitrogen use efficiency gaps in Chinese rice farming systems. European Journal of Agronomy, 93, 40 - 49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2017.11.001

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2017.11.001 -

Aranguren, M., Castellón, A., & Aizpurua, A. (2019). Crop sensor-based in-season nitrogen management of wheat with manure application. Remote Sensing, 11 (9), 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11091094

» https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11091094 -

Ata-Ul-Karim, S. T., Zhu, Y., Liu, X., Cao, Q., Tian, Y., & Cao, W. (2017). Comparison of different critical nitrogen dilution curves for nitrogen diagnosis in rice. Scientific Reports, 7, 42679. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42679

» https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42679 -

Baral, B. R., Pande, K. R., Gaihre, Y. C., & Baral, K. R. (2021). Real-time nitrogen management using decision support tools increases nitrogen use efficiency of rice. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 119, 355-368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-021-10129-6

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-021-10129-6 -

Bolstad, W. M. (2009). Understanding computational Bayesian statistics. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470567371

» https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470567371 -

Cao, Q., Miao, Y., Li, F., Gao, X., Liu, B., Lu, D., & Chen, X. (2017). Developing a new crop circle active canopy sensor-based precision nitrogen management strategy for winter wheat in North China Plain. Precision Agriculture, 18, 2-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-016-9456-7

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-016-9456-7 - Castelli, G., Rosolem, C. A., Cantarella, H., & Anghinoni, I. (2019). Eficiência do uso do nitrogênio em agroecossistemas. Tópicos em Ciência do Solo, 10 (1), 141-238.

-

Chen, K., Ma, T., Ding, J., Yu, S., Dai, Y., He, P., & Ma, T. (2023). Effects of straw return with nitrogen fertilizer reduction on rice ( Oryza sativa L.) morphology, photosynthetic capacity, yield and water-nitrogen use efficiency traits under different water regimes. Agronomy, 13 (1), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13010133

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13010133 -

Diacono, M., Rubino, P., & Montemurro, F. (2013). Precision nitrogen management of wheat: A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 33, 219-241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-012-0111-z

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-012-0111-z -

Duan, B., Fang, S., Gong, Y., Peng, Y., Wu, X., & Zhu, R. (2021). Remote estimation of grain yield based on UAV data in different rice cultivars under contrasting climatic zone. Field Crops Research, 267, 108148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2021.108148

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2021.108148 -

Figueiredo, D. (2005). Conceitos de sensoriamento remoto https://www.clickgeo.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/conceitos_sm.pdf

» https://www.clickgeo.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/conceitos_sm.pdf -

Harrell, D. L., Tubaña, B. S., Caminhante, T. W., & Phillips, S. B. (2011). Estimating rice grain yield potential using normalized difference vegetation index. Agronomy Journal, 103, 1717-1723. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2011.0202

» https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2011.0202 -

Islam, M. M., Matsushita, S., Noguchi, R., & Ahamed, T. (2021). Development of remote sensing-based yield prediction models at the maturity stage of boro rice using parametric and nonparametric approaches. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, 22, 100494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsase.2021.100494

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsase.2021.100494 -

Kanke, Y., Tubaña, B., Dalen, M., & Harrell, D. (2016). Evaluation of red and red-edge reflectance-based vegetation indices for rice biomass and grain yield prediction models in paddy fields. Precision Agriculture, 17, 507-530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-016-9433-1

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-016-9433-1 -

Knoblauch, R., Ernani, P. R., Walker, T. W., & Krutz, L. J. (2012). Ammonia volatilization in waterlogged soils influenced by the form of urea application. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, 36(3), 813-822. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832012000300012

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832012000300012 -

Li, B., Xu, X., Zhang, L., Han, J., Bian, C., Li, G., Liu, J., & Jin, L. (2020). Above-ground biomass estimation and yield prediction in potato by using UAV-based RGB and hyperspectral imaging. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 162, 161-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2020.02.013

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2020.02.013 -

Lu, J., Dai, E., Miao, Y., & Kusnierek, K. (2022). Improving active canopy sensor-based in-season rice nitrogen status diagnosis and recommendation using multi-source data fusion with machine learning. Journal of Cleaner Production, 380, 134926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134926

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134926 - Molin, J. P. (2002). Definição de unidades de manejo a partir de mapas de produtividade. Engenharia Agrícola, 22 (1), 83-92.

-

Nakano, H., Tanaka, R., Guan, S., & Ohdan, H. (2023). Predicting rice grain yield using normalized difference vegetation index from UAV and GreenSeeker. Crop and Environment, 2 (2), 59-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crope.2023.03.001

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crope.2023.03.001 -

Padhan, B. K., Sathee, L., Kumar, S., Chinnusamy, V., & Kumar, A. (2023). Variation in nitrogen partitioning and reproductive stage nitrogen remobilization determines nitrogen grain production efficiency (NUEg) in diverse rice genotypes under varying nitrogen supply. Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 1093581. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1093581

» https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1093581 -

Padilla, F. M., Gallardo, M., Peña-Fleitas, M. T., De Souza, R., & Thompson, R. B. (2018). Proximal optical sensors for nitrogen management of vegetable crops: A review. Sensors, 18 (7), 2083. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18072083

» https://doi.org/10.3390/s18072083 - Poletto, N. (2004). Disponibilidade de nitrogênio no solo e sua relação com o manejo da adubação nitrogenada [Master dissertation, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul].

-

Queiroz, D. M., Coelho, A. L. F., Valente, D. S. M., & Schueller, J. K. (2020). Sensors applied to digital agriculture: A review. Revista Ciência Agronômica, 51, e20200086. https://doi.org/10.5935/1806-6690.20200086

» https://doi.org/10.5935/1806-6690.20200086 -

Qun, Z., Rui, Y., Wei-yang, Z., Jun-fei, G., Li-jun, L., Hao, Z., Zhi-qin, W., & Jian-chang, Y. (2023). Grain yield, nitrogen use efficiency and physiological performance of indica/japonica hybrid rice in response to various nitrogen rates. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 22 (1), 63-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2022.08.076

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2022.08.076 -

Rehman, T. H., Reis, A. F. B., Akbar, N., & Linquist, B. A. (2019). Use of normalized difference vegetation index to assess N status and predict grain yield in rice. Agronomy Journal, 111, 2889-2898. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2019.03.0217

» https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2019.03.0217 -

Reunião Técnica da Cultura do Arroz Irrigado. (2022). Recomendações técnicas da pesquisa para o sul do Brasil. Instituto Rio Grandense do Arroz. https://www.sosbai.com.br/uploads/documentos/recomendacoes-tecnicas-da-pesquisa-para-o-sul-do-brasil_310.pdf

» https://www.sosbai.com.br/uploads/documentos/recomendacoes-tecnicas-da-pesquisa-para-o-sul-do-brasil_310.pdf - Rouse, J. W., Haas, R. H., Schell, J. A., & Deering, D. W. (1974). Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS NASA.

- Santos, H. G., Jacomine, P. K. T., Anjos, L. H. C., Oliveira, V. A., Lumbreras, J. F., Coelho, M. R., Almeida, J. A., Araújo, F. J. C., Oliveira, J. B., & Cunha, T. J. F. (2013). Sistema brasileiro de classificação de solos Embrapa Solos.

-

Serrano, L., Filella, I., & Peñuelas, J. (2000). Remote sensing of biomass and yield of winter wheat under different nitrogen supplies. Crop Science, 40, 723-731. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2000.403723x

» https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2000.403723x -

Singh, B., Singh, V., Purba, J., Sharma, R. K., Jat, M. L., Singh, Y., Fino, H. S., Gupta, R. K., Chaudhary, O. P., Chandna, P., Khurana, H. S., Kumar, A., Singh, J., Uppal, H. S., Uppal, R. K., Vashistha, M., & Gupta, R. (2015). Site-specific fertilizer nitrogen management in irrigated transplanted rice ( Oryza sativa ) using an optical sensor. Precision Agriculture, 16, 455 - 475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-015-9389-6

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-015-9389-6 -

Solie, J. B., Monroe, A. D., Raun, W. R., & Stone, M. L. (2012). Generalized algorithm for variable-rate nitrogen application in cereal grains. Agronomy Journal, 104 (2), 378 - 387. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2011.0249

» https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2011.0249 - Taiz, L., Zeiger, E., Møller, I. M., & Murphy, A. (2017). Fisiologia e desenvolvimento vegetal Artmed Editora.

- Tedesco, M. J., Gianello, C., Bissani, C. A., Bohnen, H., & Volkweiss, S. J. (1995). Análise de solo, plantas e outros materiais. Departamento de Solos da UFRGS.

-

Vian, A. L., Bredemeier, C., Silva, P. R. F. D., Santi, A. L., Silva, C. P. G. D., & Santos, F. L. D. (2018). Limites críticos de NDVI para estimativa do potencial produtivo do milho. Revista Brasileira de Milho e Sorgo, 17 (1), 91-100. https://doi.org/10.18512/1980-6477/rbms.v17n1p91-100

» https://doi.org/10.18512/1980-6477/rbms.v17n1p91-100 -

Xue, L., Li, G., Qin, X., Yang, L., & Zhang, H. (2014). Topdressing nitrogen recommendation for early rice with an active sensor in South China. Precision Agriculture, 15, 95 - 110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-013-9326-5

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-013-9326-5 -

Wang, F., Wang, F., Zhang, Y., Hu, J., Huang, J., & Xie, J. (2019). Rice yield estimation using parcel-level relative spectral variables from UAV-based hyperspectral imagery. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10, 53. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00453

» https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00453 -

Yinyan, S., Man, C., Wang, X., Haolin, Y., Haiming, Y., & Xiangze, H. (2023). Efficiency analysis and evaluation of centrifugal variable-rate fertilizer spreading based on real-time spectral information on rice. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 204, 107505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2022.107505

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2022.107505 - Yoshida, S. (1981). Fundamentals of rice crop science. International Rice Research Institute.

-

Zhang, K., Liu, X., Mestre, J., Wang, Y., Cao, Q., Zhu, Y., Cao, W., & Tian, Y. (2021). A new canopy chlorophyll index-based paddy rice critical nitrogen dilution curve in eastern China. Field Crops Research, 266, 108139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2021.108139

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2021.108139

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT:

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Edited by

-

Area Editor:

Anildo Monteiro Caldas

-

Edited by

SBEA

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

21 Nov 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

29 Aug 2024 -

Accepted

23 Sept 2025

NDVI-Based METHOD FOR OPTIMIZING Nitrogen Fertilization in Irrigated Rice

NDVI-Based METHOD FOR OPTIMIZING Nitrogen Fertilization in Irrigated Rice