ABSTRACT

At present, in the field of cherry recognition, problems such as dense fruit growth and frequent occlusions of branches and leaves affect the accuracy of the recognition process. To address these issues, this paper proposes a lightweight cherry detection model based on an improved YOLOv8n (CHERRY-YOLO). By introducing a FasterNet block module based on partial convolution (PConv) and replacing the bottleneck module in YOLOv8n's C2f with a FasterNet block module, a new C2f-Faster module is formed. As the module reduces the number of parameters and calculations, it also ensures high detection accuracy. By adding a convolutional block attention module (CBAM) between the SPPF module and C2f-Faster module in the backbone network area, the ability to extract target features is enhanced before multiscale feature map fusion, further improving the target detection accuracy. The experimental results show that CHERRY-YOLO has more advantages than the original YOLOv8n model. Its precision, mAP@0.5, mAP@0.5:0.95, and recall increase by 1.3%, 1.0%, 0.6%, and 0.4%, respectively. Moreover, the number of parameters, computational size, and weight decrease by 21.27%, 20.99%, and 20.63%, respectively. The results demonstrate that CHERRY-YOLO provides important technical support for automatic cherry picking.

KEYWORDS

cherry detection; YOLOv8n; lightweighting; partial convolution; attention mechanism

INTRODUCTION

Currently, cherry picking is usually performed manually; owing to the short cherry ripening period, the available rural working population is low, and the picking labor intensity is high (Zhang et al., 2022). An automated picking robot can improve picking efficiency, reduce damage to fruit, and reduce labor costs (Ji et al., 2012). As a component of the fruit and vegetable picking robot system, the visual recognition system plays a vital role in fruit and vegetable target identification and localization, automatic picking, and fruit and vegetable yield estimation (Song et al., 2023). Owing to the high densities, overlapping positions of cherries as they grow, small fruits, and severe shade from branches and leaves, harvesting is the most time-consuming and labor-intensive task. Therefore, it is important to study the visual automatic detection systems with high recognition rates, and use these systems to determine the ripening condition, location, and quantity of cherry fruits in natural environments to implement automatic cherry picking.

At present, research on fruit recognition has made important achievements. In the early years, the traditional detection method recognized fruit by their color and shape features (Islam et al., 2022; Liakhov et al., 2022); however, this method was strongly affected by changes in light intensity and environmental background, and it was difficult to improve the detection accuracy.

In recent years, target detection methods based on deep learning have been widely used in the field of fruit recognition. Li et al. (Li et al., 2024a) proposed a lightweight improved YOLOv5s model. By reconstructing the backbone with Shufflenetv2 and integrating multiple modules and strategies, it was able to detect pitaya fruits in different lighting environments. It achieved an AP of 97.80%, 139 FPS on a GPU, with a 2.5-MB size, and enabled real-time detection on a real-time GT Android phone. Meng et al. (Meng et al., 2023) presented a spatiotemporal convolutional neural network model for pineapple fruit detection. By comparing traditional models, and studying data preparation factors, the detection accuracy reached 92.54%, with an average reasoning time of 0.163 s. Chen et al. (Chen et al., 2024) proposed a visual algorithm for motion destination estimation, self-localization, and dynamic picking. A coordination mechanism was established, and field experiments verified its effectiveness in addressing the visual servo control problem in complex orchards for fruit-picking robots. Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2024) proposed an unstructured orchard grape detection method based on YOLOv5s. By introducing a dual-channel feature enhancement structure and dynamic serpentine convolution, the model's accuracy was improved by 1.4% compared with that of YOLOv5s. Yang et al. (Yang et al., 2023) proposed an improved YOLOv7-based apple target recognition method. By conducting image preprocessing, introducing the MobileOne module, and optimizing the SPPCSPS module, they enhanced the algorithm's accuracy by 6.9%. Xiao et al. (Xiao et al., 2024) used the YOLOv8 model to recognize fruit ripeness, upsampled the feature map using the deconvolution module DeConv, and used the CSP and C2f modules for lightweight processing, which significantly improved the classification results, with a resulting accuracy of up to 99.5%. Sekharamantry et al. (Sekharamantry et al., 2023) used an improved model for apple recognition detection by improving the loss function and adding an attention mechanism based on the YOLOv5 model, with a resulting detection accuracy of 97%. Mirhaji et al. (Mirhaji et al., 2021) used the YOLOv4 model to train and verify an orange dataset through migration learning, and the experimental results revealed that the accuracy rate reached 91.23%. Sun et al. (Sun et al., 2023) proposed an improved YOLOv5-based method for fast pear detection in complex orchard picking environments. By optimizing the backbone network and incorporating the CBAM attention mechanism, it enhanced the target feature extraction process. The improved model achieved average accuracies 97.6%, 1.8% higher than those of the original model. Zhong et al. (Zhong et al., 2024) proposed Light-YOLO, a lightweight and efficient mango detection model based on the Darknet53 structure, which, according to the experimental results, achieved an average accuracy mean of 96.1% on the mango dataset.

Previous studies indicated that the deep learning methods excel in fruit detection, and scholars have explored cherry fruit recognition using these technologies. Li et al. (Li et al., 2022) proposed a YOLOX-based real-time algorithm for detecting sweet cherry maturity in natural settings. By inserting CBAM and using EIoU loss, it achieved 81.1% accuracy (4.12% higher than the original YOLOX) but had a large 34.87 MB size and a slow detection speed of 0.64 s per image. Gai et al. (Gai et al., 2023) proposed a cherry fruit detection algorithm based on the improved YOLO-v4 model, which enhanced the extraction of image features by changing the backbone network, and the mean average accuracy of the improved model increased by only 0.15%. Although the above research improves detection models through deep learning technology, the improved models are not sufficiently lightweight, and their detection speed and accuracy need to be further improved.

To resolve the these issues, this paper presents a lightweight cherry detection model based on an improved YOLOv8n. By substituting the bottleneck module in C2f with the FasterNet Block module using a partial convolution, it achieves a lightweight design without sacrificing detection accuracy. Additionally, integrating the CBAM in the backbone network enhances target feature extraction and further increases detection accuracy. This enhanced lightweight model offers better technical support in visual recognition for cherry-picking robots.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Data acquisition

On April 27, 2024, the research team conducted an image acquisition experiment in a cherry picking garden in Luolong District, Luoyang City, Henan Province. To ensure the richness of the dataset in terms of the environmental variables, in the experiment, mornings, noons and afternoons with significant light differences were selected, and a HONOR 80GT mobile phone was used to shoot mature and immature cherry fruits under different shading levels. In the process of shooting, the light receiving angle and shooting distance of the fruit were comprehensively considered, and image data covering different lighting conditions, such as smooth light and backlight, as well as a variety of shooting angles, such as long distances and short distances, were obtained.

Finally, after strict screening and sorting, 532 high-quality images with a resolution of 4096 × 3072 pixels were obtained. Based on the content and characteristics, these images could be systematically divided into eight types: ripe fruits, unripe fruits, shaded by branches and leaves, overlapping fruits, smooth light, back light, long-distance shooting and close-distance shooting. Typical examples of each type of image are shown in Figure 1.

Dataset construction

The collected images were labeled with rectangular boxes using LabelImg software and divided into ripe and unripe categories, and the labeling method was as follows:

-

The completely exposed cherry fruits were labeled;

-

Exposed fruits of cherries subjected to obscured conditions were labeled;

-

Fruits that were severely obscured so that they could not be artificially distinguished from the category were not labeled.

After the labeling was completed, an XML file containing the center coordinates of the cherry, as well as the width and height information, was obtained. As the YOLO series detection model needs a txt-type annotation file, Python was used to write a corresponding program to convert the xml-type annotation file to a txt-type annotation file. All the images and corresponding annotation files were randomly divided into a training set and a validation set at an 8:2 ratio. There were a total of 7914 annotation instances in the training set and 2192 annotation instances in the validation set.

Online augmented data availability is crucial during model training and validation. Various methods were employed to increase recognition accuracy, these include mosaic stitching of multiple images and increasing the scene complexity so the model can learn target features from different combinations. Hybrid operations fuse the images to enrich data diversity, helping the model adapt to real-world scenes. Random perspectives simulate object perspective changes, optimizing the model's scale adaptability for accurate identification at different angles. HSV enhancements randomly adjust an image's hue, saturation, and value, altering color characteristics to improve the model's recognition under diverse lighting and color conditions. These techniques significantly increased the dataset diversity, as shown in Figure 2.

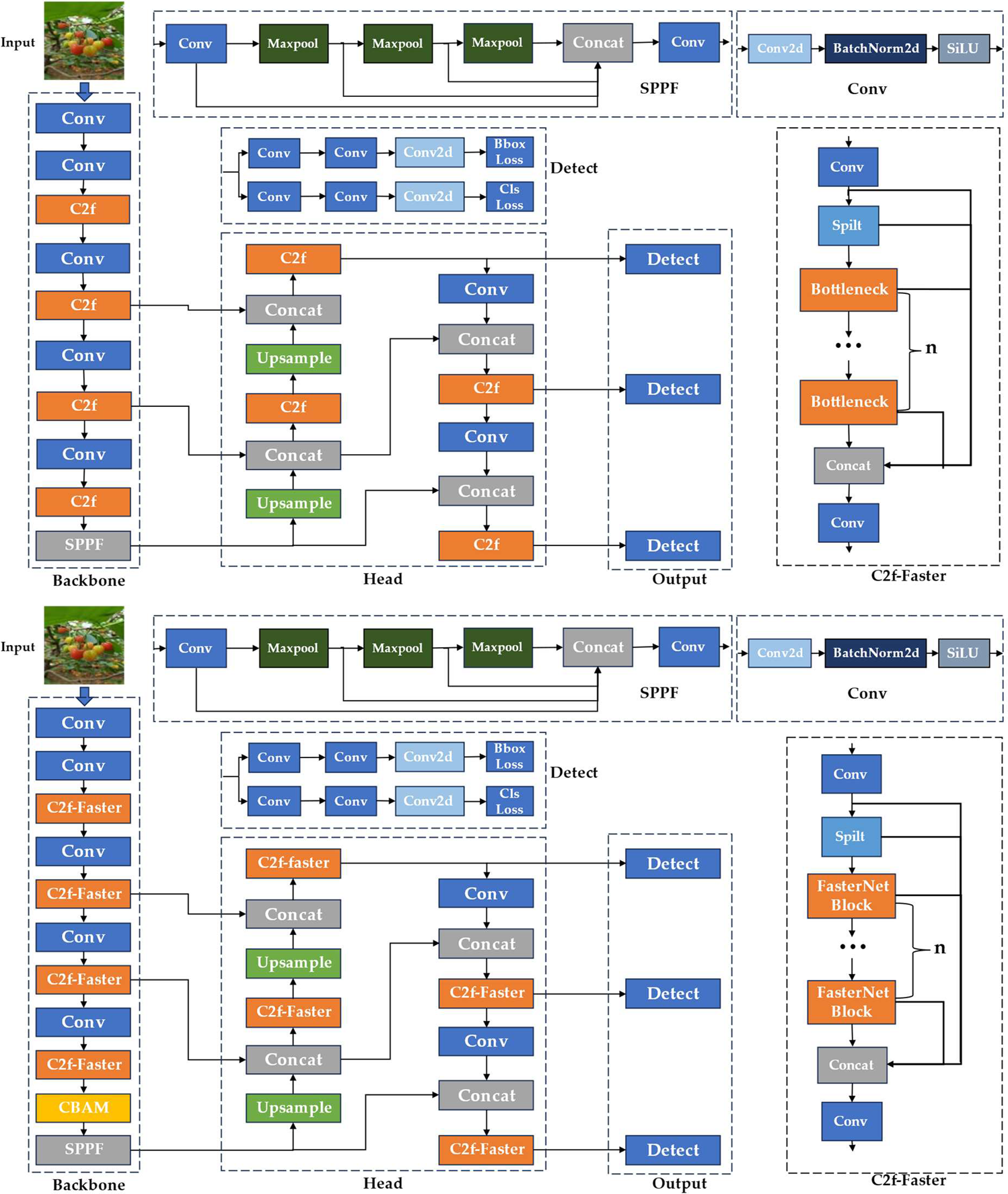

The CHERRY-YOLO network model

YOLOv8 is an advanced object detection algorithm developed by Ultratics. Currently, the YOLOv8 family includes five distinct size configurations: YOLOv8n, YOLOv8s, YOLOv8m, YOLOv8l, and YOLOv8x. The architecture of YOLOv8 primarily comprises the input, backbone network, head network, and output (Gao et al., 2024). It uses a more efficient backbone network coupled with an innovative detection head design, enabling the model to maintain high speed while enhancing the accuracy of object recognition and localization. Leveraging its sophisticated network architecture and algorithmic design, YOLOv8 significantly enhances both the accuracy and speed of object detection. YOLOv8 exhibits outstanding performance in both static images and video streams. Considering the limited computing resources of edge devices, YOLOv8n was chosen as the baseline model and was subsequently improved. The YOLOv8 network model’s structure is shown in Figure 3a.

The network structures: (a) the YOLOv8 network structure and (b) the CHERRY-YOLO network structure.

First, the FasterNet block module based on a partial convolution is introduced, and the bottleneck module in C2f of YOLOv8n is replaced to form a new C2f-Faster module, which can significantly reduce the number of parameters and computations while ensuring high detection accuracies. Second, by adding the CBAM attention mechanism module between the SPPF module and the C2f-Faster module in the backbone network area, the detection accuracy of the target is further enhanced before the fusion of the multiscale feature maps, and the feature extraction capability of the target is enhanced. The CHERRY-YOLO network model structure is shown in Figure 3b.

FasterNet Block model

The C2f module in the original YOLOv8n model uses the bottleneck module, whose structure is shown in Figure 4. This module is composed of two 3×3 conventional convolutions in series, and it performs batch normalization and SiLU activation function operations after each convolution. Finally, the result obtained from the convolution is summed with the feature map at the input. Since the bottleneck module performs a regular convolution operation on each channel of the input feature map, excessive redundancy of channel information occurs while more features are extracted, which results in greater computational overhead (Li et al., 2024b).

In the FasterNet Block module, by introducing the Pconv operation to reduce redundant calculations and memory access, the spatial features can be extracted more effectively. Its structure is shown in Figure 5. The first layer is a partial convolution layer with a convolution kernel size of 3 × 3, which is followed by two dot convolution layers with a convolution kernel size of 1 × 1. A normalization layer and an activation layer are placed behind the intermediate convolution layer to maintain the diversity of

features and reduce complexity and delay. Finally, the final output feature map is obtained by summing the partially convoluted features with the input features. Because the characteristic maps of the different channels are highly similar, the partial convolution of the input characteristic map does not affect the accuracy (Chen et al., 2023).

PConv is a partial convolution, and its structure is shown in Figure 6. Unlike the conventional convolution for all channels of the input feature map, PConv only convolves a part of the channels of the input feature map, and the remaining channels are not processed. Assuming that the length, width, and channel values of the input feature map are a, b, and c, respectively, cp is the number of channels involved in convolution, k is the size of the convolution kernel, the computational amount of partial convolution Fp is expressed in [eq. (1)], and the memory access amount Mp is shown in [eq. (2)]. Pr is the proportion of the channels involved in the convolution, as shown in [eq. (3)]. When the participating convolution channel ratio is taken as 1/4, the computation amount of the partial convolution is only 1/16 of the normal convolution, and the memory access is only 1/4 of the normal convolution. Therefore, the use of partial convolutions can reduce redundant computations and memory access.

CBAM Attentional Mechanisms

In deep learning, the attention mechanism is a machine vision mechanism that can process visual information very efficiently by mimicking the way the human brain thinks when processing visual inputs; it quickly focuses attention on important regions in the image and ignores irrelevant background regions (Niu et al., 2021). The CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module) is a lightweight attention module (Woo et al., 2018) that combines channel attention and spatial attention, and its advantage is that it is able to focus on both channel and spatial dimensions simultaneously; it suppresses noise and irrelevant information while retaining critical information. For example, when a fruit is partially occluded by leaves, channel attention can focus on the channels where the color and texture features of the fruit are located. Moreover, the spatial attention mechanism highlights the unoccluded parts and boundaries of the occluded objects, which helps the model better locate the positions of the occluded objects. With respect to small target detection, CBAM can enhance the feature representation of small targets by automatically mining their unique features in both the channel and spatial dimensions.

The hybrid attention mechanism is designed to perform the integration of the channel dimension first, and then the spatial dimension; this leads to more effective feature enhancement. The model performance is greatly enhanced with a slight increase in the computational and parametric quantities. CBAM captures the correlation between features by adaptively learning the channel and spatial attention weights to enhance the performance of the image recognition tasks.

The attention mechanism of CBAM can be subdivided into two parts: the channel attention mechanism (Shan et al., 2022) and the spatial attention mechanism (Guo et al., 2022); its structure is shown in Figure 7a. Figure 7b is represented as a channel attention mechanism module, where each channel of the input feature map F is first subjected to global maximum pooling and global average pooling operations to obtain two 1-channel feature maps, and then the global maximum pooled and average pooled channel feature maps are input into a shared network layer. This shared network layer is used to learn the attention weights of each channel, through which the network can adaptively decide which channels are most important for the current task. After that, the output feature maps from the shared network layer are summed and activated by a sigmoid function to generate the final channel feature map Mc, and finally, Mc and the input feature map F are multiplied to generate the input features F1 needed by the spatial feature map module. Figure 7c represents a spatial attention mechanism module, and the feature map F1 output from the channel attention mechanism module is used as an input feature map for this module. The input feature map F1 is first subjected to channel-based global maximum pooling and global average pooling operations sequentially to obtain two 1-channel feature maps, and then these two feature maps are subjected to channel splicing operations and a convolution kernel size of 7×7 convolution operations to downscale to a 1-channel feature map. Then, the spatial feature map Ms is generated by a sigmoid activation function, and finally, this Ms is multiplied by the input feature map F1 of the spatial attention mechanism module to obtain the final generated feature map.

CBAM module structure: (a) CBAM, (b) channel attention module, (c) spatial attention module.

Test environment and parameter configuration

The experiments are conducted using a desktop computer for training and validation, which is configured as a 13th Gen Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-13400F 2.50 GHz central processor with a memory size of 16 GB and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050 graphics card with a graphics memory size of 8 GB in a Windows 11 system environment. The model uses the PyTorch 2.0 deep learning framework, and Python3.8 and CUDA 11.0 for network model construction, training, and validation. The model training optimizer uses the AdamW cosine annealing algorithm with an initial learning rate of 0.001667, momentum of 0.9, and weight decay of 0.0005. The training input image has a pixel resolution of 640×640, an IOU value of 0.5, a batch size of 4, and 300 iterations.

Evaluation indicators

In this study, precision (P), recall (R), mean average precision (mAP), model weight and size, parameter size, and computational size were used as evaluation metrics (Bai et al., 2024; Lin et al., 2024; Shuai et al., 2023). The formulas for P, R, and mAP are as follows:

In [eq. (4)] and [eq. (5)], Tp is the number of correctly predicted positive samples; Fp is the number of incorrectly predicted positive samples; Fn is the number of incorrectly predicted negative samples; AP in [eq. (6)] is the average precision, which is an integral over the product of precision and recall, and represents an indicator of the average precision of the model for a particular category; and mAP in [eq. (7)] represents the average of the average precision across all categories; N represents the number of detected target categories.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Ablation results

In this study, to verify the effectiveness of the various improvement measures, and analyze their impact on the performance indicators of CHERRY-YOLO, an ablation experiment is conducted. The results of the ablation test are shown in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, after replacing the bottleneck module in the C2f module of YOLOv8n with the FasterNet Block module based on a partial convolution, the trained model decreases in terms of weight, parameter size, and computation size; while the precision decreases by 1.6 percentage points, the recall improves by 0.5 percentage points, and the mAP@0.5 and the mAP@0.5:0.95 are slightly reduced, both by 0.2 percentage points. To ensure that the mean average precision is not excessively lost, the model’s weight size, size of parameters, and computational size are reduced by 23.80, 23.46, and 22.22 percentage points. After adding the CBAM attention mechanism between the C2f module and the SPPF module in the backbone network region of the YOLOv8n model, the trained model has a slightly greater weight size, the parameter size increases slightly, and the computational size remains the same; however, the precision decreases by 1.0 percentage points, the recall increases by 0.6 percentage points, the mAP@0.5 increases by 0.1 percentage points, and the mAP@0.5:0.95 decreases by 0.2 percentage points. After adding the FasterNet Block module and the CBAM attention mechanism at the same time, compared with the YOLOv8n model, the trained model decreases in weight size, parameter size, and computational size by 20.63, 21.23, and 20.99 percentage points, respectively, while the precision, recall, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95 increase by 1.3, 0.4, 1.0, and 0.6 percentage points. The lightweight design is accomplished while further improving the model performance. In the process of improving the lightweight model of cherry detection via YOLOv8n, a single introduction of the CBAM attention mechanism, or replacement of the bottleneck module in the C2f module with the partially convolution-based FasterNet block module, does not achieve good results, and only the simultaneous implementation of the two improvement methods can achieve the expected results.

The results of the original YOLOv8n model and CHERRY-YOLO model in terms of precision, recall, map@0.5, and map@0.5:0.95 are shown in Figure 8. After the 200th round of iterations, CHERRY-YOLO has higher precision, recall, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95 values than the original YOLOv8n model does.

Comparison of the CHERRY-YOLO and YOLOv8n model metrics: (a) mAP@0.5, (b) mAP@0.5:0.95, (c) precision, (d) recall.

Comparative test of different models

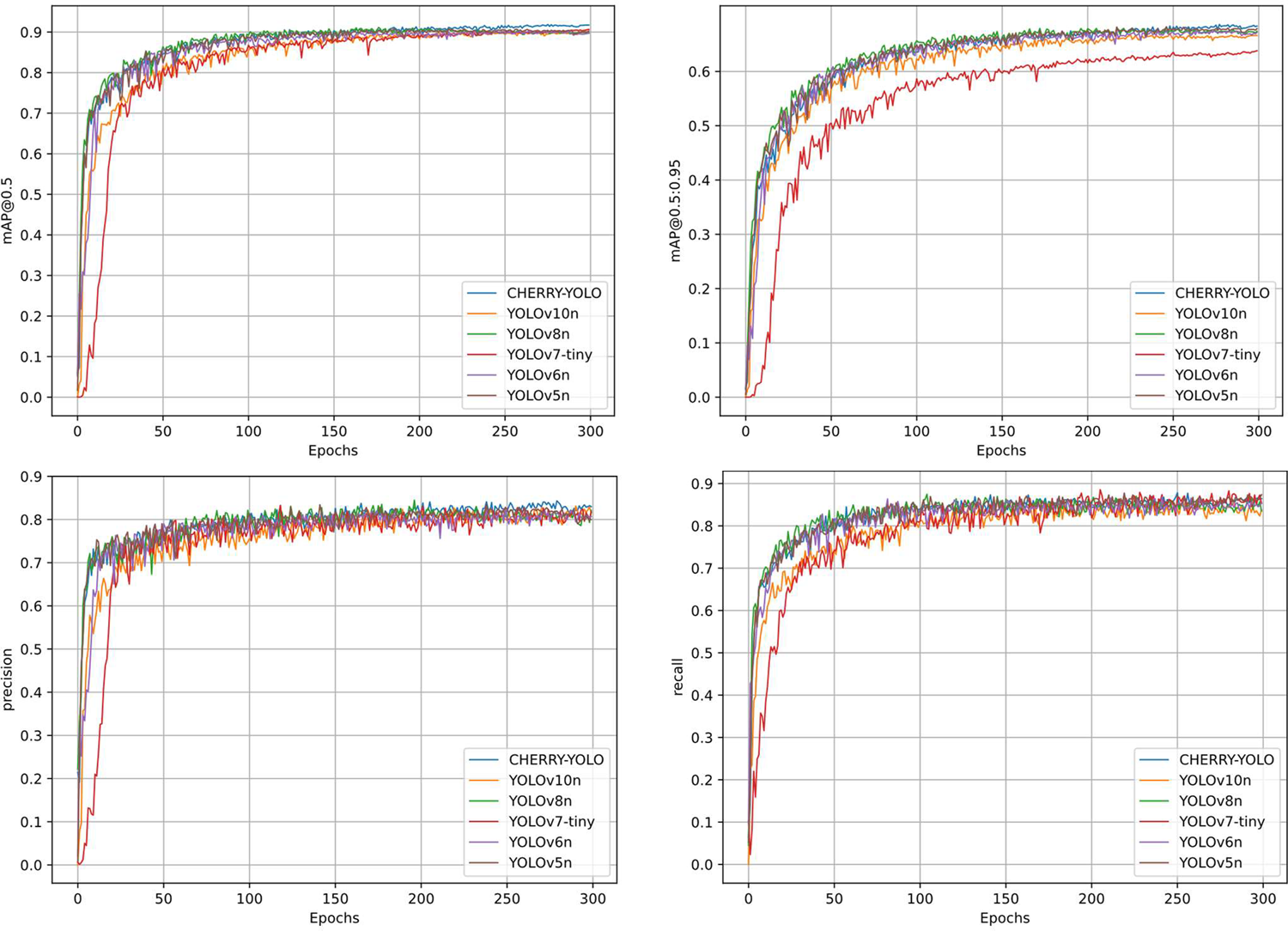

To comprehensively explore the performance indicators of the improved CHERRY-YOLO model and other models, this study conducts training and validation on the same dataset for the CHERRY-YOLO model and some lightweight versions of the YOLO series object detection networks (such as YOLOv5n, YOLOv6n, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv8n, and YOLOv10n). These lightweight versions

are selected for comparison because of their advantages in terms of the number of parameters, computational complexity, and inference speed, which represent the performance of their respective series in resource-constrained scenarios. Compared with these lightweight models, we can more comprehensively evaluate the improvements of the CHERRY-YOLO model in terms of its lightweight design and detection performance. The experimental results are shown in Table 2.

As shown in Table 2, the weight size, parameter size, and computational size of the CHERRY-YOLO model are the smallest compared with those of the YOLOv5n, YOLOv6n, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv8n, and YOLOv10n models, in which the weight size is reduced by 5.7, 42.53, 59.35, 20.63, and 13.79 percentage points, respectively; the parameter size is reduced by 10.85, 44.10, 60.67, 21.27, and 12.19 percentage points, respectively; and the computation size is reduced by 17.95, 45.76, 51.56, 20.99, and 21.95 percentage points, respectively. The CHERRY-YOLO model is higher than the other models in terms of precision, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95, in which the precision is improved by 1.8, 3.0, 1.8, 1.3, 3.0 percentage points over YOLOv5n, YOLOv6n, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv8n, and YOLOv10n, respectively, and mAP@0.5 improved by 1.3, 1.5, 1.2, 1.0, and 1.6 percentage points, and mAP@0.5:0.95 improved by 0.5, 1.1, 4.9, 0.6, and 1.7 percentage points, respectively; In terms of recall, the CHERRY-YOLO improves 0.3, 0.5, 0.4, and 0.6 percentage points over YOLOv5n, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv8n, and YOLOv10n, respectively, and is only 0.4 percentage points lower than YOLOv6n.

The graphs of the precision, recall, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95 of the CHERRY-YOLO and other models are shown in Figure 9. After the 200th round of iterations, the training results of various models basically converge, and the values of mAP@0.5, mAP@0.5:0.95, and precision of CHERRY-YOLO are higher than those of the other models.

Comparison of CHERRY-YOLO with other model’s metrics: (a) mAP@0.5, (b) mAP@0.5:0.95, (c) precision, (d) recall.

Comparison of heatmaps between the CHERRY-YOLO and YOLOv8n models

To better visualize how the CHERRY-YOLO model focuses on different target areas, and to understand its application capabilities, this study uses both the CHERRY-YOLO and YOLOv8n models to detect cherries in complex scenarios such as fruit overlap, branch-leaf occlusion, and small targets. The detection results are compared using GradCAM heatmaps (Figure 10), where the color intensity indicates the model's attention level in predicting targets; darker colors signify greater influence on the prediction.

Figure 10 shows that the YOLOv8n model does not pay enough attention to detection objects such as branch and leaf occlusions and small target fruits when detecting cherry fruits in complex scenes. In all three instances, the cherry targets are overlooked. In Example 3, the YOLOv8n model

also incorrectly focused on the cherry leaves. The areas that have not been noticed, or have been incorrectly noticed, are shown in the yellow box in the figure. However, when the detection results of the CHERRY-YOLO model are compared, the cherry targets in all three examples can be clearly identified, and there are no areas of incorrect focus. This intuitively demonstrates that the CHERRY-YOLO model can better locate and detect cherry fruit targets in complex scenes and has better detection abilities than the YOLOv8n model. This is attributed to its enhanced attention mechanism: channel attention suppresses occlusion interference and strengthens cherry-related feature channels, whereas spatial attention precisely locates small or overlapping fruits. Thus, the CHERRY-YOLO model outperforms YOLOv8n in detecting cherry fruits in complex scenarios.

Comparison of the detection results between the CHERRY-YOLO and YOLOv8n models

To show the detection performance of CHERRY-YOLO in this paper more intuitively, CHERRY-YOLO and the original YOLOv8n model are used to detect pictures containing ripe and unripe cherry fruits, as well as the presence of fruit overlap and branch and leaf occlusions; the detection results are shown in Figure 11. The yellow box represents a false detection, the blue box represents a missed detection, the white box represents a duplicate detection, the red box represents a ripe fruit, and the pink box represents an unripe fruit.

To assess the CHERRY-YOLO model's detection performance, three groups of cherry images with 42 valid targets were used in comparison tests against the original YOLOv8n model. The YOLOv8n model showed detection errors: 1 misdetection in Example 1, 2 missed detections in Example 2 due to an overlap and occlusion, and 1 duplicate detection in Example 3. Quantitative analysis revealed that among the 42 actual targets, YOLOv8n had 40 correct detections, 2 missed detections, 1 false detection, and 1 repeated detection, resulting in a 4.76% false-negative rate. These issues highlight its instability in complex scenarios. In contrast, the CHERRY-YOLO model achieved zero-error detection on the same dataset, demonstrating its superior accuracy and stability, thus validating its effectiveness for cherry fruit detection.

CONCLUSIONS

-

This paper proposes a lightweight cherry detection model based on an improved YOLOv8n. It replaces the bottleneck module in the original C2f with a partially convolution-based FasterNet Block module to achieve lightweighting while maintaining high detection accuracy. Additionally, inserting the CBAM attention mechanism between the SPPF and C2f-Faster modules in the backbone network enhances target feature extraction before multiscale feature map fusion, further improving the target detection accuracy.

-

To investigate the effects of the two improvement measures on model performance, this study conducted an ablation test. Compared with the original YOLOv8n, the CHERRY-YOLO model increased the precision, mAP@0.5, mAP@0.5:0.95, and recall by 1.3, 1.0, 0.6, and 0.4 percentage points, respectively. Moreover, it reduced the parameter size, computation size, and weight size by 21.27, 20.99, and 20.63 percentage points, respectively, achieving lightweighting while enhancing the detection accuracy.

-

Compared with those of YOLOv5n, YOLOv6n, YOLOv7-tiny, and YOLOv10n, the weights of CHERRY-YOLO were reduced by 5.7, 42.53, 59.35, and 13.79 percentage points, the numbers of parameters were reduced by 10.85, 44.10, 60.67, and 12.19 percentage points, and the sizes of the computations were reduced by 17.95, 45.76, 51.56, and 21.95 percentage points. Moreover, the precision, mAP@0.5, mAP@0.5:0.95, and recall were better overall than those of the YOLOv5n, YOLOv6n, YOLOv7-tiny, and YOLOv10n network models.

-

HERRY-YOLO outperforms the original YOLOv8n in complex natural scenarios such as occlusions, overlaps, and small-target detections. However, this study has limitations. On low-end hardware such as old mobile devices or embedded systems, its computational performance may suffer, reducing the real-time detection speed and increasing memory consumption, which could cause slowdowns or crashes. These issues underscore the need to further optimize the model for better cross-platform compatibility and performance in practical applications.

-

The CHERRY-YOLO model has broad application potential. Its effectiveness in complex cherry detection suggests that it can be adapted to detect other small fruits with similar challenges, such as strawberries, blueberries, and grapes, which often face occlusion, overlapping, and small-target issues. By leveraging its feature extraction and recognition mechanisms and adjusting the training dataset and model parameters, CHERRY-YOLO could become a versatile solution for various small-object detection tasks, extending its use beyond the cherry orchards.

REFERENCES

- Bai, Y., Yu, J., Yang, S., & Ning, J. (2024). An improved YOLO algorithm for detecting flowers and fruits on strawberry seedlings. Biosystems Engineering, 237, 1-12.

- Chen, J., Kao, S.-h., He, H., Zhuo, W., Wen, S., Lee, C.-H., & Chan, S.-H. G. (2023). Run, don't walk: chasing higher FLOPS for faster neural networks. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference On Computer Vision And Pattern Recognition.

- Chen, M., Chen, Z., Luo, L., Tang, Y., Cheng, J., Wei, H., & Wang, J. (2024). Dynamic visual servo control methods for continuous operation of a fruit harvesting robot working throughout an orchard. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 219, 108774.

- Gai, R., Chen, N., & Yuan, H. (2023). A detection algorithm for cherry fruits based on the improved YOLO-v4 model. Neural Computing and Applications, 35 (19), 13895-13906.

- Gao, Y., Li, Z., Li, B., & Zhang, L. (2024). YOLOv8MS: Algorithm for Solving Difficulties in Multiple Object Tracking of Simulated Corn Combining Feature Fusion Network and Attention Mechanism. Agriculture, 14 (6), 907.

- Guo, M.-H., Xu, T.-X., Liu, J.-J., Liu, Z.-N., Jiang, P.-T., Mu, T.-J.,…Hu, S.-M. (2022). Attention mechanisms in computer vision: A survey. Computational visual media, 8 (3), 331-368.

- Islam, M. S., Scalisi, A., O'Connell, M. G., Morton, P., Scheding, S., Underwood, J., & Goodwin, I. (2022). A ground-based platform for reliable estimates of fruit number, size, and color in stone fruit orchards. HortTechnology, 32 (6), 510-522.

- Ji, W., Zhao, D., Cheng, F., Xu, B., Zhang, Y., & Wang, J. (2012). Automatic recognition vision system guided for apple harvesting robot. Computers & Electrical Engineering, 38 (5), 1186-1195.

- Li, H., Gu, Z., He, D., Wang, X., Huang, J., Mo, Y., Li P, Huang Z., & Wu, F. (2024a). A lightweight improved YOLOv5s model and its deployment for detecting pitaya fruits in daytime and nighttime light-supplement environments. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 220, 108914.

-

Li, M., Xiao, Y., Zong, W., & Song, B. (2024b). Detecting chestnuts using improved lightweight YOLOv8. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering, 40 (1), 201 - 209. https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.202309185

» https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.202309185 -

Li, Z., Jiang, X., Shuai, L., Zhang, B., Yang, Y., & Mu, J. (2022). A Real-Time Detection Algorithm for Sweet Cherry Fruit Maturity Based on YOLOX in the Natural Environment. Agronomy, 12 (10), 2482. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4395/12/10/2482

» https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4395/12/10/2482 - Liakhov, D., Mityugov, N., Gracheva, I., Kopylov, A., Seredin, O., & Tiras, K. P. (2022). Scanned Plant Leaves Boundary Detection in the Presence of a Colored Shadow. Pattern Recognition and Image Analysis, 32 (3), 575-585.

- Lin, Y., Huang, Z., Liang, Y., Liu, Y., & Jiang, W. (2024). AG-YOLO: A rapid citrus fruit detection algorithm with global context fusion. Agriculture, 14 (1), 114.

- Meng, F., Li, J., Zhang, Y., Qi, S., & Tang, Y. (2023). Transforming unmanned pineapple picking with spatio-temporal convolutional neural networks. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 214, 108298.

- Mirhaji, H., Soleymani, M., Asakereh, A., & Mehdizadeh, S. A. (2021). Fruit detection and load estimation of an orange orchard using the YOLO models through simple approaches in different imaging and illumination conditions. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 191, 106533.

- Niu, Z., Zhong, G., & Yu, H. (2021). A review on the attention mechanism of deep learning. Neurocomputing, 452, 48-62.

- Sekharamantry, P. K., Melgani, F., & Malacarne, J. (2023). Deep learning-based apple detection with attention module and improved loss function in YOLO. Remote Sensing, 15 (6), 1516.

- Shan, X., Shen, Y., Cai, H., & Wen, Y. (2022). Convolutional neural network optimization via channel reassessment attention module. Digital Signal Processing, 123, 103408.

- Shuai, L., Mu, J., Jiang, X., Chen, P., Zhang, B., Li, H., Wang Y., & Li, Z. (2023). An improved YOLOv5-based method for multi-species tea shoot detection and picking point location in complex backgrounds. Biosystems Engineering, 231, 117-132.

-

Song, H., Shang, Y., & He, D. (2023). Review on Deep Learning Technology for Fruit Target Recognition. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery, 54 (01), 1 - 19. https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.1964.S.20221008.1624.019

» https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.1964.S.20221008.1624.019 - Sun, H., Wang, B., & Xue, J. (2023). YOLO-P: An efficient method for pear fast detection in complex orchard picking environment. Frontiers in plant science, 13, 1089454.

- Wang, W., Shi, Y., Liu, W., & Che, Z. (2024). An unstructured orchard grape detection method utilizing YOLOv5s. Agriculture, 14 (2), 262.

- Woo, S., Park, J., Lee, J.-Y., & Kweon, I. S. (2018). Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV)

- Xiao, B., Nguyen, M., & Yan, W. Q. (2024). Fruit ripeness identification using YOLOv8 model. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 83 (9), 28039-28056.

- Yang, H., Liu, Y., Wang, S., Qu, H., Li, N., Wu, J., Yan, Y., Zhang, H., Wang, J., & Qiu, J. (2023). Improved Apple Fruit Target Recognition Method Based on YOLOv7 Model. Agriculture, 13 (7), 1278.

-

Zhang, Z., GUO, S., Liu, G., Li, S., & ZHANG, Y. (2022). Cherry Fruit Detection Method in Natural Scene Based on Improved YOLO v5. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery, 53(S1), 232-240. https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.1964.S.20220901.1353.018

» https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.1964.S.20220901.1353.018 - Zhong, Z., Yun, L., Cheng, F., Chen, Z., & Zhang, C. (2024). Light-YOLO: A lightweight and efficient YOLO-Based deep learning model for mango detection. Agriculture, 14 (1), 140.

-

FUNDING:

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China, grant number 2023YFD2001100.

Edited by

-

Area Editor:

Gizele Ingrid Gadotti

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

15 Sept 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

05 Aug 2024 -

Accepted

17 June 2025

CHERRY-YOLO: LIGHTWEIGHT MODEL FOR CHERRY DETECTION BASED ON IMPROVED YOLOv8n

CHERRY-YOLO: LIGHTWEIGHT MODEL FOR CHERRY DETECTION BASED ON IMPROVED YOLOv8n