ABSTRACT

The rotary buryig blade roller (RBBR) is a tillage tool that can both break up soil and bury straw. However, in previous experiments, it was found that the configuration of rotary blades on RBBR will significantly affect its tillage quality. To achieve the optimal structure of RBBR, this study optimized the configuration of rotary blades on RBBR. Additionally, the tillage performance of different RBBRs was evaluated using the Discrete Element Method (DEM). The results showed that after removing loose soil, the optimized RBBR (SR-8-1) achieved a flatter bottom of tilled layer compared to the previous RBBR (SR-6 and SR-9). Specifically, the calculated bottom evenness after tillage decreased by 40.49% and 40.65%, respectively. Furthermore, upon measuring tillage depth, stability coefficient of tillage depth increased by 5.12% and 3.84%. The exported average axial force from the software decreased by 65.72% and 80.39%. The comparison of field test and simulation showed that SR-8-1 was superior to SR-6 in all tillage parameters except power. Therefore, due to the advantages of SR-8-1 in terms of tillage performance, it is better able to meet the tillage needs than other structures.

rotary burying blade roller; rotary blade; configuration mode; DEM; tillage performance

Introduction

Soil tillage is an important link in agricultural production and lays a good foundation for subsequent agricultural technology operations such as sowing (Khan et al., 2024; Islam et al., 2023). The quality of soil tillage is closely related to the performances of tillage tools. Therefore, researchers have conducted relevant studies on different tillage tools, such as rotary tiller (Du et al., 2022), subsoiler (Zhang et al., 2022), moldboard plow (Kim et al., 2021).

As the most commonly used soil tillage tool, the rotary tiller can effectively crush soil and straw and mix them together (Mairghany et al., 2019). Some improvements have also been made to highly standardized rotary blades, with the aim of improving operating performance of rotary tiller. Researchers have reported on a new type of blade installed on a reverse rotating rotary tiller, which exhibits superior weed control and burial performance compared to traditional rotary tiller (Salokhe & Ramalingam, 2002). To reduce the energy requirements of rotary blades, three types of blades were developed using computer technology, ultimately identifying the RC-type blade as having better performance and lower power (Asl & Singh, 2009). The working effect of rotating straight blades with different cutting edges was studied, and it was recommended to use blade with internal chamfer for strip tillage (Matin et al., 2016).

To better achieve the objectives of breaking soil and burying straw, the research group designed a spiral horizontal blade to cooperate with the current structure of rotary blade and formed a new type of RBBR (Zhang et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2019b). However, determining the optimal configuration between the rotary blades and the spiral horizontal blades remains an issue to be addressed.

The unclear configuration of spiral horizontal blades and rotary blades can lead to two problems. The first is imbalance of axial force on single section RBBR. That is, the axial reaction force of soil on spiral horizontal blades and rotary blades cannot offset each other, which may increase the vibration of machine and affect its life (Xiong et al., 2018). The second is that there are sometimes obvious uneven areas at the bottom of tillage layer (mainly under the condition of clay loam). According to the measurement, the width of convex part was approximately the distance between two adjacent rotary blades within the axial range, and the height was approximately the difference between rotary radius of rotary blade and spiral horizontal blade. Some researchers also found that the ditch bottom was uneven after tillage, and there were missing tillage and ridge bulges when they used rotary blade to conduct the test (Ji et al., 2012). Another researchers found a similar situation when using an external chamfer blade in a strip tillage experiment (Matin et al., 2016). This phenomenon will reduce tillage quality and affect root development of subsequent crops. The main reason for this phenomenon was that one spiral horizontal blade corresponded to two rotary blades within its width, and the above problem would occur if the axial spacing between the two rotary blades was too large. Therefore, to improve tillage quality of RBBR, it was necessary to optimize the configuration of rotary blades. Theoretical calculations can effectively aid in analyzing this problem, while the adoption of Discrete Element Method (DEM) as a means to evaluate the design quality of agricultural machinery has become an increasingly popular trend.

The DEM has become an important means for performing rapid research on agricultural machinery, especially on soil tillage tools (Wang et al., 2020). Based on DEM, some researchers simulated force acting on a moldboard plow in clay soil, and the results showed a good agreement with actual situation (Makange et al., 2020). The installation parameters of three subsoiler wings were optimized, with relative errors below 15% under optimal parameters (Wang et al., 2019). The influences of various factors on draught force, vertical force, and drawbar power of a vibrating digging shovel were simulated (Awuah et al., 2022).

Aiming at the problem that the configuration of rotary blades on RBBR significantly affects tillage quality, this study conducted a theoretical reanalysis and redesign of blades configuration on RBBR to achieve better working performance. The superiority of the optimized RBBR over two RBBRs before optimization was studied using DEM. Finally, the accuracy of DEM simulation and rationality of the optimized RBBR were verified through field test.

Material and methods

Structure of RBBR

RBBR is composed of 6 sections, of which one section is shown in Figure 1, and the other sections are same or symmetrical (in this paper, one section is taken as the research object). This section is mainly composed of machetes, spiral horizontal blades, rotary blades, cutter heads and a blade shaft. RBBR is usually contained 3 spiral horizontal blades paired with 6 rotary blades, and occasionally 9 rotary tillage blades (Zhu et al., 2020). During the operation of RBBR, the continuous cutting and throwing of straw and soil are mainly carried out by rotary blades and spiral horizontal blades to achieve crushing, mixing, and burying of straw and soil.

Structure of RBBR: (1) machete; (2) spiral horizontal blade; (3) rotary blade; (4) cutter head; (5) blade shaft.

Optimization of rotary blades configuration

In traditional rotary tiller, only the arrangement of rotary blade needs to be considered, while the arrangement of a variety of blades, such as spiral horizontal blade and rotary blade, needs to be considered in the configuration of RBBR. As spiral horizontal blade and rotary blade are set at a certain angle from the forward direction, both have axial throwing effects on soil. As shown in Figure 1, the research group has shown that soil thrown by blade was approximately along the normal direction of its surface. Rotary blade and spiral horizontal blade throw soil at the right rear and left rear of RBBR, respectively (Du et al., 2022). Obviously, the reason for first problem is that the volume of soil thrown by spiral horizontal blades and rotary blades is different in the left and right directions, resulting in different axial forces. Although research group studied the throwing direction of soil, the amount of soil thrown by each blade and the blade configuration were not clear. Therefore, to improve the tillage performance of RBBR, the amount of soil thrown axially by spiral horizontal blades and rotary blades should be balanced as much as possible under the premise of maintaining proper spacing of rotary blades.

Each section of RBBR contains three spiral horizontal blades, which are alternately arranged with rotary blades. Therefore, one spiral horizontal blade is taken as a reference and the corresponding number of rotary blades needed are obtained by calculating the amount of soil it throws axially.

The shape of soil slice cut by rotary tillage tools is shown in Figure 2. The volume of soil slice is mainly related to the cutting pitch (S), cutting width (b0) and tillage depth (h). Its volume can be approximately calculated by [eq. (1)], as follows:

Soil slice cut by rotary tillage tools. The green dotted line refers to position where the next adjacent rotary tillage tool in the same rotation plane cuts soil.

Where:

V is volume of soil slice, mm3;

S is soil cutting pitch, mm;

b0 is cutting width, mm;

h is tillage depth, mm.

The soil cutting pitch can be expressed by eq. (2), as follows:

Where:

vm is forward speed of rotary tillage tools, mm∙s-1;

Z is number of blades in same rotary plane;

ω is rotating speed of cutter roller, rad∙s-1.

Substitute [eq. (2)] into (1) to obtain the following:

Assuming that the amount of soil thrown axially by one spiral horizontal blade can balance the amount of soil thrown in the reverse direction by n rotary blades, the amount of soil thrown axially by spiral horizontal blade can be expressed as follows:

Where:

VS is amount of soil thrown axially by one spiral horizontal blade, mm3;

hS is tillage depth of spiral horizontal blade, mm;

n is number of rotary blades;

dR is cutting width of one rotary blade, mm;

φS is soil throwing angle of spiral horizontal blade, (°).

The amount of soil thrown axially by n rotary blades can be expressed as follows:

Where:

VR is amount of soil thrown axially by n rotary blades, mm3;

hR is tillage depth of rotary blade, mm;

φR is soil throwing angle of rotary blade, (°).

When the amount of soil thrown axially by one spiral horizontal blade and n rotary blades is balanced with each other, that is, VS=VR, the calculation can be obtained as follows:

Under normal tillage conditions, hR is 150 mm, hS is 115 mm, b0 is 295 mm, and dR is 51.3 mm. The actual measured φR is 30°, and φS is 26.4°. If the above data are entered into [eq. (6)], n≈2.33. This indicates that within a single section, the axial throwing effect generated by three horizontal blades requires the configuration of 7 rotary blades to counteract. However, 7 rotary blades cannot achieve circumferential uniform distribution. Moreover, the original configuration with 6 rotary blades in one section on blade roller has been validated to result in insufficient flatness at the bottom of tillage layer. Based on the above considerations, 2 rotary blades are added to one section, and the rotation direction of one is to left and one is to right. Not only does this configuration not increase the amount of soil thrown axially by rotary blades, but it also increases the number of rotary blades. Additionally, 3 rotary blades are evenly distributed between two adjacent spiral horizontal blades, as shown in Figure 3.

Optimized RBBR (SR-8-1): (a) the structures of three types of RBBR, (b) the physical object of the completed SR-8-1 after processing.

Soil cutting range of rotary blades

There are three main research objects in paper (Figure 3a), namely, the previous single blade roller equipped with 6 co-rotating blades (SR-6), a single blade roller equipped with 9 co-rotating blades (SR-9) and an optimized single blade roller equipped with 8 co-rotating blades and 1 counter-rotating blade (SR-8-1).

The direct soil cutting range of rotary blades during the operation of three RBBRs is shown in Figure 4. The shaded part represents soil range that rotary blades can directly cut, and the blank part indicates soil range that rotary blades cannot directly cut. Figure 4a and Figure 4b show that the width of soil that can be directly cut by rotary blades within the width range of SR-6 and SR-9 are 2dR (102.6 mm) and 3dR (153.9 mm), respectively. The soil range that cannot be directly cut (the blank area in the figure) is relatively wide, which may lead to unevenness at the bottom of the tillage layer. Figure 4c shows the soil width that can be directly cut by rotary blades within the width range of optimized SR-8-1 is 4dR-10 (195.2 mm), which is an increase of 90.3% and 26.8% compared with SR-6 and SR-9, respectively. Obviously, the cutting range of SR-8-1ʼs rotary blades is greatly increased, and the soil belt that cannot be directly cut is narrow. Moreover, the driving effect of adjacent rotary blades can disturb the untilled soil belt to avoid the unevenness at the bottom of tillage layer.

Soil cutting range of rotary blades on the following three RBBRs: (a) SR-6, (b) SR-9, (c) SR-8-1.

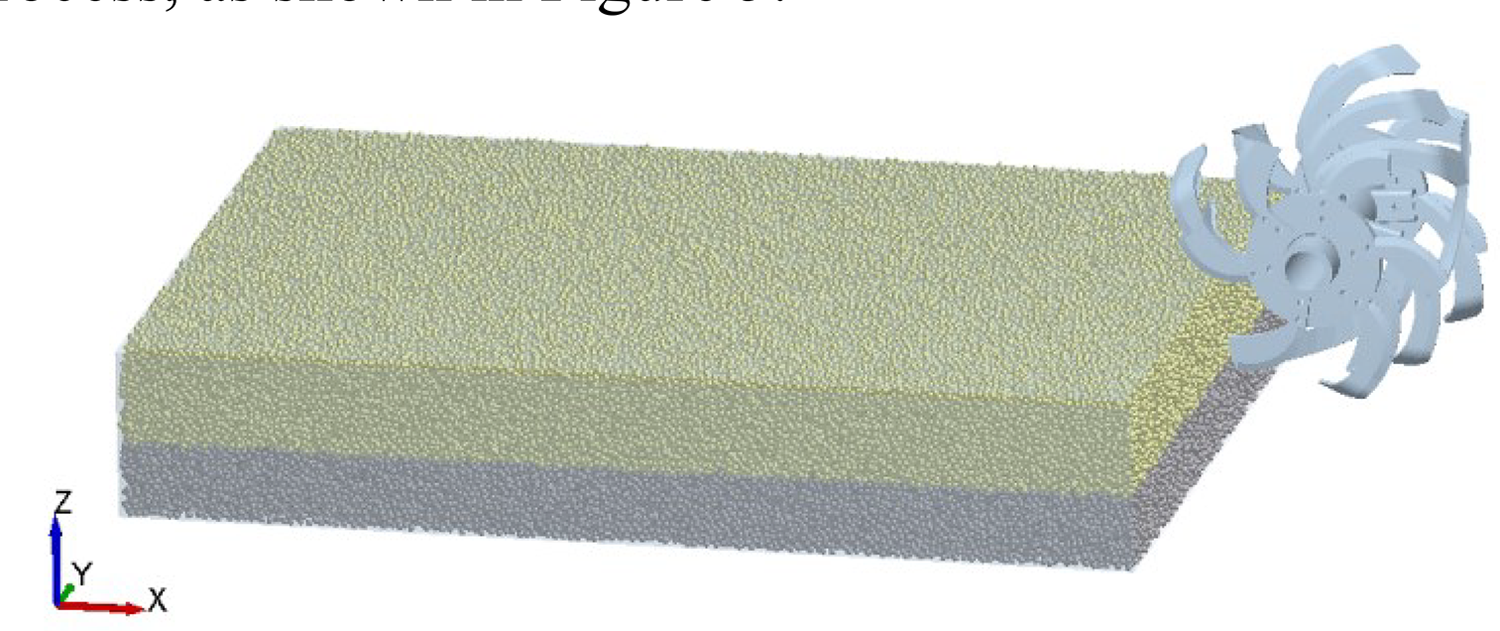

DEM simulation

To verify the tillage performances of three RBBRs, a three-dimensional simulation model consisting of RBBRs, a soil bin and soil particles was developed using the DEM software EDEM. The model of RBBRs was drawn in 3D drawing software Pro/Engineer and imported into EDEM. The length, width and height of virtual soil bin were 1500 mm, 1000 mm and 280 mm, respectively. The reason for the large size of soil bin was to prevent the side and bottom surfaces of the virtual soil bin from affecting the tillage effect of RBBRs during the simulation process, as shown in Figure 5.

Agricultural machinery simulation contacting soil typically models particles as homogeneous spheres, with particle size and quantity significantly affecting computational duration (Aikins et al., 2021; Zeng et al., 2020). Therefore, the soil particle radius was 5 mm for this DEM simulation (Fang et al., 2016). In combination with the soil characteristics of clay loam in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, a two-layer soil model was established for tillage layer soil (TS, 0-150 mm) and bottom layer soil (BS, 150-280 mm), generating approximately 316000 soil particles in total. The two layers of soil particles are represented by different colors, as shown in Figure 5.

According to the actual situation of clay loam in the test site, combined with the previous test parameter measurement, this simulation sets the contact model between soil and RBBR as Hertz-Mindlin (no slip) and the contact model between soil particles as Hertz-Mindlin with JKR (Zhou et al., 2019a). The HM-JKR model takes into account the influence of the cohesive force between wet particles on the particle movement law. It is a cohesive contact model that is suitable for simulating the cohesion between soil particles (Feng et al., 2021).

The model parameters in the EDEM software mainly include material parameters and contact parameters. The material parameters mainly include Poisson's ratio, density and shear modulus. The contact parameters mainly include the coefficient of restitution, coefficient of static friction and coefficient of rolling friction. The material parameters and contact parameters for this simulation were partially obtained through previous experimental measurements and calibrations conducted by the research group, including parameters such as the shear modulus of soil, coefficient of static friction of soil-soil, and coefficient of restitution of soil-steel and so on (Du et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2019a; Zhou et al., 2020). Additionally, some of the parameters were obtained from references on similar soils, such as the density of soil, density of steel, and shear modulus of steel and so on (Awuah et al., 2022; Li et al., 2016). The TS and BS soil particles exhibit certain differences in simulation parameters such as friction coefficient and surface energy. Detailed model simulation parameters are presented in Table 1.

Methods and data processing

Discrete element simulations were conducted using three RBBRs at three different tillage depths (120 mm, 150 mm, and 180 mm). Simultaneously set the forward speed was 0.43 m/s and the rotary speed was 327 r/min. The Rayleigh time step was set to 8.79×10-5 s, with the simulation time step defined as 10% of this value.

The bottom profiles presented a certain degree of unevenness after tillage with different RBBRs. To more clearly quantify the effects of different RBBRs on the bottom profiles after tillage, the concept of bottom evenness after tillage (BET) was introduced here with reference to the measurement method of surface evenness after tillage in GB/T 5668-2017 (Chinese Standard Committee, 2017). The calculation method is as follows:

Where:

ai is height of the ith measuring point, mm;

a is the average height of measuring point, mm;

n is number of measuring points.

Obviously, similar to the surface evenness after tillage, the smaller the BET value is, the flatter the bottom after tillage is, and the better the tillage quality is.

The actual average tillage depth (HSR-N) reflects the ability of RBBR to achieve the predetermined tillage depth. The stability coefficient of tillage depth (STD) is an important indicator to describe the change degree of the actual tillage depth (Chinese Standard Committee, 2017; Zhang et al., 2015). Its calculation method is as follows:

Where:

ST is standard deviation of tillage depth under working conditions, mm;

Hi is the depth of ith measuring point, mm;

HSR-N is actual average tillage depth of each RBBR, mm;

m is number of measurement points;

VC is variation coefficient of tillage depth under working conditions, %.

The BET, HSR-N, and STD were measured and calculated at 30 randomly selected measurement points within the time frame corresponding to the stable operating range of the RBBR (4.5~7.5 s).

Methods of field test

To test the actual tillage effect of RBBR and the accuracy of simulation model, field tests of SR-6 and SR-8-1 were conducted at the Modern Agricultural Science and Technology Experimental Base of Huazhong Agricultural University in Wuhan, China. The previous crop in the experimental field is rapeseed, with less straw residue, which has a relatively small impact on the tillage characteristics of RBBRs detection. Soil analysis identified silty clay loam texture in the experimental field (31 ± 2% clay, 63 ± 4% silt, 6 ± 2% sand). Actual measurements have shown that within a depth range of 150 cm, the soil cone index is 1515.5 kPa, the soil moisture content is 16.3%, and the dry bulk density of soil is 1347.6 kg·m⁻3. During the test, a full-size RBBR was used (Figure 3b), that is, the machine contains 6 sections of SR-8-1. Therefore, the final data needs to be divide by 6 to correspond to the DEM simulation results. The operation parameters of field test were set as follows: forward speed is 0.43 m/s, rotary speed is 327 r/min, and tillage depth is 150 mm. Each test was repeated three times, and the average value was taken as result. The data collection device included various sensors and dynamic data collector, as shown in Figure 6. The sensors are capable of capturing real-time data such as the torque, rotational speed, and draught force of the RBBR, and instantly transmits this data to a dynamic data collector. Subsequently, the dynamic data collector sends the data to a receiving computer via wireless transmission. On the receiving computer, the accompanying software, based on preset algorithms, converts the acquired data into power in real time. The specific formula for calculating power is as follows:

Where:

P is power of RBBR, kW;

T is torque of RBBR, N∙m;

N is rotational speed of RBBR, r/min.

Results and discussion

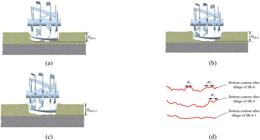

Soil cross-sectional profile

The cross-sectional profile formed after soil cutting by RBBR serves as a crucial indicator for evaluating its degree of soil disturbance, which in turn is one of the important dimensions for evaluating its tillage performance (Wang et al., 2020; Song et al., 2022). During the post-processing phase of the discrete element simulation, a soil slice with a thickness of 50 mm was extracted along the advancing direction of the RBBR for the purpose of analyzing soil disturbance. Taking a tillage depth of 150 mm as an example, the processes of SR-6, SR-9, and SR-8-1 cutting through soil and the movement of soil particles are shown in Figure 7. The cross-sectional profiles of SR-6, SR-9, and SR-8-1 at the moment they have completely traversed the slice are separately shown in Figure 8. As evident from the figures, these three RBBRs primarily produce significant disturbance effects within their designed tillage widths, with relatively minor impacts observed outside these widths. This finding aligns with previous research results on other tillage tools (Li et al., 2016; Matin et al., 2014, 2016). The primary reason for this is that the machetes positioned on both sides of spiral horizontal blades effectively cut soil particles to form neat trench walls, thereby effectively limiting the influence of spiral horizontal blades and rotary blades on soil particles outside these walls.

The process of cutting and throwing soil with a RBBR and the soil particle movement: (a) SR-6, (b) SR-9, (c) SR-8-1.

The cross-sectional profiles of three RBBRs as they completely pass through the slice when the tillage depth is 150mm: (a) SR-6, (b) SR-9, (c) SR-8-1, (d) The bottom contours extracted for enlargement.

Three bottom profiles are extracted as shown in Figure 8d, and it is evident that there are significant differences among the three profiles. The bottom profile after tillage with SR-6 shows an overall undulating state. The soil cutting process of SR-6 in Figure 7a also reveals that at 7.29~7.31 seconds, the two rotary blades and spiral horizontal blade sequentially enter the soil to cut it. Due to the excessively large axial spacing between the two rotary blades, a prominent bulge, namely the area with width W1, is left between them. At 7.32 s, due to the lack of disturbance of rotary blades on the right side, only spiral horizontal blades are able to cut through soil, leaving an area with width W2. The bottom profile after tillage with SR-9 shows an overall state of being higher on both sides and lower in the middle. There is also a bulge with width W3 on its right side, but W3 is significantly smaller than W2. Compared to SR-6 and SR-9, the bottom profile after tillage with SR-8-1 is relatively flat overall. Figure 7c shows that during 7.30~7.32 s, the reverse rotary blade on the right side cuts and throws soil, so there is no obvious bulge on the right side. The mutual disturbance of adjacent rotary blades with appropriate spacing to soil during operation can basically realize soil tillage within the entire range. This is similar to the research results of Matin et al. (2016). The above analysis demonstrates that the bottom profile after tillage with SR-8-1 was obviously better than those obtained with SR-6 and SR-9. Therefore, to avoid the problem of unevenness at the bottom of tillage layer, SR-8-1 should be used as often as possible.

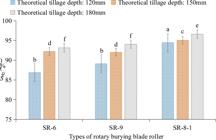

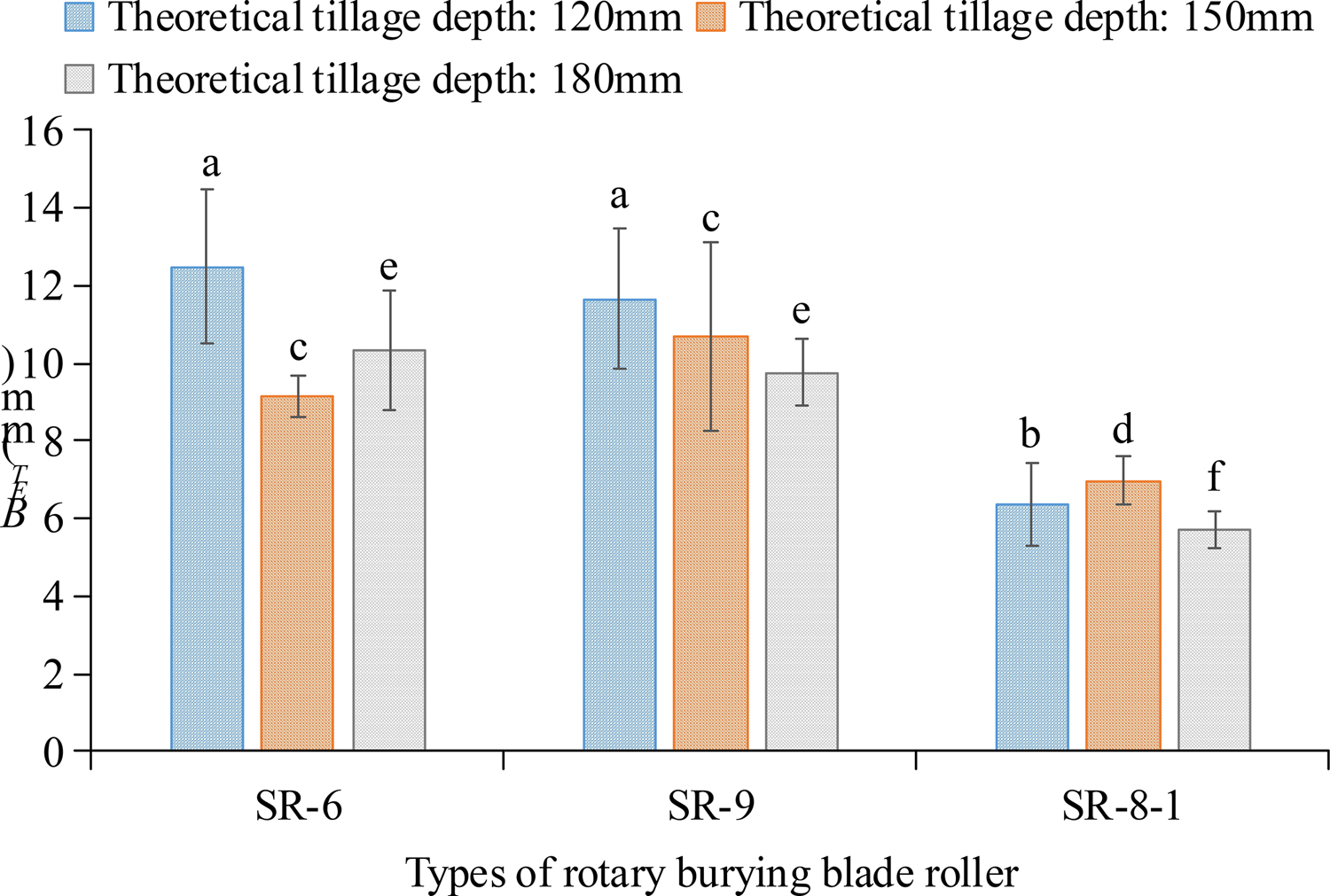

Bottom evenness after tillage

The BET results of three RBBRs under different tillage depths are shown in Figure 9. Under the same theoretical tillage depth, the BET of SR-8-1 had a significant effect on SR-6 and SR-9, while SR-6 and SR-9 had no significant effects (Figure 9). Obviously, the BET results after tillage with three RBBRs presented different characteristics. With the increase in tillage depth from 120 mm to 180 mm, the BET of SR-6 first decreased and then increased; the BET of SR-9 showed a decreasing trend; and the BET of SR-8-1 showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. Although BET changes of three RBBRs were different, the values of SR-6 and SR-9 were relatively close, while SR-8-1 was obviously smaller than the former two.

Bottom evenness after tillage (BET) of three RBBRs under different tillage depths. The means followed by different letters are significantly different according to Duncan’s multiple range test at the significance level of 0.05; the error bars are standard deviations.

The average BET values for SR-6 and SR-9 at three tillage depths were 10.67 mm and 10.70 mm, respectively, while SR-8-1 had an average BET value of 6.35 mm, which represented a significant decrease of 40.49% and 40.65% compared to SR-6 and SR-9, respectively. The magnitude of this decrease was notable. This showed that the bottom obtained after tillage with SR-8-1 was flatter. Matin et al. (2014) believed that the flat U-shaped bottom had more loose soil. Ji et al. (2012) reported that it was more suitable for later sowing if there was no obvious bulge at the bottom after tillage. Therefore, SR-8-1 should be used preferentially in the case of higher requirements for the quality of the bottom tillage layer.

Actual average tillage depth and stability coefficient of tillage depth

The HSR-N and STD of different RBBRs under the conditions of three theoretical tillage depths are shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11, respectively.

Actual average tillage depth (HSR-N) of different RBBRs under three theoretical tillage depth. The means followed by different letters are significantly different according to Duncan’s multiple range test at the significance level of 0.05; the error bars are standard deviations.

Stability coefficient of tillage depth (STD) of different RBBRs under three theoretical tillage depth. The means followed by different letters are significantly different according to Duncan’s multiple range test at the significance level of 0.05; the error bars are standard deviations.

The HSR-N of three RBBRs did not reach the set values (Figure 10). This was mainly related to the unevenness of the bottom. Under the same theoretical tillage depth, the HSR-N of SR-6 had a significant effect relative to SR-9 and SR-8-1, while SR-9 and SR-8-1 had no significant effects. The HSR-N results of SR-6, SR-9 and SR-8-1 all showed increasing trends under any theoretical tillage depth. Compared with SR-6 and SR-9, the HSR-N of SR-8-1 increased by 20.23% and 6.61%, respectively, when the theoretical tillage depth was 120 mm; HSR-N increased by 19.16% and 5.28%, respectively, when the theoretical tillage depth was 150 mm; and HSR-N increased by 12.12% and 3.59%, respectively, when the theoretical tillage depth was 180 mm. Obviously, the HSR-N of SR-8-1 (113.92 mm, 140.00 mm and 168.40 mm, respectively) had the smallest deviation from the theoretical tillage depth (5.07%, 6.67% and 6.44%, respectively). Therefore, SR-8-1 was better than SR-6 and SR-9 in achieving the predetermined tillage depth. Although the values of three RBBRs at the maximum tillage depth were almost the same, the bulges at the bottom obtained with SR-6 and SR-9 had a greater impact on the actual average tillage depth. Ji et al. (2012) also found a similar phenomenon in the test.

Under the same theoretical tillage depth, the STD of SR-8-1 had a significant effect on SR-6 and SR-9, while SR-6 and SR-9 had no significant effects (Figure 11). Obviously, the STD of SR-8-1 was better than that of SR-6 and SR-9 under any theoretical tillage depth, and the improvement effect was significant. The average STD of SR-8-1 under the three theoretical tillage depths was 95.35%, which was 5.12% and 3.84% higher than those of SR-6 (90.71%) and SR-9 (91.69%), respectively. The STD of any type of RBBR showed an increasing trend with increasing theoretical tillage depth. The STD of the three RBBRs reached the minimum and maximum when the theoretical tillage depths were 120 mm and 180 mm, respectively. The main reason may be that the deeper the tillage depth was, the greater the attraction between soil particles was. During the tillage process, the interactions between rotary blades and soil particles improved the uncultivated area at the bottom. Kataoka & Shibusawa (2002) also pointed out that the compressive stress and shear stress generated when rotary blade was cutting the soil will cause cracks in soil, which will expand to the uncultivated area along with the movement of the blade tip, thus improving the stability of tillage depth in the entire area.

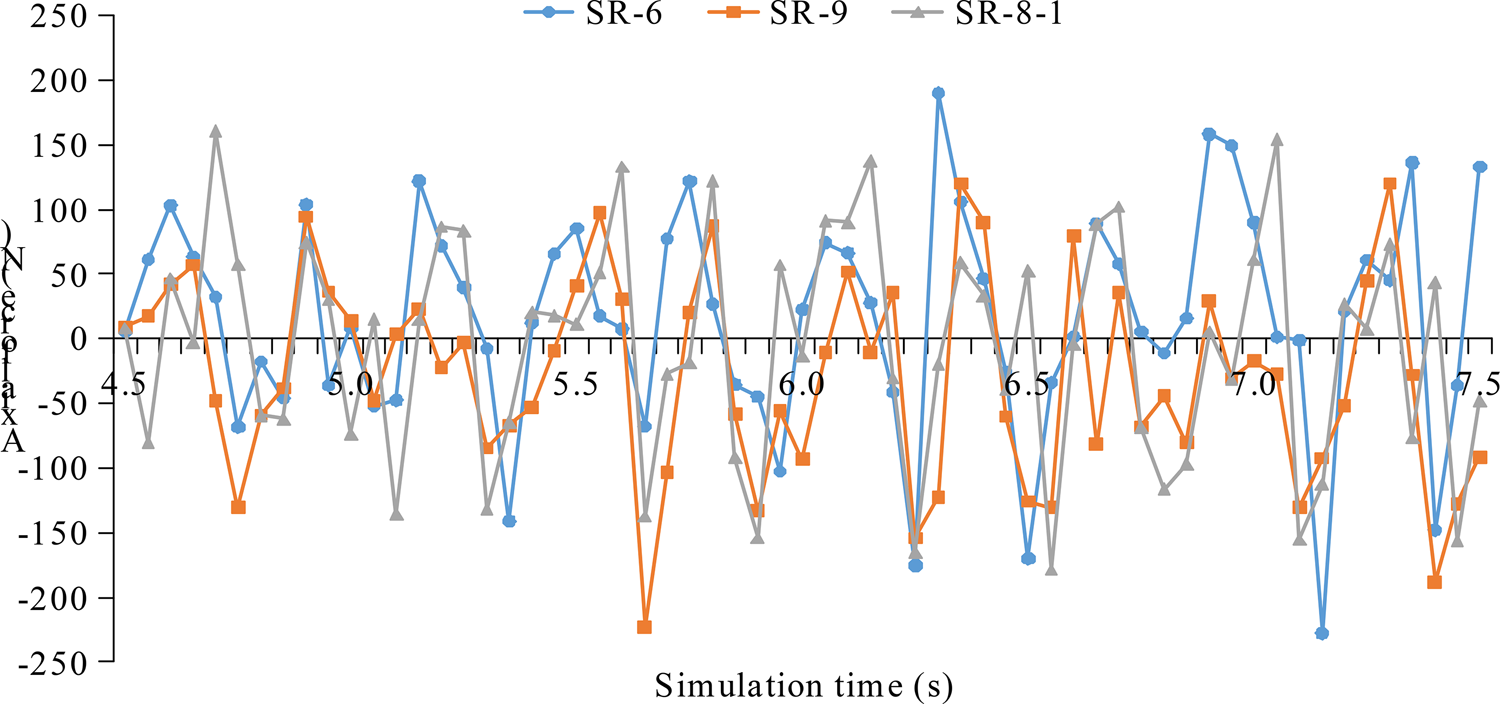

Axial force

In the coordinate system setup of the simulation model (Figure 5), the direction of the axial force aligns with the Y-axis. Utilizing the post-processing capabilities of the EDEM software, by simply selecting the RBBR as the output object, one can directly export the force data along the Y-axis direction for the RBBR over any specified time period. These data represent the axial forces experienced by the RBBR. During the simulation process, the period from 0~4 s is allocated for the generation and stabilization of soil particles, while the period from 4~8 s is designated for the operation of the RBBR. Specifically, the RBBR fully enters the virtual soil bin at 4.5 s, marking the commencement of its stable operation; after 7.5 s, the RBBR begins to exit the soil bin. Therefore, the interval from 4.5~7.5 s is selected as the stable simulation time. The axial force data for the three RBBRs are exported, and their variation trends are shown in Figure 12.

Because the operation parameters were the same, the axial force variation trends of three RBBRs were relatively consistent in a stable simulation period, and the axial force always alternated between positive and negative (Figure 12). That is, when RBBR was operating, the force along the width (Y-axis) direction changed back and forth between left and right. This was mainly because the spiral horizontal blades and rotary blades entered the soil alternately during the tillage process of RBBR. The soil being cut and thrown to the side exerted opposite forces on spiral horizontal blades and rotary blades, which led to the fluctuation of the axial force of RBBR in a certain range. Some scholars' tests on a single rotary blade have proven that the soil only produces a reaction force in the same direction on its side (Fang et al., 2016; Xiong et al., 2018).

The positive and negative axial forces represent the direction of the force exerted by the soil on RBBR. From the coordinate system of the DEM in Figure 5, it can be seen that the positive axial force of RBBR was mainly the force exerted by the soil being cut on spiral horizontal blades, while the negative axial force was mainly the force exerted on rotary blades. The average axial force of three RBBRs reflected the effects of their rotary blade configurations. The average axial force for SR-6 was 16.16 ± 84.65 N, for SR-8-1 it was -5.54 ± 87.44 N, and for SR-9 it was -28.25 ± 77.49 N. Statistical significance testing revealed that the average axial force of SR-8-1 showed a significant difference compared to SR-6 and SR-9 (p<0.05); however, there was no significant difference in the average axial force between SR-6 and SR-9 (p>0.05). The average axial force of SR-6 was positive, which meant that the axial force of the soil on 3 spiral horizontal blades was greater than that on 6 rotary blades. The average axial forces of SR-8-1 and SR-9 were negative, which meant that the axial force of the soil on 3 spiral horizontal blades was less than that on 7 (9) rotary blades. Obviously, the absolute value of the average axial force on SR-8-1 was the smallest, which was 65.72% and 80.39% lower than those of SR-6 and SR-9, respectively. This showed that the configuration of rotary blades designed by theoretical calculation was more reasonable. The range of axial force applied to SR-8-1 (maximum axial force minus minimum axial force) was 339.24 N, which was 18.79% and 1.10% lower than those of SR-6 (417.73 N) and SR-9 (343.00 N), respectively. In conclusion, SR-8-1 has lower average axial force and axial force ranges than SR-6 and SR-9, which had a positive effect on improving the stability of the machine and balancing the axial soil throwing amount of RBBR.

Field test

The comparison of various test indicators after tillage by field test and simulation is shown in Table 2. The results of field verification test and simulation are similar. The BET, HSR-N and STD of SR-8-1 were better than those of SR-6, which proved that the results of the simulation were reliable. Compared with SR-6, the power of SR-8-1, in field verification test and simulation, increased by 5.16% and 12.06%, respectively. This was mainly because SR-8-1 was equipped with more rotary blades in the width range than SR-6, so the power increased accordingly.

When the working condition is sandy loam, there is less bulging at the bottom after tillage by SR-6. In this case, the BET of SR-6 will be reduced, and HSR-N and STD will be increased accordingly. To reduce the power of the tractor, SR-6 can be selected as the tillage tool. However, when the soil conditions are poor, SR-8-1 should be selected as often as possible to improve the soil tillage quality.

Conclusions

To achieve the optimal structure of RBBR, this study optimized the configuration of rotary blades on RBBR. Additionally, the tillage performance of different RBBRs was evaluated using DEM. The results showed that SR-8-1 obtain a flatter bottom, with a BET of 6.35 mm, which was 40.49% and 40.65% lower than SR-6 (10.67 mm) and SR-9 (10.70 mm), respectively. SR-8-1 was better than SR-6 and SR-9 in achieving the predetermined tillage depth, with a minimum average deviation of 6.06%. The average STD of SR-8-1 under the three theoretical tillage depths was 95.35%, which was 5.12% and 3.84% higher than those of SR-6 (90.71%) and SR-9 (91.69%), respectively. The absolute value of the average axial force on SR-8-1 (5.54 N) was the smallest, which was 65.72% and 80.39% lower than those of SR-6 (16.16 N) and SR-9 (28.25 N), respectively.

In field validation test and simulation, the power of SR-8-1 increased by 5.16% and 12.06% respectively compared to SR-6. However, SR-8-1 outperforms SR-6 in other tillage performance. Therefore, it is recommended to prioritizing SR-6 for tillage in sandy loam soil and SR-8-1 for clay loam soil.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province [grant number ZR2022QE150], the Shandong Provincial Science and Technology-based Small and Medium Enterprises Innovation Capacity Improvement Project [grant number 2024TSGC0271], the Shandong Province Agricultural Machinery R&D, Manufacturing, Promotion and Application Integration Pilot Project [grant number NJYTHSD-202315].

References

-

Aikins, K. A., Barr, J. B., Antille, D. L., Ucgul, M., Jensen, T. A., & Desbiolles, J. M. A. (2021). Analysis of effect of bentleg opener geometry on performance in cohesive soil using the discrete element method. Biosystems Engineering, 209, 106 - 124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2021.06.007

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2021.06.007 -

Asl, J. H., Singh, S. (2009). Optimization and evaluation of rotary tiller blades: computer solution of mathematical relations. Soil & Tillage Research, 106, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2009.09.011

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2009.09.011 -

Awuah, E., Zhou, J., Liang, Z., Aikins, K. A., Gbenontin, B. V., Mecha, P., & Makange, N. R. (2022). Parametric analysis and numerical optimisation of Jerusalem artichoke vibrating digging shovel using discrete element method. Soil & Tillage Research, 219, 105344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2022.105344

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2022.105344 - Chinese Standard Committee. (2017). GB/T 5668-2017. Rotary Tiller, Chinese Standard Press.

-

Du, J., Heng, Y., Zheng, K., Luo, C., Zhu, Y., Zhang, J., & Xia, J. (2022). Investigation of the burial and mixing performance of a rotary tiller using discrete element method. Soil & Tillage Research, 220, 105349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2022.105349

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2022.105349 -

Fang, H., Ji, C., Zhang, Q., Guo, J. (2016). Force analysis of rotary blade based on distinct element method. Transactions of the CSAE, 32(21), 54-59. https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2016.21.007

» https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2016.21.007 -

Feng, X., Liu, T., Wang, L., Yu, Y., Zhang, S., & Song, L. (2021). Investigation on JKR surface energy of high-humidity maize grains. Powder Technology, 382, 406-419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2020.12.051

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2020.12.051 -

Islam, M. U., Jiang, F., Guo, Z., Liu, S., & Peng, X. (2023). Impacts of straw return coupled with tillage practices on soil organic carbon stock in upland wheat and maize croplands in China: A meta-analysis. Soil & Tillage Research, 232, 105786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2023.105786

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2023.105786 -

Ji, W., Jia, H., Tong, J. (2012). Experiment on working performance of bionic blade for soil-rototilling and stubble-breaking. Transactions of the CSAE, 28(12), 24-30. http://www.tcsae.org/article/id/20121205

» http://www.tcsae.org/article/id/20121205 -

Kataoka, T., Shibusawa, S. (2002). Soil-blade dynamics in reverse-rotational rotary tillage. Journal of Terramechanics, 39(2), 95 - 113. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4898(02)00004-6

» https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4898 -

Khan, H., Khan, A., Khan, S., Anjum, A., Akbar, H., & Muhammad, D. (2024). Maize productivity and nutrient status in response to crop residue mineralization with beneficial microbes under various tillage practices. Soil & Tillage Research, 239, 106057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2024.106057

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2024.106057 -

Kim, Y. S., Siddique, M. A. A., Kim, W. S., Kim, Y. J., Lee, S. D., Lee, D. K., Hwang, S. J., Nam, J. S., Park, S. U., & Lim, R. G. (2021). DEM simulation for draft force prediction of moldboard plow according to the tillage depth in cohesive soil. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 189, 106368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106368

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106368 -

Li, B., Chen, Y., Chen, J. (2016). Modeling of soil-claw interaction using the discrete element method (DEM). Soil & Tillage Research, 158, 177-185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2015.12.010

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2015.12.010 -

Mairghany, M., Yahya, A., Adam, N. M., Mat, A.S., Su, A. W., & Elsoragaby, S. (2019). Rotary tillage effects on some selected physical properties of fine textured soil in wetland rice cultivation in Malaysia. Soil & Tillage Research, 194, 104318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2019.104318

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2019.104318 -

Makange, N. R., Ji, C. Y., & Torotwa, I. (2020). Prediction of cutting forces and soil behavior with discrete element simulation. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 179, 105848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105848

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105848 -

Matin, M. A., Desbiolles, J. M. A., Fielke, J. M. A. (2016). Strip-tillage by rotating straight blades: effect of cutting-edge geometry on furrow parameters. Soil & Tillage Research, 155, 271-279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2015.08.016

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2015.08.016 -

Matin, M. A., Fielke, J. M., Desbiolles, J. M. A. (2014). Furrow parameters in rotary strip-tillage: Effect of blade geometry and rotary speed. Biosystems Engineering, 118, 7-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2013.10.015

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2013.10.015 -

Salokhe, V. M., Ramalingam, N. (2002). Effect of rotation direction of a rotary tiller on draft and power requirements in a Bangkok clay soil. Journal of Terramechanics, 39(4), 195-205. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4898(03)00013-2

» https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4898 -

Song, W., Jiang, X., Li, L., Ren, L., & Tong, J. (2022). Increasing the width of disturbance of plough pan with bionic inspired subsoilers. Soil & Tillage Research, 220, 105356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2022.105356

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2022.105356 -

Wang, X., Gao, P., Yue, B., Shen, H., Fu, Z., Zheng, Z., Zhu, R., & Huang, Y. (2019). Optimisation of installation parameters of subsoiler' wing using the discrete element method. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 162, 523 - 530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2019.04.044

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2019.04.044 -

Wang, Y., Zhang, D., Yang, L., Cui, T., Jing, H., & Zhong, X. (2020). Modeling the interaction of soil and a vibrating subsoiler using the discrete element method. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 174, 105518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105518

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105518 -

Xiong, P., Yang, Z., Sun, Z., Zhang, Q., Huang, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2018). Simulation analysis and experiment for three-axis working resistances of rotary blade based on discrete element method. Transactions of the CSAE, 34(18), 113 - 121. https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2018.18.014

» https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2018.18.014 -

Zeng, Z., Ma, X., Chen, Y., & Qi, L. (2020). Modelling residue incorporation of selected chisel ploughing tools using the discrete element method (DEM). Soil & Tillage Research, 197, 104505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2019.104505

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2019.104505 -

Zhang, L., Zhai, Y., Chen, J., Zhang, Z., & Huang, S. (2022). Optimization design and performance study of a subsoiler underlying the tea garden subsoiling mechanism based on bionics and EDEM. Soil & Tillage Research, 220, 105375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2022.105375

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2022.105375 -

Zhang, X., Zhang, J., Xia, J., Zhang, S., Zhai, J., & Wu, H. (2015). Design and experiment on critical component of cultivator for straw returning in paddy field and dry land. Transactions of the CSAE, 31(11), 10-16. https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2015.11.002

» https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2015.11.002 -

Zhou, H., Li, D., Liu, Z., Li, Z., Luo, S., & Xia, J. (2019a). Simulation and experiment of spatial distribution effect after straw incorporation into soil by rotary burial. Transactions of the CSAM, 50(9), 69-77. https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2019.09.008

» https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2019.09.008 - Zhou, H., Zhang, C., Zhang, J., Xia, J. (2020). Discrete element simulation and operation parameter optimization of slide-cutting subsoiler based on clay loam. International Agricultural Engineering Journal, 29(4), 64-74.

-

Zhou, H., Zhang, J., Xia, J., Tahir, H. M., Zhu, Y., & Zhang, C. (2019b). Effects of subsoiling on working quality and total power consumption for high stubble straw returning machine. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering, 12(4), 56-62. https://doi.org/10.25165/j.ijabe.20191204.4608

» https://doi.org/10.25165/j.ijabe.20191204.4608 -

Zhu, Y., Xia, J., Zeng, R., Zheng, K., Du, J., Liu, Z. (2020). Prediction model of rotary tillage power consumption in paddy stubble field based on discrete element method. Transactions of the CSAM, 51(10), 42-50. https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2020.10.006

» https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2020.10.006

Edited by

-

Area Editor:

Tiago Rodrigo Francetto

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

02 June 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

04 Sept 2024 -

Accepted

09 Apr 2025

Study the tillage performance of different rotary burying blade rollers based on discrete element method

Study the tillage performance of different rotary burying blade rollers based on discrete element method