ABSTRACT

The potential of oilseed radish at two sowing dates for use as a raw material in biogas (biomethane) production based on laboratory anaerobic digestion with the addition of inoculum with a 60-day incubation period was investigated. The results of biogas productivity were compared with traditional cruciferous species used for bioenergy purposes. In the spring-sown variants, the achievable level of ground bioproductivity of oilseed radish was set at 25.17 t ha−1 of raw and 3.20 t ha−1 of dry matter, which provided a biomethane yield (SMY) of 320.07 ± 31.39 LN kg−1ODM and an indicator of methane accumulation intensity (Rm(ef)) of 130.76 ± 10.20 LN kg−1ODM d−1 with an appropriate biochemical portfolio of the formed biomass. During the summer sowing period, the average bioproductivity of oilseed radish was 18.42 t ha−1 in raw weight and 2.81 t ha−1 in dry matter, which provided an SMY of 262.97 ± 24.64 LN kg−1ODM and an Rm(ef) of 122.22 ± 3.62 LN kg−1ODM d−1 with its appropriate biochemical composition. The maximum level of biomethane production from oilseed radish was achieved with spring sowing under the conditions of 2021, resulting in the following technological parameters of productivity: MS 55.84 ± 9.39%, SMY 359.25 ± 11.24 LN kg−1ODM, Rm(ef) 138.15 ± 1.78 LN kg−1ODM d−1, Rm(full) 31.51 ± 1.69 LN kg−1ODM d−1, t50 4.12 ± 0.34 days, and λ 1.74 ± 0.17 days.

cover crops; biomass; anaerobic fermentation; biogas; specific methane yield

INTRODUCTION

The growing demand for fossil energy resources has resulted in intensified environmental pollution and soil degradation. The dynamics of such processes have become a threat to the preservation of highly productive agricultural landscapes in many countries (Waithaka, 2023). One way to reduce these negative processes is the development of green energy technologies aimed at producing biofuels and biogas (Kaletnik et al., 2020) with the formation of an energy supply for rural areas (Tokarchuk et al., 2020; Honcharuk et al., 2023 a, b) and derivative components for bioorganic fertiliser technologies (Lohosha et al., 2023; Nichols & MacKenzie, 2023). In this regard, it is important to identify plant resources with high technological adaptive potential, a wide distribution and cost-effective biogas production for use in anaerobic fermentation technologies (Herrmann et al., 2016). Cruciferous plant species have been identified as effective biogas resources with high potential (Molinuevo-Salces et al., 2015; Chapagain et al., 2020; Oliveira & Słomka, 2021; Shitophyta et al., 2023). However, most estimates refer to traditional mustard and rapeseed crops (rapeseed, mustard). The use of oilseed radish has mainly been related to the use of its derivative green manure (intermediate) after preliminary silage fermentation (Molinuevo-Salces et al., 2015; Herrmann et al., 2016). This significantly narrows the technological options for its use given the established agro-technological potential (Tsytsiura, 2023, 2024, 2024 a, b). This is especially true for options for formed biomass use, with the expansion of the range of agrobiomass use in the main and intermediate terms of cultivation. In addition, the dynamic long-term biochemical portfolio, which determines the quality of the generated biomass, is poorly understood for crops, especially in terms of their impact on the chemistry, dynamics and productivity of the biogas anaerobic fermentation process. These factors are the result of crop selection for regional biogas production.

Such approaches enable the assessment of the biogas potential of oilseed radish in a new way and expand the variability of biogas fermentation technologies using its biomass. Given the outlined novelty, this was the aim of our study.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

General conditions. The oilseed radish biomass used in the study was grown from 2020 to 2023 in the experimental field of Vinnytsia National Agrarian University (N 49°11’31”, E 28°22’16”.). The soil cover of the field was Greyi-Luvic Phaeozems (Phaeozems Albic, Dark Gray Podzolic Soil) of silty clay with a loamy texture. The agrochemical potential of the soil (0–30 cm) was as follows: humus content, 2.68%; hydrolysed nitrogen, 81.5 mg kg−1; mobile phosphorus (P), 176.1 mg kg−1; exchangeable potassium (K), 110.8 mg kg−1; рНкcl 5.8. The variety of combined uses of ‘Zhuravka’ has grown. There was an unfertilised background with a seeding rate of 2.5 million seeds ha−1 with a row spacing of 15 cm. Two growing dates were evaluated: early spring sowing (the first or second week of April) and summer sowing (the second or third week of July). The experiment was designed in four replicates of each treatment using the method of small-plot randomisation (total plot area 35 m2, accounting plot area 25 m2). Aboveground plant biomass was collected at the flowering stage (BBCH 64–67) in 4 randomised plots of 1 m2 in each replication.

Chemical analysis of the biomass. Chemical analysis of the biomass was carried out in quadruplicate with the crushed sample mass expressed on an absolutely dry weight basis. The dry matter (DM) and organic dry matter (ODM) contents were measured by drying the biomass in an oven at 105°C and then ashing the dried sample at 550°C. The ash content (AOAC Official Method 942.05) was determined as the gravimetric loss by heating to 600°C for 2 h. Crude fibre (CFb) (AOAC Official Method 978.10) was determined gravimetrically as the residue remaining after acid and alkaline digestion. The сrude fat content (CF) (AOAC Official Method 2003.05) was determined using the Randall modification of the standard Soxhlet extraction. The total nitrogen content (TNC) was determined using the Kjeldahl method (AOAC Official Method 978.04) with the dry biomass and a KjeLROC Kd-310 analyser (OPSIS LiquidLINE, Sweden) (ISO 17025). The total crude protein (СР) content was calculated as the nitrogen content multiplied by the standard conversion factor of 6.25 (AOAC Official Method 990.03 and AOAC Official Method 978.04). The total organic carbon (TOC) content was determined using a laboratory analyser (TOC-LCPH series) according to the standard protocol for low-temperature thermocatalytic oxidation of plant material. The neutral detergent fibre (NDF) content was determined using the AOAC Official Method 2002-04 with neutral detergent solution and heat. Sodium sulphite was used to remove nitrogenous matter. Heat-stable amylase was remove starch and inactivate potential contaminating enzymes that might degrade fibrous constituents. The acid detergent fibre (ADF) content was determined gravimetrically as the residue remaining after acid detergent extraction (AOAC Official Method 973.18). Analysis of the tissue for acid detergent lignin (ADL) followed the ADF-Sulphuric Lignin method (AOAC Official Method 973.18). The cellulose content was determined as the difference between ADF and ADL, and the hemicellulose content was determined as the difference between NDF and ADF in accordance with the Van Soest method. The carbohydrate content was determined by the sum of nitrogen-free extracts (NfE) and crude fibre (CFb). The carbon/nitrogen (C/N) ratio was calculated as the ratio of TOC to TNC. Nitrogen-free extracts (NfE) were calculated as the difference between the content of 100% DM and the corresponding content of CP, CFb, CF and CA. The residue quality (RQ) was calculated as the sum of its labile (100-NDF) and cellulose (ADF-L) decomposable fractions. The glucosinolate (GSL) content was determined in frozen plants using high performance liquid chromatography according to standard methods (ISO 9167:2019). The contents of total P and K in plants was determined according to Method of Measurement 31-497058-019-200531-497058-019-2005. The calcium (Ca) content was determined using the complexometric method (AOAC Official Method 935.13). The sulphur (S) content was determined in accordance with AOAC 923.01-1923.

Anaerobic fermentation technology. For anaerobic biogas fermentation, 1-L glass vessels were used. As a substrate, we used a mass of crushed oilseed radish plants to simulate mechanical harvesting. Digestive enzyme ‘Efluent’ certified in 2018 (Lohosha et al., 2023) was used as inoculum and had the following chemical characteristics: pH 8.2 ± 0.3; DM, 2.5 ± 0.7%; Total dissolved solids (TDS), 62.7 ± 3.3% of DM; N, 2.9 ± 1.2 g kg−1; NH4–N, 2.3 ± 0.7 g kg−1; organic acids, 1.7 ± 0.5 g kg−1; TOC, 32.8 ± 2.7 %DM; TNC, 1.64 ± 0.39 %DM; and C/N ratio, 20 ± 2.5). The substrate-to-inoculum ratio (S/I ratio of ODMsubstrate to ODMinoculum) was maintained at 5 (based on the DM content) in all years with the selection of inoculum and substrate mass for each variant (on the ODM content) and a stable conversion factor of biogas productivity from mL to LN kg−1ODM = 5−1). The final volume of the vessel was normalised to a pH of 7.0–7.2 using 10M NaOH solution. The bottles were purged with N2:CO2 gas (80:20, by volume) to create an anaerobic environment. A reactor containing only inoculum was considered the control variant. The vessels were placed in a water bath (constant temperature of 35°C ± 0.5) with an incubation period of 60 days and active shaking once a day at the same time. The biogas generated during the incubation period was collected in wet gas metres and recorded daily (normalised to standard conditions (dry gas, 0°C, 1013 hPa)) using a standard procedure for the displacement of acidified saturated barrier solution with NaCl. The biogas composition was measured using a portable gas analyser equipped with infrared sensors (Mobile Biogas analyser H2S, CH4, CO2, O2, Multi Instruments Analytical, Netherlands). The specific methane yield (SMY, LN kg−1ODM) was determined by dividing the gas volume by the mass of the substrate (in ODM).

Kinetics of biogas productivity. Three models were used to determine the kinetics of biogas productivity. The ‘First-order’ model was calculated as follows (Equation 1):

Where:

y(t) is the cumulative specific methane yield at time t (LN kg−1ODM);

ym is the maximum specific methane yield at a theoretically infinite digestion time (LN kg−1ODM);

t is the time (days); and k1 is the first order decay constant (day−1), e =2.7183.

The ‘Fitzhugh’ model was calculated as follows (Equation 2):

Where:

n is a dimensionless shape factor.

The ‘Modified Gompertz’ model was calculated as follows (Equation 3):

Where:

Rm is the maximum specific methane production rate (LN kg−1ODM d−1), and

λ is the lag phase (d).

The specific methane production rate (Rm) was determined using [eq. (4)]:

These models were analysed for significant deviations from the actual kinetics graphs using the CurveExpert Professional v. 2.7.3 software package (Hyams Development). The lag period (λ) was defined as converted to a day length of 24 h. The half-life (t50, days) was determined as the time when 50% of the SMY was reached.

The indicators of statistical variation were determined in Statistica 10 (StatSoft – Dell Software Company, USA), Past 4.13 (Øyvind Hammer, Norway) and R (R statistic i386 3.5.3). For each analysed parameter, the used standard deviation (SD), coefficient of variation (CV), Pearson’s correlation coefficient, analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the least significant difference (p<0.05; (LSD05)) and Tukey HSD test were used at a statistical level of р < 0.05. To compare the fit of regression models, we used the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE) and relative root mean square error (RRMSE). The degree of connection was estimated using the coefficient of determination (Equation 5):

Where:

rij is the correlation coefficient between the i-th and j-th indicators.

Weather conditions. The hydrothermal regime of the oilseed radish vegetation period over the years of study (Figure 1) showed significant differences within the interannual comparison. Considering the optimal parameters for the formation of oilseed radish leaf–stem mass (average daily temperature 14–16°C with precipitation of 220–240 mm (Tsytsiura, 2020)), the years of research were placed in the following order of increasing favourability for spring sowing: 2021 > 2022 > 2023 > 2020. For summer sowing, the order was as follows: 2021 > 2023 > 2020 > 2022.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Оilseed radish demonstrated significant bioenergy resource potential (Table 1). The total productivity of the formed aboveground biomass was 25.17 t ha−1 (3.20 t ha−1 in DM) in the spring and 18.42 t ha−1 (2.81 t ha−1) in the summer sowing period. The ratio for the productivity of summer and spring sowing was 73.2%, indicating a sensitive response and a significant impact of the hydrothermal conditions of the growing season. The interannual variation for the spring sowing period in terms of the amount of aboveground biomass formed was 16.24% and for a dry mass yield of 17.28%.

The same figures for the summer sowing date were 32.09 and 25.73%. According to Quintarelli et al. (2022) and Yang et al. (2023), oilseed radish should be classified as a highly productive crop effective in providing options for intermediate use in summer–autumn crop rotations.

The biochemical portfolio of the leaf–stem mass was evaluated at the flowering stage (BBCH 64–67) on different sowing dates (Tables 2 and 3). The flowering phase (for most cruciferous crops, BBCH 55–74) was the most adapted in its technological use for different areas of agrotechnological application (cover crop–fodder (silage)–sideration–biogas production) (Quintarelli et al., 2022).

Differences in the biochemical composition of oil radish leaf mass at different sowing dates were found. With the general classification of biomass as high protein (the average CP content for the dataset for 2 sowing dates was above 17 %DM) with a high content of crude fat (CF) (4.04 %DM) and crude ash (CA) (14.22 %DM), the shift in sowing dates from spring to summer significantly changed the biochemical composition of the leaf mass (Tables 2 and 3). An increase in the CP content (with a comparable growth index of 1.44), crude fat content (1.20), CA content (1.21) and crude fibre (1.10) was noted. At the same time, changes in cellulose-derived components, basic ash elements, and glucosinolate composition (the latter component is characteristic of the plant mass of cruciferous species (Ţiţei, 2022)) were demonstrated. The coefficients of the spring sowing/summer sowing ratio (according to the average annual values in Tables 2 and 3) were 1.03–1.11 for ОDM, 0.63–0.70 for ADL, 0.78–0.85 for cellulose, 0.71–0.85 for hemicellulose, 0.72–0.84 for TNC, 0.87–0.96 for TOC, 0.84–0.97 for P, 0.82–0.90 for K, 0.81–0.93 for Ca, 0.73–0.88 for S and 0.78–0.87 for GSL.

This type of formation of indicators for changes in sowing dates is explained by the significant influence of hydrothermal conditions of the growing season determined during the study period, considering their average annual values. The general biochemical model of the aboveground oilseed radish biomass, considering the basic criterion evaluation of plant biomass for biogas production (Herrmann et al., 2016; Meegoda et al., 2018; Ošlaj et al., 2019; Fajobi et al., 2023) in the spring sowing season, was appropriate for biogas production. In the summer sowing season, the feasibility of using oilseed radish biomass shifted towards green manure and as a cover crop. This was confirmed by а high ash content in the aboveground biomass (more than 12%DM) against the background of a high P, K, Ca and S content (according to Quintarelli et al., 2022), demonstrating the possibility of using aboveground oilseed radish biomass for nutrient recycling through its return to the soil with green fertilisers.

Regarding the comparison of the biochemical profile of oilseed radish with other cruciferous crops (such as white mustard, spring and winter rape, and typhon), previous studies have shown a reduction in CP by 3.4–8.7 %DM, ADL content by 0.7–2.5%DM, CFb content by 1.9–6.1%DM, P content by 0.12–0.22%DM, S content by 0.27–0.35%DM, and glucosinolate content by 13–20 μmol g−1DM (compared to other crucifers; 11–56 μmol g−1DM for white mustard, 9–51 μmol g−1DM for spring and winter rape), an increase in CF content by 1.3–2.4%DM, CA content by 1.7–2.2%DM, and K content by 1.8–3.7%DM, and a similar Ca content (Blažević et al., 2020; Ţiţei, 2022; Oliveira & Słomka, 2021; Shitophyta et al., 2023)).

Yang et al. (2023) found that the biochemical assessment of plant mass should include a system of appropriate ratios that determine the processes of decomposition, mineralisation and the predicted intensity of anaerobic digestion. These ratios for oilseed radish are presented in Table 4. Manyi-Loh & Lues (2023) established that the optimal C/N ratio for the anaerobic digestion of biomass was in the range of 20–30 with an interval of possible deviations in the range of 10–30. Low C/N ratios significantly increase the concentration of the ammonium form and the rapid microbial process of anaerobic digestion. Thus, we should expect a relatively rapid decomposition of oilseed radish plant mass during digestion with a short lag period.

The C/P ratio indicated the possible inhibition of biomass decomposition during biofermentation with an increase in the concentrations of P and its derivatives as well as a possible decrease in methane production with an increase in the dissolved orthophosphate concentration in the digestate above 250 mg L−1 (Xi et al., 2023). Therefore, an increased P content in digestate with oilseed radish plant mass should be expected and influenced by the dynamics of the ‘half-life’ (t50) and ‘lag period’ (λ).

The C/S ratio is a relative indicator of the presence of glucosinolates in plant biomass (Blažević et al., 2020). A significantly higher value of this indicator in the spring-sown aboveground biomass indicates a higher proportion of the generative part, a higher reproductive effort of the oilseed radish plants (Tsytsiura, 2022). The effect of glucosinolates on the biomethane productivity of plant biomass is debatable. However, according to previous studies (Blažević et al., 2020; Sun, 2020), glucosinolates can act as an inhibitor of the dynamics and volume of biomethane production. Cleemput (2011) found no direct formative effect of the glucosinolate content on the biomethane yield and concentration, and the resulting effect was determined by technological factors (sugar content, pH, and NfE and carbohydrate contents). However, the carbohydrate content determines the dynamics of mass decomposition in terms of released substances. Most crops with a high biogas production potential have a carbohydrate content of 65–75%DM (Venslauskas et al., 2024). Similarly, a NfE content for successful anaerobic fermentation was observed in the range of 40–55%DM (Meegoda et al., 2018), and for effective methane anaerobic fermentation, the residue quality (RQ) should be at least 80%DM (Pokój et al., 2020). Based on these statements, the oilseed radish biomass formed by the plant during the spring sowing period with an average carbonate content of 67.08%DM and average NfE content of 47.03%DM was technologically more suitable for biogas production than that from the summer sowing period.

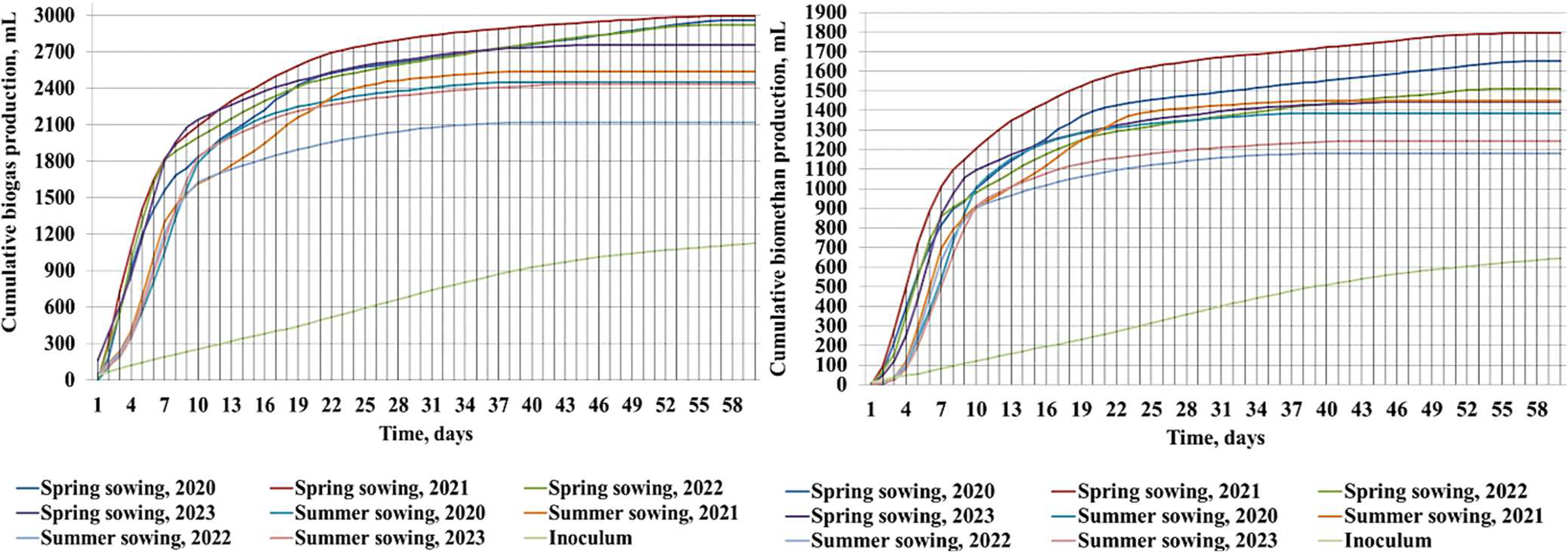

The biochemical quality of oilseed radish leaf–stem mass was confirmed by the laboratory assessment of the biogas and methanogenic potential (Figure 2).

Cumulative biogas (left position) and biomethane production (right position) during the experimental period obtained from oilseed radish plant mass (inoculum subtracted) from different sowing dates, mL (average adjusted for biomethane productivity of inoculum and standardised dry gas indicators), 2020–2023 (the conversion factor of biogas productivity from mL in LN kg−1ODM = 5−1)

The maximum achievable technological level of cumulative biogas accumulation ranged from 2117 to 2997 mL (423–600 LN kg−1ODM) for 60 days. The average value was 2908 mL (581.6 LN kg−1ODM) for the spring sowing period and 2384 mL (476.8 LN kg−1ODM) for the summer, i.e. 22% less. The interannual variation for the summer sowing date was 7.71%, which was almost twice as high as the average for the spring sowing date. The cumulative biomethane yield was 1179–1796 mL (235.8–359.2 LN kg−1ODM). The average biomethane productivity was 1600 mL (320 LN kg−1ODM) for spring sowing and 1314 mL (262.8 LN kg−1ODM) for summer sowing. For other cruciferous crops (white mustard and spring and winter rape), the interval for cumulative biogas accumulation had wide limits of 1480–4500 mL, and the cumulative biomethane yield was 800–2400 mL (Molinuevo-Salces et al., 2015; Herrmann et al., 2016; Oliveira & Słomka, 2021; Shitophyta et al., 2023; Słomka & Pawłowska, 2024). Considering this, oilseed radish mass was not inferior in efficiency to that of widely used cruciferous crops.

The analysis of the dynamics of biogas production in the context of the daily accounting period for the different variants studied is presented in Figure 3. These dynamics can be assessed as oscillatory, with a steady increase in the indicator up to 2–8 days of fermentation and its steady decline up to 37–58 days, depending on the variant. This characteristic was noted for the total biogas and biomethane productivity.

Total biogas and biomethane productivity of anaerobic digestion of oilseed radish biomass from different sowing dates adjusted for the biogas productivity of inoculum obtained in the control variant and the dynamics of biomethane concentration (CH4, %) (over the 55-day incubation period), 2020–2023 (the conversion factor of biogas productivity from mL to LN kg−1ODM = 5−1).

Despite the similarity of the curves, specific differences were observed. For the spring sowing dates, a short lag period (λ) with fluctuations of 1.58–1.85 days with a peak value of indicators at 5–7 days, an average fermentation duration of 53.5 days and an average half-life (t50) of 4.69 days was established. Three periods were identified in the graphs for spring sowing, which were conditionally called ‘growth’ (period 2–8 days of anaerobic digestion), ‘decline’ (9–22 days) and ‘stagnation’ (22–58 days). For the summer sowing dates, an increase in the lag period was noted for the variants to 2.09 days, with a peak value of biogas productivity at 6–10 days, an average fermentation duration of 38.7 days and an average t50 of 5.94 days. The schedule was divided into the following phases: ‘growth’ (3–10 days of anaerobic digestion), ‘decline’ (11–25 days), and ‘stagnation’ (26–43 days), similar to the spring sowing period. In general, the overall assessment of the dynamics of biogas yield from oilseed radish plant mass was assessed as relatively predictable with a rapid course of the process and the duration of the effective increase in biogas and biomethane accumulation up to 20–25 days of anaerobic digestion. The inoculum with methane production up to 20–30 days was positively correlated with the requirements for anaerobic digestion, according to Uddin & Wright (2023). The presented dynamics share of biomethane (CH4, %) (Figure 3) corresponded to the nature of cumulative biomethane accumulation and had a dynamic curve with a peak value at 5–10 days and a steady decrease from 11 to 34 days with a Cv of 3.78%.

Differences in the biomethane concentration were observed considering the sowing date (p < 0.05–0.001). The concentration was 54.47% (with interannual variation of Cv = 1.96%) for the spring-sown biomass and 53.74% (Cv = 3.10%) for the summer-sown biomass. The dynamic variation ing CH4 concentration during the period of anaerobic digestion was Cv = 13.22–16.82% for spring sowing and Cv = 12.14–17.74% for summer sowing depending on the year. According to the results of long-term assessments (Herrmann et al., 2016; Oliveira & Słomka, 2021), the CH4 concentration ranged from 44.7 to 72.7% for cruciferous species biomass (57.3–62.8% for winter rape, 57.6–59.5% for turnip, 51.5–60.8% for different types of mustard).

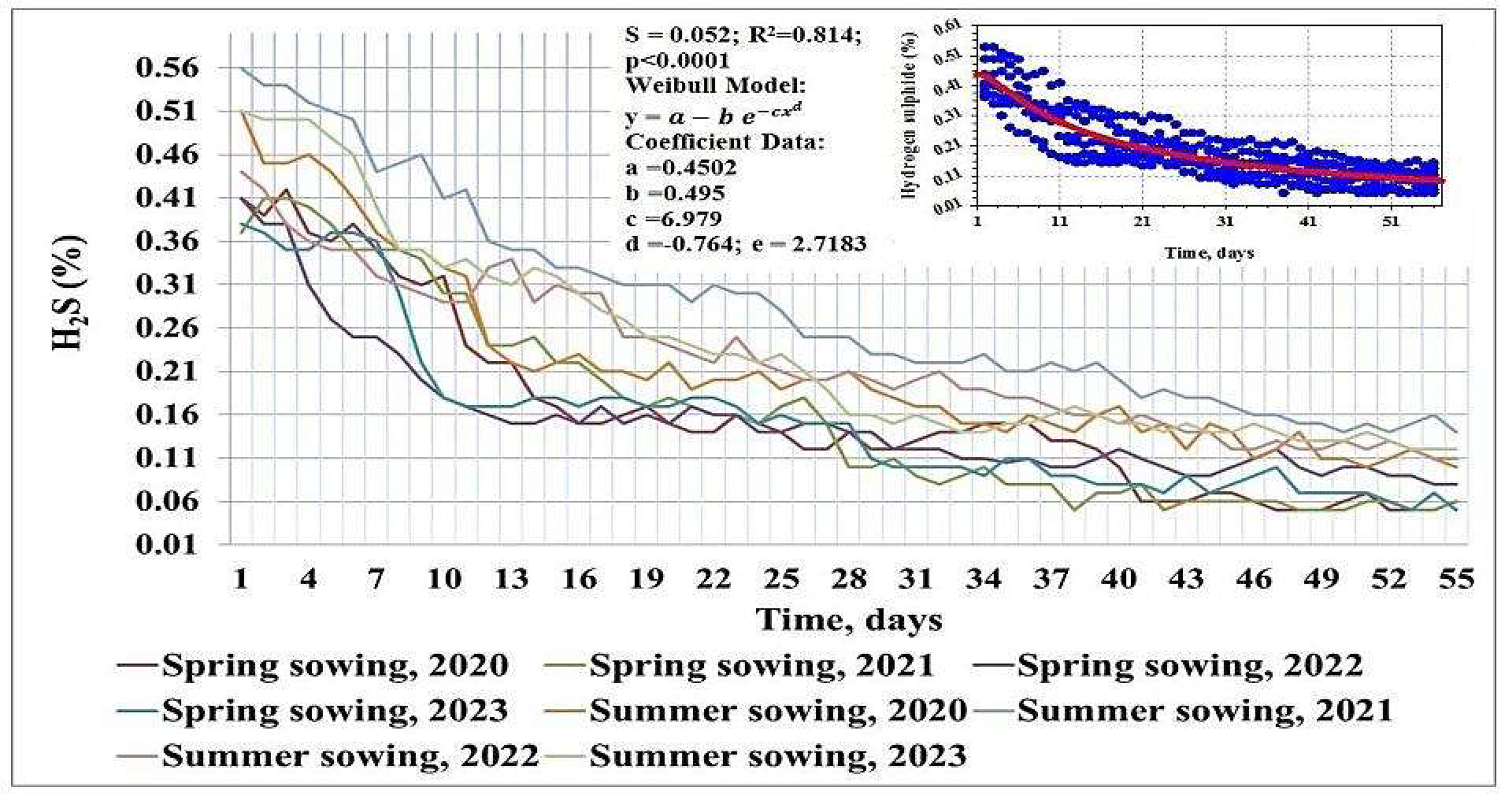

The high S content in the oilseed radish plant mass at both sowing dates, in accordance with the requirements for controlled conditions of anaerobic digestion (Fajobi et al., 2023), necessitated the assessment of the hydrogen sulphide concentration in the total volume of biogas produced. The results of such monitoring are shown in Figure 4. The average hydrogen sulphide concentration over the 55-day incubation was 0.15% (interannual coefficient of variation Cv = 64.86%) for the spring sowing variant and 0.23% (47.86%) for the summer sowing variant.

Share of hydrogen sulphide (H2S) in the biogas volume obtained from anaerobic digestion (over the 55-day incubation period) of oilseed radish biomass from different sowing dates in inoculum-based co-digestion mixtures, 2020–2023.

The highest hydrogen sulphide content in the total volume of biogas produced was noted on the first day of the incubation period in the range of 0.37–0.56%, with a subsequent steady decline. The dynamic process in the overall dataset was described by the ‘Weibull’ model: (with R2 = 0.814 at p<0.0001). The presence of a negative corresponds to the biogas daily productivity formation from the date of peak value achievement, which explains the increasing biomethane concentration and fluctuations in the indicator in the 5–10 days of anaerobic incubation. This positive dynamic confirmed both the high S content in the oilseed radish biomass and the intensive decomposition with a short lag period and corresponded to the established general patterns of anaerobic digestion of cruciferous crops. Shitophyta et al. (2023) found that cruciferous species, such as white and brown mustard, rapeseed, and fodder radish, were characterised by a hydrogen sulphide concentration of 0.15–0.90% in terms of mgS L−1d−1 (ppm). This concentration did not eliminate the anaerobic digestion process but contributed to a decrease in the intensity of the process.

The mathematical analysis of biomethane accumulation (Table 5) confirmed the general conclusions of Shitophyta et al. (2023) regarding the effective use of Gompertz equations in modelling the anaerobic digestion of oilseed radish mass. The maximum statistical accuracy of the model corresponded to the ‘Modified Gompertz’ type. This approach was demonstrated by the average increase in the approximation index (R2) of the model dependence of 1.92% when comparing the ‘First-order’ and ‘Modified Gompertz’ models as well as by the value of the coefficient k1 for both models. For different Brassicaceae, Oliveira & Słomka (2021) and Shitophyta et al. (2023) found that k1 was 0.065–0.273. Pabón-Pereira et al. (2020) noted that low k1 values indicated a low DM and high CP and NfE contents.

Our conclusions about the periodisation of anaerobic mass fermentation in daily terms (Figure 3) were confirmed by the resulting ‘Rational Function’ model of this process. This model indicated a variable descending character for this trait, with one or more peaks of different altitude dominance. The oilseed radish biomass was quite demanding for precise control of fermentation conditions and responded positively to the use of additional stabilising high-performance biocomponents.

The indicators of anaerobic digestion of the oilseed radish plant mass are presented in Table 6.

As for SMY, its level for different radish species and widely used cruciferous species had a wide range, 205–494 LN kg−1ODM, depending on plant variety, soil characteristics, climatic conditions, the portion of the plant digested and pretreatment methods (Raphanus sativus 274–474 LN kg−1ODM, Brassica napus 334–448 LN kg−1ODM, Brassica rapa 240–314 LN kg−1ODM, Brassica oleracea 310–373 LN kg−1ODM, Sinapis alba 239–440 LN kg−1ODM) (Lehtomäki, 2006; Molinuevo-Salces et al., 2015; Herrmann et al., 2016). The SMY for the spring sowing was, on average, 21.7% higher than for the summer sowing date (320.07 vs. 262.97 LN kg−1ODM). According to the same scientific literature for different types of cruciferous plant species, Rm had a more variable range of 96–403 LN kg−1ODM d−1.

It is also necessary to consider the calculation of this indicator, which can be divided into two types based on the anaerobic digestion of oilseed radish: for the entire period of anaerobic incubation (Rm(full)) and for the period of effective incremental gas accumulation (Rm(ef)). The value of the ratio Rm(ef)/Rm(ful) indicates the effective expediency of the anaerobic incubation duration (Meegoda et al., 2018).

Approaching 1, this ratio indicates the possibility of a long anaerobic fermentation process while maintaining relatively constant biogas yields. From this position, with the indicated average ratio of 0.22 for spring sowing and 0.30 for summer sowing, the plant biomass of oilseed radish was attributed to potential biogas feedstock with a medium-term anaerobic incubation period and co-fermentation with inoculum in the technological interval of 25–35 days.

The effect of the coefficient of determination on the SMY value is shown in Figure 5. Based on the results of this assessment, a number of parameters can be identified in the prediction of biomethane productivity under anaerobic digestion of the aboveground oilseed radish biomass.

Coefficients of determination (dxy) of the dependence of SMY and kinematic parameters of the anaerobic digestion process from biochemical parameters for oilseed radish leaf–stem mass, 2020–2023 (identification of dependence direct (+) and inverse (-)); *parameters showed in Tables 2, 3 and 5. Significance level of dxy: p < 0.05, 25.0–38.0%, p < 0.01 38.10–55.05%, p < 0.001 dxy > 55.05%).

These included the ADF and ADL contents with the highest level of detection above 70%, which was positively consistent with the crude fibre (CFb) content. The intensity of anaerobic digestion for the oilseed radish plant mass is determined to a large extent by the presence of lignified structures and fibre derivatives, which confirmed the positive relationship between SMY and Hcel and the inverse between SMY and Cel for summer sowing.

A multidirectional relationship with the P and K contents was observed given the significantly lower average SMY value during the summer sowing period. The influence of these elements was determined by stimulating the formation of cell structures, mechanical tissues and the total CA content of plant biomass. The influence of the S concentration on plant mass was inverse to the level of determination at −53.22% and to the glucosinolate concentration (−56.48%). Thus, varieties with lower contents of S and related glucosinolates should be selected for the anaerobic digestion of oilseed radish.

A generally negative relationship (no significant) with the C/N ratio was found. This confirmed that the chemistry of the process may be opposite at an equal C/N ratio. However, there was a positive significant relationship with other indicators, particularly carbohydrates. These results confirm the findings of Fajobi et al. (2023), who showed that the protein degradation efficiency was generally lower (28–79%) compared to that of carbohydrates (67–94%) and fats (86–91%). This forms the basis for the RQ of plant residues, as shown in the correlation analysis, which had a direct relationship with the SMY (p < 0.05). However, according to our results, there is a need to assess the CP/CF ratio, since the CP content had an inverse relationship with the crude fat (CF) content, which had a direct effect on SMY. According to Anacleto et al. (2024), this ratio is determined by the fat composition of the plant tissue. Awe et al. (2018) showed that biomethane productivity was promoted by the increased protein content and reduced fat content, confirming our results for the leaf–stem mass of oilseed radish from summer sowing with high CP and crude fat contents (Table 1). The parameters of the general kinematics of the anaerobic digestion process (MC, k1, Rm(ef), t50, λ) in relation to the value of SMY confirmed the analysis presented in previous studies for cruciferous species (Dandikas et al., 2018; Ošlaj et al., 2019; Rossi et al., 2022).

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the results of the dynamic-quantitative assessment of biogas productivity using the anaerobic digestion process, oilseed radish is classified as a cruciferous species with high potential for biomethane yields with cultivation as the main crop or as an intermediate crop in crop rotations. The use of spring-sown oilseed radish biomass had the following basic indicators of biomethane productivity: МС, 54.69 ± 1.19%; SMY, 320.07 ± 31.39 LN kg−1ODM; Rm(ef), 130.76 ± 10.20 LN kg−1ODM d−1; Rm(full), 28.93 ± 2.05 LN kg−1ODM d−1; t50, 4.69 ± 0.52 days; and λ, 1.75 ± 0.12 days. Similar parameters were observed for summer sowing as follows: МС, 53.74 ± 1.66%; SMY, 262.97 ± 24.64 LN kg−1ODM; Rm(ef), 122.22 ± 3.62 LN kg−1ODM d−1; Rm(full), 36.01 ± 5.24 LN kg−1ODM d−1; t50, 5.94 ± 0.56 days; and λ, 2.09 ± 0.44 days.

REFERENCES

-

Anacleto, T. M., Kozlowsky-Suzuki, B., Björn, A., Yekta, S. S., Masuda, L. S. M., de Oliveira, V. P., & Enrich-Prast, A. (2024). Methane yield response to pretreatment is dependent on substrate chemical composition: a meta-analysis on anaerobic digestion systems. Scientific Reports, 14, 1240. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51603-9

» https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51603-9 -

Awe, O. W., Lu, J., Wu, S., Zhao, Y., Nzihou, A., Lyczko, N., & Minh, D. P. (2018). Effect of Oilseed Content on Biogas Production, Process Performance and Stability of Food Waste Anaerobic Digestion. Waste and Biomass Valorization, 9(12), 2295-2306. https://doi.org/ff10.1007/s12649-017-0179-4ff

» https://doi.org/ff10.1007/s12649-017-0179-4ff -

Blaževic, I., Montaut, S., Burcul, F., Olsen, C.E., Burow, M., Rollin, P., & Agerbirk, N. (2020). Glucosinolate structural diversity, identification, chemical synthesis and metabolism in plants. Phytochemistry, 169, 112100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.112100

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.112100 -

Chapagain, T., Lee, E. A., & Raizada, M. N. (2020). The Potential of Multi-Species Mixtures to Diversify Cover Crop Benefits. Sustainability, 12(5), 2058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052058

» https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052058 -

Cleemput, S. (2011). Breeding for a reduced glucosinolate content in the green mass of rapeseed to improve its suitability for biogas production [PhD Thesis. Georg-August-Universität Göttingen]. https://doi.org/10.53846/goediss-1837

» https://doi.org/10.53846/goediss-1837 -

Dandikas, V., Heuwinkel, H., Lichti, F., Eckl, T., Drewes, J. E., & Koch, K. (2018). Correlation between hydrolysis rate constant and chemical composition of energy crops. Renewable Energy, 118, 34-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.10.019

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.10.019 -

Fajobi, M. O., Lasode, O. A., Adeleke, A. A., Ikubanni, P. P., & Balogun, A. O. (2023). Prediction of Biogas Yield from Codigestion of Lignocellulosic Biomass Using Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) Model. Journal of Engineering, 9335814. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/9335814

» https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/9335814 -

Herrmann, C., Idler, C., Heiermann, M. (2016). Biogas crops grown in energy crop rotations: Linking chemical composition and methane production characteristics. Bioresource Technology, 206, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.01.058

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.01.058 -

Honcharuk, I., Tokarchuk, D., Gontaruk, Y., Hreshchuk, H (2023a). Bioenergy recycling of household solid waste as a direction for ensuring sustainable development of rural areas. Polityka Energetyczna, 26(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.33223/epj/161467

» https://doi.org/10.33223/epj/161467 -

Honcharuk, I., Yemchyk, T., Tokarchuk, D., Bondarenko, V. (2023b). The Role of Bioenergy Utilization of Wastewater in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals for Ukraine. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 12(2), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.14207/ejsd.2023.v12n2p231

» https://doi.org/10.14207/ejsd.2023.v12n2p231 -

Kaletnik, H., Pryshliak, V., Pryshliak, N. (2020). Public Policy and Biofuels: Energy, Environment and Food Trilemma. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism, 104(36), 479–487. https://doi.org/10.14505/jemt.v10.3(35).01

» https://doi.org/10.14505/jemt.v10.3(35).01 -

Lehtomäki, A. (2006). Biogas Production from Energy Crops and Crop Residues. [Doctoral thesis, University of Jyväskylä, Finland]. https://jyx.jyu.fi/handle/123456789/13152

» https://jyx.jyu.fi/handle/123456789/13152 -

Lohosha, R., Palamarchuk, V., Krychkovskyi, V. (2023). Economic efficiency of using digestate from biogas plants in Ukraine when growing agricultural crops as a way of achieving the goals of the European Green Deal. Polityka Energetyczna, 26(2), 161–182. https://doi.org/10.33223/epj/163434

» https://doi.org/10.33223/epj/163434 -

Manyi-Loh, C. E., Lues, R. (2023). Anaerobic Digestion of Lignocellulosic Biomass: Substrate Characteristics (Challenge) and Innovation. Fermentation, 9(8), 755. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation9080755

» https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation9080755 -

Meegoda, J. N., Li, B., Patel, K., Wang, L. B. (2018). A review of the processes, parameters, and optimization of anaerobic digestion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15, 2224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102224

» https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102224 -

Molinuevo-Salces, B., Larsen, S. U., Ahring, B. K., Uellendahl, H. (2015). Biogas production from catch crops: increased yield by combined harvest of catch crops and straw and preservation by ensiling. Biomass Bioenergy, 79, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2015.04.040

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2015.04.040 -

Nichols, G. A., MacKenzie, C. A. (2023). Identifying research priorities through decision analysis: A case study for cover crops. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 7, 1040927. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1040927

» https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1040927 -

Oliveira, W. K., Słomka, A. (2021). Assessment of the Biogas Yield of White Mustard (Sinapis alba) Cultivated as Intercrops. Journal of Ecological Engineering, 22(7), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.12911/22998993/138815

» https://doi.org/10.12911/22998993/138815 -

Ošlaj, M., Šumenjak, T.K., Lakota, M., & Vindiš, P. (2019). Parametric and Nonparametric Approaches for Detecting the most Important Factors in Biogas Production. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies, 28(1), 291–301. https://doi.org/10.15244/pjoes/84768

» https://doi.org/10.15244/pjoes/84768 -

Pabón-Pereira, C. P., Hamelers, H.V.M., Matilla, I., & van Lier, J. B. (2020). New Insights on the Estimation of the Anaerobic Biodegradability of Plant Material: Identifying Valuable Plants for Sustainable Energy Production. Processes, 8(7), 806. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr8070806

» https://doi.org/10.3390/pr8070806 -

Pokój, T., Klimiuk, E., Bulkowska, K., & Ciesielski, S. (2020). Effect of Individual Components of Lignocellulosic Biomass on Methane Production and Methanogen Community Structure. Waste and Biomass Valorization, 11, 1421-1433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-018-0434-3

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-018-0434-3 -

Quintarelli, V., Radicetti, E., Allevato, E., Stazi, S.R., Haider, G., Abideen, Z., Bibi, S., Jamal, A., & Mancinelli, R. (2022). Cover Crops for Sustainable Cropping Systems: A Review. Agriculture, 12, 2076. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12122076

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12122076 -

Rossi, E., Pecorini, I., Iannelli, R. (2022). Multilinear regression model of biogas production prediction from dry anaerobic digestion of OFMSW. Sustainability, 14(4393), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084393

» https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084393 -

Shitophyta, L. M., Putri, S. R., Salsabiella, Z. A., Budiarti, G. I., Rauf, F., & Khan, A. (2023). Theoretical Biochemical Methane Potential Generated by the Anaerobic Digestion of Mustard Green Residues in Different Dilution Volumes. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies, 32(5), 4799-4804. https://doi.org/10.15244/pjoes/162690

» https://doi.org/10.15244/pjoes/162690 -

Sun, X. Z. (2020). Invited Review: Glucosinolates Might Result in Low Methane Emissions From Ruminants Fed Brassica Forages. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 588051. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.588051

» https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.588051 -

Słomka, A., Pawłowska, M. (2024). Catch and Cover Crops’ Use in the Energy Sector via Conversion into Biogas – Potential Benefits and Disadvantages. Energies, 17(3), 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17030600

» https://doi.org/10.3390/en17030600 -

Tokarchuk, D. M., & Pryshliak, N. V., Tokarchuk, O. A., & Mazur, K. V. (2020). Technical and economic aspects of biogas production at a small agricultural enterprise with modeling of the optimal distribution of energy resources for profits. INMATEH – Agricultural Engineering, 61(2), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.35633/inmateh-61-36

» https://doi.org/10.35633/inmateh-61-36 -

Tsytsiura, Y. H. (2020). Modular-vitality and ideotypical approach in evaluating the efficiency of construction of oilseed radish agrophytocenosises (Raphanus sativus var. oleifera Pers.). Agraarteadus, 31(2), 219-243. https://doi.org/10.15159/jas.20.27

» https://doi.org/10.15159/jas.20.27 -

Tsytsiura, Y. (2022) The influence of agroecological and agrotechnological factors on the generative development of oilseed radish (Raphanus sativus var. oleifera Metzg.). Agronomy Research 20(4): 842-880. https://doi.org/10.15159/ar.22.035

» https://doi.org/10.15159/ar.22.035 -

Tsytsiura, Y. (2023). Evaluation of oilseed radish (Raphanus sativus l. var. oleiformis Pers.) oil as a potential component of biofuels. Engenharia Agrícola, Jaboticabal, 43(SI), e20220137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1809-4430-Eng.Agric.v43nepe20220137/2023

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1809-4430-Eng.Agric.v43nepe20220137/2023 -

Tsytsiura, Y. (2024a). Evaluation of Ecological Adaptability of Oilseed Radish (Raphanus sativus L. var. oleiformis Pers.) Biopotential Realization in the System of Criteria for Multi-Service Cover Crop. Journal of Ecological Engineering, 25(7), 265-285. https://doi.org/10.12911/22998993/188603

» https://doi.org/10.12911/22998993/188603 -

Tsytsiura, Y. (2024b). Potential of oilseed radish (Raphanus sativus l. var. oleiformis Pers.) as a multi-service cover crop (MSCC). Agronomy Research, 22(2), 1026-1070. https://doi.org/10.15159/AR.24.086

» https://doi.org/10.15159/AR.24.086 -

Uddin, M. M., & Wright, M.M. (2023). Anaerobic digestion fundamentals, challenges, and technological advances. Physical Sciences Reviews, 8(9), 2819–2837. https://doi.org/10.1515/psr-2021-0068

» https://doi.org/10.1515/psr-2021-0068 -

Venslauskas, K., Navickas, K., Rubežius, M., Žalys, B., Gegeckas, A. (2024). Processing of Agricultural Residues with a High Concentration of Structural Carbohydrates into Biogas Using Selective Biological Products. Sustainability, 16(4), 1553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041553

» https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041553 -

Waithaka, S. (2023). Effects of Agriculture on the Environment. International Journal of Agriculture, 8, 10-20. https://doi.org/10.47604/ija.1933

» https://doi.org/10.47604/ija.1933 -

Xi, Z., Wang, W., Ping, Q., Wang, L., Pu, X., Wang, B., & Li, Y. (2023). Anaerobic Digestion of Phosphorus-Rich Sludge and Digested Sludge: Influence of Mixing Ratio and Acetic Acid. Separations, 10(10), 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations10100539

» https://doi.org/10.3390/separations10100539 -

Yang, L., Lamont, L. D., Liu, S., Guo, C., Stoner, S. (2023). A Review on Potential Biofuel Yields from Cover Crops. Fermentation, 9(10), 912. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation9100912

» https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation9100912 - Titei, V. (2022). The quality of fresh and ensiled biomass from white mustard, Sinapis alba, and its potential uses. Scientific Papers. Series A. Agronomy, 1(65), 559-566.

Edited by

-

Area Editor:

Juliana Lobo Paes

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

11 Apr 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

6 June 2024 -

Accepted

16 Feb 2025

ASSESSMENT OF OILSEED RADISH (Raphanus sativus L. var. oleiformis Pers.) PLANT BIOMASS AS A FEEDSTOCK FOR BIOGAS PRODUCTION

ASSESSMENT OF OILSEED RADISH (Raphanus sativus L. var. oleiformis Pers.) PLANT BIOMASS AS A FEEDSTOCK FOR BIOGAS PRODUCTION