Abstracts

The article addresses an endeavor by Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública (Sesp) to train folk midwives who worked in rural communities and to exercise control over these women's activities. The task was entrusted to the agency's prenatal and child hygiene programs, established between the 1940s and 1960s. The agency believed this training and control initiative would be of major importance in helping ensure the success of its project to establish local sanitary services offering mother-child assistance. The goal of working directly with the folk midwives was not only to force them to employ strict hygiene standards when delivering and caring for newborns but especially to use their influence and prestige within these communities to convince the general population to adopt good health practices.

midwives; hygiene; mother-child health; public health; Brazil

Discute as ações de treinamento e controle das parteiras curiosas promovidas pelo Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública, confiadas aos programas de higiene pré-natal e da criança, implantados entre as décadas de 1940 e 1960. Para os sanitaristas, o treinamento e controle das parteiras curiosas atuantes nas comunidades rurais brasileiras eram importantes para o sucesso do projeto de implantação de serviços sanitários locais de assistência materno-infantil. Ao atuar diretamente junto às parteiras curiosas, pretendia-se não somente lhes impor rigorosos padrões higiênicos na realização de partos e nos cuidados com os recém-nascidos, mas, sobretudo, recorrer a sua influência e seu prestígio naquelas comunidades para popularizar ações de saneamento.

parteiras; higiene; saúde materno-infantil; saúde pública; Brasil

ANALYSIS

The health education of folk midwives: Brazil's Special Public Health Service and mother-child assistance (1940-1960)

Tânia Maria de Almeida SilvaI; Luiz Otávio FerreiraII

IAssociate professor, School of Nursing, Universidade Estadual do Rio de Janeiro (Uerj). Rua Santa Cristina, 46/301, 20241-250 - Rio de Janeiro - RJ - Brazil. tanialmeida5@hotmail.com

IIResearcher, Casa de Oswaldo Cruz, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation; associate professor, Baixada Fluminense School of Education/Uerj. Rua Eng. Gama Lobo, 48/201, 20551-100 - Rio de Janeiro - RJ - Brazil. lotavio@fiocruz.br

ABSTRACT

The article addresses an endeavor by Brazil's Special Public Health Service (Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública/Sesp) to train folk midwives who worked in rural communities and to exercise control over these women's activities. The task was entrusted to the agency's prenatal and child hygiene programs, established between the 1940s and 1960s. The agency believed this training and control initiative would be of major importance in helping ensure the success of its project to establish local sanitary services offering mother-child assistance. The goal of working directly with the folk midwives was not only to force them to employ strict hygiene standards when delivering and caring for newborns but especially to use their influence and prestige within these communities to convince the general population to adopt good health practices.

Keywords: midwives; hygiene; mother-child health; public health; Brazil.

The Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública (Sesp; Special Public Health Service) has been the object of historiographic scholarship on the institutionalization of public health in Brazil, encompassing studies on the political, ideological, and particularly economic and military reasons behind its creation (Bastos, 1996; Campos, 2006; Pinheiro, 1992), the agency's public health initiatives in the control of contagious diseases like tuberculosis and malaria (Campos, 1999; Andrade, Hochman, 2007), and the training of human resources in the health field (Bastos, 1996; Campos, 2008). Starting in the 1950s, Sesp began devoting special attention to health education, especially in the sphere of mother-child assistance. The agency set up mother-child health assistance services throughout Brazil, including health posts, sub-posts, and Sesp hospitals. The first of these initiatives took place in municipalities in the Amazon region and Northeast Brazil, in the states of Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo (Vale do Rio Doce region), and in northern Goiás. In the 1960s, Sesp expanded its services into Southern Brazil, with a special focus on the northwestern area of Paraná (Bastos, 1996, p.165-190).1 1 Launched in January 1961, Projeto SC-FSP 35: Distritos Sanitários da Fronteira Sudoeste do Paraná (Sanitary Districts in Southwestern Paraná) was one of the cooperation projects signed in the 1960s by the government of the state of Paraná and Diretoria Regional do Sul da Fundação Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública (FSESP's Southern Regional Directorship; cf. Sesp, jan. 1961).

The present article describes and discusses Sesp-sponsored efforts to train and exercise control over folk midwives, known in Brazil as 'parteiras curiosas' or 'curiosas.'2 2 On traditional midwives in Brazil, see Nóbrega, Silva, 1970; Pereira, 1992; Dias, 2002. The prenatal hygiene and children's programs established by the agency were entrusted with training and supervising this traditional group of women. For health officials, these measures would be important in guaranteeing the success of the project to establish local mother-child assistance services. By working directly with folk midwives, Sesp intended to impose its own rigorous hygiene standards in delivery procedures and care for newborns, but also - indeed, above all - to use these women's influence and prestige within rural communities to encourage the public to embrace sanitary measures.

Health education and mother-child assistance

The March 1948 issue of Sesp's newsletter (Boletim do Sesp) spelled out the justifications for creating a health education program: this endeavor would be a "tool of the utmost importance in making the public understand the goal and scope of health programs and adopt good hygiene habits" (Sesp, mar. 1948, p.28).3 3 In this and other citations of texts from Portuguese, a free translation has been provided. The program would prepare a variety of teaching materials - movies, radio plays, pamphlets, posters, audiovisual slides - and distribute the educational material received from U.S. public health officials, which included 20,000 copies of "Higiene da gravidez" (Hygiene during pregnancy) and 5,000 of "Manual prático de ensino das parteiras" (Practical training manual for midwives).

According to Fonseca (1989, p.52-53), Sesp's view was that health education was primarily about replacing methods and practices that had imposed health values and rules from above (i.e., by the medical police) with teaching strategies believed more effective. Sesp's pedagogical methodology was meant to encourage public participation and to persuade families and communities of the value of preventive health measures. This investment in health education revolved around the principle of engaging all members of the healthcare team - physicians, nurses, sanitary aides, and visitadoras (a kind of community health worker) - who should in turn always involve communities in the solution of both individual and collective health problems.

Sesp's new style of approach was not without its contradictions and biases. For Campos (2006, p.231), the agency's "health education" model was rooted in value judgments that failed to hide a latent cultural conflict; that is, people's health troubles were blamed on popular culture, the source of "ignorance and bad habits." Concomitantly, it was assumed that health education, as a technical and scientific practice meant to disseminate hygienic values and habits, could transform people's customs and habits and improve their quality of life and their health.

For those in charge of Sesp's health education initiatives, the premise of ensuring favorable conditions for children's healthy growth and development, from pre-birth through the first years of life, justified institutional investment in a health program specifically targeting mother and children. To this end, prenatal hygiene services and children's services would need to be established at health posts.4 4 On the establishment of health centers and health posts in Brazil and the influence of the U.S. model, see Castro Santos, Faria, 2009. The teams rendering these services should comprise one nurse with specialization in public health and/or one public health visitadora and one physician. Further, it would be important for the doctor to be familiar with obstetrics and pediatrics, in addition to being qualified to act as a health educator, along with the nurse. Consonant with Sesp's strict professional hierarchy, both providers would be responsible for the "instruction of the mother, for care, and for supervision from early pregnancy through the postpartum period" (Sesp, mar. 1944, p.2).

The two key purposes of the mother-child hygiene program were to train and supervise folk midwives and to organize birthing services in the home, which was considered the best assistance alternative given the problems that pregnant and birthing women encountered in obtaining access to care, either because there were no doctors or there were no maternity hospitals. The supervision of folk midwives and the organization of at-home birthing services were endeavors that gave life to the health assistance program for mothers and children, forcing the physicians, nurses, visitadoras, and aides responsible for healthcare services in rural areas served by Sesp to "[raise] the general level of obstetric practice" (Sesp, mar. 1944, p.3).

Bastos (1996, p.178) explains how Sesp prioritized mother-child assistance right from the beginning of its operations, taking justification for this position from the following statistical portrait: 70.98% of Brazilians were women and children; the average infant mortality rate was estimated at 95 deaths per 1,000 live births, with the 0-4 age bracket heaviest hit; and most infant deaths could be avoided through medical and sanitary measures.

The June 1948 issue of Boletim do Sesp published a summary of the conclusions reached by the Brazilian and foreign technical specialists who attended Sesp's Conferência de Organização Sanitária (Health Organization Conference), held that month. One of the meeting's topics was the Programas Exequíveis de Saúde Pública (Feasible Public Health Programs), including therein the Programa de Higiene da Criança (Children's Hygiene Program), whose main purpose was to promote maternal health and the health of children up to the age of 14. Some of the recommendations were to "establish control over folk midwives in order to train them to stop employing practices considered harmful, promote the adoption of measures meant to improve the conditions under which they assist birthing, and [move to encompass] the puerperium period, even providing medical assistance when needed" (Sesp, jun. 1948, p.3).

Although we were unable to pinpoint the precise date when folk midwife training began, the documents we consulted suggest that activities commenced in 1946. The health education of folk midwives was part of an ambitious health education plan inaugurated by Sesp in August 1944 with creation of its Divisão de Educação Sanitária (Division of Health Education; Bastos, 1996, p.46; Sesp, jun. 1948). According to Nilo Chaves de Brito Bastos (1996, p.180, 405) - one of the Division of Health Education's pioneer public health officials - Sesp wanted to leverage the folk midwives' work and influence within communities in order to actualize the agency's projected mother-child assistance program. Sesp leaders thought folk midwives could be extremely useful in developing the mother-child health program, so long as they received specific training and were brought under the control of the agency's healthcare professionals.

At talks and other educational activities sponsored by Sesp, these midwives were part of the agency's prime target public, along with pregnant women and schoolchildren (Sesp, jun. 1948, p.28). By prioritizing the health education of this group, Sesp health officials intended to maximize the efficiency of the process of health education among rural populations, introducing healthy habits and values into family and school environments.

Discipline and teach: the training of folk midwives

Folk midwives were trained through practical activities of a technical and scientific nature, regular inspection visits, and instruction in appropriate health care for pregnant women and newborns. The task of training and supervising the midwives was entrusted directly to public health visitadoras and public health nurses,5 5 On the training of public health nurses, see Faria, 2006. with public health doctors sometimes taking part too.

Because it was a health education initiative, the teaching methodology included practical demonstrations, group discussions, film viewings, and the observation of healthcare providers at work. It was an ongoing training system, where theory was developed in small groups. The main program topics were the role of the midwife and the value of her work, personal hygiene notions, the importance of medical consultations from the outset of pregnancy, the importance of good nutrition during pregnancy, signs and symptoms of pregnancy, immunization against tetanus, midwife collaboration through the referral of pregnant women to government health services, complications in pregnancy, early signs of labor, initial care for newborns, assistance to women who have recently given birth, and the folk midwife's 'bag' (at the end of the course, any folk midwife who had passed would receive a bolsa, or bag, containing the material considered necessary for assisting with deliveries and caring for newborns) (Bastos, 1996, p.405-406).

After completing the first phase of training, midwives were assigned a health unit and came under the ongoing supervision of nurses and visitadoras. This did not imply any sort of formal tie between the midwives and Sesp, nor did they receive any type of payment for the supervised services they provided birthing women. In point of fact, even once trained these midwives continued to act as practitioners of a folk healing trade, typical of the small communities in Brazil's interior.

Under the supervision of visitadoras and public health nurses, the trained folk midwives would periodically receive new health instructions. The stated objective was to keep these Sesp collaborators abreast of new information but it was also a strategy for ascertaining whether or not they were adhering to the hygiene practices they had been taught. During training, midwives were expected to routinely participate in educational activities.

Tasks were assigned according to a hierarchy, with nurses responsible for the educational planning of midwife training and also for teaching both theoretical and practical classes, sometimes together with physicians. They also wrote up reports and supervised the midwife's bag. Visitadoras, who were more directly responsible for overseeing the midwives' work, routinely visited the homes both of midwives and of pregnant women to confirm whether the former were complying with Sesp recommendations.

Nurses and visitadoras were also responsible for identifying and recruiting folk midwives. According to a report submitted by nurse Lydia Duarte Damasceno to the director of Sesp's Programa da Amazônia (Amazon Program) in February 1946, this task evidently demanded patience and finesse, since the midwives avoided contact with health agents whenever possible: "I have not begun the classes for folk midwives because I was unable to identify any. We were only able to locate two, one of whom evades our visits, as she works at the hospital with doctors from the Territory, and the other failed to respond to our invitation. I spoke to Doctor Abdias about the matter, asking him to help the visitadoras in this regard, since I have not had time to get things underway" (Damasceno, fev. 1946, p.2).

The incident recounted by nurse Damasceno took place in Rio Branco, capital of the territory of Acre, where she spent some days in February 1946 organizing public health work to be carried out by the visitadoras in this city. Another interesting piece of information in her report concerns the midwife who worked with local physicians. Here is a fine illustration of the role midwives played in their communities, where their trade enjoyed broad social recognition, even by local doctors.

For folk midwives, one bonus of regular attendance at teaching sessions was their receipt of a bag containing sterilized material to be used during labor and delivery and in caring for newborns. The bags were a 'reward' for midwives who had shown interest and had performed well in class. A badge of distinction and power, this gift had a second purpose; Sesp nurses or visitadoras would periodically inspect the bag to see whether the folk midwives had been practicing the principles of hygiene they had been taught:

FOLK MIDWIVES (CURIOSAS): A course on the training and oversight of folk midwives has been established as an indispensable complement to prenatal services. Nurses Ana Branco and Dalmira Henrington are in charge. Midwives have shown an interest in this instruction and have been attending classes and referring pregnant women to health posts for medical care. The bags supplied by Sesp are inspected during classes with the goal of doing away with primitive customs. A vial of ash was found during one such inspection; this material is used to prevent human umbilical hemorrhages (in the thinking of folk midwives) (Sesp, mar. 1946).

After a midwife had completed her theoretical and practical training, she was subject to supervision according to a determined schedule, based on the deliveries she assisted and reported. Members of the nursing team would also visit the homes where deliveries had taken place. In addition, the visitadora or nurse would check for completion of a birth certificate in compliance with the model furnished by Sesp. Supervision also included the exchange of any unused sterilized material in the bag every ten days. Further, once a month the midwives were to present themselves at the health unit in order to have their materials cleaned and to receive new or updated instructions. A visitadora or nurse would also pay periodic visits to the midwife's home as a way of guaranteeing that she maintained ties with her assigned health unit (Bastos, 1996, p.405-406).

Sesp's official plan to transform these folk midwives into allies in the job of providing mother-child health assistance came up against a major obstacle, that is, the ideologies and values of the service's own public health agents. Much as Sesp heads recommended that their professionals establish a collaborative relationship with the midwives, in practice this is not what occurred. Because of their ideologies and professional values, doctors and nurses alike tended to view these women as a group that, rather than helping, actually hampered the success of health measures aimed at the mother-child population.

Doctors and nurses blamed the inefficacy of these specific health measures on the fact that the folk midwives clung to their ancestral customs, labeled primitive by the health agents. One of the customs that came under greatest criticism was treating the newborn's umbilical stump with ashes extracted from a herbal preparation. During the educational encounters attended by midwives, health officials relentlessly contested the women's predilection for this type of practice, grounded in popular beliefs and traditions.

For Sesp, the purpose of co-opting the midwives was eminently pragmatic, a way of saving time and reducing the energy that had to be invested in health education and assistance for rural populations. With their support, Sesp hoped to establish relationships of trust between health agents and rural populations, a fundamental prerequisite to the success of the agency's educational endeavors. Health officials believed that with the help of the midwives they could draw a large clientele to their facilities. In the eyes of agency managers, the midwife constituted a strategic link in this relation. The words of public health doctor Marcolino Candau - superintendent of Sesp from 1947 to 1950 (Bastos, 1996, p.523) - serve to illustrate this point. Speaking at the seminar Prenatal Hygiene and the Child, held at the Brazil-United States Institute, Doctor Candau said:

The man from the interior is much more an individualist than the man from the city. He is used to solving his own problems. We must not forget the old curiosa who was present at his grandmother's delivery, and at his mother's, and will be there for his daughter's. We must make this midwife our ally. With her help, 80% of the births in Aimorés are reported. [The midwives] do not improve much with training but at least they maintain a tight bond with the hygiene post. Until we can instill in people an unquestioning trust in the health post, we are going to need these folk midwives (Sesp, jan. 1949b, p.10).

Marcolino Candau's attitude, both tolerant and pragmatic, nevertheless did not reflect the unanimous opinion of Sesp agents. A few months after his statement, a brief unsigned note was published in another issue of Boletim do Sesp, expressing a slightly different value judgment about these folk midwives:

It is not enough to make amends; we must avoid other evils. Hence the proliferation of educational courses, including those for injurious midwives, whose misconduct contributes to Brazil's daily mortality rate of 2,040 children. Given by physicians and nurses in the Amazon, instructional courses for folk midwives - so-called comadres - have reached 50, with 850 midwives enrolled. As a complement to the sanitation campaign, where there are no sewer networks Brazilian doctors have ordered ditches to be dug, which total 7,600. Now, reader, given all the misery laid out in this article, what would be of the Amazon if there was no more Special Public Health Service? (Sesp, maio 1949, p.6).

Although the purpose of this note was to extol the praises of Sesp at a time when institutional projects were threatened by a dearth of budgetary funds to ensure continuation of the bilateral agreement with United States,6 6 The May 1949 issue of Boletim do Sesp offered a detailed report about the threat that Sesp services might be abolished; as a consequence, the agency's projects and services were continued and even expanded. we can observe how the discourse of public health officials identified folk midwives as one of the social ills ravaging the agency's territories.

In 1954, Boletim do Sesp published information on the Curso de Aperfeiçoamento Para Parteiras Curiosas (Advanced Course for Folk Midwives). The article sheds light on the pragmatic goals, cultural biases, and persuasion strategies adopted by health agents in their efforts to train and exercise control over the hygienic practices of these midwives:

From the very start of its work, Sesp has endeavored to improve the level of knowledge of folk midwives, instructing them in notions of the hygiene and care that should be given pregnant and birthing women and by newborns. Through an educational program involving regular classes at Health Units, Sesp has been able to rapidly transform these midwives - by and large matured and negligent people whose unpleasant appearance alone signals their total lack of hygiene - into zealous professionals, possessing salutary habits. Sesp's first step is to survey the number of midwives working in the area in question, generally gathering their names and addresses from pregnant women themselves. Next comes the catechizing, when nurses or visitadoras attempt to contact the midwives and invite them to attend the course sponsored by the Unit, since the instruction offered there is as useful for them as it is for pregnant women and newborns. . . .In addition to the immediate benefits for the health of pregnant women and newborns, there are other advantages to be gained from teaching the midwives; the mere fact that the child's birth will be reported to the Service is something in itself, if we bear in mind that this will allow the Unit doctor to oversee this child's development (Sesp, maio 1954, p.3-4; emphasis added).

If the training of folk midwives was a frequent topic in Sesp newsletters, another was the agency's initiative to train and further develop its own staff in the fields of mother-child hygiene and obstetrics, in clear counterpoint to folk midwife training. The bulletin reported that efforts in the field of mother-child assistance took two directions: health education, where the training of midwives came in, and professional specialization, with investments in the medical and scientific development and training of the agency's own staff.

These investments in the training of specialists in mother-child hygiene and obstetrics undoubtedly reflect Sesp's intention to foster the medicalization and hospitalization of birth, in accordance with local possibilities. In this respect, the motivations behind the agency's introduction of midwife training programs differed from the motivations behind its forming a staff of specialists with advanced technical and scientific skills. Sesp gave the trained folk midwives a bag but offered no payment for services rendered, while its health personnel - nurses and doctors - were granted another kind of gift: a scholarship to undertake specialization studies in obstetrics (Sesp, mar. 1961, p.4). In the early 1960s, the following individuals were receiving scholarships from the Fundação Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública (FSESP; Special Public Health Service Foundation):7 7 After a 1960 change in Sesp by-laws, the agency was transformed into the Special Public Health Service Foundation (Fsesp). This institutional restructuring has been described by Nilo Chaves de Brito Bastos (1996, p.143-145). Domingos da Silva Santos, a physician working with the Diretoria Regional do Amazonas (Amazon Regional Directorship), who was studying obstetrics at the Das Clínicas and São Paulo hospitals; and the nurses Cândida Fernandes and Maria de Lourdes Rodrigues, who worked with the Serviço Cooperativo de Saúde do Rio Grande do Norte (Rio Grande do Norte Cooperative Health Service) and with the Superintendence, respectively, both specializing in obstetrics (the former was studying at the Escola de Enfermagem da Bahia [Bahia School of Nursing] and the latter, at São Paulo Hospital).

Ethnocentrism in health

A contrasting view of the social role of folk midwives as held by health professionals is found in the book Aimorés: análise antropológica de um programa de saúde (1959) by Luiz Fernando Raposo Fontenelle, an anthropologist hired in 1956 to conduct social research in communities served by Sesp.

The decision to contract Fontenelle's services was part of the agency's move to incorporate social science studies as part of the strategies of the Division of Health Education, with the 1953 establishment of the Seção de Pesquisa Social (Social Research Section), headed by sociologist Arthur Rios. The goal was to persuade public health physicians, public health nurses, and visitadoras of the eminently social nature of the concepts of health and disease, considering that the people in the communities served by Sesp had their own values and practices and that these had to be taken into account. A second goal was to convey to the health officials working for Sesp an anthropological understanding of local populations' traditional culture (Campos, 2006, p.232).

In the municipality of Aimorés, in Minas Gerais, Fontenelle had the rare opportunity to observe and analyze popular knowledge and practices in health and disease and to witness the antagonistic relations between folk therapists and the agents of scientific medicine. In his dialogue with public health workers, the anthropologist asked them to be aware of the existence of a popular medical culture whose well-structured practices reflected a set of beliefs that were not - contrary to the general assumption - simply manifestations of ignorance and superstition. He argued that it was essential for these health workers to display an understanding attitude about popular practices if their civilizing endeavor was to achieve success:8 8 In the 1940s, Florestan Fernandes (1960, p.106-162) conducted a study similar to Fontenelle's, focusing on the health status of interior Brazil and the clash between scientific and popular medicine. Fernandes based his work on information and data provided by Fontenelle, as found in his book Viagem ao Tocantins, published in 1946.

Uncovering the general lines of Popular Medicine within a region of Brazil will facilitate the fruitful efforts that may in the future result from the activities of Public Health services. We must bear carefully in mind the need to shape a more understanding mentality and policy towards components of the Popular Medicine system, its planned use for specific purposes, and, most importantly, an awareness of the fact that sanitary problems in rural areas intertwine with the economic and social situation of their inhabitants (Fontenelle, 1959, p.9).

Fontenelle (1959) observed that relations between midwives and Sesp representatives were generally quite strained. Attempts by public health officials to educate midwives about their practices did not produce the expected results. Attendance was low at training sessions, and the obstacles encountered in getting midwives to incorporate new hygiene techniques and behavior made for tense relations between them and the visitadoras and nurses. For the midwives, the training process constituted a form of control that constrained their activities and left them vulnerable to unwelcome criticisms by health agents.

In his analysis of this uncomfortable situation, Fontenelle (1959) identified certain factors that made it harder for midwives to embrace sanitary ideas and practices: their average age, which was generally more advanced; problems getting to health facilities; and their disagreement with the recommended guidelines of scientific medicine. Further, the author pointed out that these midwives received no economic compensation for attending training sessions. They had to run the risk of losing a client should they be called to a birth while at class, and this represented a financial loss since the families of their clients paid them. This is not to say that they earned a great deal, as fees were negotiated and depended upon each family's economic means.

Fontenelle (1959) also emphasized that the impasses between midwives and Sesp representatives stemmed from the contradiction between the precepts and practices of folk medicine and those of scientific medicine. As an example of this culture clash, he cited the matter of the woman's birthing position. In the opinion of obstetric science, the woman should be in a horizontal position, lying on her back in bed, while in midwifery practice she should be vertical, seated on an appropriate bench or chair. Other typical midwifery practices and customs were the cause of frequent conflicts with public health agents: the type of food prescribed the mother-to-be or new mother; the use of infusions, baths, and body massages; treatment of the newborn's umbilical cord with special formulas, and so on.

According to Fontenelle (1959), compounding these cultural differences, the controls placed on folk midwives contributed to their low commitment to the process of health education for mother-child care. During 1956, that is, the period when he conducted his research in Aimorés, the anthropologist found that of the twenty-two folk midwives registered with Sesp's health unit, only four had attended all of the classes given in February.

Institutional ethnocentrism aside, Sesp inarguably made good use of the work of these midwives, as shown by the performance recorded in quarterly progress reports. These documents present interesting data on mother-child assistance delivered within the scope of Sesp health programs. Drawn from reports on Sesp's Amazon, Northeast, Bahia, and Rio Doce Programs for the second quarter of 1951, Tables 1, 2, and 3 summarize information on the number of folk midwives identified in each region, the most common types of birthing care provided, and the type of attending provider.

Table 1 shows that a high proportion of the identified community midwives were registered with Sesp mother-child assistance programs, allowing us to advance a preliminary evaluation of the agency's recruitment capacity. Although these records cannot speak to the efficacy of health education, it is still relevant to know that Sesp maintained contact with a good share of the folk midwives working in the places where mother-child assistance activities were being conducted.

The information in Table 2 lets us conclude that most deliveries took place outside the hospital, presumably in the home of the mother or her family. This confirms that in the early 1950s in the regions where Sesp was present, childbirth was still primarily a household event, tied to cultural values and practices lying outside the realm of scientific medicine.

Lastly, Table 3 affirms the folk midwife's social role as a protagonist in the childbirth culture prevalent in communities served by Sesp, given that the absolute majority of deliveries were attended by these traditional practitioners. These figures highlight the irrelevance of obstetric medicine as a technique for assisting childbirth in these regions and underscore the importance of the midwife as an intermediary between Sesp and rural populations.

Folk midwives through images

Sesp provided midwife training in a gamut of social and regional contexts, stretching from northern to southern Brazil. Instruction was offered from the 1940s through the 1960s, the period of the agency's greatest activity, and detailed reports were issued on this work. As with other documents produced by Sesp staff, these records systematically included photographs. There are indications that the large collection of images produced by Sesp down through its history was a central component of its institutional pedagogy and publicity, especially in the field of health education.

The photographs presented here record moments of camaraderie between folk midwives and the professionals in charge of their training and direct supervision, that is, public health visitadoras. They illustrate not only Sesp's activities and the type of education offered during this vocational training but also the social spaces where the institution's health agents and the folk midwives interacted.

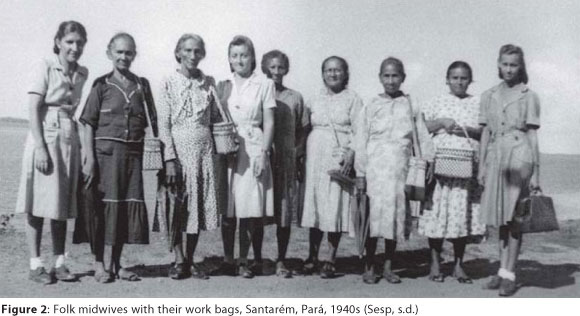

Figures 1, 2, and 3 depict folk midwives trained in the Brazilian Amazon in the 1940s. The next two figures illustrate the training of midwives by FSESP in the 1960s in southern Brazil. Pictures of folk midwives are not plentiful, compared with those of visitadoras and other ancillary groups, as shown by Tânia M. Almeida Silva (2010, p.168-200).

Figure 1 portrays folk midwives, visitadoras, and a physician, gathered in a semicircle in a large room. Capturing the inside of a domestic space, where we can spot typical decorative items, this scene serves to exemplify sociability and some degree of camaraderie between public health agents and midwives, which is what Sesp's educational proposal aimed at. Note how the physician - the only man in the group - and the visitadora occupy center stage, seated side-by-side in the middle of the photograph. To their left and right, we see folk midwives next to uniformed visitadoras, probably students at the training course. The positioning of these figures in the photograph reproduces the hierarchy inside the agency. The doctor and nurse, for example, are part of the group known within the agency as 'professional staff,' eligible to hold administrative posts with leadership duties. The visitadoras were considered part of ancillary personnel, subject to following the orders of a physician and/or nurse. Folk midwives were members of the local community and of course not part of Sesp staff. The caption tells us that midwives attended weekly classes given by the visitadoras or doctor. However, there is no way of knowing whether the home-like setting chosen for this photograph was actually the place where classes were held or whether it was chosen precisely to convey an atmosphere of camaraderie.

Figure 2 captures a moment during a training session given by the visitadoras (in uniform). In plain sight are the midwives' bags, which, as mentioned earlier, were given out after the women completed the first phase of their training. The caption explains that these bags contain material essential for deliveries.

By recording these moments of interaction between midwives and health agents, it was Sesp's intent to document the standard procedures in midwife training. This helps explain the attention placed on the midwife's bag, a symbolically noteworthy artifact that endowed its bearer with special status, distinguishing her from non-trained midwives and attesting that the health agency had officially recognized her as a 'professional.'

The images produced by Sesp also highlighted the hygiene techniques considered indispensable in assisting deliveries and caring for newborns, as illustrated in Figure 3 . The caption explains that during midwife training, visitadoras demonstrated a simple technique for hand washing, intended to prevent contamination and its consequences. This image and its caption dialogue with the view held by representatives of scientific medicine, who cast blame for the infections contracted by birthing mothers and newborns on the non-sterile hands of midwives (Silva, 2010).

The images reproduced in Figure 4 register the training received by folk midwives at the Projeto Para os Distritos Sanitários da Fronteira Sudoeste do Paraná (Project for Public Health Districts in Southwestern Paraná), conducted in the early 1960s under a cooperation agreement between the state government and FSESP. The images were undoubtedly placed side-by-side in the original document for a well-defined reason. The caption tells us that the child in photograph 1 is being attended to by the health unit's physician, while photograph 2 depicts a practical class for folk midwives at a different health unit, once again drawing attention to care for the child. The organization of this photographic record illustrates the importance accorded assistance for children, as advocated by Sesp health officials from the agency's earliest days (Bastos, 1996). One of the teaching tools used by Sesp health officials was repeated demonstrations of the same procedure, so the midwives would learn it by heart.

Resembling a typical graduation photo, the last picture shows the folk midwives who had 'graduated' from the course at the Pato Branco Health Unit in the state of Paraná (Figure 5). In the front row we see a nurse in a white uniform next two to visitadoras, likewise wearing their official uniforms. The trained midwives are in the back.

The uniform is an important element of distinction and identity for corporations of healthcare providers. In these visual records of female professional groups involved with Sesp projects, we observe a contrast between the impeccable use of uniforms by the agency's direct representatives and the non-standardized dress of the folk midwives. Although female representatives were quite strict in their oversight of the midwife's bag, we found no documental records related to the matter of the group's dress.

Although the photographs of folk midwives from the Amazon and of those from southern Brazil were taken at different dates and express some clear regional differences, certain common traits are discernable in the pictures, especially regarding the women's ages, most of them being either middle-aged or elderly. Here we observe a contrast between the midwives in general and the groups of visitadoras and nurses, the latter apparently from a younger age bracket. Along with educational level and social class of origin, this feature differentiates the two groups of women: on the one hand, the representatives of scientific medicine (nurses and visitadoras); on the other, those of popular medicine (folk midwives).

Final considerations

The relationship established between Sesp and folk midwives was mediated by strategies in health education and had as its goal the cultural assimilation of these women, with the hope of transforming them into participants in the agency-led project. One singularity of the adopted model of health education was the recognition that it was necessary to be familiar with the values and practices of health and disease as expressed - in the case of our example - by the midwives that worked in their communities.

Sesp's strategy can to some extent be considered relational. Public health medicine wanted to impose its authority through apparently reciprocal interactions with another culture of health and disease, which we could call 'native.' We can gain a much better understanding of Sesp's approach towards folk midwives if we consider it from the perspective of 'anti-conquest,' to borrow a concept proposed by Mary Louise Pratt (1999, p.77-153). In her analysis of the conduct and approach used by the naturalists and travelers who were representatives of European culture in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century African and American colonial contexts, Pratt calls attention to their practices of appropriating the Other by learning about his material and cultural goods. As exercises in symbolic violence, this approach was intended to demonstrate one culture's superiority over another and thus permit the domination of social groups that were deemed inferior, incorporating some of their social habits and concepts while assigning them new uses and meanings.

In the case addressed in this article, the strategy of anti-conquest is manifested in the idea that one must win the midwife's trust and become familiar with her belief system, practices, and clientele; train her to perform her work in compliance with the methods and principles of public health medicine; and later appropriate and modify her trade, and the space where she conducts her activities, to harmonize with other cultural patterns. In this context, folk midwives were seen as a social group that obstructed the path of public health actions. However, these women should not be fought head on but instead converted into allies so that the agency could make the greatest possible use of their prestige and influence within the communities being served. Sesp's intent was to realize health education among the country's rural populations while simultaneously transforming traditional health care into a public health endeavor - which is not to say that this was not a way of exercising control over midwives.

NOTES

REFERENCES

- ANDRADE, Rômulo de Paula; HOCHMAN, Gilberto. O plano de saneamento da Amazônia (1940-1942). História, Ciências, Saúde - Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, v.14, supl., p.257-277. 2007.

- BASTOS, Nilo Chaves de Brito. SESP/FSESP: 1942 - evolução histórica - 1991. Brasília: Fundação Nacional de Saúde. 1996.

- CAMPOS, André Luiz Vieira de. Cooperação internacional em saúde: o Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública e seu Programa de Enfermagem. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, Rio de Janeiro, v.13, p.879-888. 2008.

- CAMPOS, André Luiz Vieira de. Políticas internacionais de saúde na era Vargas: o Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública, 1942-1960. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fiocruz. 2006.

- CAMPOS, André Luiz Vieira de. Combatendo nazistas e mosquitos: militares norte-americanos no Nordeste brasileiro, 1941-1945. História, Ciências, Saúde - Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, v.3, n.3, p.603-620. 1999.

- CASTRO SANTOS, Luiz Antonio; FARIA, Lina. Os primeiros centros de saúde nos Estados Unidos e no Brasil: um estudo comparado. In: Castro Santos, Luiz Antonio; Faria, Lina. Saúde & História São Paulo: Hucitec. p.154-186. 2009.

- DAMASCENO, Lydia Duarte. Relatório do mês de fevereiro de 1946. Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública. AM - ITA-12B. Fundo Sesp I, cx.11, doc.12. (Casa de Oswaldo Cruz/Fiocruz). fev. 1946.

- DIAS, Maria Djair. Mãos que acolhem vidas: as parteiras tradicionais no cuidado durante o nascimento em uma comunidade nordestina. Tese (Doutorado) - Escola de Enfermagem, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. 2002.

- FARIA, Lina. Educadoras sanitárias e enfermeiras de saúde pública: identidades profissionais em construção. Cadernos Pagu, Campinas, v.27, p.173-212. 2006.

- FERNANDES, Florestan. Mudanças sociais no Brasil: aspectos do desenvolvimento da sociedade brasileira. São Paulo: Difusão Européia do Livro. 1960.

- FONSECA, Cristina Maria Oliveira. As propostas do SESP para educação em saúde na década de 1950: uma concepção de saúde e sociedade. Cadernos da Casa de Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, v.1, n.1, p.51-58. 1989.

- FONTENELLE, Luiz Fernando Raposo. Aimorés: análise antropológica de um programa de saúde. S.l.: Dasp. 1959.

- NÓBREGA, Maria do Rosário Souto; SILVA, Damaris Dias da. Descoberta, treinamento e controle de parteiras curiosas: uma necessidade no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, Brasília, v.22, n.1-2, p.80-93. 1970.

- PEREIRA, Maria Luiza Garnelo. Fazendo parto, fazendo vida: doença, reprodução e percepção de gênero na Amazônia. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Faculdade de Ciências Sociais, Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo. 1992.

- PINHEIRO, Themis Xavier de Albuquerque. Saúde pública, burocracia e ideologia: um estudo sobre o SESP (1942-1974). Dissertação (Mestrado) - Faculdade de Administração, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal. 1992.

- PRATT, Mary Louise. Os olhos do Império: relatos de viagem e transculturação. Bauru: EdUsc. 1999.

- SESP. Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública. Boletim do Sesp, s.l., n.3. mar. 1961.

- SESP. Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública. Boletim do Sesp, s.l., n.5. maio 1954.

- SESP. Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública. Boletim do Sesp, s.l., n.71. maio 1949.

- SESP. Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública. Boletim do Sesp, s.l., n.67. jan. 1949.

- SESP. Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública. Boletim do Sesp, s.l., n.60. jun. 1948.

- SESP. Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública. Boletim do Sesp, s.l., n. esp. mar. 1948.

- SESP. Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública. Boletim do Sesp, s.l., n.7, mar. 1944.

- SESP. Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública. Curso Para Visitadoras Sanitárias, Santarém, PA. Projeto AM-SAN-12B, 1944/1947. Relatório do mês de março de 1946: AM-SAN-12-B. Fundo Sesp I, cx.14, doc.43. (Casa de Oswaldo Cruz/Fiocruz). mar. 1946.

- SESP. Serviço Fundação Especial de Saúde Pública. Projeto SC-FSP 35: Distritos Sanitários da Fronteira Sudoeste do Paraná. Fundo Sesp I, seção 2 (docs. diversos), dossiê 1, cx.8, pasta 2, doc.71. (Casa de Oswaldo Cruz/Fiocruz). jan. 1961.

- SESP. Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública. Relatório do Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública: Higiene Materna. Fundo Sesp, cx.92, doc.2. (Casa de Oswaldo Cruz/Fiocruz). 2. trim. 1951.

- SESP. Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública. Curso Para Visitadoras Sanitárias. Santarém, PA, 1944/47. Recordações do Projeto. Fundo Sesp I, cx.14, doc.43. (Casa de Oswaldo Cruz/Fiocruz). s.d.

- SILVA, Tânia Maria de Almeida. Curiosas, obstetrizes, enfermeiras obstétricas: a presença das parteiras na saúde pública brasileira (1930-1972). Tese (Doutorado) - Casa de Oswaldo Cruz/Fiocruz, Rio de Janeiro. 2010.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

20 Jan 2012 -

Date of issue

Dec 2011

History

-

Received

Apr 2011 -

Accepted

Sept 2011