Abstracts

This paper deals with an underlying problem in the Brazilian school system which affects the teaching and learning of history - students' illiteracy. As this subject is based on written texts, history teachers' expectations of their students' literacy levels will directly impact on their choice of texts and the history they teach in the classroom. The paper presents an analysis based on language studies and written history in an effort to raise the problem of illiteracy in Brazil and to contribute to its discussion in other areas. Finally, some alternatives for the teaching of history in primary schools are presented.

history teaching; literacy; writing

Este texto trata de um problema existente na escola brasileira que afeta diretamente o trabalho de ensino e aprendizagem de história: as condições de seus alunos no que se refere ao domínio da leitura e da escrita. Sendo a história, inclusive a escolar, pautada na escrita, as expectativas dos professores acerca de seu domínio pelos alunos definem diretamente suas escolhas didáticas e a história que lhes apresentam nas aulas. O texto apresenta uma análise pautada nos Estudos da Linguagem e na história da escrita, visando contribuir para a visibilidade do problema além dos muros da escola e para sua discussão em outras bases. Com base nisso, considerando o quadro apresentado, sinaliza algumas alternativas para o ensino de história no Ensino Básico.

ensino-aprendizagem de história; letramento; escrita

DOSSIER: HISTORY, EDUCATION AND INTERDISCIPLINARITY

Writing skills as a condition for the teaching and learning of history

Helenice Aparecida Bastos RochaI

Associate Professor, Faculdade de Formação de Professores, Universidade Estadual do Rio de Janeiro. Rua Francisco Portella, 1470. 24435-005 São Gonçalo - RJ - Brasil. helarocha@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This paper deals with an underlying problem in the Brazilian school system which affects the teaching and learning of history - students' illiteracy. As this subject is based on written texts, history teachers' expectations of their students' literacy levels will directly impact on their choice of texts and the history they teach in the classroom. The paper presents an analysis based on language studies and written history in an effort to raise the problem of illiteracy in Brazil and to contribute to its discussion in other areas. Finally, some alternatives for the teaching of history in primary schools are presented.

Keywords: history teaching; literacy; writing.

In Brazilian schools, especially public ones, a recurrent problem highlighted by history teachers is that of teaching the subject to students who are not properly literate. This is understood here in its instrumental meaning, involving competence in reading and writing. It is a cause of wonder and complaints among teachers, and researchers, and reflects on the actual relationship that teachers have with their students. Together with other conditions, such as whether or not there exist writing materials for use in the classroom (books or reproductions of texts on pages), the representations of the characteristics of a student as more or less lettered direct the teacher towards determined didactic choices, which involve in turn, a more or less problematizing treatment of the history it is intended to teach. Furthermore, they collaborate to shape a certain relationship with writing in the classroom.

Initially, I will present a brief analysis of the situation of Brazilian students in relation to their mastery of writing based on data obtained in the performance evaluation instruments prepared by the Ministry of Education. I also discuss the expectation of history teachers in relation to students from the old fifth grade of primary school, now the sixth class.

In the second part I will look at elements from the history of writing and the argument about the existence of a rationality of writing which orientates cognition and the formation of identities. In the same section, based on the explanation routinely given by teachers for the problem, I will present relations between literacy and education. I problematize this explanation using the concept of letramento (being able to read and write, or being lettered), evaluating its relevance for the case of teaching and of learning in school history.

In the third part I present fragments of extracts from history classes, registered in field work, in which the language is present in the oral or written modality. These fragments function as examples of the situation of the teaching of history in which teachers outline their representations of students in relation to letramento. I seek to show the history that is constituted in this games of practices and representations that delimitate the decisions of the teachers.

THE MAGNITUDE OF THE PROBLEM: WHAT THE SAEB NUMBERS SAY

In 2004 the figures of the National Evaluation System of Primary Education (Sistema Nacional de Avaliação do Ensino Básico - Saeb)

The use of the results of the National Evaluation System of Primary Education (Saeb) gives a magnitude to the problem experienced by teachers in the classroom. I work with figures that discriminate the achievements of students in public and private schools, since the complaint usually presented refers especially to public school students. As we will see, there are actually relevant differences in student performance in the two networks in relation to their reading competence.

It is worth noting that Saeb, like the other evaluation instruments created in the 1990s,

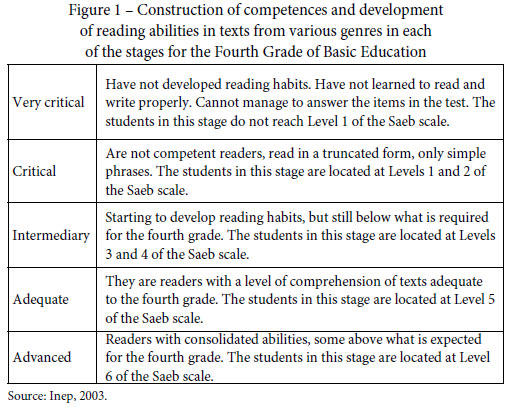

Let us look at the description of the students found at each level of the evaluation of proficiency in Portuguese. These indicators summarize the expectation descriptors for reading competence in the Reference Matrices for Portuguese and function as a parameter for the discussion proposed here of writing (including reading) as a necessary condition for the teaching and learning of history.

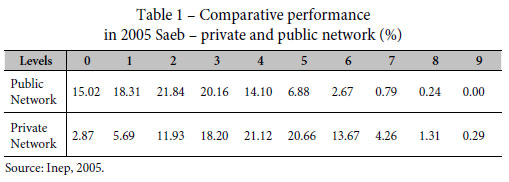

I present below a comparison between the levels of evaluation of proficiency in Portuguese, with an emphasis on the reading capacity of students, in public and private networks at the end of the fourth grade, from the 2005 Saeb. The analysis will be based on the specifications presented in Figure 1. This percentage refers to the approximate number of 18,465,505 students in this grade, according to the 2005 School Census. Of these, 16,652,806 were in public school and 1,812,699 in the private school network.

In 2005, 55.17% of public school students had a critical or very critical performance, referring to the total percentage of levels 0, 1 and 2. This percentage contains illiterate or precariously literate students, who can read and write in a rudimentary manner insufficient to continue with their school trajectory. With the addition of level 3, students whose performance in reading was unsatisfactory comes to 75.33% of those who did the test. In 2005 three quarters of students in Brazilian public schools were still unable to properly read or understand based on writing and to write what was asked of them in school subjects, including history.

The intermediate group is divided into levels 3 and 4. Taken together they amount to 34.26% of public school students who are still beginning to read proficiently. Levels 0-4 account for 89.43% of students. In other words, in 2005 approximately 90% of students did not meet educational expectations of mastering writing as a prior learning which would help them continue their studies in an adequate manner. On the other hand, the subtotal of students with adequate performance or better was 10.58%. A little more than 10% of public school students were at levels considered adequate to continue with their studies at the end of the fourth grade.

In the private network in 2005, 20.49% of students were critical or very critical (levels 0 -2), around 34% less than public school. The greatest concentration of performance in this network was between levels 3 and 6, with 73.65% of students being intermediate, adequate or advanced at the end of the segment. Levels 3 and 4, considered intermediate, accounted for 39.32% of the performance of students, against 34.26% in the public system. In 2005, among the levels which indicated an intermediary, adequate, or better performance, the private network had 73.65% of students against 44.84% of public students.

The sum of the subtotals of level 5 and above results in 40.19% of students in the private network being considered adequate or better to continue their studies in relation to their mastery of reading and writing. This is also a concerning percentage, but indicates better learning conditions with a much more significant part of the students of this network can make full use of writing than public school students, where the equivalent figure is 10.58%.

Effectively, even within each network, there are differences that stimulate or hinder the work of the teacher which includes writing as a form of access to knowledge. In the public network, federal schools traditionally obtain better results than state and municipal ones. In the private network this variation is attributed, amongst other factors, to the relationship between the acquisitive power of students' parents and the services offered by the school. Taking into account the total number of students per network, 16,652,806 in public school and 1,812,699 in the private network, these characteristics and differences produce results that are even more perverse for most Brazilian schools...

In a brief analysis of the numbers of the 2005 Saeb we can see that the insistence of teachers, especially from public schools, in highlighting students' lack of conditions to learn their specific discipline, due to their reading and writing abilities, is something that cannot be ignored in the discussion of the teaching of history. How can this serious finding be inserted in the teaching of history which depends on writing to be made effective? After all, can a student in the final years of Basic Education still not be sufficiently literate to learn history?

This scenario can only be altered slowly, through policies continued in the first years of the twenty-first century, with targets that point to a gradual improvement over the coming decade. Thus, it is necessary to simultaneously seek to resolve the problem of the students of our schools entering the world of writing and to adapt actions to the problems which still persist regarding educational policies, including those related to the school curriculum; the training of history teachers, the methodological choices of teachers; and studies on the teaching and learning of history, a school discipline that is constituted with a strong relationship with writing.

Let us now look at some points related to the history of writing, of literacy and letramento, with the aim of arguing for the need to denaturalize some of our beliefs, including the existence of a rationality of writing, one with a universal nature.

LEARNING TO WRITE AND LEARNING WITH WRITING

The ability to write is a prerequisite for learning school subjects in the final years of Basic Education. In other words, after learning to read and to write in the early years, students should learn the existing knowledge through writing. History teachers, like the lettered people they are, share this expectation constructed during the history of education in the western world, in which, parallel to the exponential growth of knowledge registered in a written form,

Some notes on the history of writing in the West

In Western countries education is organized in a form that the schools are initially concerned with the learning of reading, writing and counting, while the college becomes the space of that part of society who already have knowledge and can continue with their studies, which means having access to knowledge organized in written supports. The association that is made between knowledge and writing is prepared like a type of rationality of writing. The capacity to learn knowledge that is already structured is gradually and definitively associated with the capacity to read, to write and to count in the same order.

As a background discussion to this school expectation, there are different positions about the predominance of orality and writing in human cognitive development and its effects on learning. In this text we do not intend to present a history of writing or reading in the West, but rather to situate a debate, which is contemporaneous, about the power of writing in relation to cognition and rationality and about those who contest this power. In this debate scholars have meticulously examined history in search of a moment or moments in which writing has given rise to new forms of the organization of knowledge. As we will see in the brief summary of these ideas, they are related to distinct social relations of the people, whether lettered or not, who extrapolate this research.

For some writing corresponds to the spoken word put down in writing. Since Antiquity this had been developed, with the register of epic orality, in which actions and passions were described.

In the Renaissance the growth of cities exposed European man to challenges related to the decontextualization of information. He needed to interact with information and people at a distance, in an ever more complex form, at a time of great scientific and technological development, exemplified in the navigations, the architecture of cathedrals and transformations in agriculture. According to Denny, decontextualization is the handling of information in order to place it in different planes. One of these operations with information is graphic representation. Writing is thus one of the developments of the registers that decontextualize information, such as the preparation of maps, blueprints of large constructions, technical navigation instruments and agriculture.

The greatest controversy among authors is related to the defense (or critique) of writing as an impulse for the development of a rationality, based on the more or less formal and abstract thinking of written or unwritten societies. Denny, based on historical psychology, presents this discussion and argues that in all human societies, whether oral or written, there exists formal and abstract thinking. However, based on studies of the emergence of writing (in Antiquity or in the Renaissance), he states that writing results from a decontextualized environment.

Let us look at the example of a child from the current day. Seeing the name of his mother written in the same form as the name of another person with the same name, he rejects the possibility that this writing represents the name of more than one person. He sees the names as a property of his mother. He still does not see writing as a tool to make decontextualized abstractions.

The lists of the dead, or food in royal storehouses studied by Goody, show an abstraction, which is the inscription of a set formed of various names by some classification criteria on a list, and decontextualize these beings, dead or foodstuffs, from their immediate context. Similarly, on the synthetic plane, a characteristic of oral language is greater contextualization (depending on various factors, such as the predominant type of discourse), and of written language great decontextualization, on a continuum. The verbal use of subordinate conjunctions such as when, while and why among phrases also establishes a hierarchized separation between information, constituting decontextualized verbal abstractions.

The decontextualized abstraction of a type of rationality is thus a consequence of the social scenario from which writing is said to have emerged, and with its dissemination in the history of education, it was constituted as school expectation.

In a critical vision of the advantages of the predominance of writing over orality, or the benefits involved, Street sees in authors such as Greenfield, Hildyard, Olson and Havellock an ethnocentric position. Street criticizes their positions because they establish a great divide between the thought processes of different social groups: the literate and the non-literate, for example.

The proposal of a great divide between written and non-written societies that Olson, Havellock and others defend, with differences regarding the extent they reach about the advantage of orality as a form of rationality, is constituted in an argument which takes Western Europe as the paradigm for the evolution of writing for the rest of the world. Moments are established in which the human enterprise (read the Western European enterprise) involved, among other aspects, the development of language as representation and decontextualized abstraction, and the development of writing in tension with orality.

History also participated in this organization of knowledge in the wake of written culture as the reference of the rationality of the West, with the characteristics that it constructed for itself as the field of knowledge that uses writing. The writing of history is what structures it as a discipline in the framework of the naturalization of the rationality of writing. According to Michel de Certeau, history is an operation about a discourse. In this line of reasoning, the profession of historian is a scriptural exercise.

Learning history not only orders previous knowledge of reading and writing, but orders the mastery of reading, writing and the historical narrative, as a form of organizing the discourse of time. Its teaching presupposes the existence of a community of writing in which the student should be inserted, with the collaboration of the teacher. In other words, for the student to understand the writing of history, he also needs to learn to read and write history, not as a historian, but inserting it in the logic of the rationality of writing in school history.

This is the challenge of the rationality of writing. If writing is presented now as the result of a process of organization of reality which takes Western European society as a reference, this does not mean that there do not exist other forms of organizing this reality, in other words, other forms of being rational and knowing, which even when they are not hegemonic dialogue more or less with the rationality of writing. The intention of universal access to writing through literacy and to the knowledge structured by writing presupposes the universality of the rationality of writing. However, a relevant number of our students, due to their social trajectories before and after school, still do not move around this world of writing in a form appropriate to the continuation of studies in Basic Education. Do they not manage to learn the knowledge of different areas of knowledge because they do not know how to read and write?

This question will not be answered here. However, it is necessary to differentiate what happens within written learning, aiming at the insertion of new learning in the circuit of learning to read and write to learn school knowledge.

Literacy, education and letramento

Tfouni presents the learning of literacy within a controversy: for some it is a process of the individual acquisition of the abilities required for reading and writing; for others it is a process involving the representation of various objects with different natures.

Delineated here is a relationship of literacy with education. For part of learners the references to writing will principally come from the formal education process and from a school network with determined characteristics. Sometimes with absences and limits which will define the relevant differences in the culture of writing with which these learners will relate.

Thos process is not complete at the end of the first classes of Basic Education. However, since literacy is instituted in contemporary societies within the school, it occurs in a more intense or specific form in the early years of Basic Education. At this time, the curriculum and the teachers, in various ways in Brazilian schools, are concerned with teaching writing. Students, according to their trajectories and their forms and conditions of learning and teaching, will appropriate more or less intensely the conditions to read, write and understand through writing.

Reaching the end of Basic Education great changes occur in relation to writing and knowledge. If students are unable to carry out the expected activities, the teacher will organize the work based on the representation of a gap in their knowledge. The history class will be different and the resulting historical knowledge as well. Teachers from various disciplines, including history, when they say they are there to teach their discipline, a common saying in our schools, refuse to teach literacy, since they consider that this is a process which should have been completed when the student reached the current sixth year.

The second half of Basic Education presents specific constrictions for the teacher of disciplines such as history. At this moment, I would like to highlight the conjunction of the time factor (two or three classes a week) with the factor of the extension of the proposed curricular content, which results in the gradual agility of students in relation to writing being counted on. They need to learn history through reading and writing.

Various studies of the history of writing at the end of the twentieth century have highlighted social, historic, linguistic and discursive aspects as being the origin of their possible failure with segments of popular classes that remain on the margin of written culture. As a result, they present the demand of another concept of literacy, which takes into account a broader and more informal process than carried out in the school, through practices and events - before, during and after the learning of written language. This process is called letramento, inspired by the term in English, literacy.

For some specialists, such as Magda Soares, letramento is a condition of those social groups and societies which actually use writing.

Education, letramento and learning to read and write are three processes which overlap and result in different lettered conditions which are modified according to the learning experienced in new practices of reading and writing. Taking into account these affirmations, it is necessary to consider that even a student who is literate to a level adequate for the sixth year may not yet have experienced the specific reading and writing of history texts.

The diverse trajectories of Brazilian school students, which led them to such disparate performance in tests such as Saeb, does not impede them from learning, even with singular approximations with the rationality that is specific of writing. But they raise difficulties for teachers who organizes themselves to teach and make students learn through writing in school time. In this context, when students present characteristics that do not show mastery of writing, they break with the expectations of teacher in their modes of teaching history. It also leads teachers to make didactic choices that respond to their representation about the greater or lesser capacity of these students to learn to write school history.

Beliefs and disbeliefs in the capacity, to read, write and think history

Teacher's representations of the capacity of students to read, write and learn through writing function as a relevant factor in the choice of didactic strategies that will configure the didactic circuit of the class and the history to be taught.

The research from which the examples presented here were obtained was carried out during the school year in history classes in Basic Education. In the research I analyzed the oral and written interaction between teachers and students in the history class in relation to school history knowledge. The research methodology use was inspired by ethnography with intensive field work in two schools, (one public and the other private), in which history classes in Fundamental Education were observed and analyzed under different aspects. Verbal interaction between students and teachers was especially the object of attention, based on the enunciation focus chosen. Writing was registered as close to the form it was registered in, and the words of teachers and students were recorded and transcribed for analysis.

Generally speaking, for the three public school teachers participating in the research, students did not adequately dominate writing and this hindered the work of teaching and learning. For others, although some of the students had learning difficulties related to reading and writing, it was possible to teach and learn history, even asking for reading and writing activities aimed at the construction of knowledge. For private school teachers the problems of learning was located in individual cases, and reading and writing were not considered a problem. To the contrary, they were a necessary condition, meet by students as a whole while carrying out work.

I present below the two didactic choices made by the public school teachers by public school teachers who adopted different positions in their representation of the capacities of students to read, write and know through writing. However, it should be born in mind that this did not involve an evaluation of the content to be taught and learned, since they are canonical content in the Basic Education program.

Belief in an absence: they do not know how to read and write

In the research the teachers who represented their students as not possessing the condition of being lettered emphasized in their classes reading and writing activities, such as oral reading, copying texts and exercises in which fragments of texts copied or read had to be transcribed and read. In other words, writing comes into their classes as support for knowledge that has already been produced, which has to be copied aimed at memorizing it. The teachers justify their choices with the idea of teaching students to read and write, at the same time that they teach history. Another explanation is that, since they have difficulties in understanding history, all that is demanded from them is the task of registering and reproducing, not of establishing relations or other mental activities.

In public school where there is a shortage of school books, the teacher from the sixth grade produced a summary of a school book and wrote it on the blackboard. The transcription of the summary occurred three times during the class. A circuit of activities did not occur, since during various classes the students copied the summary and at the end did an exercise, followed by a text.

The text is characterized by a didactic canonic narrative about the creation of Rome. In addition to the absence of books for the students to work with, the teacher justified the use of the summary as an attempt to adjust the text in accordance with two criteria, facility and extension, adapted to the class time, on the space of the board and the notebook and in the capacity of students to write.

Effectively, when she resumed the text of the book, other transformations occurred, since the interaction between the verbal text, the visual texts, titles, subtitles and complementary texts, which are part of school books, are suppressed.

A text with these characteristics approximate the format of the note made on paper cards by students who learning to read and suppose that the reader is still distant from written culture. Thus, the teacher's investment in a reduced phrasal structure, with repetition of the subject Rome. For her, the criteria of facility presupposes a fifth grade student with a level of comprehension similar to a first grade student.

What does this individual reading of a simplified text, in other words, this interaction of the student only with the summarized text, translate of the concept of history that the teacher presents to and expects from the student? Let us look at the example of one of the question present in the exercise and the test: "In what period was Rome transformed into a city?" In the text the student reads (searches) until he reaches the extract: "It was during the rule of the Etruscan kings that Rome was transformed into a city." In the (non) reading strategy used, the answer is the entire previous extract: "It was during the rule of the Etruscan kings...".

A characteristic of this type of reading control activity is the relationship of complementarity between information. In other words, since information is structured in nominal or verbal phrases with a simplified structure (a simple phrase or composed by coordination), the majority of relations established in questions are between the predecessor and successor in the same phrase without a decontextualized hierarchy between the information. In a relatively short text, as the summary, the task, of answering questions to location information is facilitated. The strategy most used in the reading, with both students with the highest and lowest achievements, is to look for a guiding expression or word as a reference for the phrase which contains the response. Following this, the student will look for the other part of the phrase, which the answer surely is. This strategy was observed in all the classes and grades in public schools (5th-8th), with some variation in use by students more or less competent in reading longer texts.

The use of this reading strategy allows us conclude that this is one the forms of learning offered by school work with reading, including history classes. But this learning did not begin with the fifth grade history class. The student perceives, in the first years of Basic Education, that this strategy 'functions' to answer a certain type of question.

As highlighted by researchers of reading in the early years of Basic Education, this is a strategy which takes place under the auspices of the perception of formal identity among words.

Returning to the example, let us look at the word period present at the beginning of the question: In what period... Even the preparation of this temporal notion, important in the construction of the category of time, is made secondary in this didactic circuit, since it is not necessary for the student to know what it signifies to use the complementary response strategy as one of the terms of affirmation, based on the location of the guiding expression or word.

With the didactic circuit used in this history class, the students may not be learning history and perhaps not even temporal notions, as we have seen. Copied history does not even teach students to read and write. It only teaches them to copy and transcribe, which does not demand that the student think beyond the strategy of filling in the responses, not even to modify the oral or written language.

The concept of reader that this situation indicates is someone who repeats. In other words, the meaning is there and the students' task is to say what is already in the test. This circuit of activities suggests that for the teachers who share this representation, the students are not able to read and write, nor even able to learn history.

Belief in a presence: they know how to read and write

The teacher asked fifth grade students, in the 11 year old age group, during the first weeks of class to produce an essay about their life since birth. The students delivered the essays and during the class the teacher returned them with personal comments. Her intention was to use examples taken from the essays to explain historic sources and landmarks. For this comment, I have highlighted the part of the class that deals with historic sources:

1st part(T01) P: ... This activity is worth 10 points, for the essay telling your life stories, and as well as me knowing a little bit about you through it, I asked you to do this activity to see if you managed... to answer a few things for me. Each of you have your own history, right? Each one is different from the other, your histories will not be the same. However, you can answer some things for me, all of you can answer for me. First, where did you get the information to write about your past?

(T02) A: My mother and father helped me.

(T03) A: I remember the last four years.

(T04) A: My mother helped me.

(T05) P: Your mother and your father? They remember everything? Then let us think of the following: (++) some things you remember, right? Like he said 'I remember the last four years.' Other things your father and mother helped. Let us imagine something: on the day that you did this, your father, mother, uncle, no one was at home and you had amnesia. You did not know anything, you only knew what was written there, to do history homework. You did not remember anything about your lives and had no one around to ask. Do you think you could find something at home that would give you clues about the past?

(T06) A: I looked at photos.

(T07) A: I look at a picture.

(T08) P: What did the photos tell you? No. What type of information could the photo give to you?

(T09) A: What I was like.

(T10) P: When I was small I was fat, I had lots of hair, I was bald, I was much smaller than my brother. The photo could give you this information. What else? [...]

(T14) P: ... Each object that you find, shhhh, pay attention girls! These objects that you find will help you put together this past. Things that were lost in forgetfulness, now you are seeing these objects, you can write about the past...

In the teacher's first speech, among other organizing aspects of the class, (T01) she clarified that each person has a different history, but that the way of having access to this history is similar, in other words, it starts from singular and concrete information to go towards generalization. The two themes explained during the class can be found in the categories of historic source and historic landmark.

The strategy used by the teacher, after getting the essays, is to ask problematizing questions about sources of information about their lives, aiming at establishing a parallel. To the extent that the students will answer and present some alternatives, they continue to problematize, in search of various sources (oral, photographic...). She also seeks to help them perceive that each source allows different information to be known.

Continuation

(T15) ... These objects are called in general, Iank, pay attention, historical sources. (+) What does source mean? I will drink water from the fountain [in Portuguese the same word is used for source and water fountain]. Source is where something is born, from where it leaves. So a historic source is from where history comes. It is these objects that will help us put together this jigsaw puzzle of the past. When the historian is going to write about the life of a people, of a country, he does not have a father, a mother, a grandmother, to tell him what happened. How will he research what happened 400, 500, 600 years ago. What does he have to look for? Objects that are called historic sources will give him the clues, of what this people were like, of what they ate, of what they dressed, where they lived ... so any object left by human beings can be a clue about the past of humanity. Look, I will give you an example. Let us imagine that there was a war and the entire population of Pindorama was exterminated, ok? It is gone, there is no one left. In 300 years an alien spaceship will land here. Aliens will leave the ship wanting to know if there were people here, if it was inhabited, they will not find anyone, but they will begin to find things that are signs that there was intelligent life here.

(T16) A: Great!

(T17) P: So, when they find photos, he mentioned that already, clothes, pieces of clothes, pieces of buildings, of constructions, of bricks...

(T18) A: of buildings...

(T19) A: a pen...

(T20) A: sneakers...

(T21) P: A piece of a table, a chair, sneakers, a backpack. What will this tell them? First, that the region was inhabited, that it had life, because these things are not made in nature. A sneaker tree? A backpack tree? A chair tree? Houses are not born out of the earth, they have to be built, right? People are needed. So all these objects that the extraterrestrials will find, will help him trace more or less what type of people lived here. That these people had iron, plastic, rubber, that they made large buildings to protect themselves, that they covered the body, because sneakers and clothes are used to cover the body. So these objects will help build our image in the head of the ET, what we were like. So what historians do more or less is what these ETs are doing in this story, looking for clues that indicate how a certain people lived, what they thought, how they lived, ok? These things are historic sources. Everything we can find about the human being are historic sources. Do you understand?...

In this part of her talk, she reaches the definition, and for this she uses the present tense and prepares a definition phrase (T15): 'These objects are called in general ... historic sources.' It is interesting to observe her use of the image of the water source/fountain. She does not use this metonymy in a ornamental or merely stylistic manner. To the contrary she seeks in its concreteness the image for the comprehension of the meaning of the term historic source. As Fiorin notes, the figures of language have to be treated as discursive procedures for the creation of meaning.

Her work with oral language, intermingled with writing, uses figurative language which permits movement between the concrete source and the set of ideas that constitute the abstraction historic source. I would like to highlight two things mentioned by the teacher in the first fragment. That of things that were lost in forgetfulness and the mention of the writing of the past, a founding characteristic of history. Mônica maintains a present reference for history and historiographic discourse during her talk: memory, even in its individual dimension, and writing. The teacher prepares an image of the world deliberately exploring the diversity of times. In other words, she proposes that students move through the time of their own lives and afterwards prepares a fantasy narrative in which extraterrestrials in the future arrive to research the school neighborhood (and what exist are ruins of human civilization). Based on this hypothetical example, she deals with the possible distancing of the historian, who needs to work with the ruins of past civilizations.

The teacher uses the production of the text as an object of reflection for this class. As a result, since her aim is for the students to reflect on aspects of the historian's work and history itself, I consider that the text gives value to the process of preparation and the reflection on this process, like a workshop in history.

However, it is not just production. She prepares a discourse with images and analogies which can be understood by students independently of their lettered condition. While continuing with her work, the teacher will make annotations for the students to copy, as well as exercises in which she will require responses that evoke what was constructed and taught, in accordance with the school culture in which her work is inserted. Therefore, a circuit of oral and written activities happens in which the more or less lettered students manage to learn what are historic sources, distant and proximate time, the work of the historian and the analogy between times, as well as other learning.

Some final words

The teachers of the final years in Basic Education highlighted the existence of a problem that directly affects the teaching and learning of history: the absence of mastery of writing by students. As has been seen this problem cannot be ignored due to the risk of the discipline of history becoming ever more decipherable and more distant from the students, especially those in the public teaching network.

Its explanation of the problem points to a precarious learning of how to read and write, as well as cultural baggage which is distant from school expectations. Nevertheless, if we consider that literacy is a process subject to different approaches and in dialogue with the trajectories of insertion in written culture by students, we can see that its results can vary from what is expected by the teachers, requiring didactic approaches that also vary during education. Furthermore, the class cannot only occur in the written form. Preferentially, especially in the grade in which students start to learn history and its characteristic decontextualization, the teacher can prepare activities in which students produce materials with drawings and texts that function and raw material for this didactic circuit and contribute to the plurality of forms of thinking history, with or without writing. A proposal such as this can be understood as reductionist. However, it is not. It is inspired by the practices of teachers who believe their students can continue to learn to read and write, but principally so that they can know and reflect with and through school history.

The consideration that the writing of history, including school history, requires a specific letramento, since reading and writing are always related with a particular type of writing, also shows a potential path for the history teacher, who can also assume their role in the teaching of the written language. Among the alternatives for teaching history closer to the questions related to the teaching of reading, writing and learning, is the consideration of the references of reading theory, which sees all reading as being constituted by meaning, in the dialogue between what is already known and what is not known yet. Therefore, when the teacher is seeking to facilitate a student's understanding of a written text, it is necessary to evoke elements which the students already know to be able to confront the text, in a dialogue between the known and the not yet known. The target is always to know more.

We know that the programmatic content of history extrapolates the time allotted to the class. The teacher, aiming to take into account the program, can establish circuits in which students should read what flows out of the classroom. Nevertheless, especially if the teacher works with classes in which precarious reading and writing condition predominant, something present in the majority of students in our schools, the problem becomes to be less the extent of the content to be taught and more assuming their tasks as a teacher of language, including historic language. Due to its magnitude this problem will still persist for some time, irrespective of our desires as the letters teachers we are. Therefore, the students in our schools, especially those of the public network, can achieve their education in history

NOTES

1 Saeb was created in 1990 as one of a number of governmental initiatives for evaluating school education. It has been held a number of times with a similar format. In 2005 its objectives, as expressed in Edict 931 of Instituto Nacional de Estudos Pedagógicos Anísio Teixeira (Inep), were divided through the creation of the National Evaluation of Primary Education (Avaliação Nacional do Ensino Básico - Aneb), based on by sampling, and which was closer to the initial objectives and methodology of Saeb. Also created was the National Evaluation of School Achievement (Avaliação Nacional do Rendimento no Ensino Escolar - Anresc), with the intention of reaching the full universe of Brazilian schools, known as the Brazil Exam (Prova Brasil). Thos exam intends to show the achievement of students in different schools and municipalities. For more information, see portalideb.inep.gov.br.

2 The current nomenclature corresponding to these grades would be sixth class to ninth class. I have kept the previous one, referring to grades, since the research referred to what occurred the year before the change and to the nomenclature present in the documentation used.

3 As well as Saeb, at that time there also existed the Higher Level Education Test (Provão do Ensino Superior) and Enem.

4 In relation to the former criticism, see GENTILI, Pablo. Neoliberalismo e educação: manual do usuário. In: SILVA, Tomaz Tadeu; GENTILI, Pablo. Escola S.A.: quem ganha e quem perde no mercado educacional brasileiro. Brasília: CNT, 1996. For the latter, see BONAMINO, Alice; COSCARELLI, Carla; FRANCO, Creso. Avaliação e letramento: concepções de letramento subjacentes ao Saeb e ao Pisa. Educação e sociedade, Campinas (SP), v.23, n.81, p.91-113, 2002.

5 The Basic Education Development Index (Índice de Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica - Ideb) brings together two concepts in a single indicator: school flow and performance measures in the evaluations. The indicator is calculated on the basis of data related to school passing rates, obtained in the School Census, and performance measures in Inep, Saeb (for the different states and for the country as a whole) and Prova Brasil (for municipalities). Further information is available at: portalideb.inep.gov.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=45&Itemid=5; accessed on 22 Oct. 2010.

6 See BURKE, Peter. Uma história social do conhecimento de Gutemberg a Diderot. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2003.

7 To understand how this process occurred in European schools, see HILSDORF, Maria Lucia Spedo. O aparecimento da escola Moderna: uma história ilustrada. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2006.

8 See: HAVELLOCK, Eric. A equação oralidade-cultura escrita: uma fórmula para a mente moderna. In: OLSON, David R.; TORRANCE, Nancy. Cultura escrita e oralidade. São Paulo: Ática, 1995. (Coleção Múltiplas Escritas). p.17-34.

9 V. MICHALOWSKI, P. Writing and literacy in early states: a Mesopotamianist perspective. In: KELLER-COHEN, D. (Ed.). Literacy: interdisciplinary conversations. Cresskill (NJ): Hampton Press, 1994, p.49-70 (trad. Cecília Goulart).

10 See ILLICH, Ivan. Um apelo à pesquisa em cultura escrita leiga. In: OLSON; TORRANCE, 1995, cit., p.35-54.

11 See DENNY, Peter. O pensamento racional na cultura oral e a descontextualização da cultura escrita. In: OLSON; TORRANCE, 1995, cit., p.75-100.

12 See the discussion in STREET, B. V. Literacy in theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

13 See CERTEAU, Michel de. A escrita da história. 2.ed. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária, 2000, p.69-103.

14 TFOUNI, Leda V. Letramento e alfabetização. São Paulo: Cortez, 2004. (Coleção Questões da Nossa Época), p.14.

15 See SOARES, Magda. Letramento, um tema em três gêneros. 2.ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2001.

16 See KLEIMAN, Ângela. B. Modelos de letramento e as práticas de alfabetização na escola. In: _____. (Org.). Os significados do letramento. Campinas (SP): Mercado das letras, 1995, p.15-61.

17 I refer to representations, considering especially one of the modalities related to the social world proposed by Roger Chartier: "the work of classification and selecting which produces multiple intellectual configuration through which reality is contradictorily constructed by different groups that compose a society." CHARTIER, Roger. O mundo como representação. Estudos Avançados, São Paulo: USP, v.5, n.11, p.183-191, 1991.

18 An evaluation of teaching books as reading material lies outside the scope of this text. In another publication, I analyze the correlations between the text of the summary and the text on which it is based.

19 See BATISTA, Antonio A. G. O ensino de Português e sua investigação: quatro estudos exploratórios. Doctoral Dissertation (Doctorate in Education) - PPGFE/UFMG. Belo Horizonte, 1996.

20 See KLEIMAN, Ângela. Aprendendo palavras, fazendo sentido: o ensino de vocabulário nas primeiras séries. In: TASCA, Maria (Org.). Desenvolvendo a língua falada e escrita. Porto Alegre: Sagra, 1990, p.9-48.

21 The codification indicates T for the order of speaking, P: teacher A: student, the interlocutors.

22 See FIORIN, José L. Teorias do discurso e ensino da leitura e da redação. Gragoatá, Niterói, n.2, p.7-27, 1º sem. 1997.

23 See RODRIGUES; SILVA, Vitória. Estratégias de leitura e competência leitora: contribuições para a prática de ensino em História. História, Franca (SP), v.23, n.1-2, p.69-83, 2004.

24 See RÜSEN, Jörn. O que é formação histórica. In: _____. História viva: teoria da história: formas e funções do conhecimento histórico. Trad. Estevão de Rezende Martins. Brasília: Ed. UnB, 2007, p.95-103.

Article received in October 2010.

Approved in December 2010.

- 4 Em relação à primeira crítica, ver GENTILI, Pablo. Neoliberalismo e educação: manual do usuário. In: SILVA, Tomaz Tadeu; GENTILI, Pablo. Escola S.A.: quem ganha e quem perde no mercado educacional brasileiro. Brasília: CNT, 1996.

- Quanto à segunda, ver BONAMINO, Alice; COSCARELLI, Carla; FRANCO, Creso. Avaliação e letramento: concepções de letramento subjacentes ao Saeb e ao Pisa. Educação e sociedade, Campinas (SP), v.23, n.81, p.91-113, 2002.

- 6 Ver BURKE, Peter. Uma história social do conhecimento de Gutemberg a Diderot Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2003.

- 7 Para conhecer como esse processo se deu nas escolas europeias, ver HILSDORF, Maria Lucia Spedo. O aparecimento da escola Moderna: uma história ilustrada. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2006.

- 8 Ver HAVELLOCK, Eric. A equação oralidade-cultura escrita: uma fórmula para a mente moderna. In: OLSON, David R.; TORRANCE, Nancy. Cultura escrita e oralidade São Paulo: Ática, 1995. (Coleção Múltiplas Escritas). p.17-34.

- 9 V. MICHALOWSKI, P. Writing and literacy in early states: a Mesopotamianist perspective. In: KELLER-COHEN, D. (Ed.). Literacy: interdisciplinary conversations. Cresskill (NJ): Hampton Press, 1994, p.49-70 (trad. Cecília Goulart).

- 10 Ver ILLICH, Ivan. Um apelo à pesquisa em cultura escrita leiga. In: OLSON; TORRANCE, 1995, cit., p.35-54.

- 11 Ver DENNY, Peter. O pensamento racional na cultura oral e a descontextualização da cultura escrita. In: OLSON; TORRANCE, 1995, cit., p.75-100.

- 12 Ver discussão em STREET, B. V. Literacy in theory and practice Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- 13 Ver CERTEAU, Michel de. A escrita da história 2.ed. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária, 2000, p.69-103.

- 14 TFOUNI, Leda V. Letramento e alfabetização São Paulo: Cortez, 2004. (Coleção Questões da Nossa Época), p.14.

- 15 Ver SOARES, Magda. Letramento, um tema em três gêneros 2.ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2001.

- 16 Ver KLEIMAN, Ângela. B. Modelos de letramento e as práticas de alfabetização na escola. In: _______. (Org.). Os significados do letramento Campinas (SP): Mercado das letras, 1995, p.15-61.

- 17 Refiro-me a representações considerando em especial uma das modalidades de relação com o mundo social propostas por Roger Chartier: "o trabalho de classificação e de recorte que produz configurações intelectuais múltiplas pelas quais a realidade é contraditoriamente construída pelos diferentes grupos que compõem uma sociedade". CHARTIER, Roger. O mundo como representação. Estudos Avançados, São Paulo: USP, v.5, n.11, p.183191, 1991.

- 19 Ver BATISTA, Antonio A. G. O ensino de Português e sua investigação: quatro estudos exploratórios. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) PPGFE/UFMG. Belo Horizonte, 1996.

- 20 Ver KLEIMAN, Ângela. Aprendendo palavras, fazendo sentido: o ensino de vocabulário nas primeiras séries. In: TASCA, Maria (Org.). Desenvolvendo a língua falada e escrita Porto Alegre: Sagra, 1990, p.9-48.

- 22 Ver FIORIN, José L. Teorias do discurso e ensino da leitura e da redação. Gragoatá, Niterói, n.2, p.7-27, 1ş sem. 1997.

- 23 Ver RODRIGUES; SILVA, Vitória. Estratégias de leitura e competência leitora: contribuições para a prática de ensino em História. História, Franca (SP), v.23, n.1-2, p.69-83, 2004.

- 24 Ver RÜSEN, Jörn. O que é formação histórica. In: _______. História viva: teoria da história: formas e funções do conhecimento histórico. Trad. Estevão de Rezende Martins. Brasília: Ed. UnB, 2007, p.95-103.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

26 May 2011 -

Date of issue

2010

History

-

Accepted

Dec 2010 -

Received

Oct 2010