Abstract

Black-necked swans are distributed across South America and face conservation problems in Chile according to data of the State institution SAG. The aim of this study was to identify helminths and to assess associated tissue damage via histopathology. A total of 19,291 parasites were isolated from 21 examined birds; 17 species were identified, including nematodes, flukes, and tapeworms. Of these, 12 were new host records, 13 were reported for the first time in Chile, and 5 were new records for the Neotropical region. Further, the flukes Schistosomatidae gen. sp. and Echinostoma echinatum are of zoonotic concern. Regarding histopathology, an inflammatory response was found along the birds’ entire digestive tract. Nevertheless, it is difficult to declare that there is a clear association between such lesions and isolated parasites, as other noxa could be responsible as well. Although in some cases there was an evident association, such inflammatory responses and necrosis were minimal, as occurred with Capillaria, Retinometra, Catatropis, Echinostoma, and Schistosomatidae gen. sp. Nevertheless, Epomidiostomum vogelsangi caused granulomatous injuries, an important inflammatory response, and necrosis, but it always circumscribed to superficial layers of the gizzard. Conversely, Paramonostomum was not associated with an inflammatory response despite a high parasitic load.

Keywords:

Cygnus melancoryphus; helminths; histopathology; zoonoses; Chile

Resumo

O cisne de pescoço negro é distribuído por toda a América do Sul, e enfrenta problemas de conservação no Chile, sendo protegido pela Lei Estadual de Caça. O objetivo deste estudo foi identificar helmintos em cisnes e avaliar o dano tecidual por meio de histopatologia. Um total de 19.291 parasitas foi isolado de 21 aves examinadas, sendo 17 espécies identificadas, entre nematóides, trematódeos e tênias. Destes, 12 são novos registros de hospedeiros, 13 são reportados pela primeira vez no Chile, e 5 são novos registros para a região Neotropical. Além disso, os trematódeos Schistosomatidae gen. sp. e Echinostoma echinatum detectados têm importância zoonótica. Em relação à histopatologia, uma resposta inflamatória foi encontrada em todo o trato digestivo. Entretanto, é difícil estabelecer uma associação estrita de tais lesões com parasitas isolados, porque outros fatores também poderiam ser responsáveis. Em alguns casos, houve uma associação óbvia entre parasitas e lesões, embora a resposta inflamatória e a necrose fossem mínimas, como foi o caso dos gêneros Capillaria, Retinometra, Catatropis, Echinostoma e Schistosomatidae gen. sp. Entretanto, Epomidiostomum vogelsangi causou lesões granulomatosas com importante resposta inflamatória e necrose, mas sempre circunscrita às camadas superficiais da moela. Por outro lado, Paramonostomum não foi associado com uma resposta inflamatória óbvia apesar da alta carga parasitária.

Palavras-chave:

Cygnus melancoryphus; helmintos; histopatologia; zoonoses; Chile

Introduction

Parasitism is a trophic association between individuals of two different species where at least one of them (the parasite) feeds off another species (the host). Avian hosts serve as habitats that provide resources to parasites; meanwhile, the host is damaged or potentially loses some of its nutritional resources and has to develop an immune response against the parasite, which is costly. Furthermore, the host must repair or replace damaged tissues and may also experience impaired development. Yet, the costs of parasitism are not always evident for most avian species, as the host can tolerate the presence of parasites; otherwise, diseases associated with parasitism could be overshadowed by predation of sick individuals. Parasitism by helminths is common between wild birds, as they are affected by a great variety of parasites throughout their lifespan; however, there are still unknown features of certain species, particularly related to some biological or pathological aspects (WOBESER, 2008Wobeser G. Parasitism: Costs and Effects. In: Atkinson C, Thomas N, Hunter D. Parasitic Diseases of Wild Birds. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 3-9.).

In Chile, there are two species of swans – the Coscoroba swan Coscoroba coscoroba Molina, 1782 and the black-necked swan Cygnus melancoryphus Molina, 1782 (Anatidae) – both of which are distributed along South America (JOHNSGARD, 2010Johnsgard P. Ducks, geese, and swans of the world. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press; 2010.). Currently, C. melancoryphus is considered as a least concern species (BIRDLIFE INTERNATIONAL, 2016BirdLife International. Cygnus melancoryphus [online]. Cambridge: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; 2016 [cited 2016 June 24]. Available from http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22679846A92832118.en

http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3...

), however, according to local data provided by the State institution Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero (SAG), this swan has conservancy issues along its Southern distribution in Chile (CHILE, 2018Chile. Ministerio de Agricultura. Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero. Ley N°19.473 y su Reglamento. Chile: Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero, Gobierno de Chile; 2018.).

There is scarce knowledge regarding the endoparasites that affect waterfowl from Chile, with only three species studied to date; Anas georgica Gmelin, 1789, Chloephaga picta Gmelin, 1789 and C. melancoryphus (SCHLATTER et al., 1991Schlatter RP, Salazar J, Villa A, Meza J. Reproductive biology of black-necked swans Cygnus melancoryphus at three Chilean wetland areas and feeding ecology at Rio Cruces. Wildfowl 1991;(Suppl. 1): 268-271.; GONZÁLEZ et al., 2005González D, Skewes O, Candia C, Palma R, Moreno L. Estudio del parasitismo gastrointestinal y externo en caiquén Chloephaga picta Gmelin, 1789 (Aves, Anatidae) en la región de Magallanes, Chile. Parasitol Latinoam 2005; 60(1-2): 86-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-77122005000100016.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-77122005...

; DRAGO et al., 2007Drago FB, Lunaschi LI, Hinojosa-Saez AC, González-Acuña D. First record of Australapatemon burti and Paramonostomum pseudalveatum (Digenea) from Anas georgica (Aves, Anseriformes) in Chile. Acta Parasitol 2007; 52(3): 201-205. http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11686-007-0040-1.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11686-007-004...

; HINOJOSA-SÁEZ et al., 2009Hinojosa-Sáez A, González-Acuña D, George-Nascimento M. Parásitos metazoos de Anas georgica Gmelin, 1789 (Aves: Anseriformes) en Chile central: especificidad, prevalencia y variaciones entre localidades. Rev Chil Hist Nat 2009; 82(3): 337-345. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0716-078X2009000300002.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0716-078X2009...

; GONZÁLEZ-ACUÑA et al., 2010González-Acuña D, Moreno L, Cicchino A, Mironov S, Kinsella M. Checklist of the parasites of the black-necked swan, Cygnus melanocoryphus (Aves: Anatidae), with new records from Chile. Zootaxa 2010; 2637(1): 55-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637.1.3.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637....

; VALENZUELA et al., 2018Valenzuela G, Araya A, Oyarzún-Ruiz P, Muñoz P. Helminth fauna of the black-necked swan Cygnus melancoryphus (Aves: Anatidae) from Carlos Anwandter Nature Sanctuary, Valdivia, Chile. Rev Mex Biodivers 2018; 89(2): 568-571. http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2018.2.2323.

http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e....

). However, none of these studies contemplated adopting a histopathological approach related to parasites. According to Agüero et al. (2016)Agüero ML, Gilardoni C, Cremonte F, Diaz JI. Stomach nematodes of three sympatric species of anatid birds off the coast of Patagonia. J Helminthol 2016; 90(6): 663-667. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X15000899. PMid:26522056.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X15000...

, in the Neotropical region, the panoramic landscape is very similar, with waterfowl being the less frequently studied group of birds in terms of parasitic fauna. Consequently, it is indispensable to report the presence and describe the histopathological changes caused by parasites, which could be the consequence of a normal response or an impairment of the homeostatic mechanisms of the host (WOBESER, 2008Wobeser G. Parasitism: Costs and Effects. In: Atkinson C, Thomas N, Hunter D. Parasitic Diseases of Wild Birds. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 3-9.). Thus, the aims of the present study were to contribute additional records to the helminth fauna of C. melancoryphus and to establish the potential pathological consequences of gastrointestinal parasitism.

Materials and Methods

Necropsy

Under the supervision of the state agency CONAF, a total of 21 carcasses of C. melancoryphus (9 females [8 immatures and 1 adult] and 12 males [10 immatures and 2 adults]) were collected from the wetland Carlos Anwandter Nature Sanctuary, Los Ríos region, Chile (39°41’15”S; 73°11’31”O) between July 2014 and September 2015. The birds were carried to Unidad de Anatomía Patológica, Universidad Austral de Chile, where necropsy was performed. The sex and age of the birds were recorded by examining the gonads and plumage of each bird, respectively. Also the body condition was stated for every bird, with scores between 1, as an emaciated bird, and 5 as excellent body condition according to Brown (1996)Brown ME. Assessing body condition in birds. In: Nolan V Jr, Ketterson ED. Current ornithology. Indiana: Springer Science+Business Media; 1996. p. 67-135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-5881-1_3.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-588...

.

Parasitological examination

Every section of the gastrointestinal tract, including the bursa of Fabricius, was carefully examined under stereomicroscope with 35× magnification. The keratinized koilin lining of the gizzard was removed to look for parasites beneath it; meanwhile, the muscle wall was cut into thin layers for the same purpose. All isolated parasites were fixed and preserved in 70% ethanol. Nematodes were mounted between a glass slide and coverslip with Aman’s lactophenol for at least 24 hours to achieve diaphanization. For tapeworms and flukes, these were dehydrated in different concentrations of ethanol, stained with Semichon’s acetocarmine, and mounted with Canada balsam. All helminths were measured and photographed with the aid of the ScopeImage v9.0 software package (SudeLab 2009) and LAS EZ, which was associated with a light microscope (SudeLab) and stereomicroscope (LEICA EZ4HD), respectively. Helminths were identified following the descriptions of Travassos (1915)Travassos L. Contribuições para o conhecimento da fauna helmintolojica brasileira. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1915; 7(2): 146-172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761915000200002.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761915...

, Seurat (1918)Seurat LG. Sur les Strongles du gésier des palmipèdes. Bull Mus Natl Hist Nat 1918; 24: 345-351., Cram (1927)Cram EB. Bird parasites of the nematode suborders Strongylata, Ascaridata and Spirurata. Washington: Smithsonian Institution United States National Museum; 1927. (Bulletin 140). http://dx.doi.org/10.5479/si.03629236.140.1.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5479/si.03629236.14...

, Wetzel (1931)Wetzel R. Description of a new species of Amidostomine worm of the genus Epomidiostomum from the gizzard of anserine birds. Proc U S Natl Mus 1931; 78(2864): 2-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.5479/si.00963801.78-2864.1.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5479/si.00963801.78...

, Freitas & Mendonça (1949)Freitas JFT, Mendonça JM. Novo tricostrongilídeo parasito de “Chauna torquata” (Oken) (Nematoda). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1949; 47(1-2): 27-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761949000100002.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761949...

, Beverley-Burton (1958)Beverley-Burton M. A new notocotylid trematode, Uniserialis gippyensis gen. et sp. nov., from the mallard, Anas platyrhyncha platyrhyncha L. J Parasitol 1958; 44(4): 412-415. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3274325. PMid:13564355.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3274325...

, Pfeiffer (1960)Pfeiffer H. Hymenosphenacanthus bulbocirrosus spec. nov. (Hymenolepididae), ein neuer bandwurm des schwarzhalsschwanes. Z Parasitenkd 1960; 20(4): 345-349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00261223. PMid:13735165.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00261223...

, Wakelin (1963)Wakelin D. Capillaria obsignata Madsen, 1945 (Nematoda) from the black swan. J Helminthol 1963; 37(4): 381-386. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X00019982.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X00019...

, Stunkard (1967aStunkard HW. The morphology, life-history, and systematic relations of the digenetic trematode, Uniserialis breviserialis sp. nov., (Notocotylidae), a parasite of the bursa fabricius of birds. Biol Bull 1967a; 132(2): 266-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1539894. PMid:29332442.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1539894...

, bStunkard HW. Studies on the trematode genus Paramonostomum Lühe, 1909 (Digenea: notocotylidae). Biol Bull 1967b; 132(1): 133-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1539883. PMid:6040022.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1539883...

), Travassos et al. (1969)Travassos L, Freitas JFT, Kohn A. Trematódeos do Brasil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1969; 67(1): 1-886. PMid:5397756., Bisset (1977)Bisset S. Notocotylus tadornae n. sp. and Notocotylus gippyensis (Beverley-Burton, 1958) (Trematoda: Notocotylidae) from waterfowl in New Zealand: morphology, life history and systematic relations. J Helminthol 1977; 51(4): 365-372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X00007720.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X00007...

, Boero et al. (1972)Boero JJ, Led JE, Brandetti E. Algunos parásitos de la avifauna argentina. Analecta Vet 1972; 4(1): 17-34., McDonald (1981)McDonald M. Key to trematodes reported in waterfowl. Washington: Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of the Interior; 1981. (Resource publication; 142)., Anderson et al. (1989)Anderson R, Chabaud A, Willmott S. CIH keys to the nematode parasites of vertebrates. Wallingford: CAB International Institute of Parasitology; 1989., Czaplinski & Vaucher (1994)Czaplinski B, Vaucher C. Family Hymenolepididae Ariola, 1899. In: Khalil LF, Bray RA. Keys to the cestode parasites of vertebrates. Wallingford: CAB International; 1994. p.595-664., Vicente et al. (1995)Vicente JJ, Rodrigues HO, Gomes DC, Pinto RM. Nematóides do Brasil. Parte IV: nematóides de aves. Rev Bras Zool 1995; 12(Suppl. 1): 1-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81751995000500001.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81751995...

, Evans et al. (1997)Evans DW, Irwin SWB, Fitzpatrick SM. Metacercarial encystment and in vivo cultivation of Cercaria lebouri Stunkard 1932 (Digenea: Notocotylidae) to adults identified as Paramonostomum chabaudi van Strydonck 1965. Int J Parasitol 1997; 27(11): 1299-1304. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7519(97)00102-1. PMid:9421714.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7519(97)...

, Flores & Brugni (2003)Flores V, Brugni N. Catatropis chilinae n. sp. (Digenea: Notocotylidae) from Chilina dombeiana (Gastropoda: Pulmonata) and notes on its life-cycle in Patagonia, Argentina. Syst Parasitol 2003; 54(2): 89-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1022593810479. PMid:12652062.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:102259381047...

, Jones et al. (2005)Jones A, Bray RA, Gibson DI. Keys to the Trematoda: volume 2. London: CABI Publishing and The Natural History Musem; 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/9780851995878.0000.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/9780851995878....

, Kostadinova (2005)Kostadinova A. Family Echinostomatidae Looss, 1899. In: Jones A, Bray R, Gibson D. Keys to the Trematoda: volume 2. London: CABI Publishing; 2005. p. 9-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/9780851995878.0009.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/9780851995878....

, Durette-Desset (2009)Durette-Desset MC. Strongylida, Trichostrongyloidea. In: Anderson R, Chabaud A, Willmot S. Keys to the nematode parasites of vertebrates: archival volume. London: CABI International; 2009. p. 110-177. http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/9781845935726.0110.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/9781845935726....

, and Tamaru et al. (2015)Tamaru M, Yamaki S, Jimenez LA, Sato H. Morphological and molecular genetic characterization of three Capillaria spp. (Capillaria anatis, Capillaria pudendotecta, and Capillaria madseni) and Baruscapillaria obsignata (Nematoda: Trichuridae: Capillariinae) in avians. Parasitol Res 2015; 114(11): 4011-4022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-015-4629-2. PMid:26204803.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-015-462...

. Parasitological descriptors, including prevalence (P), intensity (I), mean intensity (MI), mean abundance (MA), and range (R), were calculated and interpreted according to Bush et al. (1997)Bush AO, Lafferty KD, Lotz JM, Shostak AW. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: margolis et al. revisited. J Parasitol 1997; 83(4): 575-583. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3284227. PMid:9267395.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3284227...

. All isolated parasites were deposited in the collection at the Unidad de Parasitología Veterinaria, Universidad Austral de Chile (1164-1184Parasitol.UACh).

Histopathological examination

A sample of each segment of the gastrointestinal tract, including the esophagus, proventriculus, gizzard, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon, and caeca, was cut, deposited, and fixed in buffered 10% formalin for further histopathological examination. The samples were dehydrated in a rotary tissue processor (Histokinette®, Columbia Industrial Developments Limited) and embedded in solid paraffin (Histosec®); with the aid of a microtome, sections of 5 μm in thickness were obtained and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The histopathological sections were observed under light microscope (Olympus CX21). Every inflammatory response was characterized, and the percentage of presentation was expressed in parentheses. Photographs were taken using the MicrometrixTM SE Premium v.2.8 software associated to the light microscope. Samples suspected of fibrosis and with the presence of hemosiderin were stained with Van Gieson’s stain and Prussian blue stain, respectively, for confirmation.

Results

Parasitological findings

A total of 19,291 helminths were isolated; all birds were parasitized by at least 1 parasite species. From all parasites collected, 60.4% were tapeworms (n=11,650), 25.4% were flukes (n=4,905), and 14.2% were nematodes (n=2,736). For the phylum Nematoda, the following species were identified: Epomidiostomum vogelsangi Travassos, 1937 (Amidostomatidae); Paramidostomum pulchrum Freitas & Mendonça, 1949 (Dromaeostrongylidae); Baruscapillaria obsignata (Madsen, 1945) Moravec, 1982; Capillaria pudendotecta Lubimova 1947 (Trichuridae); and Tetrameres (Petrowimeres) fissipina Diesing, 1861 (Tetrameridae). In the case of Platyhelminthes, class Digenea, the following species were recorded: Catatropis chilinae Flores & Brugni, 2003; Notocotylus attenuatus (Rudolphi, 1809) Kossack, 1911; Notocotylus breviserialis Stunkard, 1967; Paramonostomum alveatum Mehlis in Creplin, 1846; Paramonostomum chabaudi Van Strydonck, 1965; Uniserialis gippyensis Beverley-Burton, 1958; Uniserialis tadornae Bisset, 1977 (Notocotylidae); Echinostoma echinatum Zeder, 1803; Echinostoma mendax Dietz, 1909 (Echinostomatidae); and Schistosomatidae gen. sp. Meanwhile, for the class Cestoda, only two species were recorded: Retinometra cf. bulbocirrosus Pfeiffer, 1960; and Sobolevicanthus sp. (Hymenolepididae) (Figures 1-9). The most prevalent parasite was E. vogelsangi (P= 100%), while the parasites that were less frequently present were P. pulchrum (P= 4.8%) and T. (P.) fissipina (P= 4.8%). Regarding mean intensity and mean abundance, R. cf. bulbocirrosus was the species with the highest level of infection per bird. For details about the parasitological parameters for every species, see Table 1. The highest parasitic load found was 3,403 parasites in one swan; on the contrary, the lowest load was 96 parasites. Co-infections between different species of the same genus were recorded for N. attenuatus/N. breviserialis (4.8%), P. alveatum/P. chabaudi (14.3%), and E. echinatum/E. mendax (14.3%). Also, coinfections between species of the same family were recorded for Trichuridae (52.4%), Notocotylidae (47.6%), Echinostomatidae (14.3%), and Hymenolepididae (23.8%).

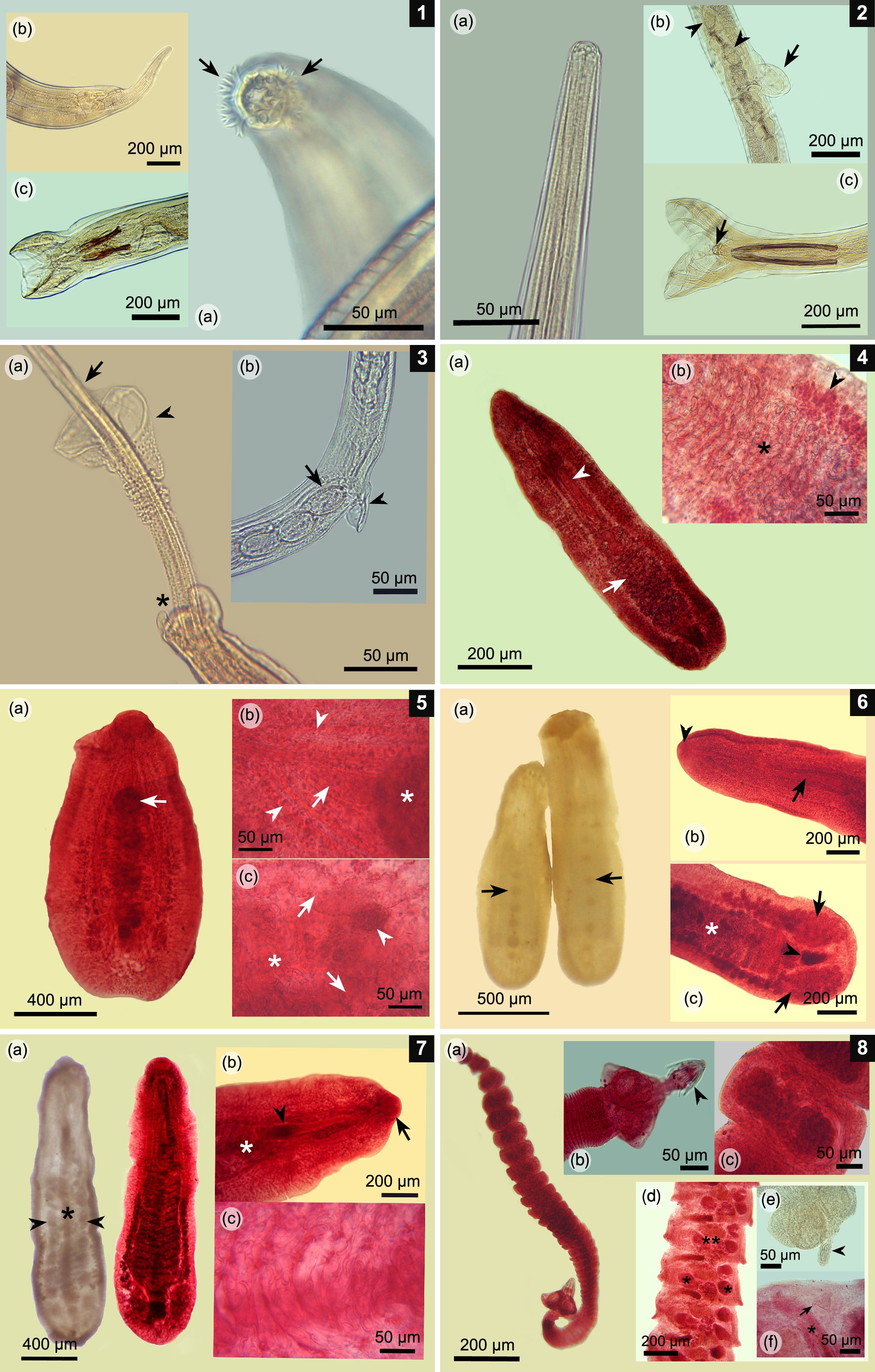

(1a-c) Epomidiostomum vogelsangi. (a) Anterior end with cephalic epaulet surrounding the buccal aperture (arrows); (b) Posterior end of the female with its finger-shaped tail; (c) Male worm; copulatory bursa and two spicules bifurcated at its caudal tip. (2a-c) Paramidostomum pulchrum. (a) Anterior end with no ornamentation and wide buccal aperture; (b) Vulvar area with a vulvar appendix (arrow) and some eggs inside uterus (arrowheads); (c) Male worm; copulatory bursa with a pair of long spicules and gubernaculum (arrow). (3a-b) Capillaria pudendotecta. (a) Posterior end of the male worm with a pair of tubercles (asterisk), single spicule (arrow) and spicule sheath covered on its surface with small spines, except on its caudal portion (arrowhead); (b) Vulvar area with a small vulvar appendix (arrowhead) and typical capillarid-like eggs, which are rough on its surface (arrow). (4a-b) Paramonostomum chabaudi. (a) Ovigerous specimen in toto; note lanceolate body, a long cirrus sac (arrowhead), and uterus located in the caudal third of the body (arrow). (b) Uterine loops crowded with typical notocotylid-like eggs (asterisk) and lateral vitellaria (arrowhead). (5a-c) Uniserialis gippyensis. (a) Parasite in toto; note the single central row of ventral papillae (arrow); (b) Forebody; short cirrus sac (arrow) cranial to the first ventral papilla (asterisk) and lateral intestinal caeca (arrow heads); (c) Posterior third of the body; uterine loops with several eggs (asterisk), lateral caeca (arrows), and small central ovary (arrowhead). (6a-c) Uniserialis tadornae. (a) Fluke in toto with its single ventral row of papillae (arrows); (b) Forebody; note the long cirrus sac (arrow) and single oral sucker (arrowhead); (c) Hindbody; note the ovigerous uterine loops (asterisk), a pair of laterally lobulated testes (arrows), and a central lobulated ovary (arrowhead). (7a-c) Catatropis chilinae. (a) Fluke in toto; one without staining, with its characteristic single central ridge (asterisk) and lateral rows of papillae (arrowheads) (left); the other one is stained (right); (b) Forebody with its only oral sucker (arrow), cirrus sac (arrowhead), and first uterine loops (asterisk); (c) Uterine loops full of notocotylid-like eggs. (8a-c) Retinometra cf. bulbocirrosus. (a) Mature tapeworm in toto; note its small size; (b) Scolex armed with four triangular suckers and a rostellum with small hooks (arrowhead); (c) Ovigerous proglottids crowded with small eggs. (8d-f) Sobolevicanthus sp. (d) Mature proglottids testes (asterisks), 1 lobulated ovary (double asterisk), cirrus sac, and genital atrium; (e) Scolex armed with four rounded suckers and a retracted rostellum (arrowhead); (f) Close-up of the mature proglottid characterized by a conical accessory sac (arrow), feature typical for this genus. Note the genital atrium and cirrus (asterisk).

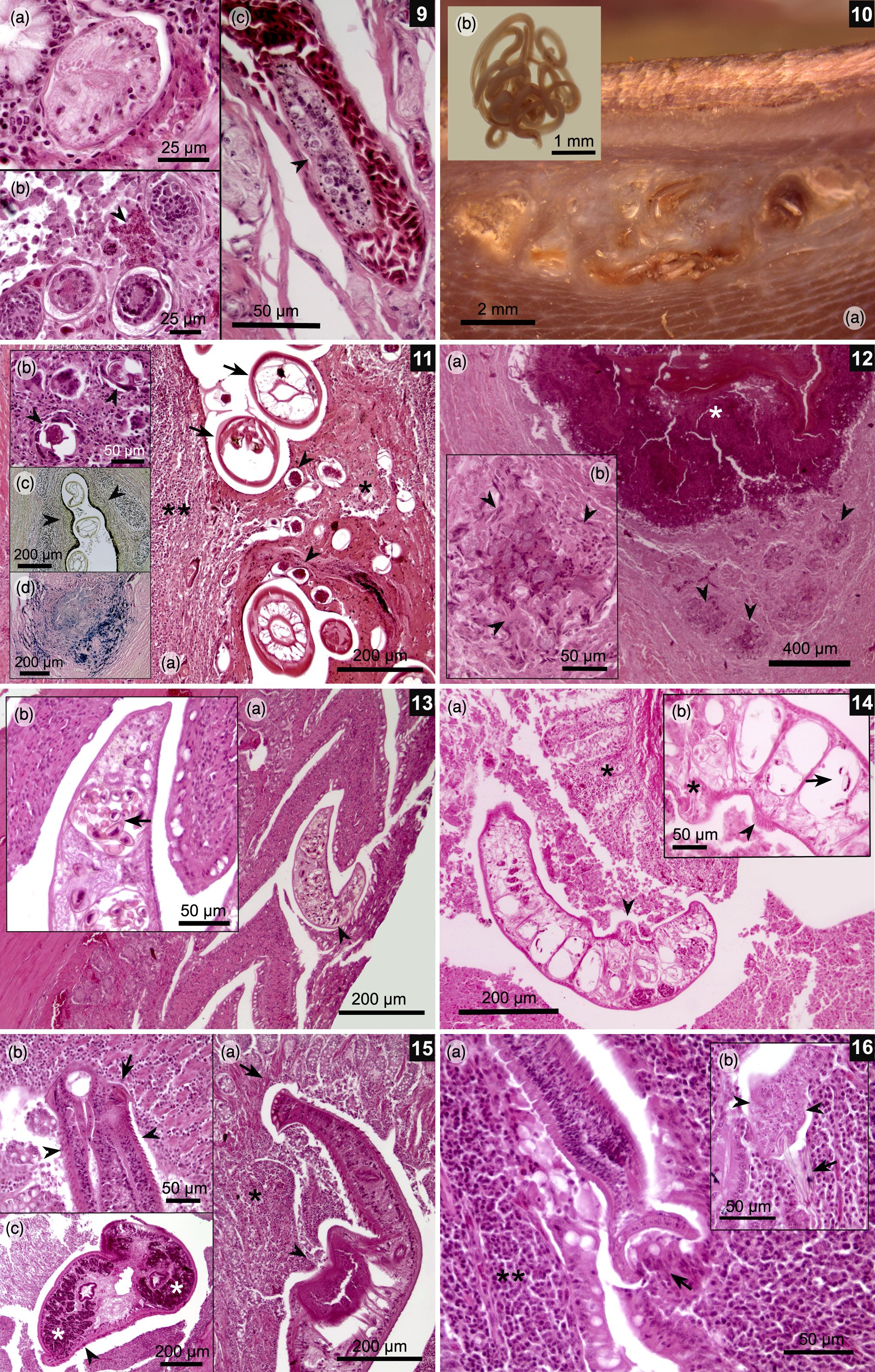

(9a-c) Schistosomatidae gen. sp. (a) Transverse section of the fluke inside a small blood vessel in the cecal mucosa; (b) Different development stages of embryonated eggs associated with a local heterophile response in the colonic mucosa (arrowhead); (c) A section of fluke inside a blood vessel (arrowhead) in the colonic muscle wall. (10-12) Gizzard muscle wall. (10a) Macroscopic lesions in gizzard pads caused by multiple nematodes (10b). (11a) Granulomatous lesions associated to multiple nematode sections (arrows) and strongyle-like eggs (arrow heads) surrounded by necrotic tissue (asterisk) and lymphocytic infiltration (double asterisk). (11b) Giant cells surrounding and destroying strongyle-like eggs (arrowheads). (11c) Van Gieson’s stain showing orange-colored collagen strips around parasitic granulomas (arrowheads), indicating lesion chronicity. (11d) Prussian blue stain, showing presence of iron (blue) associated with macrophages, which is a consequence of old hemorrhages. (12a) A Splendore–Hoeppli lesion characterized by amorphous eosinophilic tissue (asterisk) surrounded by bacterial colonies (arrowheads). (12b) Close-up of bacterial colonies bordered by multiple giant cells (arrowheads). (13a-b) Jejunum. (a) A Paramonostomum-like fluke between villi with no evident inflammatory response; (b) Close-up of a fluke showing its uterus filled with notocotylid-like eggs with a pair of polar filaments (arrow). (14a-b) Caeca. (a) A Catatropis-like fluke folded over mucosa (arrowhead) with a mild inflammatory response (asterisk); (b) Parasitic uterus filled with typical notocotylid-like eggs (arrow); also note the presence of a ventral central ridge (asterisk) and lateral papillae (arrowhead), which are characteristic for this genus. (15a-c) A Echinostoma mendax-like fluke. (a) Larval echinostome fluke located between colonic villi; note erosion of the mucosa due to the action of a circumoral head-collar (arrow) and acetabulum (arrowhead), which is associated with an inflammatory response (asterisk); (b) Circumoral head-collar embedded in the colonic mucosa with its characteristic collar spines (arrow) and body spines (arrowheads). There is an evident immune response; (c) Transverse section of the fluke over the cecal mucosa with a lymphocyte response. Note the vitellaria in the periphery of the body fluke (asterisks) and small body spines (arrowhead). (16a-b) Duodenum. (a) Small tapeworm with one of its suckers over the epithelium of villi (arrow); also, lymphocyte infiltration in the mucosa is evident (double asterisk); (b) A Retinometra cf. bulbocirrosus-like tapeworm located between villi near the Lieberkühn glands. Note the small skrjabinoid hooks (arrow) and triangular suckers (arrowheads) typical for this parasite.

Parasitological parameters and organs of isolation of the recorded parasites for the black-necked swan (Cygnus melancoryphus) from the Carlos Anwandter Nature Sanctuary, Ramsar site, Los Ríos region, Chile.

Epomidiostomum vogelsangi was found mostly in the muscle wall of the gizzard (61.9%), followed by beneath the koilin layer of the gizzard pads (37.9%). Meanwhile, P. pulchrum was isolated only in the latter site. Baruscapillaria obsignata and C. pudendotecta were isolated mostly from the colon (73.2%) and caeca (91.8%), respectively. Tetrameres (P.) fissipina was isolated from the mucosal layer of the proventriculus. Caeca were the preferred organ for C. chilinae and N. attenuatus (99.6% and 82.5%, respectively), P. chabaudi (100%), and U. tadornae (100%). Meanwhile, N. breviserialis and U. gippyensis were isolated from the bursa of Fabricius (80% and 100%, respectively), while P. alveatum preferred the jejunum (52.8%) followed by the ileum (40.8%). Echinostoma echinatum and E. mendax were recorded mostly from the colon (75% and 72.8%, respectively). For tapeworms, R. cf. bulbocirrosus was isolated mostly from the duodenum (87.2%), while Sobolevicanthus sp. was found in the jejunum (88.9%).

Pathological findings

Most of granulomatous lesions caused by E. vogelsangi were observed in the muscle wall immediately under the koilin layer of the gizzard pads (80%), with no additional lesions found in the deeper layers. Also, 16.7% of gizzard pads showed evidence of necrosis and detachment of the koilin layer, as they presented a clay color with multiple nematodes. Microscopically, several worms had peripherally displaced the muscle fibers, also they were surrounded by necrotic tissue mixed with strongyle eggs. Furthermore, moderate fibrosis was evident around this area, which was confirmed through Van Gieson’s stain. The inflammatory response was mixed and multifocal to diffuse, characterized by severe and mild infiltration of the lymphocytes (66.7%) and heterophiles (33.3%), respectively. Further, there was mild infiltration of the macrophages (38.9%), with hemosiderin granules, as confirmed by Prussian blue stain. Similarly, also evident was moderate infiltration of giant cells (44.4%) surrounding the strongyle eggs and small areas of mineralization (16.7%) (Figures 10a, b and 11a-d). In one swan, a Splendore-Hoeppli lesion was evident in the muscle wall, which contained multiple bacterial colonies that were surrounded by eosinophilic amorphous tissue and giant cells (Figures 12a, b). In the area between gizzard pads, strongyle eggs and worms were found embedded in the koilin layer, displacing the glandular tissue; this was associated with a mixed inflammatory response. Severe infiltration of lymphocytes (41.7%), heterophiles and macrophages (25%), traces of hemorrhage (16.7%), hemosiderin granules (8.3%), and bacterial colonies (16.7%) were also observed.

At histopathology, capillarid nematodes were observed free in the colonic lumen. Meanwhile, others were coiled beneath the cecal epithelium with minimal inflammatory response; they were surrounded by mild lymphocyte infiltration. In both organs, capillarid eggs were observed free in the lumen.

No parasites were recorded in the histopathological sections of the proventriculus; however, there was a mixed inflammatory response, characterized by moderate infiltration of the lymphocytes (44.4%), and macrophages with hemosiderin (27.8%), and mild infiltration of heterophiles (33.3%). Also, the mucosa had traces of hemorrhage (27.8%) with free hemosiderin granules (11.1%).

Paramonostomum was found between the intestinal villi of the jejunum, however, without an evident inflammatory response around the parasites (Figures 13a, b). In the caeca, Catatropis and unidentified notocotylids were observed folded over the cecal villi and were associated with mild infiltration of the macrophages and traces of hemorrhage (Figure 14a, b). Overall, in the caeca, there were traces of hemorrhage (38.9%) and a diffuse inflammatory response with severe lymphocyte infiltration (94.4%), moderate heterophile (38.9%) and macrophage (33.3%) infiltration, and the presence of hemosiderin (27.8%).

Echinostoma mendax was observed mostly in the colonic lumen and, in some cases, the forebody was observed near the Lieberkühn crypts, causing local and mild erosion of the epithelium; also, some specimens were found in the cecal villi (Figure 15a-c). In general, the colonic mucosa had a mixed and diffuse inflammatory response that consisted of severe infiltration of lymphocytes (93.8%), and mild infiltration of heterophiles (43.8%), giant cells (18.8%), and macrophages (37.5%). Also, in one case, there were Splendore–Hoeppli lesions associated with severe fibrosis and an inflammatory response in the serosa of the colon.

Unidentified schistosomes and their eggs were recorded only by histopathology. Flukes were found inside the small blood vessels of the muscular layer and mucosa of the esophagus, small and large intestine, and caeca. These were isolated mainly from the colon (53.8%), followed by the duodenum (16%) and ileum (14.3%). Eggs were found in 66.7% of examined birds, located mostly in the colon (49.8%) and ileum (20.3%) mucosa. In general, adult parasites were not related to an inflammatory response, except in three cases. In the first, multiple schistosome flukes and their eggs, together with E. mendax in the lamina propria of the caeca, were surrounded by traces of hemorrhage and macrophages filled with hemosiderin. The other case was found in the esophagus, where a single fluke was surrounded by traces of hemorrhage and necrosis; however, there was no inflammatory response. In the third case, schistosome eggs in the jejunum and colonic mucosa were surrounded by the mild infiltration of heterophiles and lymphocytes.

At histopathology, scolices of R. cf. bulbocirrosus were found between the intestinal villi; they were surrounded by mild infiltration of macrophages with hemosiderin granules (Figure 16a, b). The duodenum showed a mixed inflammatory response, being severe for lymphocytes (80%) and mild for heterophiles (26.7%). Furthermore, traces of hemorrhage (26.7%) and free granules of hemosiderin (13.3%) were found. In the jejunum, there was a mixed and diffuse infiltration, which was characterized by severe and mild infiltration of lymphocytes (73.3%) and heterophiles (40%), respectively. In this organ, large tapeworms that were Sobolevicanthus sp.-like were seen in the intestinal lumen.

Discussion

As was noted in previous studies E. vogelsangi is a parasite from the gizzard (GONZÁLEZ-ACUÑA et al., 2010González-Acuña D, Moreno L, Cicchino A, Mironov S, Kinsella M. Checklist of the parasites of the black-necked swan, Cygnus melanocoryphus (Aves: Anatidae), with new records from Chile. Zootaxa 2010; 2637(1): 55-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637.1.3.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637....

; AGÜERO et al., 2016Agüero ML, Gilardoni C, Cremonte F, Diaz JI. Stomach nematodes of three sympatric species of anatid birds off the coast of Patagonia. J Helminthol 2016; 90(6): 663-667. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X15000899. PMid:26522056.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X15000...

; VALENZUELA et al., 2018Valenzuela G, Araya A, Oyarzún-Ruiz P, Muñoz P. Helminth fauna of the black-necked swan Cygnus melancoryphus (Aves: Anatidae) from Carlos Anwandter Nature Sanctuary, Valdivia, Chile. Rev Mex Biodivers 2018; 89(2): 568-571. http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2018.2.2323.

http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e....

), both under the koilin layer of the gastric pads, as well as in the muscle wall. In South America, this parasite seems to be restricted to the black-necked swan, reported in Argentina, Brazil (MCDONALD, 1969McDonald M. Catalogue of helminths of waterfowl (Anatidae). Washington: Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, Special Scientific Report; 1969.; FEDYNICH & THOMAS, 2008Fedynich A, Thomas N. Amidostomum and Epomidiostomum. In: Atkinson C, Thomas N, Hunter D. Parasitic diseases of wild birds. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 355-375.; AGÜERO et al., 2016Agüero ML, Gilardoni C, Cremonte F, Diaz JI. Stomach nematodes of three sympatric species of anatid birds off the coast of Patagonia. J Helminthol 2016; 90(6): 663-667. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X15000899. PMid:26522056.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X15000...

), and Chile (GONZÁLEZ-ACUÑA et al., 2010González-Acuña D, Moreno L, Cicchino A, Mironov S, Kinsella M. Checklist of the parasites of the black-necked swan, Cygnus melanocoryphus (Aves: Anatidae), with new records from Chile. Zootaxa 2010; 2637(1): 55-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637.1.3.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637....

; VALENZUELA et al., 2018Valenzuela G, Araya A, Oyarzún-Ruiz P, Muñoz P. Helminth fauna of the black-necked swan Cygnus melancoryphus (Aves: Anatidae) from Carlos Anwandter Nature Sanctuary, Valdivia, Chile. Rev Mex Biodivers 2018; 89(2): 568-571. http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2018.2.2323.

http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e....

). Present study is the first to provide information about pathology caused by this parasite. There is evidence from other species in the genus causing granulomatous lesions, hemorrhages in the mucosa, necrotic tissue, and fibrosis replacing the muscle fibers around nematodes (TUGGLE & CRITES, 1984Tuggle B, Crites J. The prevalence and pathogenicity of gizzard nematodes of the genera Amidostomum and Epomidiostomum (Trichostrongylidae) in the lesser snow goose (Chen caerulescens caerulescens). Can J Zool 1984; 62(9): 1849-1852. http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/z84-269.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/z84-269...

; GOMIS et al., 1996Gomis S, Didiuk A, Neufeld J, Wobeser G. Renal coccidiosis and other parasitologic conditions in lesser snow goose goslings at Tha-Anne River, West Coast Hudson Bay. J Wildl Dis 1996; 32(3): 498-504. http://dx.doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-32.3.498. PMid:8827676.

http://dx.doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-32.3...

) as those evidenced in preset research. The present findings are in agreement with those reported in the aforementioned studies; however, although hemorrhage was not evident, it was confirmed through Prussian blue stain (MYERS et al., 2012Myers R, McGavin M, Zachary J. Cellular adaptations, injury and death: morphologic, biochemical and genetic bases. In: Zachary J, McGavin M. Pathologic basis of veterinary disease. 5th ed. USA: Elsevier MOSBY; 2012. p. 2-59.). According to Fedynich & Thomas (2008)Fedynich A, Thomas N. Amidostomum and Epomidiostomum. In: Atkinson C, Thomas N, Hunter D. Parasitic diseases of wild birds. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 355-375., early inflammatory response consists of heterophiles being replaced by lymphocytes, macrophages, and fibrosis. Thus, fibrin bands, confirmed through Van Gieson’s stain, and lymphocytes would catalogue these lesions as chronic (ACKERMANN, 2012Ackermann M. Inflammation and wound healing. In: Zachary J, McGavin M. Pathologic basis of veterinary disease. 5th ed. USA: Elsevier MOSBY; 2012. p. 89-146.).

Tuggle & Crites (1984)Tuggle B, Crites J. The prevalence and pathogenicity of gizzard nematodes of the genera Amidostomum and Epomidiostomum (Trichostrongylidae) in the lesser snow goose (Chen caerulescens caerulescens). Can J Zool 1984; 62(9): 1849-1852. http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/z84-269.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/z84-269...

proposed that the parasitic load of over 25 worms of E. crami in the muscle layer could cause severe lesions. In the present study, the load varied from 5–337 nematodes that were mostly associated with severe lesions (66.7%). Nevertheless, such lesions were circumscribed only around parasites without reaching deeper areas. Another evident lesion was the loss of the koilin layer of the gizzard pads associated with multiple nematodes. A similar situation was recorded for Amidostomum, with erosion and brownish pigments in the gizzard pads associated with a poor body condition (MACNEILL, 1970MacNeill AC. Amidostomum anseris infection in wild swans and goldeneye ducks. Can Vet J 1970; 11(8): 164-167. PMid:5527953.; HARRADINE, 1982Harradine J. Some mortality patterns of Greater Magellan Geese on the Falkland Islands. Wildfowl 1982; 33: 7-11.; TUGGLE & CRITES, 1984Tuggle B, Crites J. The prevalence and pathogenicity of gizzard nematodes of the genera Amidostomum and Epomidiostomum (Trichostrongylidae) in the lesser snow goose (Chen caerulescens caerulescens). Can J Zool 1984; 62(9): 1849-1852. http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/z84-269.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/z84-269...

; PENNYCOTT, 1998Pennycott TW. Lead poisoning and parasitism in a flock of mute swans (Cygnus olor) in Scotland. Vet Rec 1998; 142(1): 13-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.142.1.13. PMid:9460217.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.142.1.13...

, 1999Pennycott TW. Causes of mortality in Mute Swans Cygnus olor in Scotland 1995-1996. Wildfowl 1999; 50: 11-20.). Similarly, in the present study, swans with such lesions showed a poor body condition (scoring 2–3 points). According to Tuggle & Crites (1984)Tuggle B, Crites J. The prevalence and pathogenicity of gizzard nematodes of the genera Amidostomum and Epomidiostomum (Trichostrongylidae) in the lesser snow goose (Chen caerulescens caerulescens). Can J Zool 1984; 62(9): 1849-1852. http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/z84-269.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/z84-269...

and Friend & Franson (1999)Friend M, Franson JC. Field manual of wildlife diseases: general field procedures and diseases of birds. Madison: USGS; 1999., a parasitic load of over 30 worms under the koilin layer caused evident erosion; meanwhile, Pennycott (1998)Pennycott TW. Lead poisoning and parasitism in a flock of mute swans (Cygnus olor) in Scotland. Vet Rec 1998; 142(1): 13-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.142.1.13. PMid:9460217.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.142.1.13...

suggested that a moderate (11–50 worms) to severe (over 50 worms) parasitic load is required to cause such erosion. The present swans hosted between 15–21 nematodes per bird in such lesions, which is in accordance with the findings of Pennycott (1998)Pennycott TW. Lead poisoning and parasitism in a flock of mute swans (Cygnus olor) in Scotland. Vet Rec 1998; 142(1): 13-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.142.1.13. PMid:9460217.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.142.1.13...

. This erosion is a mechanical consequence of parasite infestation, as it causes separation between the glandular mucosa and koilin layer (FEDYNICH & THOMAS, 2008Fedynich A, Thomas N. Amidostomum and Epomidiostomum. In: Atkinson C, Thomas N, Hunter D. Parasitic diseases of wild birds. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 355-375.). Nowicki et al. (1995)Nowicki A, Roby DD, Woolf A. Gizzard nematodes of Canada geese wintering in southern Illinois. J Wildl Dis 1995; 31(3): 307-313. http://dx.doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-31.3.307. PMid:8592349.

http://dx.doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-31.3...

and Friend and Franson (1999)Friend M, Franson JC. Field manual of wildlife diseases: general field procedures and diseases of birds. Madison: USGS; 1999. indicated that this was a cause of mortality, but only if there was an association with other stressors, such as malnutrition and co-infection with other parasites.

The nematode P. pulchrum has been recorded previously in the gizzard of Chauna torquata Oken, 1816 (Anseriformes) from Brazil (FREITAS & MENDONÇA, 1949Freitas JFT, Mendonça JM. Novo tricostrongilídeo parasito de “Chauna torquata” (Oken) (Nematoda). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1949; 47(1-2): 27-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761949000100002.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761949...

), and it has remained as the only record until present (see DURETTE-DESSET, 2009Durette-Desset MC. Strongylida, Trichostrongyloidea. In: Anderson R, Chabaud A, Willmot S. Keys to the nematode parasites of vertebrates: archival volume. London: CABI International; 2009. p. 110-177. http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/9781845935726.0110.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/9781845935726....

). Due to the migratory behavior of this swan (JOHNSGARD, 2010Johnsgard P. Ducks, geese, and swans of the world. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press; 2010.), it is plausible that this bird became parasitized in other countries, such as Brazil; however, one cannot discard that other local waterfowl could act as hosts in national territory as well. Regarding the pathology of this nematode, no information is currently available.

Capillaria pudendotecta has been reported from Asia and Europe in the caeca of Cygnus atratus Latham, 1790 and Cygnus olor Gmelin, 1789 (MCDONALD, 1969McDonald M. Catalogue of helminths of waterfowl (Anatidae). Washington: Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, Special Scientific Report; 1969.; TAMARU et al., 2015Tamaru M, Yamaki S, Jimenez LA, Sato H. Morphological and molecular genetic characterization of three Capillaria spp. (Capillaria anatis, Capillaria pudendotecta, and Capillaria madseni) and Baruscapillaria obsignata (Nematoda: Trichuridae: Capillariinae) in avians. Parasitol Res 2015; 114(11): 4011-4022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-015-4629-2. PMid:26204803.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-015-462...

). On the other hand, B. obsignata has been recorded only in the intestines of C. melancoryphus from Brazil, except for a report from Poland. Other records include C. atratus and C. olor from Asia, Europe, and North America (TRAVASSOS, 1915Travassos L. Contribuições para o conhecimento da fauna helmintolojica brasileira. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1915; 7(2): 146-172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761915000200002.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761915...

; WAKELIN, 1963Wakelin D. Capillaria obsignata Madsen, 1945 (Nematoda) from the black swan. J Helminthol 1963; 37(4): 381-386. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X00019982.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X00019...

; MCDONALD, 1969McDonald M. Catalogue of helminths of waterfowl (Anatidae). Washington: Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, Special Scientific Report; 1969.; PAPAZAHARIADOU et al., 2008Papazahariadou M, Diakou A, Papadopoulos E, Georgopoulou I, Komnenou A, Antoniadou-Sotiriadou K. Parasites of the digestive tract in free-ranging birds in Greece. J Nat Hist 2008; 42(5-8): 381-398. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222930701835357.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222930701835...

; GONZÁLEZ-ACUÑA et al., 2010González-Acuña D, Moreno L, Cicchino A, Mironov S, Kinsella M. Checklist of the parasites of the black-necked swan, Cygnus melanocoryphus (Aves: Anatidae), with new records from Chile. Zootaxa 2010; 2637(1): 55-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637.1.3.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637....

). The high prevalence recorded for both capillarids could be explained by the fact that these birds prefer to forage in low-depth areas (CORTI & SCHLATTER, 2002Corti P, Schlatter RP. Feeding ecology of the black-necked swan Cygnus melancoryphus in two wetlands of Southern Chile. Stud Neotrop Fauna Environ 2002; 37(1): 9-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1076/snfe.37.1.9.2118.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1076/snfe.37.1.9.21...

), thus reaching infective eggs in the sediment. Additional capillarid species have been recorded in C. melancoryphus from Chile: Capillaria sp. and Capillaria skrjabini (Lubimova, 1947) Moravec, 1982 (GONZÁLEZ-ACUÑA et al., 2010González-Acuña D, Moreno L, Cicchino A, Mironov S, Kinsella M. Checklist of the parasites of the black-necked swan, Cygnus melanocoryphus (Aves: Anatidae), with new records from Chile. Zootaxa 2010; 2637(1): 55-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637.1.3.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637....

; VALENZUELA et al., 2018Valenzuela G, Araya A, Oyarzún-Ruiz P, Muñoz P. Helminth fauna of the black-necked swan Cygnus melancoryphus (Aves: Anatidae) from Carlos Anwandter Nature Sanctuary, Valdivia, Chile. Rev Mex Biodivers 2018; 89(2): 568-571. http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2018.2.2323.

http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e....

). There are no data regarding the pathogenesis of C. pudendotecta; however, there are data for other cecal capillarids, including Capillaria phasianina Kotlan, 1940, which caused generalized typhlitis with worms penetrating the mucosa with infiltration of heterophiles and lymphocytes, and also fibrosis and necrosis of the mucosa (PINTO et al., 2004Pinto R, Tortelly R, Caldas R, Gomes D. Trichurid nematodes in ring-necked pheasants from backyard flocks of the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: frequency and pathology. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2004; 99(7): 721-726. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762004000700010. PMid:15654428.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762004...

). In the present study, some capillarid nematodes were recorded between the intestinal villi as well, although without a severe inflammatory response. According to Jortner et al. (1967)Jortner B, Helmboldt C, Pirozok R. Small intestinal histopathology of spontaneous capillariasis in the domestic fowl. Avian Dis 1967; 11(2): 154-169. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1588110. PMid:6035887.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1588110...

and Pinto et al. (2008)Pinto RM, Brener B, Tortelly R, Menezes RC, Muniz-Pereira LC. Capillariid nematodes in Brazilian turkeys, Meleagris gallopavo (Galliformes, Phasianidae): pathology induced by Baruscapillaria obsignata and Eucoleus annulatus (Trichinelloidea, Capillariidae). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2008; 103(3): 295-297. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762008005000017. PMid:18545854.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762008...

, parasitic loads between 200–400 worms are considered severe, causing hemorrhage, mixed inflammatory infiltration, and granulomas in the lamina propria. Meanwhile, loads with over 1,500 nematodes have been indicated as a cause of mortality (YABSLEY, 2008Yabsley M. Capillarid nematodes. In: Atkinson C, Thomas N, Hunter D. Parasitic Diseases of Wild Birds. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 463-497.). In the present survey, the parasitic load range for B. obsignata and C. pudendotecta was 1–33 and 1–53 worms, respectively, which is similar to Islam et al. (1988)Islam MR, Shaikh H, Baki MA. Prevalence and pathology of helminth parasites in domestic ducks of Bangladesh. Vet Parasitol 1988; 29(1): 73-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-4017(88)90009-X. PMid:3176302.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-4017(88)9...

and Pinto et al. (2004)Pinto R, Tortelly R, Caldas R, Gomes D. Trichurid nematodes in ring-necked pheasants from backyard flocks of the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: frequency and pathology. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2004; 99(7): 721-726. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762004000700010. PMid:15654428.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762004...

, who considered these loads as non-pathogenic to the host. On this basis, it is probable that the reported infection intensities have a minimal effect on these swans, which is in agreement with Yabsley (2008)Yabsley M. Capillarid nematodes. In: Atkinson C, Thomas N, Hunter D. Parasitic Diseases of Wild Birds. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 463-497., who states that despite the high prevalence of capillarid nematodes, the disease is infrequent because infection intensities are usually low.

Tetrameres (P.) fissipina has been reported in Cygnus buccinator Richardson, 1831, Cygnus columbianus Ord, 1815, and Cygnus cygnus Linnaeus, 1758 from Asia and North America (MACNEILL, 1970MacNeill AC. Amidostomum anseris infection in wild swans and goldeneye ducks. Can Vet J 1970; 11(8): 164-167. PMid:5527953.; YOSHINO et al., 2009Yoshino T, Uemura J, Endoh D, Kaneko M, Osa Y, Asakawa M. Parasitic nematodes of anseriform birds in Hokkaido, Japan. Helminthologia 2009; 46(2): 117-122. http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-0023-x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-002...

). Previous reports in Neotropical waterfowl include Anas platyrhynchos, Cairina moschata Linnaeus, 1758, and Lophonetta specularioides King, 1828 from Argentina and Brazil (VICENTE et al., 1995Vicente JJ, Rodrigues HO, Gomes DC, Pinto RM. Nematóides do Brasil. Parte IV: nematóides de aves. Rev Bras Zool 1995; 12(Suppl. 1): 1-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81751995000500001.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81751995...

; AGÜERO et al., 2016Agüero ML, Gilardoni C, Cremonte F, Diaz JI. Stomach nematodes of three sympatric species of anatid birds off the coast of Patagonia. J Helminthol 2016; 90(6): 663-667. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X15000899. PMid:26522056.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X15000...

). Meanwhile, for C. melancoryphus has been isolated once from an unknown location (GONZÁLEZ-ACUÑA et al., 2010González-Acuña D, Moreno L, Cicchino A, Mironov S, Kinsella M. Checklist of the parasites of the black-necked swan, Cygnus melanocoryphus (Aves: Anatidae), with new records from Chile. Zootaxa 2010; 2637(1): 55-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637.1.3.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637....

). Regarding lesions in the proventriculus, these are caused only by female worms, as they are embedded in the gastric glands, causing mucosal thickening with infiltration of lymphocytes, heterophiles, and glandular atrophy (PANDE et al., 1960Pande BP, Rai P, Srivastava JS. A note on some pathogenic effects observed in certain nematode infections of wild aquatic birds with remarks on its significance. Poult Sci 1960; 39(5): 1121-1125. http://dx.doi.org/10.3382/ps.0391121.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3382/ps.0391121...

; ISLAM et al., 1988Islam MR, Shaikh H, Baki MA. Prevalence and pathology of helminth parasites in domestic ducks of Bangladesh. Vet Parasitol 1988; 29(1): 73-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-4017(88)90009-X. PMid:3176302.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-4017(88)9...

). While an inflammatory response was found in the mucosa, there was an absence of female worms.

Notocotylus attenuatus is considered a common helminth of waterfowl; in the case of swans, it has been isolated in the caeca and colon of C. atratus, C. columbianus, C. cygnus, and C. olor from Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America (MCDONALD, 1969McDonald M. Catalogue of helminths of waterfowl (Anatidae). Washington: Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, Special Scientific Report; 1969.; PAPAZAHARIADOU et al., 2008Papazahariadou M, Diakou A, Papadopoulos E, Georgopoulou I, Komnenou A, Antoniadou-Sotiriadou K. Parasites of the digestive tract in free-ranging birds in Greece. J Nat Hist 2008; 42(5-8): 381-398. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222930701835357.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222930701835...

). Conversely, in South American waterfowl, it has been recorded in Spatula versicolor Vieillot, 1816 and C. melancoryphus from Argentina (BOERO et al., 1972Boero JJ, Led JE, Brandetti E. Algunos parásitos de la avifauna argentina. Analecta Vet 1972; 4(1): 17-34.). Notocotylus breviserialis was experimentally isolated from ducks and fowl in North America (STUNKARD, 1967aStunkard HW. The morphology, life-history, and systematic relations of the digenetic trematode, Uniserialis breviserialis sp. nov., (Notocotylidae), a parasite of the bursa fabricius of birds. Biol Bull 1967a; 132(2): 266-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1539894. PMid:29332442.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1539894...

), and was also found in the bursa of Fabricius of Amazonetta brasiliensis Gmelin, 1789 and Anas bahamensis Linnaeus, 1758 from Brazil (MUNIZ-PEREIRA & AMATO, 1995Muniz-Pereira LC, Amato SB. Natural hosts of Notocotylus breviserialis (Digenea, Notocotylidae) parasite of Brazilian waterfowl. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1995; 90(6): 711-714. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761995000600011.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761995...

). Uniserialis gippyensis is located in the bursa of Fabricius and occasionally in the caeca of juvenile birds, while in adult birds, it parasitizes cloaca. It has been isolated in A. platyrhynchos, Anas superciliosa Gmelin, 1789, Branta canadensis Linnaeus, 1758, and Tadorna variegata Gmelin, 1789 from England and New Zealand (BEVERLEY-BURTON, 1958Beverley-Burton M. A new notocotylid trematode, Uniserialis gippyensis gen. et sp. nov., from the mallard, Anas platyrhyncha platyrhyncha L. J Parasitol 1958; 44(4): 412-415. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3274325. PMid:13564355.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3274325...

; BISSET, 1977Bisset S. Notocotylus tadornae n. sp. and Notocotylus gippyensis (Beverley-Burton, 1958) (Trematoda: Notocotylidae) from waterfowl in New Zealand: morphology, life history and systematic relations. J Helminthol 1977; 51(4): 365-372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X00007720.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X00007...

; JONES et al., 2005Jones A, Bray RA, Gibson DI. Keys to the Trematoda: volume 2. London: CABI Publishing and The Natural History Musem; 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/9780851995878.0000.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/9780851995878....

). Uniserialis tadornae, unlike the former, parasitizes only the caeca of waterfowl as T. variegata from New Zealand (BISSET, 1977Bisset S. Notocotylus tadornae n. sp. and Notocotylus gippyensis (Beverley-Burton, 1958) (Trematoda: Notocotylidae) from waterfowl in New Zealand: morphology, life history and systematic relations. J Helminthol 1977; 51(4): 365-372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X00007720.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X00007...

). Catatropis chilinae was previously isolated from the caeca of hens and ducks as experimental hosts, in addition to its natural waterfowl host Chloephaga poliocephala Sclater, 1857 from Argentina (FLORES & BRUGNI, 2003Flores V, Brugni N. Catatropis chilinae n. sp. (Digenea: Notocotylidae) from Chilina dombeiana (Gastropoda: Pulmonata) and notes on its life-cycle in Patagonia, Argentina. Syst Parasitol 2003; 54(2): 89-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1022593810479. PMid:12652062.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:102259381047...

). Regarding the black-necked swan, Catatropis verrucosa (Frölich, 1789) Odhner, 1905 was reported by Valenzuela et al. (2018)Valenzuela G, Araya A, Oyarzún-Ruiz P, Muñoz P. Helminth fauna of the black-necked swan Cygnus melancoryphus (Aves: Anatidae) from Carlos Anwandter Nature Sanctuary, Valdivia, Chile. Rev Mex Biodivers 2018; 89(2): 568-571. http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2018.2.2323.

http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e....

in Chile. In the case of P. alveatum, this species has been reported in C. cygnus and C. olor from Asia, Europe, and North America, while P. chabaudi has been isolated in Haematopus ostralegus Linnaeus, 1758 (Charadriiformes) and A. platyrhynchos from Europe (STUNKARD, 1967bStunkard HW. Studies on the trematode genus Paramonostomum Lühe, 1909 (Digenea: notocotylidae). Biol Bull 1967b; 132(1): 133-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1539883. PMid:6040022.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1539883...

; MCDONALD, 1969McDonald M. Catalogue of helminths of waterfowl (Anatidae). Washington: Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, Special Scientific Report; 1969.). Regarding C. melancoryphus, González-Acuña et al. (2010)González-Acuña D, Moreno L, Cicchino A, Mironov S, Kinsella M. Checklist of the parasites of the black-necked swan, Cygnus melanocoryphus (Aves: Anatidae), with new records from Chile. Zootaxa 2010; 2637(1): 55-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637.1.3.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637....

isolated Paramonostomum sp.

With respect to lesions, Griffiths et al. (1976)Griffiths HJ, Gonder E, Pomeroy BS. An outbreak of trematodiasis in domestic geese. Avian Dis 1976; 20(3): 604-606. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1589396. PMid:962765.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1589396...

stated that only high numbers of N. attenuatus are associated with severe enteritis; however, low numbers would not be responsible for tissue damage. According to Radlett (1979)Radlett AJ. Excystation of Notocotylus attenuatus (Rudolphi, 1809) Kossack, 1911 (Trematoda: Notocotylidae) and their localization in the caecum of the domestic fowl. Parasitology 1979; 79(3): 411-416. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000053804.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000053...

, juvenile flukes of N. attenuatus only cause a light local compression. Adult worms are folded to the villi, aided by their ventral papillae and body concavity, flattening the epithelium with no additional lesions (RADLETT, 1979Radlett AJ. Excystation of Notocotylus attenuatus (Rudolphi, 1809) Kossack, 1911 (Trematoda: Notocotylidae) and their localization in the caecum of the domestic fowl. Parasitology 1979; 79(3): 411-416. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000053804.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000053...

; FRIED & GAINSBURG, 1980Fried B, Gainsburg DM. Concurrent infections of cecal trematodes, Zygocotyle lunata and Notocotylus sp., in the domestic chick and observations on host-parasite relationships of Notocotylus sp. J Parasitol 1980; 66(3): 502-505. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3280755. PMid:7391892.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3280755...

; MACKINNON, 1982MacKinnon BM. The histology, ultrastructure, and histochemistry of the ventral surfaces of Catatropis verrucosa (Froelich, 1789) Odhner, 1905 and Paramonostomum alveatum (Mehlis in Creplin, 1846) Lühe, 1909 (Digenea: notocotylidae). Can J Zool 1982; 60(10): 2434-2441. http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/z82-311.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/z82-311...

). Furthermore, Islam et al. (1988)Islam MR, Shaikh H, Baki MA. Prevalence and pathology of helminth parasites in domestic ducks of Bangladesh. Vet Parasitol 1988; 29(1): 73-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-4017(88)90009-X. PMid:3176302.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-4017(88)9...

recorded an infection with 130 worms of C. verrucosa with no pathological changes in tissues. For Paramonostomum, parasitic loads of over 50,000 worms were related to necrosis and severe inflammation of the mucosa, causing the host’s death (STUNKARD, 1967bStunkard HW. Studies on the trematode genus Paramonostomum Lühe, 1909 (Digenea: notocotylidae). Biol Bull 1967b; 132(1): 133-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1539883. PMid:6040022.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1539883...

; WOBESER, 1997Wobeser G. Metazoan parasites. In: Wobeser G. Diseases of wild waterfowl. Saskatoon: Springer Science; 1997. p. 129-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-5951-1_10.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-595...

). In the present histopathological analysis, Notocotylidae trematodes were found over the cecal mucosa and between the villi of the jejunum; nevertheless, the inflammatory response was mild and local. Paramonostomum alveatum was the fluke with the highest infection intensity, as 2,589 flukes were hosted by one swan. Despite the aforementioned findings, Wobeser (1997)Wobeser G. Metazoan parasites. In: Wobeser G. Diseases of wild waterfowl. Saskatoon: Springer Science; 1997. p. 129-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-5951-1_10.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-595...

and Huffman (2008)Huffman J. Trematodes. In: Atkinson C, Thomas N, Hunter D. Parasitic diseases of wild birds. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 223-245. stated that although most avian flukes are not responsible for significant disease to their hosts, pathogenicity could vary between different species. Unfortunately, there are no studies on the pathology of Uniserialis; however, as they use a similar attachment mechanism to the mucosa, as well as to other notocotylid flukes, is possible they have a minimal effect over the host as well.

Echinostoma echinatum has been isolated in Asia, Europe, and South America. It was experimentally isolated from ducks, hens, and pigeons from Brazil. Currently, the natural definitive host in the neotropics was unknown until now; however, the authors suggested that the host would be a bird (LIE & BASCH, 1966Lie K, Basch P. Life history of Echinostoma barbosai sp. n. (Trematoda: echinostomatidae). J Parasitol 1966; 52(6): 1052-1057. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3276346. PMid:5926328.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3276346...

; FRIED & GRACZYK, 2004Fried B, Graczyk TK. Recent Advances in the Biology of Echinostoma species in the “revolutum” Group. Adv Parasitol 2004; 58: 139-195. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0065-308X(04)58003-X. PMid:15603763.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0065-308X(04)...

). Conversely, Echinostoma mendax has been previously isolated in Dendrocygna viduata Linnaeus, 1766, Neochen jubata von Spix, 1825, A. brasiliensis, C. moschata, and C. melancoryphus from Argentina, Brazil, and Venezuela (TRAVASSOS et al., 1969Travassos L, Freitas JFT, Kohn A. Trematódeos do Brasil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1969; 67(1): 1-886. PMid:5397756.; BOERO et al., 1972Boero JJ, Led JE, Brandetti E. Algunos parásitos de la avifauna argentina. Analecta Vet 1972; 4(1): 17-34.; FERNANDES et al., 2015Fernandes BMM, Justo MCN, Cárdenas QC, Cohen SC. South American Trematodes parasites of birds and mammals. Rio de Janeiro: Oficina de Livros; 2015.); thus, it seems to be restricted to South America. Previous surveys from black-necked swans have recorded Echinostoma trivolvis Cort, 1914 and E. revolutum s. l. from Chile (GONZÁLEZ-ACUÑA et al., 2010González-Acuña D, Moreno L, Cicchino A, Mironov S, Kinsella M. Checklist of the parasites of the black-necked swan, Cygnus melanocoryphus (Aves: Anatidae), with new records from Chile. Zootaxa 2010; 2637(1): 55-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637.1.3.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2637....

; VALENZUELA et al., 2018Valenzuela G, Araya A, Oyarzún-Ruiz P, Muñoz P. Helminth fauna of the black-necked swan Cygnus melancoryphus (Aves: Anatidae) from Carlos Anwandter Nature Sanctuary, Valdivia, Chile. Rev Mex Biodivers 2018; 89(2): 568-571. http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2018.2.2323.

http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e....

).

Members from the family Echinostomatidae are indicated as low pathogenic parasites; however, parasitic loads of over 200 worms are considered severe and associated with important mixed inflammatory infiltration (KITCHELL et al., 1947Kitchell RL, Cass JS, Sautter JH. An infestation in domestic turkeys with intestinal flukes. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1947; 111(848): 379-381. PMid:20268057.). On the other hand, loads of over 300 worms are responsible for hemorrhagic enteritis, causing the death of juvenile birds (SOULSBY, 1987Soulsby EJL. Parasitología y enfermedades parasitarias en los animales domésticos. 7a ed. México D.F: Editorial Interamericana/McGraw-Hill; 1987.; KIM & FRIED, 1989Kim S, Fried B. Pathological effects of Echinostoma caproni (Trematoda) in the domestic chick. J Helminthol 1989; 63(3): 227-230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X00009020. PMid:2794456.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X00009...

). In comparison to the aforementioned studies, the recorded loads (e.g., 43 flukes as a maximum load) could not be considered severe. However, in murine experimental models, a parasitic load of 45 worms of Echinostoma caproni Richard, 1964 was considered severe and resulted in mortality (TOLEDO, 2009Toledo R. Immunology and pathology of Echinostome infections in the definitive host. In: Fried B, Toledo R. The Biology of Echinostomes – from the molecule to the community. New York: Springer Science+Business; 2009. p. 185-206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-09577-6_8

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-0957...

). Even though they exhibited a similar parasitic load, the hosts and parasites are different; thus, the resulting pathogenesis may differ as well. Alternatively, in the avian model; mild to moderate infections can cause tissue damage at the area of penetration of the peristomic disk (MUCHA et al., 1990Mucha KH, Huffman JE, Fried B. Mallard ducklings (Anas platyrhynchos) experimentally infected with Echinostoma trivolvis (Digenea). J Parasitol 1990; 76(4): 590-592. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3282851. PMid:2380872.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3282851...

; HUFFMAN, 2000Huffman J. Echinostomes in veterinary and wildlife parasitology. In: Fried B, Graczyk T. Echinostomes as experimental models for biological research. USA: Springer Science+Business; 2000. p. 59-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-9606-0_3.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-960...

; MULLICAN et al., 2001Mullican S, Huffman J, Fried B. Infectivity and comparative pathology of Echinostoma caproni, Echinostoma revolutum, and Echinostoma trivolvis (Trematoda) in the domestic chick. Comp Parasitol 2001; 68(2): 256-259.) or, in the opposite case, low numbers of parasites might not cause any lesions at all (GRIFFITHS et al., 1976Griffiths HJ, Gonder E, Pomeroy BS. An outbreak of trematodiasis in domestic geese. Avian Dis 1976; 20(3): 604-606. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1589396. PMid:962765.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1589396...

). Similarly, in the present case, echinostomes were found associated with traces of hemorrhage and superficial erosion of the epithelium; however, there was no evidence of severe inflammatory response around the parasites. Unusually, an immature E. mendax was found over the cecal epithelium causing local erosion. Furthermore, in one case of co-parasitism with several Schistosomatidae flukes and eggs, there was an evident inflammatory response around it. It is probable this inflammatory response could have resulted from parasitic interactions in the cecum, although experimental studies are required to validate this hypothesis.

Several genera of Schistosomatidae flukes have been recorded parasitizing swans, such as Bilharziella Looss, 1899, Dendritobilharzia, and Trichobilharzia Skrjabin & Zakharow, 1920 in C. columbianus, C. cygnus, and C. olor from Asia, Europe, and North America (MCDONALD, 1969McDonald M. Catalogue of helminths of waterfowl (Anatidae). Washington: Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, Special Scientific Report; 1969.; PENNYCOTT, 1999Pennycott TW. Causes of mortality in Mute Swans Cygnus olor in Scotland 1995-1996. Wildfowl 1999; 50: 11-20.). Meanwhile in South America, there are few records of Trichobilharzia parasitizing waterfowl from Argentina and Brazil (FERNANDES et al., 2015Fernandes BMM, Justo MCN, Cárdenas QC, Cohen SC. South American Trematodes parasites of birds and mammals. Rio de Janeiro: Oficina de Livros; 2015.; FLORES et al., 2015Flores V, Brant SV, Loker ES. Avian schistosomes from the South American endemic gastropod genus Chilina (Pulmonata: Chilinidae), with a brief review of South American Schistosome Species. J Parasitol 2015; 101(5): 565-576. http://dx.doi.org/10.1645/14-639. PMid:26186680.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1645/14-639...

). Paré & Black (1999)Paré JA, Black SR. Schistosomiasis in a collection of captive Chilean flamingos (Phoenicopterus chilensis). J Avian Med Surg 1999; 13(3): 187-191. reported Dendritobilharzia sp. from Phoenicopterus chilensis Molina, 1782 (Phoenicopteriformes) in a Canadian zoo; however, the authors speculated that these birds arrived parasitized from Chile; thus, this finding represents the only reported case from a Chilean wild anatid (see HINOJOSA-SÁEZ & GONZÁLEZ-ACUÑA, 2005Hinojosa-Sáez A, González-Acuña D. Estado actual del conocimiento de helmintos en aves silvestres de Chile. Gayana (Concepc) 2005; 69(2): 241-253. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-65382005000200004.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-65382005...

). Therefore, this finding is crucial given the high prevalence recorded and the presence of eggs in mucosa, suggesting that C. melancoryphus is a suitable final host (PENNYCOTT, 1998Pennycott TW. Lead poisoning and parasitism in a flock of mute swans (Cygnus olor) in Scotland. Vet Rec 1998; 142(1): 13-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.142.1.13. PMid:9460217.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.142.1.13...

).

The pathology of schistosomes is associated with eggs arriving from the bloodstream into the lamina propria, triggering a granulomatous reaction associated with a mixed inflammatory response (PARÉ & BLACK, 1999Paré JA, Black SR. Schistosomiasis in a collection of captive Chilean flamingos (Phoenicopterus chilensis). J Avian Med Surg 1999; 13(3): 187-191.; HUFFMAN & FRIED, 2008Huffman J, Fried B. Schistosomes. In: Atkinson C, Thomas N, Hunter D. Parasitic diseases of wild birds. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 246-260). Similarly, in the present study, eggs were associated with necrosis and a mixed inflammatory response, although it was mostly mild, except for the case of co-parasitism with E. mendax. Meanwhile, a remarkable inflammatory response around helminths was rare, as reported by Pennycott (1998)Pennycott TW. Lead poisoning and parasitism in a flock of mute swans (Cygnus olor) in Scotland. Vet Rec 1998; 142(1): 13-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.142.1.13. PMid:9460217.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.142.1.13...

.

Sobolevicanthus sp. and Sobolevicanthus gracilis Zeder, 1803 have been recorded in C. atratus, C. buccinator, C. cygnus, and C. olor from Asia, Europe, and North America (MCDONALD, 1969McDonald M. Catalogue of helminths of waterfowl (Anatidae). Washington: Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, Special Scientific Report; 1969.; BLUS et al., 1989Blus L, Stroud R, Reiswig B, McEneaney T. Lead poisoning and other mortality factors in trumpeter swans. Environ Toxicol Chem 1989; 8(3): 263-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620080308.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620080308...

; ZUCHOWSKA, 1997Zuchowska E. Helminth fauna Anseriformes (Aves) in the Lodz Zoological Garden. Wiad Parazytol 1997; 43(2): 213-221. PMid:9424942.). In the neotropics there are few findings, with a report in waterfowl from Mexico: Sobolevicanthus krabella Hughes, 1940 and S. gracilis; (FARIAS & CANARIS, 1986Farias JD, Canaris AG. Gastrointestinal helminths of the Mexican duck, Anas platyrhynchos diazi Ridgway, from North Central Mexico and Southwestern United States. J Wildl Dis 1986; 22(1): 51-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-22.1.51. PMid:3951061.

http://dx.doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-22.1...

; MARTÍNEZ-HARO et al., 2012Martínez-Haro M, Sánchez-Nava P, Salgado-Maldonado G, Rodríguez-Romero FDJ. Helmintos gastrointestinales en aves acuáticas de la subcuenca alta del río Lerma, México. Rev Mex Biodivers 2012; 83(1): 36-41.). For the black-necked swan, Pfeiffer (1960)Pfeiffer H. Hymenosphenacanthus bulbocirrosus spec. nov. (Hymenolepididae), ein neuer bandwurm des schwarzhalsschwanes. Z Parasitenkd 1960; 20(4): 345-349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00261223. PMid:13735165.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00261223...

isolated R. bulbocirrosus from captive birds in Austria; nevertheless, the author specified that the birds died soon after their arrival from Argentina. The reduced records for both genera could reflect the limited parasitological studies on Neotropical waterfowl (AGÜERO et al., 2016Agüero ML, Gilardoni C, Cremonte F, Diaz JI. Stomach nematodes of three sympatric species of anatid birds off the coast of Patagonia. J Helminthol 2016; 90(6): 663-667. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X15000899. PMid:26522056.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X15000...

).

With respect to the pathology of both tapeworms, there is no specific description; however, there are descriptions for other species of the same family. According to McDonald (1998)McDonald S. The parasitology of the black stilt (Himantopus novaezelandiae). Conservation Advisory Service Notes No. 185. Wellington: Department of Conservation; 1998. and McLaughlin (2008)McLaughlin J. Cestodes. In: Atkinson C, Thomas N, Hunter D. Parasitic Diseases of Wild Birds. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 261-276., the pathogenicity of most tapeworms is unknown; however, in general terms, they are considered as low or non-pathogenic to birds. For example, Morishita & Schaul (2007)Morishita T, Schaul J. Parasites of birds. In: Baker D. Flynn’s Parasites of laboratory animals. Iowa: Blackwell Publishing; 2007. p. 217-301. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470344552.ch10.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470344552....

indicated that a single bird could harbor hundreds of parasites without evident tissue damage. Nevertheless, tapeworms of considerable size could occlude the intestinal lumen and cause patent enteritis (JENNINGS et al., 1961Jennings AR, Soulsby EJL, Wainwright CB. An outbreak of disease in mute swans at an Essex Reservoir. Bird Study 1961; 8(1): 19-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00063656109475984.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00063656109475...

; FRIEND & FRANSON, 1999Friend M, Franson JC. Field manual of wildlife diseases: general field procedures and diseases of birds. Madison: USGS; 1999.). However, occlusion was not reported in the present study despite the fact that certain swans harbored important loads of Sobolevicanthus sp., which is similar to what was reported by Harradine (1982)Harradine J. Some mortality patterns of Greater Magellan Geese on the Falkland Islands. Wildfowl 1982; 33: 7-11.. Parasitic loads of over 2,200 R. bulbocirrosus were recorded in a single swan, although on a few occasions, scolices were found to penetrate the duodenum, causing only a local inflammatory response and superficial erosion. On the contrary, Sobolevicanthus was found free in the intestinal lumen. Thus, it seems that these tapeworms are not a primary cause of enteritis, as McDonald (1998)McDonald S. The parasitology of the black stilt (Himantopus novaezelandiae). Conservation Advisory Service Notes No. 185. Wellington: Department of Conservation; 1998., Morishita & Schaul (2007)Morishita T, Schaul J. Parasites of birds. In: Baker D. Flynn’s Parasites of laboratory animals. Iowa: Blackwell Publishing; 2007. p. 217-301. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470344552.ch10.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470344552....

, and McLaughlin (2008)McLaughlin J. Cestodes. In: Atkinson C, Thomas N, Hunter D. Parasitic Diseases of Wild Birds. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 261-276. suggested.

In terms of histopathology, the reported inflammatory responses could not be exclusively attributed to parasites, as other microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi), non-diagnosed conditions, and toxins, among others, could be responsible as well (MACNEILL, 1970MacNeill AC. Amidostomum anseris infection in wild swans and goldeneye ducks. Can Vet J 1970; 11(8): 164-167. PMid:5527953.; BLUS et al., 1989Blus L, Stroud R, Reiswig B, McEneaney T. Lead poisoning and other mortality factors in trumpeter swans. Environ Toxicol Chem 1989; 8(3): 263-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620080308.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620080308...

; PENNYCOTT, 1998Pennycott TW. Lead poisoning and parasitism in a flock of mute swans (Cygnus olor) in Scotland. Vet Rec 1998; 142(1): 13-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.142.1.13. PMid:9460217.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.142.1.13...

, 1999Pennycott TW. Causes of mortality in Mute Swans Cygnus olor in Scotland 1995-1996. Wildfowl 1999; 50: 11-20.; FEDYNICH & THOMAS, 2008Fedynich A, Thomas N. Amidostomum and Epomidiostomum. In: Atkinson C, Thomas N, Hunter D. Parasitic diseases of wild birds. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 355-375.). Furthermore, all examined swans were found dead, so the role of other noxa contributing to this situation is probable. Only for E. vogelsangi did granulomatous lesions and loss of most of the koilin layer of the gizzard pose a potential threat to birds (FRIEND & FRANSON, 1999Friend M, Franson JC. Field manual of wildlife diseases: general field procedures and diseases of birds. Madison: USGS; 1999.); even so, the latter lesion was uncommon. Splendore–Hoeppli is an antigen–antibody complex with stick-shaped, homogenous, eosinophilic protein material associated with bacteria or foreign bodies (ACKERMANN, 2012Ackermann M. Inflammation and wound healing. In: Zachary J, McGavin M. Pathologic basis of veterinary disease. 5th ed. USA: Elsevier MOSBY; 2012. p. 89-146.). It was evident in a single swan, both in its colonic serosa and in the muscle wall of the gizzard. In the latter, there was a loss of the koilin layer, which could predispose the swan to secondary bacterial colonization (OLIVER, 1952Oliver WT. Amidostomiasis in domestic geese. Can J Comp Med Vet Sci 1952; 16(6): 235-237. PMid:17648576.); in fact, these bacterial colonies were evidenced at histopathology of both organs. In addition, schistosome eggs can cause these lesions as well, reaching several organs through hematogenous spread (HUFFMAN & FRIED, 2008Huffman J, Fried B. Schistosomes. In: Atkinson C, Thomas N, Hunter D. Parasitic diseases of wild birds. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 246-260). However, these flukes were not isolated in that bird, although its absence may be related to bias, as a limited number of cuts per organ was performed for histopathology.