Abstract

The reinforcement assembly of precast concrete elements necessitates a high degree of precision. However, manual inspections can be both time-consuming and prone to errors. This study explores videogrammetry as a cost-effective alternative to laser scanning for generating geometric models that aid in quality inspections before concreting. A case study was conducted to evaluate video capture and image processing within a manufacturing setting. The findings revealed that filming reinforcements mounted on metallic supports significantly improved accuracy. Furthermore, optimal lighting, a frame rate of three frames per second, and high-quality settings enhanced both the detail and visualization of the models.

Keywords

Construction 4.0; Dimensional quality; Reinforcement cages; Photogrammetry; Point clouds

Resumo

A montagem das armaduras de elementos pré-moldados de concreto exige um alto grau de precisão. No entanto, as inspeções manuais podem ser demoradas e suscetíveis a erros. Este estudo investiga a videogrametria como uma alternativa econômica ao escaneamento a laser para a geração de modelos geométricos que auxiliem nas inspeções de qualidade antes da concretagem. Um estudo de caso foi realizado para avaliar a captura de vídeo e o processamento de imagens em ambiente fabril. Os resultados revelaram que a filmagem das armaduras montadas em suportes metálicos melhorou significativamente a precisão. Além disso, iluminação adequada, taxa de três quadros por segundo e configurações de alta qualidade aumentaram o nível de detalhamento e a visualização dos modelos.

Palavras-chave

Construção 4.0; Qualidade dimensional; Armaduras de aço; Fotogrametria; Nuvens de pontos

Introduction

In the construction industry, the sector specializing in precast components has become one of the most demanding in terms of dimensional quality control during manufacturing. This focus is particularly important for elements such as reinforcement bars, slabs, concrete panels, and bridge deck beams. Wu et al. (2024) highlight this emphasis, stemming from a growing demand for prefabricated components in recent years, as noted by Wang, Cheng and Sohn (2017). Precision in producing precast reinforced concrete elements is critical for two primary reasons: the structural integrity relies on the correct positioning of reinforcement within the formwork, and during on-site assembly, any deviation from the required manufacturing tolerance can cause misalignments with adjacent reinforced concrete components (Qureshi et al., 2024). Therefore, active quality inspection is essential to prevent such issues.

Traditional inspection methods are labor-intensive and pose safety risks for inspectors (Yuan et al., 2021). A skilled and experienced inspector typically conducts dimensional reinforcement inspections, checking for irregular spacing, length, and diameter irregularities using direct measurement tools such as measuring tapes and calipers (Yuan et al., 2021). However, this process is not only time-consuming but also prone to errors. Furthermore, conventional inspection often requires inspectors to walk on the reinforcement to verify dimensions and spacing, which exposes them to risks such as falls and puncture injuries. Moreover, walking on the reinforcement may compromise its structural integrity (Kim; Thedja; Wang, 2020).

To address these challenges, some researchers have advocated for the adoption of digital technologies for geometric data acquisition, including Li et al. (2022) and Silva and Costa (2022). Consequently, the construction industry has seen an uptick in the use of point cloud data for various applications (Wang; Tan; Mei, 2020), including geometric quality inspection (Kim et al., 2023; Wang; Chen; Sohn, 2017; Yuan et al., 2021). Point clouds, which are three-dimensional points within a 3D coordinate system, primarily represent an object’s external surfaces and can be obtained through methods including laser scanning, photogrammetry, and videogrammetry (Tang et al., 2010; Wang; Tan; Mei, 2020).

Laser scanning operates based on the emission and reflection of a laser beam towards the object being recorded; upon contact, part of the laser signal is reflected back to the sensor, facilitating distance measurement (Groetelaars, 2015). Despite the varying levels of digital maturity in the construction industry, advanced technologies such as terrestrial laser scanners are being employed for dimensional verification of structural elements in some contexts. However, adopting such technologies varies, as tasks in other contexts are still performed manually without technological assistance (Yuan et al., 2021). One of the main reasons for this disparity is that laser scanning technology requires a high level of technical expertise and significant initial investment (Sun; Zhang, 2018; Peterson; Lopez; Munjy, 2019).

Since 2020, tablets and smartphones equipped with light detection and ranging sensors, notably those from Apple’s lineup, including the iPad Pro, iPhone 12 Pro, and iPhone 12 Pro Max, have been introduced to the market (Paukkonen, 2023). These devices represent a relatively novel set of tools that necessitate further research and experimentation to evaluate their performance, limitations, and the best practices for their use in metric surveying of objects.

Digital image processing techniques, notably photogrammetry and videogrammetry, stand out among the most cost-effective scanning systems. Utilizing photographs or video frames, these methods capture objects or spaces from various perspectives to create point clouds and polygonal meshes (Liu et al., 2015). Their cost-effectiveness primarily derives from the use of standard digital cameras, tablets, or smartphones for image or video capture, with the subsequent processing executed on either a mobile device or computer via photogrammetric reconstruction software.

Videogrammetry, in particular, offers the benefit of faster data capture in the field through the continuous and sequential recording of scenes. Emerging amid the proliferation of more accessible digital cameras (Murtiyoso; Grussenmeyer, 2021), videogrammetry is not as widely recognized or employed as traditional digital photogrammetry, despite its efficiency in rapidly gathering extensive data volumes. Nonetheless, with the ongoing improvements in the quality and resolution of affordable video recording devices, including consumer-grade digital cameras and smartphones, videogrammetry’s potential applications are expected to grow substantially.

In light of this context, this study investigated the application of videogrammetry for creating geometric models of precast concrete reinforcement to facilitate quality inspection processes prior to concreting within a manufacturing setting. Geometric models were generated using videos captured by smartphones and processed with photogrammetric software. The case study offers insightful observations and lessons regarding the data acquisition and processing phases, contributing to the body of knowledge on this subject.

Literature review

This section presents a literature review on quality control in precast concrete alongside the concepts of photogrammetry and videogrammetry, with an emphasis on their roles in quality management systems.

Quality control of precast concrete

Establishing standards for executive procedures and inspections is crucial for reducing variability in production chains (Silva et al., 2025). In the precast modular elements industry, quality control is of paramount importance due to the necessity for high dimensional precision. Production inconsistencies can result in failures in element strength, inappropriate structural behavior, or assembly incompatibilities, underscoring the significance of quality inspections throughout the manufacturing process (Araújo; Silva; Melo, 2024).

Standards such as NBR 9062 (ABNT, 2017), NBR 6118 (ABNT, 2023a), and NBR 14931 (ABNT, 2023b) highlight the critical nature of quality in the manufacturing of precast elements, especially concerning the assembly and positioning of reinforcement bars. These standards mandate detailed and accurate documentation for production, comprehensive inspections prior to concreting, and adherence to specifications on the arrangement, spacing, and fixation of reinforcement bars to maintain design integrity. According to Shu et al. (2023), key parameters for quality inspection include reinforcement bar diameter, spacing between bars, and reinforcement bar length to ensure compliance with specifications.

Despite their significance, preliminary inspection procedures for precast elements primarily involve mechanical measurements and visual inspections, which are both time-intensive and susceptible to human error (Shu et al., 2024). Moreover, although some companies utilize specific software for quality control and planning, many systems do not fully guarantee compliance with regulatory standards, offering reports rather than ensuring precise execution of the design.

To address these challenges, the construction sector is increasingly incorporating digital technologies, such as laser scanners, BIM models, and machine learning (Wang; Kim, 2019; Shu et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2025). These technologies require significant initial investment, which may not be feasible for smaller firms (Lee; Nie; Han, 2023; Wang et al., 2025).

Recent studies have investigated the application of advanced technologies for inspecting structural elements of precast concrete. Li, Kim, and Lee (2021) developed a method to digitize reinforcement bars and classify their diameters using machine learning, validated in laboratory-produced slabs; however, it was not applied to precast elements in real-world conditions and relied on sophisticated equipment.

In another study, Shu et al. (2023) employed laser scanners to create point clouds and used deep learning for element segmentation, assessing elements post-concreting without examining reinforcement bars in the preliminary phase, beset by high costs. Ye et al. (2024) explored assembly analysis of precast elements using stereoscopic cameras and deep neural networks for positional analysis but did not address reinforcement bar positioning.

More recently, Wang et al. (2025) introduced a cost-effective 3D scanner using rotating 2D light detection and ranging, although it is limited to connection bars and does not inspect element interiors before concreting. This indicates a gap in developing accessible methods and tools for inspecting reinforcement bars in precast elements before concreting, particularly in actual contexts.

While research into precast element quality control before concreting has been increasing, particularly in the last five years, there remains a shortage of studies on the use of videogrammetry in industrial settings for inspecting reinforcement bars. The most relevant research, conducted by Han et al. (2013), aimed to develop an affordable technique for creating geometric models of reinforcement bars in a laboratory environment using a digital single-lens reflex camera in the red, green, and blue spectrum. However, this approach is limited by its controlled environment, which does not account for factors pertinent to real-world situations, such as the arrangement of elements, variations in lighting, and interference from surrounding

There is a significant gap in research on the inspection of precast reinforced concrete elements, especially in the early stages before concreting, that examines cost-effective tools and methods for assessing the quality of reinforcement bar assembly. Moreover, most existing studies have been carried out in controlled indoor settings. Hence, the importance of this study lies in its exploratory approach in real-world situations, employing more affordable tools than those used in previously cited research.

Application of videogrammetry for quality inspections of precast concrete reinforcement

Videogrammetry, also known as video-based photogrammetry, offers a significant advantage with faster data acquisition in the field (Murtiyoso; Grussenmeyer, 2021). Nonetheless, the quality of the outcomes hinges on the video quality and the sequence of frames extracted (Flies et al., 2019). Various strategies exist for recording objects of interest in videogrammetry. For static objects, a single video camera suffices, moving around the object to capture different angles. Conversely, for moving objects, utilizing more than two cameras is necessary to simultaneously capture the object from various locations. Another method involves rotating the object while keeping the camera stationary, typically mounted on a tripod (Groetelaars, 2015).

It is crucial to note that videogrammetry is grounded in photogrammetry’s principles, implying that both techniques depend on the same foundational principles for field data capture (e.g., photos, videos, or video frames) and utilize similar software for data processing, albeit with adaptations in certain steps or processes depending on the specific technique (Torresani; Remondino, 2019).

According to the fundamental recommendations of photogrammetry, particularly for automated restitution related to generating objects’ point clouds, capturing images around the object in a convergent manner from various angles (up to 15 degrees) with a high overlap of about 80% is recommended for optimal results (Groetelaars, 2015). Ensuring good lighting and image quality is paramount for capturing the object and its colors/textures with clarity.

Videos, serving as continuous records of objects, facilitate better image continuity and prevent gaps or significant angular shifts that may arise in photogrammetry. The capture speed plays a critical role during data acquisition; slower videos ensure greater overlap between sequential frames, albeit at the cost of increasing the volume of data requiring subsequent processing. However, this challenge can be addressed by decreasing the frame extraction rate per second (Murtiyoso; Grussenmeyer, 2021).

Today, several tools are available for the automated processing of photographs to generate point clouds, triangular irregular networks, orthophotos, and more. These tools include licenses that are either paid, such as Agisoft Metashape, PhotoModeler, Bentley ContextCapture, Autodesk Recap (offering educational licenses), 3DF Zephyr, and RealityCapture (featuring free versions with certain limitations), or free, including Colmap, Meshroom, MicMac, Regard3D, and VisualSFM. The processing steps in these tools vary, with some allowing direct video import and others requiring preliminary frame extraction using another program.

Despite the applicability of these techniques, only a handful of studies have explored videogrammetry and photogrammetry in supporting the quality control of rebar in precast concrete elements. Qureshi et al. (2022) evaluated 12 photogrammetry tools, accentuating 3DF Zephyr and Agisoft Metashape as the most efficacious in generating detailed 3D geometric models with minimal noise. Nevertheless, they noted limitations, including the need for scale adjustments and inconsistencies in model sizes across different tools, underscoring the need for testing in controlled environments.

Furthermore, Qureshi et al. (2022) deduced that the tools’ performance relies on the object type, task nature, and environmental conditions, with no consensus on the superiority of a specific tool. Advancing this research, Qureshi et al. (2024) introduced an automated rebar assessment model that integrates photogrammetry with MATLAB-developed algorithms for plane detection, noise removal, and rebar layer separation, facilitating the analysis of spacing, diameter, quantity, and length.

Despite this progress, the presented solutions require validation in real factory settings, where efficiency is crucial to manage the high volume of parts and the need for swift outcomes for concrete pouring within the constraints of the manufacturing environment. This gap signifies an opportunity for further research, focusing on the practical application of these technologies at an industrial scale.

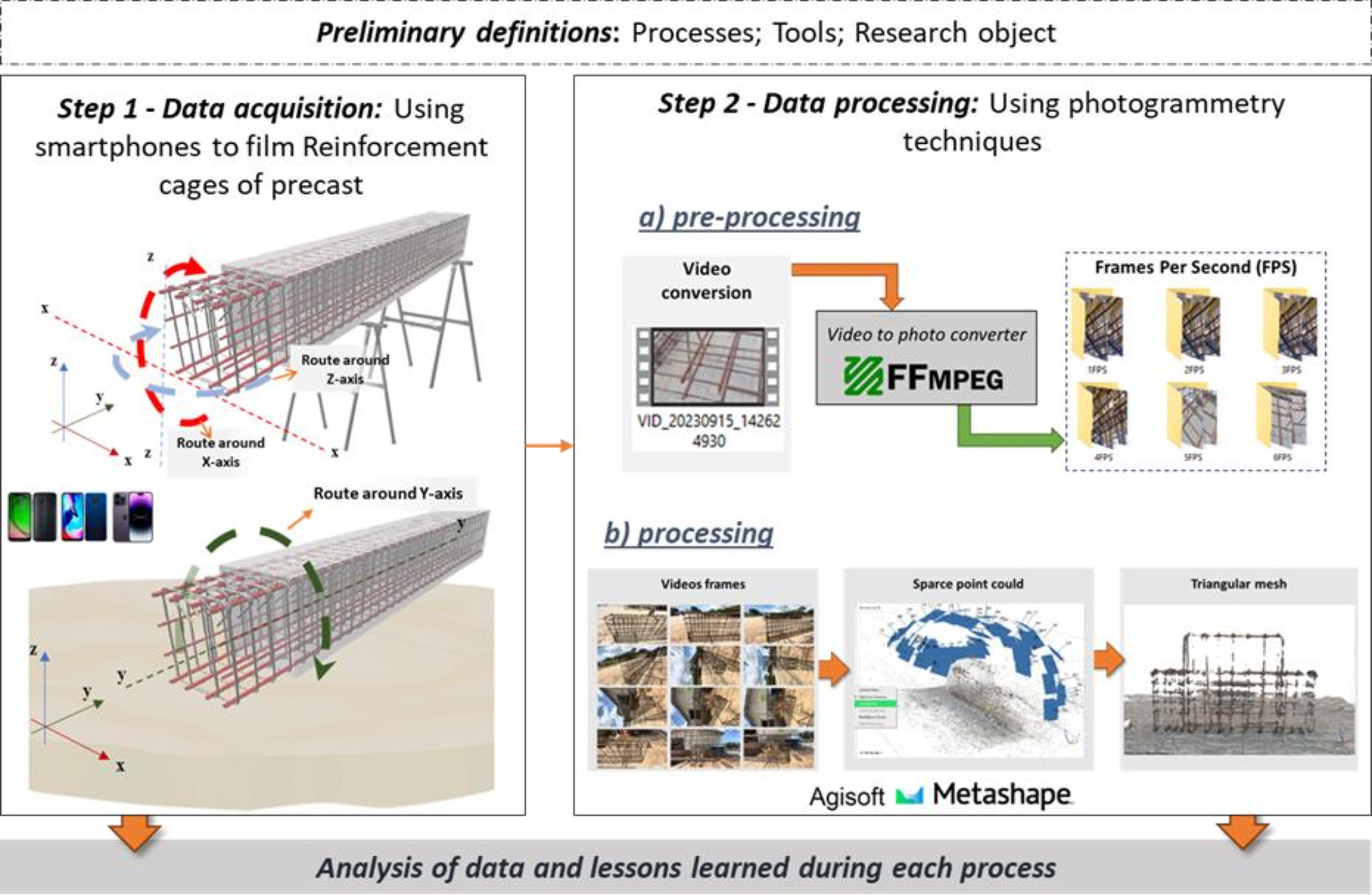

Methods

This investigation adopted a case study as its research strategy, which is preferable when addressing ‘how’ and ‘why’ research questions, specifically when the researcher has limited control over events and aims to understand a complex, contemporary phenomenon within a real-life context (Yin, 2013). Accordingly, the study sought to determine how videogrammetry methods and workflows utilizing videos captured on smartphones can support quality inspections of precast concrete in a manufacturing setting. The research was structured into three phases: gathering data on the reinforcement cages of precast concrete elements, processing the collected data using photogrammetry techniques, and analyzing the data (Figure 1).

The proposed technology was applied to objects without any intervention from the researchers, reflecting real-world conditions in the construction industry. To accomplish this, three visits were made to Factory X, a producer of precast concrete elements, and one visit to a medium-sized construction company where the elements were filmed. The items filmed were stored in the factory’s yard, encompassing various structural elements, including 10 beams, one foundation block, one column, and one set of cut and bent rebar.

In addition to selecting the pieces for study, the technologies for image acquisition and processing were chosen. The devices employed were smartphones of different models: Moto G7 Play, Moto E7 Plus, and iPhone 14 Pro Max (Figure 2). The Moto G7 Play features a 13-megapixel (MP) camera, records 4K video at a resolution of 3840 x 2160 pixels (Ultra HD) at 30 frames per second (FPS), and has an ƒ/2.0 aperture, a 28mm focal length, including digital video stabilization through software. The Moto E7 Plus, equipped with a dual-camera setup comprising a 2 MP depth lens and a 48 MP primary lens, records Full HD video at a resolution of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 60 FPS, features an f/1.7 aperture, and a 26mm focal length but lacks video stabilization. The iPhone 14 Pro Max is outfitted with a camera system that includes a 48 MP wide-angle lens (24mm focal length, ƒ/1.78 aperture), a 12 MP ultra-wide-angle lens (ƒ/2.2 aperture, 13mm focal length, 120° field of view), a 12 MP telephoto lens (77mm focal length, ƒ/2.8 aperture), and an additional 12 MP telephoto lens (48mm focal length, ƒ/1.78 aperture) with a quad-pixel sensor. This sophisticated system enables HDR Dolby Vision video recording up to 4K at 60 FPS and provides optical image stabilization for videos on wide-angle and telephoto lenses.

The selection of devices was influenced by the availability of technology within the research group and the objective to evaluate cost-effective solutions for videogrammetry. The smartphones were chosen based on their widespread availability in the market, their ability to capture images, and their potential for visual inspection applications using videogrammetry. This strategy aims to assess the suitability of common technologies, such as smartphones, for visual inspections, offering an affordable and readily implementable option in contrast to the high expenses associated with specialized equipment like terrestrial laser scanners. Moreover, the familiarity of operators, including interns and construction supervisors, with daily smartphone usage minimizes the necessity for extensive training, thereby facilitating the integration of this method into practical inspection scenarios. Table 1 provides the technical specifications of the smartphones utilized.

The data collected by these devices were processed using Agisoft Metashape, software capable of enabling automated photogrammetric restitution. This includes the generation of point clouds, irregular triangular meshes (textured or not), orthophotos, and more. Such data find applications across various aspects of civil engineering, including 3D modeling of buildings, inspections and monitoring of pathologies, topographic surveys, terrain analysis, construction documentation, quality control, project planning and logistics, building maintenance management, and interference and structural analysis (Agisoft, 2025).

In addition to Agisoft Metashape, the study utilized other software tools. Python, a versatile programming language widely adopted for data science and automation applications, was employed alongside FFMPEG, an open-source multimedia processing tool. This combination facilitated the sequential extraction of video frames, which were then processed in the photogrammetry software. LibreOffice Calc, a free spreadsheet software, was instrumental in analyzing and processing the obtained data. These tools were chosen for their free availability, ease of use, and suitability for the study’s specific requirements.

The data processing for this research was executed on a computer equipped with an Intel i7-6500U processor, operating at 2.50 GHz within a 64-bit architecture, a Nvidia GeForce 920MX graphics card with 2 GB of dedicated memory, and 8 GB of RAM.

Data acquisition

During the data acquisition phase, videos were recorded in the factory to capture the current state of the assembly process and parts inventory. The filming covered various locations throughout the factory, including inside the warehouses and outdoors, with parts stored on trestles and arranged on the factory floor being documented. No artificial lighting was employed during the filming. A summary of the parts acquired is presented in Table 2.

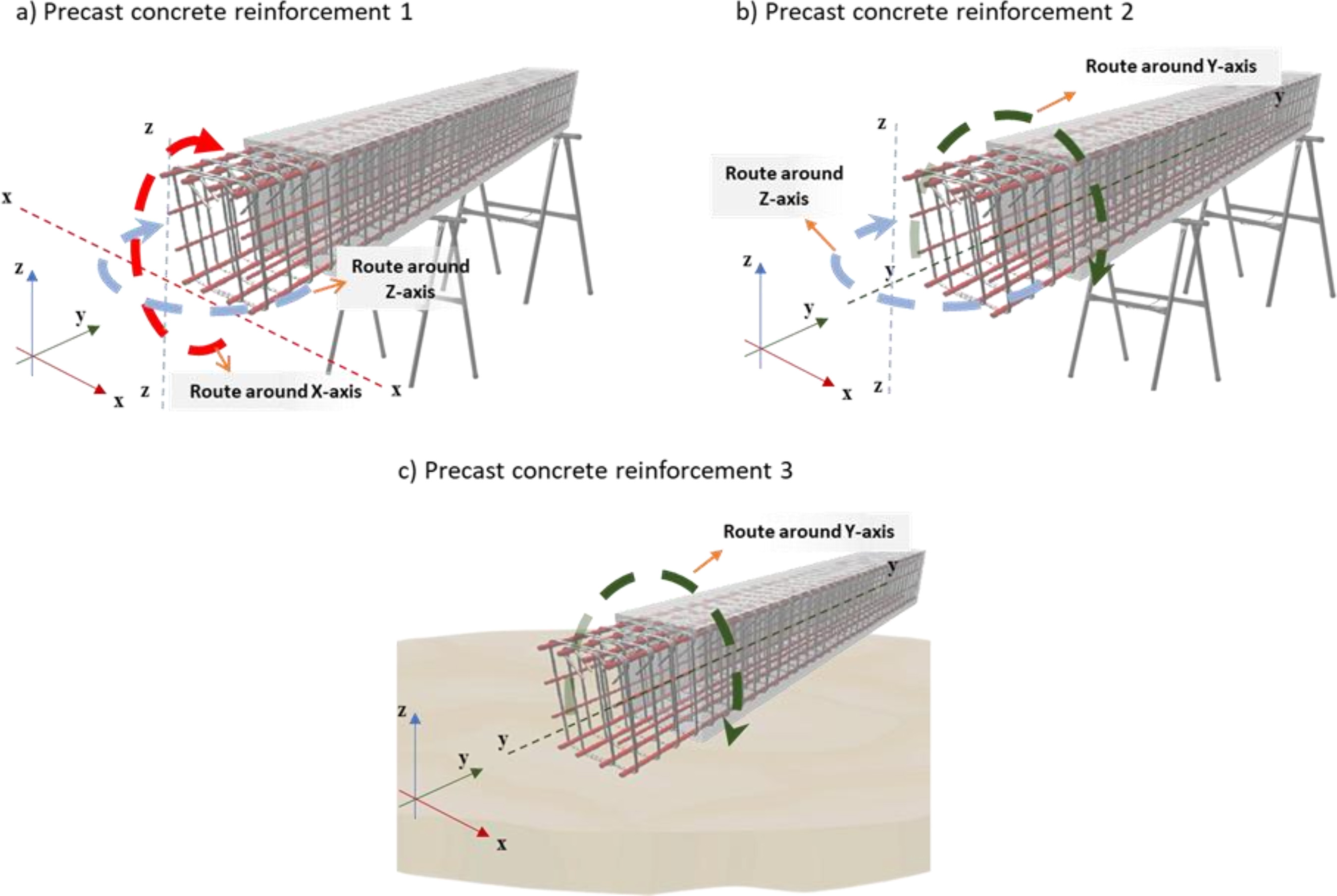

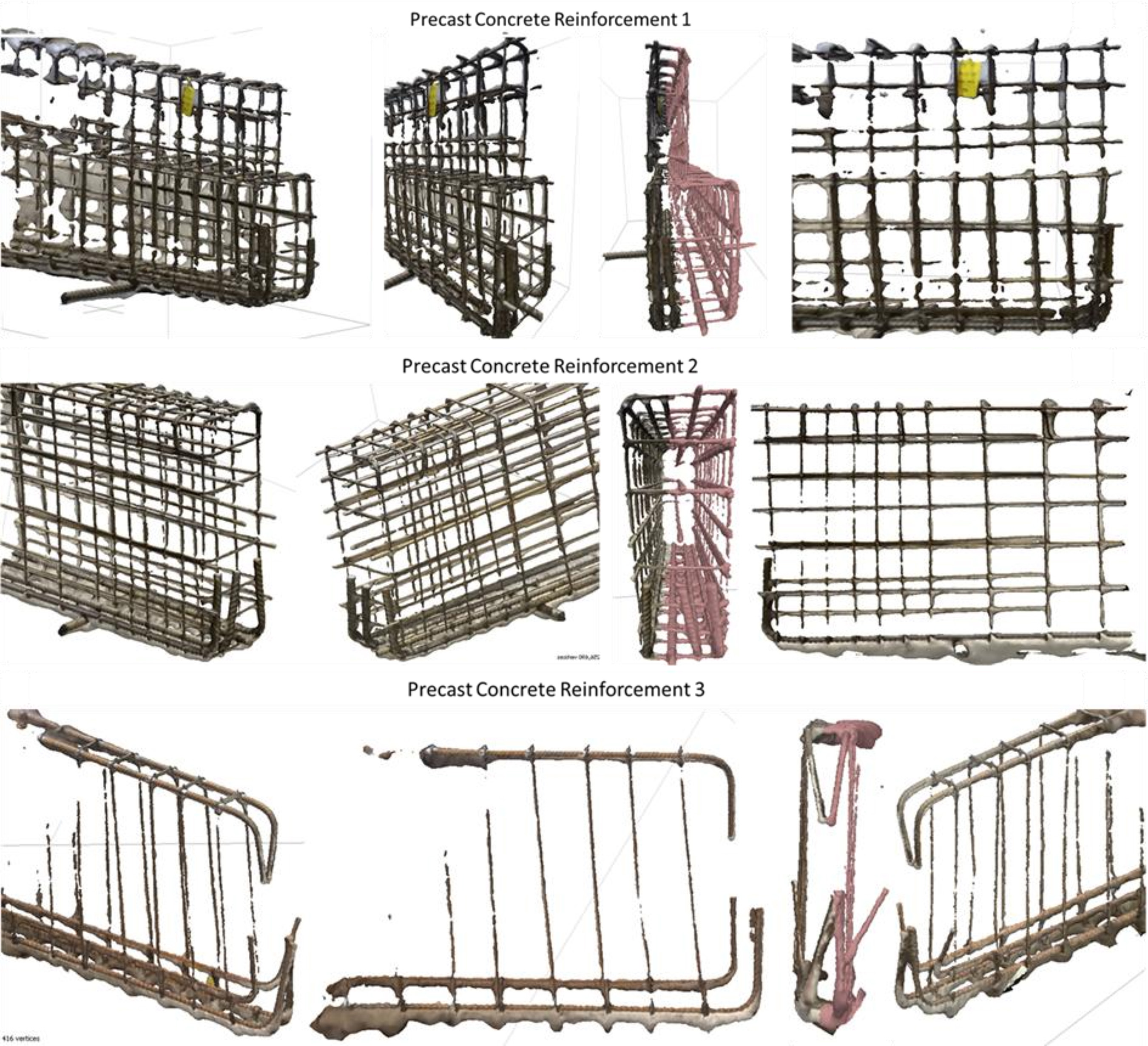

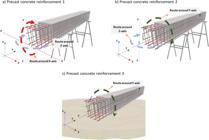

After conducting site visits and filming sessions, three sets of rebar, all made of steel and with diameters ranging from 6.3 to 12.5 millimeters, were selected for further analysis (Figure 3). The primary differences among these samples were attributed to their storage conditions and the lighting during the time of capture. Specifically, the rebar labeled precast concrete reinforcements (PCR) 1 and 2 were positioned on trestles in an open area, thus exposed to direct sunlight (Figures 3a and 3b). In contrast, the rebar designated as PCR3 was placed directly on the ground, shielded from direct sunlight (Figure 3c).

The three pieces selected for analysis yielded the most comprehensive and detailed models, effectively balancing processing time and quality. This approach facilitated the identification of rebar sets under varying storage and lighting conditions, which directly influenced the capture and processing of images. Consequently, the chosen pieces represented diverse scenarios, enhancing the evaluation of videogrammetry’s feasibility as a practical and efficient tool for supporting the quality management of precast elements.

The video acquisition of PCR was conducted along distinct trajectories to determine how these paths affect the construction of geometric models and identify factors contributing to the production of higher-resolution models. Figure 4a depicts the recording of PCR1 via a smartphone, with the piece mounted on trestles. The capture trajectory encompassed the X and Z axes, enabling the imaging of the structure’s front and side faces. In Figure 4b, the recording pursued a different route around the Y and Z axes, facilitating the capture of additional images of the piece’s top and sides. Figure 3c shows PCR3 positioned directly on the ground, with the trajectory encircling the Y-axis. This variation in the support base can affect the piece’s stability, lighting, and the quality of image capture.

All filming was conducted manually, without the support of any stabilization equipment or devices for automating the smartphone. Notably, it is important to highlight that the filming speed was not constant.

Data processing using photogrammetry techniques

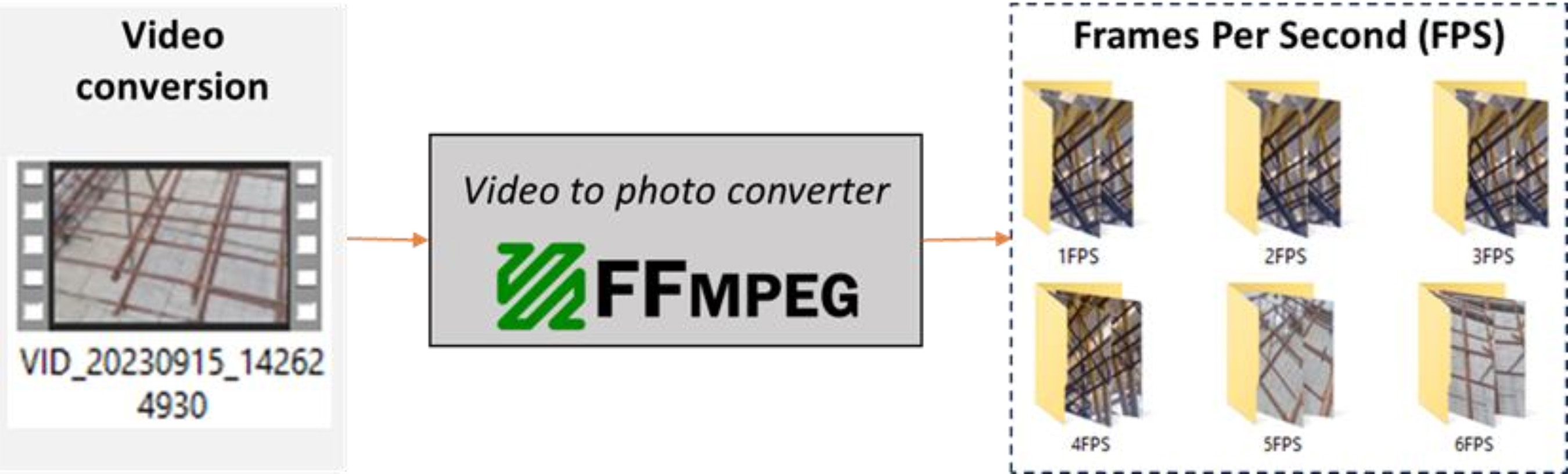

The image processing was divided into two main stages: pre-processing and processing. In the pre-processing stage, the captured videos were converted into photographs using the free tool FFMPEG, which supports various video formats (Figure 5). At this stage, different FPS settings were specified, influencing the number of photos processed by the photogrammetry software and affecting both the processing time and the quality of the final model. It is significant to mention that the total processing time also depends on the computer’s specifications used.

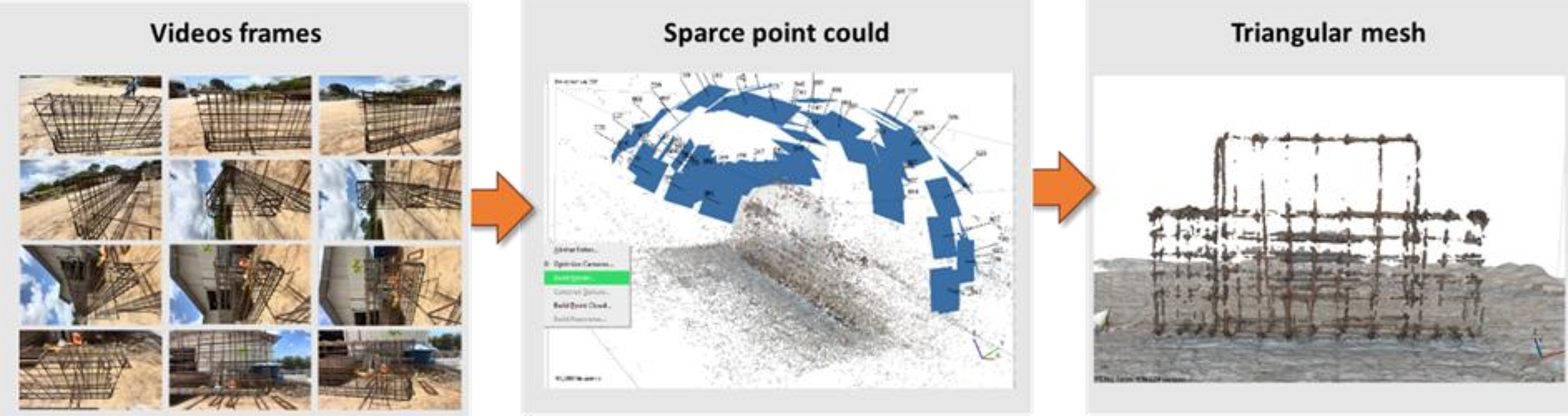

In the Metashape software, only two processes were utilized: ‘Align Photos’ to generate the sparse point cloud (or tie points) and ‘Build Model’ to create the irregular triangular mesh based on the depth map. The total processing time for each set of frames is the cumulative time to perform these two commands. The final models produced by these processes were then evaluated based on two criteria: the number of faces and the number of vertices (Figure 6).

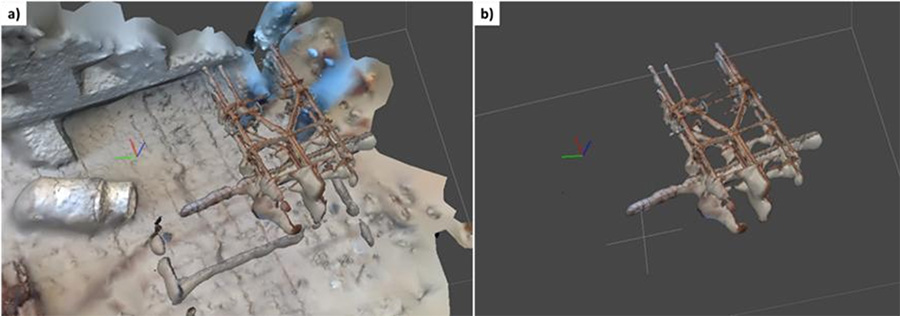

Although Metashape allows for additional processing steps, such as generating dense point clouds, vertex reduction (Decimate Modifier), creating photorealistic textures, and applying gradual selection filtering, these features necessitate additional procedures and/or individual model manipulation. It is noteworthy that for the evaluation of face and vertex counts, triangular meshes were trimmed (using the Metashape cutting tool) to eliminate digitally reconstructed elements not pertinent to the studies (Figure 7).

Results

This section presents the principal findings regarding the proposal and analysis of indicators for image processing, alongside the lessons learned from acquiring and processing the images utilized in the research.

Proposition and analysis of indicators for image processing

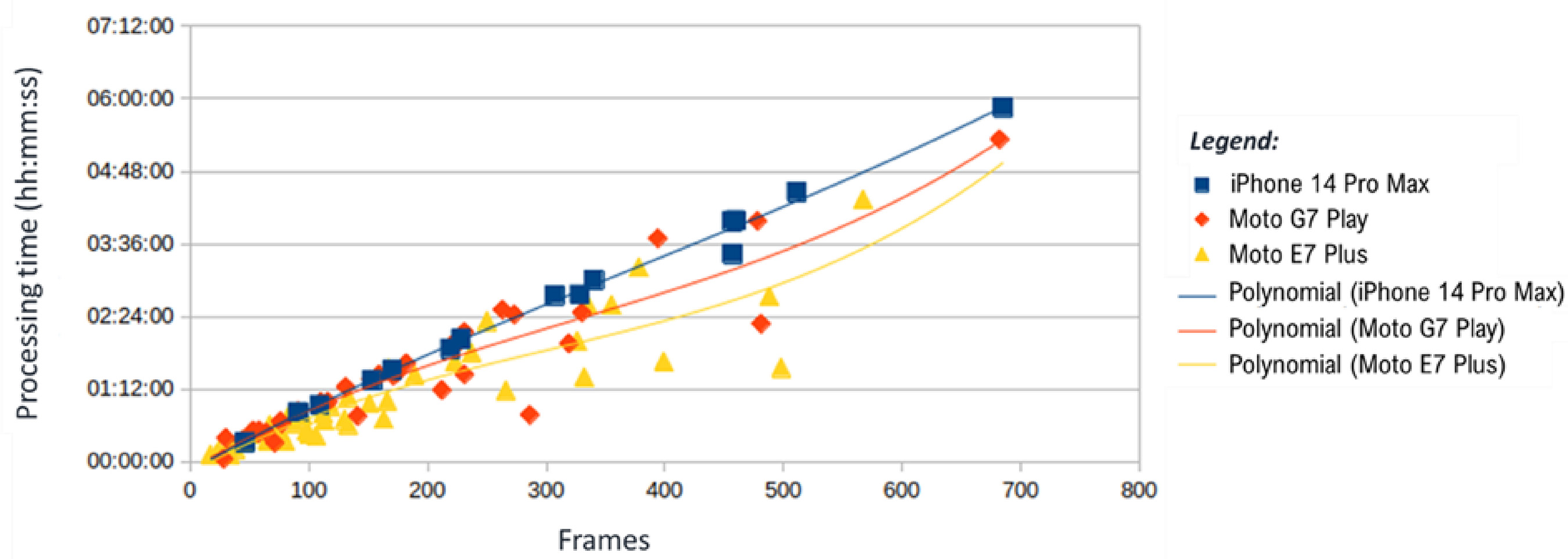

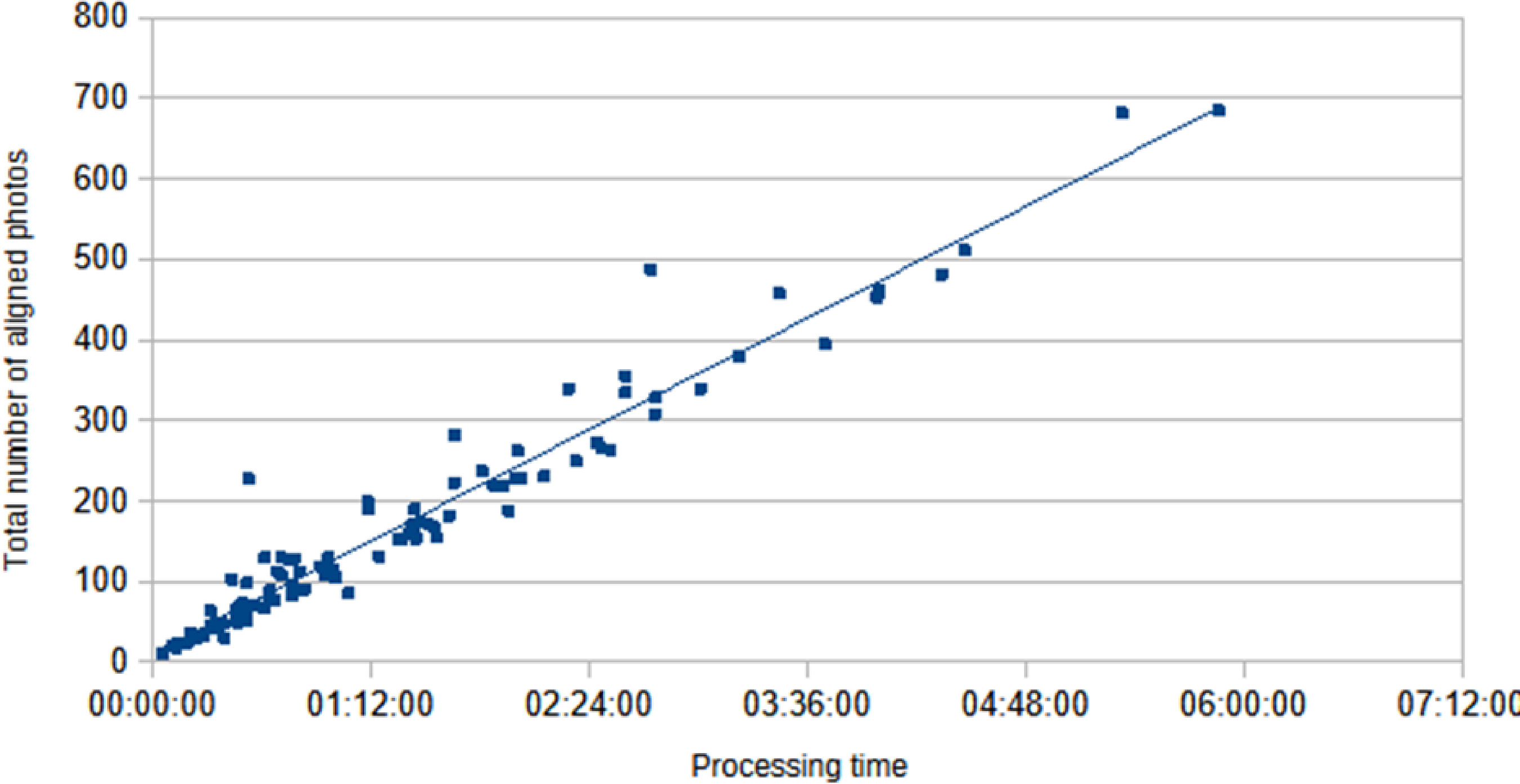

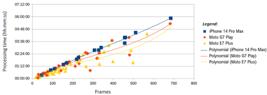

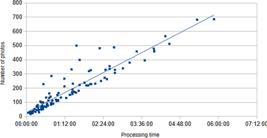

Initially, an investigation was conducted to determine whether changing the smartphone model would significantly impact processing time. The authors created a graph to evaluate the relationship between time spent and the number of photos (Figure 8), organizing the data by device model and adding trend lines to facilitate analysis.

Figure 8 illustrates that processing time varies depending on the smartphone model used to capture images. Testing revealed that when processing more than 200 frames, only the iPhone 14 Pro Max exhibited linear behavior, whereas the other two models demonstrated significant variance in processing time. This variation, albeit slight, likely results from the different resolutions of frames extracted from each smartphone’s videos, directly affecting the volume of information processed and, consequently, the reliability of future processing time estimates. The discrepancy among the results can be attributed to the distinct stabilization technologies present in each device.

Thus, it can be concluded that the iPhone 14 Pro Max, with its 48MP camera, can record videos at a resolution of 3840x2160 pixels and produces the sharpest images, with high resolution and a substantial volume of information per pixel. Consequently, this device required the longest processing time per image. Despite this, the model stood out for its consistency, attributable to its onboard optical stabilization technology. Despite being a simpler model than the Moto E7 Plus, the Moto G7 Play captures videos at the same resolution as the iPhone 14 Pro Max (3840x2160 pixels). Although the resolution is identical, photo processing with the Moto G7 Play is faster than with the iPhone 14 Pro Max. However, the Moto G7 Play’s digital stabilization system is less efficient than the optical stabilization system of the iPhone 14 Pro Max, resulting in greater variability in the Moto G7 Play’s results. Among the tested devices, the Moto E7 Plus has the lowest resolution, at 1920x1080 pixels, hence the frames were processed more rapidly.

Beyond visual analysis, video processing from site visits yielded valuable data. The researchers developed three key indicators to support the achievement of research goals. These indicators aid in defining and interpreting the processing parameters used to create geometric models of the rebar from the captured images.

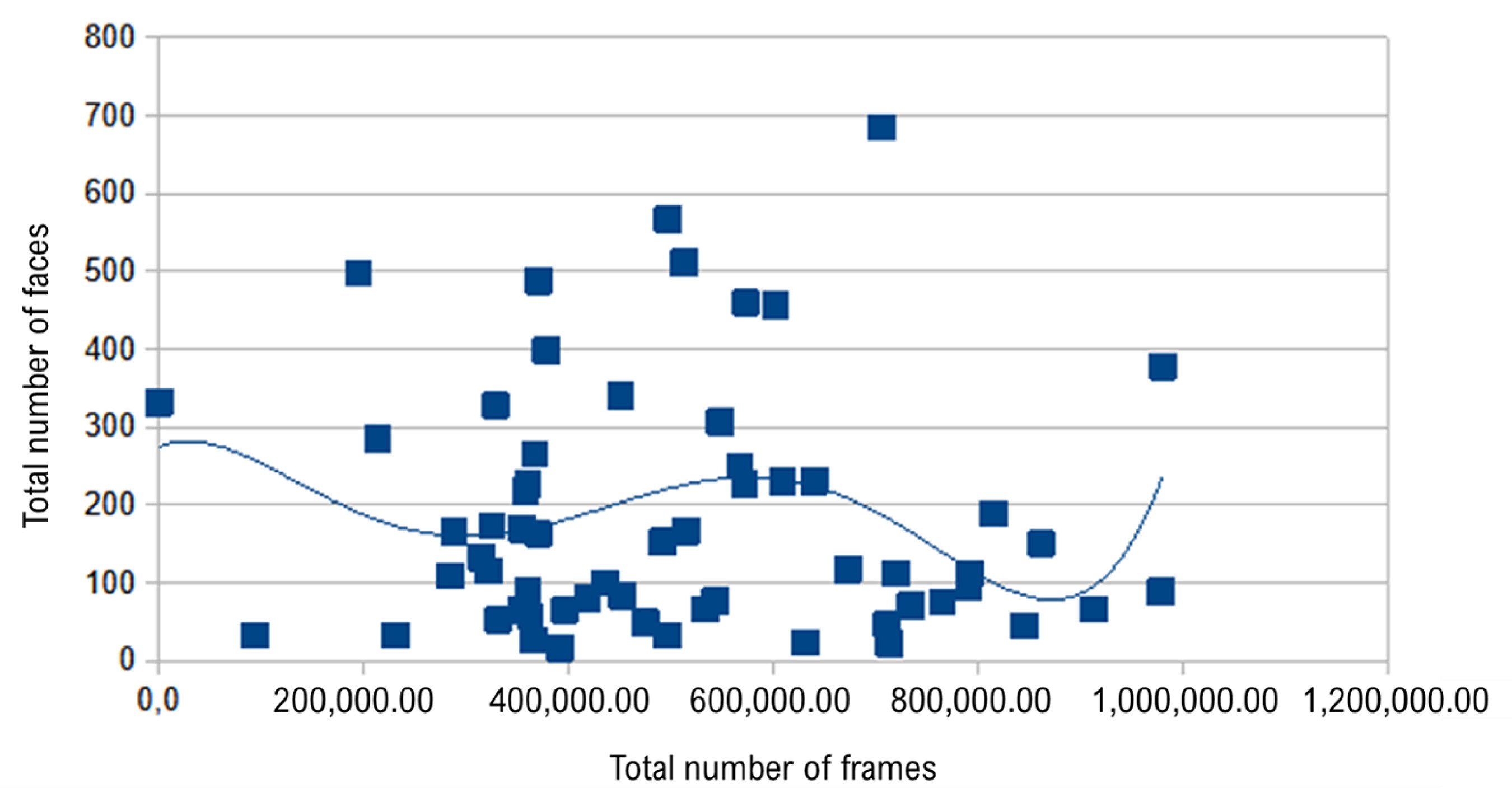

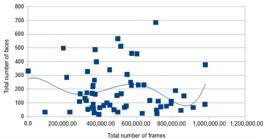

The first indicator, ‘Return,’ measures the relationship between the number of video frames used for processing and the resulting complexity of the 3D rebar model in Metashape (specifically, the number of faces in its triangular mesh). This indicator is crucial as it reveals how processing efficiency is influenced by more than just the photo count. As demonstrated in Figure 9, the wide variation in return values suggests that processing efficiency is affected by several factors beyond photo count. Therefore, additional factors must be considered during processing. Several factors, including lighting conditions, the texture uniformity of photographed elements, and the speed of video movement, can influence the information captured in point clouds or triangular meshes. These factors affect image overlap and the volume of data processed. Objects with well-defined textures and geometries, facilitating better frame-to-frame correlation, typically yield denser and more complete geometric models.

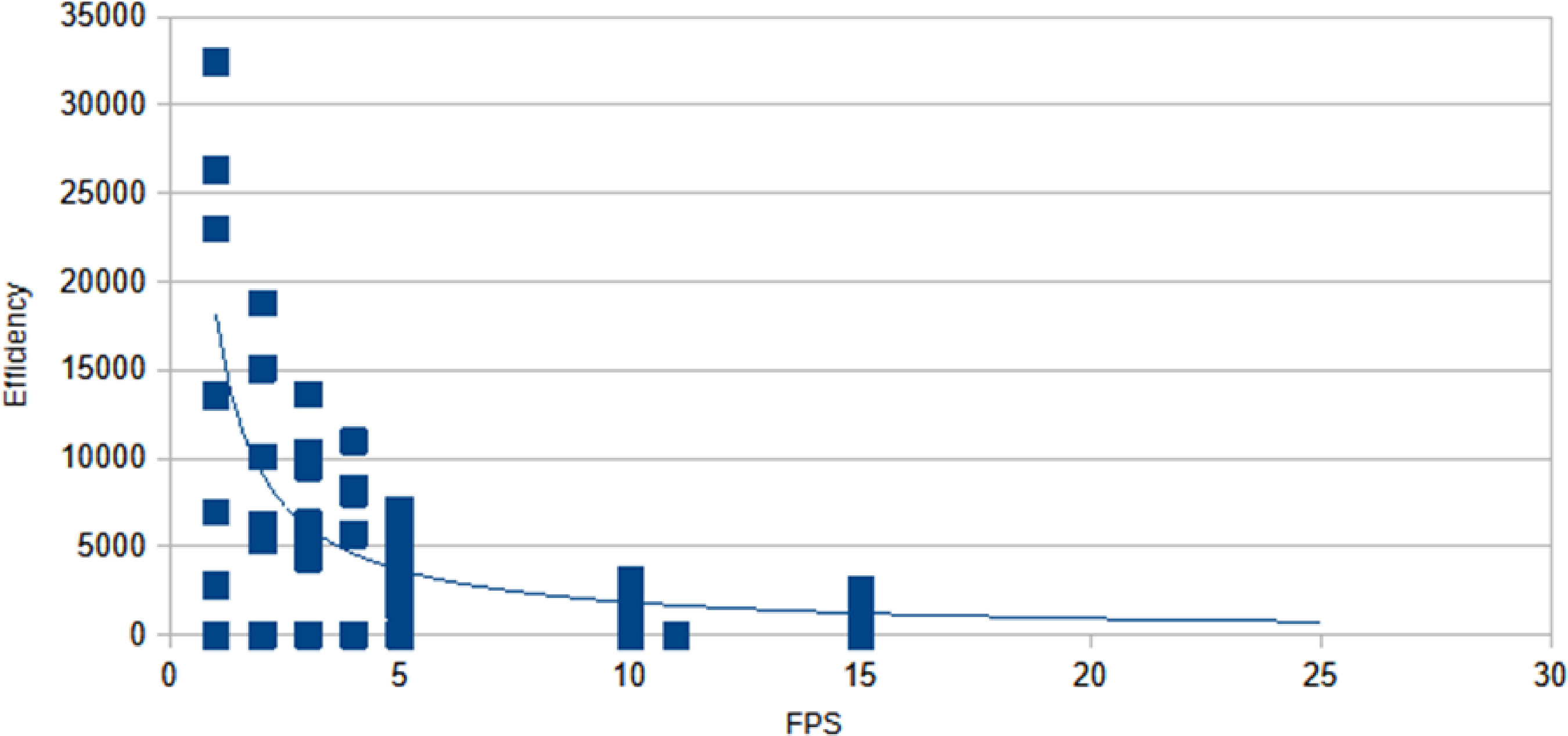

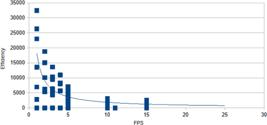

The second indicator, ‘Efficiency,’ measures the relationship between the number of faces in the generated 3D mesh and the number of video frames used in the photogrammetric process (Figure 10), specifically relating to the frame rate (FPS) extracted from the original video. This indicator underscores the importance of an inverse relationship between efficiency and FPS. A higher frame rate thus increases the processing load but does not necessarily enhance the quality of the resulting geometric model. This insight is fundamental for optimizing processing parameters to create high-quality geometric models of the rebar from captured images. In essence, a balance between the number of faces in the 3D mesh and the FPS must be achieved to ensure the most efficient processing without compromising model quality.

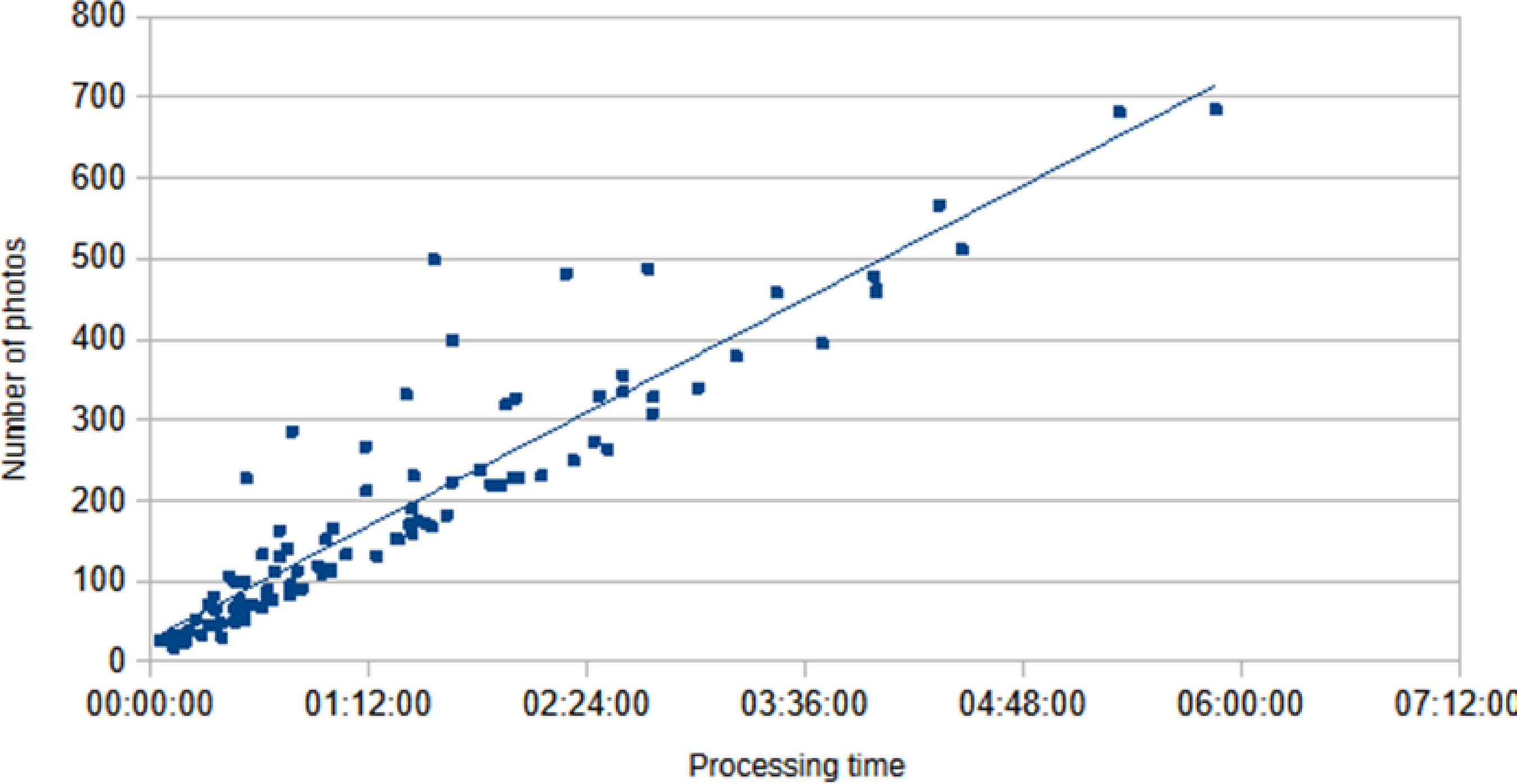

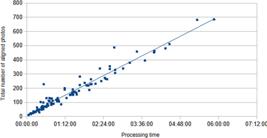

Analysis of Figure 10 reveals several key insights into processing behavior, indicating that lower FPS generally led to more efficient processing than higher FPS. However, while lower FPS typically enhances efficiency, certain models with low FPS still exhibit poor performance. This suggests that other factors, such as lighting (including shadows), background color, and camera movement speed, also play significant roles in determining processing efficiency. Moreover, the ‘Cost’ indicator, which tracks the computational expense – specifically, the processing time required for a specific number of images (Figure 11) – is critical for budgeting and resource allocation in projects managing large image datasets, offering a precise measure of processing time needed for a set quantity of images.

Figure 11 illustrates significant deviation from the trend line at approximately the 500-photo mark, where processing times vary widely, with some models taking 01:33:23 and others 04:27:49. Further examination revealed that this variability arises because Figure 11 considers the total number of photos rather than just the aligned ones. Given that non-aligned photos bypass subsequent photogrammetry processes, they should be excluded from comparisons of processing time to photo count. To address this, we generated a new graph (Figure 12) focusing solely on the aligned photos. Notably, image alignment issues predominantly occur with significant lighting changes and poor image quality, often due to autofocus failures in unstable or inconsistent recordings.

The analysis of the correlation between the indicators and the test outcomes facilitates the estimation of optimal parameters for capturing and processing data via photogrammetry. For video capture, we recommend a minimum duration of 30 seconds, as lower FPS and longer videos correlate with heightened processing efficiency. Nonetheless, to contain computational expenses, we propose capping video length at 180 seconds (3 minutes). This study’s analysis of the ‘Efficiency’ indicator suggests that the ideal FPS for optimizing processing ranges between 1 and 5.

To implement the research findings, we developed two functions predicting video processing time. Users can input the video’s length in seconds and the desired FPS for preprocessing. A straightforward calculation – FPS multiplied by video length – yields the total number of frames. The second function estimates the total processing time based on the relationship between the number of frames and processing time.

Lessons learned for image acquisition

This subsection presents what worked and what did not in data acquisition.

What worked well?

Overall, geometric models of reinforcement filmed on trestles demonstrated superior results compared to those where the reinforcement was placed directly on the ground. Complex routes did not hinder the generation of geometric models.

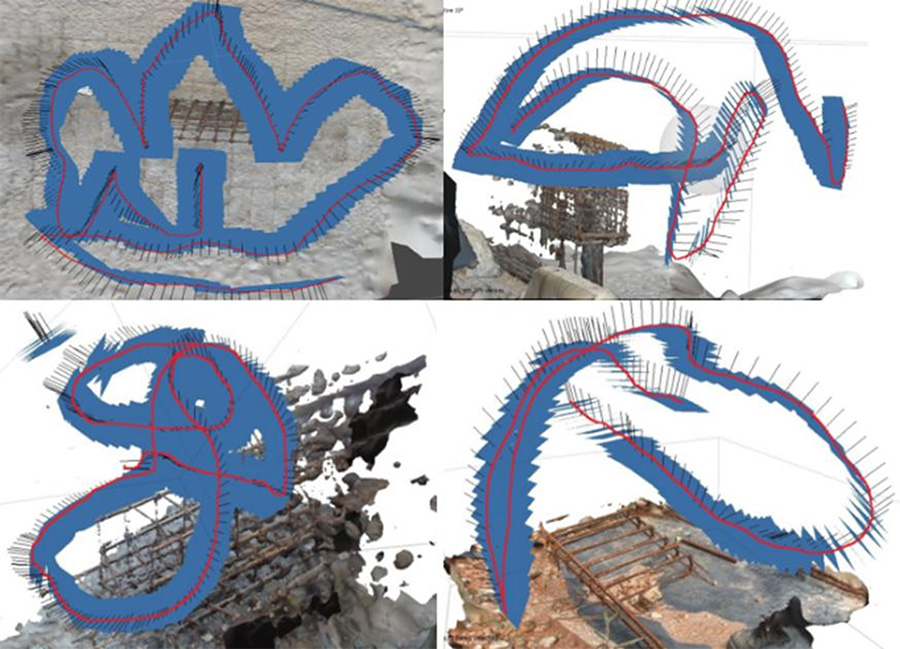

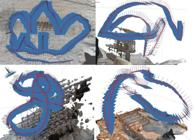

Initially, the plan was to capture videos in a standardized manner, requiring the operator to maintain a constant speed and distance from the target, following pre-planned orbits. However, given the exploratory nature of this study, we experimented with a greater degree of freedom in some videos, resulting in complex routes. Surprisingly, Agisoft Metashape efficiently tracked and processed these complex routes, as illustrated in Figure 13, using the software’s ‘Camera’ feature.

What did not work well?

Sudden and drastic variations in brightness caused the photos to lose alignment. Splitting the video sequentially, using Python and FFmpeg, proved faster than employing Agisoft. To illustrate, processing a 33-second video took over 20 minutes with the software compared to just 35 seconds with FFmpeg and Python.

Lessons learned for image processing

This subsection presents what worked and what did not in data processing.

What worked well?

Adjusting the ‘Accuracy’ settings during photo alignment can prevent gaps in the geometric model. Upon varying the settings of the ‘Align Photos’ step while keeping the others constant, it was observed that enhancing the ‘Precision’ setting could avert discontinuities in the geometric model.

Enhancing the ‘Quality’ and ‘Face Count’ settings notably improves the visibility of details, such as the wire binding in a reinforcement cage. This was evident upon varying the settings in the ‘Generate Model’ step and maintaining consistency across other parameters, leading to a discernible improvement in the model’s texture quality. This, at times, allowed the visualization of wire ties.

What did not work well?

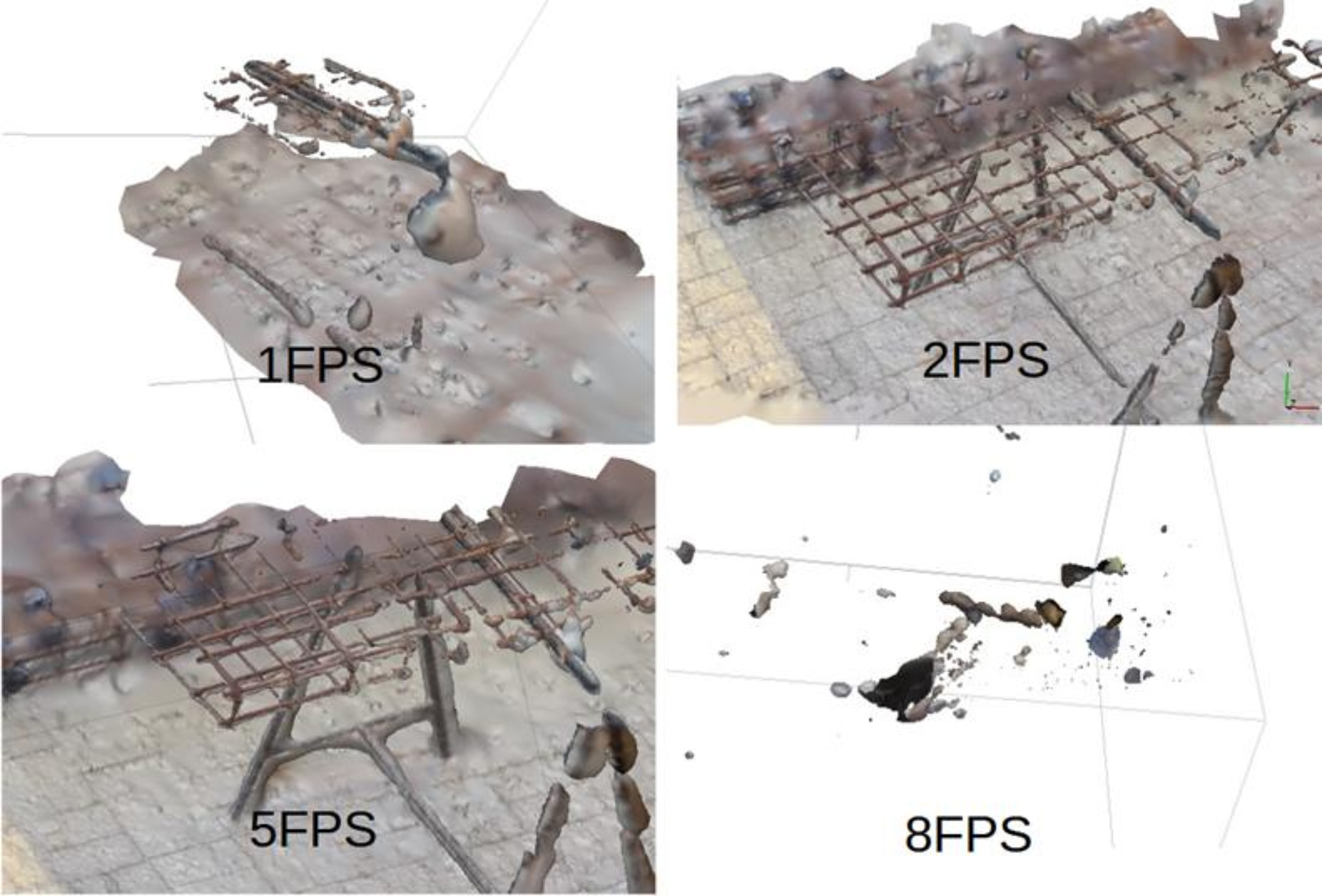

High FPS can create challenges for image alignment. Notably, image alignment may be compromised by high frame rates under certain conditions, resulting in models with significant flaws. Figure 14 shows the correlation between the FPS rate and model quality.

Figure 15 shows the optimum outcomes achieved using the videogrammetry technique. These geometric models effectively validate the alignment of the assembled reinforcement with the design specifications. Success in these instances can be attributed to three pivotal factors: The models were generated at 3 FPS, the videos featured reinforcements positioned on a metal support, and the researchers leveraged insights gained from previous capture sessions.

Conclusions

This study explored videogrammetry’s application in generating geometric models of precast concrete reinforcement, aiding quality inspection activities before concreting in a manufacturing setting. The research evaluated computational processing time and model quality, alongside the efficacy of mobile devices and videogrammetry as cost-effective quality management tools. Smartphones have emerged as economical alternatives to more costly technologies, such as laser scanners, for capturing images and videos.

The results revealed that to achieve satisfactory reinforcement models, certain conditions must be met. The efficiency of the model generation process is influenced by factors including adequate lighting, the operator’s movement speed, and the settings for frame extraction intervals. If the frames are spaced too widely, they can diminish the necessary overlap, while overly brief intervals may increase processing time without enhancing the model’s quality. Hence, it is crucial to select the extraction interval meticulously and maintain consistent speed during capture to ensure the technique’s success.

Moreover, image quality can suffer from camera shake or lack of focus, issues more prevalent in video recordings than in the static photos used in traditional photogrammetry. These problems can affect the accuracy of geometric models, underscoring the importance of balancing acquisition speed and file size. Although smartphones represent a practical and cost-effective solution, achieving high-quality results necessitates proper control over capture parameters, such as lighting and stabilization.

Despite the promising outcomes of this study and the insights gained from the experiments, further research is essential to systematically integrate this technique into the construction industry. Future investigations could focus on using targets to mark control points with known coordinates, aiding in determining the geometric model’s real scale and rotation. This approach could support or enhance the image alignment process, additionally enabling verification of the reinforcement’s accuracy by comparison with design-stage models.

Future studies might also examine the impacts of variables like lighting and shadows, background color, and operator movement speed on videogrammetry results. Through refining workflows and verifying model precision, videogrammetry could solidify its status as a low-cost, high-efficiency tool for quality management in precast concrete manufacturing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq) for awarding an undergraduate scholarship to the sixth author (Process 407932/2022-4) and a graduate scholarship to the first author. We would also like to thank the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – CAPES) for granting a graduate scholarship to the third author. Additionally, we extend our appreciation to the company that provided the data used in this study.

References

-

AGISOFT. Agisoft Metashape Professional Edition: software de fotogrametria. Versão 2.2.1. São Petersburgo: Agisoft, 2025. Available: https://www.agisoft.com/ Access: May 6, 2025.

» https://www.agisoft.com/ - ARAÚJO, B. K. R.; SILVA, A. S.; MELO, R. S. S. Method of automated inspection for reinforcement cages of precast concrete elements. PARC: Pesquisa em Arquitetura e Construção, v. 15, p. e024021, 2024.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NBR 14931: execução de estruturas de concreto armado, protendido e com fibras: requisitos. Rio de Janeiro, 2023b.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NBR 6118: projeto de estruturas de concreto. Rio de Janeiro, 2023a.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS. NBR 9062: projeto e execução de estruturas de concreto pré-moldado. Rio de Janeiro, 2017.

- FLIES, M. J. et al. Forensic 3D documentation of skin injuries using photogrammetry: photographs vs video and manual vs automatic measurements. International Journal of Legal Medicine, v. 133, n. 3, p. 963-971, 2019.

- GROETELAARS, N. J. Criação de modelos BIM a partir de “nuvens de pontos”: estudo de métodos e técnicas para documentação arquitetônica. Salvador, 2015. 372 f. Tese (Doutorado em Arquitetura e Urbanismo) - Faculdade de Arquitetura, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, 2015.

- HAN, K. et al Vision-based field inspection of concrete reinforcing bars. In: DAWOOD, N.; KASSEM, M. (Eds.). In: INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CONSTRUCTION APPLICATIONS OF VIRTUAL REALITY, 13., London, 2013. Proceedings […] London, 2013.

- KIM, M.; THEDJA, J. P. P.; WANG, Q. Automated dimensional quality assessment for formwork and rebar of reinforced concrete components using 3D point cloud data. Automation in Construction, v. 112, p. 103077, 2020.

- LEE, D.; NIE, G.; HAN, K. Vision-based inspection of prefabricated components using camera poses: Addressing inherent limitations of image-based 3D reconstruction. Journal of Building Engineering, v. 64, p. 105710, 2023.

- LI, C. Z. et al. The application of advanced information technologies in civil infrastructure construction and maintenance. Sustainability, 14, 7761, 2022.

- LI, F.; KIM, M.; LEE, D. Geometrical model-based scan planning approach for the classification of rebar diameters. Automation in Construction, v. 130, p. 103848, 2021.

- LIU, X. et al Videogrammetric technique for three-dimensional structural progressive collapse measurement. Measurement, v. 63, p. 87-99, 2015.

-

MAGAZINE LUIZA. Celulares e smartphones Available: https://www.magazineluiza.com.br/celulares-e-smartphones/l/te/ Access: 15 nov. 2024.

» https://www.magazineluiza.com.br/celulares-e-smartphones/l/te/ - MURTIYOSO, A.; GRUSSENMEYER, P. Experiments using smartphone-based videogrammetry for low-cost cultural heritage documentation. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, v. 46, p. 487-491, 2021.

- PAUKKONEN, N. Towards a mobile 3D documentation solution: video-based photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as fieldwork documentation tools. Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology, v. 6, n. 1, p. 143-154, 2023.

- PETERSON, S.; LOPEZ, J.; MUNJY, R. Comparison of UAV imagery-derived point cloud to terrestrial laser scanner point cloud. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, v. 4, p. 149-155, 2019.

- QURESHI, A. H. et al. Comparison of photogrammetry tools considering rebar progress recognition. XXIV ISPRS Congress, v. 43, p. 6-11, 2022. Referenciar conforme abnt

- QURESHI, A. H. et al. Smart rebar progress monitoring using 3D point cloud model. Expert Systems with Applications, v. 249, p. 123562, 2024.

- SHU, J. et al. Point cloud and machine learning-based automated recognition and measurement of corrugated pipes and rebars for large precast concrete beams. Automation in Construction, v. 165, p. 105493, 2024.

- SHU, J. et al. Point cloud-based dimensional quality assessment of precast concrete components using deep learning. Journal of Building Engineering, v. 70, p. 106391, 2023.

- SILVA, A. S. et al. CNN-based model for automated anomaly recognition in façade execution to support Quality Management. Ambiente Construído, Porto Alegre. 2025 (In press). Referenciar conforme abnt

- SILVA, A. S.; COSTA, D. B. Análise do uso de tecnologias digitais para identificação automatizada de patologias em construções. In: ENCONTRO NACIONAL DE TECNOLOGIA DO AMBIENTE CONSTRUÍDO, 19., Porto Alegre, 2022. Anais [...] Porto Alegre: ANTAC, 2022.

- SUN, Z.; ZHANG, Y. Using drones and 3D modeling to survey Tibetan architectural heritage: a case study with the multi-door stupa. Sustainability, v. 10, n. 7, p. 2259, 2018.

- TANG, P. et al. Automatic reconstruction of as-built building information models from laser-scanned point clouds: A review of related techniques. Automation in construction, v. 19, n. 7, p. 829-843, 2010.

- TORRESANI, A.; REMONDINO, F. Videogrammetry vs photogrammetry for heritage 3D reconstruction. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci., XLII-2/W15. 2019. p. 1157-1162. Referenciar conforme abnt

- WANG, D. et al. Automated recognition and rebar dimensional assessment of prefabricated bridge components from low-cost 3D laser scanner. Measurement, v. 242, p. 115765, 2025.

- WANG, Q.; CHENG, J. C. P.; SOHN, H. Automated estimation of reinforced precast concrete rebar positions using colored laser scan data. Computer‐Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering, v. 32, n. 9, p. 787-802, 2017.

- WANG, Q.; KIM, M. K. Applications of 3D point cloud data in the construction industry: a fifteen-year review from 2004 to 2018. Advanced engineering informatics, v. 39, p. 306-319, 2019.

- WANG, Q.; TAN, Y.; MEI, Z. Computational methods of acquisition and processing of 3D point cloud data for construction applications. Archives of computational methods in engineering, v. 27, n. 2, p. 479-499, 2020.

- WU, K. et al Automated quality inspection of formwork systems using 3D point cloud data. Buildings, v. 14, n. 4, p. 1177, 2024.

- YE, X. et al computer vision-based approach to automatically extracting the aligning information of precast structural components. Automation in Construction, v. 164, p. 105478, 2024.

- YIN, R. K. Case study research: design and methods. New York: Sage, 2013.

- YUAN, X. et al. Automatic evaluation of rebar spacing using LiDAR data. Automation in Construction, v. 131, p. 103890, 2021.

Edited by

-

Editor:

Enedir Ghisi

-

Editora de seção:

Luciani Somensi Lorenzi

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

16 June 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

31 Jan 2025 -

Accepted

10 Apr 2025

Lessons from the use of videogrammetry for quality inspections of precast concrete reinforcement

Lessons from the use of videogrammetry for quality inspections of precast concrete reinforcement

Source:

Source: