Abstract

Modular construction consists of the prefabrication of modules in controlled environments which are assembled in construction sites. The design process is crucial for the timely definition of modular components. This study aims to devise a collaborative planning and control model to improve the design process in modular construction companies, addressing project complexity and stage integration. The Design Science Research (DSR) approach was adopted, and two empirical studies were conducted in different projects. The model is grounded in the Last Planner System (LPS), being supported by collaborative practices and visual management tools. The results indicated that the model enhanced information exchange, transparency, and shared commitment. Furthermore, the implementation of collaborative meetings, supported by visual tools, improved integration among internal and external design team members, helping reduce inconsistencies and delays in the design process.

Keywords

Modular construction; Design management; Last Planner System; Collaboration; Planning and control

Resumo

A construção modular consiste na pré-fabricação de módulos em ambientes controlados que são montados em canteiros de obra. O processo de projeto é fundamental para a definição rápida dos componentes modulares. Este estudo tem como objetivo desenvolver um modelo colaborativo de planejamento e controle para aprimorar o processo de projeto em empresas de construção modular, considerando a complexidade do projeto e a integração de etapas. A abordagem DSR foi adotada, e dois estudos empíricos foram conduzidos em diferentes projetos. Dois estudos empíricos foram realizados em diferentes empreendimentos da empresa. O modelo é fundamentado nos princípios do Last Planner System, sendo apoiado por práticas colaborativas e ferramentas de gestão visual. Os resultados indicaram que o modelo melhorou a troca de informações, a transparência e o comprometimento compartilhado. Além disso, a implementação de reuniões colaborativas, apoiadas por ferramentas visuais, aprimorou a integração entre membros internos e externos da equipe de projeto, contribuindo para a redução de inconsistências e atrasos no processo de projeto.

Palavras-chave

Construção modular; Gestão do projeto; Last Planner System; Colaboração; Planejamento e controle

Introduction

Modular Construction (MC) differs from traditional construction, mainly for using modules manufactured in controlled environments and transported for assembly in construction sites (Innella; Arashpour; Bai, 2019; Olawumi et al., 2022). Although industrialized construction has the potential to reduce the complexity of on-site activities, it can introduce new complexity factors at other levels, as a higher degree of interdependency is necessary between different operations units, i.e., design, manufacturing, logistics, and site assembly (Bataglin; Viana; Formoso, 2022). Moreover, MC projects often involve additional activities that do not involve modular components, being necessary to integrate the assembly of highly industrialized components with traditional on-site activities.

The production flow of MC companies can be divided into five main stages (Innella; Arashpour; Bai, 2019):

-

design;

-

material and component supply;

-

manufacturing;

-

logistics; and

-

site assembly.

These stages are interdependent and generate mutual impacts, making proper integration and coordination among them essential for the success of a MC project (Innella; Arashpour; Bai, 2019).

This study is focused on the management of the design stage of MC projects, as it plays a crucial role in generating key information for subsequent activities, clearly defining the components that need to be produced and assembled. Furthermore, the design process in MC companies has the unique characteristic that each design must consider two types of operations requirements: some concerned with manufacturing processes and others with site installation. This requires careful integration of manufacturing, logistics, and site assembly processes (Molavi; Barral, 2016; Wesz; Formoso; Tzortzopoulos, 2018; Innella; Arashpour; Bai, 2019). Design is particularly critical in MC due to the short project lead time, as well as the need to customize products for specific projects due to the diversity of requirements among different customers or client organizations. Moreover, the design process often plays a coordinating role among other processes, as it strongly impacts time deadlines and cost targets. In other words, poor decisions made during the design process can negatively impact the entire lifecycle of MC products (Mounla et al., 2023).

Therefore, MC companies must devise effective planning and control systems for managing the design process in a context that is often highly complex and involves a wide range of activities that must be carried out in parallel due to short lead times. The Lean Production philosophy has been pointed out as a suitable approach for environments characterized by high variability and complexity, as it is the case of the design process in MC. Originally developed for the car industry, this philosophy has been adapted to construction for over three decades (Chiu; Cousins, 2020; Shehab et al., 2023). The Last Planner System® (LPS), initially devised by Ballard and Howell (1998), is a planning and control approach that has been successfully implemented in a large number of companies from several countries (Olivieri et al., 2019; Elfving, 2022; Hamerski et al., 2024). It is a hierarchical, collaborative planning and control model whose success is believed to stem from its principles and practices that match the complex nature of construction projects (Ballard; Tommelein, 2021).

In LPS, plans are collaboratively developed by creating an environment in which participants make explicit commitments (Fundli; Drevland, 2014). Recent studies have analyzed the use of LPS in the design process, proposing improvements on how to manage design flows, including mechanisms for improving collaboration in decision-making (Wesz; Formoso; Tzortzopoulos, 2018; Chiu; Cousins, 2020).

Collaboration plays a key role in the design process as it requires multidisciplinary knowledge, information exchange, and interactions between different disciplines involved (Mäki; Kerosuo, 2020). Collaboration in this context refers to decision-making through interactions among different professionals, creating shared knowledge, and integrating different perspectives to achieve the common goal of designing a new product (Kleinsmann, 2006).

Although the literature explores LPS in the design process of traditional construction projects (Chiu; Cousins, 2020; Mäki; Kerosuo, 2020), not much attention has been given to the specific context of MC, particularly concerning the integration between different planning levels, such as the alignment between design, manufacturing, and site assembly.

In this scenario, design planning and control faces specific challenges, mainly due to the need for integration between the commercial stage, which directly involves negotiations with client organizations, and technical stages, which include the development of detailed design for both manufacturing and site assembly. In fact, the distinguishing feature of this study is its coverage of the entire design management cycle, from the commercial phase to the detailed design, highlighting how this integration can overcome some specific challenges of different sectors involved in the delivery of MC projects.

Therefore, this study aims to devise a collaborative planning and control model to improve the design process in modular construction companies, considering the complexity attributes typical of this type of project and addressing the integration between design, manufacturing, and site-assembly processes. The model is grounded in the Last Planner System, being supported by collaborative practices to manage complexity and improve the reliability of design workflows.

Theoretical framework

Design process

In construction, design is often treated as a sequence of distinct tasks without adequately considering the interactions between these tasks and the relationships among the different parties involved (Tauriainen et al., 2016). This linear view of the design process leads to a lack of mutual commitments which makes it difficult a smooth design flow, resulting in a less predictable process (Shehab et al., 2023). Figure 1 presents a simplified model of the design process proposed by Pikas (2019), emphasizing the need to integrate technical and social dimensions. The main elements considered in this model are:

-

the people involved, such as customers or designers;

-

design tasks, which involve representations of problems and solutions;

-

the design process, which defines the flows of information and work;

-

the social process, consisting of interactions and communication among participants; and

-

the design context, which encompasses task, environmental, temporal and structural characteristics - all of which interact dynamically and require shared understanding to support the design flow (Pikas, 2019).

This model assumes that the design process is complex and fragmented and depends on designers and other parties involved working together, communicating, and developing a common, shared understanding that supports the flow of information and tasks (Pikas; Koskela, Gomes; 2024). Therefore, construction design should be a highly collaborative activity in order to achieve a suitable solution (Saad; Maher, 1996).

Modular construction has additional requirements regarding collaboration, compared to traditional construction projects, as there must be a strong emphasis on the integration between different project stages, such as conceptual design, detailed design, manufacturing, and site assembly (Wesz; Formoso; Tzortzopoulos, 2018). Due to the short project lead time, there are overlaps between different project stages, and component manufacturing often overlaps with site installation (Wesz; Formoso; Tzortzopoulos, 2018). For this reason, some design details need to be well-defined from the outset to support a timely flow of information among participants from different project stages (Hyun et al., 2020).

Figure 2 illustrates the nature of the interaction between different project stages in engineer-to-order modular construction, in contrast to make-to-order or make-to-stock stick-built construction. In MC, there are many interdependencies between different project stages, including design, manufacturing, logistics and site assembly, due to the short lead time and the large share of tasks undertaken in manufacturing plants (Hyun et al., 2020). Moreover, a manufacturing plant often needs to supply modules or components to different construction sites, which results in a high degree of structural complexity (Hyun et al., 2020). Therefore, as mentioned above, a significant challenge in the design process in this context is the need to fulfill a wide range of requirements for different projects, including customer needs, as well as manufacturing and site-assembly constraints.

Lean approaches and collaboration in design planning and control

The LPS has been developed as a construction planning and production control model, aiming to shield production from uncertainty and increase the reliability of workflows (Ballard, 2000). Although initially developed for site installation, it has also been successfully implemented in the design process (Shehab et al., 2023). Planning and control in LPS are divided into different hierarchical levels, allowing the early identification and removal of constraints (Ballard, 2000). Moreover, collaborative planning meetings, especially at medium- and short-term planning levels, contribute to improving communication, being an important mechanism for dealing with complexity in design (Wesz; Formoso; Tzortzopoulos, 2018). Therefore, LPS is effective for integrating the work of various design disciplines, and collaborative meetings are essential to fulfill client requirements and avoid conflicts and errors during this process (Tauriainen et al., 2016).

According to Wesz, Formoso, and Tzortzopoulos (2018), the implementation of LPS in the design phase of engineer-to-order industrialized building systems has shown significant benefits in terms of workflow reliability. However, some adaptations are necessary, such as two levels of medium-term planning to address internal and external constraints, integrated meetings for continuous adjustment of plans, and a decoupling point between conceptual and detail design. In addition, those authors have suggested a set of metrics to monitor batch sizes and planning failures, as well as the use of visual management devices to support collaborative planning. Therefore, collaborative planning and control are necessary not only for design but also to integrate the different stages in industrialized construction projects.

The concept of collaborative design encompasses different aspects, such as teamwork, communication, cooperation, and coordination (Pikas; Koskela; Gomes; 2024). The introduction of collaborative practices, such as participatory decision-making in LPS meetings, has shown positive results, such as increased team participation and a growing level of commitment among design team members, which contributes to the development of less centralized design planning and control systems (Wesz; Formoso; Tzortzopoulos, 2018).

Research method

Methodological approach

Design Science Research (DSR) was the methodological approach adopted in this investigation, involving the development of an empirical study carried out in close collaboration with a Modular Construction company. DSR is characterized by the development of a solution concept named artifact for solving classes of problems (March; Smith, 1995; Van Aken, 2004). In this investigation, the proposed artifact is a design planning and control model, i.e., an abstract representation of interrelated planning and control routines that can be adapted to different contexts. The purpose of this artifact is to be used by MC companies to devise design planning and control systems, aiming to improve workflow reliability. This study was approved by the university's Research Ethics Committee, which is registered in Plataforma Brasil with CAAE number 80464824.5.0000.5347.

Description of the company

The company involved in this investigation delivers projects for public and private clients from different states across Brazil, such as penitentiaries, schools, houses and healthcare units.

The design process usually involves developing customized solutions due to the need adapt existing solutions to client specifications, by combining different types of modules. The starting point for design is a set of pre-engineered modules, which allow the development of the design in a short lead time. This company was selected for having implemented Lean concepts for over three years, including a production planning and control system based on LPS.

Two projects from different types of clients were selected as units of analysis for this investigation. The first one was a penitentiary project delivered to a state government. In this case, there is a competitive bidding process based on standard technical specifications, in which the company with the lowest price gets the contract. This limits flexibility as adherence to predefined requirements is required. The second project was a school project for a private organization. In that case, there was more flexibility in design and the possibility of negotiations with client representatives, allowing the solutions available in the company to be effectively adapted to the project specific needs.

Research design

This investigation was divided into three phases, as shown in Figure 3, following the stages suggested by Holmström, Ketokivi and Hameri (2009):

-

Find and Understand the Problem;

-

develop and implement the artifact; and

-

assess the practical and theoretical contributions of the investigation.

The first phase, Find and Understand the Problem, consisted of understanding the practical problem faced by the company in planning and controlling the design of MC projects. This was based on document analysis, participant observation in design meetings, and interviews with design team members. Moreover, some data from production planning and control was used to analyze how design impacted downstream processes, including manufacturing and site assembly. In parallel, a literature review on design planning and control was carried out with the aim of identifying the knowledge gap. Based on the combination of literature review and empirical data, the complexity attributes of the design process in MC were identified. These findings informed the development of the planning and control model.

The second phase consisted of the development and implementation of the model, which is grounded in the LPS, and adapted to the context of MC. This phase involved several iterative cycles of development, implementation, assessment and reflection, with strong participation of design team members, similar to what was named action-design research by Sein et al. (2011). The first author was deeply involved in this process, actively monitoring the effects of the implemented changes in the design process.

Initially, the planning and control model was developed and applied in a single penitentiary project (Project A) involving both internal and outsourced designers. The initial version of the design planning and control system was devised with the strong involvement of the design manager and one of the leading internal designers. During this phase, short-, medium-, and long-term planning routines were defined, and linkages were established with site installation planning and control processes. Once a preliminary version of the model was outlined, it was presented to the design team in a training workshop. Following the implementation of Project A, some improvement opportunities were identified, leading to a refined version of the model. This refinement occurred after the completion of design activities in Project A and marked a shift in the design planning and control model, from a single-project approach to a multi-project perspective design, considering the need to manage simultaneous projects by the design team.

For Project B, the planning and control routines had to be adapted to reflect the concurrent management of multiple projects. An important addition to the model at this phase was introducing a tool for design status control for different projects being undertaken.

At the end of phase 2, the full version of the design planning and control model was devised, accommodating both single and multiple project contexts.

In the final phase, Analysis and Reflection, an assessment of the model was conducted, considering utility and applicability criteria, as suggested by March and Smith (1995). Different sources of evidence were used to assess the model:

-

semi-structured interviews with the design manager and internal designers;

-

analysis of design control metrics related to reliability and completeness of design batches; and

-

mapping information flows in the design process by using the Value Stream Mapping (VSM) tool, which is used to identify waste, constraints, and waiting time in existing processes, with the aim of suggesting process improvements (Shuker; Tapping, 2010); and

-

a workshop was held with stakeholders to discuss the VSM results collectively.

Reflections based on the analysis of the assessment data contributed to improve the understanding of the design planning and control model and its impact on performance. At the end of this investigation, a reflection on both the theoretical and practical implications of the investigation was carried out.

Data collection and analysis

Multiple sources of evidence were used in this investigation to triangulate data, as suggested by Yin (2003). Triangulation aims to increase the reliability of the information collected, enabling an in-depth understanding of the design process, and to support the formulation of a context-specific problem to be addressed (Yin, 2003).

Table 1 presents the sources of evidence used in the empirical study: direct observations in some work routines; participant observations in design meetings involving both internal and external designers, including 7 medium-term planning meetings, 6 short-term daily meetings, 5 meetings for model development and structuring of support tools, and 2 kick-off meetings for identifying project constraints. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with the design manager and four members of the company's design team. Moreover, specific interviews were conducted to develop the VSM. Finally, an analysis of documents was carried out, including project location-based systems, long-, medium-, and short-term plans, as well as reports on metrics. Furthermore, the model was assessed in a three-hour workshop by company’s representatives.

A thematic analysis, inspired by the approach proposed by Pope et al. (2000), guided the interpretation of data. The analysis focused on participants' perceptions of benefits, improvement opportunities, and challenges associated with the new planning routines, with special attention to collaboration practices. Those data were obtained in the interviews and triangulated with participant observations in planning meetings, and internal documents. The emphasis on collaborative practices was due to the fact that these play a key role in the implementation of the proposed model, as well as in the integration between design and production planning and control processes.

Moreover, a quantitative evaluation was performed by analyzing key performance metrics, such as the Percent Plan Complete (PPC) and the degree of completeness of design batches. Some additional metrics were also produced from the application of VSM.

Results and discussions

Overview of the existing design process

The design process for MC projects in the company was divided into two stages: the commercial stage and the detail design stage.

The commercial stage encompasses more than just design activities. It involves several professionals, including designers, cost estimators, and sales representatives, who collaborate to devise a design proposal and assess the feasibility of new projects. Initially, the commercial design stage receives a demand, and the team evaluates the feasibility of the project based on some initial information provided by the client organization. At this stage, the level of design development, deliverables, and deadlines are defined, considering the type of project and the necessary level of detail. Based on these definitions, a conceptual design proposal is presented to the client. After client approval, the conceptual architectural design is further developed and used as a reference for negotiation (or proposal, if it is a competitive bid) and contract finalization. The commercial stage concludes with an information handover meeting between the commercial design and the detail design teams when essential documents such as the conceptual design, contract, budget, construction schedule, and specifications are shared. Challenges at this stage include lack of standardization and poor consistency in the existing information, which often impacts deadlines and design quality. At this stage, the short lead time often results in superficial requirement analysis and unclear decision-making during negotiations with client organizations.

Once the project is approved, it transitions to the detailed design stage, in which the focus shifts mostly to design activities, including design for approval by local authorities, manufacturing and site-installation detail design, and as-built design. The process begins with the technical analysis of the information received and the preparation of a document with basic information and requirements, along with a materials list. The detail design stage is carried out by a team led by a design manager of seven designers in charge of developing manufacturing and site-assembly designs, electrical and plumbing designs, as well as structural designs. The design manager plays a central role in contracting design services, if necessary, and in the definition and implementation of the long-term plan, as well as assigning responsibilities to each designer for specific tasks. Information exchange is intense, especially with manufacturing and site-assembly managers.

The detail architectural design is initially developed by the preparation of preliminary design for different disciplines (e.g., plumbing, electricity, and structures). After this stage, the projects undergo clash detection and code-checking, taking into account technical and regulatory requirements. The detail design team also provides technical support to the manufacturing and construction site management teams during execution.

Key challenges were also identified in the detail design process, such as communication failures between the commercial and detail design teams, which result in inconsistencies in information exchange, such as poorly defined material specifications or late client-requested changes. These issues often lead to design rework and delays. Moreover, data from production planning indicated that design constraints were often identified as major causes of delays in material supply, manufacturing and site assembly.

Similar challenges have also been found in previous studies. Wesz, Formoso, and Tzortzopoulos (2018) pointed out the difficulties caused by very short lead times in design development, emphasizing the need to improve requirements capture and develop pre-engineered solutions for components. Similarly, Matt, Dallasega and Rauch (2014) pointed out that the complexity of construction projects often increases due to late design changes requested by clients. Therefore, in modular construction, design planning and control needs to be well structured, in which well-defined planning levels are established, the effort of capturing requirements must be increased, and there must be a good integration with planning and control routines adopted in manufacturing and site assembly.

Collaborative model for the design planning and control in modular construction

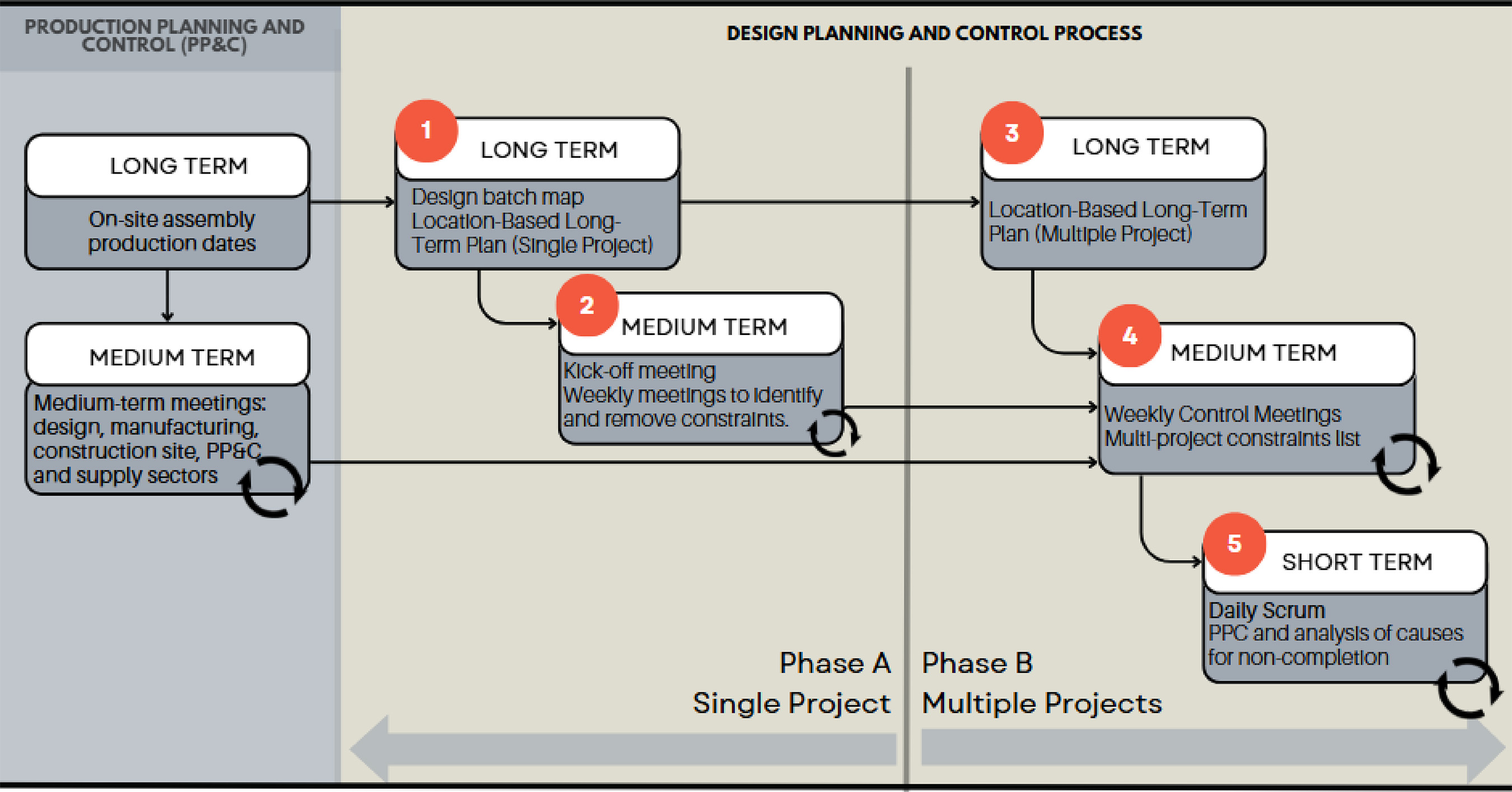

Based on the improvement opportunities identified in the first research stage, the design planning and control model for MC companies was devised (Figure 4). The model is structured into two main phases. Phase A is concerned with single projects and includes two planning levels (Processes 1 and 2) for both commercial and detailed design, while Phase B consists of integrated planning and control of multiple projects, divided into three planning levels (Processes 3, 4, and 5), being focused on detail design. Both phases complement and interact with each other. In fact, managing multiple projects occurs continuously throughout the project being based on a single long-term plan, in which new projects are added as contracts are signed.

In Figure 4, two Production Planning and Control (PP&C) levels are highlighted by using gray shading, as they represent a key source of information for design planning and control. In the company involved in the investigation, the PP&C system for site assembly combines the application of LPS and Location Based Planning and Control. The detail design and site assembly teams interact early in the project to develop the project's long-term plan. During the construction phase, this interaction continues through medium-term PP&C meetings. Information is sent weekly during these medium-term meetings to the design planning team. Additionally, informal communications may occur as needed.

Project planning begins with developing a long-term project plan, which is created before the design starts. This long-term plan defines the dates for on-site module assembly and factory production, being produced with inputs from representatives of key sectors within the company. At this point, it is necessary to define the project delivery date and production milestones, which are the point of departure for design long-term planning.

The next level of PP&C consists of weekly medium-term planning and control meetings in which constraints are identified and removed within a six-week horizon. Representatives from the design, manufacturing, construction site, planning and control, and supply sectors take part in these meetings. Constraints are documented in a shared spreadsheet accessible to all involved. The design manager is responsible for leading the removal of design-related constraints.

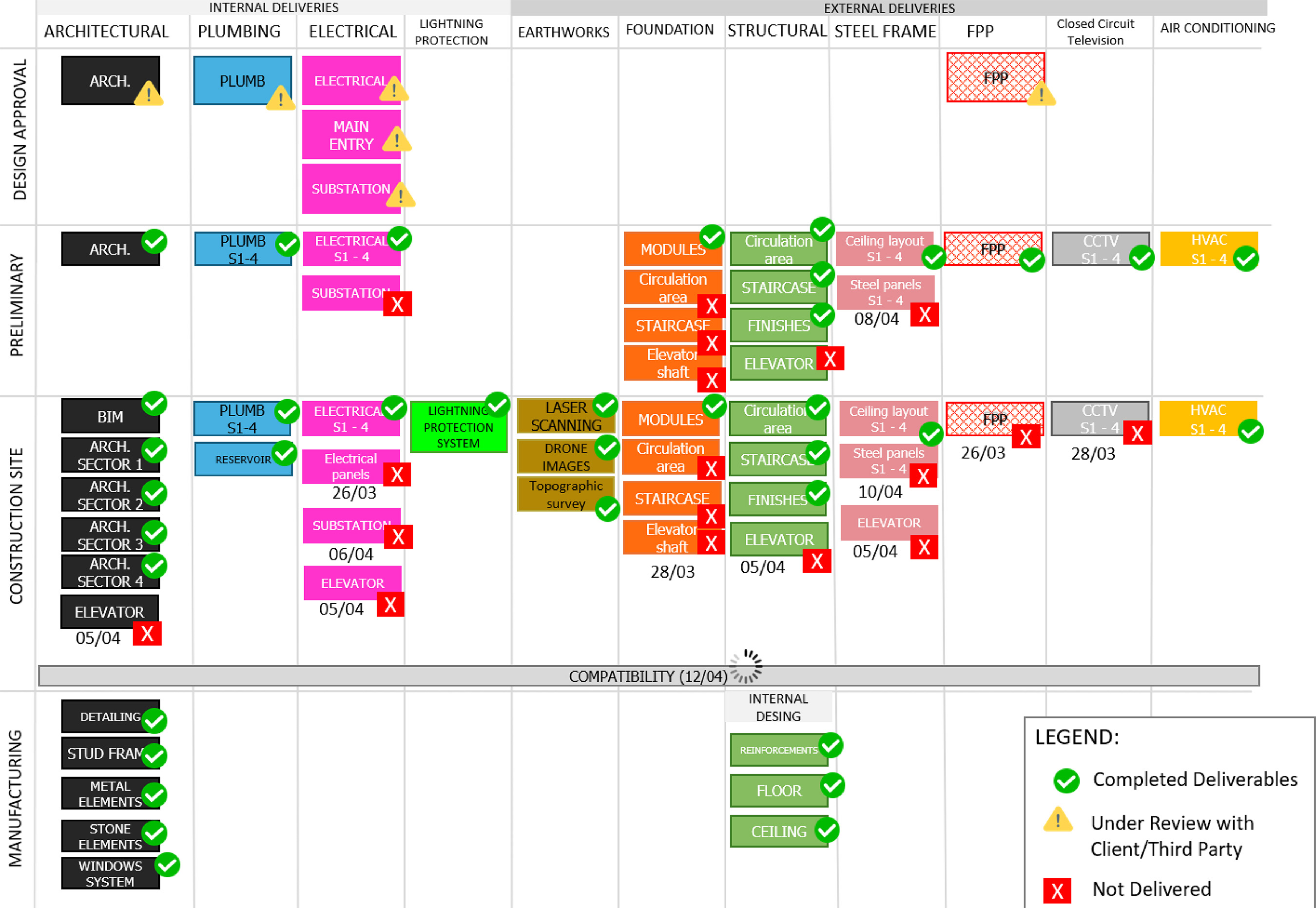

Process 1 marks the beginning of the design planning and control process. This stage involves creating a design batch map by dividing the project into small batches defined by disciplines. These batches are planned to be delivered according to milestones established in the long-term project plan. This map is used as a status control tool throughout the design process, marking completed or delayed design batches (Figure 5).

Based on this design batch map a long-term design plan, which is a kind of location-based plan. This plan outlines the durations of design packages, highlighting project delivery dates by discipline and their specific locations (Figure 6). Notably, this plan is divided into two parts: one for detail design for manufacturing and another for detail design for site installation.

Process 2 begins with the Kick-Off Meeting at the beginning of the design process for a specific project. This meeting aims to identify all potential constraints across the entire design, from start to finish. It involves the design manager, and internal and external designers, including designers involved in the commercial design stage, who have direct contact with the client. The aim of this meeting is to allow all those involved in the project to present their needs, clarify some uncertainties, establish commitments, and, most importantly, anticipate constraints that need to be removed to avoid design flow interruptions. Following this, a medium-term planning and control (Process 2) is established, involving weekly meetings to assess the following three weeks, focusing on identifying and removing constraints.

In Process 3, Phase B, the individual plans for each project (Process 1) are consolidated into a common long-term plan. This is done using a location-based planning software, in which design work packages are entered to control deadlines and visualize demand. Additionally, this plan provides an overview of design activities taking place in all ongoing projects, enabling the design manager to assess whether the capacity of the internal design team is sufficient, and if external designers need to be hired. This integrated plan, referred to as the multiple long-term plan, consolidates all location-based schedules of current design projects. In the example shown in Figure 7, five projects are being executed simultaneously, and the distribution of design work packages across them can be visualized.

Process 4 consists of regular meetings involving the design manager and internal designers to identify and remove constraints. This results in a plan with a 15-day horizon and weekly control cycles. A multi-project constraint spreadsheet is used to define deadlines and those responsible for removing constraints. This spreadsheet also includes constraints identified in the medium-term meetings of the previous processes (medium-term of PP&C and Process 2).

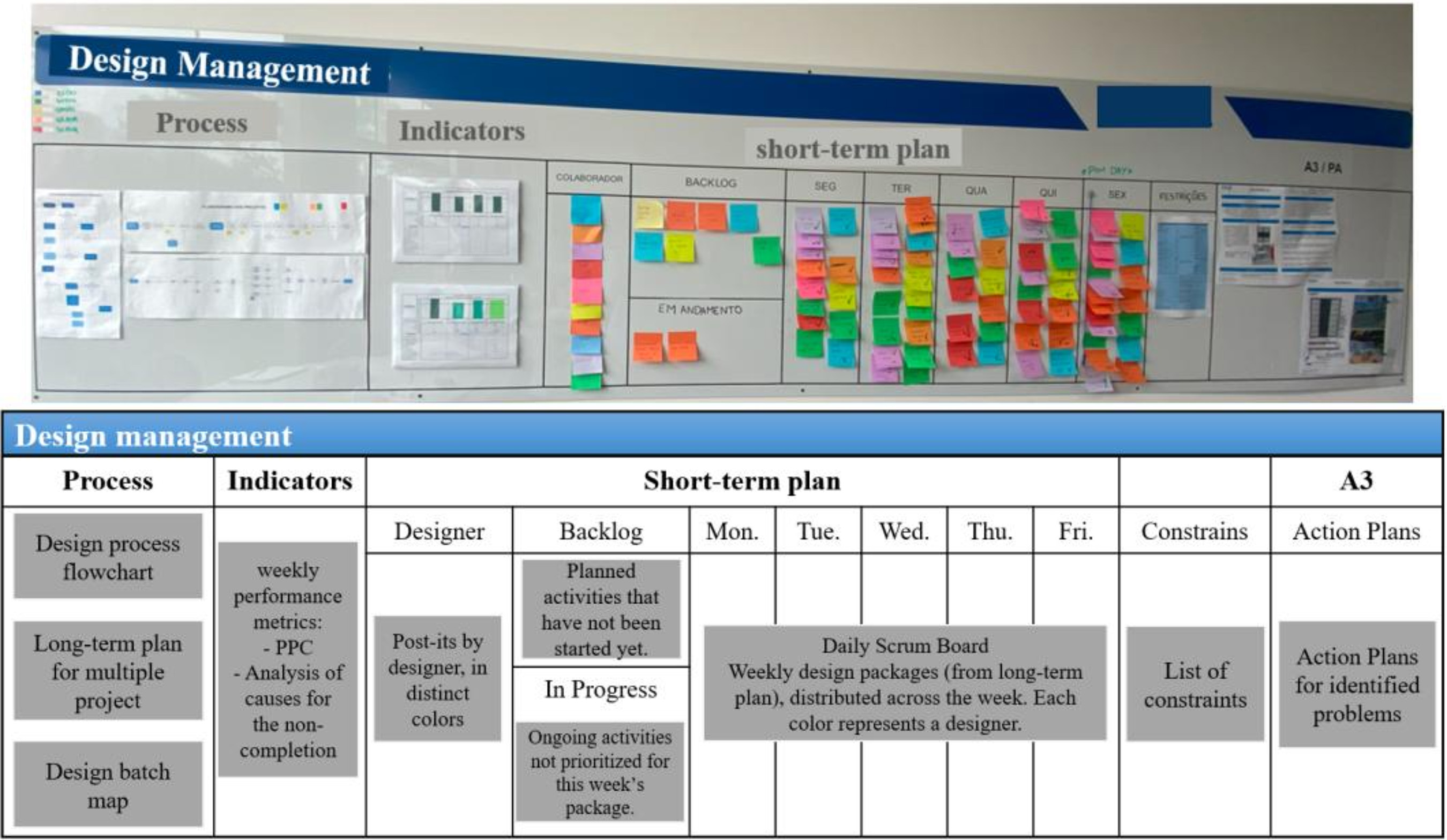

In Process 5 (short-term level of Phase B), weekly plans are created using an adapted version of daily Scrum and aligned with the LPS. While Scrum is based on Agile Project Management and emphasizes iterative development and adaptability, LPS originates from Lean Construction, focusing on workflow reliability and transparency. Although these are distinct approaches, they share similarities that complement each other (Hamerski; Formoso; Isatto; 2024). Scrum was used to visually manage short-term plans and drive process improvement, while LPS was adopted for weekly short-term control meetings, from which performance metrics are produced, such as the Percent Plan Complete (PPC) and analysis of causes for the non-completion of work packages.

The Scrum process starts by reviewing the long-term plan to identify deliverables assigned to designers, by using sticky notes on the board. In the first daily meeting on Monday morning, designers assess their tasks and adjust them based on feasibility. Completed tasks are marked with a check on the post-it, while those that are not finished are rescheduled. In subsequent daily meetings, the design manager confirms the completion of previous tasks and makes adjustments for the day ahead. At the end of the week, the manager compares the planned tasks with the completed ones and calculates the metrics according to LPS.

To support coordination between the tasks of various detail design team members, daily control meetings were held to review progress, adjust tasks, and track performance, which is displayed on the design management board (Figure 8). This board also includes the long-term plans (Process 3) and the list of constraints (Process 4).

By integrating long-, medium-, and short-term planning levels and fostering collaboration across different organizational units, the model is aligned with recommendations from the literature. Williams (1999) suggested that collaborative and decentralized planning is more adequate for highly complex projects. Bataglin et al. (2020) proposed the adoption of confirmation points at the look-ahead planning level based on information collected in downstream processes in order to deal with uncertainty in demand. Wesz, Formoso, and Tzortzopoulos (2018) further emphasize that planning and control must be hierarchical, making it possible to integrate planning and control among different processes and managerial levels.

Collaboration at different planning levels

Table 2 provides some details about collaborative practices that are part of the proposed model.

These practices correspond mainly to collaborative meetings and visual management (VM) tools at different planning levels. In collaborative meetings, participants can communicate, establish commitments and exchange information. t VM tools form information fields that support and foster collaboration through visualization mechanisms.

Collaborative meetings occur at different planning levels and involve both designers and other stakeholders within the company. In Phase A, during the PP&C long-term and medium-term levels, meetings include managers from other company sectors (planning, manufacturing, site assembly and material supply) as well as the design manager. These multidisciplinary meetings are part of the early model stages, still within the PP&C phases, representing moments of integration and information exchange among the various disciplines. The collaborative meetings involving different stakeholders promote the leveraging of diverse perspectives, which contributes to the identification of constraints, promotes realistic goal-setting, and enhances commitment, all of which contribute to improving project resilience (Hamerski et al., 2023).

In addition to the multidisciplinary meetings described above, there are collaborative meetings involving only the design team. These practices occur primarily during the medium- and short-term planning stages and focus on coordination among designers. In these regular planning and control meetings, such as the short-term (daily, in Phase B) and medium-term meetings (in both Phases A and B), designers were able to visualize the activities of all team members and assess the effectiveness of previous planning cycles. Regarding planning for future periods, the design participants made joint commitments, meaning that they shared risks and responsibilities and were committed to a common goal. Design meetings also represented opportunities for sharing and exchanging information between designers, especially when one of them was facing difficulties.

Table 3 lists the VM practices implemented and how each of them was connected to different stages of the proposed model. There was evidence of the positive impact of visual management in the design planning and control process:

-

information exchange between different company's sectors was improved, as perceived by designers; and

-

managers became more committed to meeting deadlines.

Moreover, as suggested by Brady et al. (2018), VM supported the definition of shared goals and foster proactive problem-solving.

The long-term plan of phase B, previously illustrated in Figure 7, was an important innovation introduced by the model, as it provided an overview of planning goals for all projects and supported the distribution of work among design team members. For example, there were situations in which some designers were able to anticipate their own work overload. As a result, collective decisions were made regarding the need to outsource some design activities or redistribute them among other design team members.

Additionally, the Design Management Board supported internal collaboration, i.e., among design team members, as these could identify interdependencies between design batch packages and seek collaboration from other disciplines. This tool also supported collaboration among representatives of different company sectors. It is displayed in an open location, easily accessible to everybody in the company, e.g., the factory manager. The schematic representation of the tool is presented in Figure 8 above. In fact, the positive impact of the visual collaborative boards has confirmed the results of the study carried out by Pikas et al. (2022).

Discussion

Model assessment

As mentioned in the research method section, three main sources of evidence were used for assessing the utility and applicability of the model: semi-structured interviews with design team members, participant observation in planning meetings, and planning and control metrics.

The interviews indicated that visual tools and structured planning routines had played a key role in improving the design team coordination and engagement. According to one architectural designer, the implemented tools were "essential for us to organize things, both visually for those coordinating and for those collaborating", and that the team now "have the most important things visible". This designer also mentioned that it is important to have a digital copy of the VM board available, so it is easy to update it and it accessible from other locations.

The interviews also revealed that the adoption of Scrum-based planning allowed designers to manage their tasks better, anticipate workloads, and adjust activities as needed. With a clear view of their weekly work packages, designers reported having a better understanding of their tasks and priorities, which improved overall workflow predictability. According to the electrical system designer, he can “take a look to get a sense of what I need to deliver and what might be good to get ahead on”. The design manager highlighted the role of daily meetings in aligning the work of the design team with common goals. By visualizing their workload and following a structured planning routine, design members were able to produce reliable design plans, even considering the need to work on a number of projects simultaneously.

Regarding planning and control metrics, a data analysis was carried out for a single school project (see long-term in Figure 6). Firstly, the PPC metric was monitored, ranging from 83% to 94%, which is considerably high for the application of the LPS in design (Wesz; Formoso; Tzortzopoulos, 2018). These results provide evidence that the planning and control process was highly reliable.

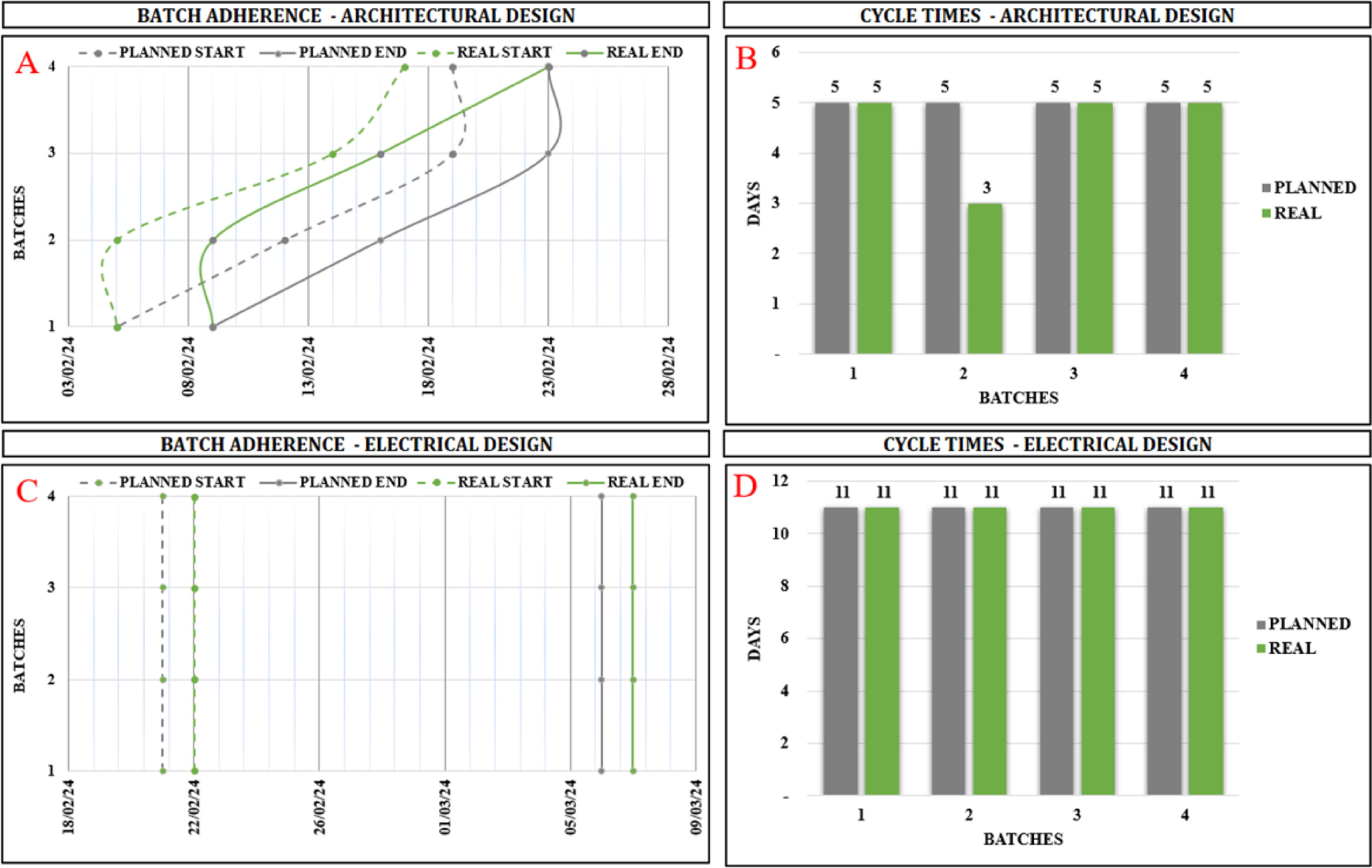

Two other metrics were used to assess the effectiveness of the planning and control model: batch adherence and cycle time variation, both metrics suggested by Barth and Formoso (2020)

This analysis considered four main internal design batches: the first two were part of manufacturing detail design (window systems and module detailing), and the other two were part of site-assembly detail design (architectural design and electrical design).

The window system design (Figure 9a) had slight delays in both start and end dates, but the impact of those delays in the overall project was minimal. However, the real cycle time was longer than planned in three batches (Figure 9). This can be attributed to unexpected events, adjustments, or client-requested changes in design.

By contrast, the module detailing batch (Figure 9c and Figure 9d) had a shorter cycle time than planned, indicating an efficient execution. One batch had a delay, but overall batch adherence was maintained, suggesting effective coordination.

Architectural design (Figures 10a and 10b) followed the planned schedule, with some design batches delivered ahead of schedule. In the electrical design (Figures 10c and 10d), full adherence to the planned cycle times was achieved, but the design was delivered as a single package rather than in batches. This was due to the interdependencies within electrical systems, making phased deliveries less feasible.

Improvement opportunities

Value Stream Mapping (VSM) was used to identify improvement opportunities in the design process after implementing the model. This assessment relied on internal planning documents, especially those related to short-term scheduling, to analyze lead time (LT) and cycle time (CT).

The VSM covered the entire design process, from conceptualization to final delivery (Figure 11) and was divided into two activities bands: the design activities essential for defining production pace (blue band), and the construction stages directly connected to manufacturing (yellow band). Activities were categorized into internal processes (blue boxes) and outsourced processes (gray boxes). The LT and the CT were compared to identify constraints and inefficiencies in the design flow.

The Start date (SD) and End date (ED) for each phase were extracted from long-term planning spreadsheets. In the case of parallel activities, CT and queue time (QT) were analyzed. The activity exhibiting the longest CT was selected for analysis, considering MEP design, Basic design, and factory detail design. The durations associated with factory detail design were chosen due to its higher CT and QT compared to the other two activity packages. A similar selection process was applied to the parallel activities of MEP revision, list of materials, and interdisciplinary coordination – for the activities within the yellow band. Many MEP design activities were executed by external teams, making it very difficult to monitor CT. The parallel activity with the greatest QT was chosen to be included in the flow line. However, the uncertainty introduced by outsourced teams and the need for strategies to mitigate delays and improve predictability in their deliverables was highlighted.

The current state VSM revealed a lead time of 148 days for design activities, while the CT was only 29 days, mostly due to long waiting periods between activities. Key factors for this discrepancy include multiple internal revisions, waiting for design definitions, and rework due to the lack of integration between commercial and detail design. In the analyzed school project, the difference between the planned deadline and the QT required for completion was 129 business days, with the main causes being frequent revisions, delays from outsourced teams, and initial approvals without proper validation of requirements.

The main improvement opportunities identified in the VSM include the need for an effective process for capturing and analyzing client requirements, especially in the commercial stage, enhanced collaboration between different sectors and design teams, the implementation of intermediate collaborative design reviews, and improve the definition of modular components at different hierarchical levels.

Practical and theoretical implications of the study

Based on the assessment of the model presented above, the following contributions of the model must be highlighted:

-

the strong collaboration and openness in sharing information and adjusting short-term plans during the daily collaborative planning meetings, which was supported by Scrum, had substantially improved commitment management. The role of LPS in the management of commitments has already been discussed in the literature by Viana, Formoso and Isatto (2017), but most previous studies on that topic have been focused on the production stage of traditional construction. One important contribution of this investigation is about how to manage commitments in design planning and control, in the context of modular construction, in which it is necessary to integrate the planning and control processes of different construction stages;

-

visual management is also an important element of the model, especially when using the VM board. That visual device provided key information about the status of all ongoing projects in a single interface, also contributing to commitment management. In fact, this tool not only supported planning meetings but was located in an open space in the company's headquarters, where anybody could have access, including representatives of other company sectors. This type of information field was suggested by Brady et al. (2018), but this investigation extended its application to the context of modular construction design. An additional VM practice adopted in the empirical study is an on-line system updated in real time with data displayed in the VM board, making information available also for external stakeholders;

-

besides the use of traditional Last Planner metrics, some metrics used in this investigation are not commonly adopted for design planning and control, such as batch adherence and cycle time. These metrics are directly connected to applying the Lean principles of reducing the batch size (Koskela, 2000) in the design process. However, as pointed out by Wesz, Formoso and Tzortzopoulos (2018) it is difficult to apply the batch adherence metric across all disciplines fully: in this investigation, the unit of control in manufacturing and site assembly was a module, whereas in design it depends on the discipline and specific deliverables;

-

both qualitative and quantitative evidence suggest that the implemented model has contributed to improving workflow predictability and efficiency. It also enabled managers to make more informed decisions, and to connect those decisions with some strategies adopted by the company for dealing with different clients. However, the observed client-induced design changes highlight the need for flexibility and active monitoring of design variability, as pointed out by Wesz, Formoso and Tzortzopoulos (2018);

-

the model also facilitated the engagement of both internal and external designers in the planning and control process. In fact, joint meetings with outsourced teams played a key role in reinforcing commitment to deadlines. Another significant improvement was the development of a long-term design planning tool, which allowed team members to anticipate capacity constraints and justify outsourcing design work when necessary. Conforto et al. (2014) pointed out the benefits of these practices, such as enhancing team communication, and fostering adaptability in complex environments; and

-

the application of VSM as an assessment tool also provided some insights on how to improve the design process. The main opportunities identified were to revise the distribution of design tasks between the conceptual and the detail design stages in order to avoid rework and also to reduce design lead-time for single projects by eliminating design errors and rework, reducing waiting time due to delays in product definitions, and expediting design checks by using digital systems (e.g., automated checking of codes and production constraints).

Conclusions

This study has devised a collaborative design planning and control model for modular construction companies, which is strongly based on a hierarchical decision-making process which involve three planning levels: long, medium, and short-term. Besides the adaptation of the Last Planner System to the design stage of MC projects, of the model was also based on core Lean Production principles, such as reduction of batch size, increase of process transparency, and flexibility of output. The model also includes a set of collaborative practices used as part of planning and control meetings, which help manage the type of complexity that exists in modular construction companies. They enable interactions that lead to integrated decision-making among different stakeholders in the design process. For example, the meeting routines defined in the model facilitate information exchange and coordination of design tasks, covering both component manufacturing aspects and module installation on construction sites. Besides, visual tools (such as a design batch map and a location-based plan) not only enhance communication but also contribute to improving collaboration among design team members.

A key contribution of this model compared to traditional design planning and control practices is the emphasis on collaboration at multiple planning and control levels. The structured interactions fostered by the model have enhanced information exchange, transparency, and shared commitment, which represent a major change in relation to the typical informal interactions between design team members. The implementation of collaborative planning and control meetings, supported by visual tools, has improved the integration between design team members, and also with representative from other stages of modular construction projects, reducing inconsistencies and delays.

From a theoretical perspective, this investigation has provided insights into the nature of the design process in modular construction companies, which introduces additional demands in planning and control systems, including short lead time, intensive collaboration between internal and external stakeholders, use of standardized pre-engineered design solutions, and the need to be effective in understanding client requirements in order to create mechanisms to offer flexibility of output for specific projects.

Regarding the limitations of this investigation, it must be pointed out that the development of the model was based on a single empirical study. Further work is necessary to test the utility and applicability of the model, considering a wide range of business models and product structures in modular construction. Another limitation of this study was the fact that the design control metrics could not be fully explored to identify improvement opportunities in the company investigated, due to the limited time for the development of the empirical study.

Moreover, future research could explore the process of implementing collaborative design planning and control practices, including the definition of the sequence of implementation, systematic use of performance metrics, and mechanisms for monitoring the commitment and engagement of design teams in the planning and control process.

Declaração de Disponibilidade de Dados

Os dados de pesquisa estão disponíveis no corpo do artigo.

Referências

- BALLARD, H. G. The Last Planner System of production control Birmingham, 2000. 193 f. Doctoral Dissertation, The University of Birmingham, Birmingham, 2000.

- BALLARD, H. G.; HOWELL, G. Shielding production: essential step in production control. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, v. 124, n. 1, p. 11-17, Jan./Feb. 1998.

- BALLARD, H. G.; TOMMELEIN, I. Current process benchmark for the Last Planner® System of project planning and control. Berkeley: Project Production Systems Laboratory, UC Berkeley, 2021.

- BARTH, K. B.; FORMOSO, C. T. Requirements in performance measurement systems of construction projects from the lean production perspective. Frontiers of Engineering Management, v. 8, p. 442-455, May 2020.

- BATAGLIN, F. S.; VIANA, D. D.; FORMOSO, C. T. Design principles and prescriptions for planning and controlling engineer-to-order industrialized building systems. Sustainability, v. 14, n. 24, 2022.

- BATAGLIN, F. S. et al. Model for planning and controlling the delivery and assembly of engineer-to-order prefabricated building systems: exploring synergies between lean and bim. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, v. 47, n. 2, p. 165-177, fev. 2020.

- BRADY, D. A. et al. Improving transparency in construction management: a visual planning and control model. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, v. 25, n. 10, p. 1277-1297, nov. 2018.

- CHIU, S.; COUSINS, B. Last Planner System® in design. Lean Construction Journal, Oakland, p. 78-99, 2020.

- CONFORTO, E. C. et al. Can agile project management be adopted by industries other than software development? Project Management Journal, v. 45, n. 3, p. 21-34, 2014.

- ELFVING, J. A. A decade of lessons learned: deployment of lean at a large general contractor. Construction Management and Economics, v. 40, n. 7/8, p. 548-561, ago. 2022.

- FUNDLI, I. S.; DREVLAND, F. Collaborative design management: a case study. In: ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR LEAN CONSTRUCTION, 22., 2014, Oslo Proceedings [...] Oslo, 2014.

- HAMERSKI, D. C.; FORMOSO, C. T.; ISATTO, E. L. Integrating lean production and agile project management: a planning and control model for multi-project environments in construction. International Journal of Construction Management, p. 1-10, out. 2024.

- HAMERSKI, D. C. et al. The Last Planner System as an emergent production planning and control method: the role of multiple representations. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, v. 150, n. 11, p. 1-14, nov. 2024.

- HAMERSKI, D. C. et al. The contributions of the Last Planner System to resilient performance in construction projects. Construction Management & Economics, v. 41, p. 1-18, 2023.

- HOLMSTRÖM, J.; KETOKIVI, M.; HAMERI, A.P. Bridging practice and theory: a design science approach. Decision Sciences, v. 40, n. 1, p. 65-87, fev. 2009.

- HYUN, H. et al. integrated design process for modular construction projects to reduce rework. Sustainability, v. 12, n. 2, p. 530, jan. 2020.

- INNELLA, F.; ARASHPOUR, M.; BAI, Y. Lean methodologies and techniques for modular construction: chronological and critical review. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, v. 145, n. 12, p. 1-18, dez. 2019.

- KLEINSMANN, M. S. Understanding collaborative design Delft, 2006. 309 f. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, 2006.

- KOSKELA, L. An exploration towards a production theory and its application to construction 2000. Thesis (PhD) – VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, 2000.

- MÄKI, T.; KEROSUO, H. Design-related questions in the construction phase: the effect of using the last planner system in design management. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, v. 47, n. 2, p. 132-139, fev. 2020.

- MARCH, S. T.; SMITH, G. F. Design and natural science research on information technology. Decision Support Systems, v. 15, n. 4, p.251-266, 1995.

- MATT, D. T.; DALLASEGA, P.; RAUCH, E. Synchronization of the manufacturing process and on-site installation in ETO companies. Procedia, v. 17, p. 457-462, 2014.

- MOLAVI, J.; BARRAL, D. L. A construction procurement method to achieve sustainability in modular construction. Procedia Engineering, v. 145, p. 1362-1369, 2016.

- MOUNLA, K. E. et al. Lean-bim approach for improving the performance of a construction project in the design phase. Buildings, v. 13, n. 3, p. 654, 28 fev. 2023.

- OLAWUMI, T. O. et al. Automating the modular construction process: a review of digital technologies and future directions with blockchain technology. Journal of Building Engineering, v. 46, p. 103720, abr. 2022.

- OLIVIERI, H. et al Survey comparing critical path method, last planner system, and location-based techniques. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, v. 145, n. 12, dez. 2019.

- PIKAS, E. Causality and interpretation: integrating the technical and social aspects of design. 2019. Doctoral Dissertation, Aalto University, 2019.

- PIKAS, E.; KOSKELA, L.; GOMES, D. Building design collaboration: what, why, and how. In: MORADI, S. et al. (ed.). Routledge handbook of collaboration in construction London: Routledge, 2024.

- PIKAS, E. et al. Digital Last Planner system whiteboard for enabling remote collaborative design process planning and control. Sustainability, v. 14, n. 19, p. 12030, set. 2022.

- POPE, C. Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data. BMJ, v. 320, n. 7227, p. 114-116, jan. 2000.

- SAAD, M.; MAHER, M. L. Shared understanding in computer: supported collaborative design. Computer-Aided design, v. 28, n. 3, p.183–192, mar. 1996.

- SEIN, M. et al. Action design research. Mis Quarterly, v. 35, n. 1, p. 37, 2011.

- SHEHAB, L. et al. Last planner system framework to assess planning reliability in architectural design. Buildings, v. 13, n. 11, p. 2684, 25 out. 2023.

- SHUKER, T.; TAPPING, D. Value stream management for the lean office New York: Productivity Press, 2010.

- TAURIAINEN, M. et al. The effects of bim and lean construction on design management practices. Procedia Engineering, v. 164, p. 567-574, 2016.

- VAN AKEN, J. E. Management research on the basis of the design paradigm: the quest for field-tested and grounded technological rules. Journal of Management Studies, v. 41, n. 2, p. 219-246, 2004.

- VIANA, D. D.; FORMOSO, C. T.; ISATTO, E. L. Understanding the theory behind the Last Planner System using the Language-Action Perspective: two case studies. Production Planning & Control, v. 28, n. 3, p. 177-189, 2017.

- WESZ, J. G. B.; FORMOSO, C. T.; TZORTZOPOULOS, P. Planning and controlling design in engineered-to-order prefabricated building systems. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, v. 25, n. 2, p. 134-152, mar. 2018.

- WILLIAMS, T. M. The need for new paradigms for complex projects. International Journal of Project Management, v. 17, n. 5, p. 269-273, 1999.

- YIN, R. K. Case study research: design and methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2003.

Edited by

-

Editor:

Enedir Ghisi

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

18 Aug 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

31 Jan 2025 -

Accepted

18 May 2025

A design planning and control model for modular construction companies

A design planning and control model for modular construction companies

Source: adapted from

Source: adapted from  Source: adapted from

Source: adapted from