ABSTRACT

Traditional methods for assessing crop water status have limited practicality for field applications. Conversely, remote sensing via remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) offers a promising alternative, though its effectiveness requires validation in specific studies. This study utilized RPA-derived imagery to support strategies for monitoring water deficit (WD) in corn crops and enabling yield prediction. The AG 1051 corn genotype underwent deficit irrigation levels (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100% of crop evapotranspiration—ETc) at different phenological stages: initial (E1), vegetative growth (E2), flowering (E3), and physiological maturity (E4) in Iguatu, Ceará, Brazil. We measured ten vegetation indices (VIs) and ear and biomass yield. Pearson's correlation analysis revealed that, during E2, the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) (r = 0.98) and green leaf index (GLI) (r = 0.99) were the most reliable for distinguishing water stress levels. These indices were also effective in predicting yield in E2 through regression analysis. The findings demonstrate that vegetation indices derived from RPA imagery provide a robust method for assessing water conditions and forecasting yield.

KEYWORDS

water availability; drones; remote sensing; Zea mays L.

INTRODUCTION

Remote sensing (RS) techniques involve acquiring information from the Earth's surface by detecting visual or energetic signals emitted or reflected, without direct physical interaction between sensors and target objects. In the 21st century, the widespread adoption of remotely piloted aircraft (RPAs) has enabled the integration of sensors into these platforms, enhancing target monitoring capabilities and improving the spatial and temporal resolution of assessments (Cardoso et al., 2021; Paolinelli et al., 2022).

RPAs and RS have thus become essential technologies in precision agriculture, facilitating advanced observational approaches. Oliveira et al. (2020) emphasize the significance of aerial imagery and vegetation indices (VIs) derived from RPA-mounted sensors for crop monitoring and decision-making. These technologies enable real-time, non-destructive plant diagnostics, supporting strategies to mitigate the adverse effects of abiotic and biotic stresses, ultimately enhancing precision agriculture practices.

One critical application of this technology is optimizing water productivity in crops. VIs can effectively detect plant water stress by identifying physiological changes, such as reduced chlorophyll concentration in plant tissues. This reduction allows pigments like carotenoids to become more prominent, altering spectral responses (Jensen, 2007).

Corn (Zea mays L.) is one of the most widely cultivated cereals worldwide, grown under rainfed and irrigated conditions. It plays a vital role in society, valued not only for the nutritional quality of its grains but also for its diverse applications. However, grain and biomass productivity can be significantly affected by water deficit, with its impact varying based on the growth stage, intensity, and duration of the stress (Sah et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2021).

Given this challenge and the practical potential of RS techniques, researchers have increasingly explored their applications in corn cultivation. Recent studies, such as Zhang et al. (2021) and Lopes et al. (2024), indicate that VIs correlate significantly with physiological parameters related to plant water status. Similarly, studies by Andrade Junior et al. (2021) and Cheng et al. (2022) confirm that VIs derived from multispectral imagery provide a reliable approach for monitoring water stress in corn, potentially serving as an alternative to thermal sensors.

With the ability to assess plant health using VIs, research by Feizolahpour et al. (2023), Shao et al. (2023), and Leitão et al. (2023) suggests that RPA-derived imagery offers a promising strategy for predicting grain and biomass yield, supporting decision-making in corn production. However, critical gaps remain, particularly regarding the validation and refinement of these techniques to account for the edaphoclimatic conditions of different production environments and the specific spectral responses of regionally dominant commercial corn genotypes. Establishing a robust methodology for diagnosing water stress and predicting yield requires a precise VI interpretation and practical adoption.

Furthermore, existing vegetation classifications, such as those by Berhan et al. (2011), provide general guidelines but may not accurately reflect the structural, thickness-related, and canopy-specific characteristics of target crops. Additionally, the most suitable VI for monitoring one crop may not be effective for others (Ihuoma & Madramootoo, 2019). The timing of aerial surveys is also crucial, as not all phenological stages respond equally to VIs. Thus, selecting the appropriate growth stage for image acquisition is a key factor in detecting water deficit using RPA imagery.

Given these considerations, this study aims to leverage RPA-derived imagery to develop a methodological strategy for monitoring water deficit across different corn phenological stages and predicting crop productivity. Specifically, we seek to identify the VIs and phenological stages most responsive to water stress, evaluate the correlation of VIs with biomass and ear yield, and thus propose a classification system for VIs based on their sensitivity to water deficit in corn crops.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Location and characterization of the study site

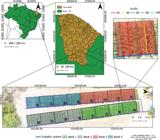

The study was conducted in an experimental field of the Federal Institute of Education, Science, and Technology of Ceará (IFCE) in Iguatu, Ceará, Brazil (6°23’31’’S, 39°15’59’’W, 220 m above sea level) between October and December 2023 (Figure 1). The region has a hot semiarid climate (BSh) according to the Köppen classification.

During the experimental period, as illustrated in Figure 2, total recorded rainfall was 9.41 mm, which was deducted from the volume of water applied in the treatments. The mean reference evapotranspiration (ETo) was 5.28 mm day⁻1, and the average temperature was 29.98 °C.

Daily evapotranspiration (mm), rainfall (mm), and average temperature (°C) during the experimental period. DAE: days after emergence; E1: initial growth; E2: vegetative growth; E3: flowering; E4: physiological maturity. * = the day the flight took place.

The soil is classified as Eutrophic Red-Yellow Argisol with a sandy texture, a pH of 6.73, electrical conductivity of 0.37 dS m⁻1, and a bulk density of 1.23 Mg m⁻3. The experimental units consisted of 4.0-m-long corn rows, with five plants per meter (0.20 m spacing between plants) and 1.0-m spacing between rows. A randomized block design (RBD) was used with four replications in a split-plot scheme: four phenological stages × five water replacement levels, as depicted in Figure 1.

The treatments were applied to Zea mays L. (hybrid AG 1051), a semi-early cycle variety suitable for whole-plant silage and green corn production. Five water replacement (WR) strategies were tested, varying the onset and duration of deficit irrigation at specific phenological stages: E1 (initial growth), E2 (vegetative growth), E3 (flowering), and E4 (physiological maturity) (Table 1). These phenological stages were defined according to Santos et al. (2014).

Irrigation was performed daily between 9:00 AM and 12:00 PM using a localized drip system with emitters delivering a flow rate of 4.44 × 10⁻⁷ m3 s⁻1 at a pressure of 98.064 kN m⁻2. The WR was calculated based on climatic data, with treatments replacing 100%, 80%, 60%, 40%, or 20% of daily evapotranspiration losses (ETc). ETo was estimated using the Penman-Monteith method (Allen et al., 1998), incorporating data from a nearby agrometeorological station and crop coefficients (Kc) from Santos et al. (2014). In all treatments, except for the targeted phenological stage under deficit irrigation, plants received full daily replenishment (100% ETc) throughout the remaining growth stages. Table 2 presents the irrigation depths applied since sowing and the total water depth at each stage.

Irrigation water depths applied during corn crop growth stages (E1, E2, E3, and E4) and the entire experimental period (in mm) for water replacement (WR) treatments, including full irrigation (100% of ETc) and deficit levels (20%, 40%, 60%, and 80% of ETc).

Imaging and indices used

Aerial surveys were conducted weekly between 11:00 AM and 12:00 PM and at the end of each phenological stage, with the first flight occurring at the end of E1, totaling ten analysis periods. The image acquisition schedule was distributed as follows: one flight in E1, five in E2, two in E3, and two in E4.

A DJI Phantom 4 RPA equipped with a Mapir Survey 3W sensor was used to capture images in the red (660 nm), green (550 nm), and near-infrared (NIR, 850 nm) bands (RGN). Additionally, the RPA's native sensor was used to acquire images in the visible spectrum (RGB: red – 660 nm, green – 550 nm, blue – 475 nm).

The RGN sensor data were converted from digital numbers to reflectance values using a calibration target. Flights were conducted at an altitude of 19.81 m and a speed of 3.22 km h⁻1, with lateral and frontal overlaps set at 80%. Aerial surveys were planned using the DroneDeploy platform, resulting in a Ground Sample Distance (GSD) of 9.08 mm pixel⁻1 for the RGN sensor and 8.50 mm pixel⁻1 for the RGB sensor.

Ten vegetation indices (VIs) were used, including five multispectral indices (MSVIs) and five visible spectrum indices (VSVIs), as shown in Table 3. The VIs were calculated using the "Raster Calculator" tool in QGIS 3.28. The mean VI values for the corn canopy in each experimental unit were extracted using the "Zonal Statistics" plugin in QGIS. Spectral values were obtained based on a shapefile delineating the vegetated area within each experimental unit. The useful area was defined as the maximum vegetation cover, excluding regions where overlap between adjacent experimental units could occur, particularly between E3 and E4, where plant density led to canopy overlap.

Characteristics of the vegetation indices used. R – red band, G – green band, B – blue band, and NIR – near infra-red band.

Yield data

The response variables measured were total green ear yield without husk (TY, Mg ha⁻1) and final dry biomass (FDB, Mg ha⁻1) accumulated above the soil surface. Data were collected at 70 DAE during the pasty grain stage (R4) from five plants per experimental unit.

TY was determined by averaging the green ear masses at harvest. FDB was obtained by collecting the aerial parts of the plants near the soil surface, followed by drying in an oven at 60 °C until a constant mass was reached.

Statistical analysis

Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, confirming that the dataset followed a normal distribution. Pearson correlation analysis was then performed between the mean vegetation index values across each stage and the water replacement levels (WR, % ETc) to identify the most responsive multispectral (MSVI) and visible spectrum (VSVI) indices, as well as the phenological stage most sensitive to water deficit (WD).

To elucidate the relationships between VIs and WR levels and to estimate TY and FDB based on mean index values throughout each stage, we tested linear, quadratic, cubic, and fourth-degree regression models using analysis of variance (ANOVA) at a 5% probability level. Behavior graphs were constructed to characterize plants under full irrigation using the mean values of those that received 100% WR throughout the cycle.

Mean comparisons of VI values among irrigation strategies were performed using Tukey’s test at a 5% probability level. Interpretation values were classified based on the frequency of evaluations that exhibited statistically significant differences between WR levels, as determined by Tukey’s test.

All statistical analyses were conducted using MS Excel 2021, RStudio 9.3, and ASSISTAT 7.7 software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Correlation analysis of vegetation indices

The Pearson correlation matrix (Figure 3A) indicates that in E1, none of the vegetation indices (VIs) correlated with water replacement levels (WRs). In E2 (Figure 3B), several VIs distinguished water deficit (WD), including NDVI, EVI, GNDVI, OSAVI, ExG, NGRDI, VARI, and GLI. Among the visible spectrum indices (VSVIs), VARI and GLI exhibited the highest correlation values (0.970 and 0.990, respectively). Among the multispectral indices (MSVIs), NDVI demonstrated the strongest correlation (0.980).

Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) between vegetation indices and water replacement (% ETc) at the E1 (A), E2 (B), E3 (C), and E4 (D) stages of the corn crop. *: significant at p ≤ 0.05; **: significant at p ≤ 0.01 between water replacement (% ETc) and vegetation indices.

In E3 (Figure 3C) and E4 (Figure 3D), no significant correlations were observed between any of the indices and WRs. These findings suggest that GLI and NDVI were the most responsive VIs within their respective classifications.

The correlation coefficients (r) between WR and vegetation indices (VIs) (Figure 3) ranged from -0.870 (NGRDI in E1) to 0.990 (GLI in E2). Zhang et al. (2021), using stomatal conductance as a reference for WD, reported a maximum correlation of 0.640 with NDVI and a minimum of -0.640 with TOSAVI. Based on these variations in r values, we infer that VIs are more effective in distinguishing different irrigation depths than in estimating stomatal conductance, even though stomatal conductance is influenced by variations in water availability.

Furthermore, our findings confirm that NDVI not only characterizes WR variations but also establishes significant correlations with physiological responses related to plant water status (Zhang et al., 2021). Among the indices analyzed, GLI exhibited the best overall performance, aligning with Becker et al. (2020), who highlighted its high sensitivity to corn leaf chlorophyll content, making it responsive to water and nitrogen (N) stress. Among the multispectral indices, NDVI and OSAVI demonstrated the highest correlation values, reinforcing their reliability for monitoring corn water status compared to thermal indices (Andrade Junior et al., 2021; Cheng et al., 2022).

The vegetative growth stage (E2) demonstrated the highest accuracy, with most of the VIs being responsive to WD. This stage marks the peak of vegetative development, during which the plant allocates most of its biomass to stems and leaves. Consequently, WD at this stage alters pigment concentrations, making it the most sensitive phase for detecting water stress (Sah et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021; Chaves et al., 2023). These results suggest that E2 is the optimal stage for assessing corn water status using VIs.

Early aerial surveys during E1 may be impractical due to crop size, necessitating lower-altitude flights or higher-resolution cameras. In this study, E3 and E4 correspond to the transition from vegetative growth to senescence. At this stage, chlorophyll content declines, masking the spectral manifestations of WD. Becker et al. (2020) observed similar challenges when distinguishing water stress from nitrogen deficiency in corn, as both stresses produced overlapping spectral signatures during senescence. Additionally, WD during the reproductive phase primarily affects grain production, exerting minimal influence on leaf color (Comas et al., 2019).

NDVI and GLI values obtained in E2 (Figures 4A and 4B) were significant at the 1% probability level in the linear regression model. The estimated NDVI values for WR levels of 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% were 0.756, 0.812, 0.868, 0.924, and 0.980, respectively. For GLI, the estimated values were 0.103 (20% WR), 0.133 (40% WR), 0.163 (60% WR), 0.193 (80% WR), and 0.223 (100% WR).

NDVI values increased linearly with WR, with each 1% increase in WR between 20% and 100% resulting in an approximate 0.40% increase in the index (Figure 4A).

NDVI (A) and GLI (B) values for corn plants at vegetative growth (E2) as a function of water replacement. **: significant at p ≤ 0.01.

Similarly, the mathematical model fitted for GLI as a function of WR levels estimates a unit increase of approximately 2.05% within the evaluated WR range (Figure 4B). NDVI demonstrated a broader range for interpreting and classifying WD levels compared to GLI.

The increase in VI values corresponds to a reduction in WD levels, as higher soil water content enhances stomatal conductance and relative leaf water content, subsequently increasing the concentration of various leaf pigments. This process improves the spectral responsiveness of plants (Jensen, 2007; Lopes et al., 2024).

Temporal dynamics of vegetation indices

Figure 5A illustrates the temporal behavior of NDVI in fully irrigated plants, revealing fluctuations throughout the crop cycle. In the first evaluation (14 DAE), NDVI was 0.841, increasing thereafter and stabilizing between 0.920 (63 DAE) and 0.965 (42 DAE). The index only dropped below 0.900 in the final evaluation (70 DAE), reaching 0.871.

Behavior of the vegetation indices NDVI (A) and GLI (B) in corn plants under full irrigation.

A similar trend was observed for GLI (Figure 5B). Initially, at 14 DAE, GLI was 0.136, peaking at 0.213 at 42 DAE, after which it gradually declined to 0.142 at 70 DAE.

The decline in average VI values throughout the crop cycle corresponds to the transition of corn plants into the physiological maturity stage, followed by senescence (Ribeiro et al., 2017). According to Guo et al. (2022), this phase is characterized by reduced biomass synthesis as nutrients are reallocated from vegetative tissues to reproductive structures to support grain filling. This period is also marked by a decline in photosynthetic activity, typically reflected in decreasing VI values.

Similarly, Ribeiro et al. (2017) and Tamás et al. (2023) observed reductions in vegetation indices during the transition from vegetative to maturity stages in corn crops. These results support the present findings and further explain why VIs (Figure 3) were ineffective in detecting WD when applied at the flowering (E3) and physiological maturity (E4) stages.

Classification

The comparison test of mean values obtained from the flight conducted in E1 (Figures 6A and 6B) indicated that spectral indices were ineffective for monitoring WD at this stage of corn development. None of the VIs were able to statistically distinguish the irrigation treatments, as determined by Tukey’s test at a 5% probability level. Conversely, during E2, both indices successfully differentiated variations in irrigation depth levels based on spectral responses, revealing significant statistical differences between treatments (Figures 6C and 6D).

Except for the observation at 14 DAE, in all other evaluations, the highest NDVI values were recorded under full irrigation (100% ETc) (Figure 6C), while the lowest values were observed under the most severe WD (20% ETc). However, NDVI was unable to distinguish between WRs of 80% and 100%, as the index values at 80% ETc were statistically similar to the control treatment. Despite this, in all evaluated periods, NDVI effectively differentiated WRs of 20% and 40% from the higher WR levels of 80% and 100%, as statistically significant differences were detected. The WRs of 20% and 40% differed statistically in three of the five evaluations during E2, while the WR of 60% showed significant differences from all other treatments throughout the period (Figure 6C).

NDVI and GLI values as a function of water replacement during E1 (A and B) and E2 (C and D) at diverse days after emergence (DAE). *Evaluation before treatment application. Different letters denote significant differences by Tukey’s test at 5% probability among water replacement levels on the same day.

In contrast, GLI (Figure 6D) did not exhibit statistically significant differences between the most severe WD levels (WRs of 20% and 40%) in E2. At 60% WR, GLI displayed an inconsistent trend, statistically aligning with both the higher WRs (80% and 100%) and the lower WRs (20% and 40%). In the final aerial survey of E2 (45 DAE), GLI under full irrigation was statistically different from all other treatments. Except for the evaluations at 14 and 21 DAE, GLI values were consistently higher under full irrigation (100% ETc) and lowest under severe WD (20% ETc).

Tukey's test (p ≤ 0.05) revealed that in E3 (Figures 7A and 7B) and E4 (Figures 7C and 7D), NDVI and GLI values were statistically similar, despite variations in water availability.

NDVI and GLI values as a function of water replacement during E3 (A and B) and E4 (C and D) at diverse days after emergence (DAE). *Evaluation before treatment application. Different letters denote significant differences by Tukey’s test at 5% probability among water replacement levels on the same day.

NDVI effectively distinguished WRs of 20% and 40% ETc in 60% of the evaluations. In the classification of index values in E2 (Figure 6C) concerning the degree of WD, these WR levels correspond to severe deficit (80% WD) and severe deficit (60% WD), respectively.

Since NDVI values for WRs of 80% and 100% ETc did not differ statistically, these treatments can be grouped into a single category, representing mild deficit (WD of 20%) or full irrigation (WD of 0%). The WR of 60% ETc is classified as medium deficit (WD of 40%), as this treatment exhibited statistically significant differences from all other treatments.

Thus, classifying the water supply level of corn plants based on NDVI values obtained from the arithmetic mean of the first five aerial surveys (21, 28, 35, 42, and 45 DAE) allows the following classification of irrigation treatments: 1) severe deficit: 0.000 ≤ NDVI ≤ 0.755, 2) critical deficit: 0.756 ≤ NDVI ≤ 0.802, 3) medium deficit: 0.803 ≤ NDVI ≤ 0.875, 4) mild deficit or full irrigation: 0.876 ≤ NDVI ≤ 1.000 (slight deficit or absence).

These NDVI value ranges differ from the general classification for orbital images proposed by Berhan et al. (2011), where values above 0.600 indicate vegetation cover without WD. This discrepancy highlights the importance of crop-specific research to develop more precise and conclusive interpretation frameworks for assessing plant hydration status using vegetation indices.

The data in Figure 6D indicate that GLI values for WRs of 20% and 40% ETc represent a single class: severe deficit (WD of 60%–80%). Additionally, GLI values for WRs of 80% and 100% ETc did not differ statistically in 80% of the evaluated days, converging into the mild deficit (WD of 20%) or full irrigation (WD of 0%) category. The WR of 60% ETc provided GLI values that were statistically similar to those of the 80% and 100% ETc WRs in most images (80%).

Based on these findings, the classification of corn plant hydration status using GLI is simplified into two classes: deficit: 0.000 ≤ GLI ≤ 0.157 and mild deficit or full irrigation: 0.158 ≤ GLI ≤ 1.000.

These results indicate that the multispectral index (NDVI) outperformed the visible spectrum index (GLI) in classification accuracy. This finding aligns with Zhang et al. (2021), who reported that multispectral vegetation indices (MSVIs) are more sensitive to water stress in corn crops, making them more reliable for estimating water availability under field conditions.

Yield prediction

The different WR levels applied exclusively during E2 had a significant impact (p ≤ 0.05) on the analyzed productivity variables. As demonstrated in the correlation studies (Figure 3), these changes exhibited an increasing linear trend concerning the spectral indices obtained for each water supply level evaluated (Figure 8).

NDVI and GLI values in corn plants at the E2 vegetative stage as a function of final dry biomass - FDB (Mg ha-1) (A and B) and total yield of husked green corn ears - TY (Mg ha-1) (C and D). **: significant at p ≤ 0.01.

These results reinforce the findings of Sah et al. (2020), confirming that grain and biomass productivity are directly influenced by water stress.

In Figure 8A, the estimated values for FDB ranged from 13.74 to 31.17 Mg ha⁻1, corresponding to NDVI values of 0.676 (WR of 20% ETc) and 0.960 (WR of 100% ETc), respectively. Similarly, estimated total green ear yield (PT) concerning the same minimum and maximum NDVI values (Figure 8C) ranged from 8.90 to 20.02 Mg ha⁻1.

When estimating FDB using the GLI index (Figure 8B), FDB values ranged from 14.57 Mg ha⁻1 (GLI of 0.107 at WR of 20%) to 32.49 Mg ha⁻1 (GLI of 0.219 at WR of 100%). PT, in correlation with GLI (Figure 8D), exhibited values ranging from 9.38 to 20.92 Mg ha⁻1.

Analysis of the determination coefficients (R2) in Figure 8 indicates that NDVI had greater accuracy in estimating FDB (R2 = 0.983) and PT (R2 = 0.981) compared to GLI, which presented R2 values of 0.959 and 0.975, respectively, for the same variables. These results align with the findings of Sunoj et al. (2021), who also reported greater efficiency of NDVI in estimating productivity, as well as the superior performance of indices incorporating near-infrared (NIR) reflectance compared to those based solely on the visible spectrum. Our findings further validate the effectiveness of RPA-derived imaging for productivity estimation, reinforcing the conclusions of Feizolahpour et al. (2023), Shao et al. (2023), and Leitão et al. (2023), supporting this approach as a valuable tool for corn management.

Additionally, we observed that WD in E2 led to a reduction in final productivity, even when water requirements were fully met in E1 and full irrigation was restored in E3 and E4. This period proved effective for productivity prediction, corroborating previous studies such as Bertolin et al. (2017), which emphasized that images captured during the peak vegetative stage of the crop tend to yield more accurate productivity estimates.

Table 4 presents the classification of GLI values and the variation in productivity as a function of spectral behavior in E2 for the FDB and PT variables, as estimated using the mathematical models in Figures 8B and 8D.

Classification of GLI values at different water deficit (WD) levels from V4 to VT corn stages and estimated final dry biomass (FDB) and total yield of green husked ears (TY) at R4.

Table 5 presents the classification of WD levels in E2 based on NDVI and its predicted impact on final crop productivity, using yield estimates derived from the mathematical models in Figures 8A and 8C.

Classification of NDVI values at different water deficit (WD) levels from V4 to VT corn stages and estimated final dry biomass (FDB) and total yield of green husked ears (TY) at R4.

Calibrating productivity prediction models using NDVI and GLI spectral indices, measured from V4 to VT stages (Figure 8) and classified in Tables 4 and 5, allows for evaluating corn crop water status in the field. This approach enables early prediction of how soil water availability fluctuations may impact crop productivity.

Notably, applying the proposed classification to cultivation conditions differing from those in this study may result in inaccuracies. This is primarily due to the wide genetic variability among commercially available corn genotypes, which exhibit different tolerance levels to WD. Additionally, variations in the duration of phenological stages and the overall crop cycle may influence the applicability of the classification.

Another limitation of this study is that evaluations were conducted within a single crop cycle. This may affect the consistency and robustness of the data, particularly given the potential influence of environmental and temporal variations on spectral responses and crop productivity.

Nevertheless, we believe that the proposed classification will be more precise when applied under soil and climatic conditions characteristic of the Brazilian semiarid region. However, this also underscores the need for further validation studies to extend these findings to environmentally contrasting regions and/or different genetic materials.

CONCLUSIONS

RPA imagery-derived vegetation indices proved to be effective for assessing water conditions and yield prediction in corn crops. NDVI and GLI were particularly effective in detecting water deficit and predicting green ear and biomass yields during vegetative growth. Thus, this stage is ideal for monitoring crop water status using RPA-based remote sensing systems.

Our vegetation index classification offers a precise strategy for semi-arid conditions, enabling reliable water stress diagnosis in hybrid corn AG 1051 via aerial imaging and improved irrigation management. However, these findings may not extend to other cropping scenarios.

Future studies will be crucial to improve the accuracy and applicability of the proposed methodology. This can be done by replicating the experiment across diverse genotypes, soil types, and climatic conditions over multiple crop cycles, as well as by exploring alternative statistical approaches for data analysis and interpretation.

REFERENCES

- Allen, R. G., Pereira, L. S., Raes, D., & Smith, M. (1998). Crop evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements. FAO Irrigation and Drainage.

-

Andrade Junior, A. S. D., Bastos, E. A., Sousa, C. A. F. D., Casari, R. A. D. C. N., &Rodrigues, B. H. N. (2021). Water status evaluation of maize cultivars using aerial images. Revista Caatinga, 34, 432-442. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-21252021v34n219rc

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-21252021v34n219rc -

Barrero, O., Perdomo, S. A. (2018). RGB and multispectral UAV image fusion for Gramineae weed detection in rice fields. Precision agriculture, 19, 809-822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-017-9558-x

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-017-9558-x -

Basso, M., Stocchero, D., Ventura Bayan Henriques, R., Vian, A. L., Bredemeier, C., Konzen, A. A., & Pignaton de Freitas, E. (2019). Proposal for an embedded system architecture using a GNDVI algorithm to support UAV-based agrochemical spraying. Sensors, 19(24), 5397. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19245397

» https://doi.org/10.3390/s19245397 -

Becker, T., Nelsen, T. S., Leinfelder-Miles, M., Lundy, M. E. (2020). Differentiating between nitrogen and water deficiency in irrigated maize using a UAV-based multi-spectral camera. Agronomy, 10(11), 1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10111671

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10111671 -

Bendig, J., Yu, K., Aasen, H., Bolten, A., Bennertz, S., Broscheit, J., & Bareth, G. (2015). Combining UAV-based plant height from crop surface models, visible, and near infrared vegetation indices for biomass monitoring in barley. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 39, 79-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2015.02.012

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2015.02.012 - Berhan, G., Hill, S., Tadesse, T., Atnafu, S. (2011). Using satellite images for drought monitoring: a knowledge discovery approach. Journal of Strategic Innovation and Sustainability, 7(1), 135-153.

-

Bertolin, N. O., Filgueiras, R., Venancio, L. P., Mantovani, E. C. (2017). Predição da produtividade de milho irrigado com auxílio de imagens de satélite. Revista Brasileira de Agricultura Irrigada, 11(4), 1627. https://doi.org/10.7127/rbai.v11n400567

» https://doi.org/10.7127/rbai.v11n400567 -

Burns, B. W., Green, V. S., Hashem, A. A., Massey, J. H., Shew, A. M., Adviento-Borbe, M. A. A., & Milad, M. (2022). Determining nitrogen deficiencies for maize using various remote sensing indices. Precision Agriculture, 23(3), 791 - 811. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-021-09861-4

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-021-09861-4 - Cardoso, P. V., da Silva Seabra, V., Xavier, R. A., Rodrigues, E. M., & Gomes, A. S. (2021). Mapeamento de Áreas de Caatinga Através do Random Forrest: Estudo de caso na Bacia do Rio Taperoá. Revista Geoaraguaia, 11, 55-68.

-

Chaves, A. R. D., Moraes, L. G., Montaño, A. S., da Cunha, F. F., & Theodoro, G. D. F. (2023). Analysis of Principal Components for the Assessment of Silage Corn Hybrid Performance under Water Deficit. Agriculture, 13(7), 1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13071335

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13071335 -

Cheng, M., Jiao, X., Liu, Y., Shao, M., Yu, X., Bai, Y., & Jin, X. (2022). Estimation of soil moisture content under high maize canopy coverage from UAV multimodal data and machine learning. Agricultural Water Management, 264, 107530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2022.107530

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2022.107530 -

Comas, L. H., Trout, T. J., DeJonge, K. C., Zhang, H., Gleason, S. M. (2019). Water productivity under strategic growth stage-based deficit irrigation in maize. Agricultural water management, 212, 433-440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2018.07.015

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2018.07.015 -

Daughtry, C. S., Walthall, C. L., Kim, M. S., De Colstoun, E. B., & McMurtrey Iii, J. E. (2000). Estimating corn leaf chlorophyll concentration from leaf and canopy reflectance. Remote sensing of Environment, 74(2), 229-239. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(00)00113-9

» https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257 -

Feizolahpour, F., Besharat, S., Feizizadeh, B., Rezaverdinejad, V., Hessari, B. (2023). An integrative data-driven approach for monitoring corn biomass under irrigation water and nitrogen levels based on UAV-based imagery. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 195(9), 1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-023-11697-6

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-023-11697-6 -

Gitelson, A. A., Kaufman, Y. J., Stark, R., Rundquist, D. (2002). Novel algorithms for remote estimation of vegetation fraction. Remote sensing of Environment, 80(1), 76-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(01)00289-9

» https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257 -

Gitelson, A. A., Viña, A., Ciganda, V., Rundquist, D. C., Arkebauer, T. J. (2005). Remote estimation of canopy chlorophyll content in crops. Geophysical research letters, 32(8), L08403. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL022688

» https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL022688 -

Guo, X., Li, G., Ding, X., Zhang, J., Ren, B., Liu, P., & Zhao, B. (2022). Response of leaf senescence, photosynthetic characteristics, and yield of summer maize to controlled-release urea-based application depth. Agronomy, 12(3), 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12030687

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12030687 -

Ihuoma, S. O., Madramootoo, C. A. (2019). Sensitivity of spectral vegetation indices for monitoring water stress in tomato plants. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 163, 104860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2019.104860

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2019.104860 - Jensen, J. R. (2007). Remote sensing of the environment: an earth resource perspective. Pearson Prentice Hall.

-

Kim, D. W., Yun, H. S., Jeong, S. J., Kwon, Y. S., Kim, S. G., Lee, W. S., & Kim, H. J. (2018). Modeling and testing of growth status for Chinese cabbage and white radish with UAV-based RGB imagery. Remote Sensing, 10(4), 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10040563

» https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10040563 -

Leitão D. A. H. S., Sharma, A. K., Singh, A., Sharma, L. K. (2023). Yield and plant height predictions of irrigated maize through unmanned aerial vehicle in North Florida. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 215, 108374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2023.108374

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2023.108374 -

Lopes, A. D. S., Andrade, A. S. D., Bastos, E. A., Sousa, C. A. D., Casari, R. A. D. C., Moura, M. S. D. (2024). Assessment of maize hybrid water status using aerial images from an unmanned aerial vehicle. Revista Caatinga, 37, e11701. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-21252024v3711701rc

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-21252024v3711701rc -

Misra, G., Cawkwell, F., Wingler, A. (2020). Status of phenological research using Sentinel-2 data: A review. Remote Sensing, 12(17), 2760. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12172760

» https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12172760 -

Oliveira, A. J., da Silva, G. F., da Silva, G. R., dos Santos, A. A. C., Caldeira, D. S. A., Vilarinho, M. K. C., & de Oliveira, T. C. (2020). Potencialidades da utilização de drones na agricultura de precisão. Brazilian Journal of Development, 6(9), 64140-64149. https://doi.org/10.34117/bjdv6n9-010

» https://doi.org/10.34117/bjdv6n9-010 -

Paolinelli, A., Dourado Neto, D., Mantovani, E. C. (2022). Agricultura irrigada no Brasil: Ciência e tecnologia. Escola Superior de Agricultura Luiz de Queiroz. https://doi.org/10.11606/9786587391236

» https://doi.org/10.11606/9786587391236 -

Ribeiro, R. B., Filgueiras, R., Ramos, M. C. A., de Almeida, L. T., Generoso, T. N., & Monteiro, L. I. B. (2017). Variabilidade espaço-temporal da condição da vegetação na agricultura irrigada por meio de imagens SENTINEL-2a. Revista Brasileira de Agricultura Irrigada, 11, 1884 - 1893. https://doi.org/10.7127/RBAI.V11N600648

» https://doi.org/10.7127/RBAI.V11N600648 -

Roth, R. T., Chen, K., Scott, J. R., Jung, J., Yang, Y., Camberato, J. J., & Armstrong, S. D. (2023). Prediction of Cereal Rye Cover Crop Biomass and Nutrient Accumulation Using Multi-Temporal Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Based Visible-Spectrum Vegetation Indices. Remote Sensing, 15(3), 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15030580

» https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15030580 -

Sah, R. P., Chakraborty, M., Prasad, K., Pandit, M., Tudu, V. K., Chakravarty, M. K., Moharana, D. (2020). Impact of water deficit stress in maize: Phenology and yield components. Scientific reports, 10(1), 2944. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59689-7

» https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59689-7 -

Santos, W. D. O., Medeiros, J. F., Moura, M. S. B., Nunes, R. (2014). Coeficientes de cultivo e necessidades hídricas da cultura do milho verde nas condições do Semiárido brasileiro. Irriga, 19(4), 559-572. https://doi.org/10.15809/irriga.2014v19n4p559

» https://doi.org/10.15809/irriga.2014v19n4p559 -

Shao, G., Han, W., Zhang, H., Zhang, L., Wang, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Prediction of maize crop coefficient from UAV multisensor remote sensing using machine learning methods. Agricultural Water Management, 276, 108064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2022.108064

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2022.108064 -

Silva, S., Sousa, A. C. P., Silva, C. S., Araújo, E. R., Soares, M. A. S., Teodoro, I. (2021). Parâmetros produtivos do milho sob déficit hídrico em diferentes fases fenológicas no semiárido brasileiro. Irriga, 1(1), 30-41. https://doi.org/10.15809/irriga.2021v1n1p30-41

» https://doi.org/10.15809/irriga.2021v1n1p30-41 -

Sunoj, S., Cho, J., Guinness, J., van Aardt, J., Czymmek, K. J., & Ketterings, Q. M. (2021). Corn grain yield prediction and mapping from Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) multispectral imagery. Remote Sensing, 13(19), 3948. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13193948

» https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13193948 -

Tamás, A., Kovács, E., Horváth, É., Juhász, C., Radócz, L., Rátonyi, T., & Ragán, P. (2023). Assessment of NDVI dynamics of maize (Zea mays L.) and its relation to grain yield in a polyfactorial experiment based on remote sensing. Agriculture, 13(3), 689. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13030689

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13030689 -

Zhang, L., Han, W., Niu, Y., Chavez, J. L., Shao, G., & Zhang, H. (2021). Evaluating the sensitivity of water stressed maize chlorophyll and structure based on UAV derived vegetation indices. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 185, 106174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106174

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106174

-

FUNDING:

The authors would like to thank the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for funding the scientific initiation scholarships (PIBIC).

Edited by

-

Area Editor:

Lucas Rios do Amaral

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

17 Mar 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

24 May 2024 -

Accepted

23 Jan 2025

ENHANCED WATER MONITORING AND CORN YIELD PREDICTION USING RPA-DERIVED IMAGERY

ENHANCED WATER MONITORING AND CORN YIELD PREDICTION USING RPA-DERIVED IMAGERY