Abstract

Objective to characterize how the nursing process is applied in the Indigenous Health House, identifying the challenges, adaptations, and strategies necessary to integrate indigenous peoples’ cultural and ethnic specificities.

Method a qualitative, descriptive, and exploratory study conducted between January and March 2022 in an Indigenous Health House within the Guamá-Tocantins Special Indigenous Health District, Brazil. Semi-structured interviews and content analysis were used.

Results thirteen professionals participated, including four clinical nurses and nine nursing technicians. Eight self-identified as mixed race, four as indigenous, belonging to four distinct ethnicities (Wai-Wai, Gavião, Munduruku, and Amanayé), and one as black. Emerging topics emerged regarding the nursing process organization and challenges, resulting in three categories: The nursing process in indigenous health: organization and challenges; Intercultural care in nursing practice; and Nursing team care singularities.

Final considerations and implications for practice there is a superficial alignment between intercultural care and the biomedical model, revealing a gap in the direct relationship among elements highlighted in indigenous health conferences, nursing processes, and curricular guidelines. This underscores the importance of strategies that effectively integrate the cultural and ethnic specificities of indigenous peoples into practice.

Keywords:

Cultural Diversity; Health Services; Indigenous Peoples; Nursing; Nursing Process

Resumo

Objetivo caracterizar como o processo de enfermagem é aplicado na Casa de Saúde Indígena, identificando os desafios, as adaptações e as estratégias necessárias para integrar as especificidades culturais e étnicas dos povos indígenas.

Método pesquisa qualitativa, descritiva e exploratória, realizada entre janeiro e março de 2022 em uma Casa de Saúde Indígena do Distrito Sanitário de Saúde Indígena Guamá-Tocantins, Brasil. Utilizaram-se entrevista semiestruturada e análise de conteúdo.

Resultados participaram 13 profissionais, sendo quatro enfermeiros assistenciais e nove técnicos de enfermagem. Oito se autodeclaram pardos, sendo quatro indígenas pertencentes a quatro etnias distintas (Wai-Wai, Gavião, Munduruku e Amanayé) e um negro. Surgiram temas emergentes sobre a organização e os desafios do processo de enfermagem que resultaram em três categorias: O processo de enfermagem na saúde indígena: organização e desafios; Cuidado intercultural na atuação da enfermagem; e Singularidades dos cuidados da equipe de enfermagem.

Considerações finais e implicações para a prática há um alinhamento superficial entre o cuidado intercultural e o modelo biomédico como déficit da relação direta entre elementos sinalizados nas conferências de saúde indígena, processos de enfermagem e diretrizes curriculares, destacando a importância de estratégias que integrem as especificidades culturais e étnicas dos povos indígenas efetivamente na prática.

Palavras-chave:

Diversidade Cultural; Enfermagem; Povos Indígenas; Processo de Enfermagem; Serviços de Saúde

Resumen

Objetivo caracterizar cómo se aplica el proceso de enfermería en la Casa de Salud Indígena, identificando desafíos, adaptaciones y estrategias para integrar las especificidades culturales y étnicas de los pueblos indígenas.

Método investigación cualitativa, descriptiva y exploratoria, realizada entre enero y marzo de 2022 en una Casa de Salud Indígena del Distrito Sanitario Especial Indígena Guamá-Tocantins, Brasil. Se realizaron entrevistas semiestructuradas y análisis de contenido.

Resultados participaron trece profesionales, entre ellos cuatro enfermeros clínicos y nueve técnicos de enfermería. Ocho se autoidentificaron como mestizos, cuatro como indígenas pertenecientes a cuatro etnias distintas (Wai-Wai, Gavião, Munduruku y Amanayé), y uno como negro. Surgieron temas emergentes sobre la organización y los desafíos del proceso de enfermería, que dieron lugar a tres categorías: El proceso de enfermería en la salud indígena: organización y desafíos; Atención intercultural en la práctica enfermera; y Singularidades de la atención del equipo de enfermería.

Consideraciones finales e implicaciones para la práctica existe una alineación superficial entre el cuidado intercultural y el modelo biomédico, con déficit en la relación directa entre elementos señalados en conferencias de salud indígena, procesos de enfermería y directrices curriculares. Se destaca la importancia de estrategias que integren efectivamente las especificidades culturales y étnicas de los pueblos indígenas en la práctica profesional.

Palabras clave:

Diversidad Cultural; Enfermería; Proceso de Enfermería; Pueblos Indígenas; Servicios de Salud

INTRODUCTION

The right of indigenous peoples to health is provided for in the Federal Constitution of 1988, ratified in Law 9,836/1999 (Arouca Law), through the creation of the Indigenous Health Care Subsystem (In Portuguese, Subsistema de Atenção à Saúde Indígena - SASISUS) and the Brazilian National Policy for Healthcare for Indigenous Peoples (In Portuguese, Política Nacional de Atenção da Saúde dos Povos Indígenas - PNASPI).1 PNASPI highlights the need for differentiated healthcare according to the cultural, epidemiological and operational specificities observed in indigenous territories, supporting other legal frameworks.1,2 Brazilian indigenous social control3 provides opportunities for debate, ensuring broad, comprehensive and autonomous care that respects specific aspects and meets the ethnic-geographical demands of each people and territory.3,4

Indigenous peoples are included in the Brazilian Health System (In Portuguese, Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS) through Primary Health Care (PHC), carried out in villages, organized by Special Indigenous Health Districts (In Portuguese, Distritos Sanitários Especiais Indígenas - DSEI).1,2 DSEIs offer health and support services exclusively for Indigenous people on the move: the Indigenous Health Support Houses (In Portuguese, Casas de Apoio à Saúde Indígena - CASAI), which provide support and shelter for hospital and polyclinic care in urban centers. This flow is supported by a multidisciplinary indigenous health team (MIHT), with the participation of various professionals, including indigenous and non-indigenous nurses and the indigenous health worker (IHW).5,6

In MIHT, there is a significant presence of nursing professionals.5,7 At CASAI, this presence is fundamental, with their work process being directed towards the care provided, observing the particularities of ethnic groups, in dialogue with the biomedical model5 , as recommended in PNAISPI.2,3 However, there are challenges identified in the different CASAI scenarios that affect their performance, such as deficits in infrastructure, intercultural training, indigenous medicine,3,5,6 in addition to limitations in the Brazilian National Curricular Guidelines for the Undergraduate Nursing Course (In Portuguese, Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do Curso de Graduação em Enfermagem - DCN/Enf).8

DCN/Enf have made little progress in regional specificities, unlike the guidelines defined in PNASPI,7,8 which is fundamental for the work process to meet intercultural training.1,2 There are limitations in the systems that nursing professionals experience5,6 which point to the need for adjustments in training7,9 for culturally safe work10,11 through continuing education in the aforementioned area.9

It is essential that this discussion addresses the nursing process (NP). NP is the system used by nursing professionals to ensure quality care centered on patient needs. NP should be studied in this specific context, as it provides a new perspective on Basic Human Needs (BHN)12 and consists of five interrelated stages: nursing assessment; nursing diagnosis; nursing planning; nursing implementation; and nursing development.12,13

In the literature, the topic of NP and indigenous health has a significant gap, considering the different realities observed, the ethnicities that are served at CASAI and the adaptation of flows and instruments.14 Studies on this scenario focus on observed realities, nurses’ performance, and the challenges of intercultural practices. On the other hand, further studies on adapted NP are needed to respect and integrate the cultural, social, and regional specificities of the populations assisted in healthcare services.4-7

This cultural integration is evident internationally, which presents similar challenges. Research demonstrates significant progress in integrating culturally safe practices into education and work with indigenous peoples. Experiences with Indigenous peoples in Canada have identified that systemic barriers persist in primary care.15 In another study, conducted in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States, it was shown that cultural safety interventions for healthcare professionals demonstrate systemic limitations, the need for policy changes16 and interventions for shared health decision-making.17

In this regard, considering the specificities and aggregating care dynamics, intercultural care1,2 and the pertinent role of nursing in this area,7 the question arises as to how ethnic diversity and nursing responsibilities are being addressed in nursing processes. From this perspective, despite the normative advances of PNASPI, there is great difficulty in strengthening the differentiated way of caring for indigenous peoples from a cultural and ethnic perspective.5 It is necessary to identify how nursing professionals act through their science12 and many cultural realities.5-7

In the current context, in which cultural diversity must be recognized and valued in healthcare services, this study becomes particularly relevant, providing support for nursing guidelines.8 According to Resolution 736/2024 of the Federal Nursing Council (In Portuguese, Conselho Federal de Enfermagem - COFEN), the implementation of NP in diverse socio-environmental settings requires critical reflection on the training of healthcare professionals to act in culturally safe ways.11

In this context, the question is: how are the cultural and ethnic specificities of Indigenous peoples incorporated by nursing teams in NP developed at CASAI? And what are the main challenges and strategies for effective intercultural practice? Therefore, this work seeks to contribute to the improvement of nursing practices, promoting more inclusive and effective care at CASAI, discussing the guidelines with DCN/Enf and meeting PNASPI, with opportunities for inclusive and adapted training for Indigenous and non-Indigenous nurses.15

Although Indigenous health5-7,9 and NP12 are widely discussed topics in the literature, this study proposes an innovative perspective by articulating these two fields. Despite efforts to incorporate culturally adapted practices in the care of Indigenous peoples15-17 , regarding the roles of nursing,18 there are no adaptations in the application of NP in these contexts. By focusing on the adaptations and strategies applied in NP in this context, the study contributes to addressing the remaining gaps in the qualification of differentiated care, particularly critical in Brazil, where CASAIs represent a unique model of care.

This study aimed to characterize how NP is applied at CASAI, identifying the challenges, adaptations, and strategies necessary to integrate the cultural and ethnic specificities of Indigenous peoples.

METHOD

This is a qualitative, descriptive, and exploratory study. The methodological approach followed the COnsolidated for REporting Qualitative research.19 The study setting was the Icoaraci Indigenous Health House of the Guamá-Tocantins (GUATOC) DSEI, located in the municipality of Belém, in the state of Pará, Brazil. The Icoaraci Indigenous Health House is an indigenous health sub-establishment that supports the treatment and monitoring of indigenous users, meeting the needs of medium and high complexity.

The study population consisted of 13 healthcare professionals, including nurses and nursing technicians, all with at least 18 months of experience in Indigenous health and demonstrating openness to dialogue. Participants were selected based on convenience and availability. Nursing professionals who perform technical or care activities at CASAI Icoaraci were included. Professionals without formal ties to the institution or those with significant cognitive impairments that could compromise understanding of the questions and clarity of their answers were excluded, to ensure the reliability of the information collected.

Data collection was conducted on-site between January and March 2022 by an Indigenous nurse from the Tembé ethnic group, under the guidance of a PhD nurse researcher with expertise in the field. During the interviews, the researcher was part of the research group, coordinated by the supervising professor, who conducts research and studies with indigenous peoples. Participants were contacted in person through technical visits to present the project and schedule data collection. Participants knew the interviewer and their reason for conducting the research, and one interview was not completed due to the interviewee’s lack of available time on the day scheduled by participants.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted in person at CASAI, as scheduled, in a private location, without third-party participation, and using a guide instrument. They lasted an average of 30 minutes and were simultaneously recorded on two audio devices. All information was collected and used, and the data saturation technique was not used, as it was decided to work with all professionals available during the collection period, considering the limited population and the census approach within the context of CASAI.

The guide was organized into three units (identification; professional profile; and professional performance) with the following questions: Do you know the importance of NP? Can you distinguish the stages? What precautions are taken in implementing NP? What are the intercultural difficulties faced in implementing NP at CASAI? How do you integrate scientific knowledge with intercultural knowledge? And what are CASAI’s main challenges? There was no need for repetition, and field notes were taken during fieldwork.

For transcription, the Google Docs® text editor was used, using the “voice typing” tool. The transcription was then coded according to professional category, identified with the letter “N,” followed by numbering, specifying the locations of work: CASAI, with the letter “c”; and DSEI, with the letter “d”. Due to the pandemic and access restrictions, transcripts were not returned to participants, and a pilot test was conducted.

It was based on Bardin’s content analysis.20 Microsoft Excel® and Microsoft Word® were used as resources. After the data analysis phase, three thematic categories emerged from the identification and grouping of thematic units emerging from the interviews, enabling an understanding of the interrelationships between care practices and cultural specificities.

As a theoretical contribution, in addition to normative documents such as Resolution 736/2024 of COFEN, DCN/Enf and Wanda Horta’s Theory of Basic Human Needs, the concept of cultural security was adopted,21,22 which represents an evolution as self-determination of indigenous peoples in the context of nursing.

This framework is complemented by the contributions of Gersem Baniwa23 and Rosani Fernandes24 , Indigenous intellectuals who propose a forceful critique grounded in a counter-colonial epistemology that values ancestral knowledge, original cosmologies, and the right to self-determination of Indigenous peoples, essential for thinking about the field of health. Their work, in the fields of education, anthropology, and social sciences, contributes to a broader understanding of the processes of epistemic resistance23,24 and the production of meaning in healthcare.

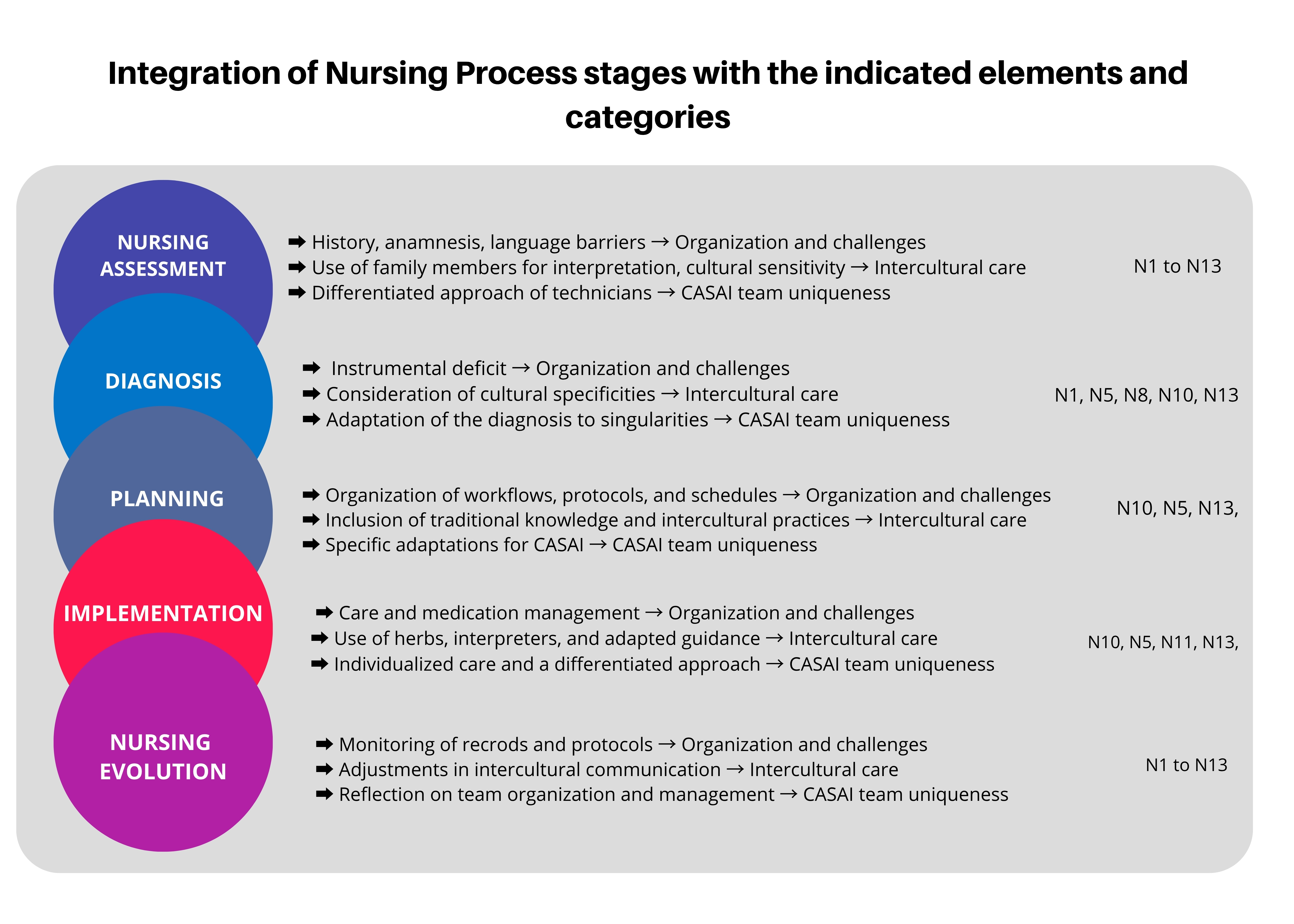

The construction of visual diagrams (Figures 1 and 2) was performed as an integrated stage in data analysis, representing interpretations derived from the emerging categories. For this, Canva Pro was used as a layout support tool. It should be noted that the figures were created based on team consensus but were not validated by participants, which represents a study limitation.

Their ideas engage with the contributions of critical and postcolonial theories by problematizing power asymmetries, epistemicides, and the marginalization of indigenous knowledge in curricula and institutional practices.23,24 This theoretical basis makes it possible to understand the statements not only as individual experiences, but as expressions of resistance, tension and recreation25-27 in the face of the biomedical model hegemony28 , pointing to the need for intercultural care practices committed to equity and cognitive justice.

The research was authorized by DSEI-GUATOC and approved by the Research Ethics Committee, under Opinion 145,936 of 2021. All participants signed the Informed Consent Form, and, to guarantee anonymity, statements were identified by alphanumeric codes.

RESULTS

Thirteen workers participated in the study, four (30.8%) of whom were clinical nurses and nine (69.2%) were nursing technicians. All workers interviewed were female, with a mean age of 38.5 years, ranging from 27 to 55 years. Of these, eight (61.5%) identified as mixed race, four (30.8%) as indigenous, belonging to four distinct indigenous ethnicities (Wai-Wai, Gavião, Munduruku, and Amanayé), and one (7.7%) as black. Regarding educational background, ten interviewees (76.9%) came from private institutions and three (23.1%) from public institutions. In relation to specialization, all nurses have a lato sensu graduate degree in indigenous health and/or public health. Nursing technicians do not have a specialization. Regarding their work in the Indigenous Healthcare Network, six (46.1%) worked in three or more specific locations within the Indigenous Healthcare Network, four (30.8%) worked at CASAI and another Healthcare Network, and three (23.1%) worked only at CASAI.

After the categorization process, professionals’ statements were systematically organized, allowing the identification of emerging themes that reflect, in an interconnected way, the organization and challenges of NP, intercultural care and the singularities of the care provided at CASAI, such as the highlights observed below:

Nursing process in indigenous health: organization and challenges

This category presents discourses on the understanding and importance of NP from the perspective of nursing professionals. According to the interviewees, NP is primarily focused on organized and effective workflow and care, prioritizing holistic treatment in healthcare and prevention, as outlined below:

[...] maintaining work organization, maintaining flow, and being able to better analyze the patient, starting with their history, checking for any problems, making a diagnosis, and keeping daily notes [...] (N5c).

[...] yes, it’s important both in the role of nursing technician and in nurses’ specific records, such as physical examinations, counter-referrals, sending prescriptions to the centers, medication history and checks [...] (N2c).

[...] it’s important to organize medications and work schedules. This becomes so important [...] (N11c).

It was also identified that the interviewees have limitations in the application of NP, as recommended partly by the lack of standardization of the process at CASAI, as well as by the lack of nursing management to promote the organization of this assistance, resulting in mechanical and intuitive actions.

[...] what we do here isn’t much different than what we do on duty, during visits, taking blood pressure, etc. I haven’t noticed much difference between one process and another [...] (N3c).

[...] at CASAI, care is provided by the nursing team’s organization, according to the needs of each Indigenous group, but goals aren’t met due to the lack of nursing management and the demands of the centers and CASAI. We become very overwhelmed with work. As a result, we sometimes fail to provide adequate care to the Indigenous people. If there were nursing management, it would be better. In short, the nursing process would be organization and/or planning [...] (N10c).

[...] the nursing station is limited in care, and administrative management is focused on nursing planning [...] (N13d).

It was also possible to observe that nursing technicians demonstrated difficulty in visualizing their role, both in the exercise of work and in the execution process, related to the difference between indigenous and non-indigenous professional care:

[...] for instance, if you were in the hospital caring for someone who wasn’t your blood relative, what would you feel at that moment? I wanted to feel that it’s very different from your care as a professional and your care as a blood relative, you know, it can be very different. [...] (N9c).

Intercultural care in nursing practice

This category encompasses intercultural care and the challenges it faces. Communication between professionals and Indigenous users stood out, highlighting the plurality of nine ethnic groups: Xikrin; Kayapó; Arara; Parakanã; Munduruku; Tiriyó; Kaxuyanã; Wai-Wai; and Waruete. Of these, the first four ethnic groups present greater communication and language challenges due to linguistic diversity, customs, and habits in interacting with Indigenous and non-Indigenous professionals, as well as the lack of interpreters from their cultures.

[...] the main difficulty is language, especially among the Kaiapó, Xikrin, and Parakanã ethnic groups, especially for female users who don’t speak Portuguese, and we end up relying on relatives who do speak Portuguese [...] (N12d).

[...] in the case of CASAI Icoaraci, user turnover is very high. So, if I only work with one ethnic group daily, I’ll learn, because I’ll only work with one dialect. Now, there are several ethnic groups and turnover, so it’s difficult to understand [...] (N8d).

The high turnover of patients of the most diverse ethnicities was also highlighted as problematic, making communication between professionals and patients difficult, as reinforced in the statement below.

[...] in the case of the Kaiapó ethnic group, we know that they know how to speak Portuguese, but often they don’t want to speak it. So, for those who understand, it’s easy, but for those who don’t understand, who don’t speak, it’s difficult for us to understand [...] (N6c).

Evidence shows that communication difficulties have an impact on adherence to procedures such as cervical screening, endoscopy, colonoscopy, prostate, transvaginal and other examinations, due to linguistic differences and the lack of interpreters who can help these groups participate.

[...] another challenge is trying to show them something basic we do: cervical cancer screening for Indigenous women. Many still don’t accept it. Despite all the work we do, some Indigenous women still resist doing it. So, the challenge is getting them to understand that this is for the betterment of their health and for health; this applies to these basic invasive and hospital procedures. Another challenge we face in this process is that we’re within CASAI, and we have to deal with those who come from the village and receive them for hospital care. They come to the city, many knowing they’re going to have a procedure, and others don’t even know they’re going to have it, but when they get there, they don’t want to have that treatment at the time. So, we have to intervene and try to get them to do it, providing guidance before the procedure [...] (N5c).

Singularities of the care provided by the nursing team at the Indigenous Health Support House

This set refers to the care provided by the nursing team at CASAI. Despite the communication difficulties mentioned in the previous category, the nursing team’s commitment to maintaining a dialogue with intercultural aspects was noted, particularly from Indigenous nursing professionals. They point to the initiative of active listening and the introduction of Indigenous medicine practices, respecting patients’ lifestyles and encouraging co-participatory healthcare.

[...] respect: each indigenous person has their own behavior, habits, perspective, observation, and understanding, respecting cultures. For instance, when it comes to food, there are Indigenous people who don’t eat meat, so we have to respect it. Sometimes they only eat potatoes and yams, not rice or beans; it’s their culture, we have to respect it. The secretariat already says it’s a special department, so we’re professionals, and even I, as an Indigenous person, have to adapt to their system, especially those more indigenous people who live in remote villages [...] (N7d).

[...] yes, we think deeply about customs, from food, hygiene, and clothing—we think deeply about respecting them. It’s different; everyone is different. Some are more affectionate, others less so. Traditional medicine, adapting care and medicinal herbs, incorporating traditional and indigenous knowledge, allowing the use of herbs alongside prescribed medication, and working collaboratively. [...] (N4d).

However, some professionals reported that NP could better meet the unique needs of CASAI patients if there were a clearer redistribution of functions within the nursing team, distinguishing direct care activities — which include planning and executing care by the clinical nurse — from administrative and managerial functions, which should support the supervision, monitoring, and standardization of NP as a whole.

It is worth noting that there is a nursing leadership role in the setting, but according to participants, there is still an accumulation of functions and overload between direct care and administrative demands. This reality highlights the need for more appropriate organizational tools adapted to the ethnocultural diversity of patients, also considering the care already provided in the base centers.

[...] no, distribution of developments with nurses according to schedules and workload, having the necessary instrument to make the nursing diagnosis, having a nursing coordination, because we end up doing both administrative and assistance or having an immediate nursing manager [...] (N5c).

[...] this must be implemented considering the needs of each user, considering the length of stay and absence from healthcare, since the demand for work functions in the CASAI is different and the user profile must be considered, both due to the monitoring already carried out in the CENTERS and the dynamics of the different work assignments [...] (N8c).

The of interviews analysis repeatedly highlighted the challenges of communication due to linguistic and customary diversity, the need to consider cosmologies and spiritual practices as an integral part of indigenous medicine, including care with medicinal herbs and other healing practices, and the lack of nursing management and specific instruments, as shown in Figure 1. These aspects were aligned with the stages of NP, giving rise to Figure 2, which summarizes how the emerging cultural specificities can be incorporated into each stage of NP.

Figure 2 represents the elements highlighted by participants that demonstrate that each stage of NP—from data collection to diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evolution—is integrated with the specificities of Indigenous care. It reflects the need for systematic adaptation of NP to the cultural specificities of local healthcare users, demonstrating how each stage can be adjusted to ensure safe care.

DISCUSSION

The diverse ethnic composition of participants, in addition to characterizing the profile of professionals, constitutes an important part of understanding the central expression of the concept of cultural security21,22 and the need to discuss equity in NP in an indigenous context. This is stated because there is an evolution in the guardianship of indigenous peoples towards awareness, sensitivity and security characterized by the presence of indigenous professionals, in which the self-determination of indigenous peoples is materialized through the sharing of their knowledge, transcending demographic representation and operating as a decolonial strategy23,24 that confronts the historical epistemicide of indigenous peoples.

This converges with Canadian evidence on expanded roles of Indigenous nurses18 as cultural mediators, but diverges regarding systematization. While in Canada, structured protocols29 for cultural mediation are observed, in the Brazilian context of CASAI Icoaraci, this mediation emerges intuitively, dependent on individual sensitivity when it comes to non-Indigenous people, especially.

A fundamental epistemological tension emerges: while there are structured programs, albeit with systemic limitations recognized in the international context16 , the Brazilian scenario reveals an absence of institutionalized protocols, depending on the individual sensitivity of professionals5,7,9 . This paradoxical configuration reflects the persistence of coloniality in institutional practices, in which the lack of systematization perpetuates power asymmetries.24

The significant graduate program in Indigenous health constitutes a compensatory strategy for the curricular gaps identified in undergraduate programs, demonstrating the need for structural curricular transformation. However, this individual compensation does not replace the systemic transformation advocated by PNASPI, demonstrating a subordinated inclusion, where Indigenous professionals are incorporated without questioning hegemonic structures,23,24 especially those related to training.

Regarding the application of nursing science,12,13 it is noted that there is some knowledge about NP, but this is limited when all stages are applied. On the other hand, despite the adversity highlighted above, the results indicate that the CASAI Icoaraci nursing team promotes adaptation of the stages to the multicultural environment.5,6,30 The adaptations observed in the evaluation incorporate cosmologies, ritual practices and indigenous knowledge that configure new professional roles guided by cultural security,21,22 and require redefinition when applied in indigenous contexts, considering the place of belonging of indigenous professionals.24

The valorization of traditions in the first stage of NP constitutes what we call “ontological translation”, a process in which different cosmologies about health and disease dialogue without epistemological hierarchy.23 This translation transcends the collection of biomedical data,28 incorporating counter-colonial epistemologies, in which ancestral knowledge is recognized as valid systems of knowledge.23,24

It converges with experiences in which cultural safety20,21 requires examining the impacts of one’s own professional culture on clinical interactions.11 However, at CASAI, this ontological translation emerges intuitively from the sensitivity of indigenous professionals, highlighting both the potential and the fragility of depending on non-systematized individual initiatives.

In diagnosis, in turn, the stage with the greatest limitations in application, there is a focus on biomedical aspects20,28 and also on cultural perceptions of health and disease6,7 from an Indigenous perspective.4 This reveals a fundamental epistemological conflict between biomedical taxonomies and Indigenous cosmologies. The identified limitations reflect the challenges of multi-epistemic medical pluralism,28 requiring dialogue with historically hierarchical knowledge.

The absence of specific diagnoses for indigenous health perpetuates essentialist perspectives of culture, contrasting with advances in cultural security that guide the development of culturally sensitive taxonomies.11 The intuitive incorporation of Indigenous perceptions by professionals, although promising, lacks systematization in which there is cultural interpretation in the diagnostic stages, in order to break with the persistence of epistemic coloniality,23,24 in which diagnostic instruments remain centered on biomedical rationality.

In planning, the work plan incorporates intercultural and adaptive strategies22 aligned with the concept of cultural safety and equity,11 addressing the BHN according to the customs of their ethnic group, including indigenous practices in the care plan. The signaling of the need for interpreters and/or the application of tools that consider ethnic singularities, and especially to facilitate communication between the MIHT and Indigenous patients, converges with the self-determination of indigenous peoples, due to the orientation towards linguistic equity required24 at CASAI settings.

This reveals that the linguistic diversity of the ethnic groups served by CASAI goes beyond merely communicational issues, reflecting historical power asymmetries.15 The need for interpreters converges with findings on language barriers as a reflection of systemic racism in healthcare services.5,16 It diverges, however, from structured experiences,11 in which cultural mediation is institutionalized through specific professional roles. The adaptation of BHN to ethnic specificities suggests the need to discuss Wanda Horta’s theory to incorporate culturally situated needs into the Brazilian context.

It guides the holistic approach as a strategy for implementing communication, flows and adapted records, mediated by interculturality,31 and demonstrates the importance of PNAISPI, suggesting how differentiated attention is beneficial for service quality.23,24 It confirms that technical care procedures and plans must dialogue with indigenous medicine practices and their technologies,5 making it important to advance the desired intercultural health.32,33,34 It converges with cultural recreation,24 in which indigenous professionals not only reproduce protocols, but also resignify them based on their cosmologies, creating hybrid care technologies.

Regarding nursing evolution, there is a need to include feedback from indigenous people themselves through their worldview4 , with protocols that observe elements such as linguistics, symbols, worldview, cosmology and specific care practices when providing assistance to ethnic groups, in order to reduce the centrality of the biomedical model.35 Incorporation transcends mere consultation and must be determined by indigenous patients themselves, not by professionals,11 reflecting principles of self-determination.24 However, this diverges from the reality observed at CASAI, where evaluation protocols remain centered on biomedical indicators, marginalizing indigenous criteria of therapeutic efficacy.

They must be plural, aligned with the peculiarities of the ethnic groups registered in the CASAI flows, enabling the care provided to be relevant, optimized, respectful and in cooperation and dialogue between the health team and the indigenous communities, implementing what is recommended in PNAISPI.1,2,3 This need converges with co-management models18 and the principles of cultural security,11 which emphasize the power of self-determination of indigenous peoples.24

The implementation of care protocols that incorporate cosmological elements and traditional healing practices, validated jointly with the indigenous communities served, should be a strategy to implement differentiated care in these environments.34 This should also be achieved through the development of specific indicators that measure the effectiveness of integration. This community validation is aligned with principles that recognize the need for equitable partnerships and mechanisms to overcome coloniality in organizational transformation,11 highlighting the need to institutionalize mechanisms to overcome coloniality24 in health practices.

In this sense, continuous and intercultural training is fundamental for understanding cultural specificities5,14,32,35 and addressing health disparities.31 One example is the awareness-raising course on indigenous rights, promoted by pedagogue Rosani Fernandes, in 2015, which targeted non-indigenous professionals, resulting in their greater understanding of the diversity of original cosmologies and worldviews, and in the reduction of discriminatory actions and speech,24 converging with findings on the effectiveness of experiential approaches that increase acceptance of traditional practices.15-17

There are well-developed strategies in the healthcare field. Initiatives by the Universidade Aberta do Sistema Único de Saúde and Universidade de Brasília represent institutionalization efforts that converge with cultural safety training models,17 although they remain fragmented compared to integrated systems observed internationally. The language course taught by Indigenous academics as indigenous professionals provides specific training, as well as experiences with other indigenous populations on cultural safety4,11 and adapted digital health interventions,33 for instance.

However, it is necessary to advance in the inclusion of curricular components with their own workload on the topic of indigenous health, given that Western knowledge and its biomedical model in health do not meet all the needs of indigenous peoples.36 This limitation demonstrates the need for curricular transformation based on equity and social justice,11 in which the transformation is epistemic24 and must transcend the mere inclusion of content.

Furthermore, extension projects at CASAI and research in the area that support the development of technologies,33,34 that map the different realities of CASAI5,6 and that collaborate with nursing diagnoses and the construction of adapted instruments for the evaluation of indigenous people must advance, observing digital technological advances.30 They must incorporate participatory methodologies, aligning with decolonial principles23 and horizontalization of knowledge production relations.

It is also necessary to encounter different knowledges that allow for the incorporation of other epistemologies that address cultural and social aspects,23 which highlight the provision of care based on indigenous medicine,5,23 with the opportunity for the implementation of NP, based on critical and reflective perspectives, and which include interculturality. Linguistic and cultural diversity, for instance, are highlighted by healthcare professionals5,6,14 as challenges to effective communication. The inclusion of interpreters,5,14 indigenous professionals of different ethnicities, is essential for training non-indigenous nurses in different languages and/or developing technologies to support this communication.34

The importance of maintaining indigenous languages23 as a fundamental element in healthcare is highlighted,5,6,34 as well as the values attributed to orality, the driving force of indigenous peoples and an element of understanding their worldviews.23 The different profiles in healthcare services demonstrate the potential of inclusion policies, which have included indigenous people as healthcare professionals, with opportunities for training interpreters or professionals who are fluent in indigenous languages.5,14 This highlights the need to consider diverse productions of ethnoknowledge and the diversity of peoples.24

In the professional practice of nursing, incorporating interculturality fosters an environment of care, supported by COFEN Resolution 736/2024, which recognizes the need to adapt NP to diverse socio-environmental contexts, including respect for Indigenous cultural practices and knowledge. To this end, the dialogue on intercultural care in training must advance to include other epistemologies,23 with an emphasis on studies of Indigenous intellectuals, syllabi, and objectives that address interculturality, diversity, equity, inclusion, ancestry, ethnicity, and other aspects, through a decolonial perspective.23

Still from the perspective of professional practice, other issues have impacted the performance of these professionals. There are significant deficiencies that overburden nursing management, such as a lack of equipment and adequate physical space, as well as formal training in Indigenous languages with a focus on health terminology for the entire team, for the proper recording of cultural elements in NP and joint training of MIHT that incorporate IHW as formal cultural mediators in NP stages. These specific equipment and training needs were highlighted by participants as essential to overcoming the prevailing biomedical model and achieving the effective integration advocated by PNASPI and COFEN Resolution 736/2024.

On the other hand, the new configuration of the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples has pointed to different perspectives, with the coordination of new managers and significant participation of Indigenous voices in different settings.30,35 This institutional restructuring may enable: 1) greater participation of indigenous professionals in DSEI management positions, which facilitates the cultural validation of the proposed nursing instruments; 2) establishment of specific guidelines for adapting NP to ethnic realities; 3) allocation of specific resources for intercultural training of healthcare professionals. These structural changes have the potential to directly impact the operationalization of NP at CASAI, as they establish concrete mechanisms for the integration of technical-scientific nursing knowledge with the ancestral knowledge of indigenous peoples.

Different fronts must advance to strengthen the adapted NP. The participation of professors and researchers initially provides an opportunity to raise awareness and dialogue about the inclusion of content on the topic, with subsequent strengthening of professionals in the field with differentiated perspectives.37 This is in line with the reinterpretation of classics, in order to enable new readings and lenses through which the world is read, starting from indigenous peoples and their belonging.24

Furthermore, interprofessional collaboration is a key component in providing comprehensive care; therefore, interaction between nurses, nutritionists, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals should be encouraged to ensure that the multiple dimensions of patient well-being are considered.5 This strengthens the care provided and promotes a care environment with more complete and contextualized responses,25,27 facilitating the construction of care that truly meets the expectations of PNAISPI.1

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

The results reveal that NP at CASAI integrates technical and intercultural practices to a limited extent. The challenges identified include language barriers and overload resulting from a lack of specific management. Necessary adaptations include detailed records, use of traditional knowledge, and personalized care. Thus, the study highlights the importance of strategies that integrate indigenous peoples’ cultural and ethnic specificities, such as a specific adapted instrument for intercultural anamnesis, culturally sensitive nursing diagnoses, specific protocols developed for each CASAI, and the development of specific translation applications for health terminologies in the languages of the ethnic groups assisted.

This study is limited to analyzing a CASAI scenario related to the ethnicities served and may not reflect other scenarios. Future research could explore the training of indigenous people in undergraduate nursing programs and the effectiveness of intercultural training programs for nurses and other healthcare professionals, assessing their impact on the quality of care and the implementation of a mandatory curriculum component on indigenous health in undergraduate nursing programs. Furthermore, longitudinal studies could examine how the integration of indigenous medicines into nursing practices affects the long-term health and well-being of indigenous populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To the coordinators and technicians of the GUATOC Health District and to Eliene Rodrigues Putira Sacuena, indigenous coordinator of the SASISUS PHC.

-

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

No funding.

DATA AVAILABILITY RESEARCH

The contents underlying the research text are included in the article.

References

-

1 Cerri RA, Garnelo L. O contexto da produção de normativas na implementação da política de saúde indígena. Interface. 2025;29:e240100. http://doi.org/10.1590/interface.240100

» http://doi.org/10.1590/interface.240100 -

2 Cunha MLS, Casanova AO, Cruz MMD, Suárez-Mutis MC, Marchon-Silva V, Souza MS et al. Planejamento e gestão do processo de trabalho em saúde: avanços e limites no Subsistema de Atenção à Saúde Indígena do SUS. Saude Soc. 2023;32(3):e220127. http://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-12902023220127pt

» http://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-12902023220127pt -

3 Abrunhosa MA, Machado FRS, Pontes ALM. Da participação ao controle social: reflexões a partir das conferências de saúde indígena. Saude Soc. 2020;29(3):e200584. http://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-12902020200584

» http://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-12902020200584 -

4 Pene BJ, Aspinall C, Deo SS, Wilson D, Parr JM. A bi-cultural multidisciplinary approach to achieving excellence in care for indigenous māori: report from the Wānanga, Auckland. J Adv Nurs. 2024;81(4):2148-58. http://doi.org/10.1111/jan.16622 PMid:39670566.

» http://doi.org/10.1111/jan.16622 -

5 Castro NJC, Simonian LTL. Perceptions and actions of the multi-professional health team on traditional indigenous medicine. 2024;32(1):e77903. http://doi.org/10.12957/reuerj.2024.77903

» http://doi.org/10.12957/reuerj.2024.77903 -

6 Macedo V. O cuidado e suas redes doença e diferença em instituições de saúde indígena em São Paulo. Rev Bras Cienc Soc. 2021;36(106):e3610602. http://doi.org/10.1590/3610602/2021

» http://doi.org/10.1590/3610602/2021 -

7 Monteiro MAC, Siqueira LEA, Frota NM, Barros LM, Holanda VMS. Nursing care for the health of indigenous populations: scoping review. Cogitare Enferm. 2023;28:e91074. http://doi.org/10.1590/ce.v28i0.88372

» http://doi.org/10.1590/ce.v28i0.88372 -

8 Vieira MA, Lima CDA, Martins ACP, Domenico EBLD. Diretrizes curriculares nacionais do curso de graduação em enfermagem: implicações e desafios. Rev Pesqui. 2020;12:1099-104. http://doi.org/10.9789/2175-5361.rpcfo.v12.8001

» http://doi.org/10.9789/2175-5361.rpcfo.v12.8001 -

9 Martins JCL, Martins CL, Oliveira LSS. Attitudes, knowledge and skills of nurses in the Xingu Indigenous Park. Rev Bras Enferm. 2020;73(6):e20190632. http://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0632 PMid:32901747.

» http://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0632 -

10 Hall K, Vervoort S, Fabbro L, Minniss FR, Saunders V, Martin K et al. Evolving beyond antiracism: reflections on the experience of developing a cultural safety curriculum in a tertiary education setting. Nurs Inq. 2023;30(1):e12524. http://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12524 PMid:36083828.

» http://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12524 -

11 Curtis E, Loring B, Jones R, Tipene-Leach D, Walker C, Paine SJ et al. Refining the definitions of cultural safety, cultural competency and Indigenous health: lessons from Aotearoa New Zealand. Int J Equity Health. 2025;24(1):130. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-025-02478-3 PMid:40346663.

» http://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-025-02478-3 - 12 Horta WA. A metodologia do processo de enfermagem. Rev Bras Enferm [Internet]. 1974 [citado 2024 jan 25];8(1):7-15. Disponível em: scielo.br/j/reeusp/a/z3PMpv3bMNst7jCJH77WKLB/?format=pdf⟨=pt

-

13 Moura JWS, Nogueira DR, Rosa FFP, Silva TL, Santos EKA, Schoeller SD. Marcos de visibilidade da enfermagem na era contemporânea: uma reflexão à luz de Wanda Horta. Rev Enferm Atual In Derme. 2022;96(39):e-021273. http://doi.org/10.31011/reaid-2022-v.96-n.39-art.1450

» http://doi.org/10.31011/reaid-2022-v.96-n.39-art.1450 -

14 Ahmadpour B, Turrini RNT, Camargo-Plazas P. Resolutividade no Subsistema de Atenção à Saúde Indígena (SASI-SUS): análise em um serviço de referência no Amazonas, Brasil. Cien Saude Colet. 2023;28(6):1757-66. http://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232023286.13672022

» http://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232023286.13672022 -

15 Barbo G, Alam S. Indigenous people’s experiences of primary health care in Canada: a qualitative systematic review. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2024;44(4):131-51. http://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.44.4.01 PMid:38597804.

» http://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.44.4.01 -

16 Hardy BJ, Filipenko S, Smylie D, Ziegler C, Smylie J. Systematic review of Indigenous cultural safety training interventions for healthcare professionals in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. BMJ Open. 2023;13(10):e073320. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-073320 PMid:37793931.

» http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-073320 -

17 Jull J, Fairman K, Oliver S, Hesmer B, Pullattayil AK. Interventions for Indigenous peoples making health decisions: a systematic review. Arch Public Health. 2023;81(1):174. http://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-023-01177-1 PMid:37759336.

» http://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-023-01177-1 -

18 Rocha ESC, Toledo NDN, Pina RMP, Fausto MCR, D’Viana AL, Lacerda RA. Atributos da Atenção Primária à Saúde no contexto da saúde indígena. Rev Bras Enferm. 2020;73(5):e20190641. http://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0641 PMid:32667395.

» http://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0641 -

19 Souza VRDS, Marziale MHP, Silva GTR, Nascimento PL. Tradução e validação para a língua portuguesa e avaliação do guia COREQ. Acta Paul Enferm. 2021;34:eAPE02631. http://doi.org/10.37689/acta-ape/2021AO02631

» http://doi.org/10.37689/acta-ape/2021AO02631 -

20 Valle PRD, Ferreira JL. Análise de conteúdo na perspectiva de Bardin: contribuições e limitações para a pesquisa qualitativa em educação. Educ Rev. 2025;41:e49377. http://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469849377-t

» http://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469849377-t -

21 Ramsden I. Kawa Whakaruruhau: Cultural safety in nursing education in Aotearoa. Nurs Prax N Z. 1990;5(3):4-10. http://doi.org/10.36951/NgPxNZ.1993.009 PMid:8298296.

» http://doi.org/10.36951/NgPxNZ.1993.009 -

22 Hunter K, Roberts J, Foster M, Jones S. Dr Irihapeti Ramsden’s powerful petition for cultural safety. Nurs Prax Aotearoa N. Z. 2021;37(1):25-8. http://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.007

» http://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.007 -

23 Baniwa G. Educação e povos indígenas no limiar do século XXI: debates e práticas interculturais. Antr Soc [Internet]. 2023 [citado 2024 jan 25];1(1):7-21. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufpe.br/revistas/index.php/antropologiaesociedade/article/view/257830/43643

» https://periodicos.ufpe.br/revistas/index.php/antropologiaesociedade/article/view/257830/43643 -

24 Fernandes RF. Povos indígenas e antropologia: novos paradigmas e demandas políticas. Espaço Ameríndio. 2015;9(1):322-54. http://doi.org/10.22456/1982-6524.53317

» http://doi.org/10.22456/1982-6524.53317 -

25 Ishaque S, Ela O, Rissel C, Canuto K, Hall K, Bidargaddi N et al. Cultural adaptation of an aboriginal and torres strait islanders maternal and child mhealth intervention: protocol for a co-design and adaptation research study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2025;14:e53748. http://doi.org/10.2196/53748 PMid:39793001.

» http://doi.org/10.2196/53748 -

26 Melgueiro-Baniwa EM. Ensino das Línguas Indígenas na Universidade de Brasília: caminhos, desafios, avanços e perspectivas. Sens Public. 2022;1-17. http://doi.org/10.7202/1098425ar

» http://doi.org/10.7202/1098425ar -

27 Bearskin BML, Seymour MLC, Melnyk R, D’Souza M, Sturm J, Mooney T et al. Truth to action: lived experiences of indigenous healthcare professionals redressing indigenous-specific racism. Can J Nurs Res. 2025;57(1):94-111. http://doi.org/10.1177/08445621241282784 PMid:39363826.

» http://doi.org/10.1177/08445621241282784 -

28 Papalini V. Problemas do pluralismo médico: contribuições para uma perspectiva multiepistêmica no Sul global. Soc Cult. 2024;27:e78315. http://doi.org/10.5216/sec.v27.78315

» http://doi.org/10.5216/sec.v27.78315 -

29 Fournier C, Garneau ABL, Pepin J. Understanding the expanded nursing role in indigenous communities: a qualitative study. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(8):2489-98. http://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13349 PMid:33908119.

» http://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13349 - 30 Sousa JMS, Rapozo PHC. Bem viver para os Munduruku. ContraCorrente. 2024;21:300-20. http://doi.org/10.59666/cc-ppgich.v0i21.3609.

-

31 Hinds A, Aguilar SB, Duarte Y, Ospina D, Vargas GJH, Mignone J. Health care utilization and perceived quality of care in a Colombian Indigenous Health Organization. Eval Health Prof. 2024;48(2):230-7. http://doi.org/10.1177/01632787241288225 PMid:39365595.

» http://doi.org/10.1177/01632787241288225 -

32 Santos AFL, Oliveira GDNS, Lima UTS. Experiências de saúde indígena com a etnia Xukuru Kariri. Rev JRG Est Acad. 2023;6(13):862-74. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8050641

» http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8050641 -

33 Lima CAB, Moura IR, Souza AES. Elaboração de um guia para acolhimento de usuários nas Casas de Apoio à Saúde Indígena. Cuad Educ Desarro. 2024;16(6):e4509. http://doi.org/10.55905/cuadv16n6-100

» http://doi.org/10.55905/cuadv16n6-100 -

34 Rojas JG, Herrero R. Changing Home: experiences of the Indigenous when Re-ceiving Care in Hospital. Invest Educ Enferm. 2020;38(3):e08. http://doi.org/10.17533/udea.iee.v38n3e08 PMid:33306898.

» http://doi.org/10.17533/udea.iee.v38n3e08 -

35 Casagranda F, Luz VG, Martins CP, Dias-Scopel RP, Fernandes R, Fonseca W. A saúde indígena na atenção especializada: perspectiva dos profissionais de saúde em um hospital de referência no Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil. Cad Saude Publica. 2024;40(6):e00094622. http://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311xpt094622 PMid:39082566.

» http://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311xpt094622 -

36 Barreto JPL. Bahserikowi – Centro de Medicina Indígena da Amazônia: concepções e práticas de saúde indígena. Rev Antropol. [Internet]. 2017 [citado 2024 jan 25];9(2):594-612. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufpa.br/index.php/amazonica/article/view/5665/4679

» https://periodicos.ufpa.br/index.php/amazonica/article/view/5665/4679 -

37 Komene E, Davis J, Davis R, O’Dwyer R, Te Pou K, Dick C et al. Māori nurse practitioners: the intersection of patient safety and culturally safe care from an Indigenous lens. J Adv Nurs. No prelo 2024. http://doi.org/10.1111/jan.16334 PMid:39007636.

» http://doi.org/10.1111/jan.16334

Edited by

-

ASSOCIATED EDITOR

Gerson Luiz Marinho https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2430-3896

-

SCIENTIFIC EDITOR

Marcelle Miranda da Silva https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4872-7252

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

08 Sept 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

03 Apr 2025 -

Accepted

07 July 2025

Nursing process in an indigenous population healthcare service

Nursing process in an indigenous population healthcare service

Source: prepared by the authors (Canva Pro. Available on

Source: prepared by the authors (Canva Pro. Available on  Source: prepared by the authors (Canva Pro. Available on

Source: prepared by the authors (Canva Pro. Available on