Abstract

This article seeks to build the history of Deaf Education in Brazil, based on the analysis of teaching approaches: Oralism, Total Communication and Bilingualism, based on discussions of pedagogical practices implemented in schools at different historical moments. The motto of this discussion and analysis are the pedagogical guidelines, and in particular the activities developed in the classroom. When thinking about Deaf Education and the implication of the approaches in the different periods one cannot construct a linear and sequential continuum, but there must be an existence diluted and diffused in different degrees in different historical periods. The didactic division of the three great approaches cannot compromise the understanding of this object, making it simplistic. The impacts of the different approaches for Deaf Education can be verified in the students’ schooling process. The fact that practices characterized by an approach that would theoretically belong to the nineteenth century are present in an effective way in the classroom and in pedagogical practices, in the teacher-student relationship and in our contemporary social representations of the deaf student in the school environment.

Pedagogical practices; Deaf education; School activities; Teaching approaches

Resumo

Este artigo teórico busca construir o histórico da educação de surdos no Brasil. A partir da análise das abordagens de ensino: Oralismo, Comunicação Total e Bilinguismo, discutem-se práticas pedagógicas implementadas nas escolas nos diferentes momentos históricos. O mote desta discussão e análise são as orientações pedagógicas e, em específico, as atividades desenvolvidas em sala de aula. Ao pensarmos a educação de surdos e a implicação das abordagens nos diferentes períodos, não se pode construir um continuum linear e sequencial, mas uma existência diluída e difundida em graus diferenciados nos diversos períodos históricos. A divisão didática das três grandes abordagens não pode comprometer a compreensão deste objeto, tornando-a simplista. Os impactos para a educação de surdos das diferentes abordagens podem ser constatados no processo de escolarização desses estudantes. Destaque para o fato de que práticas caracterizadas por uma abordagem que, teoricamente, estaria no século XIX, estão presentes de forma efetiva em sala de aula e nas práticas pedagógicas, na relação professor–aluno e na representação social que ainda se tem do estudante surdo no espaço escolar.

Práticas pedagógicas; Educação de surdos; Atividades escolares; Abordagens de Ensino

Introduction

Based on the historical construction done by a number of authors such as Brito (1993) BRITO , Lucinda Ferreira . Integração social e educação de surdos . Rio de Janeiro : Babel , 1993 . ; Goldfeld (1997) GOLDFELD , Márcia . A criança surda: linguagem, cognição: uma perspectiva sócio interacionista . São Paulo : Plexus , 1997 . ; Moura (1999); Skliar (1999) SKLIAR , Carlos ( Org .) . Atualidade da educação bilíngue para surdos . v. 1-2 . Porto Alegre : Mediação , 1999 . ; Sá (2002) SÁ , Nídia Regina Limeira de . Cultura, poder e educação de surdos . Manaus : Universidade Federal do Amazonas , 2002 . , whose groundwork were several different educational approaches for the deaf, we will be using pedagogical guidelines and activities that took place in the classroom, and will be discussing the temporality and the presence of such approaches in our pedagogical practices of recent years.

These approaches have left their imprint in the schooling process of deaf students, as demonstrated by Sá (1999) SÁ , Nídia Regina Limeira de . Educação de surdos: a caminho do bilinguismo . Niterói : EdUFF , 1999 . , Góes (2002), Fernandes (2003) FERNANDES , Eulália . Linguagem e surdez . Porto Alegre : Artmed , 2003 . , Pereira & Karnopp (2004), Gesueli (2004) GESUELI , Zilda Maria . A escrita como fenômeno visual nas práticas discursivas de alunos surdos . In: LODI , Ana Claudia Baliero et al . ( Org .) . Leitura e escrita no contexto da diversidade . Porto Alegre : Mediação , 2004 . p. 39 - 48 . , Guarinello (2007) GUARINELLO , Ana Cristina . O papel do outro na escrita de sujeitos surdos . São Paulo : Plexus , 2007 . , Dorziat (2009) DORZIAT , Ana . O outro da educação: pensando a surdez com base nos temas Identidade/Diferença, Currículo e Inclusão . Petrópolis : Vozes , 2009 . , Lacerda & Santos (2013) LACERDA , Cristina Broglia Feitosa ; SANTOS , Lara Ferreira . Tenho um aluno surdo, e agora? Introdução a Libras e educação de surdos . São Paulo : EdUFSCar , 2013 . , when discussing deaf students’ learning process. This imprint can still be identified nowadays in the activities which are being conducted in the school environment, through the results that are presented in this article.

This theoretical and documentary article results from bibliographical and field research, through the gathering of pedagogical guidelines and school activities. Based on these guidelines and activities, we have produced a scientific text which brings to the foreground the pedagogical practices that are being conducted in Deaf Education, through approaches such as Oralism, Total Communication and Bilinguism.

Development

Oralism is an educational approach that prioritizes speech. In this approach, the whole process aims at rehabilitating the deaf, i.e., bringing them closer to the “hearing world”. It has been necessary to enable them to speak as if they could hear, even if they did so without the same fluency or intonation. From this stage onwards, they would be able to learn. This approach, when established as a path for the schooling of the deaf, makes the individual responsible for his/her accomplishment or failure. At the beginning, the deaf were not allowed to communicate through gestures ; nowadays they are not allowed to use the sign language.

Concerning the adoption of Oralism and its shift towards Total Communication, Brito (1993) BRITO , Lucinda Ferreira . Integração social e educação de surdos . Rio de Janeiro : Babel , 1993 . argues that the approaches in the Deaf Education be summed up in ‘ oralisms and bilinguisms ’, and his viewpoint is supported by Fernandes & Moreira (2014) FERNANDES , Sueli ; MOREIRA , Laura Ceretta . Políticas de educação bilíngue para surdos: o contexto brasileiro . Educar em Revista , Curitiba , n. spe-2 , p. 51 - 69 , 2014 . Disponível em: < http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.37014> . Acesso em: 2 abr. 2018 .

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.3701...

and Lopes & Freitas (2016) LOPES , Sonia de Castro ; FREITAS , Geise de Moura . A construção do projeto bilíngue para surdos no Instituto Nacional de Educação de Surdos na década de 1990 . Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos , Brasília, DF , v. 97 , n. 246 , p. 372 - 386 , ago . 2016 . Disponível: < http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S2176-6681/374713703> . Acesso em 10 abr. 2018 .

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S2176-6681/374...

, authors who demonstrate, based on empirical data, that Oralism was applied in Deaf Education at INES [Instituto Nacional de Surdos, National Institute for the Deaf] until the mid-1990s.

Fernandes & Moreira put forward arguments presented by Skliar (1998), in which he analyzes the historical background against which sign languages were prohibited, due to the unification of the Italian State, a process in which Italian language was a unifying element. In that context, the banning of sign language from schools contributed to diminishing a factor of linguistic deviation, forcing the deaf children to learn how to speak the lingua franca , in spite of their organic inability of doing so (SKLIAR, 1998, p. 54).

In that scenario, the sign language becomes virtually invisible during the nineteenth century, which may be regarded as a setback for the linguistic development of this community, with all the possible consequences.

Lopes & Freitas, in their turn, report on what took place in the decades of 1980 and 1990, at the INES, in its ‘Escola de Aplicação’, whose students were exclusively deaf people. The project undertook in the 1980s was the same as the one carried out by the principal of the school, Ana Rímoli de Faria Dória, between 1951 and 1961, but uniquely from an oralist perspective. Using this approach, Dória produced materials under the name of Compendium of Education of the Deaf-Mute Child. This text was used for decades as pedagogical material for teaching these students. Lopes and Freitas indicate that, in 1989, the efficiency of oral methodologies started being questioned.

These elements corroborate the fact that Total Communication is regarded as part of Oralism. In Total Communication, gestures are regarded as valid for establishing communication, they are regarded as accessories to learning and a learning tool for the oralization of deaf students. Therefore, these authors consider that Total Communication consists of an Oralism with the inclusion of gestures or signs without the same importance of an ordinary language.

These students’ skills were put to the test during this period of nearly a hundred years during which this approach was in effect in Brazil. The student’s hearing handicap was ignored and disdained. This disdain becomes apparent when we look at the state of submission these students live in. The first important struggle of the militant among the deaf was to empower and recognize their abilities and conditions for living in society without difficulties, provided that linguistic and pedagogical barriers could be overtaken by a process of teacher training which recognizes the differences between people. The hearing handicap is also ignored in the sense that one does take into account the individual’s biological handicap, i.e., his inability to hear naturally.

Around 1900 and also at the beginning of the 1990s, people’s hearing handicap was regarded as temporary. It was assumed that overcoming this handicap depended exclusively on personal struggle and the dedication demonstrated from students’ families. People were supposed to be able to live together in equal conditions, in a way that differences were valued.

Parents would then be oriented to seek help from speech therapists and never use the so-called “gestures” or “mimicking” when communicating with their children. By doing so, they tried to make sure that the deaf did not display their condition in public.

The oralist approach in Deaf Education aims at enabling the deaf to use the language of the hearing community in its oral modality as the only linguistic possibility. In this approach, the use of voice and lip reading is made possible either in social exchanges or in the whole educational process. Language in its oral modality is, therefore, a means and an end in the educational process and within social integration. ( SÁ, 1999 SÁ , Nídia Regina Limeira de . Educação de surdos: a caminho do bilinguismo . Niterói : EdUFF , 1999 . , p. 69, our emphasis).

When regarded as a means and an end, oral language prevents students from participating effectively. The common belief is that a hearing aid (auditory prosthesis) and long training in speech are able to promote the integration of the deaf in the educational process, obviously with limitations, since these are handicapped people.

The use of voice and the practice of lip reading are not as easy and straightforward as they seem; it takes great effort and discipline both from students and from parents. Therapy sessions during the week, including home sessions, are necessary.

According to Fernandes (2011) FERNANDES , Sueli . Educação de surdos . 2 . ed. Curitiba : Ibpex , 2011 . , ‘Oralism was predominant worldwide as an educational philosophy from the decade of 1880 until the mid-1960s’; in Brazil, Total Communication, which emerges right after Oralism, starts being adopted in schools around the 1990s.

Oralism was in effect for a long time in educational institutions, and during this period a number of pedagogues, phonoaudiologists and otorhynolaryngologists got their degrees, all of them believing in the incapacity of the hearing impaired , and striving to promote the “normalization” of such people.

These special pedagogical methods were based on the training of students’ phonoarticulatory system, and the practice of pronouncing phonemes 3 3 - In the course “Education with a major in Audiocommunication for the Hearing Impaired, we would learn how to ‘put’ phonemes in our students, for example in activities such as putting up something on their lips so that they might be able to distinguish the articulation of the phoneme /m/, and by doing so, be able to learn it. . Students would spend their time in school training exercises on vowels. Some of these exercises had no context, they were nothing but drilling.

For the hearing impaired to achieve good results, special pedagogical methods will be needed, which may foster appropriate stimulation, making it possible for his/her language acquisition and oral development. ( COUTO, 1986 COUTO , Álpia . Posso falar: orientação para o professor de deficientes da audição . 2 ed. Rio de Janeiro : EDC , 1986 . , p. 11, our emphasis).

A period of almost a hundred years promoting children’s rehabilitation has led to consequences. After all, many deaf people were failing because of their physical handicaps (not because of deficient functioning of their auditory system). However, these beliefs became an issue that was focused on the individual and not on the method. Still, since the 1960 some studies have contributed to changes that have occurred in Deaf Education.

Maria Aparecida Leite Soares, in a book published in 1999, presents studies carried out in the United States with guidelines for teachers of hearing impaired children. Some excerpts of this book are relevant to our discussion:

[...] it is recommended [that the teacher have] practical knowledge on the physics of sounds and that s/he master the acoustic equipment s/he will be dealing with. Classrooms have to be isolated from external and internal noise, the volume of the equipment has to be adjusted to the individual headphones, according to each student’s hearing capacity. Stimulation should start with the presentation of powerful sounds coming from musical instruments such as drums, cymbals (string instruments), gongs, bells. ( SOARES, 1999 SOARES , Maria Aparecida Leite . A educação do surdo no Brasil . Campinas : Autores Associados ; Bragança Paulista : Edusf , 1999 . , p. 72).

Teachers were instructed to recommend phonoaudiology therapy sessions to their students, aiming at the development of speech as well as the use of a hearing aid; however, in spite of all these individual and family efforts, a significant number of students still failed.

A hand typed handbook (1983) was used as guidelines for the work developed by many public school teachers of São Paulo City in the 1980s. The introduction of the text encouraged teachers in their work, and gave God the credit for choosing the professionals who would contribute in the work with the hearing impaired , as if their job were a priesthood.

In the school environment, the work of promoting students’ rehabilitation remained the same, and all the activities focused on validating the belief in the ‘normalization’ of the hearing impaired in order to use the same methods applied to the hearing students.

The guidelines of the handbook would show the teachers how to indicate the rhythm and the intensity of these sounds. It was deemed necessary to make the hearing impaired utter the sounds and regulate them, so that they might be able to say the syllables and, next, say the words. Having done so, the hearing impaired would be able to complete the literacy learning cycle in the same way as the hearing students.

This procedure made it difficult for the hearing impaired students. They kept repeating the same grade until they were able to say all the phonemes within the planned syllabus, and then move ahead in their learning process.

By that time, school for the hearing impaired was viewed as a therapeutic place rather than an educational environment. The teachers’ job was not limited to working on their syllabus and discussing concepts; rather, they were supposed to focus on rehabilitating students’ speech. And they did so based on resources which had close resemblance with the ones used with the hearing children. The basic principles of the literacy learning process were also identical.

The training of this teacher included learning about the resources to help students in saying the phonemes, the functioning and handling of Collective and Individual Devices of Sound Amplification.

There still remained the belief on the ‘normalization’ of the individuals, which would turn them into ‘nearly’ hearing people: therefore, the nature of teacher’s work was phonoaudiological, rather than educational.

[...] a series of exercises aiming at training students’ audition, with regard to the presence or absence of sounds as well as the recognition of high-pitched and low-pitched musical notes. Students should answer by raising and lowering their arms. They do so through music, asking the teacher to play the record and interrupt its playing several times. First, this is done in a way that students may observe the teacher and raise their hands when the record is being played, and lower their hands when music stops. Later on, the teacher will repeat the same exercise, but students will then give their back to the record-player, so that they cannot see the teacher’s movements, turning the music on and off. ( SOARES, 1999 SOARES , Maria Aparecida Leite . A educação do surdo no Brasil . Campinas : Autores Associados ; Bragança Paulista : Edusf , 1999 . , p. 73).

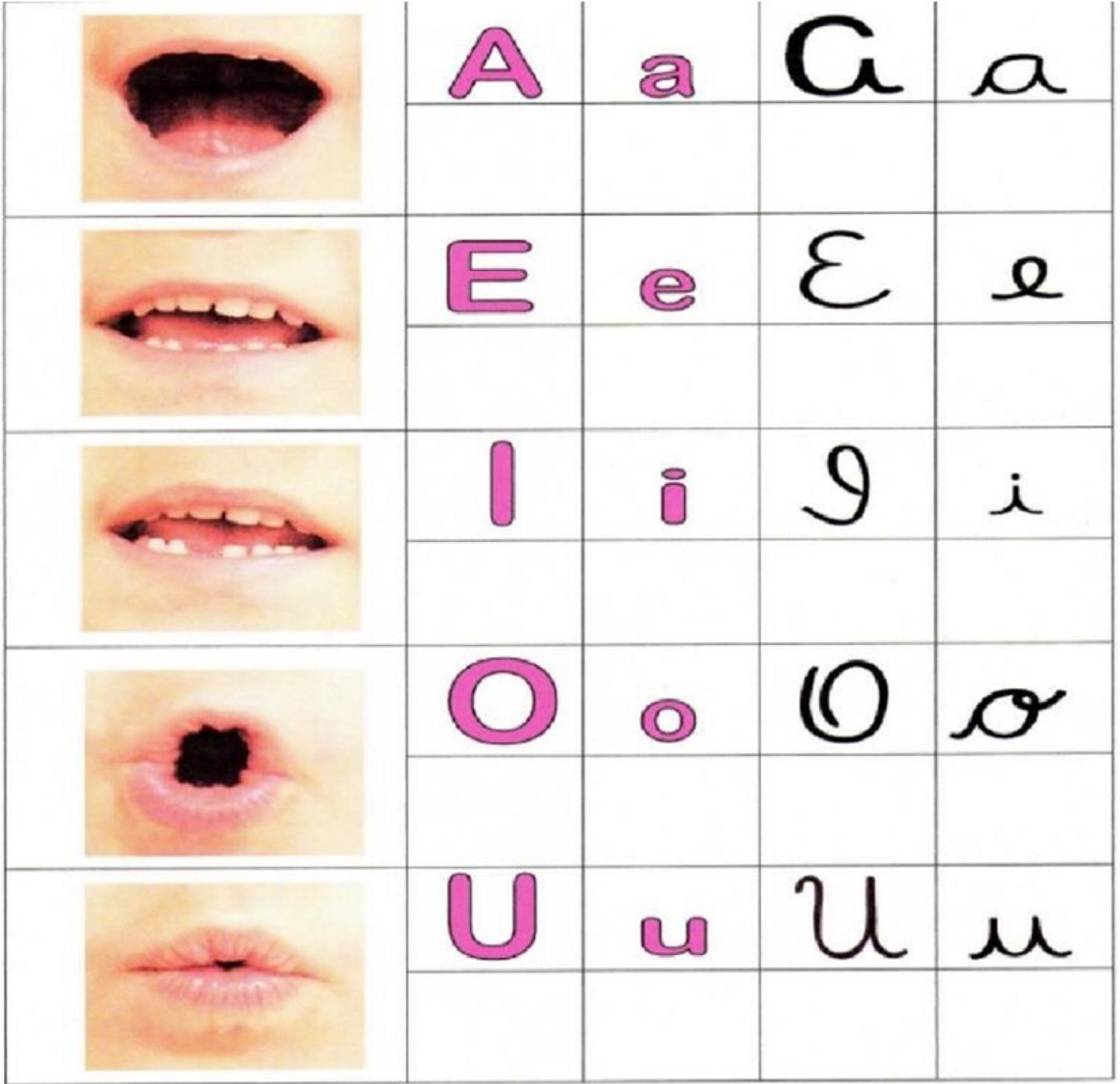

Visual hints were given to students, which imitated the shaping of the mouth in the pronunciation of the phonemes. It was assumed that children might be able to imitate these shapes and, therefore, be encouraged to reproduce these sounds.

This activity was included in the weekly routine of deaf students in school. For each phoneme they learned, they were shown images so that they could observe, assimilate, and repeat them.

In addition to sticking those images on their notebooks and repeating those sounds at school and at home, they should, based on the hints given, write the phoneme that was pronounced; next, write the syllables, and at last, the words.

Since it was believed that, for learning to take place, sounds should be taught before writing, the phonic method was taken into schools and the special classrooms for the deaf. This procedure was based on the ‘first, the sound; next, its equivalent graphic image’ principle.

In some activities, students were asked to watch their teachers’ mouths, then try to reproduce the sounds and associate such sounds with letters, a process in which each one of the pictures represented the articulation of one phoneme.

This is the so-called process of validation and the lip reading training. This method was used by therapists out of school (for some of the children), but also in the school, by the pedagogue or the teacher who was responsible for the group.

The guidelines for public school teachers who worked for the Municipality of São Paulo City, summarized in a handbook entitled ‘Program of Systematized Structuring of Language”, presented the way in which the activities should be conducted. The aim was to ‘make the hearing impaired acquire the spirit of the language’. ( BRAGA, 1983 BRAGA , Mário Joel da Silva . Programa de estruturação sistematizada da linguagem para deficientes auditivos . São Paulo : Secretaria de Educação Municipal , 1983 . Mimeo . , p. 2).

This handbook was a kind of manual. As soon as they started working for the Municipality of São Paulo, teachers would be given a copy of it, which was used as a sort of primer. Activities were planned, starting with the words associated to the selected phoneme. This procedure showed close resemblance to the one applied in primers, with groups of syllables.

Below is an example of words presented in the material: pá [shovel], pé [foot], pó [dust], pau [stick], pia [sink], pua [brace] 5 5 - [Also: brace and bit]: A drilling tool with a crank handle and a socket to hold a bit. (From: The New Oxford Dictionary of English). , pão [bread], pião [spinning top], pipa [kite], papai [daddy], papel [paper]. These words are not related to one another unless for their initial letter, the phoneme. One of them, “pua” [brace] is not often used in ordinary daily conversations, it is not in the texts or in its dialogs.

A “motivated presentation” was a requirement for the undertaking of this activity. The teacher should help students with the placement of phonemes and also explain to them, based on images, the meaning of the words associated to such images.

In the chapter ‘Theoretical Justification’, the handbook states:

At the beginning, the teacher should not dwell on students’ poor articulation, all s/he needs to do is to have the student repeat the mispronounced word, but without making corrections or insisting on it. In case s/he realizes that, after a few repetitions a letter is omitted or mispronounced, then his/her intervention will be needed. Articulation without special exercises is generally ok, apart from one letter or another, which may need to be given a particular focus ( BRAGA, 1983 BRAGA , Mário Joel da Silva . Programa de estruturação sistematizada da linguagem para deficientes auditivos . São Paulo : Secretaria de Educação Municipal , 1983 . Mimeo . , p. 2).

It was then necessary to focus particularly on the phoneme ‘P’, through several drilling exercises, which involve the pronunciation and the perception of this sound. Next, the activity conducted with the highlighted words focused on the phoneme (context), adding some other elements (phonemes) with images that identified the words selected.

During the period when Oralism was in effect in schools, i.e., from 1952 – when EMEBS Helen Keller [Municipal School of Bilingual Education for the Deaf, in São Paulo-SP] was founded – until the 1990s, teachers would use a (usually square and wooden) box filled with images, containing several images taken from magazines, books and leaflets. The files usually had the same size and were classified by letters in the alphabetical order, an interesting strategy for expanding vocabulary. Nonetheless, students were required to show something that went beyond their own physical and biological limitations, something they did not have: the hearing ability.

Teaching strategies are presented in four steps, and suggest a kind of graduation: Concrete, Semi-Concrete, Semi-Abstract and Abstract. They started from the image and the presentation of the word (orally or through an image), contributing to helping with students’ memorized writing, and vocabularization.

In the exercises are given examples of activities in which the process of literacy teaching starts from a fragment until it covers the whole. At this stage, it also includes the hearing students, through the traditional teaching method: words, syllables, words, sentences, clauses and texts, until the student is able to master the words selected at the beginning of the learning process. S/he then either writes the word recently memorized or uses such a word to complete blanks in sentences or texts.

It is noteworthy that the Oralist approach also aimed at the learning and practice of lip reading. This exercise was performed not only inside schools and clinics, but also in the households. Family was an important aspect of this process, given their huge responsibility in a process that might result in their impaired children’s achievement or failure.

Sá (1999) SÁ , Nídia Regina Limeira de . Educação de surdos: a caminho do bilinguismo . Niterói : EdUFF , 1999 . presents a historical retrospective on Deaf Education and, in a chapter on Oralism, includes excerpts of interviews made with teachers, parents and some deaf students, called here hearing impaired. In order to illustrate the teachers’ behavior with regard to the activities we presented earlier, we will reproduce below a curious excerpt selected by the researcher.

‘In classroom, I could do whatever I wanted, it’s not like today, when the child goes straight to the communication cabin. Not us. We used to have the speech section in the classroom, the part dedicated to the auditory training; the whole work was done in classroom. At that time, the phonoaudiologist was the teacher herself, who was appointed to go the cabin.

Later on, I was lucky enough to work in a section called Vibrassom, which used a method in the Verbotonal style (but was not exactly this one). This was one of my best experiences. We had headphones in the classrooms. The student would be taken to the communication cabin or the rhythm cabin and worked on the same phonemes that we were working on in the classroom’. (T – Teacher of the Deaf Students) (p. 77-78).

This quote shows us how thoughtful teachers were and how concerned they were in enabling their students to develop speech. Their objectives and learning goals could be measured through these practices. The importance of a teacher with a clinical, rehabilitating and pedagogical role was stressed. Everything was carefully planned, and put in practice. The classrooms had spaces dedicated to the work of sound stimulation, which was a path towards learning.

When we look into the practices involved in the Oralist approach, it is necessary to bear in mind the historical context in which it takes place, as well as the pedagogical proposals at that time. When doing so, we should not judge them based on our current value judgment. At that time, those were the most developed methods, the ones that led to the best possible results, concerning students’ rehabilitation.

The building and the organization of the educational facilities used to reflect people’s mindset at that time with regard to hearing impaired people, a mindset in which their handicap was emphasized.

After over a hundred years being practiced in the classrooms, Oralism has not led many deaf students to successful results. Although it was said that, through their efforts, the hearing impaired would attain success, this did not happen.

Moura (2000) MOURA , Maria Cecília . O surdo: caminhos para uma nova identidade . Rio de Janeiro : Revinter , 2000 . presents the witness of a Brazilian deaf guy talking about his family, friends and school:

[...] I used to write the letters, the alphabet. I would learn how to write, so and so [...] My teacher would always teach us short sentences, instead of long ones [...] for instance: ‘The ball is beautiful’. She never taught us long sentences. I learned short sentences, they were always the same, I’d never move ahead. I never heard anything different, I’ve never learned . (p. 113, our emphasis).

When s/he says ‘I’ve never learned’, the student expresses pain and anguish for having spent many years in school without a glimpse of what learning is.

Many students could not speak well, which made them unsuccessful in their school and social life. Hearing impaired children had their previously assigned places; one did not expect much from them beyond the reproduction of a few sentences regarded as important, but that also created problems.

In the late 1980s, a new educational approach gets established in Brazil, an approach that tries to compensate for the failures in the educational process of the hearing impaired.

Total Communication emerges in the educational scenario as an alternative to Oralism. The basics of this new approach are to allow the students to use signs – which still have no characteristics of a language – as well as any resource which may allow students to communicate with teachers.

In the history of Total Communication, no particular event represents a landmark, as it is the case of the Congress of Milan, in 1880, for Oralism. It develops out of a feeling of dissatisfaction with the results of Oralist education, a feeling that is expressed worldwide. After being tried with several generations of deaf people, this approach did not lead to satisfactory results. ( SÁ, 1999 SÁ , Nídia Regina Limeira de . Educação de surdos: a caminho do bilinguismo . Niterói : EdUFF , 1999 . , p. 106).

This is regarded as progress, given the fact that, under Oralism, the use of signs, mimicking or gestures as a learning resource was absolutely forbidden. However, it is important to point out that, for Total Communication, the emphasis is placed on rehabilitation; thus, it is a paradigm adopted with a medical bias.

The basic premise was the use of all possible ways of communication with the deaf child, and no particular method or system should be omitted or emphasized. In order to do so, natural gestures (Ameslan, American Sign Language), the digital alphabet and facial expressions should all be used. All of these communication ways should be used along with the speech that would be heard through an individual device for sound amplification. The basic idea was to make use of anything that could convey vocabulary, language and concepts between the speaker and the deaf child. The important concept was to make room for two-way, easygoing and fluid communication between the deaf child and people in her environment. (NORTHERN; DOWNS, 1975 6 6 - NORTHERN, J. & DOWNS, M. - Hearing in Children . Maryland: The Williams and Wilkins Company, 1975. apud MOURA, 2000 MOURA , Maria Cecília . O surdo: caminhos para uma nova identidade . Rio de Janeiro : Revinter , 2000 . , p. 57-58).

In the USA and in Brazil the main purpose of such an approach was communication and, resulting from this process, a movement is established in which the “signs borrowed” from Sign Language are used, with a correspondence established with words: Portuguese, in the Brazilian case. The hearing impaired would then be using all his potential in order to learn signs, understand the activities and expand their vocabulary. This practice was called ‘Bimodalism’ [also called “português sinalizado” in Brazil, or “Portuguese with signs”], since it involves the use of two kinds of different languages – the oral and the visual, in this particular case –, leading us to believe in the correspondence between the sign and the word, which fails to characterize Sign Language as a language, considering it exclusively as a representation of the predominant language.

Although better results were expected in the acceptance of gestures and signs, this approach still did not regard the deaf student as responsible for his learning; he was still considered a hearing impaired person who, according to Oralism, needed rehabilitation.

Classroom activities were still mistaken for clinical and therapeutic practices. Students were expected to be able to ‘orally’ pronounce syllables, words and sentences, as it happened under Oralism.

Oral language still played an important role, and the instruction given to parents was that their impaired children should learn lip reading. By doing so, they would be able to follow the syllabus of the courses in school. In a nutshell, what really changed was the acceptance of the signs, but the name, the emphasis and the conceptions of subject and language remain the same as they were in under Oralism.

In 1998, a publication designed by a program called ‘Comunicar’, created by a clinic in the Minas Gerais state, with the support of Ministry of Education and Sports, through the Secretariat of Special Education, was handed out to some schools where hearing impaired students went to, schools that were part of the São Paulo State Education Network. This consisted of a number of handbooks and videotapes in which samples of activities and exercises for students’ ‘rehabilitation’ were presented.

Although we said earlier in this article that in the 1990s a new approach was being adopted, this handbook published in 1998 shows us to what extent Oralism was still predominant in schools and also how the Ministry of Education itself gave support to these educational materials.

The complete kit contains five books: Book 1 – Guidelines for the family and the school; Book 2 – Psychomotor and psychopedagogical exercises prior to literacy teaching; Book 3 – A small visual dictionary; Book 4 – Sign Language Acquisition and Development; and Book 5 – Oral Language Acquisition.

This material is predominantly prescriptive, suggesting the work must be done through all possible ways of communication and using all possible resources. The criticism to such a suggestion lies in the fact that Sign Language cannot be regarded as a simple resource or tool. This handbook takes Sign Language out of the discursive context – such a view does not favor the comprehension of a language in its totality. Besides, at that time Libras (‘Língua Brasileira de Sinais’, or Brazilian Sign Language) was still not considered a language.

Curiously enough, although Book 5 was meant to discuss and provide the reader with information about the oral language acquisition, its first topic consists of guidelines to families about the speech therapy.

This material makes it clear that the learning process for the hearing impaired is an ongoing and repetitive process. Everything that takes place in school also takes place in the phonoaudiology clinic, and also in the households. In other words, school becomes an extension of the clinic. The first item of the topic states that the child should practice this ‘conditioning’ at least 30 minutes a day, including weekends and holidays, a practice that takes huge effort both from the child and his/her family.

In spite of such recommendation, many of these students did not demonstrate such a dedication nor had the necessary conditions or skills to be able to develop lip reading skills, and be efficient oralized. As a result, these hearing impaired people became even ‘more impaired’ than their peers. For them, failure was an internalized status, and they conformed to what was offered to them by educational institutions – meaningless contents and an extension of the phonoaudiology clinic.

This idea is relevant in the sense it shows us the fact that these different approaches intertwine, so to speak. The activities performed in clinics or in classrooms did not change at the same pace as theories were presented. Therefore, in 1998, daily practices were still very much based on what had been done prior to this new approach.

The Verbotonal method, which was a rehabilitation program, start being adopted in Brazil at the same time as Oralism. And during the period that Total Communication was in effect, i.e., in the 1990s, many students made use of this therapeutic method, which shows us, once again, that these two approaches were not too different from one another in their practices.

At school, the teaching process was based on short sentences with fixed structures so that students might be able to memorize this pattern for the pronunciation of words. The student was encouraged to orally utter the sentences that were structured this way and, based on them, teachers would start working on writing skills.

The exercises worked on images that alluded to actions. These images contained some sentence structures in Portuguese whose pattern students were supposed to imitate. They would start working this way and then would start replacing some of the words in the sentences.

In this activity deaf students were supposed to replace the subject of the clause such as in ‘My cousin jumps, My sister jumps, The girl jumps, Mary jumps’ (based on the image of a girl that might represent different female characters). But this would only effectively happen if the teacher’s instruction was very clear, so that student could understand it. Total Communication does not use Libras as a language – this language came into effect in Brazil only in 2002 –, but it does use the signs of this language as a tool.

During the 1990s the ‘indiscriminate’ use of images aimed at helping students in their learning process became very popular. Students were exposed to several images so that they might be able to see the connection between images (signs), the written word and the spoken word. It was assumed that, by looking at an image, the student would automatically connect it to its written form, based on the sound or on the memory of what he had been exposed to.

However, images are part of a very complex and polysemic realm, which creates difficulties for the teacher’s intentions. An image that a student is exposed to, may or may not, according to his/her experiences, correspond to the concept of what the teacher previously had in mind.

The hearing impaired students ’ participation in social and family activities was not very active. Their comprehension of academic questions, psychical constructions and experiences were hindered by their limited linguistic repertoire. This hindrance, according to Vygotsky (2014) VYGOSTKY , Lev Semyonovich . Obras escogidas II: pensamiento y lenguaje conferencias sobre psicología . Madrid : Machado Grupo de Distribución , 2014 ., is directly associated to one’s process of comprehension of the world, to the social construction of the mind and to cognition.

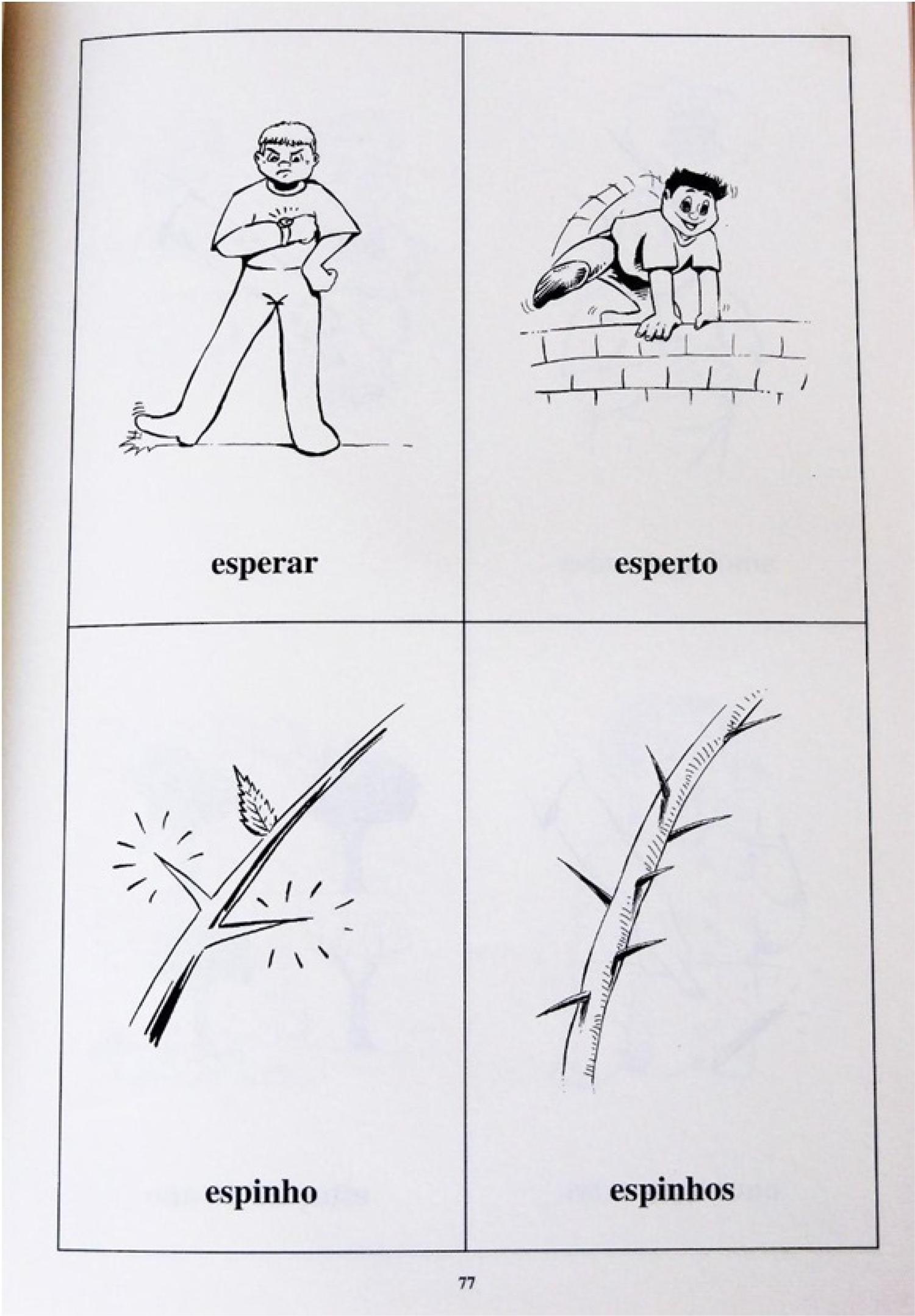

– Page of the book containing vocabulary – ‘esperar’/‘esperto’/‘espinho’/ ‘espinhos’ [wait/clever/thorn/thorns]

The figure above shows us how ambiguous an image can be. It implies the need of an interlocutor whose repertoire enables him/her to conceptualize it and understand what the image refers to.

In the image related to the verb ‘esperar’ [wait] a boy looks at this watch and stamps his foot. This image can be interpreted in different ways, depending on who is looking at it, on his/her linguistic background and life experience. This very image may be associated to feelings of impatience or boredom, but it may also be neutral, just a boy looking at his watch and stamping his foot.

The image with the word ‘esperto’ [clever] shows a boy jumping over a fence, which may be interpreted in different ways, being associated to training, exercises, a literal jump, an escape etc. Rather than a simple correspondence between image and word, one is concerned here with the building of the concepts for the development of higher mental functions. In this image, built-in value judgment is being expressed through the meaning of the concept of ‘esperteza’ [cleverness].

The oddest images, though, are the ones that correspond to ‘espinho’ [thorn] and ‘espinhos’ [thorns] . First of all, here we can see two different images, and the difference between them should lie in the number of thorns (plural or singular). However, the image for ‘espinho’ shows one leaf, and the two stems that seem to represent the part of the plant which may puncture. By doing so, it already implies the plural form, hence eliminating the difference between this image and the one by its side. The image of ‘espinhos’ [thorns] apparently shows a different kind of thorn, not directly related to the image for ‘espinho’ [thorn] , but which might be interpreted some other way.

Within this context, we often find instructions which label, so to speak, the world for the deaf people, as well as names of things written everywhere. In some cases, even Libras signs are used as mnemonic resources.

From a theoretical perspective, Deaf Education was no longer Oralist. Yet, school activities, in effect, still reflected the contents of the old model, and teachers still regarded the deaf person as someone who needed rehabilitation.

Based on these manuals, some teachers prepared their materials using different colors and shapes in order to represent grammar categories in the Portuguese language. In classroom, they used a strategy to enable their students to “see” how sentences are built in Portuguese.

We recommended to teachers that, from the basic literacy cycle onwards, they start using some sort of highlighting of the elements of clauses, so that the child might understand their syntactic function. Just to exemplify it, the subject could be highlighted with a yellow chalk, the verb in white, the predicate in blue, the direct object in green, the indirect object in pink, the adverbial adjunct in purple… In a second stage, we could also conjugate these clauses in the present, past and future tenses. Some teachers have been using these examples by replacing the elements of the clause, in order to enrich the materials. For example, the subject of the clause ‘My cousin jumps’ from the first example that we commented above, could be replaced by another word such as ‘the student’ or ‘the teacher’; alternatively, the verb of this clause could be replaced by ‘goes down’ or ‘walks’. ( CALDEIRA, 1998 CALDEIRA , José Carlos Lassi . Exercícios psicomotores e psicopedagógicos anteriores à alfabetização: Programa Comunicar . Belo Horizonte : Clínica-Escola Fono , 1998 . , Book 5, p. 114).

Therefore, we can say that Total Communication still gave priority to the Portuguese language, blending a few language signs into the background in order to facilitate students’ comprehension. Yet, this was not enough for impaired hearing people to build up their thoughts, since they needed to get as close as possible from the hearing community, if they wanted to have their educational rights granted.

However, this approach still regards the deaf person as a hearing impaired person, and Libras is not yet regarded as a language; it is, in a few cases, a tool. Below is the transcription of two dialogs from the manual ‘Comunicar – Book 5’:

Some of the words used in these dialogues are noteworthy, since they contain prescriptions adopted by the Oralism, although they belong to Total Communication.

The first question in this dialogue is: ‘Are you a deaf or a hearing person?’ The person does not answer that s/he is deaf, but has a moderate-hearing loss. In other words, deafness is still not part of his/her identity, it is based on the thresholds of hearing loss, and the person identifies with it based on the clinical model. S/he also indicates her/his degree of hearing loss, a piece of information that most of the deaf people simply ignore.

The person states that his/her teacher uses Portuguese with signs [‘português sinalizado’], a practice which shows that the Portuguese language is preponderant over Brazilian Sign Language, since it is based on the use of a sign for each word in Portuguese, to such an extent that non-contextualized signs have been ‘created’ to make for this juxtaposition, such as in the words ‘for’, ‘of’, ‘stay’. In addition, people with hearing loss , or, as we call them today, hearing impaired people – or deaf –, have a better comprehension when we use signs that are associated to speech, bimodalism, and juxtaposed languages of different modalities.

The dialogue also brings an approving reference to the use of a hearing aid as well as the speech and lip reading practices, which suggests a closer proximity between deaf people and hearing people, and also indicates a process of normalization and naturalization in the school environment.

The material presents a mistaken conception of the manual alphabet, as though all the learner’s problems could be solved by the time s/he learned it. According to this material, Sign Language should be taught at a slow pace, and Libras should be used only “when they need it”, i.e., as a last resource, and for the hearing impaired who were not successful in their learning process.

The school staff includes two phonoaudiologists, and people with hearing loss need extra tuition classes, since they cannot keep up with the regular syllabus in their classroom.

One may give different names to these approaches, calling them ‘philosophies’ and one may also change the way of working with them, but if one does not review their presumed conceptions about the deaf person and about what is done in his benefit, all professionals will be doing a disservice to the deaf, and maintaining their status as it is. The main question is: to whom and for what is this service being done? Apparently, in spite of the changes that have occurred so far, the aim of a Signs-based approach may remain the same as what Oralism has been doing. ( MOURA, 2000 MOURA , Maria Cecília . O surdo: caminhos para uma nova identidade . Rio de Janeiro : Revinter , 2000 . , p. 60).

Total Communication has also failed to make the hearing impaired to have accomplishments at school as well as social autonomy, since their presumed conceptions are similar to those of the Oralism. The difference between them lies in the acceptance of signs, taught out of a context and juxtaposed as a way of communication, a practice which is inconceivable for Oralism.

From the early twenty-first century onwards, Bilinguism starts being discussed and regarded as an alternative for Deaf Education. This new approach accepts Sign Language as the deaf’s mother tongue, and will deal with two languages of different nature: Libras, which is based on space and visualization; and the Portuguese language.

The thorniest issue in the relationship between these two languages, which makes this bilinguism peculiar, is that most of the deaf people have no access to Libras, the Brazilian Signs Language, from their early years. A large number of deaf people is not exposed to Libras until they attend their first classes in school.

This is worsened by the fact that, generally speaking, their Libra teachers have learned Libras vocabulary but ignore the grammatical structure of this language, which is visual. These teachers attempt to make a comparison between a Sign Language and the oral language, transforming it in a ‘Signed Portuguese’, which is then recognized as Libras.

We often hear statements such as ‘Libras is the deaf person’s language; Portuguese is the hearing person’s language’. However, talking about ownership of languages is meaningless. Both the hearing person and the deaf person may use both languages.

Misconceptions regarding the meaning of bilinguism pervade the learning environment and some misinterpretations lead to the understanding that practices related to this approach are based on a juxtaposition of languages.

In the same way we realize that, practically speaking, Oralism and Total Communication worked under the same assumptions, in Bilinguism what effectively changes is often the insertion of the Sign Language in school activities. Yet, it is necessary to understand which conception of language one is based at the moment of planning activities and adopting bilingual methods.

Through the research of a few activities found in internet blogs as well as in some books and magazines made available to teachers, we have found some recurrent mistakes and misconceptions with regard to Sign Language. Let us look into the activity as follows.

What we are arguing for here is that the activity presented above prevents us from understanding the difference in modality between these two languages. Furthermore, Libras is being equated with the datilologic alphabet, which shows the lack of understanding about the visual-spacial modality and the conception of languages. Once again Libras is being presented as a code, and the aim of the approach is that this language be understood in its complexity.

The Sign Language cannot be seen merely as a communication code; it is an integral system. And this activity shows us a juxtaposition and the mistaken conception that Libras consists of the manual alphabet. This creates the obscure idea that, in order to create a bilingual activity, an adaptation as shown above will be enough.

Based on the results of her Master’s dissertation, Vieira (2014) VIEIRA , Claudia Regina . Bilinguismo e inclusão: problematizando a questão . Curitiba : Appris , 2014 . shows us that teachers for the deaf still make use of this kind of activity. They believe their students may be helped and learn when both languages are graphically juxtaposed, i.e., through the use of a few signs in texts which are structured in Portuguese.

Even in a context in which bilinguism is formally established, the nature of the activities available seems to be closer to Oralism and Total Communication. They seem to be giving priority to the second language and undermining the mother tongue; transforming Libras with all its complexity into signs which may be expressed visually with illustrations, through the datilologic alphabet or the drawing of signs correspondent to words.

Therefore, the activity described above does not show us the possibility of acquisition of Portuguese as a Second Language; it does not fulfill this role, since the manual alphabet is not enough. The learning process of a second language cannot occur through the juxtaposition of languages, especially because we are talking here about languages of different modalities (auditive and oral – Portuguese and visual space - Libras).

The context of the learning process of the deaf student has a very particular nature: for him/her, Portuguese is a second language. The sign language is not his/her mother tongue, and the learning process does not take place through the building of spontaneous dialogs, but through formal learning in school. Therefore, this learning process will happen through the teaching of written Portuguese, which means the comprehension and the production of written texts. And we have to consider here the effects of such modalities as well as the access to them provided to the deaf students. (SALLES et al, 2004, p. 115).

According to Brito (1995) BRITO , Lucinda Ferreira . Por uma gramática de línguas de sinais . Rio de Janeiro : Tempo Brasileiro: UFRJ , 1995 . , “The structure of Brazilian Sign Language involves primary and secondary parameters which get combined in a sequential or simultaneous way”. In other words, Libras cannot be conceived as graphically-represented signs only, it cannot be reduced to such representations; it is space-visual and its representation goes beyond what is presented in the activities selected above.

In the same way that one should not use Libras signs within the structure of Portuguese, one should not use words from Portuguese within the structure of Libras. The integrity of each language must be kept, and they both should be used in their appropriate contexts.

Adopting the bilingual approach when teaching deaf student requires in-depth knowledge of the two languages involved in this process. But it also requires going beyond the grammatical and structural characteristics of these languages. The importance of each of these languages in the building of concepts and the social construction of the mind should be emphasized.

Our viewpoint, even though it is devoid of theoretical groundwork, is, practically speaking, the basis of all efficient methods for teaching contemporary foreign languages. The core of such methods lies in making the learner familiarized with each linguistic aspect within a context and in a real-life situation. Therefore, a new word can only be introduced depending on a series of contexts in which it will be inserted. Thus, the recognition of a prescribed word will be, from the very beginning, associated and dialectically associated to the factors of contextual mobility, of difference and novelty. Isolated out of a context, simply written in a notebook and learned through association with its equivalent in Russian, becomes, the word becomes, so to speak, a sign; it becomes something unique and, in the process of understanding, the factor of recognition acquires a strong weight. To sum it up, an effect and correct method of practical teaching demands that the form be assimilated not in the abstract language system, i.e., as a form always identical to itself, but in the concrete structure of enunciation, as a flexible and variable sign. ( BAKHTIN, 2009 BAKHTIN , Mikhail Mikhailovich . Marxismo e filosofia da linguagem . 13 . ed. São Paulo : Hucitec , 2009 . , p. 98, our emphasis).

Therefore, it is not enough to present activities in which Libras emerges out of its dialogic context and detached from discourse, or in which Portuguese language is disguised as a Sign Language. One needs to work on each of these languages in their totality and complexity, and attentive to the specific features of each. The activities mentioned above mix up both languages as if they were only one, and fail to work on the mother tongue or on the second language is a way to promote the students’ acquisition of languages.

According to Fernandes (2003) FERNANDES , Eulália . Linguagem e surdez . Porto Alegre : Artmed , 2003 . , the definition of bilinguism demands us to pursue enquiries that transcend this very word, but are related to the way we understand the deaf within their learning process.

How can one talk about bilinguism in education if we put aside issues that involve the concept of education, in its broad and more objective sense? What we deem necessary is a reflection about the deaf person’s educational process, not in the rather strict and pedagogical sense of these words, but with regard to his/her development as individual and his/her participation as an individual in society. Our experience in this area evidently points out towards different directions. On the one hand, there are rather sensible approaches in which the deaf and their culture are respected. Such approaches consider bilinguism in education as a whole, which is never detached from an educational project. This project involves the group of deaf people, including not only the teachers, but the student’s family – no matter whether they are deaf or hearing people. It extends itself to the social environment in which this person lives, in a way that facilitates continuous interlocution between people. (p. 54, our emphasis).

Bilinguism means much more than being exposed to two languages: it is part of a larger project for empowering the deaf student, enabling the school to fulfill their role in transferring knowledge and in promoting students’ autonomy.

When we compare the terms of the Brazilian laws – Law 10436/02 and Decree 5626/05 – which recognize the rights to a bilingual and inclusive education for deaf students – to the documents of National Policy for Special Education on Inclusive Education (2008), we realize that their perspectives are antagonistic. The latter document offers a totally different perspective with regard to the deaf student, as it is explained below by Lodi (2013) LODI , Ana Claudia Balieiro . Educação bilíngue para surdos e inclusão segundo a Política Nacional de Educação Especial e o Decreto nº 5.626/05 . Educação e Pesquisa , São Paulo , v. 39 , n. 1 , p. 49 - 63 , jan./mar . 2013 . Disponível em: < http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ep/v39n1/v39n1a04.pdf> . Acesso em: 16 maio 2016 .

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ep/v39n1/v39n1a...

:

By reading the term of the Decree, the fundamental role played by Libras in bilingual education becomes evident. This creates the demand for ‘alternative systems for the evaluation of the syllabus taught in Libras, as long as it is adequately recorded in video or in other electronic and technological media […] in the Document of the National Policy for Special Education, this kind of education is characterized as “school teaching in Portuguese language and in Libras… and Portuguese as a second language must be taught in its written form to the Deaf students. Therefore, opposing to what the Decree states, it remains unclear, in this Document, which language should be used by the teacher in the inclusive classes (Portuguese or Libras) for deaf students. Also, the Document is not taking into account the fact that these two languages cannot be taught simultaneously (p. 55).

The assumption that Lodi is criticizing here, concerning what is expressed in the laws, is actually found in the activities made available in the internet blogs, where the simultaneous use or the juxtaposition of languages is being considered as bilinguism.

All these findings corroborate the misunderstanding of the proposals, which contributes to maintaining deaf students in a serious disadvantage in schools, even if, legally speaking, their linguistic rights are granted.

Final Considerations

The panorama on the history of Deaf Education provided in our article leads us to the conclusion that changes in terminology do not necessary imply conceptual or practical changes in the activities performed with the deaf students in the classroom.

Although it is clear that bilinguism will have a positive impact on the learning process of deaf students, all practices adopted under this approach up to the present moment are still imbued with conceptions from Oralism and Total Communication. This becomes evident in the analyses of pedagogical guidelines, activities and blogs that regard themselves as bilingual.

Points of contention in the social realm imply adjustments and idiosyncrasies during the enquiry process, and the researcher must be tactful when entering this field of investigation, with regard to the way that different educational places are built. Academics are supposed to engage in a constructive dialogue with schools, so that deaf students may enjoy positive benefit from their learning process, taking into account their linguistic specificity and the culture where they belong. At the same time, the responsibility of schools in their learning process of written Portuguese cannot be neglected.

The results of a bilingual education really have made it clear that deaf people are as capable of learning as their hearing peers. Teachers are shown that it is possible to work in a different manner by exploring the visual conditions which are appropriate for the community of deaf. And, finally, deaf students are shown that school is, indeed, a place for them.

Referências

- BAKHTIN , Mikhail Mikhailovich . Marxismo e filosofia da linguagem . 13 . ed. São Paulo : Hucitec , 2009 .

- BRAGA , Mário Joel da Silva . Programa de estruturação sistematizada da linguagem para deficientes auditivos . São Paulo : Secretaria de Educação Municipal , 1983 . Mimeo .

- BRASIL . Decreto nº 5626. Regulamenta a Lei nº 10.436, de 24 de abril de 2002, que dispõe sobre a Língua Brasileira de Sinais – Libras, e o art. 18 da Lei nº 10.098, de 19 de dezembro de 2000 . Diário Oficial da União , Brasília, DF , 22 dez . 2005 .

- BRASIL . Lei nº 13.146, de 6 de julho de 2015. Dispõe sobre a Lei brasileira de inclusão da pessoa com deficiência . Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil , Brasília, DF , 06 jul . 2015 . Disponível em: < http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2015/Lei/L13146.htm> . Acesso em: 25 mar. 2016 .

» http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2015/Lei/L13146.htm> - BRASIL . Ministério da Educação . Secretaria de Educação Continuada, Alfabetização, Diversidade e Inclusão . Política nacional de educação especial na perspectiva da educação inclusiva . Brasília, DF : MEC , 2008 . Disponível em: < http://portal.mec.gov.br/arquivos/pdf/politicaeducespecial.pdf > . Acesso em: 18 maio 2016 .

» http://portal.mec.gov.br/arquivos/pdf/politicaeducespecial.pdf - BRASIL . Ministério da Educação . Secretaria de Educação Especial . Lei nº 10.436 de 24 de abril de 2002. Dispõe sobre a Língua Brasileira de Sinais – Libras e dá outras providências . Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil , Brasília, DF , 24 abr . 2002 .

- BRITO , Lucinda Ferreira . Integração social e educação de surdos . Rio de Janeiro : Babel , 1993 .

- BRITO , Lucinda Ferreira . Por uma gramática de línguas de sinais . Rio de Janeiro : Tempo Brasileiro: UFRJ , 1995 .

- CALDEIRA , José Carlos Lassi . Exercícios psicomotores e psicopedagógicos anteriores à alfabetização: Programa Comunicar . Belo Horizonte : Clínica-Escola Fono , 1998 .

- COUTO , Álpia . Posso falar: orientação para o professor de deficientes da audição . 2 ed. Rio de Janeiro : EDC , 1986 .

- DORZIAT , Ana . O outro da educação: pensando a surdez com base nos temas Identidade/Diferença, Currículo e Inclusão . Petrópolis : Vozes , 2009 .

- FERNANDES , Eulália . Linguagem e surdez . Porto Alegre : Artmed , 2003 .

- FERNANDES , Sueli . Educação de surdos . 2 . ed. Curitiba : Ibpex , 2011 .

- FERNANDES , Sueli ; MOREIRA , Laura Ceretta . Políticas de educação bilíngue para surdos: o contexto brasileiro . Educar em Revista , Curitiba , n. spe-2 , p. 51 - 69 , 2014 . Disponível em: < http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.37014> . Acesso em: 2 abr. 2018 .

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.37014> - GESUELI , Zilda Maria . A escrita como fenômeno visual nas práticas discursivas de alunos surdos . In: LODI , Ana Claudia Baliero et al . ( Org .) . Leitura e escrita no contexto da diversidade . Porto Alegre : Mediação , 2004 . p. 39 - 48 .

- GOLDFELD , Márcia . A criança surda: linguagem, cognição: uma perspectiva sócio interacionista . São Paulo : Plexus , 1997 .

- GUARINELLO , Ana Cristina . O papel do outro na escrita de sujeitos surdos . São Paulo : Plexus , 2007 .

- HONORA , Márcia . Inclusão educacional de alunos com surdez: concepção e alfabetização: ensino fundamental, 1º ciclo . São Paulo : Cortez , 2014 .

- KARNOPP , Lodenir Becker ; PEREIRA , Maria Cristina da Cunha . Concepções de leitura e escrita e educação de surdos . In: LODI , Ana Claudia Baliero et al . ( Org .) . Leitura e escrita no contexto da diversidade . Porto Alegre : Mediação , 2004 . p. 33 - 38 .

- LACERDA , Cristina Broglia Feitosa ; SANTOS , Lara Ferreira . Tenho um aluno surdo, e agora? Introdução a Libras e educação de surdos . São Paulo : EdUFSCar , 2013 .

- LODI , Ana Claudia Balieiro . Educação bilíngue para surdos e inclusão segundo a Política Nacional de Educação Especial e o Decreto nº 5.626/05 . Educação e Pesquisa , São Paulo , v. 39 , n. 1 , p. 49 - 63 , jan./mar . 2013 . Disponível em: < http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ep/v39n1/v39n1a04.pdf> . Acesso em: 16 maio 2016 .

» http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ep/v39n1/v39n1a04.pdf> - LOPES , Sonia de Castro ; FREITAS , Geise de Moura . A construção do projeto bilíngue para surdos no Instituto Nacional de Educação de Surdos na década de 1990 . Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos , Brasília, DF , v. 97 , n. 246 , p. 372 - 386 , ago . 2016 . Disponível: < http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S2176-6681/374713703> . Acesso em 10 abr. 2018 .

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S2176-6681/374713703> - MOURA , Maria Cecília . O surdo: caminhos para uma nova identidade . Rio de Janeiro : Revinter , 2000 .

- SÁ , Nídia Regina Limeira de . Cultura, poder e educação de surdos . Manaus : Universidade Federal do Amazonas , 2002 .

- SÁ , Nídia Regina Limeira de . Educação de surdos: a caminho do bilinguismo . Niterói : EdUFF , 1999 .

- SALLES , Heloísa Maria Moreira Lima et al . Ensino de língua portuguesa para surdos: caminhos para a prática pedagógica . Brasília, DF : MEC , 2004 . ( Programa Nacional de Apoio à Educação dos Surdos, v. 2 ).

- SERPA , Laura . Libras educando surdos . Blogspot online . Disponível em: < http://libraseducandosurdos.blogspot.com/2016/08/abolicao-dos-escravos.html?m=1> . Acesso em: 23 ago. 2018 .

» http://libraseducandosurdos.blogspot.com/2016/08/abolicao-dos-escravos.html?m=1> - SKLIAR , Carlos ( Org .) . Atualidade da educação bilíngue para surdos . v. 1-2 . Porto Alegre : Mediação , 1999 .

- SOARES , Maria Aparecida Leite . A educação do surdo no Brasil . Campinas : Autores Associados ; Bragança Paulista : Edusf , 1999 .

- VIEIRA , Claudia Regina . Bilinguismo e inclusão: problematizando a questão . Curitiba : Appris , 2014 .

- VYGOSTKY , Lev Semyonovich . Obras escogidas II: pensamiento y lenguaje conferencias sobre psicología . Madrid : Machado Grupo de Distribución , 2014 .

-

3

- In the course “Education with a major in Audiocommunication for the Hearing Impaired, we would learn how to ‘put’ phonemes in our students, for example in activities such as putting up something on their lips so that they might be able to distinguish the articulation of the phoneme /m/, and by doing so, be able to learn it.

-

4

- https://pedagogiaaopedaletra.com/apostila-de-alfabetizacao-metodo-fonico/ , p.1 (access on August, 23, 2018).

-

5

- [Also: brace and bit]: A drilling tool with a crank handle and a socket to hold a bit. (From: The New Oxford Dictionary of English).

-

6

- NORTHERN, J. & DOWNS, M. - Hearing in Children . Maryland: The Williams and Wilkins Company, 1975.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

03 Dec 2018 -

Date of issue

2018

History

-

Received

02 May 2017 -

Reviewed

14 Mar 2018 -

Accepted

24 Apr 2018

Source: Handbook ‘Literacy Learning through the Phonic Method’, page 1 (access on August 23 rd , 2018)

Source: Handbook ‘Literacy Learning through the Phonic Method’, page 1 (access on August 23 rd , 2018)  Source: (

Source: (  Source: http://libraseducandosurdos.blogspot.com/2016/08/abolicao-dos-escravos.html?m=1 (access on August 23rd, 2018).

Source: http://libraseducandosurdos.blogspot.com/2016/08/abolicao-dos-escravos.html?m=1 (access on August 23rd, 2018).

Source: (

Source: (