ABSTRACT

We selected eight toy suppliers from three emerging markets: China, Vietnam, and India, as research objects and adopted grounded analysis and multi-case study to explore the effectiveness, interrelationship, and function contexts of the global supply chain governance model. The study found that (1) contractual governance and relational governance affect the performance of suppliers’ social responsibilities and the overall performance of the supply chain; (2) the relationship between the two governance models can have a substitute view and a complementary view. They have similar functions and unique functions, which can have different advantages under different circumstances; and (3) in global supply chain governance of emergent markets, three combinations of the two governance models effectively promote social responsibility and performance: the combination of high relational and low contractual governance, the combination where relational and contractual governance are balanced, and the combination of high contractual and low relational governance. The conditions required to select an appropriate combination of governance models for a supply chain include the supplier’s capability, the cooperation time and experience of the two parties, the goal congruence, and the institutional distance. The selection of an adequate combination for supply chain governance must consider the complexity and variability of the emerging market environment. Additionally, the weight of contractual governance and relational governance should be reasonably selected and dynamically adjusted to effectively play their respective roles and functional superposition. Our research may reduce exploitation in global supply chains, accelerate green transitions, and improve livelihoods and strengthen long-term resilience by aligning profit motives with social and environmental good.

Keywords:

sustainable supply chain governance; supply chain governance; social responsibility; supply chain management; case study.

RESUMO

O presente estudo tem por objeto oito fornecedores de brinquedos de três mercados emergentes - China, Vietnã e Índia. Por meio de análise fundamentada e estudos multicaso, a pesquisa explora os contextos de eficácia, inter-relação e função do modelo global de governança da cadeia de suprimentos, constatando que: (1) a governança contratual e a governança relacional afetam o desempenho das responsabilidades sociais dos fornecedores e, consequentemente, o desempenho geral da cadeia de suprimentos; (2) a relação entre os dois modelos de governança é tanto de substituição quanto de complementaridade, sendo que possuem tanto funções semelhantes quanto únicas, o que lhes permite oferecer vantagens distintas em diferentes circunstâncias; (3) na governança global da cadeia de suprimentos em mercados emergentes, as combinações dos dois modelo de governança que efetivamente promovem a responsabilidade social e o desempenho são três: a combinação de alta governança relacional e baixa contratual; a combinação onde governança relacional e contratual estão em equilíbrio; e a combinação de alta governança contratual e baixa relacional. As condições para a seleção da combinação mais adequada incluem: a capacidade do fornecedor, o tempo e experiência de cooperação entre as partes, a congruência de objetivos e o distanciamento institucional. A seleção da combinação mais adequada para a governança das cadeias de suprimento deve também considerar a complexidade e variabilidade do ambiente de mercados emergentes, sendo que o peso da governança contratual e da governança relacional deve ser apreciado de modo racional e ajustado dinamicamente para que desempenhem efetivamente seus respectivos papéis e superposição funcional. A contribuição e o impacto social da nossa pesquisa podem reduzir a exploração nas cadeias de suprimentos globais, acelerar transições ecológicas, melhorar os meios de subsistência e fortalecer a resiliência em longo prazo, alinhando lucratividade e bem social e ambiental.

Palavras-chave:

governança sustentável da cadeia de suprimentos; governança da cadeia de abastecimento; responsabilidade social; gestão da cadeia de abastecimento; estudo de caso.

RESUMEN

Se seleccionaron ocho proveedores de juguetes de tres mercados emergentes, china, Vietnam e india, como objeto de investigación, utilizando métodos de análisis arraigados y estudios de casos múltiples para explorar la efectividad, la interrelación y el contexto funcional del modelo de gobernanza global de la cadena de suministro. El estudio encontró que (1) la gobernanza contractual y la gobernanza de las relaciones afectan el rendimiento de la responsabilidad social de los proveedores, lo que a su vez afecta el rendimiento general de la cadena de suministro.(2) La relación entre los dos modelos de gobernanza es tanto de sustitución como de complementariedad. Estos poseen tanto funciones similares como funciones únicas, lo que puede generar ventajas diferenciadas según las circunstancias.(3) En la gobernanza global de cadenas de suministro en mercados emergentes, las opciones de gobernanza que promueven efectivamente la responsabilidad social y el desempeño son tres combinaciones: combinación de alta relación y bajo contrato; combinación equilibrada entre relación y contrato; combinación de alto contrato y baja relación. Los criterios de selección para estas combinaciones incluyen: la capacidad del proveedor, el tiempo y experiencia de cooperación entre las partes, la congruencia de objetivos y la distancia institucional.Dada la complejidad y variabilidad del entorno de los mercados emergentes, estos factores contextuales deben considerarse simultáneamente en la gobernanza de la cadena de suministro. Además, el peso asignado a la gobernanza contractual y relacional debe seleccionarse racionalmente y ajustarse dinámicamente para que puedan desempeñar efectivamente sus respectivos roles y lograr una superposición funcional óptima.El aporte y el impacto social de nuestra investigación pueden reducir la explotación en las cadenas de suministro globales, acelerar las transiciones ecológicas, mejorar los medios de vida y fortalecer la resiliencia a largo plazo, alineando los motivos de lucro con el bien social y ambiental.

Palabras clave

gobernanza sostenible de la cadena de suministro; gobernanza de la cadena de suministro; responsabilidad social; gestión de la cadena de suministro; estudios de casos.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, research on supply chain management has emphasized business ethics (Quarshie et al., 2016). How to fulfill social responsibility and achieve sustainability through supply chain governance has become a hot issue (Sodhi & Tang, 2018). However, due to information asymmetry and unequal distribution of rights and responsibilities among different entities in the supply chain, it is easy to induce “indirect greenwashing” and other opportunistic behaviors, which pose significant risks to the governance of supply chains (Pizzetti et al., 2021). The global supply chain is dominated by multinational enterprises due to the gap in geography, information, power, and compliance with suppliers (Boström et al., 2015), which makes it more difficult to achieve sustainability goals (Jia et al., 2020).

Emerging markets play a key role in the global supply chain due to their large market development potential and low labor costs. However, due to the influence of geographical distance and cultural differences, opportunistic behaviors are more prominent in these economies (Yang et al., 2018). Environmental pollution, labor, and safety problems are also more complex, so global supply chain governance (GSCG) for emerging market’ suppliers is more difficult (Soundararajan et al., 2021). A typical example is the global recall of tens of millions of toys by Mattel, America’s biggest toy company, after a supplier found excessive levels of heavy metals in toy paint. However, the current focus on the uniqueness and differences of emerging market governance is insufficient (Soundararajan et al., 2021), and scholars call for more research on the environmental and social impacts of emerging markets and supply chains (Seuring et al., 2022).

As for the research on the relationship between contractual governance and relational governance, which are two models of supply chain governance, there are still large divergences in the current research, which can mainly be divided into three different views: substitute view (Huang et al., 2014), complementary view (Um & Oh, 2020), and simultaneous view (Wang et al., 2023). Meanwhile, no matter which kind of relationships are involved, the two governance models coexist in the same supply chain governance. As for the many possible combinations of the two governance models in emerging markets, one might question whether there is an optimal combination applicable to all situations, or if the adoption of different combinations to specific situations is the appropriate path to follow. Also, it is worth exploring whether, throughout the development of the supply chain, one governance model will grow while the other declines, or if they will develop together. There is a lack of in-depth analysis on how these two different governance models can combine to improve governance effectiveness in emerging markets.

Given the controversy and insufficiency in the current research on supply chain governance, this paper comprehensively considers macro and micro factors such as the environmental differences in countries, cooperation experience between supply chain subjects and suppliers’ own capabilities. It selects eight suppliers from three emerging markets: China, India, and Vietnam. Through grounded analysis and multiple case studies, we explore the internal mechanisms and contexts of contractual governance and relational governance in emerging markets and analyze the relationship between these two governance models. We explore the possible combinations of these two models and conditions observed to select such combinations in order to achieve high social responsibility and performance, thus helping to reveal the uniqueness and effectiveness of supply chain governance in emerging markets.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Definition of sustainability and sustainable supply chain governance

The World Commission on Environment and Development defines sustainability as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability to meet the needs of future generations.” This definition integrates social, environmental, and economic issues. Environmental sustainability includes resource utilization and its impact on the natural environment; social sustainability considers the health and well-being of people in the supply chain and its impact on society; economic sustainability emphasizes the economic growth and development model with low input, low energy consumption, and high output (Huq et al., 2016).

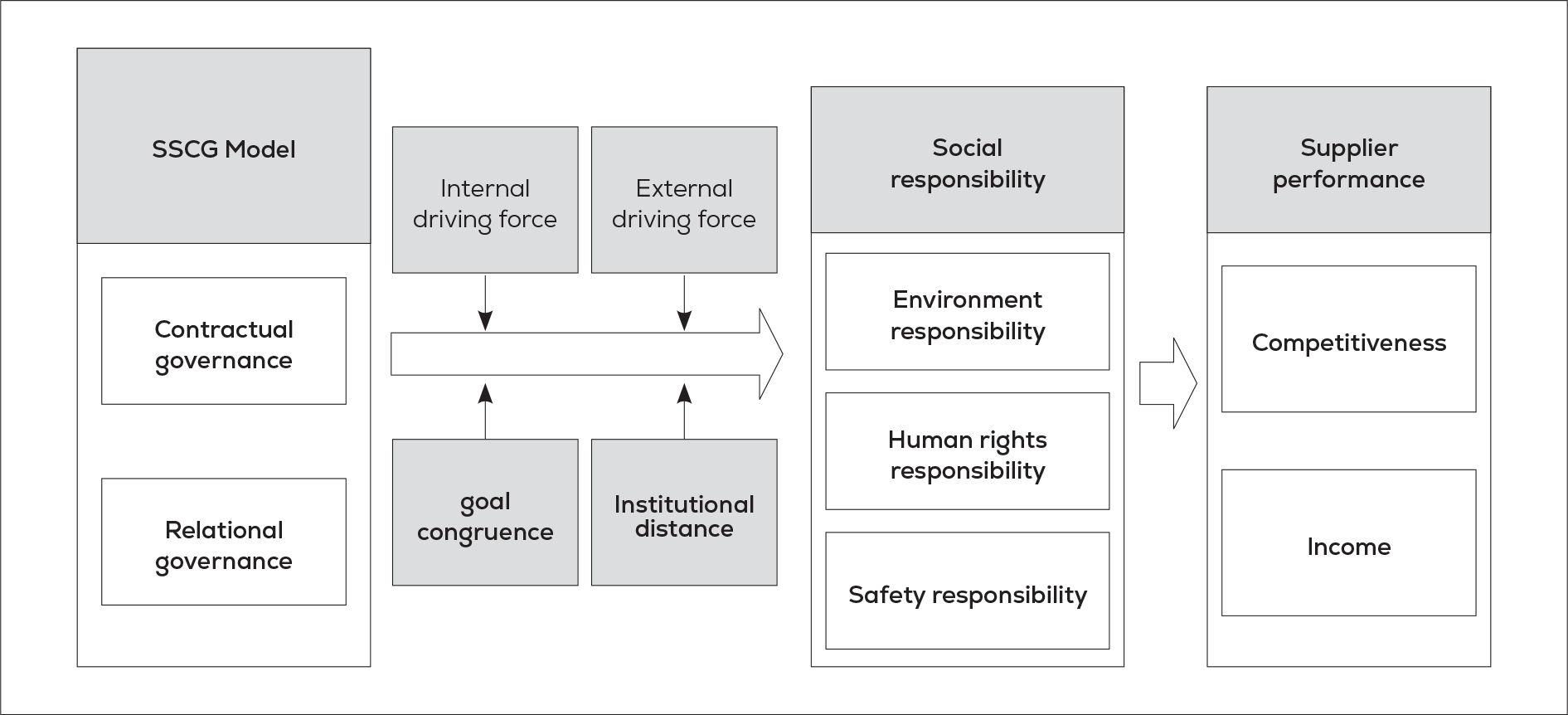

Sustainable supply chain governance (SSCG) refers to the practices, initiatives, and processes that core companies use to manage partnerships within supply chains to collectively improve environmental and social conditions at all stages of the supply chain (Formentini & Taticchi, 2016), maintain the its continuous and stable operation (Alexander, 2020), and improve its overall sustainability performance. SSCG emphasizes that the behavior and results of governance need to consider the three aspects of economic, social, and environmental sustainability, paying special attention to the long-term balance between self-interest decision-making, and interdependence among enterprises in the supply chain (Dolci et al., 2017).

Advantages, disadvantages, and interrelationships of governance models in sustainable supply chains

Supply chain governance aims to establish a benign resource allocation and benefit coordination mechanism inside and outside the supply chain. Therefore, the two important mechanisms to shape SSCG are cooperation and formalization. Some scholars have divided SSCG into two models: contractual governance and relational governance (Pfaff et al., 2023). Contractual governance is based on the transaction cost theory, which records and defines the capability, cost, complexity, and coding of transactions in the form of contracts. Relational governance is based on a perspective that emphasizes mechanisms based on flexibility, interrelationships, solidarity, information exchange, collaboration, commitment, cooperation, and integration (Dolci et al., 2017). An analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of the two governance models, reveals that contractual governance is conducted in the form of standards and norms, so it has better transaction cost advantages than relational governance (Jia et al., 2018). However, the implementation of contracts brings relatively high supervision costs, and relying purely on economic incentives to select and maintain supplier relationships is not enough to support the implementation of sustainable development goals (Soundararajan & Brown, 2016). Thus, the effect of contractual governance is limited. Recently, scholars have emphasized and respected the important role of trust-based relational governance for sustainable supply chains.

The relationship between contractual and relational governance is divided into three categories: substitute view, complementary view, and simultaneous view. Scholars who consider the relationship from the substitute view believe that both contractual governance and relational governance can improve the effect of supply chain governance by reducing uncertainty. However, when areas such as trust are still low among different subjects of the supply chain, they tend to formulate and use more stringent contract terms to reduce opportunism and avoid uncertainty (Huang et al., 2014). Scholars who consider the complementary view believe that contractual governance and relational governance differ greatly in use (formal/informal), action (control/ collaboration), cost (communication cost/supervision cost), and efficiency. Trust contributes to the communication and sharing of knowledge/information and is more conducive to the continuous improvement of supplier performance, which can complement the role of formal contracts (Zheng et al., 2008). The two governance models can work together to improve effectiveness (Um & Oh, 2020). Scholars with a simultaneous view argue that contractual and relational governance have substitute and complementary roles (Sánchez et al., 2012). They have substitute roles from the perspective of the horizontal time node, but they are complementary from the perspective of vertical change of contract/trust over time (Wang et al., 2023).

Prerequisite and governance performance of the SSCG model

The choices of governance models are usually affected by a variety of factors. Scholars have studied the institutional environment, the complexity and capacity needs of transactions, and the types and levels of relationships between supply chain subjects. Firstly, from the analysis of the institutional environment, the maturity and perfection of laws and regulations affect the choice and effect of the use of governance models. When the legal environment becomes more standardized, the supply chain places greater importance on the role of contractual governance (Zhang et al., 2020). Cultural distance increases the risk of opportunism by inhibiting the implementation of contracts. Therefore, when the cultural distance between the two sides of the supply chain is large, enterprises can strengthen contract design to curb opportunism (Seuring et al., 2022). Secondly, based on the complexity and capability requirements of transactions within the supply chain, dealing with highly complex and capable suppliers requires more relational governance (Pfaff et al., 2023). Finally, negative relationship experiences may lead to a more contractual SSCG, and the trust of buyers and sellers tends to a more relational SSCG (Belhadi et al., 2021).

In terms of measuring indicators of supply chain cooperation performance, scholars have adopted subjective/objective indicators, qualitative/quantitative indicators, absolute/relative indicators, and financial/non-financial indicators. These indicators can be divided into two categories: operational performance and financial performance. Operational performance includes quality, cost, supply chain partner reliability, and flexibility. Financial performance includes the profitability of the partnership, the price of the final product, and sales growth. In the study on the effects of contractual and relational governance on supply chain cooperation performance, some scholars pointed out that both relational and contractual governance contribute to supply chain cooperation performance (Zhang & Aramyan, 2009). However, there are empirical studies with different conclusions: relational governance has a positive impact on supply chain performance, while contractual governance has no significant effect on supply chain performance (Feng et al., 2020). Some scholars found an inverted U-shaped relationship between contractual governance and supply chain cooperation performance (Huang et al., 2014).

Contexts of the SSCG model’s role

Attributes of supply chain enterprises, the nature of transactions, and the supply chain environment form important contexts influencing the effect of contractual and relational governance. Firstly, the capability of the supplier and organizational support have a significant impact on the role of the supply chain governance model. With strong manufacturing capacity, the supplier will better execute the contract, thus improving the supply chain performance (Sánchez et al., 2012). Some studies have pointed out that if organizations provide employees with support in human resources and other aspects, employees develop a commitment to improving work efficiency, which means that organizational support has a moderating effect on the impact of SSCG on economic performance (Zhang, 2024). Secondly, the goal congruence of all parties in the supply chain (Um & Oh, 2020), the relationship experience of buyers and suppliers, and the length of cooperation time (Cao & Lumineau, 2015) play a moderating role. Goal congruence contributes to better communication and coordination, and a positive relationship experience helps to strengthen trust. Both can improve the efficiency and effect of cooperation among all parties in the supply chain, reducing opportunistic behaviors. Thirdly, differences in cultural traditions and beliefs (Soundararajan & Brown, 2016) and institutional distance are important contexts for the effects of SSCG on cooperation performance.

RESEARCH METHODS AND DATA SOURCES

Research methodology and case selection

A case study is a qualitative research method that applies the “why” and “how” research questions (Eisenhardt, 1989). The multiple case study approach adopted here, however, has stronger external validity and is highly respected by scholars (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007). Based on the principle of typicality and theoretical sampling, we investigate the toy industry, which has a huge global supply chain. We examine the industry in China, Vietnam, and India, three emerging markets with large differences in their political system, culture, and development level, and combine the similarities and differences of enterprise capabilities and cooperation time. Eight suppliers were selected. Table 1 shows the details of the enterprises studied.

Data were collected through face-to-face, online, and telephone interviews, supplemented by questionnaires. During the interview process, the original data were recorded with the interviewees’ consent. In addition, secondary data were obtained through sources such as the company’s official website and internal documents. The interviewees were mainly senior executives responsible for corporate social responsibility management in supplier companies, and each interview lasted between 1-2 hours. Table 2 presents details of the implementation of the interviews.

Classification of the Combinations of Governance Models and the Companies’ Social Responsibility and Performance

EXPLORATORY CASE STUDIES ON SUPPLY CHAIN GOVERNANCE, SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY, AND SUPPLIERPERFORMANCE

Data coding

The relevant data collected were coded using the grounded theory method. Grounded theory focuses on building theories through a systematic, iterative process of comparing, encoding, and analyzing data, with a key element being the continuous comparison and analysis of data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This paper follows the three-stage coding process proposed by Strauss and Corbin (1990). The coded data were obtained from interviews with eight enterprises held in August and September 2023, and from secondary sources comprising over 90,000 words recorded. The theoretical framework emerged after continuous data sorting, classification, and induction. Theoretical saturation was reached when the data supported the theme of this research, no new constructs and relationships emerged in the coding process (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), and the coding work was over. It should be further noted that we completed all the coding work independently, the results were compared after the coding, and the coding results had good consistency. After coding was completed, we explained the coding results to all interviewees and asked them to verify them according to the actual situation of their companies, which they highly approved, thus enhancing the robustness and reliability of the research results.

Analysis of the relationship between SSCG, social responsibility, and performance

The research results, combined with the original data, provided appropriate elements for an in-depth analysis of the action logic and contexts of SSCG.

Action logic of the SSCG model

In addition to the mutual agreement and protection of product quality, delivery time, price, and other aspects, contractual governance and relational governance both involve the provisions and requirements of social responsibility. They have an important impact on suppliers’ environmental protection, safety, and employees’ human rights and other responsibilities. Guidelines and training offered by buyers affect the suppliers’ level of social responsibility. Contractual governance uses formal contracts to establish mandatory constraints and performance requirements for suppliers through explicit provisions on social responsibility. Thus suppliers can continuously improve environmental protection, safety, and employees’ rights and interests in order to meet the contract terms and improve social responsibility. On the other hand, relational governance improves suppliers’ capability through training, guidance, feedback, and communication, which also contribute to social responsibility. The development of trust and relationships is conducive to a) the negotiation of practical difficulties related to social responsible behavior, b) the solution of problems within the supply chain, and c) cooperation.

The enhancement of social responsibility practices to address issues such as environmental protection, labor human rights, and safety by suppliers has a positive impact on employees’ satisfaction and loyalty, production efficiency, and product quality and competitiveness. Additionally, CSR influences the buyers’ trust and impacts sales. In other words, CSR affects the companies’ financial and non-financial performance and plays an important intermediary role between the two models of SSCG and performance in cooperative arrangements. Thus, the action logic of the SSCG model (contractual governance or relational governance) is developed in a context of improvement of both social responsibility practices and corporate performance.

Contexts of the role of the SSCG model

The analysis of the contexts around the impact of contractual and relational governance on suppliers’ social responsibility used four important variables that have moderating effects: suppliers’ internal driving force, external driving force, goal congruence between buyers and suppliers, and institutional distance between countries.

-

1. Supplier’s internal driving force. The supplier is the ultimate implementer of social responsibility in the supply chain. Therefore, the supplier’s internal driving force to engage in social responsibility and take practical actions is crucial to successful CSR. The interview data revealed that the first impact is the consciousness and desire for execution by the company’s management. An interviewee stressed that “if the awareness of the management is not strong, it is difficult for the people below to have the willingness to implement.” The second impact is the influence of managers’ learning motivation. According to one of the interviewees, “If I don’t have the desire to understand these requirements of social responsibility, I can’t be trained to learn them.” Finally, there is the impact on the entire corporate culture. An interviewee mentioned: “corporate culture determines the attitude of a company in fulfilling social responsibility.”

-

2. External driving force. This variable can be divided into two aspects: pressure from local government departments and the driving force of third-party audits designated by buyers. Pressure from government departments refers to suppliers’ compliance with laws and regulations, and supervision by the host country. The local government has a duty to exert such pressure and encourage companies’ actions toward social responsibility. According to an interviewee, “In terms of environmental protection, I think the government plays a more important role.” Regarding the aspect of the driving force of third-party audits, they mainly play a role in providing qualification recognition according to the standard audit and help suppliers plan and improve the level of social responsibility implementation by providing clear standards. An interviewee mentioned: “Third-party audit, this is also very important...... It can help us plan for human rights, security, even environmental protection.”

-

3. Goal congruence between buyer and supplier. The supply and demand sides of the supply chain are different entities, which may lead to incompatible incentives and unequal rights and obligations regarding social responsibilities. These differences may easily induce opportunism and other behaviors, damaging the buyer’s brand reputation. Since strict contracts or supervision may not guarantee that both parties engage effectively, buyers and suppliers must reach a consensus on the need for cooperation and outcomes to establish a consistent goal, especially if the supplier is the primary executor of social responsibility practices. The degree of goal congruence between buyers and suppliers impacts the level of social responsibility. Based on the interviews and coding process, goal congruence includes two dimensions: behavioral congruence (cooperation/task congruence) and outcome congruence (interest/ development congruence).

-

4. Institutional distance. In the global supply chain, differences in economic environments, laws, and cultural beliefs between the countries of --suppliers and buyers lead varying understandings of the relevant provisions regarding social responsibilities in contracts, significantly affecting the actual implementation of CSR practices by suppliers. For the interviewees, “Suppliers must take into account the local culture, local laws, and regulations when implementing social responsibility, otherwise it can actually cause some disruption to business.”

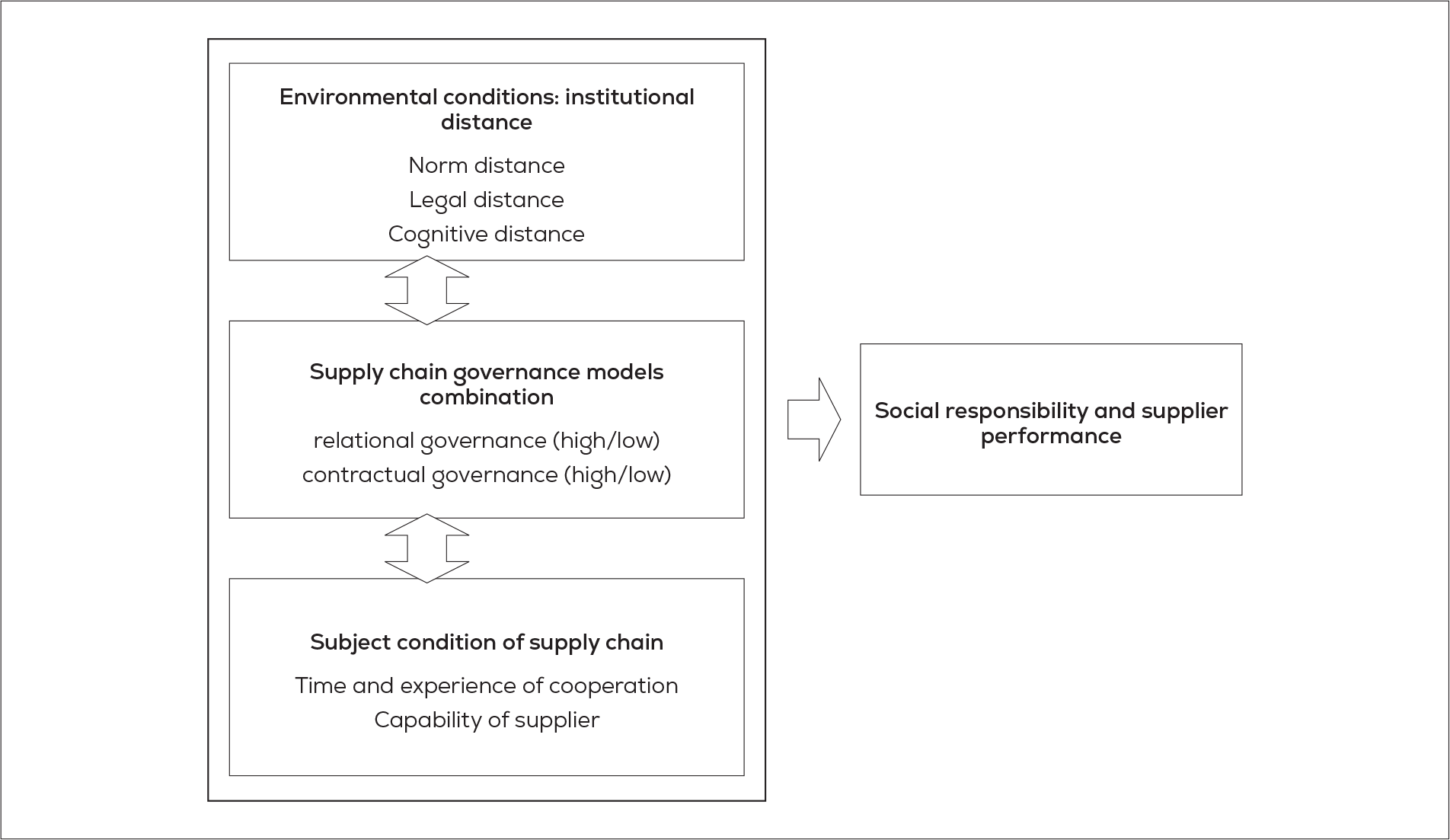

Conditions required for different combinations of SSCG models

Both contractual governance and relational governance play an important role regarding suppliers’ social responsibility. However, their implementation advantages differ, indicating that these two governance models are not an either/or choice, but can complement each other. Thus, various combinations of high and low contractual and relational governance models are formed.

How are the two governance models combined? Is there an optimal combination for promoting social responsibility and improving the performance of the supply chain, or is there a differentiated combination that fits different contexts? We found that the institutional distance between the two countries in which the buyers and suppliers are located, the cooperation time between the two parties in the supply chain, and the capability of the suppliers themselves are three factors that have significant impacts on how to combine contractual and relational governance and influencing the engagement in social responsibility.

This study examined eight companies from three emerging markets - China, Vietnam, and India - to further analyze and compare the effective combination of SSCG models, the conditions required for each model, social responsibility, and the performance of SSCG.

Specific conditions and performance of the combination of high relational and low contractual governance

The suppliers LX, WHS, SL, and YZ present a combination of high relational and low contractual governance (Table 5). This combination of governance emphasizes communication, development of cooperative relationships, building trust, training, and feedback as the main strategies of high relational governance, and the contract is only the basic foundation between the two parties.

As elements characteristic of relational governance, the study found that LX and WHS demonstrate strong capabilities and long-term business contacts, which led them to build an evolving relationship with buyers. Their buyers value relationship development at the company level, good communication, competency-based trust, and feedback evaluation to coordinate both sides of the supply chain. For SL and YZ, we observed that, in addition to relationship development and trust building, the training they get from buyers on-site, timely communication, and an incentive feedback system are crucial. Under the background of strong suppliers’ capabilities, long cooperation time between suppliers and buyers, and small regulative and cognitive distance, the result is satisfactory social responsibility (according to buyers’ standards) and improved performance (assessed based on sales).

Specific conditions and performance of the combination where relational and contractual governance are balanced

In the case of companies ST and JYP, their buyers establish a combination where relational and contractual governance are balanced. On the one hand, this combination focuses on the legally binding force of contracts between the two parties, while on the other, it emphasizes the communication, interaction, supervision, and inspection typical of relational governance.

According to the different proportions of relational and contractual governance models, this combination can be further subdivided into slightly more contractual (ST company) and slightly more relational (JYP company). When slightly more contractual, this combination indicates that the position and role of the contract in governance is somewhat higher, while relational governance is still continuously developed, strengthening communication, feedback, and developing personal relationships within the parties. The conditions required for a slightly more contractual combination are strong suppliers’ capability, short cooperation time between buyers and suppliers, and small regulative and cognitive distance. The conditions required for the partial relational balanced combination are the normal capability of the supplier, the short cooperation time between buyer and supplier, and the large legal and cognitive distance.

Specific conditions and performance of the combination of high contractual and low relational governance

Two cases of the combination of high contractual governance and low relational governance are AFC and FKL. This combination relies heavily on contracts and highlights this mechanism while it reduces the relevance of training, communication, relationship development, and trust between buyers and suppliers. The specific conditions are the strong capability of suppliers, the short cooperation time between suppliers and buyers, and the large distance between regulation and cognition. Specifically, due to the short cooperation time and the large institutional distance between the two sides of the supply chain, buyers adopt the contract with formal legal constraints as the main governance strategy and pay more attention to their capabilities in the selection of suppliers. Seen from the governance results, the companies’ social responsibility and performance are good.

Discussion

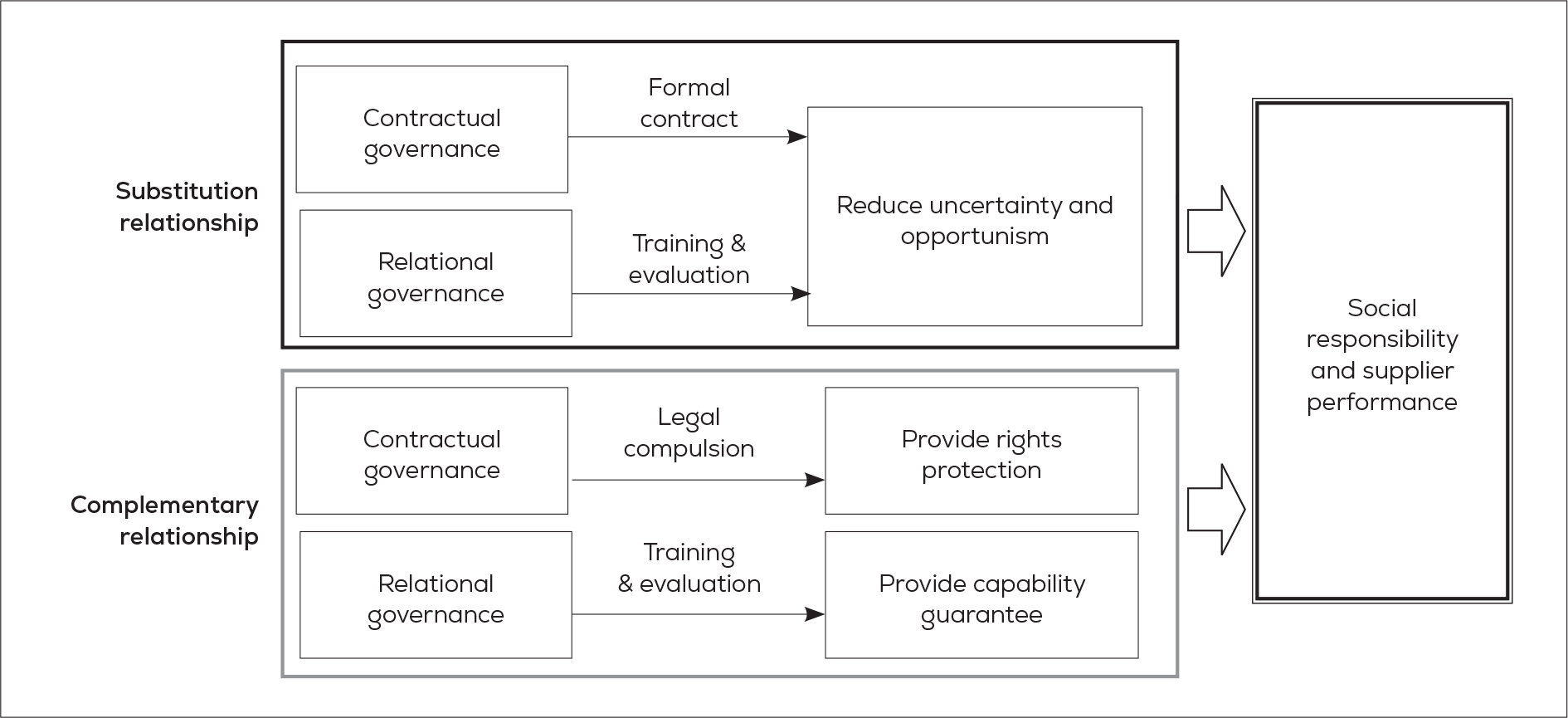

Relationship and combined effect of different SSCG models

As two SSCG models, contractual governance and relational governance have similar and overlapping functions in promoting social responsibility and overall performance. From the core issue of reducing uncertainty and opportunistic behavior in supply chain governance, scholars point out that the relationship between the two governance models is one of substitution (Cao & Lumineau, 2015; Huang et al., 2014). The results show that, in terms of specific implementation and internal function, contractual governance is clearly defined in terms of product quality, price, social, economic, and environmental responsibility through relevant provisions and requirements of contract terms through a legally binding formal contract as the basis for governance. On the other hand, relational governance focuses on the trust and relationship development between buyers and suppliers in the supply chain. This approach fosters cooperative consensus and goal congruence to make each other’s behavior conform to expectations, which relies on informal and non-mandatory psychological contracts. Therefore, the formal contract of contractual governance and the psychological contract of relational governance can replace each other in reducing opportunistic behavior and thus promoting social responsibility.

Existing studies advocating that the two governance models may be understood as complementary highlight their differences in cost, mode, path, efficiency, and functions (Um & Oh, 2020; Zheng et al., 2008). We observed that, in terms of fostering social responsibility and the overall performance of the supply chain, the models are indeed complementary as they have unique functions that cannot be substituted for one another. For contractual governance, the legally binding formal contract increases the likelihood of conformity, becoming an important external driving force to promote the supply chain’s social responsibility. This explicit coercive effect is something that relational governance does not provide. Relational governance highlights training and guidelines from buyers to suppliers, feedback, two-way communication, and the trust between buyers and suppliers. The development of informal relationships helps suppliers improve capabilities and develop internal creativity to promote the supply chain’s social responsibility and improve its overall performance. Such internal driving force and creativity brought about by the development of these relationships do not occur in contractual governance. Therefore, contractual governance and relational governance have overlapping functional areas that can replace each other, and also have their own unique functions and effects on supply chain’s social responsibility and performance. Figure 3 shows this relationship.

Relationship between Contractual Governance and Relational Governance and Social Responsibility and Supplier Performance

Therefore, this study is consistent with the view that relational governance and contractual governance play both substitute and complementary roles (Sánchez et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2023). The findings of this study, starting from the models’ effectiveness in promoting supply chains’ social responsibility and overall performance, clarify that contractual governance and relational governance fulfill similar functions and can, therefore, replace one another, while also having unique and complementary roles, which renders both indispensable. This means that contractual governance and relational governance are not merely two sides of the same coin but represent distinct models.

For emerging markets, the threat of opportunistic behavior is even greater, which means a more substantial overlap between contractual governance and relational governance in reducing this behavior and uncertainties in SSCG in these markets compared to others. In the SSCG context, the difference in cost, benefit, and difficulty of governance models determines how the global supply chain chooses and weighs the models. Because the mandatory contract sums up the cost of prior contract negotiation, of supervision during the process, and the cost of possible default after the event, it brings great difficulties to SSCG. At the same time, due to the environment’s complexity and variability, many details cannot be included in the explicit provisions of the contract. We observed that the cost of supervision and implementation is high in contractual governance. However, relational governance, which is based on cultivating supplier capabilities, developing mutual consensus, strengthening communication, and forming trust, is important in making up for the above defects. However, it takes time for relationships to form and evolve. Therefore, from the analysis of the particularity of governance in emerging markets, due to the more complex and changing policies and cultural environment, as well as the obstacles brought by geographical distance and institutional differences with multinational suppliers, the cost of making formal contracts and the development of trust relations are both high but the effects are small. Thus, both of them should be developed in supply chain governance, especially in the early stages.

Contextual conditions required to select combinations of SSCG models

We discussed the relationship experience and trust level of both parties in the supply chain (Belhadi et al., 2021) and the complexity of the suppliers’ task and capability (Pfaff et al., 2023), considering the contexts analysis regarding the effects of contractual and relational governance on social responsibility (Soundararajan et al., 2021). This study constructs richer and more diversified GSCG conditions in emerging markets. Four variables stand out when it comes to affecting suppliers’ social responsibility, particularly in emerging markets. They are the suppliers’ internal driving forces, the external driving forces such as external government departments and thirdparty audit subjects, the goal congruence between buyers and suppliers, and the institutional distance of the countries where both parties are located. These conditions form a unified context that affects the buyer’s choice of governance model and the difference in the combination of contractual governance and relational governance rather than just considering the impact of a single condition. For example, two enterprises in India in the case study have strong capabilities, but due to the general relationship experience and large institutional distance, the buyer still chooses high contractual governance. This differs from previous studies’ conclusions that highly capable suppliers may necessarily lead buyers to choose relational governance (Klassen et al., 2023). A comprehensive examination of the multiple important factors of the SSCG model is necessary. In addition, existing studies have little analysis of the combination and effects of the two models of SSCG, although scholars have pointed out that the two governance models can jointly promote supply chain collaboration (Um & Oh, 2020), thus improving the governance effect (Poppo & Zenger, 2002). However, these authors ignore that the implementation of these two different governance models will have their own costs, such as contract formulation cost and relationship development cost, and there are great differences in the contexts and effects of relational governance and contractual governance. Existing studies lack an in-depth investigation into the circumstances and how to combine these two governance models effectively. Moreover, the changes in the choice of governance model brought about by various contexts have not been considered, and feasible solutions for actual governance are still absent. Our study finds that different combinations of relational and contractual governance may achieve the same effect on the effectiveness of social responsibility and performance. In the multiple case study, we found that the combinations of high relational and low contractual governance, balance between relational and contractual, and high contractual and low relational governance, may bring better supplier social responsibility and performance, but their selection and effects have different situational conditions. Among them, the supplier’s capability, the cooperation time and experience of buyers and suppliers and institutional distance, which including supplier’s own factors, the two sides’ factors, and the external environment factors, constitute the contexts of different governance model combinations.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Research conclusions

-

1. The relationship between the two global SSCG models is both substitutive and complementary, making them indispensable for social responsibility and supply chain performance. However, the main implementation strategies and internal logic of the two models differ. Relational governance and contractual governance have similar effects in promoting social responsibility, but their advantages and unique functions are complementary, with distinct internal modes of action. This study advances the current understanding of SSCG by clarifying the substitution and complementary roles of contractual and relational governance in promoting social responsibility and supply chain performance beyond the substitution vs. complementary debate. While prior research has debated whether these governance models act as substitutes (Cao & Lumineau, 2015; Huang et al., 2014) or adopt a complementary approach (Poppo & Zenger, 2002; Um & Oh, 2020), this work integrates both perspectives by delineating their functional overlaps and unique contributions: substitution reduces uncertainty and opportunism-formal contracts and psychological contracts serve similar functions albeit through different mechanisms. A complementary approach enhances both social responsibility and performance-contractual governance exerts external coercive pressure, while relational governance fosters internal motivation. This dual-role perspective aligns with Sánchez et al. (2012) and Wang et al. (2023), who argue that both models can coexist; however, this study further specifies when and how they substitute or complement each other. For emerging markets facing greater uncertainty and opportunistic risks, contractual and relational governance can achieve similar effects, the first through explicit provisions of formal contracts and the latter through psychological contracts developed by informal relationships. Social responsibility in the supply chain depends more on the cooperation of suppliers. From the perspective of the implementation of social responsibility practices, strategy and internal logic of contractual and relational governance, contractual governance is more of a one-way regulation and constraint on suppliers, where these practices are legally mandatory and executed as result of constraints and potential punishment for breaching the contract. In this case, the suppliers’ socially responsible behavior is passive and subjected to external pressure. For relational governance, the buyer may induce social responsibility through one-way capacity improvement, offering training, evaluation, and feedback to the supplier, and also through two-way interaction such as exchange, communication, and building trust. In relational governance, cultivation of capacity, cooperation, and participation in the process as well as the essential friendship and equivalence between the two sides are emphasized, enhancing the suppliers’ willingness and capability engage in social responsibility. Additionally, buyers’ external driving force promotes the suppliers’ internal creativity, which is more conducive to sustainable development from the perspective of results. As prior research often overlooks the unique challenges of emerging markets, where institutional voids, cultural distance, and policy instability amplify governance costs, our research also contextualizes governance in emerging markets. Due to elevated opportunism risks, the costs and benefits of using different governance models, unlike in stable markets, early-stage governance in emerging economies must combine both models to mitigate risks.

-

2. SSCG plays a role in the supply chain’s sustainable development and overall performance by influencing the suppliers’ social responsibility. Although a large number of empirical studies (Kuwornu et al., 2023; Zhang & Aramyan, 2009) have shown that contractual and relational governance impact the supply chain’s social responsibility and performance, there is no clear explanation of the internal relationship involving the characteristics of the governance models or their combination and the outputs in terms of social responsibility and performance. This study shows that contractual and relational governance can promote the suppliers’ social responsibilities regarding environmental protection, safety, human rights, and other aspects, as well as contribute to buyers’ sales performance. This increases their likelihood of receiving future orders, strengthens cooperation, and improves the satisfaction of their own employees, production efficiency, and product competitiveness, thus achieving the ultimate goal of sustainable supply chain development. In short, the two SSCG models impact social responsibility, and social responsibility practices influence suppliers’ performance, employee satisfaction and loyalty, product competitiveness, and sales.

-

3. Characteristics of suppliers, supply and demand parties, regulations, and cultural environment affect the influence of global SSCG in suppliers’ social responsibility in emerging markets, constituting a special role of GSCG in these markets. Current research starts from a single aspect, such as suppliers (Zhang, 2024), transactions (Um & Oh, 2020), or environmental (Soundararajan & Brown, 2016) characteristics, as contexts of SSCG. Our research highlights emerging market complexities and finds special contextual factors from multiple levels for SSCG. In SSCG, the suppliers’ internal driving forces, external driving forces such as pressure from government departments and third-party audit subjects, goal congruence between buyers and suppliers, and the institutional distance between buyers’ and suppliers’ home countries are important variables that affect the suppliers’ social responsibilities. The role of contractual and relational governance has to be integrated into the unique and significant situational factors in these emerging markets.

-

4. Due to the important roles of contractual and relational governance, previous research (e.g., Poppo & Zenger, 2002; Um & Oh, 2020) suggests that combining both governance models improves performance, but does not indicate how the two governance models should be combined and the conditions for effective combination. This study addresses this gap by showing that different governance combinations can achieve similar outcomes regarding the promotion of social responsibility, but depend on different contextual factors. Relational and contractual governance can interact in three combinations: high relational and low contractual governance, balanced relational and contractual governance, and high contractual and low relational governance. These combinations can bring similar governance effects, but each is suitable for different situational conditions. The conditions favoring each of the three combinations include the supplier’s capability, time cooperating and experience, goal congruence between buyers and suppliers, and their institutional distance. From the perspective of the role of different combinations, they all have similar positive effects. In the process of promoting supply chain social responsibility and sustainable development goals, there is no “one size fits all.” It is necessary to use relational and contractual governance according to different contexts to form a feasible combination of SSCG.

Managerial implications

-

1. GSCG, led by multinational enterprises, needs to make full use of contractual and relational governance. In regions with weak regulations (e.g., Southeast Asia, Africa), relying solely on contracts is ineffective due to high enforcement costs. Instead, firms should combine contracts with relational investments (e.g., joint sustainability programs, supplier audits with feedback loops). For buyers in supply chains, the comprehensive application of the two governance models can effectively reduce obstacles caused by national environmental differences and the asymmetry of rights and interests of all parties in the global supply chain, helping to promote its sustainable development and competitiveness. Considering the complex and diverse contexts of governance in emerging markets, neither the formal contracts nor the development of trust relationships are sufficient, and relational and contractual governance need to develop together to reduce uncertainty and opportunistic behavior.

-

2. GSCG, led by multinational enterprises, requires the willingness and capability to effectively promote suppliers to fulfill their social responsibilities. Especially for suppliers in emerging markets, effectively implementing environmental, human rights, safety, and other social responsibilities is a very difficult task. Buyers need to strengthen communication with suppliers, negotiate the difficulties caused by the differences in culture, laws, and regulations in the implementation of social responsibility, promote the consensus on cooperation, interests, and development of the two sides, and assist and guide suppliers to improve their capabilities, enhance their internal driving force, and develop social responsibility practices. This creates a virtuous cycle where ethical practices also drive business success, such as a fashion brand working closely with textile suppliers to improve water recycling processes, which not only reduces environmental harm but also cuts costs, benefiting both parties.

-

3. Leading enterprises in the global supply chain need to reasonably choose elements of the two governance models to achieve an effective combination. There are often multiple suppliers from different countries in the global supply chain, so it is necessary to choose a governance combination by considering institutional distance, cooperation time and experience, and the supplier’s capabilities. Given the complexity and variability of the emerging market environment, these contexts should be considered as a whole in supply chain governance, and the weight of relational and contractual governance should be reasonably selected. For maximum societal benefit, firms should assess whether suppliers are willing partners or need incentives, align governance with local regulations and global standards (e.g., UN SDGs), develop shared sustainability KPIs to ensure mutual commitment, and adapt governance models to local norms (e.g., relationship-heavy approaches in high-trust cultures like Japan vs. contract-heavy in litigious markets like Brazil). With the increase of cooperation time, the development of relationships and the establishment of trust should be enhanced, and social responsibility should be effectively promoted from the external responsibility of suppliers to the joint responsibility of both sides of the supply chain to increase sustainability.

-

Evaluated through a double-anonymized peer review.

-

The Peer Review Report is available at this link

-

FUNDING

This aiticle is funded by the China Association of Trade in Services(Project Number:FWMYKT-202428).

REFERENCES

-

Alexander, R. (2020). Emerging roles of lead buyer governance for sustainability across global production networks [J]. Journal of Business Ethics, 162(2), 269-290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04199-4

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04199-4 -

Belhadi, A., Kamble, S. S., Mani, V., Venkatesh, V. G., & Shi, Y. (2021). Behavioral mechanisms influencing sustainable supply chain governance decision-making from a dyadic buyer-supplier perspective [J]. International Journal of Production Economics, (236), 108136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108136

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108136 -

Boström, M., Jönsson, A. M., Lockie, S., Mol, A. P. J., & Oosterveer, P. (2015). Sustainable and responsible supply chain governance: Challenges and opportunities [J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 107, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.11.050

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.11.050 -

Cao, Z., & Lumineau, F. (2015). Revisiting the interplay between contractual and relational governance: A qualitative and meta-analytic investigation [J]. Journal of Operations Management, 33/34(1), 15-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.11.050

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.11.050 -

Dolci, P. C., Macada, A., & Paiva, E. L. (2017). Models for understanding the influence of Supply Chain Governance on Supply Chain Performance [J]. Supply Chain Management, (7), 424-441. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-07-2016-0260

» https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-07-2016-0260 -

Eisenhardt, K. M.(1989). Building Theories from Case Study Research [J]. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532-550.10.https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308385

» https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308385 -

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007).Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges [J]. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1),25-32.https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

» https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888 -

Feng, H., Nie, L., & Shi, Y.(2020).The Interaction between Supply Chain Governance Mechanisms and Supply Chain Performance: Based on the Mediating Effects of Information Sharing and the Moderating Effects of Information Technology Level [J]. Chinese management science, 28(2),104114.https://doi.org/10.16381/j.cnki.issn1003-207x.2020.02.011

» https://doi.org/10.16381/j.cnki.issn1003-207x.2020.02.011 -

Formentini, M., & Taticchi, P. (2016). Corporate sustainability approaches and governance mechanisms in sustainable supply chain management [J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 1920-1933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.12.072

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.12.072 - Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L.(1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research [M]: Aldine de Gruyter.

-

Huang, M.-C., Cheng, H.-L., & Tseng, C.-Y. (2014). Reexamining the direct and interactive effects of governance mechanisms upon buyer-supplier cooperative performance [J]. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(4), 704-716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2014.02.001

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2014.02.001 -

Huq, F. A., Chowdhury, I. N., & Klassen, R. D. (2016). Social management capabilities of multinational buying firms and their emerging market suppliers: An exploratory study of the clothing industry [J]. Journal of Operations Management, (46), 19-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2016.07.005

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2016.07.005 -

Jia, F., Zuluaga-Cardona, L., Bailey, A., & Rueda, X. (2018). Sustainable supply chain management in developing countries: An analysis of the literature [J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 189, 263-278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.248

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.248 -

Jia, Y., Wang, T., Xiao, K., & Guo, C. (2020). How to reduce opportunism through contractual governance in the crosscultural supply chain context [J]. Industrial Marketing Management, 91, 323337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.09.014

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.09.014 -

Klassen, R. D., Shafiq, A., & Fraser Johnson, P. (2023).Opportunism in supply chains: Dynamically building governance mechanisms to address sustainability-related challenges [J]. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review,171,103021.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2023.103021

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2023.103021 -

Kuwornu, J. K. M., Khaipetch, J., & Gunawan, E., et al.(2023). The adoption of sustainable supply chain management practices on performance and quality assurance of food companies [J]. Sustainable Futures, 5,100103.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sftr.2022.100103

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sftr.2022.100103 -

Pfaff, Y. M., Birkel, H., & Hartmann, E. (2023). Supply chain governance in the context of industry 4.0: Investigating implications of real-life implementations from a multi-tier perspective [J]. International Journal of Production Economics, 108862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2023.108862

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2023.108862 -

Pizzetti, M., Gatti, L., & Seele, P. (2021). Firms talk, suppliers walk: Analyzing the locus of greenwashing in the blame game and introducing ‘Vicarious Greenwashing’ [J]. Journal of Business Ethics, 170, 21-38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04406-2

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04406-2 -

Poppo, L., & Zenger, T.(2002). Do formal contracts and relational governance function as substitutes or complements? [J]. Strategic Management Journal, 23(8), 707-725.https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.249

» https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.249 -

Quarshie, A. M., Salmi, A., & Leuschner, R. (2016). Sustainability and corporate social responsibility in supply chains: The state of research in supply chain management and business ethics journals [J]. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 22(2), 82-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2015.11.001

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2015.11.001 -

Sánchez, J. M., Vélez, M. L., & Ramón-Jerónimo, M. A. (2012). Do suppliers’ formal controls damage distributors’ trust? [J]. Journal of Business Research, 65(7), 896-906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.06.002

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.06.002 -

Seuring, S., Aman, S., & Hettiarachchi, B. D., et al.(2022). Reflecting on theory development in sustainable supply chain management [J]. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain, 3, 100016.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clscn.2021.100016

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clscn.2021.100016 -

Sodhi, M. S., & Tang, C. S. (2018). Corporate social sustainability in supply chains: A thematic analysis of the literature [J]. International Journal of Production Research, 56(1/2), 882-901. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2017.1388934

» https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2017.1388934 -

Soundararajan, V., & Brown, J. A. (2016). Voluntary governance mechanisms in global supply chains: Beyond CSR to a stakeholder utility perspective [J]. Journal of Business Ethics, (134), 83-102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2418-y

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2418-y -

Soundararajan, V., Sahasranamam, S., Khan, Z., & Jain, T. (2021). Multinational enterprises and the governance of sustainability practices in emerging market supply chains: An agile governance perspective [J]. Journal of World Business, 56(2), 101149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2020.101149

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2020.101149 - Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990).Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques [M]: Sage Newbury Park CA

-

Um, K.-H., & Oh, J.-Y. (2020). The interplay of governance mechanisms in supply chain collaboration and performance in buyer-supplier dyads: Substitutes or complements [J]. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 40(4), 415-438. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-07-2019-0507

» https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-07-2019-0507 -

Wang, L., Jin, J. L., & Yang, D. (2023). The interplay of contracts and trust: Untangling betweenand within-dyad effects [J]. European Journal of Marketing, 57(2), 453-478. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM12-2021-0934

» https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM12-2021-0934 -

Yang, D., Sheng, S., Wu, S., & Zhou, K. Z. (2018). Suppressing partner opportunism in emerging markets [J]. Journal of Business Research, 90, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.04.037

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.04.037 -

Zhang, Q., Jin, J. L., & Yang, D. (2020). How to enhance supplier performance in China: Interplay of contracts, relational governance and legal development [J]. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 40(6), 777-808. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-02-2020-0093

» https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-02-2020-0093 -

Zhang, X., & Aramyan, L. H. A.(2009). conceptual framework for supply chain governance [J]. China Agricultural Economic Review, 1(2), 136-154.https://doi.org/10.1108/17561370910927408

» https://doi.org/10.1108/17561370910927408 -

Zhang, Y. (2024).The Moderating Role of Organizational Support on the Relationship between Green Supply Chain Practices, Governance and Sustainable Economic Performance: Evidence from China [J]. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 30(1),238-260.https://doi.org/10.3846/tede.2024.20138

» https://doi.org/10.3846/tede.2024.20138 -

Zheng, J., Roehrich, J. K., & Lewis, M. A.(2008).The dynamics of contractual and relational governance: Evidence from long-term public-private procurement arrangements [J]. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 14(1), 43-54.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2008.01.004

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2008.01.004

Edited by

-

Associate Editor:

Cyntia Meireles Martins

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

08 Sept 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

02 Oct 2024 -

Accepted

22 Apr 2025

GLOBAL SUSTAINABLE SUPPLY CHAIN GOVERNANCE, EFFECTIVENESS OF SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY, AND PERFORMANCE IN EMERGENT MARKETS: AN EXPLORATORY MULTIPLE CASE STUDY

GLOBAL SUSTAINABLE SUPPLY CHAIN GOVERNANCE, EFFECTIVENESS OF SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY, AND PERFORMANCE IN EMERGENT MARKETS: AN EXPLORATORY MULTIPLE CASE STUDY