ABSTRACT

Guava (Psidium guajava) can be parasitized by the plant-parasitic nematode Meloidogyne enterolobii, which causes a complex disease. Research on resistance involves studying infection, nematode multiplication in roots, and early symptom expression. This study aimed to confirm Meloidogyne enterolobii resistance in Psidium genotypes selected as potential guava rootstocks after their clonal propagation and determine the symptomatology associated with plant infection by evaluating leaf pigmentation indices and seedling growth rates. The experiment was conducted in a protected environment at the Research Support Unit of the State University of Northern Rio de Janeiro, in Campos dos Goytacazes, Rio de Janeiro state (RJ), between August 2023 and March 2024. A randomized block design was used, with seven treatments, 12 replicates, and one plant per plot. Seedlings, obtained through mini-cutting, were inoculated with 2,000 eggs and second-stage juveniles (J2) of M. enterolobii, and evaluated over 135 days. The resistance levels previously identified in seed-propagated seedlings were not consistently confirmed after vegetative propagation. Early parasitism symptoms coincided with changes in leaf pigment indices. The susceptibility of most genotypes, previously classified as resistant, suggests that epigenetic factors may influence the expression of resistance to M. enterolobii.

Key words:

root-knot nematode; rootstock; Psidium cattleianum; Psidium guajava; vegetative propagation

HIGHLIGHTS:

Propagation method and physiological conditions affect Psidium resistance to nematodes.

Leaf pigment indices are early indicators of nematode stress.

Chlorophyll and nitrogen balance index decline with increased nematode multiplication in the root environment.

RESUMO

A goiabeira (Psidium guajava) pode ser parasitada pelo fitonematoide Meloidogyne enterolobii, causando uma doença complexa. Estudos da resistência envolvem a infecção, multiplicação do nematoide nas raízes e expressão precoce de sintomas. Portanto, este estudo teve como objetivo reavaliar a resistência a M. enterolobii em genótipos de Psidium selecionados como potenciais porta-enxertos para goiabeira após propagação clonal e determinar a sintomatologia associada à infecção das plantas por meio de índices de pigmentação foliar e das taxas de crescimento de mudas. O experimento foi conduzido em ambiente protegido na Unidade de Apoio à Pesquisa da Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense, município de Campos dos Goytacazes-RJ, entre agosto de 2023 e março de 2024. Utilizou-se o delineamento em blocos casualizados, com sete tratamentos, com 12 repetições e uma planta por parcela. As mudas foram obtidas por miniestaquia, inoculadas com 2.000 ovos e J2 de M. enterolobii e avaliadas durante um período de 135 dias. Os níveis de resistência previamente encontrados em mudas de origem seminífera não foram todos confirmados após a propagação vegetativa. Sintomas precoces do parasitismo ocorreram juntamente com alterações nos índices de pigmentos foliares. A suscetibilidade da maioria dos genótipos, anteriormente classificados como resistentes, sugere que fatores epigenéticos atuem na expressão da resistência a M. enterolobii.

Palavras-chave:

nematoide das galhas; porta-enxerto; Psidium cattleianum; Psidium guajava; propagação vegetativa

Introduction

Guava (Psidium guajava L.) is a highly nutritious fruit commercially cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide (Das, 2020). It is consumed fresh and widely used in the food industry due to its rich nutritional profile (Singh et al., 2018).

Currently, the primary challenge in guava production in Brazil is guava decline, a plant health disorder caused by a complex interaction between the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne enterolobii and the fungus Neocosmospora falciformis. Parasitism by M. enterolobii alters root exudates, promoting microbial activity that compromises root physiology and weakens plant immunity against fungal infection, thereby accelerating plant deterioration (Souza et al., 2023).

Given the environmental toxicity, high cost, and limited effectiveness of currently available synthetic nematicides, developing integrated and sustainable management strategies is essential for effective control of plant-parasitic nematodes. One promising strategy is the development of M. enterolobii-resistant genotypes. Since no resistance has been reported in guava cultivars, research has focused on identifying resistance in other Psidium species, such as P. guineense (Souza et al., 2018) and P. cattleianum (Gomes et al., 2017). A hybrid between P. guajava and P. guineense was the first rootstock officially registered in Brazil for sustainable coexistence with nematodes (Souza et al., 2018), combining resistance with desirable fruit quality (Simões et al., 2023).

Genetic diversity in rootstocks is essential for boosting fruit yield and sustainability. However, nematode populations within the same genotype can be influenced by environmental factors, and resistance may vary due to its polygenic nature (Gomes et al., 2017). Consequently, resistance observed in a single juvenile plant might be affected after clonal propagation, due to epistatic interactions.

Monitoring physiological traits under nematode stress provides crucial insights into plant stress responses. Biotic stress conditions trigger physiological alterations in plants, often reflected in altered pigment levels, such as chlorophyll and anthocyanins (Baskar et al., 2018).

Studies show that Psidium species susceptible to M. enterolobii exhibit secondary symptoms, including leaf bronzing and post-inoculation chlorosis, attributed to root system damage and reduced water and nutrient uptake (Chiamolera et al., 2018). Similarly, Gomes et al. (2008) associated the onset of chlorosis and leaf wilting with nutritional deficiencies caused by nematode-induced physiological stress. A decline in chlorophyll indices indicates damage, given that these leaves would otherwise be at their peak assimilate production (Silva et al., 2016). In addition to evaluating plant survival and nematode reproduction, monitoring physiological traits under nematode stress provides valuable data on plant responses.

In this context, physiological indicators such as chlorophyll and anthocyanin content, along with pigment dynamics, can serve as early stress markers in plants and help elucidate the underlying mechanisms of nematode tolerance among different Psidium genotypes. Reduced chlorophyll content in guava plants under water deficit conditions (Roque et al., 2025) underscores the importance of pigment dynamics as early indicators of plant stress. Assessing these parameters alongside nematode reproduction provides a broader understanding of plant-nematode interactions and supports the selection of resilient genotypes for integrated management strategies.

Therefore, this study aimed to confirm M. enterolobii resistance in Psidium genotypes selected as potential rootstocks for guava after clonal propagation and determine the symptomatology associated with plant infection by evaluating leaf pigmentation indices and seedling growth rates.

Material and Methods

The experiment was conducted from August 2023 to March 2024 in the northern region of Rio de Janeiro state (RJ), Brazil (21° 45′ 44″ S, 41° 17′ 19″ W, altitude of 14 m). According to Köppen’s classification, the climate of the region is classified as Aw, tropical with a rainy summer, dry winter, and minimum monthly temperature above 18 °C.

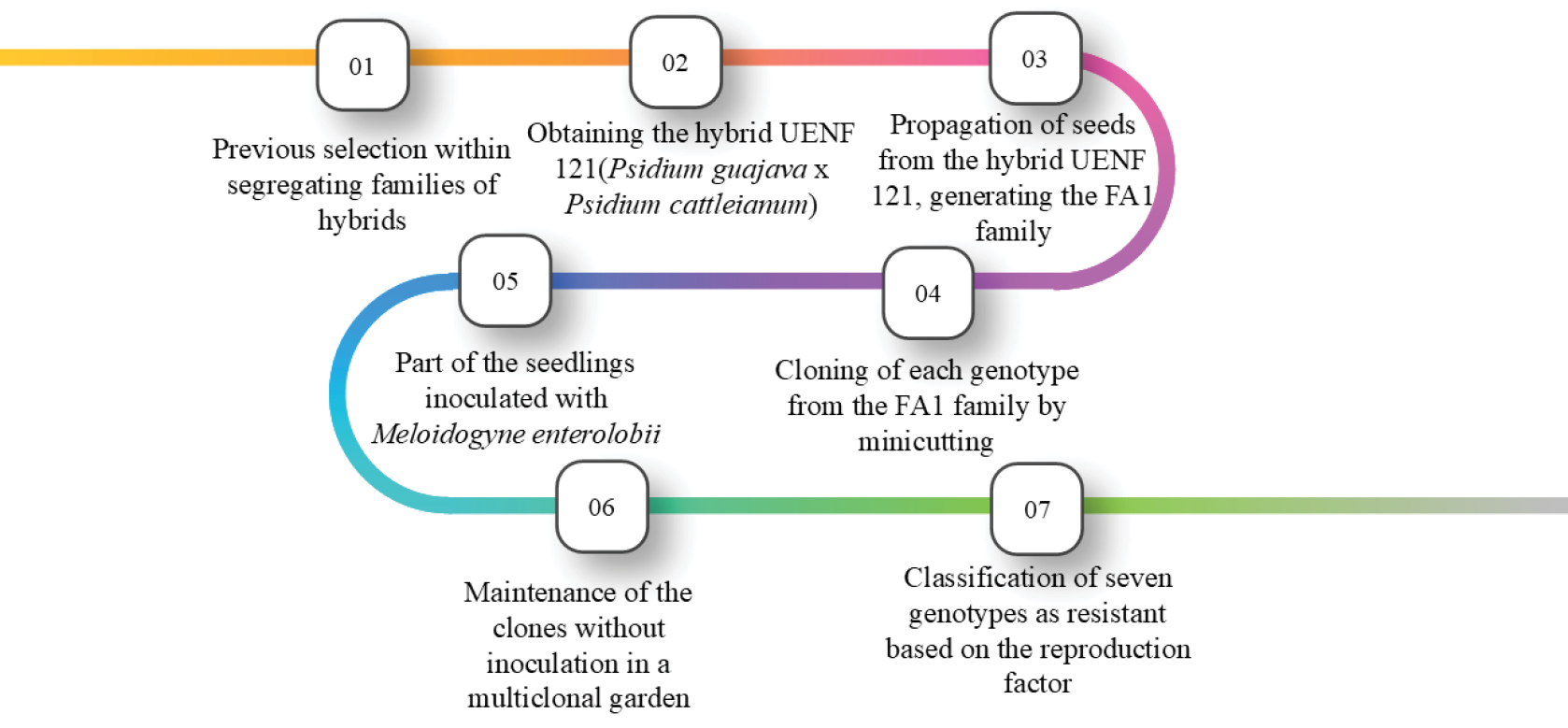

The genotypes evaluated in this study were derived from Galvão et al. (2024), and the selection process is summarized in Figure 1. Six genotypes with a reproduction factor lower than one were identified and selected for cloning using the mini-cutting technique (Arantes et al., 2021), along with the ‘Paluma’ guava cultivar, which served as the susceptible control. Each resistant plant was identified in an established clonal mini-garden and subsequently transplanted into 30-L pots maintained in a greenhouse (7.0 m wide, 20 m long, and 4.0 m high) without climate control, covered with 50% Sombrite® shade cloth and equipped with lateral mesh and a raffia-covered floor. The soil used in the pots was classified as Ultisol (Soil Survey Staff, 2022). Each pot was fertilized with 8.5 g L⁻¹ of limestone and 2.74 g L⁻¹ of single superphosphate. Additionally, a slow-release Osmocote® fertilizer (17-07-12 formulation) was added at a rate of 6.6 g L⁻¹. Irrigation was automated via a drip irrigation system, using two drippers per pot, each with a flow rate of 2.0 L h⁻¹. The irrigation schedule was adjusted based on the plants’ water requirements, which varied according to temperature. The genotypes remained under these conditions for approximately one year, after which their branches were pruned to stimulate the production of herbaceous shoots used for cuttings in the seedling production process, following the protocol described by Arantes et al. (2021).

Mini-cuttings were prepared with two pairs of leaves. The basal pair was removed, and the upper pair trimmed to half its original size. The cuttings were placed in 280 mL tubes filled with commercial Basaplant® substrate. They were subsequently maintained in a mist chamber for 60 days (15-second spraying intervals every 10 min, flow rate of 7 L h⁻¹, under a pressure of 4.0 kgf cm⁻², with one micro-sprinkler per m²).

After acclimatization, the plants were transplanted into 5 L pots filled with a 2:1:1 mixture of washed river sand, local soil (from the established clonal garden), and cattle manure. This mixture underwent a 72-hour solarization process to eliminate any pre-existing nematodes. After transplanting, the plants were placed on benches (1.15 m wide × 5 m long) 1 m above the ground in the greenhouse. The plants were irrigated via overhead micro-sprinklers at a density of 0.5 micro-sprinkler per m², with irrigation adjusted according to plant water requirements.

For this experiment, a randomized block design (RBD) was used. The experimental treatments consisted of six previously identified Psidium genotypes, along with the ‘Paluma’ cultivar, totaling seven treatments. Each treatment was replicated 12 times, with one plant per plot.

Throughout the experimental period, climate data were collected using a datalogger inside the greenhouse. The average conditions recorded were a maximum temperature of 36.3 °C, minimum temperature of 21.8 °C, maximum relative humidity of 92.0%, and minimum relative humidity of 53.8%. These values indicate an environment with consistently high temperatures and elevated humidity levels.

Inoculation with M. enterolobii was performed when the plants possessed three to five pairs of leaves (30 days after transplanting). A pure isolate maintained in tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum L.) was used as the inoculum source. To extract the inoculum, infected roots were processed using a modified Coolen & D’Herde (1972) extraction method, omitting the use of kaolin. The resulting nematode suspension was passed through stacked 65- and 500-mesh sieves and collected in a beaker. Under a stereoscopic microscope, using a Peters slide, the suspension was calibrated to a concentration of 2,000 M. enterolobii eggs + J₂ per 10 mL of water. Each seedling was inoculated with 10 mL of the suspension, which was distributed into four 1 cm-deep holes made in the soil around the plant collar.

Resistance was evaluated at 135 DAI (days after inoculation). The plants were removed from their pots and the shoot was separated from the root system. To extract eggs and second-stage juveniles (J2), the roots were processed using the same method previously described for obtaining the inoculum. The only modification was agitating the roots in a 6% aqueous solution of sodium hypochlorite (2% active chlorine), instead of using pure water. The egg and J₂ suspension obtained from each plant was homogenized, and three 1 mL aliquots were used for counting with a Peters slide, expressed as the final nematode population (FP).

The reproduction factor (RF) was calculated according to Oostenbrink (1966) by dividing the final population (number of eggs + J₂) by the initial inoculated population (eggs + J₂). RF = FP / 2000), where RF = 0 indicates immunity, RF < 1 resistance, and RF > 1 susceptibility (Oostenbrink, 1966).

The percentage reduction in RF (PRRF%) was also calculated. This was determined similarly to the RF FP/IP ratio (final population/initial population). The population with the highest reproduction index was considered the susceptibility reference. Next, the reference reproduction index was compared with that of the other populations, calculating the reduction percentage for each, following the methodology described by Moura & Régis (1987). Based on these values, the resistance levels of each Psidium genotype to M. enterolobii were defined as: HS - highly susceptible: PRRF% from 0 to 25%; S - susceptible: PRRF% from 26 to 50%; LR - low resistance: PRRF% from 51 to 75%; MR - moderately resistant: PRRF% from 76 to 95%; R - resistant: PRRF% from 96 to 99%; and HR - highly resistant/immune: PRRF% of 100%.

The ratio of the number of eggs + J₂ per gram of root (NOJ/G) was also calculated.

On the day of inoculation, SPAD index (leaf greenness index) readings were initiated using a portable chlorophyll meter (Minolta SPAD - 502 “Soil Plant Analyzer Development”, Japan) to indirectly and non-destructively measure total chlorophyll. Three consecutive readings were taken from the most recently matured leaf pair (the third pair from the apex) and the oldest leaf pair on each plant.

The nitrogen balance index (NBI) and relative chlorophyll (CHL), anthocyanin (ANTH), and flavonoid (FLV) contents were measured using a portable Dualex® meter (Scientific, FORCE-A model). Evaluations were conducted on the middle third of the last fully developed leaf at two time points: at inoculation (day 0), to evaluate plant status before pathogen development in the rhizosphere, and 135 days after M. enterolobii inoculation, selected as the optimal time point for assessing infestation severity. A different fully developed third leaf was sampled for each evaluation.

Biometric data, including plant height, stem diameter, and number of leaf pairs, were collected immediately after M. Enterolobii inoculation. Subsequent evaluations occurred at 0, 28, 55, 82, 109 and 135 days after inoculation (DAI), totaling six assessments, including the initial measurement (Sikandar et al., 2024).

Additional biometric data were obtained at 135 DAI, including: leaf area (cm²), measured with a LI-3100 LICOR bench-top meter (Lincoln, NE, USA); stem and leaf dry mass (g), determined after drying plant material in a forced-air oven at 70 °C for 72 hours, and shoot dry mass, measured using a precision balance. Fresh root system mass was also assessed with a precision balance, and root volume was determined by water displacement in a graduated cylinder after root system immersion.

All data underwent the Shapiro-Wilk normality test (5% probability). Non-normal data were transformed using Log (x + 1) before analysis of variance (ANOVA). Means were compared using Tukey’s test (5% probability), in R software with the ExpDes.pt package. Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted using Paleontological Statistics Software (PAST 4.03).

SPAD index and growth indices over time were analyzed using a split-plot design (genotypes as the main plot and evaluation times as subplots). Biometric evaluations conducted at multiple time points were also analyzed using a split-plot design in time. Data were subjected to regression analysis (5% probability), and means were compared using Tukey’s test (5% probability).

Results and Discussion

The Psidium genotypes tested for resistance to M. enterolobii exhibited significant variations in the number of eggs per gram of root, final nematode population, reproduction factor (RF), and RF reduction percentage (Table 1).

Genotype P22 stood out for exhibiting the lowest number of eggs per gram of root. However, its final population and RF did not differ significantly from those of other genotypes or from the ‘Paluma’ guava, the conventional susceptibility standard, except for P77 and P140, which had higher susceptibility indicators.

According to the nematode resistance classification established by Oostenbrink (1966), none of the analyzed genotypes achieved an RF of 0 or < 1, thus all were classified as susceptible. Under the classification based on the percentage reduction in the reproduction factor (PRRF%), established by Moura & Regis (1987), with genotype P140 serving as the susceptibility reference due to its highest reproduction factor, genotype P22 was classified as moderately resistant. The other genotypes were classified as susceptible, except for P77, which was classified as highly susceptible, and P90 and ‘Paluma’ as slightly resistant.

Ribeiro et al. (2019) classified thirty-four Psidium genotypes as resistant according to Oostenbrink (1966), while Moura & Regis (1987) identified forty-two resistant genotypes Similarly, Cavalcanti Júnior et al. (2021) found the same number of resistant genotypes using both classifications.

While resistance classification criteria are essential for grouping genotypes by their resistance levels, they should be used with caution. Depending on the infestation severity, genotypes with very similar nematode populations might be classified differently (e.g., one as resistant and another as susceptible with RF = 0.9 and 1.1, respectively). Likewise, genotypes with high nematode population growth may be deemed highly resistant when compared to those with very high populations. Therefore, when assessing resistance, the final population should always be considered first, and classification methods carefully assessed to determine the most suitable approach.

Studies such as that by Oliveira et al. (2019) highlight the importance of selecting robustly resistant genotypes, especially in regions where nematode infestation is common, given the significant damage caused by this disease. The high susceptibility observed in this study suggests that the evaluated genotypes would not be suitable as rootstocks in nematode-infested areas.

Additionally, it is important to note that genotypes previously classified as resistant at a certain developmental stage may exhibit changes in resistance depending on environmental conditions and management practices. Oliveira et al. (2019) emphasized that Psidium genotypes may not maintain consistent resistance under natural field infestation. In the present study, despite uniform inoculation pressure, the physiological age of the genotypes influenced their resistance patterns, underscoring the need to consider this factor in breeding programs for nematode resistance.

Silva et al. (2024) reported that, although vegetative propagation is generally expected to produce identical offspring, epigenetic changes can lead to a shift in susceptibility. These authors observed that epigenetic variations in the expression of the analyzed variables, including the reproduction factor, can alter nematode resistance. Jirtle & Skinner (2007) also emphasized that environmental factors, such as stress and nutrient availability, can induce epigenetic changes, which may alter a plant’s vulnerability to diseases.

The absence of resistance observed in this study may result from a complex interaction between genetic and epigenetic factors, influenced by the cloning process. Genotypes originally identified as resistant may lose resistance due to epigenetic reprogramming during vegetative development, as observed in guava accessions by Silva et al. (2024). According to Collett et al. (2023), M. enterolobii can complete its life cycle approximately 15 days after inoculation; thus, the 135-day period allowed for multiple reproductive cycles and a thorough assessment of plant response to nematode pressure.

An important factor to consider is that the plants evaluated in this study developed an adventitious root system originating from stem tissues or the base of mini-cuttings. By contrast, the genotypes previously classified as resistant were propagated via seeds and developed a taproot (axial) system, characterized by a dominant, deep-growing primary root. In the study by Oliveira et al. (2024), seed-propagated seedlings displayed underdeveloped root systems with low fresh mass at the time of evaluation, which may have limited nematode parasitism and reproduction due to root suberization. By contrast, all the clones obtained through vegetative propagation produced a larger number of adventitious roots, potentially facilitating parasitism and increasing nematode reproduction.

A previous study by Galvão et al. (2024) classified the samePsidiumgenotypes as resistant to M enterolobii. when evaluated as young plants with a taproot system. However, after a cycle of vegetative propagation via cuttings and development of an adventitious root system, their resistance classification changed. In the present study, these previously identified genotypes showed increased RF values, exceeding the threshold of 1.0. This change may be related to the loss of vigor and alterations in the typical root system architecture of seed-propagated plants, since adventitious roots often exhibit lower efficiency in nutrient and water uptake and may create a different chemical and structural environment for nematode development (Li, 2021). Additionally, physiological and epigenetic changes induced during clonal propagation processes may alter the plant’s defense mechanisms against biotic stress (Silva et al., 2024).

In summary, these results underscore the importance of carefully selecting Psidium genotypes for M. enterolobii management. The findings of this study highlight the need for thorough evaluation before planting in high-risk areas. Moreover, epigenetic variation during clonal propagation should be considered in future studies, since it may affect the stability of resistance traits.

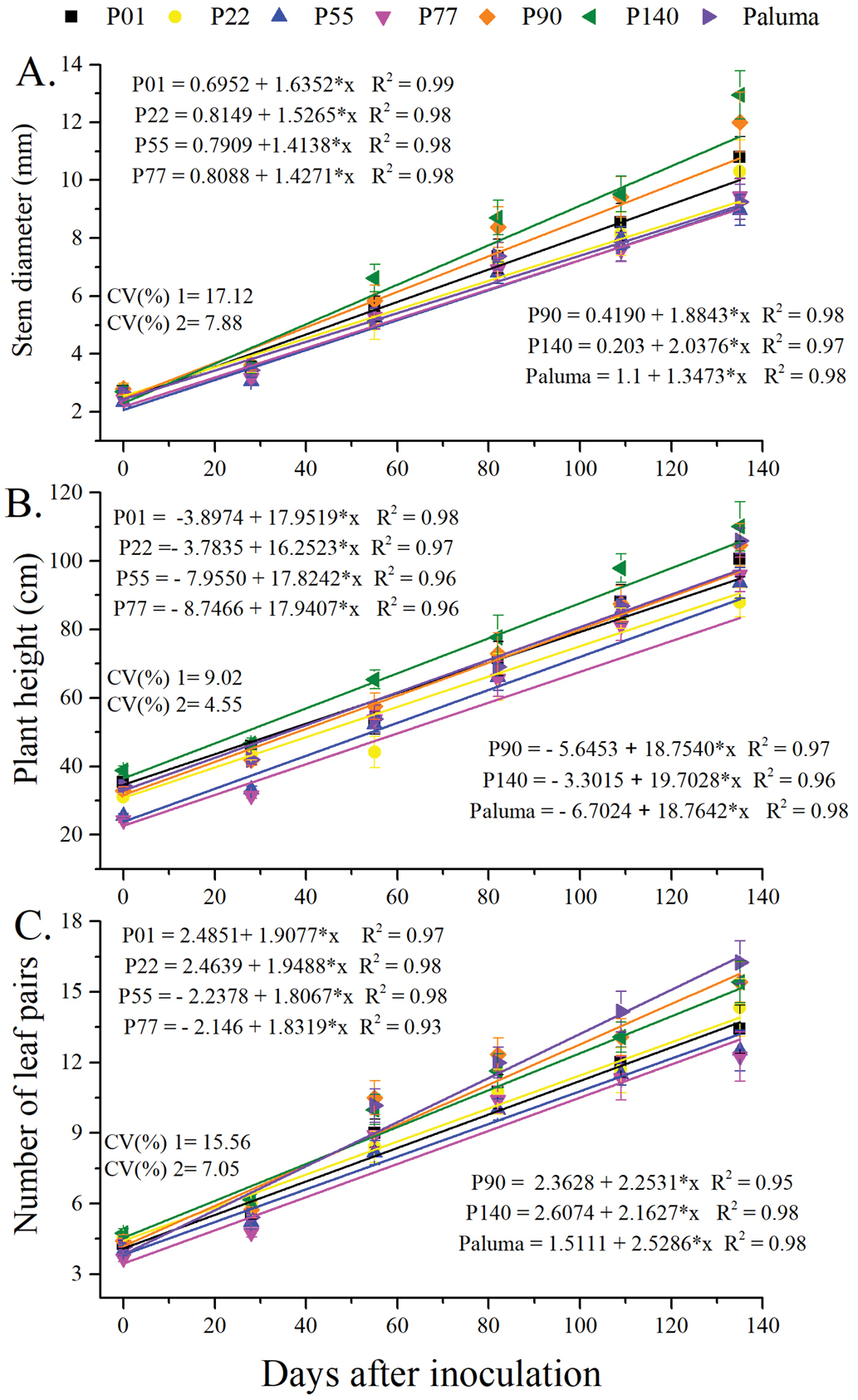

Analysis of variance revealed significant effects of evaluation periods and significant differences among genotypes. However, no significant genotype x evaluation period interaction was detected, indicating that although genotypes differed in growth rates, their response patterns over time remained consistent. A linear model appropriately described stem diameter growth of the different genotypes within the observed range (Figures 2A, B and C), with the slopes reflecting the varying growth rates.

Stem diameter (A), plant height (B) and number of leaf pairs (C) of Psidium genotypes over 135 days after inoculation (DAI) withMeloidogyne enterolobii

Genotypes P140 and P90 achieved the largest final stem diameter (Figure 2A). P140 also stood out in height, while P22 exhibited slower growth (Figure 2B). By contrast, the P55 guava tree had the highest number of leaf pairs (Figure 2C).

With respect to height growth, the growth curve of genotype P140 diverged from the other curves, reaching 110 cm at 135 DAI (Figure 2B). On the other hand, genotype P22 showed slower growth, but still reached an average height exceeding 87 cm at 135 DAI.

In relation to the number of leaf pairs, the ‘Paluma’ guava outperformed the other genotypes, particularly P55.

Overall, despite nematode parasitism, several evaluated genotypes displayed greater vigor than the ‘Paluma’ guava, particularly in stem diameter. This trait is crucial for rootstock selection, since increased vigor could shorten seedling production time (Mir et al., 2023). Combining vigor in the nursery with nematode resistance is a key goal for ensuring viable seedling production.

In terms of plant physiology, SPAD indices varied among genotypes, but a decreasing trend was observed over time in the newly mature leaves (Figure 3A).

SPAD indices measured in newly mature (A) and senescent leaves (B) of Psidium genotypes over 135 days after inoculation (DAI) withMeloidogyne enterolobii.

This reduction in SPAD index may be associated with nutritional deficiencies resulting from M. enterolobii infestation, which damages the root system through gall formation and reduces the functional root area (Collett et al., 2023). This damage impairs the translocation of key nutrients that act as cofactors in chlorophyll biosynthesis and maintenance (Hajihassani et al., 2013). The resulting nutrient deficiency limits chlorophyll production and accelerates leaf senescence, contributing to the decline in SPAD index and photosynthetic capacity. Additionally, nutrient imbalances can exacerbate oxidative stress in plant tissues, triggering the accumulation of secondary metabolites such as anthocyanins and flavonoids as protective responses (Leonetti & Molinari, 2020). The decrease in chlorophyll in newly matured leaves signals damage, given that these leaves are expected to exhibit peak assimilate production (Silva et al., 2016), while in senescent leaves, declining chlorophyll levels would be standard. Although nitrogen, a mobile nutrient in plants, is typically redistributed during senescence, this translocation may be slower under more favorable environmental conditions (Bieker & Zentgraf, 2013).

Overall, a decline in chlorophyll indices in senescent leaves (Figure 3B) was a common trend among the analyzed genotypes, but the intensity of this decline varied depending on genotype and stage of senescence. The quadratic pattern observed in most cases suggests an initial reduction in chlorophyll levels, followed by stabilization in the later evaluation periods (Figure 3B).

The decrease in chlorophyll content results from nematode-induced root system damage, hindering the plants’ ability to absorb essential nutrients required for maintaining green pigmentation (Hajihassani et al., 2013). The quadratic decline of SPAD indices in senescent leaves likely stems from an initial rapid chlorophyll degradation due to nutrient remobilization under nematode stress, followed by stabilization as the plant’s capacity to remobilize nutrients diminishes and leaf senescence progresses. Additionally, natural abscission and variations in the physiological state of sampled leaves over time contribute to fluctuations in SPAD values (Hajihassani et al., 2013; Taiz et al., 2015).

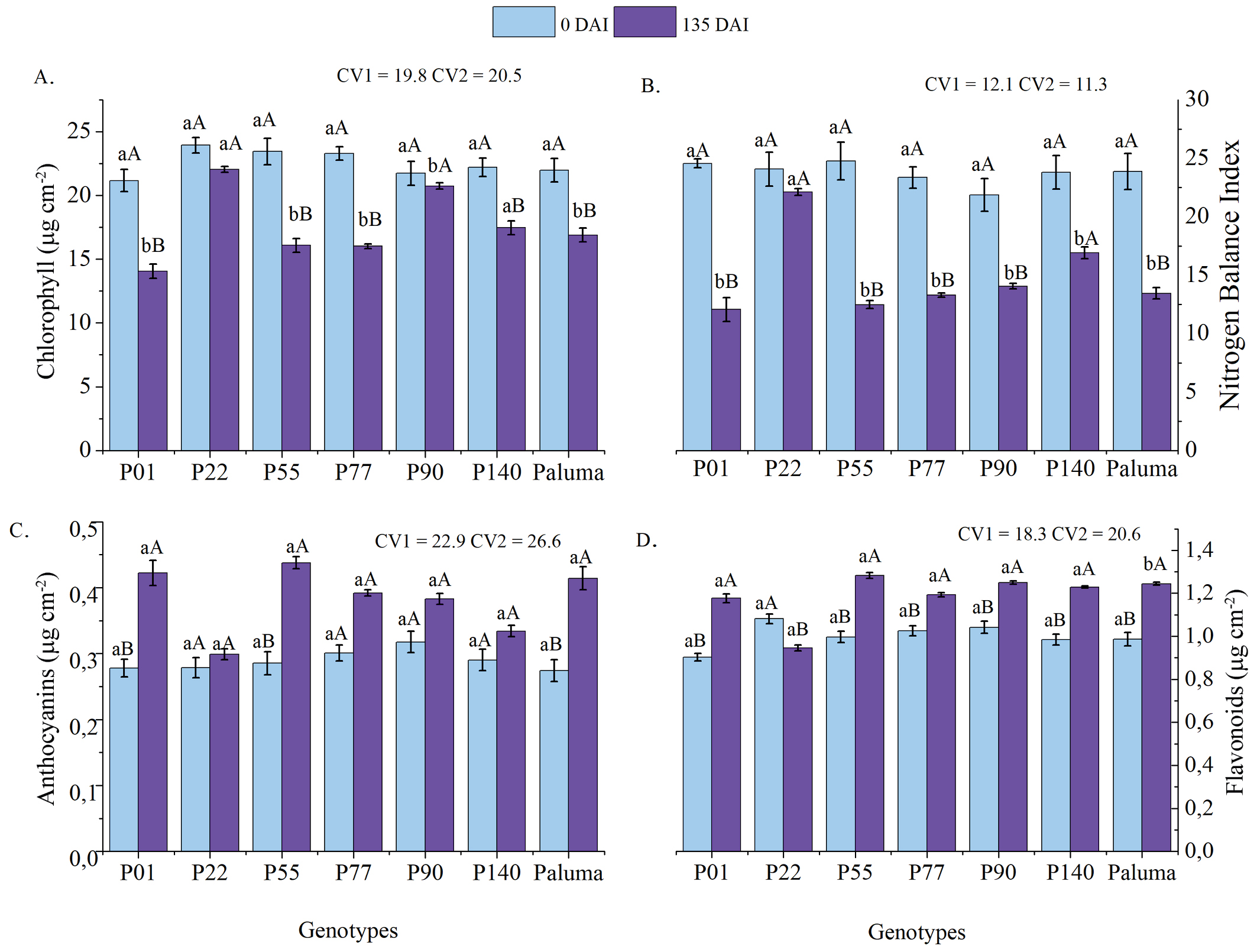

Figure 4 displays the combined indices of chlorophyll, flavonoids, anthocyanins, and nitrogen balance for all the genotypes at both 0 and 135 DAI. For most genotypes, chlorophyll indices (Figure 4A) were higher at 0 DAI, except for P22 and P90, which maintained high levels at both time points. The other genotypes, however, showed a sharp reduction in their chlorophyll index at 135 DAI.

Mean values of chlorophyll (A), nitrogen balance index - NBI (B), anthocyanins (C), and flavonoids (D) in guava genotypes (P01, P22, P55, P77, P90, P140, Paluma) at two different time points (0 DAI and 135 DAI)

With respect to the nitrogen balance index (NBI) (Figure 4B), a trend similar to that of chlorophyll was observed, with higher values at the initial time point and a significant decrease in the second. All genotypes, except for P22, exhibited a substantial reduction in NBI, suggesting a possible genotype x environment interaction and differing responses to biotic stress. The NBI, calculated as the ratio between chlorophyll and flavonoids, is an indicator of the plant’s nutritional status. Under conditions of low nitrogen (N) availability, plants allocate carbon to the synthesis of polyphenols, such as flavonoids (Cerovic et al., 2015). A decline in NBI reflects nitrogen deficiency, which compromises plant growth and development (Coelho et al., 2012).

Chlorophyll and NBI indices declined by an average of 21.9 and 37.3%, respectively, while anthocyanin (Figure 4C) and flavonoid (Figure 4D) levels increased by an average of 30.4 and 31.1% in the two evaluation periods, respectively. These changes help explain nematode proliferation in the root environment of the genotypes. However, genotype P22 exhibited a different profile, with significantly smaller reductions in chlorophyll (-7.9%) and NBI (-8.1%), along with smaller increases in antioxidant compounds (+7.4% for both anthocyanins and flavonoids). This reflects its lower parasitism levels and supports its classification as moderately resistant.

The physiological differences observed between the two time points also demonstrate the effect of parasitism on genotype performance. At the first time point (0 DAI), plants generally exhibited higher chlorophyll and NBI values, while at 135 DAI, these indices declined significantly. Flavonoids and anthocyanins increased, highlighting an adaptive stress response to nematode infection. These findings are important for identifying more stable genotypes better adapted to environmental variations, such as P22, which was less susceptible to temporal variations when compared to other genotypes.

The results become even more relevant when we consider that the genotypes were newly inoculated at the first time point, but had already undergone a period of M. enterolobii multiplication by the second. At the initial time point, higher levels of chlorophyll and NBI levels reflected the plants’ baseline physiological status, not yet significantly affected by nematode infestation. However, a sharp reduction in both chlorophyll and NBI was observed at the second evaluation point, indicating that the nematode might be impairing nutrient absorption and the plants’ photosynthetic capacity.

By 135 DAI, all genotypes exhibited the negative effect of M. enterolobii, which compromises the plant root system, hindering water and nutrient uptake, and consequently affecting their growth and development (Souza et al., 2023). On the other hand, the increase in flavonoid and anthocyanin levels at the second time point could be a direct response to nematode infestation stress. Plants might be activating defense mechanisms to mitigate the damage, given that these compounds are known for their protective role against environmental stresses, including pathogen parasitism (Baskar et al., 2018).

Photosynthetic pigment indices provide insights into photosynthetic efficiency and overall plant health (Agati et al., 2021). Hamdane et al. (2022) investigated the use of remote sensing, including flavonoid content and NBI, to evaluate stress in plants inoculated with M. incognita. Their findings indicated that plants with greater resistance to the nematode showed lower flavonoid concentrations and senescence indices, suggesting enhanced protection against pathogen-induced damage. Therefore, the reduction in chlorophyll and NBI levels, along with increasing flavonoid and anthocyanin concentrations, may reflect similar physiological defense mechanisms in response to M. eterolobii infection.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to investigate the relationships between M. enterolobii resistance traits and physiological indices, thereby enabling the identification and visualization of correlations among variables, simplifying the interpretation of interactions (Figure 5).

Principal component analysis (PCA), showing the distribution of seven Psidium genotypes based on the variables associated with resistance to M. enterolobii

The analysis reveals that the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) together explained 83.82% of the total data variability, with PC1 accounting for 60.68% and PC2 23.14%. PC1 was positively influenced by the variables FRM, FP, and RF, indicating a correlation among these variables. This component highlights the overall differences in nematode resistance among the genotypes. Genotypes located at the positive extremes of PC1 (such as P01, P77, and P140) exhibited higher values for these variables, reflecting lower resistance due to increased pathogen reproduction. On the other hand, CHL and NBI were oriented in the opposite direction, albeit at a low angle, suggesting a subtle negative correlation with PC1. This implies that as FRM, FP, and RF increase, CHl and NBI levels tend to decrease. Genotypes with higher nematode reproduction and root biomass showed lower levels of these indicators and more pronounced symptoms of infection.

PC2, in turn, was more strongly associated with CHL and NBI. Genotypes more displaced along the negative axis of PC2 (such as P22 and P90) appeared to be less impacted by these indices, possibly reflecting genotypes with greater resistance or a weaker physiological response to nematode-induced stress. Therefore, genotypes at the positive extremes of PC1 tend to exhibit greater susceptibility to the pathogen, while those more displaced along the negative axis of PC2 may reflect greater resistance or a weaker response to the evaluated traits, especially with respect to nematode reproduction.

PC1 clearly distinguishes between genotypes with different levels of nematode resistance. These findings corroborate those of recent studies, emphasizing the importance of variables such as FP, RF, and FRM in assessing resistance to nematode parasitism, where genotypes with a lower reproduction factor and less FRM exhibit greater resistance (Oliveira et al., 2024).

Table 2 shows that, at 135 DAI with M. enterolobii, the evaluated Psidium genotypes exhibited similar vegetative performance, suggesting that all were equally affected in their vegetative traits.

The vegetative similarity observed among the Psidium genotypes at 135 DAI indicates that all genotypes were significantly affected by M. enterolobii infection. High levels of root galling, egg masses, and nematode reproduction were recorded across all treatments, suggesting more susceptibility after vegetative propagation. This outcome may be associated with the aggressive parasitism typical of M. enterolobii, as reported by Oliveira et al. (2024) and Silva et al. (2024).

These findings align with those reported by Biazatti et al. (2016), who observed statistical differences in shoot and root system parameters among resistantPsidiumgenotypes but not among susceptible accessions. Furthermore, wildPsidiumspecies resistant toM. enterolobiitend to exhibit lower vegetative vigor, as demonstrated by Freitas et al. (2014).

Conclusions

-

The resistance level assessed in seedlings of seminal origin was not fully confirmed after vegetative propagation, given that most genotypes showed susceptibility to Meloidogyne enterolobii. However, genotype P22 maintained moderate resistance, with a 76% reduction in the reproduction factor. Early symptoms of parasitism were also expressed as changes in leaf pigment indices.

-

The physiological responses of the genotypes to M. enterolobii infestation confirmed the association between nematode parasitism and alterations in chlorophyll content, nitrogen balance, and antioxidant compound production. Among the evaluated genotypes, P22 exhibited greater physiological stability under infestation, thereby supporting its classification as moderately resistant.

-

The susceptibility of genotypes previously classified as resistant suggests a possible influence of epigenetic factors on the expression of resistance to M. enterolobii. Although the extent of this influence was not determined in this study, it may partially explain the variability observed after vegetative propagation. Further research is needed to elucidate the extent of this effect on nematode resistance in Psidium genotypes.

Literature Cited

-

Agati, G.; Guidi, L.; Landi, M.; Tattini, M. Anthocyanins in photoprotection: knowing the actors in play to solve this complex ecophysiological issue. The New Phytologist, v.232, e2228, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17648

» https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17648 -

Arantes, M. B. D. S.; Marinho, C. S.; Santos, R. F. D.; Galvão, S. P.; Vaz, G. P. Brassinosteroid accelerates the growth of Psidium hybrid during acclimatization of seedlings obtained from minicuttings. Pesquisa Agropecuária Tropical, v.50, e64743, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-40632020v5064743

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-40632020v5064743 - Baskar, V.; Venkatesh, R.; Ramalingam, S. Flavonoids (antioxidants systems) in higher plants and their response to stresses. In: Gupta, D. K.; Palma, J. M.; Corpas, F. J. (eds.). Antioxidants and antioxidant enzymes in higher plants. Singapore: Springer, 2018. Cap. 12, p.253-268.

-

Biazatti, M. A.; Souza, R. M.; Marinho, C. S.; Guilherme, D. O.; Campos, G. S.; Gomes, V. M.; Bremenkamp, C. A. Resistência de genótipos de araçazeiros a Meloidogyne enterolobii Ciência Rural, v.46, p.418-420, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-8478cr20150323

» https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-8478cr20150323 -

Bieker, S.; Zentgraf, U. Plant senescence and nitrogen mobilization and signaling. Senescence and Senescence-Related Disorders, v.104, p.53-83, 2013. https://doi.org/10.5772/54392

» https://doi.org/10.5772/54392 -

Cavalcanti Júnior, E. D. A.; Moraes Filho, R. M. D.; Rossiter, J. G. D. A.; Montarroyos, A. V. V.; Musser, R. D. S.; Martins, L. S. S. Reação de genótipos do gênero Psidium spp. a Meloidogyne enterolobii Summa Phytopathologica, v.46, p.333-339, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-5405/193123

» https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-5405/193123 - Cerovic, Z. G.; Ghozlen, N. B.; Milhade, C.; Obert, M.; Debuisson, S.; Moigne, M. L. Nondestructive diagnostic test for nitrogen nutrition of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) based on Dualex leaf-clip measurements in the field. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, v.63, p.3669-3680, 2015.

-

Chiamolera, F. M.; Martins, A. B. G.; Soares, P. L. M.; Cunha-Chiamolera, T. P. L. D. Reaction of potential guava rootstocks toMeloidogyne enterolobii Revista Ceres, v.65, p.291-295, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-737X201865030010

» https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-737X201865030010 -

Coelho, F. S.; Fontes, P. C. R.; Finger, F. L.; Cecon, P. R. Avaliação do estado nutricional do nitrogênio em batateira por meio de polifenóis e clorofila na folha. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira, v.47, p.584-592, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-204X2012000400015

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-204X2012000400015 -

Collett, R. L.; Rashidifard, M.; Marais, M.; Fourie, H. Insights into the life-cycle development of Meloidogyne enterolobii, M. incognita and M. javanica on tomato, soybean and maize. European Journal of Plant Pathology, v.168, p.137-146, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-023-02741-9

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-023-02741-9 - Coolen, W. A.; D’herde, C. J. A method for the quantitative extraction of nematodes from plant tissue. Ghent: State Nematology and Entomology Research Station, 1972. 77p.

-

Das, H. Review on crop regulation and cropping techniques on guava. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences, v.9, p.1221-1226, 2020. https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2020.912.144

» https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2020.912.144 -

Freitas, V. M.; Correa, V. R.; Motta, F. C.; Sousa, M. G.; Gomes, A. C. M. M.; Carneiro, M. D. G.; Carneiro, R. M. D. G. Resistant accessions of wild Psidium spp. to Meloidogyne enterolobii and histological characterization of resistance. Plant Pathology, v.63, p.738-746, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12149

» https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12149 -

Galvão, S. P.; Marinho, C. S.; Santos, R. F.; Vieira Júnior, J. O. L.; Viana, A. P.; Souza, R. M. Simultaneous cloning and selection of Psidium genotypes resistant to Meloidogyne enterolobii Semina: Ciências Agrárias, v.45, p.1215-1226, 2024. https://doi.org/10.5433/1679-0359.2024v45n4p12

» https://doi.org/10.5433/1679-0359.2024v45n4p12 -

Gomes, V. M.; Ribeiro, R. M.; Viana, A. P.; Souza, R. M.; Santos, E. A.; Rodrigues, D. L.; Almeida, O. F. Inheritance of resistance to Meloidogyne enterolobii and individual selection in segregating populations of Psidium spp. European Journal of Plant Pathology , v.148, p.699-708, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-016-1126-5

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-016-1126-5 - Gomes, V. M.; Souza, R. M.; Silva, M. M.; Dolinski, C. Caracterização do estado nutricional de goiabeiras em declínio parasitadas porMeloidogyne mayaguensis Nematologia Brasileira, v.32, p.154-160, 2008.

-

Hajihassani, A.; Smiley, R. W.; Afshar, F. J. Effects of co-inoculation with Pratylenchus thornei and Fusarium culmorum on growth and yield of winter wheat. Plant Disease, v.97, p.1470-1477, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-02-13-0168-RE

» https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-02-13-0168-RE -

Hamdane, Y.; Gracia-Romero, A.; Buchaillot, M. L.; Sanchez-Bragado, R.; Fullana, A. M.; Sorribas, F. J.; Kefauver, S. C. Comparison of proximal remote sensing devices of vegetable crops to determine the role of grafting in plant resistance to Meloidogyne incognita Agronomy, v.12, e1098, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12051098

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12051098 -

Jirtle, R. L.; Skinner, M. K. Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nature Reviews Genetics, v.8, p.253-262, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2045

» https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2045 -

Leonetti, P.; Molinari, S. Epigenetic and metabolic changes in root-knot nematode-plant interactions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, v.21, e7759, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21207759

» https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21207759 -

Li, S. W. Molecular bases for the regulation of adventitious root generation in plants. Frontiers in Plant Science, v.12, e614072, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.614072

» https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.614072 - Mir, M. M.; Parveze, M. U.; Iqbal, U.; Rehman, M. U.; Kumar, A.; Simnani, S. A.; Ganai, N. A.; Mehdi, Z.; Nazir, N.; Khalil, A.; Rather, B. A.; Bhat, Z. A.; Bhat, M. A. Development and selection of rootstocks. In: Mir, M. M.; Rehman, M. U.; Iqbal, U.; Mir, S. A. (eds.). Temperate nuts. Singapore: Springer , 2023. Chap. 3, p. 45-78.

- Moura, R. M.; Regis, E. M. O. Reações de feijoeiro comum (Phaseolus vulgaris) em relação ao parasitismo de Meloidogyne javanica e M. incognita (Nematoda: Heteroderidae). Nematologia Brasileira , v.11, p.215-225, 1987.

-

Oliveira, P. G. D.; Queiróz, M. A. D.; Castro, J.; Ribeiro, J.; Oliveira, R. S. D.; Silva, M. J. L. D. Reaction of Psidium spp. accessions to different levels of inoculation with Meloidogyne enterolobii Revista Caatinga, v.32, p.419-428, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-21252019v32n212rc

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-21252019v32n212rc -

Oliveira, P. G. D.; Queiroz, M. A. D.; Castro, J. M. D. C. E.; Silva, M. M. D. Resistance of guava accessions to Meloidogyne enterolobii Revista Caatinga , v.37, e11485, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-21252024v37n11485

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-21252024v37n11485 - Oostenbrink, M. Major characteristic of the relation between nematodes and plants. Wageningen: Medelingen Landbowhoge School. 1966. p.8-14

-

Ribeiro, R. M.; Gomes, V. M.; Viana, A. P.; Souza, R. M. D.; Santos, P. R. D. Selection of interspecific Psidium spp. hybrids resistant to Meloidogyne enterolobii Acta Scientiarum Agronomy, v.41, p.1-11, 2019. https://doi.org/10.4025/actasciagron.v41i1.42702

» https://doi.org/10.4025/actasciagron.v41i1.42702 -

Roque, I. A.; Soares, L. A. dos. A.; Lima, V. L. A. de; Sousa, V. F. D. O.; Lima, G. S. de; Gheyi, H. R.; Silva, S. T. D. A. Foliar application of salicylic acid mitigates water deficit in guava. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, v.29, e288437, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v29n5e288437

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v29n5e288437 -

Sikandar, A.; Wu, F.; He, H.; Ullah, R. M. K.; Wu, H. Growth, physiological, and biochemical variations in tomatoes after infection with different density levels of Meloidogyne enterolobii Plants, v.13, e293, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13020293

» https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13020293 -

Silva, A. R. A.; Bezerra, F. M. L.; Lacerda, C. F. de; Sousa, C. H. C. de; Chagas, K. L. Pigmentos fotossintéticos e potencial hídrico foliar em plantas jovens de coqueiro sob estresses hídrico e salino. Revista Agro@mbiente On-line, v.10, p.317-325, 2016. https://doi.org/10.18227/1982-8470ragro.v10i4.3650

» https://doi.org/10.18227/1982-8470ragro.v10i4.3650 -

Silva, M. M. P. D.; Queiróz, M. A. D.; Coutinho, M. D. S.; Oliveira, P. G. D. Preservation of moderately resistant or tolerant genotypes: a strategy to overcome guava decline. Ciência Rural , v.54, e20220500, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-8478cr20220500

» https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-8478cr20220500 -

Simões, W. L.; Andrade, V. P. D.; Silva, J. S. D.; Santos, C. A.; Sousa, J. S. D.; Calgaro, M.; Nascimento, B. R. D. Fruit production and quality of ‘Paluma’ guava with nematode-tolerant rootstock irrigated in the semi-arid region. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental , v.27, p.400-406, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v27n5p400-406

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v27n5p400-406 -

Singh, N.; Sharma, D. P.; Kumari, S.; Kalsi, K. Techniques for crop regulation in guava-a review. International Journal of Farm Sciences, v.8, p.131-135, 2018. https://doi.org/10.5958/2250-0499.2018.00068.X

» https://doi.org/10.5958/2250-0499.2018.00068.X -

Soil Survey Staff. Keys to soil taxonomy. 13.ed. USDA - Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2022. 401p. Available at: Available at: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-09/Keys-to-SoilTaxonomy.pdf Accessed on: May 10, 2025.

» https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-09/Keys-to-SoilTaxonomy.pdf -

Souza, R. M.; Oliveira, D. F.; Gomes, V. M.; Viana, A. J.; Silva, G. H.; Machado, A. R. Meloidogyne enterolobii-induced changes in guava root exudates are associated with root rotting caused by Neocosmospora falciformis Journal of Nematology, v.55, e20230055, 2023. https://doi.org/10.2478/jofnem-2023-0055

» https://doi.org/10.2478/jofnem-2023-0055 -

Souza, R. R. C. de; Santos, C. A. F.; Costa, S. R. da. Field resistance to Meloidogyne enterolobii in a Psidium guajava × P. guineense hybrid and its compatibility as guava rootstock. Fruits, v.73, p.118-124, 2018. https://doi.org.10.17660/th2018/73.2.4

» https://doi.org.10.17660/th2018/73.2.4 - Taiz, L.; Zeiger, E.; Møller, I. M.; Murphy, A. Plant physiology and development. 6 ed. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates, 2015. 761p.

Funding statement

Data availability

No supplementary materials were included in this study.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

01 Sept 2025 -

Date of issue

Dec 2025

History

-

Received

02 Mar 2025 -

Accepted

20 June 2025 -

Published

08 July 2025

Changes in root environment affect Meloidogyne enterolobii resistance and pigment synthesis in Psidium

Changes in root environment affect Meloidogyne enterolobii resistance and pigment synthesis in Psidium

The vertical bars represent the standard error (n = x); * p ≤ 0.05 (F test); CV1 - Coefficient of variation among genotypes (main factor). CV2 - Coefficient of variation within time (subplots)

The vertical bars represent the standard error (n = x); * p ≤ 0.05 (F test); CV1 - Coefficient of variation among genotypes (main factor). CV2 - Coefficient of variation within time (subplots)

The vertical bars represent the standard error (n = x); * p ≤ 0.05 (F test); CV1 - Coefficient of variation among genotypes (main factor). CV2 - Coefficient of variation within time (subplots).

The vertical bars represent the standard error (n = x); * p ≤ 0.05 (F test); CV1 - Coefficient of variation among genotypes (main factor). CV2 - Coefficient of variation within time (subplots).

The vertical bars represent the standard error (n = x); Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between genotypes at each time point, while different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between time points for the same genotype, according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05); CV1 - Coefficient of variation among genotypes (main factor). CV2 - Coefficient of variation within time (subplots). DAI - days after inoculation

The vertical bars represent the standard error (n = x); Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between genotypes at each time point, while different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between time points for the same genotype, according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05); CV1 - Coefficient of variation among genotypes (main factor). CV2 - Coefficient of variation within time (subplots). DAI - days after inoculation

RFM - Root fresh mass, CHL - Chlorophyll, NBI - Nitrogen balance index, FP - Final population, RF - Reproduction factor

RFM - Root fresh mass, CHL - Chlorophyll, NBI - Nitrogen balance index, FP - Final population, RF - Reproduction factor