ABSTRACT

The salinity of irrigation water impairs crops’ photosynthesis, growth, and development. Among the crops sensitive to salinity, red rice is one of the most affected. Methyl jasmonate (MeJa) is a plant signaling molecule widely recognized for its defense against abiotic stresses. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of exogenous application of MeJa on the morphophysiological aspects of red rice under salt stress. The experiment was conducted in randomized blocks, in a 3 × 3 factorial scheme, with three levels of salinity of the irrigation water (0.5, 3.5, and 6.5 dS m-1) and three concentrations of methyl jasmonate (0, 250, and 500 μM). The application of MeJa at concentrations of 250 and 500 μM showed promise in mitigating the adverse effects of moderate salt stress (3.5 dS m-1). However, it was not sufficient to completely reverse the damage caused by the more severe salinity level (6.5 dS m-1). MeJa concentration of 250 μM was most effective at the salinity level of 3.5 dS m-1, demonstrating a positive impact on root length and volume, gas exchange, and chlorophyll.

Key words:

Oryza sativa L.; abiotic stress; phytohormones; salinity

HIGHLIGHTS:

Methyl jasmonate (MeJa) increased plant height and CO2 assimilation rate in red rice under water salinity of 3.5 dS m-1.

Salinity of 3.5 dS m-1 reduced gas exchange, but MeJa partially mitigated these impacts at 250 µM under this salinity level.

MeJa at 250 µM improved plant growth and CO2 assimilation under water salinity of 3.5 dS m-1.

RESUMO

A salinidade da água de irrigação prejudica a fotossíntese, o crescimento e o desenvolvimento das culturas agrícolas. Entre as culturas sensíveis à salinidade, o arroz vermelho é uma das mais afetadas. O metil jasmonato (MeJa) é uma molécula sinalizadora vegetal amplamente reconhecida por sua atuação na defesa contra estresses abióticos. Diante disso, o objetivo deste estudo foi avaliar a aplicação exógena de MeJa nos aspectos morfofisiológicos do arroz vermelho sob estresse salino. O experimento foi conduzido em blocos casualizados, em esquema fatorial 3 × 3, com três níveis de salinidade da água de irrigação (0,5; 3,5 e 6,5 dS m-1) e três concentrações de metil jasmonato (0; 250 e 500 μM). A aplicação de MeJa nas concentrações de 250 e 500 μM mostrou-se promissora na mitigação dos efeitos adversos do estresse salino moderado (3,5 dS m-1). No entanto, não foi suficiente para reverter completamente os danos causados pelo nível de salinidade de água mais severo (6,5 dS m-1). A concentração de 250 μM de MeJa foi a mais eficaz no nível salino de 3,5 dS m-1, demonstrando impacto positivo nas características de comprimento e volume de raiz, troca gasosa e clorofila.

Palavras-chave:

Oryza sativa L.; estresse abiótico; fitormônios; salinidade

Introduction

Plants are often exposed to abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, and extreme temperatures, exacerbated by climate change. Global temperatures and climate change directly contribute to the increase of salinity in agricultural soils (Wang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021). Salinity affects photosynthesis, reducing chlorophyll and carotenoids, and impairs the structure of chloroplasts, photosystem II, transpiration, and gas exchange (Silva et al., 2024). In addition, it causes osmotic and oxidative stresses, inhibiting germination, vegetative growth, and reproductive development, which reduces crop yields (Fu et al., 2021).

Among the most salinity-sensitive crops, rice (Oryza sativa L.) stands out, especially in the early stages of development, such as the seedling phase and vegetative growth (Zhang et al., 2021). High salinity alters plant metabolism, compromising water and nutrient uptake and resulting in reduced growth and lower yield, even at salinity level of 3 dS m-1 (Haque et al., 2021; Hussain et al., 2022). Red rice has gained interest in its nutritional and medicinal properties among rice varieties, attributed to macronutrients and bioactive compounds such as sterols, vitamins, and phenolic compounds (Baptista et al., 2024). In addition to its antioxidant action, red rice stands out for its high zinc content, which is essential for strengthening the immune system and for wound healing. It is also a significant source of vitamin B6, which contributes to regulating LDL cholesterol levels and maintaining cardiovascular health (Maibangsa et al., 2023).

To mitigate the effects of salt stress, substances with attenuation properties, such as phytohormones, are used. These natural and non-toxic compounds regulate essential physiological processes, including growth, development, and stress response, promoting environmental signal detection and transmission adaptations (Ku et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2024). Methyl jasmonate (MeJa), a widely recognized phytohormone, acts in defense against herbivores and adaptation to abiotic stresses, including salt stress (Ahmadi et al., 2018; Hussain et al., 2022; Zhou & Jander, 2022; Lopes et al., 2024). Methyl jasmonate regulates physiological and biochemical processes such as antioxidant responses, osmotic adjustments, and photoprotection, helping to mitigate stress damage and maintain plant growth and photosynthetic efficiency (Ahmadi et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020).

Exogenous application of MeJa in red rice can attenuate the negative impacts of salt stress, promoting improvements in morphophysiological aspects, such as growth, photosynthetic efficiency, and antioxidant mechanisms (Peethambaran et al., 2018; Hussain et al., 2022). Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of exogenous application of methyl jasmonate on the morphophysiological aspects of red rice under salt stress.

Material and Methods

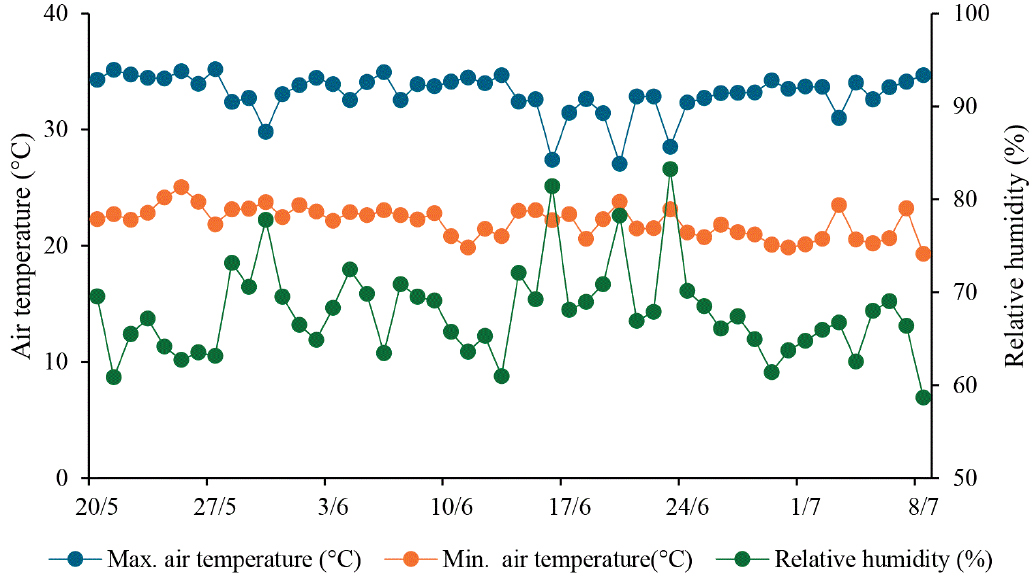

The study was carried out in a greenhouse located in the Didactic Garden of the Federal Rural University of the Semi-Arid Region (5° 12′ 28” S, 37° 19′ 04” W, altitude of 24 m), in Mossoró, RN, Brazil, from May to July 2024. The region has a BSh-type climate, with a very hot dry season and summer rains (Alvares et al., 2013). Daily air temperature and relative humidity data were collected during the experiment using a digital thermo-hygrometer (Figure 1).

The red rice cultivar used was MNA RN 0802, characterized by cateto grains, a biological cycle of 104 to 122 days, modern plant architecture and high susceptibility to lodging (Pereira et al., 2014). The seeds were sown in polyethylene pots with a capacity of 9 dm³, filled with soil collected from the Didactic Garden, with five seeds sown per pot at a depth of 3 cm. At 12 days after sowing (DAS), thinning was done, keeping only one plant per pot. The soil used was Ultisol (United States, 2014), classified as Argissolo Vermelho-Amarelo in the Brazilian Soil Classification System (Santos et al., 2018), whose characterization is presented in Table 1.

The experiment was carried out in a randomized block design, in a 3 × 3 factorial scheme, with four replications, totaling 36 experimental units in which three plants per pot were maintained. The treatments consisted of three levels of electrical conductivity of the irrigation water [ECw: 0.5, 3.5 and 6.5 dS m-1 based on the study of Rachmawati et al. (2020)], corresponding to the levels of salt stress (no stress, moderate stress and severe stress), and three concentrations of methyl jasmonate (MeJa): 0, 250 and 500 μM based on the study of Henschel et al. (2023).

Salt concentrations were applied from the emergence of the third leaf of red rice (15 DAS), with daily irrigation maintaining the field capacity at 80% (Girardi et al., 2016). The saline waters were stored in plastic containers with a capacity of 60 dm³. Manual weeding was carried out whenever necessary to control weeds during the experiment.

The application of methyl jasmonate (MeJa) began on the first day of irrigation with saline water (15 DAS). MeJa concentrations were prepared using distilled water and a Tween 80 (0.05%) adhesive spreader to improve plant absorption. The applications were carried out by foliar spraying, using a manual sprayer, every seven days, totaling five applications. The volume of solution used per plant at each application was 18 mL.

The chlorophyll and chlorophyll a fluorescence indices were evaluated at 52 DAS. Chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, chlorophyll total and chlorophyll a/chlorophyll b ratio were analyzed using a portable digital chlorophyll meter (Clorofilog, model CFL-1030, FALKER), and the results were expressed as FCI (Falker Chlorophyll Index). In addition, the initial fluorescence (F0), maximum fluorescence (Fm), variable fluorescence (Fv), and maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm) were analyzed using a portable digital fluorometer (OS-30p, Opti-sciences), in which the leaves were kept in the dark for 30 minutes with the aid of leaf clips.

Gas exchange was evaluated at 52 DAS using a portable infrared gas analyzer (GFS-3000, Walz). Net CO2 assimilation rate (A) (μmol CO2 m⁻² s-1), stomatal conductance (gs) (mol H2O m⁻² s-1), transpiration (E) (mmol H2O m⁻² s-1), internal CO2 concentration (Ci) (μmol CO2 mol-1), and vapor pressure deficit (VPD) (kPa) were evaluated. Next, instantaneous water use efficiency (WUE = A/E), intrinsic water use efficiency (iWUE = A/gs), and instantaneous carboxylation efficiency (iCE = A/Ci) were calculated. It was not possible to obtain results for these variables at the salinity level of 6.5 dS m-1 at both MeJa concentrations due to the damage caused by severe salt stress.

For the variables relative water content (RWC) (Irigoyen et al., 1992), leaf moisture (LM) (Slavick, 1979), and electrolyte leakage (EL) (Lutts et al., 1996), ten leaf discs (area of 6 mm²) were used for each replicate. The analyses were performed 52 days after sowing (DAS). Due to the damage caused by severe salt stress, results for these variables could not be obtained at the salinity level of 6.5 dS m-1 at both MeJa concentrations.

Growth variables were evaluated at 52 DAS, including plant height (cm), number of leaves and tillers, root length (cm), and root volume (mL). The absolute (AGRPH) and relative (RGRPH) growth rates of plant height (Benincasa, 2003) were determined based on two sampling dates: the first at 15 DAS and the last at the end of the experiment, at 52 DAS.

After harvest, the plants were separated into shoot and root, placed in a forced-air oven at 65 °C and kept for four days until reaching constant weight, to determine shoot dry mass (SDM) and root dry mass (RDM), expressed in grams per plant.

Proline (Bates et al., 1973) and protein (Bradford et al., 1976) contents were quantified, and both analyses were performed at 66 DAS.

The data were subjected to analysis of variance, and in cases of significance, Tukey’s test was performed at p ≤ 0.05. Principal component analysis and Pearson’s correlation were performed to verify the association and correlation between the variables and treatments. The analyses were performed with the software R v.4.4.1 (R Core Team, 2023).

Results and Discussion

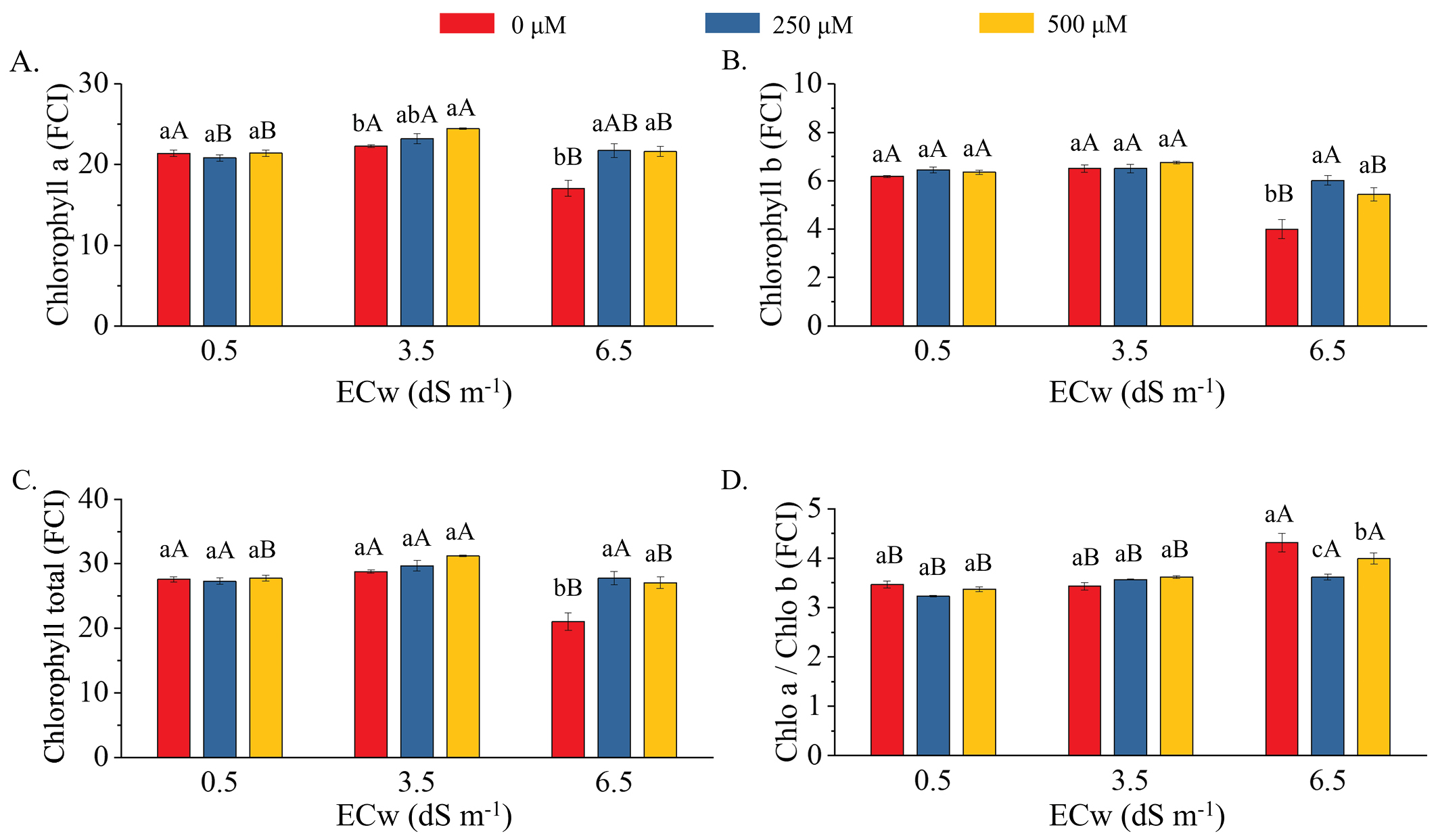

Regardless of MeJa concentration, salinity of 3.5 dS m-1 did not reduce chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b or chlorophyll total compared to the control salinity level (0.5 dS m-1). However, at 6.5 dS m-1, there were reductions of 20.1, 35.3, and 23.5% in chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and chlorophyll total contents, respectively, compared to the ECw of 0.5 dS m-1 (Figures 2A, B and C). For chlorophyll a, the application of 500 μM MeJa increased the content by 9.9% at 3.5 dS m-1 and by 27.5 and 26.3% at 6.5 dS m-1 with 250 and 500 μM, respectively, compared to the 0 μM MeJa concentration (Figure 2A). For chlorophyll b, MeJa had no effect at 0.5 and 3.5 dS m-1 (Figure 2B). However, at 6.5 dS m-1, its application increased chlorophyll b by 50.3 and 36.0% at 250 and 500 μM, respectively, compared to 0 μM. At 6.5 dS m-1, MeJa increased total chlorophyll content by 31.8 and 28.4% with 250 and 500 μM, respectively (Figure 2C). It also reduced the chlorophyll a/b ratio by 16.3 and 7.0% with 250 and 500 μM, respectively, compared to the condition without MeJa application (Figure 2D).

Chlorophyll a (A), chlorophyll b (B), chlorophyll total (C) and chlorophyll a/chlorophyll b ratio (D) in red rice plants under levels of electrical conductivity of irrigation water (ECw: 0.5, 3.5, and 6.5 dS m-1) and concentrations of methyl jasmonate (0, 250, and 500 μM)

In this study, foliar application of MeJa increased the contents of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and chlorophyll total, helping to protect the chloroplast membranes and acting as a defense mechanism against salt stress (Lopes et al., 2024). Methyl jasmonate mitigates the effects of salinity by reducing oxidative damage to thylakoid membranes through the activation of enzymes that scavenge free radicals (Faghih et al., 2017; Kalaji et al., 2018; Lopes et al., 2024).

Applying 250 μM of Meja at 3.5 dS m-1 resulted in reductions of 12.9% for initial fluorescence (F0), 13.9% for maximum fluorescence (Fm), and 14.0% for variable fluorescence (Fv), compared to the treatment without MeJa application (Figures 3A, B, and C). At 6.5 dS m-1, the application of 500 μM reduced Fm and Fv by 12.2 and 12.7%, respectively (Figures 3B and C). Potential quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm) did not show differences with the increase in salinity or the application of MeJa (Figure 3D).

Initial fluorescence - F0 (A), maximum fluorescence - Fm (B), variable fluorescence - Fv (A), and potential quantum yield of PSII - Fv/Fm (D) in red rice plants under levels of electrical conductivity of irrigation water (ECw: 0.5, 3.5, and 6.5 dS m-1) and concentrations of methyl jasmonate (0, 250, and 500 μM)

Fm, Fv and Fv/Fm, which indicate damage and photosynthetic performance, are reduced in sensitive rice varieties under salt stress (Tsai et al., 2019). These variables are essential for assessing photosynthetic efficiency. However, in the present study, even under severe salinity stress (6.5 dS m-1), they maintained their basic functionality, including in the control treatment (without MeJa application), suggesting a possible intrinsic tolerance of the red rice cultivar used regarding the integrity of PSII. Previous studies indicate that cultivars less sensitive to salt stress tend to accumulate fewer toxic ions in chloroplasts, thus preserving the functionality of the PSII reaction center (Zuo et al., 2024). Furthermore, the application of MeJa may have contributed to this photosynthetic stability by preserving the thylakoid structure, increasing antioxidant activity, and reducing oxidative damage, as reported by Hussain et al. (2022) and Lopes et al. (2024). These combined effects help maintain potential quantum yield (Fv/Fm) and fluorescence levels even under salt stress, as observed in other species (Faghih et al., 2017; Shekhar et al., 2023).

At the 3.5 dS m-1 level, salt stress reduced gas exchange, affecting net CO2 assimilation rate (A), stomatal conductance (gs), and transpiration (E), compared to the 0.5 dS m-1 level (Figure 4). Applying 250 and 500 μM of MeJa at this salinity level increased A by 49.74 and 41.06%, respectively, compared to the treatment without MeJa application (Figure 4A). However, for gs, E and internal CO2 concentration (Ci), there were no significant differences between the MeJa concentrations, nor compared to the control (0 μM), at 3.5 dS m-1 (Figures 4B, C and D).

Net CO2 assimilation rate - A (A), stomatal conductance - gs (B), transpiration - E (C), and internal CO2 concentration - Ci (D) in red rice plants under levels of electrical conductivity of irrigation water (ECw: 0.5, 3.5, and 6.5 dS m-1) and concentrations of methyl jasmonate (0, 250, and 500 μM)

Under salt stress, the observed reductions in gas exchange parameters indicate limitations in the photosynthetic performance of the plants. These effects may be associated with lower water uptake, leading to stomatal closure and reduced CO2 assimilation (Zhao et al., 2021; Lopes et al., 2024). Furthermore, the accumulation of toxic ions such as Na⁺ and Cl⁻ can impair the activity of RuBisCO (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase), further reducing photosynthetic efficiency. In this study, these limitations were evident at 3.5 dS m-1, where reductions in net CO2 assimilation rate (A), stomatal conductance (gs) and transpiration (E) were observed. However, the application of MeJa at 250 and 500 μM under moderate salinity (3.5 dS m-1) promoted significant increases in net CO2 assimilation rate, demonstrating its effectiveness in mitigating salt-induced damage. This effect is likely due to the role of MeJa in increasing antioxidant activity, maintaining membrane stability, and protecting photosynthetic enzymes and stomatal function under stress (Hussain et al., 2022; Ahmed et al., 2023).

Instantaneous water use efficiency (WUE), intrinsic water use efficiency (iWUE), and carboxylation efficiency (iCE) values decreased with increasing salinity (Figures 5A, B, and C). Applying MeJa did not result in increments in WUE (Figure 5A). For both iWUE and iCE, the application of MeJa mitigated the effects of salinity at 3.5 dS m-1. Increases of 26.78 and 32.90% in iWUE, and 56.07 and 47.66% in iCE were observed for MeJa concentrations of 250 and 500 μM, respectively, compared to the treatment without MeJa application (0 μM) at the salinity level of 3.5 dS m-1 (Figures 5B and C). Regarding VPD, the application of MeJa did not generate variations at any of the salinity levels. Regarding VPD, the application of MeJa did not generate variations in any of the salinity levels; however, salinity had a significant effect on VPD (Figure 5D).

Instantaneous water use efficiency - WUE (A), intrinsic water use efficiency - iWUE (B), carboxylation efficiency - iCE (C), and vapor pressure deficit - VPD (D) in red rice plants under levels of irrigation water electrical conductivity (ECw: 0.5, 3.5, and 6.5 dS m-1) and methyl jasmonate concentrations (0, 250, and 500 μM)

Salinity compromises plant water balance, reducing WUE. However, the application of MeJa to rice cultivars under salt stress alleviates these reductions, improving relative water content and membrane stability (Hussain et al., 2022). This suggests that MeJa can help maintain water balance in plants under salt stress (Hussain et al., 2022; Shekhar et al., 2023).

With exogenous application of MeJa at concentrations of 250 and 500 μM, there were increases in relative water content (RWC) of 67.06 and 56.0%, respectively, compared to the treatment without MeJa at the salinity level of 3.5 dS m-1 (Figure 6A). In addition, the application of MeJa at concentrations of 250 and 500 μM increased leaf moisture (LM) by 19.81 and 30.26%, respectively, compared to the treatment without MeJa at the level of 3.5 dS m-1 (Figure 6B).

Relative water content - RWC (A), leaf moisture - LM (B) and electrolyte leakage - EL (C) in red rice plants under levels of electrical conductivity of irrigation water (ECw: 0.5, 3.5 and 6.5 dS m-1) and concentrations of methyl jasmonate (0, 250 and 500 μM)

Salt stress exerts osmotic pressure on plants, reducing RWC and LM. However, the application of MeJa at both doses tested increased these variables under the saline condition of 3.5 dS m-1, contributing to the improvement of cellular hydration. This effect favored the water retention capacity of roots and plant tissues, even under salt stress. In addition, the increase in RWC can be attributed to the intensification of osmotic pressure in the cytoplasm, associated with osmolyte synthesis, which aids in the retention and absorption of water by cells (Hussain et al., 2022; Shekhar et al., 2023; Shiade et al., 2023).

Electrolyte leakage (EL) increased considerably with salinity (Figure 6C). At the 3.5 dS m-1 level, EL was 78.92% higher than at the 0.5 dS m-1 level, without the application of MeJa. The treatments with MeJa application did not show effect compared to those without application at the salinity level of 3.5 dS m-1 (Figure 6C). The increase in EL is related to damage caused to plasma membranes, which compromises their integrity and increases their permeability, resulting in more ion loss and, consequently, an increase in EL (Tavallali et al., 2019). The application of MeJa did not attenuate the effects of salinity on EL.

Salinity affected the growth parameters of red rice (Figures 7, 8, 9 and 10). Without the application of MeJa, there were reductions in plant height, number of leaves and number of tillers (Figure 7). Reductions occurred at all MeJa concentrations when plants were irrigated with 3.5 and 6.5 dS m-1, compared to 0.5 dS m-1 (Figure 7). With the application of MeJa at concentrations of 250 and 500 μM, plant height increased by 9.82 and 6.70%, respectively, at the salinity level of 3.5 dS m-1, when compared to the condition without MeJa application. At the 6.5 dS m-1 level, the greatest effect was observed with 500 μM of MeJa, resulting in a 4% increase in plant height, when compared to the condition without MeJa application (Figure 7A). In the number of leaves, the application of 500 μM of MeJa mitigated the adverse effects of salinity, promoting increases of 34.88 and 81.48% at salinity levels of 3.5 and 6.5 dS m-1, respectively, compared to the treatment without MeJa (Figure 7B). However, at both salinity levels, the application of MeJa did not increase the number of tillers (Figure 7C).

Plant height (cm) (A), number of leaves (B), and number of tillers (C) in red rice plants under levels of electrical conductivity of irrigation water (ECw: 0.5, 3.5, and 6.5 dS m-1) and concentrations of methyl jasmonate (0, 250, and 500 μM)

The lower plant height and number of leaves observed with increasing salinity occur because salinity induces osmotic and ionic stresses, which negatively affect cell expansion and division (Hussain et al., 2022). However, the application of MeJa mitigates these effects, possibly due to its role in maintaining ion homeostasis and reducing damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Quamruzzaman et al., 2021; Shekhar et al., 2023). Studies also highlight its effectiveness in enhancing salt stress resilience, thereby favoring plant growth (Zainordin et al., 2023).

Salinity reduced the values of absolute growth rate (AGRPH) and relative growth rate (RGRPH) of plant height in red rice. Applying MeJa at concentrations of 250 and 500 μM did not affect the absolute growth rate and relative growth rate at either salinity level (3.5 and 6.5 dS m-1). However, increasing salinity itself reduced both growth rates when compared to the control (0.5 dS m-1) (Figure 8).

Absolute growth rate - AGRPH (A) and relative growth rate - RGRPH (B) in red rice plants under levels of electrical conductivity of irrigation water (ECw: 0.5, 3.5, and 6.5 dS m-1) and concentrations of methyl jasmonate (0, 250, and 500 μM)

Salinity significantly reduced the absolute and relative growth rates of red rice. These effects are consistent with the findings of Xu et al. (2024), who reported that salt stress compromises plant growth due to nutritional imbalances and reduced photosynthetic activity.

For root length, the application of MeJa at 250 and 500 μM promoted increments of 89.41 and 71.76%, respectively, compared to the treatment without MeJa application under 3.5 dS m-1. Under 6.5 dS m-1, 500 μM of MeJa promoted an increase of 76.17% compared to 250 μM (Figure 9A). In root volume, at 250 μM and 3.5 dS m-1, there was an increase of 245%, compared to the control without MeJa (Figure 9B). The salinity levels severely reduced SDM and RDM (Figures 9C and D). At the salinity level of 3.5 dS m-1, MeJa showed no effect on shoot dry mass (SDM) (Figure 9C). However, the application of 250 μM increased root dry mass (RDM) by 144.4% compared to the treatment without MeJa (0 μM) (Figure 9D).

Root length (A), root volume (B), shoot dry mass - SDM (C), and root dry mass - RDM (D) in red rice plants under levels of electrical conductivity of irrigation water (ECw: 0.5, 3.5, and 6.5 dS m-1) and methyl jasmonate concentrations (0, 250, and 500 μM)

These results corroborate several recent studies that highlight the impacts of salt stress on plant physiology and growth, mainly due to the reduction in water and nutrient absorption and the osmotic imbalance caused by the high concentration of toxic ions such as Na⁺ and Cl⁻, which interfere with cellular metabolism and osmotic balance (Zainordin et al., 2023; Zuo et al., 2024).

With the increase in salinity levels, there was more damage to the plants, reducing the biomass at 3.5 and 6.5 dS m-1. However, MeJa, at concentrations of 250 and 500 μM, partially mitigated these effects up to 3.5 dS m-1, resulting in higher biomass compared to the condition in which MeJa was not applied (Figure 10). Ahmed et al. (2023) observed similar results, with 100 μM of MeJa improving the growth of wheat genotypes under salt stress, increasing root and shoot length by up to 13% and fresh weight by 21% in salt-tolerant genotypes.

Red rice plants under levels of electrical conductivity of irrigation water (0.5, 3.5, and 6.5 dS m-1) and concentrations of methyl jasmonate (0, 250, and 500 μM)

The soluble protein content was reduced with the increase in salinity, showing a decrease of 25.6% at the level of 6.5 dS m-1, compared to the level of 0.5 dS m-1 and the control without application of MeJa (Figure 11A). The application of MeJa influenced the soluble protein content, with reductions observed as its concentration increased. The reduction in proteins is attributed to salinity, which generates excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), affecting proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids and impairing membrane functionality due to increased lipoxygenase activity (Qin et al., 2020). Oxidative stress alters the electron transport chain through protein degradation, compromising the functionality of PSII (Kaya et al., 2020). Due to its similarities to K+, Na+ competes for binding sites, impairing essential metabolic processes such as protein synthesis, ribosomal functions, and enzymatic reactions (Khan et al., 2020). In addition, soluble proteins may have been hydrolyzed to increase amino acids, favoring nitrogen storage, cellular detoxification, and osmotic regulation in adversity (Javadipour et al., 2022). MeJa can preserve the structural integrity of proteins and maintain their functionality under stress conditions by reducing free radical generation and mitigating oxidative damage (Javadipour et al., 2022).

Soluble proteins (A) and proline (B) in red rice plants under levels of electrical conductivity of irrigation water (ECw: 0.5, 3.5, and 6.5 dS m-1) and concentrations of methyl jasmonate (0, 250, and 500 μM)

The proline content increased at all salinity levels with the application of MeJa (Figure 11B). The concentration of 250 μM raised the proline content by 118.91, 29.84, and 217.12% at salinity levels of 0.5, 3.5, and 6.5 dS m-1, respectively, compared to the concentration of 0 μM. The increase in proline levels under salt stress is a plant defense mechanism, as it acts as an osmoprotectant, antioxidant, and cellular stabilizer. Salinity triggers the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which causes osmotic imbalance. Proline helps mitigate these effects by scavenging ROS, preserving membranes and proteins, maintaining water balance, and supporting photosynthetic and respiratory processes (Ahmadi et al., 2018; Ghaffari et al., 2021). The application of MeJa stimulates the synthesis of enzymes responsible for proline biosynthesis, which is crucial for free radical detoxification, membrane stability, osmotic adjustment, and increased water content (Ahmad et al., 2017; Qin et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2021).

The sum of the principal components (PC) resulted in a total inertia of 78.54% of the total variation (Figure 12). PC1 contributed 63.39% of the total variation. It showed positive correlations with salinities of 0.5 dS m-1 (0, 250 and 500 μM) and 3.5 dS m-1 (250 and 500 μM), in addition to the variables of growth, gas exchange, fluorescence, biochemistry and photosynthetic pigments, except the Chlo a/b ratio, which showed a negative correlation. PC2 contributed 15.15% of the total variation and obtained a negative correlation with the Chlo a/b ratio and with the salinity of 6.5 dS m-1, regardless of the concentration, emphasizing that the salinity level of 6.5 dS m-1 affects some physiological aspects of this crop.

Principal component analysis between variables and treatments used in red rice plants under levels of electrical conductivity of irrigation water (ECw: 0.5, 3.5, and 6.5 dS m-1) and concentrations of methyl jasmonate (0, 250, and 500 μM)

The ratio between chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b (Chlo a/b) showed moderate negative correlations with the growth variables (PH, NL, NT, AGRPH, RGRPH, RL, RV, SDM, and RDM), with values ranging from -0.59 to -0.69. Strong negative correlations were also observed with the variables gs (-0.81) and E (-0.81) (Figure 13). In addition, a moderate negative correlation (-0.75) was recorded between proline and soluble proteins. This behavior is understandable, as the increase in proline is a plant response to stress, resulting from the destructuring of proteins caused by the intensity of salinity (Qin et al., 2020).

Conclusions

-

Application of methyl jasmonate at concentrations of 250 and 500 μM was effective in mitigating the adverse effects of moderate salt stress (3.5 dS m-1). However, it was not sufficient to completely reverse the damage caused by the more severe salinity level (6.5 dS m-1).

-

Methyl jasmonate concentration of 250 μM was most effective at the salinity level of 3.5 dS m-1, demonstrating a positive impact on root length and volume, gas exchange and chlorophyll.

Literature Cited

-

Ahmad, P.; Alyemeni, M. N.; Wijaya, L.; Alam, P.; Ahanger, M. A.; Alamri, S. A. Jasmonic acid alleviates negative impacts of cadmium stress by modifying osmolytes and antioxidants in faba bean (Vicia faba L.). Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science, v.63, p.1889-1899, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340.2017.1313406

» https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340.2017.1313406 -

Ahmadi, F. I.; Karimi, K.; Struik, P. C. Effect of exogenous application of methyl jasmonate on physiological and biochemical characteristics of Brassica napus L. cv. Talaye under salinity stress. South African Journal of Botany, v.115, p.5-11, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2017.11.018

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2017.11.018 -

Ahmed, I.; Abbasi, G. H.; Jamil, M.; Malik, Z. Exogenous Methyl jasmonate acclimate morpho-physiological, ionic and gas exchange attributes of wheat genotypes (Triticum aestivum L.) under salt stress. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies, v.32, p.1-14, 2023. https://doi.org/10.15244/pjoes/152882

» https://doi.org/10.15244/pjoes/152882 -

Alvares, C. A.; Stape, J. L.; Sentelhas, P. C.; Gonçalves, J. L. M.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorologische Zeitschrift. v.22, p.711-728, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1127/0941-2948/2013/0507

» https://doi.org/10.1127/0941-2948/2013/0507 -

Baptista, E.; Liberal, Â.; Cardoso, R. V. C.; Fernandes, Â.; Dias, M. I.; Pires, T. C. S. P.; Calhelha, R. C.; García, P. A.; Ferreira, I. C. F. R.; Barreira, J. C. M. Chemical and bioactive properties of Red Rice with potential pharmaceutical use. Molecules, v.29, e2265, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29102265

» https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29102265 -

Bates, L. S.; Waldren, R. P.; Teare, I. D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil, v.39, p.205-207, 1973. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00018060

» https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00018060 - Benincasa, M. M. P. Análise de crescimento de plantas: noções básicas. 3.ed. Jaboticabal: Funep, 2003. 41p.

-

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry, v.72, p.248-254, 1976. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3

» https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 -

Faghih, S.; Ghobadi, C.; Zarei, A. Response of strawberry plant cv.‘Camarosa’ to salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate application under salt stress condition. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, v.36, p.651-659, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-017-9666-x

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-017-9666-x -

Fu, X.; Ma, L.; Gui, R.; Ashraf, U.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Imran, M; Tang, X.; Tian, H.; Mo, Z. Differential response of fragrant rice cultivars to salinity and hydrogen rich water in relation to growth and antioxidative defense mechanisms. International Journal of Phytoremediation, v.23, p.1203-1211, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/15226514.2021.1889963

» https://doi.org/10.1080/15226514.2021.1889963 -

Ghaffari, H.; Tadayon, M. R.; Bahador, M.; Razmjoo, J. Investigation of the proline role in controlling traits related to sugar and root yield of sugar beet under water deficit conditions. Agricultural Water Management, v.243, e106448, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2020.106448

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2020.106448 -

Girardi, L. B.; Peiter, M. X.; Bellé, R. A.; Robaina, A. D.; Torres, R. R.; Kirchner, J. H.; Ben, L. H. B. Evapotranspiration and crop coefficients of potted Alstroemeria × Hybrida grown in greenhouse. Irriga, v.21, p.817-829, 2016. https://doi.org/10.15809/irriga.2016v21n4p817-829

» https://doi.org/10.15809/irriga.2016v21n4p817-829 -

Haque, M. A.; Rafii, M. Y.; Yusoff, M. M.; Ali, N. S.; Yusuff, O.; Datta, D. R.; Anisuzzaman, M.; Ikbal, M. F. Advanced breeding strategies and future perspectives of salinity tolerance in rice. Agronomy, v.11, e1631, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11081631

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11081631 -

Henschel, J. M.; Moura, V. S.; Silva, A. M. O.; Gomes, D. D. S.; Santos, S. K.; Batista, D. S.; Dias, T. J. Can exogenous methyl jasmonate mitigate salt stress in radish plants? Theoretical and Experimental Plant Physiology, v.35, p.51-63, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40626-023-00270-8

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s40626-023-00270-8 -

Hussain, S.; Zhang, R.; Liu, S.; Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hou, H.; Dai, Q. Methyl jasmonate alleviates the deleterious effects of salinity stress by augmenting antioxidant enzyme activity and ion homeostasis in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Agronomy, v.12, e2343, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12102343

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12102343 -

Irigoyen, J. J.; Einerich, D. W.; Sánchez‐Díaz, M. Water stress induced changes in concentrations of proline and total soluble sugars in nodulated alfalfa (Medicago sativa) plants. Physiologia Plantarum, v.84, p.55-60, 1992. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.1992.tb08764.x

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.1992.tb08764.x -

Javadipour, Z.; Balouchi, H.; Movahhedi Dehnavi, M.; Yadavi, A. Physiological responses of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) cultivars to drought stress and exogenous methyl jasmonate. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation , v.41, p.3433-3448, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-021-10525-w

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-021-10525-w -

Kalaji, H. M.; Račková, L.; Paganová, V.; Swoczyna, T.; Rusinowski, S.; Sitko, K. Can chlorophyll-a fluorescence parameters be used as bio-indicators to distinguish between drought and salinity stress in Tilia cordata Mill?. Environmental and Experimental Botany, v.152, p.149-157, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.11.001

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.11.001 -

Kaya, C.; Higgs, D.; Ashraf, M.; Alyemeni, M. N.; Ahmad, P. Integrative roles of nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide in melatonin‐induced tolerance of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) plants to iron deficiency and salt stress alone or in combination. Physiologia Plantarum , v.168, p.256-277, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.12976

» https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.12976 -

Khan, I.; Raza, M. A.; Awan, S. A.; Shah, G. A.; Rizwan, M.; Ali, B.; Tariq, R.; Hassan, M. J.; Alyemeni, M. N.; Brestic, M.; Zhang, X.; Ali, S.; Huang, L. Amelioration of salt induced toxicity in pearl millet by seed priming with silver nanoparticles (AgNPs): The oxidative damage, antioxidant enzymes and ions uptake are major determinants of salt tolerant capacity. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, v.156, p.221-232, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.09.018

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.09.018 -

Ku, Y. S.; Sintaha, M.; Cheung, M. Y.; Lam, H. M. Plant hormone signaling crosstalks between biotic and abiotic stress responses. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, v.19, e3206, 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19103206

» https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19103206 -

Lopes, A. S.; Dias, T. J.; Henschel, J. M.; da Silva, T. I.; de Moura, V. S.; Silva, A. M. O.; Ribeiro, J. E. S.; Diniz Neto, M. A.; Oliveira, A. B. O.; Batista, D. S. Methyl jasmonate mitigates salt stress and increases quality of purple basil (Ocimum basilicum L.). South African Journal of Botany , v.171, p.710-718, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2024.06.039

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2024.06.039 -

Lutts, S.; Kinet, J. M.; Bouharmont, J. NaCl-induced senescence in leaves of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars differing in salinity resistance. Annals of Botany, v.78, p.389-398, 1996. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1996.0134

» https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1996.0134 -

Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Qi, J.; Liu, X.; Guo, L.; Zhang, H. Research on the mechanisms of phytohormone signaling in regulating root development. Plants, v.13, e3051, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13213051

» https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13213051 -

Maibangsa, M.; Choudhury, D.; Maibangsa, S.; Sharma, K. K. Importance of red rice (Deep Water Rice) production and its potential of export from Dhemaji District of Assam. International Journal of Environment and Climate Change, v.13, p.4113-4118, 2023. https://doi.org/10.9734/IJECC/2023/v13i103088

» https://doi.org/10.9734/IJECC/2023/v13i103088 -

Peethambaran, P. K.; Glenz, R.; Höninger, S.; Shahinul Islam, S. M.; Hummel, S.; Harter, K.; Kolukisaoglu, Ü.; Meynard, D.; Guiderdoni, E.; Nick, P.; Riemann, M. Salt-inducible expression of OsJAZ8 improves resilience against salt-stress. BMC Plant Biology, v.18, p.1-15, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1521-0

» https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1521-0 - Pereira, J. A; Morais, O. P. As Variedades de arroz vermelho brasileiras; Teresina: Embrapa Meio-Norte Brasil. 1.ed. Teresina: Embrapa Meio-Norte, 2014. 39p.

-

Qin, C.; Ahanger, M. A.; Zhou, J.; Ahmed, N.; Wei, C.; Yuan, S.; Ashraf, M.; Zhang, L. Beneficial role of acetylcholine in chlorophyll metabolism and photosynthetic gas exchange in Nicotiana benthamiana seedlings under salinity stress. Plant Biology, v.22, p.357-365, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.13079

» https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.13079 -

Quamruzzaman, M.; Manik, S. N.; Shabala, S.; Zhou, M. Improving performance of salt-grown crops by exogenous application of plant growth regulators. Biomolecules, v.11, e788, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11060788

» https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11060788 -

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vieana: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2023. Available on: <Available on: https://www.r-project.org/ >. Accessed on: Dec. 2024.

» https://www.r-project.org/ -

Rachmawati, D.; Fatikhasari, Z.; Lestari, M. F. The potential of silicate fertilizer for salinity stress alleviation on red rice (Oryza sativa L. ‘Sembada Merah’). IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, v.423, e012041, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/423/1/012041

» https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/423/1/012041 - Santos, H. G. dos. Sistema brasileiro de classificação de solos. 5.ed. Brasília: Embrapa, 2018. 356p.

-

Shah, T.; Latif, S.; Saeed, F.; Ali, I.; Ullah, S.; Alsahli, A. A.; Jan, S.; Ahmad, P. Seed priming with titanium dioxide nanoparticles enhances seed vigor, leaf water status, and antioxidant enzyme activities in maize (Zea mays L.) under salinity stress. Journal of King Saud University-Science, v.33, e101207, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2020.10.004

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2020.10.004 -

Shekhar, S.; Mahajan, A.; Pandey, P.; Raina, M.; Rustagi, A.; Prasad, R.; Kumar, D. Salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate synergistically ameliorate salinity induced damage by maintaining redox balance and stomatal movement in potato. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation , v.42, p.4652-4672, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-023-10956-7

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-023-10956-7 -

Shiade, S. R. G.; Pirdashti, H.; Esmaeili, M. A.; Nematzade, G. A. Biochemical and physiological characteristics of mutant genotypes in rice (Oryza sativa L.) contributing to salinity tolerance indices. Gesunde Pflanzen, v.75, p.303-315, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10343-022-00701-7

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10343-022-00701-7 -

Silva, T. I. D.; Dias, M. G.; Lannes, S.; Domingues, P.; Sales, G. N.; Nóbrega, J. S.; Ribeiro, J. E. S.; Costa, F. B.; Soares, L. A. A.; Lima, G. S. Phytohormones mitigate salt stress damage in radish. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, v.28, e279042, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v28n7e279042

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v28n7e279042 - Slavick, B. Methods of studying plant water relations. New York: Springer Verlag, 1979. 449p.

-

Tavallali, V.; Karimi, S. Methyl jasmonate enhances salt tolerance of almond rootstocks by regulating endogenous phytohormones, antioxidant activity and gas-exchange. Journal of Plant Physiology, v.234, p.98-105, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2019.02.001

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2019.02.001 -

Tsai, Y. C.; Chen, K. C.; Cheng, T. S.; Lee, C.; Lin, S. H.; Tung, C. W. Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis in diverse rice varieties reveals the positive correlation between the seedlings salt tolerance and photosynthetic efficiency. BMC Plant Biology , v.19, p.1-17, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-1983-8

» https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-1983-8 -

United States. Soil Survey Staff. Keys to soil taxonomy. 12.ed. Lincoln: USDA NRCS, 2014. Available on: <Available on: http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/soils/survey/ >. Accessed on: May 2025.

» http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/soils/survey/ -

Wang, J.; Song, L.; Gong, X.; Xu, J.; Li, M. Functions of jasmonic acid in plant regulation and response to abiotic stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences , v.21, e1446, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21041446

» https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21041446 -

Wang, Y.; Mostafa, S.; Zeng, W.; Jin, B. Function and mechanism of jasmonic acid in plant responses to abiotic and biotic stresses. International Journal of Molecular Sciences , v.22, e8568, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22168568

» https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22168568 -

Xu, Y.; Bu, W.; Xu, Y.; Fei, H.; Zhu, Y.; Ahmad, I.; Nimir, N. E. A.; Zhou, G.; Zhu, G. Effects of salt stress on physiological and agronomic traits of rice genotypes with contrasting salt tolerance. Plants, v.13, e1157, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13081157

» https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13081157 -

Yang, J.; Duan, G.; Li, C.; Liu, L.; Han, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. The crosstalks between jasmonic acid and other plant hormone signaling highlight the involvement of jasmonic acid as a core component in plant response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Frontiers in Plant Science, v.10, e1349, 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01349

» https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01349 -

Zainordin, Z. F. M.; San Cha, T.; Ahmad, A. Foliar sprays of methyl jasmonic acid shift the endogenous fatty acid levels to support rice plant growth in saline soil. Plant Stress, v.10, e100221, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stress.2023.100221

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stress.2023.100221 -

Zhang, R.; Hussain, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wei, H.; Gao, P.; Dai, Q. Comprehensive evaluation of salt tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) germplasm at the germination stage. Agronomy, v.11, e1569, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11081569

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11081569 -

Zhao, S.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhou, H.; Ma, C.; Wang, P. Regulation of plant responses to salt stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences , v.22, e4609, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094609

» https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094609 -

Zhou, S.; Jander, G. Molecular ecology of plant volatiles in interactions with insect herbivores. Journal of Experimental Botany, v.73, p.449-462, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erab413

» https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erab413 -

Zuo, G.; Huo, J.; Yang, X.; Mei, W.; Zhang, R.; Khan, A.; Feng, N.; Zheng, D. Photosynthetic mechanisms underlying NaCl-induced salinity tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa). BMC Plant Biology , v.24, e41, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-024-04723-3

» https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-024-04723-3

Financing statement

Data availability

There are no supplementary sources.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

25 Aug 2025 -

Date of issue

Dec 2025

History

-

Received

29 Dec 2024 -

Accepted

20 June 2025 -

Published

16 July 2025

Methyl jasmonate as an attenuator of salt stress on the morphophysiological aspects of red rice

Methyl jasmonate as an attenuator of salt stress on the morphophysiological aspects of red rice

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

Means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ for methyl jasmonate, and means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ for irrigation water salinity according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05)

A - Net CO2 assimilation rate; gs - Stomatal conductance; E - Transpiration; Ci - Internal CO2 concentration; WUE - Instantaneous water use efficiency; iWUE - Intrinsic water use efficiency; iCE - Carboxylation efficiency; VPD - Vapor pressure deficit; Chlo a - Chlorophyll a; Chlo b - Chlorophyll b; T chlo - Total chlorophyll; Chlo a/b - Chlorophyll a/Chlorophyll b ratio; F0 - Initial fluorescence; Fm - Maximum fluorescence; Fv: Variable fluorescence, Fv/Fm - Potential quantum yield of PSII; RWC - Relative water content; LM - Leaf moisture; EL - Electrolyte leakage; PH - Plant height; NL - Number of leaves; NT - Number of tillers; AGRPH - Absolute growth rate; RGRPH - Relative growth rate; RL - Root length; RV - Root volume; SDM - Shoot dry mass; RDM - Root dry mass

A - Net CO2 assimilation rate; gs - Stomatal conductance; E - Transpiration; Ci - Internal CO2 concentration; WUE - Instantaneous water use efficiency; iWUE - Intrinsic water use efficiency; iCE - Carboxylation efficiency; VPD - Vapor pressure deficit; Chlo a - Chlorophyll a; Chlo b - Chlorophyll b; T chlo - Total chlorophyll; Chlo a/b - Chlorophyll a/Chlorophyll b ratio; F0 - Initial fluorescence; Fm - Maximum fluorescence; Fv: Variable fluorescence, Fv/Fm - Potential quantum yield of PSII; RWC - Relative water content; LM - Leaf moisture; EL - Electrolyte leakage; PH - Plant height; NL - Number of leaves; NT - Number of tillers; AGRPH - Absolute growth rate; RGRPH - Relative growth rate; RL - Root length; RV - Root volume; SDM - Shoot dry mass; RDM - Root dry mass

A - Net CO2 assimilation rate; gs - Stomatal conductance; E - Transpiration; Ci - Internal CO2 concentration; WUE - Instantaneous water use efficiency; iWUE - Intrinsic water use efficiency; iCE - Carboxylation efficiency; VPD - Vapor pressure deficit; Chlo a - Chlorophyll a; Chlo b - Chlorophyll b; Chlo T - Chlorophyll total; Chlo a /Chlo b - Chlorophyll a/Chlorophyll b ratio; F0 - Initial fluorescence; Fm - Maximum fluorescence; Fv: Variable fluorescence, Fv/Fm - Potential quantum yield of PSII; RWC: Relative water content; LM: Leaf moisture; EL: Electrolyte leakage; PH - Plant height; NL - Number of leaves; NT - Number of tillers; AGRPH - Absolute growth rate; RGRPH - Relative growth rate; RL - Root length; RV - Root volume; SDM - Shoot dry mass; RDM - Root dry mass

A - Net CO2 assimilation rate; gs - Stomatal conductance; E - Transpiration; Ci - Internal CO2 concentration; WUE - Instantaneous water use efficiency; iWUE - Intrinsic water use efficiency; iCE - Carboxylation efficiency; VPD - Vapor pressure deficit; Chlo a - Chlorophyll a; Chlo b - Chlorophyll b; Chlo T - Chlorophyll total; Chlo a /Chlo b - Chlorophyll a/Chlorophyll b ratio; F0 - Initial fluorescence; Fm - Maximum fluorescence; Fv: Variable fluorescence, Fv/Fm - Potential quantum yield of PSII; RWC: Relative water content; LM: Leaf moisture; EL: Electrolyte leakage; PH - Plant height; NL - Number of leaves; NT - Number of tillers; AGRPH - Absolute growth rate; RGRPH - Relative growth rate; RL - Root length; RV - Root volume; SDM - Shoot dry mass; RDM - Root dry mass