ABSTRACT

Proper management of irrigation with brackish water can reduce the deleterious effects of salt stress on the peanut crop, considering application at more tolerant stages. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of salt stress applied at different phenological stages of the peanut crop. The experiment was conducted from February to April 2023 in an arch-type greenhouse. A completely randomized experimental design was used, with eight treatments and six replications, corresponding to strategies of irrigation with brackish water in the phenological stages: use of low-salinity water (W1 = 0.8 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; use of high-salinity water (W2 = 4.0 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; use of W2 only in the flowering and pod formation phases; use of W2 only in the vegetative and gynophore formation phases; use of W2 in the gynophore formation phase; use of W2 in the vegetative and flowering phases; use of W2 in the pod formation phase; use of W2 in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases. It is possible to irrigate the peanut crop with high-salinity water without production losses during the flowering, pod formation and gynophore formation phases. Irrigation with brackish water during the vegetative and flowering stages significantly reduces the average mass of peanut pods. In contrast, irrigation during the pod formation stage more strongly affects pod length and diameter.

Key words:

Arachis hypogea L.; salinity; phenological stage; photosynthetic activity; production components

HIGHLIGHTS:

Water use efficiency of peanut decreased when irrigated with 4.0 dS m-1 water during the vegetative stage.

Production of peanut was not affected by irrigation with brackish water (4.0 dS m-1) during the flowering and fruiting stages.

Peanut production is severely reduced by salt stress applied during the pod formation stage (37-80 DAS).

RESUMO

O manejo adequado da irrigação com água salobra, pode reduzir os efeitos deletérios do estresse salino na cultura do amendoim, considerando a aplicação em fases mais tolerantes. Assim, objetivou-se avaliar os efeitos do estresse salino aplicado em diferentes estágios fenológicos da cultura do amendoim. O experimento foi realizado entre fevereiro e abril de 2023, em estufa agrícola do tipo arco. Foi utilizado o delineamento experimental inteiramente casualizado, com oito tratamentos e seis repetições, correspondendo a estratégias de irrigação com água salobra nas diferentes fases fenológicas: uso de água de menor salinidade (W1 = 0,8 dS m-1) durante todo o ciclo da cultura; uso de água de alta salinidade (W2 = 4,0 dS m-1) durante todo o ciclo da cultura; uso de W2 apenas nas fases de florescimento e formação de vagens; uso de água W2 apenas nas fases vegetativa e formação do ginóforo; uso W2 na fase de formação do ginóforo; uso de W2 nas fases vegetativa e florescimento; uso de W2 nas fase de formação de vagens; uso de W2 nas fases vegetativa, florescimento e formação do ginóforo. É possível irrigar a cultura do amendoim com água de alta salinidade, sem perdas de produção durante as fases de florescimento, formação de vagens e ginóforo. A irrigação com água salobra durante os estágios vegetativo e de floração reduz significativamente a massa média das vagens de amendoim. Em contraste, a irrigação durante a fase de formação das vagens afeta mais fortemente o comprimento e o diâmetro das vagens.

Palavras-chave:

Arachis hypogea L.; salinidade; estágio fenológico; atividade fotossintética; componentes de produção

Introduction

Peanut (Arachis hypogea L.) is a legume crop of great nutritional importance, providing high quality protein and vegetable oil (Santos et al., 2021). It is also rich in essential fatty acids, vitamins and minerals, making it a crop with multiple uses (Alves et al., 2022). It is one of the most produced oilseeds in Brazil, with an average yield of 2,873 kg ha-1, and the southeastern region of Brazil has the highest production, especially the states of São Paulo and Minas Gerais (CONAB, 2024).

The Northeast is the second largest consumer in the country, which has led to the expansion of its cultivation in the region (Sousa et al., 2023a). However, the Brazilian semi-arid region is characterized by seasonal and irregular rainfall with high evapotranspiration rates, poorly developed soils, and fractured crystalline aquifers, which favors the concentration of soluble salts and can cause various problems in the soil and plants (Lessa et al., 2023; Queiroz et al., 2023; Oliveira et al., 2024).

Under these conditions, irrigation is essential in these areas to increase agricultural production. However, most water sources have high levels of salts, resulting in the accumulation of toxic ions such as Na+ and Cl-, inducing stomata closure, reducing transpiration and the rate of CO2 assimilation, and reducing agricultural yields (Sousa et al., 2023b; Barbosa et al., 2024).

The use of brackish water at different phenological stages of agricultural crops is an effective strategy to mitigate the negative effects of salt stress as plant tolerance varies according to the phenological stage (Lima et al., 2022; Semedo et al., 2024). A study with peanut crop under brackish water irrigation strategies conducted by Cruz Filho et al. (2024) revealed that applying 4.0 dS m-1 water from 25 and 35 days after sowing did not affect production. Abreu et al. (2024), evaluating salt stress at different phenological stages of the peanut crop, observed that the continuous application of brackish water during 66 days led to a decrease in production.

Thus, the hypothesis of the present study is that peanut crop shows different responses to the presence of salts in its phenological stages, so it is possible to identify more tolerant phases in order to manage irrigation with brackish water efficiently. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of salt stress applied at different phenological stages of the peanut crop.

Material and Methods

The experiment was conducted from February to April 2023 in an arch-type greenhouse, covered with 150-micron agricultural diffuser plastic, with a galvanized steel structure and dimensions of 8 × 15 m, at the Unidade de Produção de Mudas Auroras (UPMA), belonging to the Universidade da Integração Internacional da Lusofonia Afro-Brasileira (UNILAB), Redenção, Ceará state, Brazil (04° 14’ 53” S and 38° 45’ 10” W and altitude of 240 m above sea level).

The region’s climate is tropical semi-arid, with very high temperatures and predominant rainfall in summer and fall. The ideal temperature range for peanut growth is between 25 and 35 °C (Santos et al., 2021). The maximum and minimum air temperature was recorded daily throughout the experiment, as was the mean relative air humidity (Figure 1), monitored using a Datalogger (HOBO® U12-012 Temp/RH/Light/Ext, Bourne, MA, USA).

Mean values of maximum (Max) and minimum (Min) temperature and relative air humidity obtained during the experimental cycle (06 February to 27 April 2023)

The experiment was conducted in a completely randomized design, with eight treatments and six replications. The treatments corresponded to strategies of irrigation with brackish water in the phenological stages: S1 = use of low-salinity water (W1 = 0.8 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S2 = use of high-salinity water (W2 = 4.0 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S3 = use of W2 only in the flowering and pod formation phases; S4 = use of W2 only in the vegetative and gynophore formation phases; S5 = use of W2 in the gynophore formation phase; S6 = use of W2 in the vegetative and flowering phases; S7 = use of W2 in the pod formation phase; S8 = use of W2 in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases.

A graphical representation of the phenological phases used in the treatments is shown in Figure 2. Table 1 presents the distribution of irrigation strategies according to the phenological stages established, along with the respective levels of electrical conductivity of the water used in irrigation.

The seeds used came from the peanut cv. BR-1, belonging to the Valencia group, red in color and rounded in shape; it is an erect cultivar, with pods of three to four seeds, and mean oil content of 45%. It has an early cycle of around 90 days and a yield potential of 1,700 kg ha-1 in shells when grown in the rainy season and 3,800 kg ha-1 under irrigated conditions. The cultivar is suitable for planting in the most diverse regions of Brazil (Santos et al., 2009). Sowing was carried out at a depth of 2 cm in polyethylene pots adapted as micro-lysimeters with a capacity of 11 dm3 containing as substrate a mixture of arisco (a light-textured sandy material normally used in construction in the northeast of Brazil), sand and bovine manure in a ratio of 7:2:1 (v/v), respectively, whose chemical characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Mineral fertilization was based on the chemical analysis of the substrate (Table 2), with the recommendation based on the maximum dose for the crop (Fernandes, 1993), which includes 15 kg ha-1 N, 62.5 kg ha-1 P2O5 and 50 kg ha-1 K2O. With a stand of 10,000 plants, the maximum dose per plant-1 in the cycle was 1.5 g N, 6.25 g P2O5 and 5.0 g K2O, using urea (45% N), single superphosphate (18% P2O5, 16% Ca, and 10% S) and potassium chloride (60% K2O) as sources of N, P and K, respectively, with all the N applied in the basal dressing and the P and K applied 50% in the basal dressing and 50% in the top dressing (20 DAS).

To prepare water with an electrical conductivity of 4.0 dS m-1, the soluble salts NaCl, CaCl2.2H2O and MgCl2.6H2O were dissolved in the local-supply water (0.8 dS m-1), maintaining the proportions predominantly found in the principal water sources of the northeast of Brazil, i.e., ratio of 7:2:1, respectively, according to the relationship between ECw and the concentration of salts in water (mmolc L-1 = ECw × 10), as described by Richards (1954). The electrical conductivity of water (ECw) levels were based on a study conducted by Sousa et al. (2023).

Irrigation was carried out manually, daily, using the water balance calculated according to the principle of the drainage lysimeter, adapting the pots (11 dm³) as micro-lysimeters to maintain the soil at field capacity, according to Eq. 1. A 10% leaching fraction was considered for each irrigation event to avoid excessive salt accumulation according to Ayers & Westcot (1999).

where:

VI - volume of water to be applied in the irrigation event (mL);

Vp - volume of water applied in the previous irrigation event (mL);

Vd - volume of water drained (mL); and,

LF - leaching fraction of 0.10;

At 48 DAS, after the plants entered the last phenological stage (pod maturation) the CO2 assimilation rate (A, µmol CO2 m-2 s-1), transpiration (E, mmol H2O m-2 s-1), internal CO2 concentration (Ci, mmol CO2 m-2 s-1) and leaf temperature (LT, ºC) were determined using an IRGA - infrared gas analyser (Li-6400XT, LICOR, Lincoln, NE, USA), on a fully expanded upper third leaf, in an open system with an air flow of 300 mL min-1, and photosynthetically active radiation of 1,600 µmol m−2s−1. Measurements were made between 8:00 and 10:00 h. The instantaneous water use efficiency (A/E - WUEi) was also quantified. The relative chlorophyll index (RCI) was measured on the same leaves using the non-destructive method with a portable instrument (SPAD - 502 Plus, Minolta, Japan).

At the end of the experimental cycle (80 DAS), the pods were harvested and dried for about 72 h in a forced air circulation oven at 75 ºC temperature until they reached a constant mass. The total number of pods per plant (TNP) was then determined; the average pod mass (APM, g) was determined using a precision analytical scale; the pod length (PL, mm) and diameter (PD, mm) were measured by longitudinal and transverse measurements, respectively, with a digital caliper; and the production (PRO, g per plant) was determined by weighing on a precision scale.

To assess normality, data were subjected to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (p ≤ 0.05). After verifying normality, the data were subjected to analysis of variance using the F test (p ≤ 0.05), and when significant, were compared by Tukey test (p ≤ 0.05) using Assistat 7.7 Beta software (Silva & Azevedo, 2016).

Results and Discussion

According to the analysis of variance, the variables CO2 assimilation rate, relative chlorophyll index and instantaneous water use efficiency (WUEi) were significantly influenced by the strategies (p ≤ 0.01). However, the other variables analyzed, namely leaf transpiration, leaf temperature, and internal CO2 concentration, were not influenced by the irrigation strategies applied (Table 3).

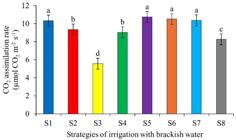

The CO2 assimilation rate of plants under strategies S5, S6 and S7 (use of W2 in the gynophore formation phase; use of W2 in the vegetative and flowering phases; use of W2 in the pod formation phase, respectively) showed similar values to those found under strategy S1 (without salt stress). On the other hand, strategy S3 resulted in the lowest CO2 assimilation rate among all the strategies evaluated (5.57 µmol CO2 m-2 s-1), indicating the sensitivity of the crop in the flowering and pod formation phases (Figure 3).

CO2 assimilation rate of peanut crop under different strategies of irrigation with brackish water

This result indicates that salt stress in specific phases (flowering and pod formation) can significantly affect peanuts, similarly to continuous salt stress (S2). The reduction in the CO2 assimilation rate is attributed to the decrease in osmotic potential, which affects the ability of plants to absorb essential elements for photosynthesis as well as reducing water absorption and inhibiting cell expansion (Souto et al., 2022; Semedo et al., 2024).

This result differs from that found by Barbosa et al. (2022), who observed that salinity did not affect the rate of CO2 assimilation in peanut plants subjected to salt stress during the vegetative and flowering phases. Lessa et al. (2021), evaluating the peanut cultivar BR-1 under conditions of high salinity in the irrigation water (5.0 dS m-1) in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases, observed a significant reduction in photosynthesis compared to the control.

The relative chlorophyll index was affected by salinity at different phenological stages, and strategy S4 showed the lowest index among all the strategies (31.07), corresponding to a 19.13% reduction compared to the treatment without salt stress throughout the cycle, indicating that the vegetative phases and the appearance of the gynophore are more affected by salt stress (Figure 4).

Relative chlorophyll index of peanut crop under different strategies of irrigation with brackish water

The reduction in chlorophyll index may be related to the reduced uptake of water and mineral nutrients caused by the osmotic effect, which affects the function of the pigment-protein complex and reduces the uptake and conversion of light energy by chloroplasts (Guo et al., 2021). These results differ from those of Freitas et al. (2021), who found a reduction in the relative chlorophyll index in peanut under different electrical conductivities of irrigation water during the vegetative and flowering phases.

Irrigation strategies S1, S5 and S7 promoted the highest WUEi rates (4.15, 4.71 and 4.35 [µmol CO2 m-2 s-1. (mmol H2O m-2 s-1)-1], respectively). However, when brackish water was applied throughout the cycle (S2), in the flowering and pod formation phases (S3) and in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases (S8), the efficiency was significantly reduced (17.59, 43.37, and 16.38%, respectively) by salinity compared to the control (Figure 5).

Instantaneous water use efficiency of peanut crop under different strategies of irrigation with brackish water

The instantaneous water use efficiency represents the ratio between photosynthesis and leaf transpiration, i.e., the more carbon the plant can assimilate in relation to the water lost through transpiration, the higher the water use efficiency (Taiz et al., 2017). Thus, the effect of salinity at some stages is clear, as it reduces the absorption of water and nutrients, reduces the opening of stomata (structures responsible for gas exchange) and reduces the rate of photosynthesis, which may increase the production of free radicals that damage cells (Guo et al., 2021; Sousa et al., 2023), especially in the S3 strategy, where plants allocate most of their resources to fruit (pod) development at this stage (Goes et al., 2021). The high salinity during this period may have affected these processes, reducing the efficiency of water use.

Results similar to those observed in the present study were reported by Lessa et al. (2021), who found that salinity affected peanuts up to the gynophore formation stage. The same authors also observed a significant reduction in WUEi with increasing irrigation water salinity. Similarly, Freitas et al. (2021) studied the leaf gas exchange of peanut and observed a 63% decrease in WUEi with increasing salinity of the irrigation water.

As can be seen in Table 4, all the production variables, namely total number of pods, pod length, pod diameter, average pod mass and production, were significantly influenced by the irrigation strategies (p ≤ 0.05).

Strategies S1, S2, S3, S4, S6, and S8 showed no significant difference, with the higher values in the total number of pods (Figure 6A). On the other hand, the treatments that applied brackish water at critical stages of development, such as gynophore formation (S5) and pod formation (S7), resulted in a significant reduction in the total number of pods (Figure 6A).

Total number of pods (A), pod length (B), pod diameter (C), and average pod mass (D) of peanut crop under different strategies of irrigation with brackish water

This behavior shows the sensitivity of the gynophore and pod formation phases, since during this period peanut plants transfer a large part of their assimilates (water and nutrients, especially calcium and phosphorus) - macronutrients of considerable importance to the crop, as calcium deficiency can possibly lead to deformed pods due to its involvement in the growth of young tissues, and phosphorus is essential for energy metabolism and therefore possibly influences pod growth (Freitas et al., 2021; Oliveira et al., 2024). Thus, the osmotic and nutritional effects of salt stress have a direct impact on these processes, in which plants absorb less water and, consequently, lower quantities of elements essential for the development of production parameters (Goes et al., 2021; Santos et al., 2021).

Similar results were reported by Goes et al. (2021), who observed a reduction in the total number of pods when peanut crop was irrigated throughout the entire crop cycle with water of 4.0 dS m-1, compared to 1.0 dS m-1. Confirming the sensitivity of the crop, Guilherme et al. (2021) observed a reduction in the total number of peanut pods under salinity stress at similar stages to those of the present study (flowering and appearance of the gynophore).

Irrigation strategies S1, S2, S3, S4, S5 and S8 had a negative effect on peanut pod length but were not statistically different from each other. On the other hand, the strategy S6 produced the longest pods of 24.52 mm, representing percentage increases of 21.16% over the shortest length treatment (S7) (Figure 6B). The tolerance to salt stress shown by the peanut in the phases before pod formation may be associated with ion homeostasis mechanisms, such as the reduction in sodium concentration in the cells, which may have been induced by the late and/or fractionated application of salt stress (Semedo et al., 2024), resulting in longer pods.

Results similar to those found in the present study were reported by Abreu et al. (2024), who observed a reduction in pod length as a result of salt stress throughout the cycle and in the phases prior to pod formation. Guilherme et al. (2021) reported that salt stress applied during the flowering phase (beginning at 29 DAS) reduced the length of peanut pods, associated with lower tolerance at this stage.

For pod diameter (Figure 6C), it was observed that strategies S1, S3, S4, S6, and S8 resulted in the higher values, significantly differing from the other treatments. However, strategies S2 (use of high-salinity water throughout the crop cycle) and S7 (higher salinity water only in the pod formation stage) led to the lowest values for the same variable, with reductions of 17.34 and 16.51%, respectively, compared to the control treatment, indicating a negative effect of brackish water application during the pod formation stage.

The salt stress applied to the plants in the flowering and pod formation (S3) and in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases (S8) may not have caused an antagonistic effect of elements such as Na and P (Abreu et al., 2024), which explains the positive effect observed in strategies S3 and S8. Similar results were reported by Goes et al. (2021) in a study using brackish water to irrigate peanut crop throughout the entire cycle, as a reduction in pod diameter was observed under salt stress.

Regarding the average pod mass, statistically higher values were observed with the use of strategy S3, as shown in Figure 6D. The reduction in pod mass observed in the other strategies, except strategy S1, can be explained by the detrimental effects of excess soluble salts, such as reduced water and nutrient (N, P, K, and Ca) absorption (Taiz et al., 2017), which directly affect the growth and production parameters.

Higher production values were observed with the use of strategies S1 and S3, but a decrease was observed with strategy S2, which had the lowest values, approximately 46.14% lower compared to the control (S1) (Figure 7). This decrease in production caused by the use of saline water throughout the cycle is partly due to a decrease in transpiration and instantaneous water use efficiency, leading to a decrease in photosynthetic efficiency and photoassimilate production (Lessa et al., 2021), which explains the decrease in production.

Similar results were reported by Abreu et al. (2024), who observed increases in yield when saline water irrigation was applied during the reproductive stages (flowering and appearance of the gynophore), compared to the control treatment irrigated with low-salinity water throughout the entire crop cycle. Guilherme et al. (2021), when evaluating saline water irrigation in peanut crop at different phenological stages, also observed yield increases in plants subjected to salt stress during the late flowering stage, compared to those stressed during the vegetative, early flowering, and gynophore appearance stages.

Conclusions

-

Irrigation with water up to electrical conductivity of 4.0 dS m-1 can be applied to peanut crop without production loss during flowering, pod formation and gynophore formation stages.

-

CO2 assimilation rate, relative chlorophyll index and instantaneous water use efficiency are reduced when peanut plants were irrigated with water of higher electrical conductivity (4.0 dS m-1) during the flowering and pod formation phases.

-

Irrigation with brackish water during the vegetative and flowering stages significantly reduces the average mass of peanut pods. In contrast, irrigation during the pod formation stage more strongly affects pod length and diameter.

Acknowledgments

To Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and to National Institute of Science and Technology in Sustainable Agriculture in the Tropical Semiarid Region - INCTAgriS (CNPq/FUNCAP/CAPES).

Literature Cited

-

Abreu, F. S.; Viana, T. V. A.; Sousa, G. G.; Baldé, B.; Lacerda, C. F.; Goes, G. F.; Gomes, K. R.; Cambissa, P. B. C. Salt stress and potassium fertilization on the agronomic performance of peanut crop. Revista Caatinga, v.37, e11996, 2024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1983-21252024v3711996rc

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1983-21252024v3711996rc -

Alves, R. de C.; Oliveira, K. R.; Lúcio, J. C. B.; Silva, J. dos S.; Carrega, W. C.; Queiroz, S. F.; Gratão, P. L. Exogenous foliar ascorbic acid applications enhance salt-stress tolerance in peanut plants through increase in the activity of major antioxidant enzymes. South African Journal of Botany, v.150, p.759-767, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2022.08.007

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2022.08.007 - Ayers, R. S.; Westcot, D. W. A qualidade da água na agricultura. 2.ed. Campina Grande: UFPB, 1999. 153p. Estudos FAO: Irrigação e Drenagem, 29.

-

Barbosa, A. S.; Sousa, G. G.; Freire, M. H. C.; Leite, K. N.; Silva, F. D. B.; Viana, T. V. A. Gas exchange and growth of peanut crop subjected to saline and water stress. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, v.26, p.557-563, 2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v26n8p557-563

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v26n8p557-563 -

CONAB - Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento (2024). Acompanhamento da safra brasileira de grãos: safra 2024/2025. Available: <Available: https://www.conab.gov.br/info-agro/safras/graos/boletim-da-safra-de-graos >. Accessed on: Nov. 2024.

» https://www.conab.gov.br/info-agro/safras/graos/boletim-da-safra-de-graos -

Cruz Filho, E. M.; Sousa, G. G.; Ribeiro, R. M. R.; Cambissa, P. B. C.; Souza, M. V. P.; Nogueira, R. S. Estratégias de irrigação com água salobra e adubação na cultura do amendoim. Nativa, v.12, p.20-25, 2024. https://doi.org/10.31413/nat.v12i1.14047

» https://doi.org/10.31413/nat.v12i1.14047 - Fernandes, V. L. B. Recomendações de adubação e calagem para o estado do Ceará. Fortaleza: UFC, 1993. 248p.

-

Freitas, A. G. S.; Sousa, G. G.; Sales, J. R. S.; Silva Junior, F. B. da; Barbosa, A. S.; Guilherme, J. M. S. Morfofisiologia da cultura do amendoim cultivado sob estresse salino e nutricional. Revista Brasileira de Agricultura Irrigada, v.15, p.48-57, 2021. https://doi.org/10.7127/rbai.v1501201

» https://doi.org/10.7127/rbai.v1501201 -

Goes, G. F.; Sousa, G. G.; Santos, S. O.; Silva Junior, F. B.; Ceita, E. D. R.; Leite, K. N. Produtividade da cultura do amendoim sob diferentes supressões da irrigação com água salina. Irriga, v.26, p.210-220, 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.15809/irriga.2021v26n2p210-220

» http://dx.doi.org/10.15809/irriga.2021v26n2p210-220 -

Guilherme, J. M. S.; Sousa, G. G.; Santos, S. O.; Gomes, K. R.; Viana, T. V. A. Água salina e adubação fosfatada na cultura do amendoim. Irriga, v.1, p.704-713, 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.15809/irriga.2021v1n4p704-713

» http://dx.doi.org/10.15809/irriga.2021v1n4p704-713 -

Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Gul, Z.; Guo, X.-R.; Abozeid, A.; Tang, Z.-H. Effects of exogenous calcium on adaptive growth, photosynthesis, ion homeostasis and phenolics of Gleditsia sinensis Lam. plants under salt stress. Agriculture, v.11, e978, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11100978

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11100978 -

Lessa, C. I. N.; Lacerda, C. F.; Cajazeiras, C. C. A.; Neves, A. L. R.; Lopes, F. B.; Silva, A. O.; Sousa, H. C.; Gheyi, H. R.; Nogueira, R. S.; Lima, S. C. R. V.; Costa, R. N. T.; Sousa, G. G. Potencial of brackish groundwater for different biosaline agriculture systems in the Brazilian semi-arid region. Agriculture, v.13, e550, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13030550

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13030550 -

Lessa, C. I. N.; Sousa, G. G.; Sousa, H. C.; Silva Junior, F. B. S.; Sousa, J. T. M.; Lacerda, C. F. Influência da cobertura morta vegetal e da salinidade sobre as trocas gasosas de genótipos de amendoim. Revista Brasileira de Agricultura Irrigada , v.15, p.88-96. 2021. https://doi.org/10.7127/rbai.v1501203

» https://doi.org/10.7127/rbai.v1501203 -

Lima, G. S.; Pinheiro, F. W. A.; Gheyi, H. R.; Soares, L. A. A.; Sousa, P. F. N.; Fernandes, P. D. Saline water irrigation strategies and potassium fertilization on physiology and fruit production of yellow passion fruit. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental , v.26, p.180-189, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v26n3p180-189

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v26n3p180-189 -

Oliveira, G. S.; Viana, T. V. A.; Sousa, G. G.; Santos, S. O.; Costa, F. H. R.; Silva, A. G.; Pereira, A. P. A.; Lopes, F. B.; Goes, G. F.; Leite, K. N. Phosphate fertilization, biofertilizer and Bacillus sp. in peanut cultivation under salt stress. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental . v.28, e279003, 2024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v28n4e279003

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v28n4e279003 -

Queiroz, G. C. M. de; Medeiros, J. F. de; Silva, R. R. da; Morais, F. M. da S.; Sousa, L. V. de; Soza, M. V. P. de; Santos, E. da N.; Ferreira, F. N.; Silva, J. M. C. da; Clemente, M. I. B.; Granjeiro, J. C. de C.; Sales, M. N. de A.; Constante, D. C.; Nobre, R. G.; Sá, F. V. da S. Growth, solute accumulation, and ion distribution in sweet sorghum under salt and drought stresses in a Brazilian potiguar semiarid area. Agriculture, v.13, e803, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13040803

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13040803 - Richards, L. A. Diagnosis and improvement of saline and alkali soils. Washington: US Department of Agriculture, 1954. 160p.

-

Santos, A. A. C.; Oliveira, A. J.; Oliveira, T. C.; Cruz, A. K. N.; Almici, M. S. A cultura do Arachis hypogea L.: Uma revisão. Research, Society and Development, v.10, e24910212719, 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v10i2.12719

» http://dx.doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v10i2.12719 -

Santos, R. C. dos; Moreira, J. de A. N.; Valle, L. V.; Freire, R. M. M.; Almeida, R. P. de; Araújo, J. M. de; Silva, L. C. Amendoim BR-1: informações para o seu cultivo. Campina Grande: Embrapa Algodão, 2009. 4p. Available: <Available: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/bitstream/doc/578979/1/FolderAmendoimBR14ed.pdf >. Accessed on: Apr. 2025

» https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/bitstream/doc/578979/1/FolderAmendoimBR14ed.pdf -

Semedo, T. da C. M.; Sousa, G. G.; Sousa, H. C.; Schneider, F.; Lima, J. M. dos P.; Gomes, K. R.; Simplicio, A. A. F.; Saraiva, K. R. Production and fruit quality of Italian zucchini under brackish water irrigation strategies. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental , v.28, e277139, 2024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v25n1p3-9

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v25n1p3-9 -

Silva, F. A. S.; Azevedo, C. A. V. The Assistat software version 7.7 and its use in the analysis of experimental data. African Journal of Agricultural Research, v.11, p.3733-3740, 2016. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2016.11522

» https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2016.11522 -

Sousa, H. C.; Sousa, G. G.; Viana, T. V. A.; Pereira, A. P. A.; Lessa, C. I. N.; Souza, M. V. P.; Guilherme, J. M. S.; Goes, G. F; Alves, F. G. S.; Gomes, S. P.; Silva, F. D. B. Bacillus aryabhattai mitigates the effects of salt and water stress on the agronomic performance of maize under an agroecological system. Agriculture, v.13, e1150, 2023b. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13061150

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13061150 -

Sousa, H. C.; Viana, T. V. de A.; Sousa, G. G.; Azevedo, B. M. de; Lessa, C. I. N.; Freire, M. H. da C.; Goes, G. F.; Balde, B. Productivity in the peanut under salt stress in soil with a cover of plant mulch. Revista Ciência Agronômica, v.54, e20228513, 2023a. https://doi.org/10.5935/1806-6690.20230043

» https://doi.org/10.5935/1806-6690.20230043 -

Souto, A. G. de L.; Cavalcante, L. F.; Melo, E. N.; Cavalcante, Í. H. L.; Oliveira, C. J. A.; Silva, R. I. L.; Mesquita, E. F.; Mendonça, R. M. N. Gas exchange and yield of grafted yellow passion fruit under salt stress and plastic mulching. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental . v.26, p.823-830, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v26n11p823-830

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v26n11p823-830 - Taiz, L.; Zeiger, E.; Moller, I. M.; Murphy, A. Fisiologia e desenvolvimento vegetal. 6.ed. Porto Alegre: ARTEMED, 2017. 858p.

Data availability

This research does not include any supplementary data.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

25 Aug 2025 -

Date of issue

Dec 2025

History

-

Received

31 Dec 2024 -

Accepted

01 June 2025 -

Published

07 July 2025

Leaf gas exchange and production of peanut under brackish water irrigation strategies

Leaf gas exchange and production of peanut under brackish water irrigation strategies

VEG - Vegetative phase (0 - 14 days after sowing - DAS); FLO - Flowering phase (15 - 29 DAS); G.F - Gynophore formation phase (30 - 36 DAS); P.F - Pod formation phase (37 - 47 DAS); P.M - Pod maturation (47 - 80 DAS)

VEG - Vegetative phase (0 - 14 days after sowing - DAS); FLO - Flowering phase (15 - 29 DAS); G.F - Gynophore formation phase (30 - 36 DAS); P.F - Pod formation phase (37 - 47 DAS); P.M - Pod maturation (47 - 80 DAS)

VEG - Vegetative phase (0 - 14 days after sowing - DAS); FLO - Flowering phase (15 - 29 DAS); G.F - Gynophore formation phase (30 - 36 DAS); P.M - Pod maturation (37 - 80 DAS)

VEG - Vegetative phase (0 - 14 days after sowing - DAS); FLO - Flowering phase (15 - 29 DAS); G.F - Gynophore formation phase (30 - 36 DAS); P.M - Pod maturation (37 - 80 DAS)

S1 - Use of low-salinity water (W1 = 0.8 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S2 - Use of high-salinity water (W2 = 4.0 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S3 - Use of W2 only in the flowering and pod formation phases; S4 - Use of W2 only in the vegetative and gynophore formation phases; S5 - Use of W2 in the gynophore formation phase; S6 - Use of W2 in the vegetative and flowering phases; S7 - Use of W2 in the pod formation phase; S8 - Use of W2 in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases. Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 6).

S1 - Use of low-salinity water (W1 = 0.8 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S2 - Use of high-salinity water (W2 = 4.0 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S3 - Use of W2 only in the flowering and pod formation phases; S4 - Use of W2 only in the vegetative and gynophore formation phases; S5 - Use of W2 in the gynophore formation phase; S6 - Use of W2 in the vegetative and flowering phases; S7 - Use of W2 in the pod formation phase; S8 - Use of W2 in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases. Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 6).

S1 - Use of low-salinity water (W1 = 0.8 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S2 - Use of high-salinity water (W2 = 4.0 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S3 - Use of W2 only in the flowering and pod formation phases; S4 - Use of W2 only in the vegetative and gynophore formation phases; S5 - Use of W2 in the gynophore formation phase; S6 - Use of W2 in the vegetative and flowering phases; S7 - Use of W2 in the pod formation phase; S8 - Use of W2 in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases. Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 6).

S1 - Use of low-salinity water (W1 = 0.8 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S2 - Use of high-salinity water (W2 = 4.0 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S3 - Use of W2 only in the flowering and pod formation phases; S4 - Use of W2 only in the vegetative and gynophore formation phases; S5 - Use of W2 in the gynophore formation phase; S6 - Use of W2 in the vegetative and flowering phases; S7 - Use of W2 in the pod formation phase; S8 - Use of W2 in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases. Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 6).

S1 - Use of low-salinity water (W1 = 0.8 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S2 - Use of high-salinity water (W2 = 4.0 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S3 - Use of W2 only in the flowering and pod formation phases; S4 - Use of W2 only in the vegetative and gynophore formation phases; S5 - Use of W2 in the gynophore formation phase; S6 - Use of W2 in the vegetative and flowering phases; S7 - Use of W2 in the pod formation phase; S8 - Use of W2 in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases. Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 6).

S1 - Use of low-salinity water (W1 = 0.8 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S2 - Use of high-salinity water (W2 = 4.0 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S3 - Use of W2 only in the flowering and pod formation phases; S4 - Use of W2 only in the vegetative and gynophore formation phases; S5 - Use of W2 in the gynophore formation phase; S6 - Use of W2 in the vegetative and flowering phases; S7 - Use of W2 in the pod formation phase; S8 - Use of W2 in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases. Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 6).

S1 - Use of low-salinity water (W1 = 0.8 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S2 - Use of high-salinity water (W2 = 4.0 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S3 - Use of W2 only in the flowering and pod formation phases; S4 - Use of W2 only in the vegetative and gynophore formation phases; S5 - Use of W2 in the gynophore formation phase; S6 - Use of W2 in the vegetative and flowering phases; S7 - Use of W2 in the pod formation phase; S8 - Use of W2 in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases. Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 6).

S1 - Use of low-salinity water (W1 = 0.8 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S2 - Use of high-salinity water (W2 = 4.0 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S3 - Use of W2 only in the flowering and pod formation phases; S4 - Use of W2 only in the vegetative and gynophore formation phases; S5 - Use of W2 in the gynophore formation phase; S6 - Use of W2 in the vegetative and flowering phases; S7 - Use of W2 in the pod formation phase; S8 - Use of W2 in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases. Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 6).

S1 - Use of low-salinity water (W1 = 0.8 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S2 - Use of high-salinity water (W2 = 4.0 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S3 - Use of W2 only in the flowering and pod formation phases; S4 - Use of W2 only in the vegetative and gynophore formation phases; S5 - Use of W2 in the gynophore formation phase; S6 - Use of W2 in the vegetative and flowering phases; S7 - Use of W2 in the pod formation phase; S8 - Use of W2 in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases. Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 6)

S1 - Use of low-salinity water (W1 = 0.8 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S2 - Use of high-salinity water (W2 = 4.0 dS m-1) throughout the crop cycle; S3 - Use of W2 only in the flowering and pod formation phases; S4 - Use of W2 only in the vegetative and gynophore formation phases; S5 - Use of W2 in the gynophore formation phase; S6 - Use of W2 in the vegetative and flowering phases; S7 - Use of W2 in the pod formation phase; S8 - Use of W2 in the vegetative, flowering and gynophore formation phases. Means followed by different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 6)