ABSTRACT

Using water with high salt concentrations in irrigated agriculture can affect sensitive plants’ metabolic and biochemical functions. Therefore, strategies are needed to minimize the adverse impacts of salt stress. This study aimed to evaluate radish plant growth, water relations, and biochemical and nutritional responses as a function of irrigation water salinity and exogenous ascorbic acid (AsA) application. The experiment was conducted in a controlled greenhouse under a completely randomized design in a 3 × 2 factorial scheme with four replicates, using one plant per experimental unit. Treatments consisted of three levels of irrigation water salinity (0.5, 3.0, and 5.0 dS m-1) and ascorbic acid application [without (0 mM) and with (1 mM)]. Increased salinity (3.0 and 5.0 dS m-1) affected growth, water status, biochemical traits, and nutrient accumulation in radish plants. Stem diameter (55.0%), shoot mass ratio (14.5%), relative growth rate (9.0%), and soluble sugars in shoot (29.8%) and root (47.6%) increased with 1 mM AsA application, especially at 5.0 dS m-1. Applying 1 mM AsA reduced Na⁺ and Cl⁻ cont 0ents in both shoot and root at all salinity levels and increased the Mg²⁺ content in shoot and root and Ca²⁺ content at 3.0 and 5.0 dS m-1.

Key words:

Raphanus sativus L.; abiotic stresses; salt stress; mitigating

HIGHLIGHTS:

The attenuating effect of ascorbic acid is dose-dependent on the concentration of salts in the irrigation water.

Ascorbic acid with a concentration of 1 mM improved growth and sugars under a 5.0 dS m-1 salinity.

Ascorbic acid reduced Na+ and Cl- and increased Mg²+ and Ca²+ in roots and shoots under salinity.

RESUMO

O uso de água com altas concentrações de sais no manejo da agricultura irrigada pode afetar funções metabólicas e bioquímicas de plantas sensíveis. Diante disso, torna-se necessário adotar estratégias que minimizem os impactos adversos do estresse salino. Objetivou-se, com este estudo, avaliar o crescimento, as relações hídricas, bioquímicas e nutricionais de plantas de rabanete em função da salinidade da água de irrigação e da aplicação exógena de ácido ascórbico (AsA). O experimento foi conduzido em casa de vegetação sob delineamento inteiramente casualizado, em esquema fatorial 3 × 2, com quatro repetições e uma planta por parcela experimental. Os tratamentos consistiram em três níveis de salinidade da água de irrigação (0,5; 3,0 e 5,0 dS m-1) e aplicação de AsA [sem (0 mM) e com (1 mM)]. O aumento da salinidade (3,0 e 5,0 dS m-1) afetou variáveis de crescimento, relações hídricas, bioquímicas e nutricionais do rabanete. A aplicação de 1 mM de AsA promoveu incrementos no diâmetro do caule (55,0%), razão da massa da parte aérea (14,5%), taxa de crescimento relativo (9,0%) e teores de açúcares solúveis na parte aérea (29,8%) e na raiz (47,6%), especialmente em 5,0 dS m-1. Além disso, o AsA mitigou os teores de Na⁺ e Cl⁻ na parte aérea e raiz em todos os níveis salinos, e aumentou os teores de Mg²⁺ na parte aérea e raiz e de Ca²⁺ na parte aérea nas salinidades de 3,0 e 5,0 dS m-1.

Palavras-chave:

Raphanus sativus L.; estresses abióticos; estresse salino; atenuante

Introduction

Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) is a valuable root vegetable due to its medicinal properties, high nutritional value, and antioxidant action (Amin, 2023). Cultivated mainly in small areas, it relies on frequent irrigation, often with low-quality water (Putti et al., 2022). Its rusticity, short cycle, and early harvest make it popular among small and medium-sized farmers, ensuring quick financial returns (Dias et al., 2022).

Although rustic, radish is moderately sensitive to soil salinity (Amin, 2023). High salt concentrations in irrigation water disrupt metabolic functions, inhibiting germination, reducing root and shoot growth, and decreasing yield (Liang et al., 2018).

Ascorbic acid (AsA) application is a promising strategy to mitigate salinity effects (Mishra et al., 2024). In plants, AsA participates in non-enzymatic antioxidant metabolism, and its application reduces oxidative stress, limits lipid peroxidation, and enhances nutrient uptake, benefiting radish growth under water deficit (Henschel et al., 2023). Additionally, AsA regulates photosynthetic enzymes and boosts antioxidant biosynthesis, neutralizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and improving plant tolerance to salt stress (El-Beltagi et al., 2022).

Studies have shown that AsA enhances growth, yield, and abiotic stress tolerance in crops such as bell pepper, okra seedlings, and tomatoes (Wang et al., 2019; Alayafi, 2020; El-Beltagi et al., 2022). Despite this, the specific effects of AsA application on the growth, metabolism, and production of radish crops irrigated with saline water have been little explored.

In view of the above, it is hypothesized that ascorbic acid concentrations improve the growth, physiological, and nutritional aspects of radish plants under saline conditions. Thus, the aim of this research was to evaluate the growth, water, biochemical, and nutritional relationships of radish plants as a function of water salinity and under exogenous application of ascorbic acid.

Material and Methods

The experiment was carried out between October and November 2023 in a greenhouse belonging to the Department of Agrarian and Forestry Sciences of the Federal Rural University of the Semi-Arid (UFERSA), Mossoró city, Rio Grande do Norte state, Brazil (5° 12’ S, 37° 19’ W and altitude of 20 m). The climate of the region is characterized as BSh, hot and dry (Alvares et al., 2013). Mean air temperature and relative air humidity data were collected using a digital thermo-hygrometer (Figure 1).

The experiment followed a completely randomized design in a 3 × 2 factorial scheme with four replicates. The first factor was the salinity levels of the irrigation water (0.5, 3.0, and 5.0 dS m-1), while the second factor was the application of ascorbic acid [without (0.0 mM) and with (1.0 mM)]. Each experimental unit consisted of one plant per pot, totaling 24 experimental units. The irrigation water electrical conductivity levels of 0.5, 3.0 and 5.0 dS m-1 were considered low, moderate and high levels, respectively, according to Ribeiro et al. (2024). The AsA concentrations (0 and 1.0 mM) were based on research by Basílio et al. (2018).

Radish plant variety Crimson Gigante was sown in 2.6 dm3 pots containing a mixture of sieved soil and organic compost in a 3:1 (v/v) ratio, respectively (Table 1). At 7 days after sowing (DAS), thinning was performed, leaving one plant per pot. At 13 DAS, with the appearance of the first pair of leaves, the application of the treatments began. The saline solutions were prepared for a volume of 60 dm3 by adding sodium chloride (NaCl) to water, except for the level of 0.5 dS m-1, prepared from the local-supply water. The electrical conductivity of the irrigation water was monitored every 5 days to check each salt concentration, using a portable conductivity meter (model CD-880, Instrutherm).

The AsA solution was prepared at the time of each application. The AsA concentrations were prepared by dissolution in distilled water, and spraying was carried out on the shoots of the plants with a portable manual sprayer. During the application, the plants were isolated to prevent contamination. In the AsA solutions, Tween-80 (0.05% v/v), a solubilizing surfactant, was added to increase the substance’s adhesion to the leaf. An average of 20 mL of solution was applied per plant. At 13 DAS, ascorbic acid applications were initiated, with weekly applications totaling three (13, 20, and 27 DAS).

At 34 DAS, the following growth variables were measured: plant height, measured with the aid of a ruler graduated in centimeters (cm); stem diameter, measured with a digital caliper in millimeters (mm); and the number of leaves, counted manually. Then, the plants were collected and taken to the Laboratory of Reception and Preparation of Samples, belonging to the Center for Plant Research of the Semi-Arid Region, for further analysis.

After that, the plants were separated into shoots and roots and then weighed on an analytical scale (0.001 g) to obtain the fresh weight of the shoots (SFW), root (RFW) and total (TFW). With the fresh mass values, the shoot mass ratio (SMR), root mass ratio (RMR), shoot-root ratio, and relative growth rate (RGR) were also obtained. Root length (RL) and root diameter (RD) were also evaluated with the aid of a digital caliper (mm).

The relative water content (RWC) was determined according to Irigoyen et al. (1992) with adaptations. Leaf discs (6 mm²) were collected from the central vein of the leaves to measure fresh mass (FMD), then immersed in distilled water for 4 hours. After gently drying with paper towels, the turgid mass (TMD) was recorded. The discs were then oven-dried at 80 °C for 24 hours to obtain the dry mass (DMD). RWC was calculated using Eq. 1.

where:

FMD - fresh mass of discs (g),

DMD - dry mass of discs (g); and,

TMD - turgid mass of discs (g).

With adaptations, electrolyte leakage (EL) was determined following Lutts et al. (1996). After three washes with distilled water (3 min each), ten leaf discs were immersed in 25 mL of deionized water in Falcon tubes, and the initial electrical conductivity (EC) was measured after 90 min (EC1). The tubes were then heated at 85 °C for 1 hour, cooled to 25 °C, and the final EC was recorded (EC2). EL was calculated using Eq. 2.

where:

EC1 - initial EC reading; and,

EC2 - final EC reading.

Subsequently, the plant material was taken to a forced circulation oven at 65 ºC and kept until it reached constant weight. With the dried materials, the dry weights of the shoot (SDW), root (RDW) and total (TDW) were obtained on an analytical scale (0.001 g). Then, the samples were crushed in a portable mill to perform the biochemical and nutritional analyses of the shoots and roots.

Biochemical analyses of total soluble sugars (TSS) and reducing sugars (RS) were performed using the phenol-sulfuric acid method (Dubois et al., 1956) and the dinitrosalicylic acid reagent (Miller, 1959). For TSS, 50 mg of lyophilized tissue was extracted with 5 mL of distilled water, incubated at 100 °C for 30 min, and then centrifuged at 1000 rpm. The supernatant (100 µL) was mixed with 400 µL of water, 0.5 mL of 5% phenol, and 2.5 mL of H2SO4. After vortexing, the absorbance was measured at 490 nm after 20 min. The concentration of soluble proteins was determined using the Bradford reagent (Bradford et al., 1976), and proline was determined by the acid ninhydrin method (Bates et al., 1973).

The plant material used in the nutritional analyses was collected at the end of the experiment. It consisted of the entire vegetative biomass rather than only diagnostic leaves. This material was thoroughly dried and finely ground using a knife mill before analysis. The nutritional contents of K⁺, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, and Cl⁻ were determined by digestion in nitric acid. K⁺ and Na⁺ were determined by flame spectrometry, while Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ were determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (Chapman & Pratt, 1962); Cl⁻ was determined by the Mohr method, extracted by calcium nitrate solution (Ca(NO₃)₂·4H₂O), in the form of chloride ion, titrated with a standardized silver nitrate solution (AgNO₃), in the presence of potassium dichromate (K₂CrO₄) as an indicator.

All data were analyzed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and homoscedasticity using the Levene test. The data were subjected to analysis of variance (F test), and in cases of significance, Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05) was used to compare the means. The analyses were conducted using the SISVAR software (Ferreira, 2019). Pearson’s correlation analysis and principal component analysis (PCA) were performed for joint interpretation between treatments and variables using the R software (R Core Team, 2023).

Results and Discussion

The summary of the analysis of variance is presented in Table 2. A significant interaction between salinity and ascorbic acid was observed for the growth variables SMR, and RMR. Salinity independently influenced PH, SD, NL, RL, and RD, while AsA affected RD and RGR. The S × AsA interaction was significant for the biochemical variables TSS and TSR. The S factor influenced reducing sugars in the shoot (RSS), reducing sugars in the root (RSR), protein content in the root (PR), proline content in the shoot (PLS), proline content in the root (PLR), RWC, and EL, while AsA affected RSS and RSR. Regarding nutritional variables, the S × AsA interaction had effects on NaS, KS, CaS, MgS, ClS, NaR, KR, MgR, and ClR, with an individual effect of S on CaR.

The overall effects of reduced growth on radish plants were observed with increasing salinity levels in irrigation water (Figures 2A-E). It was observed that the height of the plants was reduced with increasing doses of salt; however, with the application of AsA, no significant differences were observed in the salinity treatment (Figure 2A). Stem diameter (SD) was also affected by the increase in salinity, with significant reductions being observed (Figure 2B). The number of leaves was reduced by the increase in salinity (Figure 2C), regardless of the application of AsA; as the salinity increased from 3.0 to 5.0 dS m-1, the number of leaves was reduced between 17.24 and 44.82%, respectively, compared to the control (0.5 dS m-1). For root length (Figure 2D) and diameter (Figure 2E), the same behavior was observed for all salinity levels, where the increase in salinity led to reductions of 45.74 and 45.97%, respectively, in root length and diameter, at the level of 5.0 dS m-1, when compared to the salinity of 0.5 dS m-1.

Plant height (A), stem diameter (B), number of leaves (C), root length (D) and root diameter (E) of radish plants subjected to different levels of electrical conductivity in irrigation water

The lack of significant effect of exogenous application of AsA on plant height, stem diameter, number of leaves, and root length can be attributed to the intensity of salt stress at the levels tested, which may have exceeded the ability of AsA to mitigate damage. Under high salinity conditions, excessive accumulation of toxic ions, such as Na⁺ and Cl⁻, compromises essential physiological processes, such as water and nutrient absorption, directly affecting plant growth and development (Akram et al., 2017). In addition, AsA may have been translocated to other metabolic processes, putting it at the expense of plant tolerance to salinity (Hasanuzzaman et al., 2020). It is worth mentioning that, under extreme salinity conditions, although important, antioxidant mechanisms are insufficient to compensate for damage to essential physiological processes, such as water and nutrient absorption, and root growth can be heavily impaired (Shabala & Munns, 2017). On the other hand, the diameters of the stem and roots were positively influenced at salinity levels 5.0 and 0.5 dS m-1, respectively, since AsA plays an important role in reducing oxidative damage caused by salt stress, helping to neutralize free radicals and promoting the recovery of plant cells (Hasanuzzaman et al., 2020).

In the case of fresh matter, the shoot was influenced only by salinity (Figure 3A). As salinity levels increased, the fresh mass of radish plants was reduced regardless of the application of AsA (Figure 3A).

Shoot fresh weight - SFW (A), root fresh weight - RFW (B), shoot dry weight - SDW (C), root dry weight - RDW (D) and total dry weight - TDW (E) of radish plants subjected to different levels of electrical conductivity in irrigation water

However, a gain of 63% in fresh matter was observed in the treatment that did not receive the application of AsA for the salinity level of 0.5, compared to the 5.0 dS m-1 level. In the root, the fresh weight was gradually reduced with the increase in salinity, not influenced by the application of AsA (Figure 3B). However, about the root dry matter, the salinity level of 5.0 dS m-1 drastically reduced the dry weight, leading to a 65% reduction without AsA and when compared to the salinity level of 0.5 dS m-1 (Figure 3C). Regarding total dry matter, plants under salinity of 5.0 dS m-1 showed a significant reduction in total weight, equal to 50.94% in plants without AsA and compared to the control (0.5 dS m-1) (Figure 3D). Shoot dry matter was not influenced by the application of saline water and AsA.

These results demonstrate that the accumulation of salts in the soil and root zone interferes with the ion balance and increases the production of reactive oxygen species, which oxidize molecules and cause damage to plant tissues. This imbalance also affects the translocation of nutrients and the metabolism of carbohydrates, resulting in lower growth and yield due to decreases in biomass (Hernández-Herrera et al., 2022; Balasubramaniam et al., 2023).

Regarding the proportions of shoot and root dry weight ratio (Figures 4A and B), it was observed that, under the salinity of 5.0 dS m-1, the application of ascorbic acid increased the proportion of shoot in the whole plant, compared to the other treatments with salinity (Figure 4A).

Shoot mass ratio - SMS (A), root mass ratio - RMR (B), shoot/tuber ratio - STR (C) and relative growth rate - RGR (D) of radish plants subjected to different levels of electrical conductivity in irrigation water and under exogenous application of ascorbic acid

Furthermore, in proportional terms, the application of AsA led to a lower root fraction in plants under higher salinity (Figure 4B). These values show that the increase in salinity compromised root growth more severely than shoot growth, verified by higher values of shoot-root ratio (Figure 4C). The relative growth rate (RGR) was reduced more strongly in plants under high salinity (5.0 dS m-1), and the application of AsA increased the growth rate by 9.06% in the treatment without AsA (Figure 4D).

Salinity impairs all essential processes, such as photosynthesis, protein synthesis, growth, and biomass production (Adhikari et al., 2020). However, the exogenous application of AsA favored an increase in growth and biomass, given that its application increases cell division and enlargement (Hassan et al., 2021), which affects the morphological variables SMR, RMR, and RGR.

There was significant interaction for total sugars (TS), while reducing sugars (RS) showed only an individual effect of the factors in radish subjected to salinity and application of ascorbic acid (Figure 5). The TS content was affected by the salinity in the shoot and roots; however, at the salinity level of 5.0 dS m-1, the application of AsA promoted increments of 29.83 and 47.60%, respectively, in shoots and roots, compared to the treatment that did not receive the application of AsA (Figure 5A). For the RS content, the increase in salinity caused reductions in its content of 12.5 and 27.7%, respectively, in the shoots and roots, at the salinity level of 0.5 dS m-1 and when compared to the salinity level of 0.5 dS m-1 (Figure 5B). Furthermore, the exogenous application of AsA (1 mM) promoted an increase of 11.76% in the RS content compared to the concentration of 0 mM (Figure 5B).

Total sugars - TS (A) and reducing sugars - RS (B) of the shoot and root parts of radish plants subjected to different levels of electrical conductivity in irrigation water and under exogenous application of ascorbic acid

The observed increases in sugars may be due to the activation of carbohydrate-synthesizing enzymes caused by the application of AsA and salicylic acid, which increase the accumulation of these macromolecules, and also by the hydrolysis of polysaccharides (Dawood et al., 2022). In addition, soluble sugars are important in signaling nutrients, osmoprotectants, and metabolites involved in diverse responses to abiotic stresses (Afzal et al., 2021).

Different effects were observed on proteins and proline levels in shoots and roots (Figure 6). In the shoot, salinity and AsA application had no effect on total protein content. On the other hand, there was a significant reduction in proteins in the roots, especially under the salinity level of 5.0 dS m-1, showing a reduction of 36.02% compared to the salinity level of 0.5 dS m-1.

Proteins (A) and proline (B) of the shoot and root parts of radish plants subjected to different levels of electrical conductivity in irrigation water

This reduction is due to the proteolysis of this macromolecule, changes in the protein structure, and disintegration of peptide chains (Perveen & Hussain, 2021). Salinity also induces the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, enzyme inactivation, DNA changes, and interaction with essential constituents of plant cells (Shafiq et al., 2020).

It is notorious that the increase in salinity (3.0 to 5.0 dS m-1) increased the accumulation of proline in both the shoot and the roots (Figure 6B). No effect of AsA application was observed for the proline content in both plant parts. The increase in this stress-related amino acid is because proline is a compatible solute that helps in osmotic balance, making plants withstand adverse conditions; in addition, proline mediates stress signaling, eliminating ROS and maintaining the osmolarity of cells under stressful conditions (Elkelish et al., 2020).

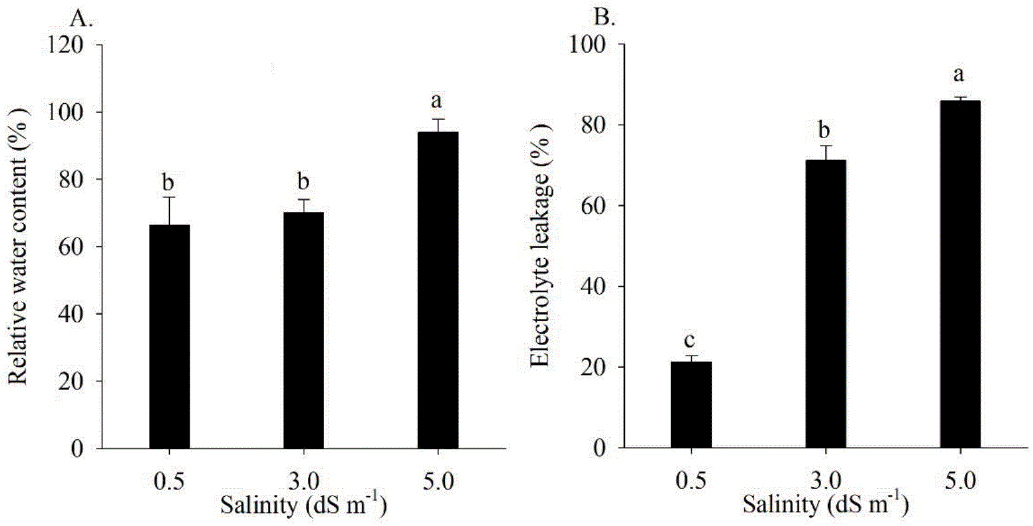

The relative water content (RWC) and electrolyte leakage were influenced only by salinity (Figures 7A and B). At the 5.0 dS m-1 level, the RWC showed a reduction of 28.80% compared to the level of 0.5 dS m-1 (Figure 7A). In contrast, the electrolyte leakage showed membrane damage of 70.49 and 74.22%, respectively, at salinity levels of 3.0 and 5.0 dS m-1 compared to the level of 0.5 dS m-1 (Figure 7B).

Relative water content - RWC (A) and electrolyte leakage - EL (B) of radish plants subjected to different levels of electrical conductivity in irrigation water

It is known that salinity drastically affects plant-water relationships, as there is a reduction in soil water availability, impairing the overall water content in the plant (Singh et al., 2022). Singh et al. (2022) also mention that electrolyte leakage is induced by stress, causing increased lipid peroxidation, plasma membrane rupture, and the release of essential ions and compatible solutes.

The nutritional composition of the shoots and roots of radish plants cultivated under different salinity levels and AsA application showed a significant interaction between the factors salinity and AsA concentrations for all elements analyzed (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl-) (Table 3).

In the shoot, Na+ and Cl- contents were increased with salinity severity, showing increases of 35.38 and 44.88% (Na+) and 57.96 and 69.47% (Cl-), respectively, for the salinity levels 3.0 and 5.0 dS m-1, compared to the salinity level of 0.5 dS m-1. However, the application of AsA led to significant reductions to the ions mentioned, with decreases of 33.96 and 28.17% (Na+), respectively, at salinity levels of 3.0 and 5.0 dS m-1 and 15.32, 21.35 and 2.41% (Cl-), respectively, at salinity levels of 0.5, 3.0 and 5.0 dS m-1, and both in comparison to the treatment that did not receive the application of AsA (Table 3).

K+ content in the shoot was reduced with the increase in salinity; the application of AsA did not influence this nutrient. On the other hand, Ca2+ and Mg2+ contents increased in the shoot as the salinity levels intensified, and there were increases in their contents of 8.23, 5.41 and 23.15% (Ca2+) and 41.17, 49.04 and 28.20% (Mg2+) with the exogenous application of AsA, all for the salinity levels 0.5, 3.0 and 5.0 dS m-1, respectively (Table 3).

In the roots, the contents of Na⁺ and Cl⁻ increased with the intensification of salinity, showing increases of 42.22 and 74.35% (Na⁺) and 57.94 and 72.20% (Cl⁻), respectively, for the salinity levels of 3.0 and 5.0 dS m-1, compared to the level of 0.5 dS m-1 (Table 3). On the other hand, the increase in salinity levels reduced the K⁺ and Ca²⁺ contents up to the level of 3.0 dS m-1, with decreases of 57.58 and 32.14%, respectively, when comparing the levels of 0.5 and 3.0 dS m-1 (Table 3). The exogenous application of AsA did not influence the root contents of Na⁺, Cl⁻, K⁺ and Ca². However, the application of AsA promoted significant increases in the content of Mg²⁺ as the salinity levels increased, with increases of 6.13, 17.82 and 33.16%, respectively, for the levels of 0.5, 3.0 and 5.0 dS m-1.

In general, high concentrations of Na+ and Cl- in the soil reduce the activities of nutrient ions; with this, there is an increase in salinity, causing osmotic stress in cultivated plants, reduction in water availability, stress and changes in cellular ionic balance, as well as deficiency and toxicity of some nutrients, but in addition, the increase in salinity causes a reduction in the absorption of N , P, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ (Ehtaiwesh et al., 2022). Hassan et al. (2021) mention that applying AsA reduces the Na+ content and increases K+ and Ca+ contents in plants in soils subjected to salinity. In addition, the plant’s water absorption is limited when there is an increase in ions, putting nutrient absorption at the expense (Caetano et al., 2024); in addition, the accumulation of Na+ impairs the absorption of K+ around plant roots due to the similar chemical properties of these ions (Kumari et al., 2021).

The Na+ content showed moderate negative correlations with NL (-0.76), RL (-0.75), RD (-0.77), RFW (-0.76) and TFW (-0.79), as well as strong negative correlations with PH (-0.85), SD (-0.87), SFW (-0.85), RDW (-087) and SDW (-0.87) for the shoot of the radish (Figure 8). Regarding the root part, Na+ showed negative correlations from strong to very strong that ranged from -0.82 to -0.96, with RFW and RGR, respectively. On the other hand, the Cl- content showed negative correlations from strong to very strong with the growth variables (PH, SD, NL, RL, RD, RFW, SFW, TFW, RDW, SDW, TDW and RGR), with variations from -0.80 to -0.97 for the shoot and from -0.88 to -0.97 for the root part. In addition, the growth variables mentioned showed negative correlations ranging from moderate to very strong with RWC (-0.75 to -0.95) and EL (-0.73 to -0.98).

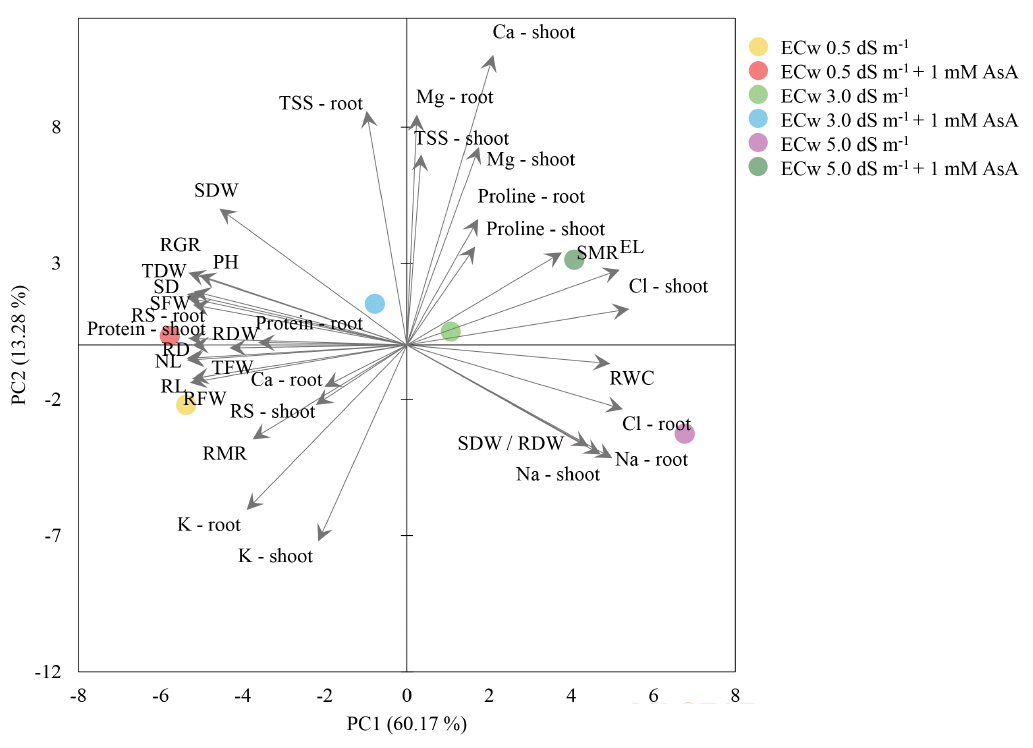

The sum of the principal components (PC), PC1 and PC2, contributed with 73.45% of the total variability (Figure 9). PC1 resulted in 60.17% of the total variability and obtained positive correlations with Ca - shoot, Mg2+ (shoot and root), Cl- (shoot and root), Na+ (shoot and root), EL, RWC, SDW/RDW and Proline (shoot - root), mainly for ECw 3.0 dS m-1, ECw 5.0 dS m-1 and ECw 5.0 dS m-1 + 1 mM AsA. PC2 resulted in 13.28% of the total variability and obtained negative correlations with the growth variables (PH, SD, NL, RL, RD, SFW, RFW, TFW, SDW, RDW, TDW, SDW/RDW, RGR), Ca-root, K+ (shoot and root), Protein (shoot and root), RS (shoot and root) and TSS (shoot and root), essentially for ECw 0.5 dS m-1 and ECw 0.5 dS m-1 + 1 mM AsA treatments. Thus, it can be stated that the highest salinity in the irrigation water (ECw 5.0 dS m-1) resulted in the highest concentration of salts, such as Na+ and Cl-, which negatively influenced the biometric and biochemical variables related to PC2.

Conclusions

-

The increase in salinity (3.0 and 5.0 dS m-1) affected the growth variables and water, biochemical, and nutritional relationships of radish plants.

-

Plant height, stem diameter, shoot mass ratio, shoot and root ratio, relative growth rate and soluble sugars were increased with exogenous application of ascorbic acid (1 mM), mainly at the salinity level of 5.0 dS m-1.

-

Applying 1 mM of ascorbic acid reduced Na+ and Cl- contents in the shoots and roots at all salinity levels and increased the contents of Mg2+ (shoot and root) and Ca2+ (shoot) at the tested salinity levels of 3.0 and 5.0 dS m-1.

Literature Cited

-

Adhikari, B.; Dhungana, S. K.; Kim, I. D.; Shin, D. H. Effect of foliar application of potassium fertilizers on soybean plants under salinity stress. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences, v.19, p.261-269, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2019.02.001

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2019.02.001 - Afzal, S.; Chaudhary, N.; Singh, N. K. Role of soluble sugars in metabolism and sensing under abiotic stress. In: Aftab, T.; Hakeem, K. R. (eds). Plant Growth Regulators: signalling under stress conditions. Springer, Cham, 2021. Cap.14, p.305-334.

-

Akram, N. A.; Shafiq, F.; Ashraf, M. Ascorbic acid - a potential oxidant scavenger and its role in plant development and abiotic stress tolerance. Frontiers in Plant Science, v.8, e613, 2017. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00613

» https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00613 -

Alayafi, A. A. M. Exogenous ascorbic acid induces systemic heat stress tolerance in tomato seedlings: transcriptional regulation mechanism. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, v.27, p.19186-19199, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-06195-7

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-06195-7 -

Alvares, C. A.; Stape, J. L.; Sentelhas, P. C.; Gonçalves, J. L. M.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorologische Zeitschrift, v.22, p.711-728, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1127/0941-2948/2013/0507

» https://doi.org/10.1127/0941-2948/2013/0507 -

Amin, A. E. E. A. Z. Effects of saline water on soil properties and red radish growth in saline soil as a function of co-applying wood chips biochar with chemical fertilizers. BMC Plant Biology, v.23, e382, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-023-04397-3

» https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-023-04397-3 -

Balasubramaniam, T.; Shen, G.; Esmaeili, N.; Zhang, H. Plants response mechanisms to salinity stress. Plants, v.12. e2253, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12122253

» https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12122253 -

Bates, L. S.; Waldren, R. P. A.; Teare, I. D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant and Soil, v.39, p.205-207, 1973. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00018060

» https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00018060 -

Basílio, A. G. S.; Sousa, L. V.; Silva, T. I.; Moura, J. G.; Gonçalves, A. C. M.; Melo Filho, J. S.; Leal, Y. H.; Dias, T. J. Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) morphophysiology under salinity stress and ascorbic acid treatments. Agronomía Colombiana, v.36, p.257-265, 2018. https://doi.org/10.15446/agron.colomb.v36n3.74149

» https://doi.org/10.15446/agron.colomb.v36n3.74149 -

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry, v.72, p.248-254, 1976. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3

» https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 -

Caetano, E. J. M.; Silva, A. A. R.; Lima, G. S. de.; Azevedo, C. A. V. de.; Veloso, L. L. de S. A.; Arruda, T. F. de L.; Souza, A. R. de; Soares, L. A. dos A.; Gheyi, H. R.; Dias, M. dos S.; Borborema, L. D. A.; Sousa, V. D. de; Fernandes, P. D. Application techniques and concentrations of ascorbic acid to reduce saline stress in passion fruit. Plants, v.13, e2718, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13192718

» https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13192718 - Chapman, H. D.; Pratt, P. F. Methods of analysis for soils, plants and waters. Soil Science, v.93, p.68, 1962.

-

Dawood, M. F. A.; Zaid, A.; Latef, A. A. H. A. Salicylic acid spraying-induced resilience strategies against the damaging impacts of drought and/or salinity stress in two varieties of Vicia faba L. seedlings. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, v.41, p.1919-1942, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-021-10381-8

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-021-10381-8 -

Dias, M. dos S.; Reis, L. S.; Santos, R. H. S. dos.; Silva, F. de. A.; Santos J. P. de. O.; Paes, R. de A. Substratos e níveis de condutividade elétrica da água de irrigação no cultivo do rabanete. Revista em Agronegócio e Meio Ambiente, v.15, p.87-97, 2022. https://doi.org/10.17765/2176-9168.2022v15n1e9174

» https://doi.org/10.17765/2176-9168.2022v15n1e9174 -

DuBois, M.; Gilles, K. A.; Hamilton, J. K.; Rebers, P. T.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Analytical Chemistry, v.28, p.350-356, 1956. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac60111a017

» https://doi.org/10.1021/ac60111a017 -

Ehtaiwesh, A. F. The effect of salinity on nutrient availability and uptake in crop plants. Scientific Journal of Applied Sciences of Sabratha University, v.9, p.55-73, 2022. https://doi.org/10.47891/sabujas.v0i0.55-73

» https://doi.org/10.47891/sabujas.v0i0.55-73 -

El-Beltagi, H. S.; Ahmad, I.; Basit, A.; Shehata, W. F.; Hassan, U.; Shah, S. T.; Haleema, B.; Jalal, A.; Amin, R.; Khalid, M. A.; Noor, F.; Mohamed, H. I. Ascorbic acid enhances growth and yield of sweet peppers (Capsicum annum) by mitigating salinity stress. Gesunde Pflanzen, v.74, p.423-433, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10343-021-00619-6

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10343-021-00619-6 -

Elkelish, A.; Qari, S. H.; Mazrou, Y. M.; Abdelaal, K. A. A.; Hafez, Y. M.; Abu-Elsaoud, A. M.; Batiha, G.; El-Esawi, M.; El Nahhas, N. Exogenous ascorbic acid induced chilling tolerance in tomato plants through modulating metabolism, osmolytes, antioxidants, and transcriptional regulation of catalase and heat shock proteins. Plants, v.9, e431, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9040431

» https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9040431 -

Ferreira, D. F. Sisvar: a computer analysis system to fixed effects split plot type designs. Brazilian Journal of Biometrics, v.37, p.109-112, 2019. https://doi.org/10.28951/rbb.v37i4.450

» https://doi.org/10.28951/rbb.v37i4.450 -

Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M. H. M. B.; Parvin, K.; Bhuiyan, T. F.; Anee, T. I.; Nahar K.; Hossen, M. S.; Zulfiqar, F.; Alam, M. M.; Fujita, M. Regulation of ROS metabolism in plants under environmental stress: A review of recent experimental evidence. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, v.21, e8695, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21228695

» https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21228695 -

Hassan, A.; Fasiha, A. S.; Hamzah, S. M.; Yasmin, H.; Imran, M.; Riaz, M.; Ali, Q.; Ahmad Joyia, F.; Mobeen; Ahmed, S.; Ali, S.; Abdullah, A. A.; Nasser, A. M. Foliar application of ascorbic acid enhances salinity stress tolerance in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) through modulation of morpho-physio-biochemical attributes, ions uptake, osmo-protectants and stress response genes expression. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, v.28, p.4276-4290, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.03.045

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.03.045 -

Henschel, J. M.; Soares, V. de S.; Figueiredo, M. C.; Santos, S. K. dos; Dias, T. J.; Batista, D. S. Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) growth and gas exchange responses to exogenous ascorbic acid and irrigation levels. Vegetos, v.36, p.566-574, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42535-022-00422-2

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s42535-022-00422-2 -

Hernández-Herrera, R. M.; Sánchez-Hernández, C. V.; Palmeros-Suárez, P. A.; Ocampo-Alvarez, H.; Santacruz-Ruvalcaba, F.; Meza-Canales, I. D.; Becerril-Espinosa, A. Seaweed Extract Improves Growth and Productivity of Tomato Plants under Salinity Stress. Agronomy. v.12, e2495. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12102495

» https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12102495 -

Irigoyen, J. J.; Einerich, D. W.; Sánchez-Díaz, M. Water stress induced changes in concentrations of proline and total soluble sugars in nodulated alfalfa (Medicago sativa) plants. Physiologia Plantarum, v.84, p.55-60, 1992. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.1992.tb08764.x

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.1992.tb08764.x -

Kumari, S.; Chhillar, H.; Chopra, P.; Khanna, R. R.; Khan, M. I. R. Potassium: A track to develop salinity tolerant plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, v.167, p.1011-1023, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.09.031

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.09.031 -

Liang, W.; MA, X.; Wan, P.; Liu, L. Plant salt-tolerance mechanism: A review. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, v.495, p.286-291, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.11.043

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.11.043 -

Lutts, S.; Kinet, J. M.; Bouharmont, J. NaCl-induced senescence in leaves of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars differing in salinity resistance. Annals of Botany, v.78, p.389-398, 1996. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1996.0134

» https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1996.0134 -

Miller, G. L. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Analytical Chemistry , v. 31, p. 426-428, 1959. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac60147a030

» https://doi.org/10.1021/ac60147a030 -

Mishra, S.; Sharma, A.; Srivastava, A. K. Ascorbic acid: A metabolite switch for designing stress-smart crops. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, v.44, p.1350-1366, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/07388551.2023.2286428

» https://doi.org/10.1080/07388551.2023.2286428 -

Perveen, S.; Hussain, S. A. Methionine-induced changes in growth, glycinebetaine, ascorbic acid, total soluble proteins and anthocyanin contents of two Zea mays L. varieties under salt stress. JAPS: Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences, v.31, p.131-142, 2021. https://doi.org/10.36899/japs.2021.1.0201

» https://doi.org/10.36899/japs.2021.1.0201 -

Putti, F. F.; Cremasco, C. P.; Silva, J. F.; Gabriel Filho, L. R. Fuzzy modeling of salinity effects on radish yield under reuse water irrigation. Engenharia Agrícola, v.42, e215144, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4430-Eng.Agric.v42n1e215144/2022

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4430-Eng.Agric.v42n1e215144/2022 -

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2023. Available on: < Available on: https://www.rproject.org/ >. Accessed on: Nov. 2024.

» https://www.rproject.org/ -

Ribeiro, J. E. S.; Silva, A. G. C.; Coêlho, E. S.; Oliveira, P. H. A.; Silva, E. F. S.; Oliveira, A. K. S.; Santos, G. L.; Lima, J. V. L.; Silva, T. I.; Silveira, L. M.; Barros Júnior, A. P. Melatonin mitigates salt stress effects on the growth and production aspects of radish. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, v.48, e279006, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v28n4e279006

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v28n4e279006 -

Shabala, S.; Munns, R. Salinity stress: physiological constraints and adaptive mechanisms. In: Shabala, S. Plant stress physiology. Wallingford UK: Cabi, 2017. Cap.2, p.24-63. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781780647296.0024

» https://doi.org/10.1079/9781780647296.0024 -

Shafiq, F.; Iqbal, M.; Ashraf, M. A.; Ali, M. Foliar applied fullerol differentially improves salt tolerance in wheat through ion compartmentalization, osmotic adjustments and regulation of enzymatic antioxidants. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants, v.26, p.475-487, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-020-00761-x

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-020-00761-x -

Singh, P.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, J.; Saini, S.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, S.; Sinhmar, Y.; Kumar, D.; Sharma, A. Silicon supplementation alleviates the salinity stress in wheat plants by enhancing the plant water status, photosynthetic pigments, proline content and antioxidant enzyme activities. Plants, v.11, e2525, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11192525

» https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11192525 -

Wang, Y. H.; Zhang, G.; Chen, Y.; Gao, J.; Sun, Y. R.; Sun, M. F.; Chen, J. P. Exogenous application of gibberellic acid and ascorbic acid improved tolerance of okra seedlings to NaCl stress. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum, v.41, e93, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-019-2869-y

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-019-2869-y

Financing statement

Data availability

There are no supplementary sources.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

25 Aug 2025 -

Date of issue

Dec 2025

History

-

Received

31 Dec 2024 -

Accepted

12 May 2025 -

Published

07 July 2025

Ascorbic acid as a mitigator of salt stress effects on radish

Ascorbic acid as a mitigator of salt stress effects on radish

Means followed by same letters do not differ statistically by the Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The standard error was calculated based on the four replicates

Means followed by same letters do not differ statistically by the Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The standard error was calculated based on the four replicates

Means followed by same letters do not differ statistically by the Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The standard error was calculated based on the four replicates

Means followed by same letters do not differ statistically by the Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The standard error was calculated based on the four replicates

Means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ statistically for salt stress and means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ statistically for ascorbic acid concentrations by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05) in cases of significant interaction. In case of significance for the single factor, means followed by the same letters do not differ statistically by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The standard error was calculated based on the four replicates.

Means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ statistically for salt stress and means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ statistically for ascorbic acid concentrations by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05) in cases of significant interaction. In case of significance for the single factor, means followed by the same letters do not differ statistically by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The standard error was calculated based on the four replicates.

Means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ statistically for saline stress and means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ statistically for ascorbic acid concentrations by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05) in cases of significant interaction. In case of significance for the single factor, means followed by the same letters do not differ statistically by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The standard error was calculated based on the four replicates

Means followed by the same uppercase letters do not differ statistically for saline stress and means followed by the same lowercase letters do not differ statistically for ascorbic acid concentrations by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05) in cases of significant interaction. In case of significance for the single factor, means followed by the same letters do not differ statistically by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The standard error was calculated based on the four replicates

Means followed by same letters do not differ statistically by the Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The standard error was calculated based on the four replicates

Means followed by same letters do not differ statistically by the Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The standard error was calculated based on the four replicates

Means followed by same letters do not differ statistically by the Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The standard error was calculated based on the four replicates

Means followed by same letters do not differ statistically by the Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). The standard error was calculated based on the four replicates