ABSTRACT

Aluminum (Al) has long been regarded as toxic to plants, but recent research suggests it may also play a beneficial role in plant nutrition. Yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) is known for naturally thriving in acidic and Al-rich soils. The objective of the present study was to evaluate the effect of supplying Al, with or without the addition of controlled-release mineral fertilization, on the growth of yerba mate seedlings obtained from seeds. The mineral fertilization of the substrate enhanced the growth, biomass production, and quality of the produced yerba mate seedlings. Al supply did not exhibit beneficial effects on the development of seed-propagated yerba mate seedlings, except for root fresh volume, which showed a positive response to moderate Al doses. The yerba mate seedlings had a high tolerance to the presence of Al in the substrate, withstanding monthly applications of up to 1,000 mg Al3+ per dm-3 of substrate without displaying toxicity symptoms. Nevertheless, higher Al doses caused severe toxicity in yerba mate seedlings, which was visibly manifested by the development of short, thick, and dark-colored roots. In the shoot of the seedlings, Al toxicity symptoms generally occurred indirectly, as evidenced by reduced growth and a decrease in dry matter production. However, in the most affected plants, dark spots were observed on the shoot, starting at the tips of the younger leaves and progressing across the entire leaf, ultimately causing leaf abscission and, subsequently, plant death.

Key words:

acidic soil; beneficial element; toxic element; toxicity; plant nutrition

HIGHLIGHTS:

Yerba mate is the most widely cultivated non-timber forest species in Paraná state, Brazil.

Fertilization improved growth and quality of yerba mate seedlings.

Yerba mate seedlings showed tolerance to aluminum but developed toxicity at high doses.

RESUMO

O alumínio (Al) sempre foi tido como um elemento tóxico para as plantas. Por outro lado, pesquisadores da área de nutrição de plantas têm recentemente sugerido em considerar o Al como um elemento benéfico para as plantas. A erva-mate (Ilex paraguariensis) é conhecida por naturalmente se desenvolver bem em solos ácidos e ricos em Al. Objetivou-se avaliar o efeito do fornecimento de Al, associado ou não com a fertilização mineral de liberação controlada, sobre o desenvolvimento de mudas de erva-mate de procedência seminal. A adubação mineral do substrato aumentou fortemente o crescimento, a produção de biomassa e a qualidade das mudas de erva-mate produzidas. O fornecimento de Al não apresentou efeito benéfico sobre o crescimento das mudas de erva-mate, com exceção da variável volume fresco de raízes, que apresentou incremento em resposta a doses moderadas de Al. As mudas de erva-mate apresentaram alta tolerância à presença de Al no substrato, suportando aplicações mensais de até 1000 mg dm-3 de Al3+ sem resultar em sintomas de toxidez. Porém, dosagens de Al mais elevadas causaram severa toxidez para as mudas, tornando visualmente as raízes curtas, grossas e de coloração escura. Na parte aérea das mudas, os sintomas de toxidez de Al ocorreram, em geral, de forma indireta, verificado pelo menor crescimento e diminuição da produção de matéria seca. Porém, para as plantas mais afetadas pela toxidez de Al, observou-se manchas escuras na parte aérea, que se iniciaram nas pontas das folhas mais jovens, progredindo para todo o limbo foliar, resultando em abscisão e posteriormente levando a planta à morte.

Palavras-chave:

solo ácido; elemento benéfico; elemento tóxico; toxidez; nutrição de plantas

Introduction

Yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis A. St. Hil., Aquifoliaceae) is a tree species native to South America, found in regions encompassing Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay. In Southern Brazil, it plays an important socioeconomic and environmental role. Yerba mate primarily produces beverages, such as the traditional ‘chimarrão’, ‘tereré’, and mate tea. However, its use extends beyond beverages, as it serves as a raw material for various industrial products, including food preservatives, colorants, pharmaceuticals, and hygiene products (Penteado & Goulart, 2019; Girardi et al., 2024).

One of the most critical stages in yerba mate cultivation is seedling production. Therefore, proper management of mineral nutrition in forest nurseries is essential for rooting and the appropriate development of plants, aiming to produce high-quality yerba mate seedlings with an optimal cost-benefit ratio (Muchau Junior et al., 2024; Pinto et al., 2024).

Fertilization recommended for seedling production varies depending on the substrate used and is divided into three phases: nursery, growth, and hardening. The main fertilizers recommended for seedling nutrition during these phases are soluble industrialized mineral sources, predominantly urea (45% N), single superphosphate (±18% P2O5), potassium chloride (60% K2O), and FTE-BR-10 or FTE-BR-12 (as a source of micronutrients). However, controlled-release fertilizers, a recent technology promising to increase fertilization efficiency in nurseries, have recently been introduced. These fertilizers gradually solubilize in the substrate, releasing nutrients according to the plant‘s requirements, thereby reducing nutrient losses due to leaching. Furthermore, these fertilizers are applied to the substrate only once, when seedlings are transplanted into tubes or plastic bags, reducing the labor required for fertilizer application at different growth stages (Wendling & Santin, 2015; Menegatti et al., 2017).

Aluminum (Al) is the most abundant metal in the Earth‘s crust and exists in various forms in the soil (Echart & Cavalli-Molina, 2001). The cationic form of Al (Al3+) in the soil directly affects the availability of other soil nutrients for plant root absorption, influencing fertilization efficiency. Aluminum is a toxic element for most cultivated plant species, and its presence in concentrations above 1 mg dm-3 can negatively affect plant growth (Wendling & Santin, 2015; Korzune et al., 2021; Rahman & Upadhyaya, 2021).

However, other studies in plant nutrition have suggested that Al, in small concentrations in plant tissue, may offer growth benefits, with proposals to classify Al among the group of beneficial elements for plant species, along with elements such as silicon (Si), selenium (Se), cobalt (Co), vanadium (V), and sodium (Na) (Ghanati et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2020; Yamashita et al., 2020; Souza et al., 2023; Ofoe et al., 2023). However, more research is still needed to make such a general statement.

Yerba mate is known to grow and thrive in the acidic soils of Southern Brazil, which naturally contain high concentrations of Al3+ (Motta et al., 2020). The literature mentions that providing moderate doses of Al can stimulate the rooting of cuttings and initial growth in the clonal production of yerba mate seedlings (Benedetti et al., 2017; Ricardi et al., 2020).

As a result, it is widely believed among producers and technicians in the yerba mate sector that Al enhances the growth and development of the seedlings. However, even in clonal seedling production, very few studies have specifically examined the effects of Al on yerba mate growth and development, highlighting the need for more research to draw broader conclusions. Furthermore, in the case of seedlings derived from seeds, there is currently no scientific evidence on the effects of Al supplementation in the substrate for producing yerba mate seedlings propagated from seeds. It is believed that 90 to 95% of the yerba mate seedlings produced today come from seeds. Lastly, no studies have explored the feasibility of Al supplementation in field-level yerba mate plantations (post-seedling production phase).

This research aimed to evaluate the effect of supplying Al, with or without the addition of controlled-release mineral fertilization, on the development of seed-grown yerba mate seedlings.

Material and Methods

The experiment on yerba mate seedling production was conducted under nursery conditions at São Rafael Farm, located at the geographical coordinates 25° 29‘ 04“ S, 50° 17‘ 53.61“ W, with an altitude of 892 m, in the district of Vieiras, municipality of Palmeira, state of Paraná, Southern Brazil (Figure 1).

Georeferenced image of the experiment location, municipality of Palmeira, Paraná State, Brazil

According to the Köppen-Geiger climate classification (Köppen & Geiger, 1936), the climate in Palmeira is classified as Cfb, characterized by a humid environment with well-distributed precipitation throughout the year. The annual average rainfall ranges from 1,400 to 1,600 mm, with average temperatures between 17 and 18 °C. The region experiences well-defined seasons, with frost occurrences in winter, where the minimum temperature can reach -1.9 °C, and in the summer, temperatures can rise to a maximum of 28 °C. The region also receives an annual average of 2,000 hours of sunshine, according to the Climatic Atlas of the State of Paraná (Nitsche, 2019).

Yerba mate seeds were obtained by selecting 20 native mother trees from the region, on the farm within a forest fragment covering an area of approximately two hectares containing more than 50 seed-producing yerba mate trees. The mother trees are estimated to be over 100 years old, with trunks reaching up to 70 cm in diameter and heights up to 15 m. Seed collection from the forest fragment took place between January and April, using plastic nets placed under the canopy projection of the mother trees to collect mature fruits that naturally fell.

After harvesting the fruits from the mother trees and processing them, a sieve was used to remove impurities, followed by maceration using a steel mesh sieve to remove the pulp. The seeds were then washed under running water. The seeds were stratified in sand for 120 days to break dormancy. Subsequently, they were sown in beds containing a mixture of soil and coconut fiber, with periodic irrigation to maintain adequate moisture in the substrate, for an average period of 30 days until germination began. The need for irrigation was assessed daily based on the visual appearance of the substrate, ensuring it remained consistently moist but not saturated (Penteado Junior & Goulart, 2019).

For the installation of the experiment, newly germinated seedlings were selected based on uniformity in shoot height (average of 3.07 cm), collar diameter (average of 0.75 mm), and vigor. The seedlings were then transplanted into 110 cm3 plastic tubes filled with a commercial substrate (Carolina Soil®; pH 5.0, electrical conductivity 0.4 mS cm-1, maximum moisture content 60%, dry density 130 kg m-3), composed of peat, vermiculite, lime, and roasted rice husks. After transplanting, the yerba mate seedlings were cultivated in a nursery under 50% shade using shading screens and with irrigation applied as needed.

The experimental design was a randomized complete block design with four replications, arranged in a 2 × 7 factorial scheme, consisting of two fertilization treatments (with and without mineral fertilizer application to the substrate) and seven Al doses applied monthly to the substrate, namely 0 (no Al), 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 2500, and 3000 mg dm-3 (mg Al3+ per dm-3 of substrate), totaling 14 treatments. Therefore, the design comprised 56 experimental units (14 treatments × 4 experimental blocks), each unit containing four plants. Thus, each treatment consisted of 16 plants (4 blocks × 4 plants per experimental unit), totaling 224 yerba mate plants (14 treatments × 16 plants per treatment).

Mineral fertilization was applied to the substrate in the tubes in a single application during seedling transplanting by adding 3,000 mg per plant (amount of product per tube) of Basacote® Plus 9M fertilizer, which is a controlled-release, granular multi-nutrient fertilizer (16% N, 8% P2O5, 12% K2O, 1.2% Mg, 5% S, 0.02% B, 0.05% Cu, 0.4% Fe, 0.06% Mn, 0.015% Mo, and 0.02% Zn). Thus, by applying 3 g per plant (or 3,000 mg per plant) of the mineral fertilizer, the following nutrient amounts were provided: N = 480 mg per plant; P2O5 = 240 mg per plant; K2O = 360 mg per plant; Mg = 36 mg per plant; S = 150 mg per plant; B = 0.6 mg per plant; Cu = 1.5 mg per plant; Fe = 12 mg per plant; Mn = 1.8 mg per plant; Mo = 0.45 mg per plant; Zn = 0.6 mg per plant. Notably, the fertilizer used is a controlled-release type, not immediately soluble, with granules that dissolve gradually after being applied to the substrate, slowly supplying nutrients as the seedlings develop.

For each Al dose treatment (except the zero dose that received no Al), a solution was prepared using analytical-grade aluminum sulfate [Al2(SO4)3.(14-18)H2O]. The Al3+ solutions were prepared using reverse osmosis purified water (OS10LX model, Gehaka®).

The Al3+ solution was applied to the substrate at 30-day intervals. Over the experimental period, four applications of the Al3+ solution were made at 0, 30, 60, and 90 days after transplanting (DAT) the seedlings into the tubes. Day zero represents the start of the experimental period, that is, the day the yerba mate seedlings were transplanted into the tubes. The Al solutions were consistently applied in the morning.

Thus, considering the seven Al doses described in the experimental design [250, 500, 1000, 2000, 2500, and 3000 mg dm-3 (mg Al3+ per dm-3 of substrate)], and the volume of the substrate-filled tube (110 cm3), the amount of Al provided at each application was equivalent to 0, 27.5, 55, 110, 220, 275, and 330 mg per plant, respectively. After four applications (at 0, 30, 60, and 90 DAT), the total amount of Al supplied at each dose was 0, 110, 220, 440, 880, 1,100, and 1,320 mg per plant, respectively.

Four growth evaluations were conducted, consisting of plant height measured with a graduated ruler and collar diameter measured with a digital caliper. The evaluations were performed monthly, i.e., at 30, 60, 90, and 120 DAT.

At 120 DAT, after the final growth evaluation, the plants were harvested, and the substrate was removed from the roots using running water and a sieve to avoid root loss. Subsequently, the root fresh volume (RFV) was determined using a graduated cylinder and distilled water, following the method of Martins et al. (2011).

After drying the roots with paper towels and air, the seedlings were separated into shoots and roots using pruning shears and packed in labeled Kraft paper bags. The shoot and root fresh matter were determined using a digital analytical balance. Subsequently, the plant material was dried in a forced-air circulation oven at 58-60 °C until constant weight was reached (4 days). Afterward, shoot dry matter (SDM) and root dry matter (RDM) were determined using a digital balance.

Based on the growth and dry biomass production data obtained at 120 DAT, the Dickson quality index (DQI) for the seedlings was calculated (Dickson et al., 1960) according to the expression:

where:

DQI - Dickson quality index;

TDM - total dry matter of the seedling (SDM + RDM) (g);

SH - shoot height (cm);

CD - collar diameter (mm);

SDM - shoot dry matter (g); and,

RDM - root dry matter (g).

The data obtained were first subjected to normality and variance homogeneity tests using the Shapiro-Wilk and Bartlett tests, respectively, with the R statistical software (R Development Core Team, 2016). Subsequently, the data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA, p-value ≤ 0.05) with the SISVAR statistical software (Ferreira, 2011). Each experimental unit consisted of four plants, with four replications (experimental blocks), totaling 16 plants per treatment. The mean value of the four plants in the experimental unit was considered for each analyzed variable.

When a significant effect of fertilization treatments was detected, means were compared using Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). When a significant effect of Al doses was detected, regression models were fitted to describe the behavior of each response variable as a function of Al dose. Various models - linear, polynomial, transformed linear, and nonlinear - were tested depending on the nature of the response variable. Model selection was based on the significance of the regression coefficients (p ≤ 0.05), the coefficient of determination (R2), and the biological plausibility of the fitted curve (Motulsky & Christopoulos, 2004; Puiatti et al., 2013; Archontoulis & Miguez, 2017; Raudonius, 2017). Without a significant interaction between Al doses and fertilization but with a significant main effect of Al doses, a single regression curve was fitted based on the mean values across fertilization treatments. For variables that showed a significant interaction between factors (Al doses × fertilization), separate regression curves were fitted for each fertilization condition: the curve for unfertilized plants was plotted in blue, and that for fertilized plants in red. When ANOVA did not show a significant effect of Al doses (p > 0.05), the data were presented as horizontal lines across Al levels, representing the overall mean.

Results and Discussion

Table 1 summarizes the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for all variables evaluated in the experiment.

Summary of analysis of variance for shoot height and collar diameter at 30, 60, 90, and 120 days after transplanting (DAT), and shoot dry matter (SDM), root dry matter (RDM), root fresh volume (RFV), and Dickson quality index (DQI) at 120 DAT, as a function of fertilization treatments and aluminum (Al) doses applied monthly to the substrate

It is important to highlight that, in treatments with high Al doses, some plants died. In such cases, for experimental units with dead plants, the mean value was calculated based on all four plants in the unit, assigning a value of zero for dead plants. In the treatment with the highest Al dose (3,000 mg dm-3), where some experimental units exhibited total plant loss (death of all four plants in the unit), a value of zero was assigned to that replicate rather than treating it as missing data in the statistical analysis. This approach ensured that the toxic effect of Al was incorporated into the results, including plant mortality, even though this increased the coefficient of variation (CV%) in the analysis of variance (ANOVA).

If dead plants had been excluded from the statistical analysis and only the mean of the surviving plants in the experimental unit had been considered, the CV% in the ANOVA would have been reduced. However, the toxic effect of Al on the studied variables would have been underestimated. Additionally, the high CV% can also be attributed to genetic heterogeneity in Al tolerance among individuals within the same treatment, as the seedlings were seed-derived.

Nevertheless, despite the experimental variability observed in some variables, the effects of fertilization and Al doses were statistically highly significant, demonstrating that the treatments had consistent effects. Thus, the results accurately reflect the impact of Al doses on the development of seed-propagated yerba mate seedlings.

Plant shoot height was affected by the fertilization factor at 30 DAT and by the main effects (without interaction) of fertilization and Al dose factors at 60 and 90 DAT (Figure 2).

Plant height of yerba mate seedlings evaluated at 30 (A and B), 60 (C and D), and 90 (E and F) days after transplanting (DAT), in response to fertilization and monthly Al doses applied to the substrate

At 30 DAT, plant height was significantly affected by fertilization, but not by Al doses (Figures 2A and B). At this stage, seedlings grown in fertilized substrate reached heights approximately 12% greater than those grown in non-fertilized substrate.

At 60 DAT, fertilization increased plant height by approximately 36% (Figure 2C). In contrast, Al doses above 2,000 mg dm-3 caused a marked reduction in height, with the two highest doses (2,500 and 3,000 mg dm-3) reducing plant height by an average of 33%. At lower Al concentrations (250, 500, 1,000, and 2,000 mg dm-3), plant height remained similar to that observed in the control without Al (Figure 2D).

At 90 DAT, the effect of fertilization remained significant, with a 34% increase in plant height observed in fertilized seedlings compared to unfertilized ones (Figure 2E). The toxic effect of Al became more pronounced at this stage, with reductions in plant height beginning at 1,000 mg dm-3. The two highest Al doses led to average reductions of 37%, while 2,000 mg dm-3 caused a 20% decrease in plant height (Figure 2F).

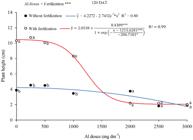

At 120 DAT, the effect of Al dose on plant height varied according to the substrate fertilization treatments, indicating a significant interaction between the factors (Figure 3).

Plant height of yerba mate seedlings evaluated at 120 days after transplanting (DAT) in response to monthly Al doses applied to the substrate and fertilization treatments

In the absence of fertilization, Al doses caused little change in plant height at 120 DAT, with a marked reduction only at the two highest doses. In contrast, under fertilized conditions, the three highest Al doses strongly reduced plant height at 120 DAT, with an average decrease of 33%, whereas the three lowest doses had virtually no effect. For comparison, at Al doses ranging from 0 to 1,000 mg dm-3, the average plant height was 2.4 times greater with fertilization. However, starting at the 2,000 mg dm-3 dose, mean height values did not differ between fertilized and non-fertilized treatments due to the pronounced toxic effect of Al on seedlings receiving mineral fertilization.

In addition to shoot height, collar diameter is another important variable for analyzing the seedling growth of forest species under nursery conditions. The effects of treatments on collar diameter were similar to those observed for plant height (Figure 4).

Collar diameter of yerba mate seedlings evaluated at 30 (A and B), 60 (C and D), and 90 (E and F) days after transplanting (DAT), in response to fertilization and monthly Al doses applied to the substrate

At 30 DAT, collar diameter was not significantly affected by fertilization (Figure 4A) or by Al doses (Figure 4B). At this stage, the values were consistent across all treatments, averaging approximately 1.16 mm.

At 60 DAT, a significant effect of fertilization was observed, with seedlings in fertilized substrate exhibiting a 16% greater collar diameter than unfertilized plants (Figure 4C). Al doses also had a significant effect, with the two highest doses (2,500 and 3,000 mg dm-3) reducing collar diameter by an average of 26% compared to the control (Figure 4D).

At 90 DAT, fertilization continued to promote seedling growth, resulting in a 23% increase in collar diameter compared to non-fertilized plants (Figure 4E). The adverse effect of Al became more evident starting at the 2,000 mg dm-3 dose. On average, the three highest Al doses (2,000, 2,500, and 3,000 mg dm-3) led to a 28% reduction in collar diameter compared to the lower doses (Figure 4F).

At 120 DAT, a significant interaction between Al doses and substrate fertilization was observed for collar diameter (Figure 5).

Collar diameter of yerba mate seedlings evaluated at 120 days after transplanting (DAT) in response to monthly Al doses applied to the substrate and fertilization treatments

Without substrate fertilization, collar diameter at 120 DAT showed slight variation at the lower Al doses, with more pronounced reductions observed at the three highest doses. In contrast, with substrate fertilization, collar diameter decreased by an average of 64% at the three highest Al doses (2,000, 2,500, and 3,000 mg dm-3), while no significant changes were observed among the lower doses. Thus, although fertilization increased collar diameter by 80% in the absence of Al, this positive effect was no longer evident under Al toxicity, which became pronounced at doses greater than 1000 mg dm-3.

Regarding the biomass production of yerba mate seedlings evaluated at 120 DAT, shoot (SDM) and root (RDM) dry matter were influenced by the interaction between factors (fertilization × Al doses) (Figure 6).

Shoot (A) and root (B) dry matter production of yerba mate seedlings evaluated at 120 days after transplanting (DAT) in response to monthly Al doses applied to the substrate and fertilization treatments

The shoot height and collar diameter results were reflected in shoot biomass production. Only minor variations in SDM were observed across Al doses ranging from 0 to 1,000 mg dm-3, regardless of whether the seedlings received substrate fertilization. However, from 2,000 mg dm-3 onward, Al toxicity led to a sharp reduction in SDM, with an average decrease of 75%. Substrate fertilization increased SDM by approximately 2.7-fold at the four lowest Al doses compared to unfertilized treatments. Nevertheless, this positive effect was no longer evident at Al doses greater than 1,000 mg dm-3, likely due to the toxic effects of excess Al, which minimized the differences between fertilized and non-fertilized seedlings (Figure 6A). The average shoot moisture content (stems + leaves) was 72%, based on fresh and oven-dried weights.

The fertilization status of the substrate influenced the effect of Al on root biomass. In the absence of fertilization, RDM production was low. It showed slight variation across Al doses, except at the two highest levels (2,500 and 3,000 mg dm-3), where the lowest RDM values were recorded. Under controlled-release fertilization, the four lowest Al doses (0, 250, 500, and 1,000 mg dm⁻³) promoted a 2.0-fold increase in RDM compared to non-fertilized seedlings, with slight variation among these doses. However, excess Al at the three highest Al doses (≥ 2,000 mg dm-3) resulted in a marked reduction in root biomass, representing a 69% decrease compared to the average of the four lowest doses. Under these conditions, no significant differences in RDM were observed between fertilized and non-fertilized treatments (Figure 6B).

Aluminum plays a dual role in plant development, acting as a toxic element for most species while benefiting certain plants adapted to acidic soils. Al toxicity primarily affects root systems by inhibiting cell division and impairing water and nutrient uptake, ultimately reducing shoot growth. However, some species exhibit a positive response to Al under acidic conditions. Research on tea plants has shown that Al is beneficial and essential for root growth and development. The absence of Al disrupts root meristem activity, halts root elongation, and induces DNA damage in meristematic cells. Furthermore, Al accumulation in tea plant shoots has been linked to enhanced photosynthesis and metabolic activity, indicating a broader physiological role in plant growth. These findings underscore the species-specific nature of Al responses and highlight the need for further research to better understand its effects on different plant species (Sun et al., 2020).

Ricardi et al. (2020) found that the application of 9,000 mg dm-3 of aluminum sulfate [Al2(SO4)3], corresponding to approximately 1,420 mg Al3+ dm-3, had a positive effect on increasing leaf area in clonal yerba mate seedlings. However, unlike the present study, the authors applied aluminum sulfate as a single dose directly to the rooting substrate of yerba mate cuttings, which measured 6 to 10 cm in length. These cuttings were obtained from three-year-old mother plants of the BRS BLD Aupaba cultivar, grown in a semi-hydroponic system within a clonal mini-garden. The cuttings were planted in 50 cm3 tubes containing substrate with specific Al³⁺ concentrations.

In a hydroponic cultivation system with approximately four-month-old clonal yerba mate seedlings obtained through mini-cuttings, Benedetti et al. (2017) observed an increase in root production following the application of Al3+ to the nutrient solution at concentrations close to 1300 µmol L-1 (equivalent to approximately 35.07 mg L-1 of Al3+). However, the optimal Al3+ dose varied depending on the clonal material used.

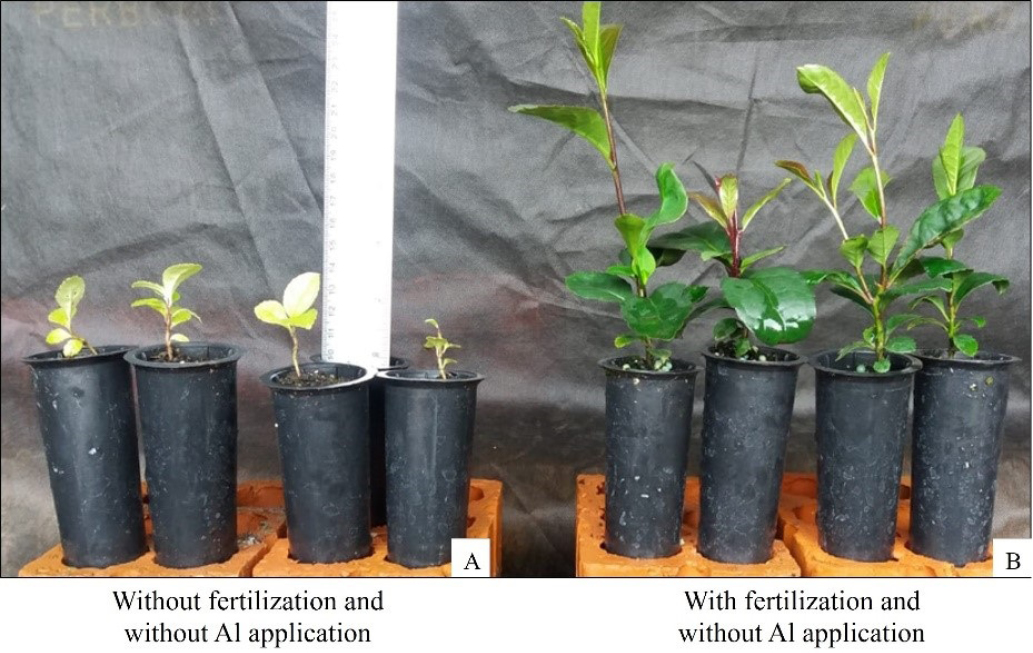

The absence of fertilization reduced shoot and root biomass production of yerba mate seedlings but did not affect the root system morphology (Figure 7). On the other hand, in addition to reducing shoot and root biomass production, Al toxicity caused morphological changes in the roots (Figure 8).

Visual aspect of the shoot of yerba mate seedlings in the plot without fertilization and without Al application (A) and plot with fertilization and without Al application (B) at 120 days after transplanting

Visual aspect of the root system of yerba mate seedlings at 120 days after transplanting, in the plot without fertilization and with 250 mg Al3+ per dm-3 of substrate (A), plot without fertilization and with 3,000 mg Al3+ dm-3 (B), plot with fertilization and with 250 mg Al3+ dm-3 (C), and plot with fertilization and with 3,000 mg Al3+ dm-3 (D). Figures A and C demonstrate the difference in root biomass production between treatments without and with fertilization, respectively. Figures B and D illustrate the modification of root system morphology due to the toxicity observed at higher Al doses, regardless of fertilization

For some plants, Al toxicity symptoms in the shoot were indirect, resulting in lesser growth and SDM production (Figure 9). However, the toxicity symptoms in the shoot were directly manifested in other plants negatively affected by Al. They initially appeared as dark spots at the tips of younger leaves, which later spread to the entire leaf blade, leading to the abscission of affected leaves and eventual plant death (Figure 10).

Visual aspect of yerba mate seedlings at 120 days after transplanting (A) Plants without Al3+ toxicity, demonstrating proper development of the shoot and root system, with roots displaying a light color; (B) Plants with Al3+ toxicity, illustrating the adverse effect on shoot development and, particularly, on root system morphology, with roots displaying a dark color

Plots at 90 days after transplanting that had a high mortality rate of yerba mate plants due to Al toxicity

According to Echart & Cavalli-Molina (2001), plant species vary in their ability to tolerate Al, and this variation extends to individuals within the same species, depending on the genotype. Supporting this assertion, Benedetti et al. (2017) found that different yerba mate clones responded differently to Al doses. Similarly, some plant species can accumulate high concentrations of Al3+ without displaying toxicity symptoms associated with this element. Examples include Melastoma malabathricum L. (melastoma), Fagopyrum esculentum Moench (buckwheat), and Camellia sinensis L. (tea plants). These species mitigate Al toxicity through ligands, such as organic acids, or by isolating Al in insensitive locations, such as vacuoles (Nagata et al., 1992; Watanabe & Osaki, 2002).

Root fresh volume (RFV) and the Dickson quality index (DQI) of yerba mate seedlings were influenced by the interaction between fertilization and Al doses (fertilization × Al doses) (Figure 11).

Root fresh volume (A) and Dickson quality index (B) of yerba mate seedlings evaluated at 120 days after transplanting in response to monthly Al doses applied to the substrate and fertilization treatments

In non-fertilized treatments, RFV showed a slight increase at the lower Al doses (250 and 500 mg dm-3), followed by a reduction from 1,000 mg dm-3 onward, with a more pronounced decline at the two highest Al levels. Similarly, in fertilized treatments, RFV was higher at 250 and 500 mg Al3+ dm-3 of substrate compared to the control (0 mg dm-3), a response well captured by the adjusted regression model. However, a marked reduction in RFV was observed at the three highest Al doses, likely due to Al toxicity, which negatively affected root system development. The role of substrate fertilization in promoting root growth is noteworthy, as in the absence of Al toxicity, fertilization increased RFV by an average of 3.9-fold compared to the corresponding non-fertilized treatment. Notably, RFV was the only variable in this study that exhibited a positive response to Al supplied at moderate doses (Figure 11A).

As a result of the growth and dry matter production data, yerba mate seedlings with the highest DQI values were obtained in the treatments that received mineral fertilizer and Al doses ranging from 0 to 1,000 mg dm-3 of soil, with DQI values ranging from 0.084 to 0.111. In treatments without mineral fertilizer and with Al doses ranging from 0 to 1,000 mg dm-3 of substrate, the DQI ranged from 0.035 to 0.049. At Al doses ranging from 2,000 to 3,000 mg dm-3 of substrate, the DQI ranged from 0.004 to 0.037, with or without mineral fertilizer. Thus, substrate fertilization and the absence of Al toxicity were essential for producing high-quality yerba mate seedlings (Figure 11B).

Supporting this research, Pimentel et al. (2017) found DQI values ranging from 0.07 to 0.12 in yerba mate seedlings produced by vegetative propagation and evaluated at 120 days of cultivation. Ricardi et al. (2020) found DQI values ranging from 0.17 to 0.42, depending on Al3+ doses in clonal yerba mate seedlings evaluated at 300 days of age. Thus, DQI values in yerba mate seedlings appear to increase as the seedling ages.

The Dickson Quality Index (DQI) is widely recognized as a robust measure for assessing the quality of forest seedlings. Developed by Dickson et al. (1960), the DQI integrates multiple morphological parameters, such as shoot height, collar diameter, and the dry mass of both the shoot and root system, providing a comprehensive evaluation of seedling robustness and biomass allocation balance.

The significance of the DQI lies in its ability to predict seedling performance after transplanting. Seedlings with high DQI values tend to exhibit greater vigor and higher survival rates in the field, as the index reflects a balanced growth between the shoot and root system. This balance is crucial for plants to withstand adverse conditions and establish themselves in the planting environment. Studies have demonstrated that the DQI is a reliable indicator of seedling quality, serving as a reference for selecting batches for reforestation and ecological restoration projects. By considering the DQI in the evaluation of forest seedlings, it is possible to ensure that only individuals with adequate growth potential and adaptability are used in planting projects, thereby increasing the efficiency and success of these initiatives (Gomes et al., 2002; Smiderle & Souza, 2016).

Except for RFV, no beneficial effects of Al were observed on the development of seed-origin yerba mate seedlings at any of the Al doses tested. These findings contrast with those previously reported for clonal yerba mate seedlings, in which positive effects of Al supply on rooting and overall seedling development were documented (Benedetti et al., 2017; Ricardi et al., 2020).

On the other hand, yerba mate seedlings demonstrated tolerance to Al³⁺ up to the dose of 1,000 mg dm-3. Considering that this Al dose was applied monthly to the substrate, four applications were made during the experimental period, totaling 4,000 mg dm-3 (four applications of 1,000 mg dm-3 each). In this case, seed-origin yerba mate seedlings exhibit high tolerance to high Al concentrations in the substrate compared to other cultivated plant species.

However, from the dose of 2,000 mg dm-3 of Al3+ (equivalent to 8,000 mg dm-3 after four applications), Al toxicity symptoms were observed in the yerba mate seedlings, which strongly manifested in the morphology of the root system, as presented in the results.

Thus, at the three highest Al doses (2,000, 2,500, and 3,000 mg dm-3 of substrate), it was evident that Al toxicity in yerba mate seedlings initially manifested strongly in the roots, altering root system morphology by making the roots short, thick, and dark. Consequently, over time, for some plants, the Al toxicity symptom manifested only indirectly in the shoot, resulting in reduced growth and biomass production. However, for some plants, Al toxicity symptoms in the shoot occurred directly, initially appearing visually at the tips of the youngest leaves as a dark spot, which later spread across the entire leaf blade, leading to leaf abscission and, ultimately, plant death.

According to Hartwig et al. (2007), Al in the soil inhibits root growth and development, altering water and nutrient absorption and reducing overall plant development. Al is not considered an essential element for plant species, but plants naturally contain Al in their tissues. Al is present in most acidic soils in Brazil and is naturally absorbed by plants through ion-transporting membrane proteins, allowing it to enter root cells. Al exerts toxic effects on roots by inhibiting cell division and elongation, negatively impacting the roots’ ability to absorb water and nutrients and altering biochemical signaling in physiological processes (Tatsch et al., 2010; Vicensi et al., 2020; Chauhan et al., 2021). Aluminum toxicity symptoms in plants include thickened roots with yellowish tips, twisted dark-colored secondary roots, and absence of root hairs (Rahman & Upadhyaya, 2021; Hajiboland et al., 2023; Ofoe et al., 2023).

In addition to changes in root system morphology and reduced shoot and root biomass production, plant death due to Al toxicity began at 60 DAT in unfertilized treatments and at 30 DAT in the fertilized treatments. Table 2 presents the number of dead plants resulting from toxicity in the three highest Al3+ doses.

Mortality of yerba mate plants at 30, 60, 90, and 120 DAT in response to fertilization and monthly application of seven Al³⁺ doses

It should be noted that in this experiment, each experimental unit consisted of four plants. Thus, in the experimental units that showed Al toxicity in the plants (three highest Al3+ doses), the death of two or three plants was observed. In contrast, the remaining plants (one or two plants) continued to develop until the end of the experiment, but with reduced growth and decreased shoot dry matter production. An exception occurred in the treatments that received the highest Al dose, where some experimental units recorded the death of all four plants of the experimental unit (Figure 10). This is likely related to genotype, as seeds came from 20 mother trees, making it evident that some individuals had a higher tolerance to Al toxicity due to genetic characteristics.

Yerba mate exhibits this adaptation, being a species that naturally grows well in the acidic, Al-saturated soils of Southern Brazil (Girardi et al., 2024). In this context, Benedetti et al. (2017) found that different yerba mate clones subjected to the exact Al3+ dosage presented variations in tolerance to the element. According to the author, yerba mate’s tolerance to Al may be related to phenolic compounds in the species’ tissues.

There are reports that low or moderate Al doses in the growing medium can benefit the development of clonal yerba mate seedlings, particularly for root elongation and volume (Benedetti et al., 2017). Additionally, in the production of yerba mate seedlings via vegetative propagation, the supply of 1,440 mg of Al dm-3 in the substrate enhanced seedling growth. However, the application of 2,880 mg dm-3 resulted in toxicity for clonal yerba mate seedlings (Ricardi et al., 2020). In a study on tea plants (Camellia sinensis L.), the authors found that Al can be considered a beneficial element, as it stimulates plant growth by increasing Al-induced antioxidant activity. This results in greater membrane integrity, lignification, and delayed plant aging (Ghanati et al., 2005).

Yamashita et al. (2020) conducted a study to evaluate the effects of pH and Al on tea plant growth and found that Al was beneficial for plant growth. The authors also observed that, in new roots, the levels of most cationic nutrients, such as Ca2+, Cu2+, Mg2+, Fe2+, K+, and Zn2+, were reduced by adding Al3+. However, the content of these elements was not affected in the leaves. These results suggest that Al inhibited the absorption of many cationic elements. However, in its beneficial role, Al may aid in efficiently translocating these elements from roots to shoots. Therefore, Al may complement the nutritional functions of these cationic elements and promote good growth in nutrient-poor environments, such as Brazil’s acidic soils.

The importance of mineral fertilization in the substrate to produce yerba mate seedlings was demonstrated. In this research, controlled-release fertilizer was used. These fertilizers are generally composed of granules containing plant nutrients. However, they are enclosed in a semipermeable membrane that contracts with temperature and gradually releases nutrients osmotically into the substrate. Thus, compared to conventional mineral fertilizers, the use of controlled-release fertilizers results in lower leaching losses and allows for nutrient supply to plants according to their needs, increasing fertilization efficiency and reducing toxicity risks (Rossa et al., 2011).

Moraes Neto et al. (2003) found that the application of controlled-release fertilizers to produce Guazuma ulmifolia (mutambo), Croton floribundus (capixingui), Peltophorum dubium (canafístula), Gallesia integrifolia (pau-d’alho), and Myroxylon peruiferum (cabreúva) seedlings resulted in greater development compared to seedlings that did not receive this type of fertilization. Duboc (2018) also used controlled-release fertilizer to produce Cedrela fissilis seedlings, achieving better seedling development.

According to Smiderle et al. (2020), applying controlled-release fertilizers to produce Agonandra brasiliensis seedlings stimulated height growth and collar diameter. Emer et al. (2020) found that applying doses of controlled-release fertilizer increased the growth of Campomanesia aurea seedlings.

In summary, the findings of this study indicate that the monthly supply of Al applied via nutrient solution (fertigation) to the substrate surface did not enhance the growth of seed-origin yerba mate seedlings at any tested dosage. However, the seedlings exhibited remarkable tolerance to the monthly application of Al doses up to 1,000 mg Al3+ per dm-3 of substrate, reinforcing the adaptability of yerba mate to acidic soils naturally rich in Al. From a physiological perspective, while Al is traditionally considered toxic to plants, some species exhibit varying degrees of tolerance and even potential benefits at low doses (Sun et al., 2020). However, in this study, toxicity symptoms became evident at higher monthly Al doses (≥ 2,000 mg dm-3), mainly affecting root morphology and, consequently, shoot development. The lack of beneficial responses to Al supplementation in seed-origin seedlings contrasts with previous findings on clonal propagation systems (Benedetti et al., 2017; Ricardi et al., 2020), emphasizing the need for species- and propagation-method-dependent research on aluminum’s role in plant development.

Beyond the experimental results, this research holds significant implications for the sustainable cultivation of yerba mate in Southern Brazil. The species plays a crucial role in agroforestry systems and small-scale agriculture, often cultivated in remnants of Mixed Ombrophilous Forests, as occurs in the state of Paraná. The ability of yerba mate to thrive in acidic, Al-rich soils without requiring chemical soil amendments highlights its ecological importance in biodiversity conservation and land-use sustainability. Additionally, optimizing fertilization strategies, as demonstrated in this study, can improve seedling quality, ensuring higher survival rates and better productivity under field conditions. This has direct socioeconomic benefits for small-scale farmers who depend on yerba mate as a source of income. Therefore, while the monthly application of Al via nutrient solution does not enhance seedling growth, ensuring adequate fertilization and nursery management practices is essential for maintaining the viability and sustainability of yerba mate cultivation in Brazil.

Conclusions

-

The fertilization of the substrate, using controlled-release fertilizer, increased shoot height, collar diameter, biomass production in both shoots and roots and the quality of the produced yerba mate seedlings.

-

The supply of aluminum (Al) did not exhibit beneficial effects on the development of seed-grown yerba mate seedlings, except for root fresh volume, which presented a positive response to moderate Al doses.

-

Yerba mate seedlings exhibited high tolerance to Al in the substrate, withstanding monthly applications of up to 1,000 mg Al3+ dm-3 without displaying toxicity symptoms.

-

Monthly applications of Al doses starting from 2,000 mg dm-3 resulted in severe toxic effects on the yerba mate seedlings.

Literature Cited

-

Archontoulis, S. V.; Miguez, F. E. Nonlinear regression models and applications in agricultural research. Agronomy Journal, v.107, p.786-798, 2015. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2012.0506

» https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2012.0506 -

Benedetti, E. L.; Santin, D.; Barros, N. F. De; Pereira, G. L.; Martinez, H. P.; Lima Neves, J. C. Alumínio estimula o crescimento radicular de erva-mate? Pesquisa Florestal Brasileira, v.37, p.139-147, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4336/2017.pfb.37.90.983

» https://doi.org/10.4336/2017.pfb.37.90.983 -

Chauhan, D. K.; Yadav, V.; Vaculík, M.; Gassmann, W.; Pike, S.; Arif, N.; Singh, V. P.; Deshmukhf, R.; Sahig, S.; Tripathi, D. K. Aluminum toxicity and aluminum stress-induced physiological tolerance responses in higher plants. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, v.41, p.715-730, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/07388551.2021.1874282

» https://doi.org/10.1080/07388551.2021.1874282 -

Dickson, A.; Leaf, A.; Hosner, J. F. Quality appraisal of white spruce and white pine seedling stock in nurseries. The Forest Chronicle, v.36, p.10-13, 1960. https://doi.org/10.5558/tfc36010-1

» https://doi.org/10.5558/tfc36010-1 -

Duboc, E.; De Sá Motta, I.; Santiago, E. F.; Meira, R.; Nascimento, A. M.; Martini, L. V. R. Substrato orgânico e adubação com fertilizante de liberação controlada na produção de mudas de cedro-rosa (Cedrela fissilis). Cadernos de Agroecologia, v.13, p.10-10, 2018. https://cadernos.aba-agroecologia.org.br/cadernos/article/view/2160/2104

» https://cadernos.aba-agroecologia.org.br/cadernos/article/view/2160/2104 -

Echart, C. L.; Cavalli-Molina, S. Fitotoxicidade do alumínio: efeitos, mecanismo de tolerância e seu controle genético. Ciência Rural, p.531-541, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0103-84782001000300030

» https://doi.org/10.1590/s0103-84782001000300030 -

Emer, A. A.; Winhelmann, M. C.; Tedesco, M.; Fior, C. S.; Schafer, G. Controlled release fertilizer used for the growth of Campomanesia aurea seedlings. Ornamental Horticulture, v.26, p.35-44, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1590/2447-536X.v26i1.2020

» https://doi.org/10.1590/2447-536X.v26i1.2020 -

Ferreira, D. F. Sisvar: a computer statistical analysis system. Ciência e Agrotecnologia, v.35, p.1039-1042, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-70542011000600001

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-70542011000600001 -

Ghanati, F.; Morita, A.; Yokota, H. Effects of aluminum on the growth of tea plant and activation of antioxidant system. Plant and Soil, v.276, p.133-141, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-005-3697-y

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-005-3697-y -

Girardi, E.; Zampier, I. F.; Petranski, P. H.; Lombardi, K. C.; De Ávila, F. W. Soil fertility and yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis A. St. Hil.) growth under sheep manure or mineral fertilization in monoculture or intercropped with Mimosa scabrella Benth. Agroforestry Systems, v.98, p.81-101, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-023-00892-6

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-023-00892-6 -

Gomes, J. M.; Couto, L.; Leite, H. G.; Xavier, A.; Garcia, S. L. R. Parâmetros morfológicos na avaliação da qualidade de mudas de Eucalyptus grandis Revista Árvore, v.26, p.655-664, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-67622002000600002

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-67622002000600002 -

Hajiboland, R.; Panda, C. K.; Lastochkina, O.; Gavassi, M. A.; Habermann, G.; Pereira, J. F. Aluminum toxicity in plants: Present and future. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, v.42, p.3967-3999, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-022-10866-0

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-022-10866-0 -

Hartwig, I. Mecanismos associados à tolerância ao alumínio em plantas. Semina: Ciências Agrárias, v.28, p.219-228, 2007. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4457/445744084008.pdf

» https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4457/445744084008.pdf -

Köppen, W.; Geiger, R. Das geographische system der klimate. In: Handbuch der klimatologie. Berlim: Gebrüder Borntraeger, 1936. v.1, p.1-44. https://koeppen-geiger.vu-wien.ac.at/pdf/Koppen_1936.pdf

» https://koeppen-geiger.vu-wien.ac.at/pdf/Koppen_1936.pdf -

Korzune, M.; Ávila, F. W.; Botelho, R. V.; Muller, M. M. L.; Petranski, P. H.; Pinto, E. L. C. T.; Aksenen, T.; Jadoski, S. O.; Rampim, R. Effects of gypsum on growth and nutrient status of forage grasses cultivated between the rows of organically grown Satsuma mandarin in an Oxisol from subtropical Brazil. Crop and Pasture Science, v.72, p.899-912, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1071/CP21316

» https://doi.org/10.1071/CP21316 -

Martins, L. D.; Rodrigues, W. N.; Tomaz, M. A.; De Souza, A. F.; De Jesus Jr., W. C. Função de crescimento vegetativo de mudas de cafeeiro conilon a níveis de ciproconazol+tiametoxam e nitrogênio. Revista de Ciências Agrárias, v.35, p.173-183, 2012. https://doi.org/10.19084/rca.16171

» https://doi.org/10.19084/rca.16171 -

Menegatti, R. D.; Navroski, M. C.; Guollo, K.; Fior, C. S.; Souza, A. G.; Possenti, J. C. Formação de mudas de guatambu em substrato com hidrogel e fertilizante de liberação controlada. Revista Espacios, v.38, p.35-47, 2017. https://www.revistaespacios.com/a17v38n22/a17v38n21p35.pdf

» https://www.revistaespacios.com/a17v38n22/a17v38n21p35.pdf -

Moraes Neto, S. P. D.; Gonçalves, J. L. D. M.; Arthur Junior, J. C.; Ducatti, F.; Aguirre Junior, J. H. Fertilização de mudas de espécies arbóreas nativas e exóticas. Revista Árvore , v.27, p.129-137, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-67622003000200002

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-67622003000200002 -

Motta, A. C. V.; Barbosa, J. Z.; Magri, E.; Pedreira, G. Q.; Santin, D.; Prior, S. A.; Consalter, R.; Young, S. D.; Broadley, M. R.; Benedetti, E. L. Elemental composition of yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis A.St.-Hil.) under low input systems of southern Brazil. Science of The Total Environment, v.736, e139637, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139637

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139637 - Motulsky, H.; Christopoulos, A. Fitting models to biological data using linear and nonlinear regression: a practical guide to curve fitting. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

-

Muchau Junior, A. C.; Lopes, A. L.; Vier, C. R.; Peres, F. S. B.; Lombardi, K. C.; De Ávila, F. W. Use of sewage sludge in the production of yerba mate seedlings. Caderno Pedagógico, v.21, e10799, 2024. https://doi.org/10.54033/cadpedv21n12-160

» https://doi.org/10.54033/cadpedv21n12-160 -

Nagata, T.; Hayatsu, M.; Kosuge, N. Identification of aluminium forms in tea leaves by 27Al NMR. Phytochemistry, v.31, p.1215-1218, 1992. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9422(92)80263-E

» https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9422(92)80263-E -

Nitsche, P. R.; Caramori, P. H.; Ricce, W. D. S.; Pinto, L. F. D. Atlas climático do estado do Paraná - Londrina (PR): Instituto Agronômico do Paraná, 210p. 2019. https://www.idrparana.pr.gov.br/Pagina/Atlas-Climatico

» https://www.idrparana.pr.gov.br/Pagina/Atlas-Climatico -

Ofoe, R.; Thomas, R. H.; Asiedu, S. K.; Wang-Pruski, G.; Fofana, B.; Abbey, L. Aluminum in plant: Benefits, toxicity and tolerance mechanisms. Frontiers in Plant Science, v.13, e1085998, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1085998

» https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1085998 -

Penteado Junior, J. F.; Goulart, I. C. G. dos R. Erva 20: Sistema de produção de erva-mate. Brasília: Embrapa, 2019. 152p. https://www.embrapa.br/busca-de-publicacoes/-/publicacao/1106677/erva-20-sistema-de-producao-para-erva-mate

» https://www.embrapa.br/busca-de-publicacoes/-/publicacao/1106677/erva-20-sistema-de-producao-para-erva-mate -

Pimentel, N.; Lencina, K. H.; Pedroso, M. F.; Somavilla, T. M.; Bisognin, D. A. Morphophysiological quality of yerba mate plantlets produced by mini-cuttings. Semina: Ciências Agrárias , v.38, p.3515-3528, 2017. https://doi.org/10.5433/1679-0359.2017v38n6p3515

» https://doi.org/10.5433/1679-0359.2017v38n6p3515 -

Pinto, E. L. C. T.; Muchau Junior, A. C.; Rocha, J.; dos Santos, P. R.; Girardi, E.; de Ávila, F. W. Desenvolvimento de mudas de erva-mate com o uso de regulador de crescimento vegetal. Caderno Pedagógico , v.21, e10445, 2024. https://doi.org/10.54033/cadpedv21n12-091

» https://doi.org/10.54033/cadpedv21n12-091 -

Puiatti, G. A.; Cecon, P. R.; Nascimento, M.; Puiatti, M.; Finger, F. L.; Silva, A. R. da; Nascimento, A. C. C. Análise de agrupamento em seleção de modelos de regressão não lineares para descrever o acúmulo de matéria seca em plantas de alho. Revista Brasileira de Biometria, v.31, p.337-351, 2013. https://biometria.ufla.br/antigos/fasciculos/v31/v31_n3/A2_Guilherme_PauloCecon.pdf

» https://biometria.ufla.br/antigos/fasciculos/v31/v31_n3/A2_Guilherme_PauloCecon.pdf - R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2016.

-

Rahman, R.; Upadhyaya, H. Aluminium toxicity and its tolerance in plant: A review. Journal of Plant Biology, v.64, p.101-121, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12374-020-09280-4

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s12374-020-09280-4 -

Raudonius, S. Application of statistics in plant and crop research: important issues. Zemdirbyste-Agriculture, v.104, p.377-382, 2017. https://doi.org/10.13080/z-a.2017.104.048

» https://doi.org/10.13080/z-a.2017.104.048 -

Ricardi, A. C.; Koszalka, V.; Lopes, C.; Watzlawick, L. F.; Ben, T. J.; Umburanas, R. C.; Muller, M. M. L. O alumínio melhora o crescimento e a qualidade de mudas clonais de erva-mate (Ilex paraguariensis, Aquifoliaceae). Research, Society and Development, v.9, e419108064, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v9i10.8064

» http://dx.doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v9i10.8064 -

Rossa, Ü. B.; Angelo, A. C.; Nogueira, A. C.; Reissmann, C. B.; Grossi, F.; Ramos, M. R. Fertilizante de liberação lenta no crescimento de mudas de Araucaria angustifolia e Ocotea odorifera Floresta, v.41, e13234, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/rf.v41i3.24040

» http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/rf.v41i3.24040 -

Smiderle, O. J.; Souza, A. G. das. Production and quality of Cinnamomum zeylanicum Blume seedlings cultivated in nutrient solution. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Agrárias, v.11, p.104-111, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.5039/agraria.v11i2a5364

» http://dx.doi.org/10.5039/agraria.v11i2a5364 -

Smiderle, O. J.; Montenegro, R. A.; Souza, A. D. G.; Chagas, E. A.; Dias, T. J. Container volume and controlled-release fertilizer influence the seedling quality of Agonandra brasiliensis Pesquisa Agropecuária Tropical, v.50, e62134, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-40632020v5062134

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-40632020v5062134 -

Souza, C. M. de; Almeida, V. G. S. de; Brito, G. S.; Jess Neto, A. T. de; Souza, G. S. de; Freire, E. M.; Dias, D. O. Doses de alumínio no crescimento inicial de plantas de aboboreira em cultivo semi-hidropônico: Aluminum doses in the initial growth of squash plants in semi-hydroponic cultivation. Brazilian Journal of Animal and Environmental Research, v.6, e1323234, 2023. https://doi.org/10.34188/bjaerv6n3-053

» https://doi.org/10.34188/bjaerv6n3-053 -

Sun, L.; Zhang, M.; Liu, X.; Mao, Q.; Shi, C.; Kochian, L. V.; Liao, H. Aluminium is essential for root growth and development of tea plants (Camellia sinensis). Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, v.62, p.984-997, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jipb.12942

» https://doi.org/10.1111/jipb.12942 -

Vicensi, M.; Lopes, C.; Koszalka, V.; Umburanas, R. C.; Vidigal, J. C. B.; de Ávila, F. W.; Müller, M. M. L. Soil fertility, root and aboveground growth of black oat under gypsum and urea rates in no till. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, v.20, p.1271-1286, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-020-00211-3

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-020-00211-3 -

Watanabe, T.; Osaki, M. Role of organic acids in aluminum accumulation and plant growth in Melastoma malabathricum Tree Physiology, v.22, p.785-792, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/22.11.785

» https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/22.11.785 -

Wendling, I.; Santin, D. Propagação e nutrição de erva-mate. Brasília: Embrapa , 2015. 195p. https://ainfo.cnptia.embrapa.br/digital/bitstream/doc/1013131/1/EmbrapaFlorestas-2015-PropagacaoNutricaoErvaMate.pdf

» https://ainfo.cnptia.embrapa.br/digital/bitstream/doc/1013131/1/EmbrapaFlorestas-2015-PropagacaoNutricaoErvaMate.pdf -

Yamashita, H.; Fukuda, Y.; Yonezawa, S.; Morita, A.; Ikka, T. Tissue ionome response to rhizosphere pH and aluminum in tea plants (Camellia sinensis L.), a species adapted to acidic soils. Plant-Environment Interactions, v.1, p.152-164, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/pei3.10028

» https://doi.org/10.1002/pei3.10028

Financing statement

-

The authors express their gratitude to São Rafael Farm, located in the district of Vieiras, municipality of Palmeira, Paraná State, Brazil, and to the Forest Soils Laboratory of UNICENTRO, in Irati, Paraná State, Brazil, for their support in conducting the experiments. The authors also acknowledge the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES; Finance Code 001), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Brazil), and the Araucaria Foundation (State of Paraná, Brazil) for providing research fellowships. Additionally, the authors thank the Graduate Program in Forest Sciences at UNICENTRO (PPGF/UNICENTRO) for the financial support provided for translation services.

Data availability

There is no additional research data.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

01 Sept 2025 -

Date of issue

Dec 2025

History

-

Received

25 Oct 2024 -

Accepted

04 July 2025 -

Published

16 July 2025

Impact of aluminum supply on the growth of seed-grown yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) seedlings

Impact of aluminum supply on the growth of seed-grown yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) seedlings

Source: Eduardo Luiz Costa Tobias Pinto

Source: Eduardo Luiz Costa Tobias Pinto

ns indicates no statistically significant difference according to the F-test (p > 0.05); *, **, and *** indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01, and p ≤ 0.001, respectively. A, C, and E represent the effect of fertilization. B, D, and F show the response to Al doses. Means followed by different uppercase letters differ significantly (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05). The curves in panels D and F represent the fitted regression models describing the relationship between Al doses and plant height

ns indicates no statistically significant difference according to the F-test (p > 0.05); *, **, and *** indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01, and p ≤ 0.001, respectively. A, C, and E represent the effect of fertilization. B, D, and F show the response to Al doses. Means followed by different uppercase letters differ significantly (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05). The curves in panels D and F represent the fitted regression models describing the relationship between Al doses and plant height

* and *** indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.001, respectively. The curves represent the fitted regression models describing the relationship between Al doses and plant height: the blue line corresponds to unfertilized plants, and the red line corresponds to fertilized plants. Within each Al dose, means followed by different lowercase letters differ significantly between fertilization treatments (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05)

* and *** indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.001, respectively. The curves represent the fitted regression models describing the relationship between Al doses and plant height: the blue line corresponds to unfertilized plants, and the red line corresponds to fertilized plants. Within each Al dose, means followed by different lowercase letters differ significantly between fertilization treatments (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05)

n.s. indicates no statistically significant difference according to the F-test (p > 0.05); *, **, and *** indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01, and p ≤ 0.001, respectively. A, C, and E represent the effect of fertilization. B, D, and F show the response to Al doses. When a significant effect of fertilization treatments was observed, means followed by different uppercase letters differ significantly (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05). The curves in panels D and F represent the fitted regression models describing the relationship between Al doses and collar diameter

n.s. indicates no statistically significant difference according to the F-test (p > 0.05); *, **, and *** indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01, and p ≤ 0.001, respectively. A, C, and E represent the effect of fertilization. B, D, and F show the response to Al doses. When a significant effect of fertilization treatments was observed, means followed by different uppercase letters differ significantly (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05). The curves in panels D and F represent the fitted regression models describing the relationship between Al doses and collar diameter

*, **, and *** indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01, and p ≤ 0.001, respectively. The curves represent the fitted regression models describing the relationship between Al doses and collar diameter: the blue line corresponds to unfertilized plants, and the red line corresponds to fertilized plants. Within each Al dose, means followed by different lowercase letters differ significantly between fertilization treatments (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05)

*, **, and *** indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01, and p ≤ 0.001, respectively. The curves represent the fitted regression models describing the relationship between Al doses and collar diameter: the blue line corresponds to unfertilized plants, and the red line corresponds to fertilized plants. Within each Al dose, means followed by different lowercase letters differ significantly between fertilization treatments (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05)

*, **, and *** indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01, and p ≤ 0.001, respectively. The curves represent the fitted regression models describing the relationship between Al doses and dry matter production: the blue line corresponds to unfertilized plants, and the red line corresponds to fertilized plants. Within each Al dose, means followed by different lowercase letters differ significantly between fertilization treatments (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05)

*, **, and *** indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01, and p ≤ 0.001, respectively. The curves represent the fitted regression models describing the relationship between Al doses and dry matter production: the blue line corresponds to unfertilized plants, and the red line corresponds to fertilized plants. Within each Al dose, means followed by different lowercase letters differ significantly between fertilization treatments (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05)

Source: Eduardo Luiz Costa Tobias Pinto

Source: Eduardo Luiz Costa Tobias Pinto

Source: Eduardo Luiz Costa Tobias Pinto

Source: Eduardo Luiz Costa Tobias Pinto

Source: Eduardo Luiz Costa Tobias Pinto

Source: Eduardo Luiz Costa Tobias Pinto

Source: Eduardo Luiz Costa Tobias Pinto

Source: Eduardo Luiz Costa Tobias Pinto

*, **, and *** indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01, and p ≤ 0.001, respectively. The curves represent the fitted regression models describing the relationship between Al doses and root fresh volume or Dickson quality index: the blue line corresponds to unfertilized plants, and the red line corresponds to fertilized plants. Within each Al dose, means followed by different lowercase letters differ significantly between fertilization treatments (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05)

*, **, and *** indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01, and p ≤ 0.001, respectively. The curves represent the fitted regression models describing the relationship between Al doses and root fresh volume or Dickson quality index: the blue line corresponds to unfertilized plants, and the red line corresponds to fertilized plants. Within each Al dose, means followed by different lowercase letters differ significantly between fertilization treatments (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05)