ABSTRACT

Water resource management is closely tied to watershed conservation and the ecosystem services it supports. This study aimed to assess temporal changes in land use and land cover in the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin and evaluate their impact on ecosystem service provision. Covering 43,683 km2 in northeastern Brazil, the basin was analyzed over a 30-year period from 1989 to 2019. Land use and land cover were mapped and classified using the semi-automatic classification plugin (SCP) with maximum likelihood classification. Categories identified included woody Caatinga vegetation, herbaceous-shrubby vegetation, water bodies, and exposed soil/urban areas. From 1989 to 2019, woody Caatinga and herbaceous-shrubby vegetation declined slightly by 3 and 2%, respectively, showing relative stability. In contrast, water bodies experienced a sharp 42% reduction, which underscores the critical role of water resource management in watershed planning. A total of 17 ecosystem services were identified, spanning regulatory, provisioning, and cultural categories. Economic valuation revealed a 24% decline in ecosystem service value - from US$1,970,640.38 in 1989 to US$1,509,825.52 in 2019 - highlighting the urgent need for effective water and land use planning to counteract the impacts of unsustainable resource use.

Key words:

water resources; multitemporal mapping; remote sensing; economic valuation

HIGHLIGHTS:

Land use changes in the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu basin, driven by human and droughts, reduce vegetation and water resources.

Reduced vegetation and water loss cut ecosystem services causing economic losses and ecological imbalance.

Urgent sustainable management is needed to restore degraded areas, conserve biodiversity, and protect ecosystem services.

RESUMO

A gestão dos recursos hídricos está intimamente ligada à conservação das bacias hidrográficas e aos serviços ecossistêmicos que elas fornecem. Este estudo teve como objetivo avaliar as mudanças temporais no uso e cobertura da terra na Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Piancó-Piranhas-Açu e analisar seus impactos na oferta de serviços ecossistêmicos. Com uma área de 43.683 km2 no Nordeste do BRASIL, a bacia foi analisada ao longo de um período de 30 anos, de 1989 a 2019. O uso e cobertura da terra foram mapeados e classificados por meio do semi-automatic classification plugin (SCP), utilizando o classificador de máxima verossimilhança. As categorias identificadas incluíram vegetação lenhosa de Caatinga, vegetação herbáceo-arbustiva, corpos d’água e áreas de solo exposto/urbanizadas. Entre 1989 e 2019, as vegetações lenhosa e herbáceo-arbustiva apresentaram quedas discretas de 3 e 2%, respectivamente, indicando relativa estabilidade. Em contraste, os corpos d’água sofreram uma redução acentuada de 42%, ressaltando o papel crítico da gestão dos recursos hídricos no planejamento das bacias hidrográficas. Foram identificados 17 tipos de serviços ecossistêmicos, abrangendo categorias de regulação, provisão e culturais. A valoração econômica apontou uma redução de 24% no valor dos serviços ecossistêmicos - de US$ 1.970.640,38 em 1989 para US$ 1.509.825,52 em 2019 - evidenciando a necessidade urgente de um planejamento eficaz do uso da terra e da água para mitigar os impactos do uso insustentável dos recursos naturais.

Palavras-chave:

recursos hídricos; mapeamento multitemporal; sensoriamento remoto; valoração econômica

Introduction

The Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin is recognized as a strategic area under Resolution No. 109/2010 of the Brazilian National Water Resources Council (Conselho Nacional de Recursos Hídricos, CNRH) (BRASIL, 2010). It contains two major reservoirs: the Coremas-Mãe d’Água system and the Armando Ribeiro Gonçalves reservoir. The main uses of water in the basin are irrigation (64.8%), aquaculture (24.0%), human consumption (8.0%), industry (1.5%), and livestock farming (1.7%) (ANA, 2018).

Located in the Caatinga biome, the region is characterized by deciduous, herbaceous-shrubby, hyperxerophilous vegetation adapted to drought conditions, shallow soils, high evapotranspiration, and irregular rainfall patterns (Ribeiro Filho et al., 2021). This vegetation plays a crucial role in providing ecosystem services such as erosion control, water regulation, and carbon storage - all of which are diminished when vegetation is disturbed (Silva et al., 2021; Mendes et al., 2025).

Land use and land cover dynamics in the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu Basin have undergone significant changes, primarily driven by the conversion of natural areas into productive systems. The expansion of irrigated fruit farming along the main watercourses - facilitated by favorable soil conditions and water availability - has been the main driver of landscape transformation (Morais et al., 2015). At the same time, the unregulated growth of shrimp farming in the lower basin has caused serious environmental impacts, including soil salinization and the contamination of water bodies by untreated effluents (Aires et al., 2019). These anthropogenic changes have posed critical threats to the region’s strategic reservoirs.

Excessive nutrient inputs from agricultural and aquaculture activities have accelerated eutrophication in the Coremas-Mãe d’Água and Armando Ribeiro Gonçalves reservoirs (Araújo et al., 2024). Concurrently, the reduction of native vegetation cover has intensified siltation in these water bodies, compromising their storage capacity and directly impacting regional water availability (Tabacchi et al., 2000; Dunn et al., 2022).

Vegetation cover plays a vital role in regulating the hydrological cycle, supporting water production, and maintaining minimum flow levels essential for ecosystem stability (Klink et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021). Analyzing the historical impacts of these changes is key to understanding current water dynamics and anticipating future effects on water storage and distribution within the basin (Zhang & Shangguan, 2016).

Rivers have long been essential to urban development, serving as sources of water, transportation routes, sewage and drainage systems, and natural defenses - thereby fostering population growth and economic prosperity (Wantzen et al., 2016). In recent years, the relationship between human activity and rivers has undergone increasing reassessment, with growing recognition of rivers as providers of critical ecosystem services vital for maintaining the balance of both natural and built environments (Charlesworth & Lees, 1999; Carter et al., 2003; Mahe et al., 2005). The valuation of ecosystem services helps quantify the benefits provided by natural systems by assigning them monetary values, which facilitates evaluation, promotes public engagement, and supports sustainable decision-making (Kubiszewski et al., 2020; Zandebasiri et al., 2023). These services include water regulation, soil fertility, and biodiversity conservation, among others (Zhou et al., 2020; Fernandes et al., 2020; Teixeira et al., 2021).

However, in semiarid regions, the ecosystem services provided by natural and secondary vegetation are often underestimated due to the scarcity of quantitative studies and appropriate assessment methodologies (Wang et al., 2022; Wei et al., 2024). Although certain functions, such as carbon storage, tend to recover rapidly, environmental policies frequently prioritize more productive biomes. This reinforces the mistaken perception that semiarid ecosystems provide fewer benefits (Araújo et al., 2022; Niemeyer & Vale, 2022).

The present study aimed to identify temporal variations in land use and land cover in the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin and assess their impacts on the provision of ecosystem services.

Material and Methods

This study was conducted in the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin, which spans a drainage area of 43,683 km2 in the semiarid region of northeastern Brazil (Figure 1A). The basin extends across the states of Paraíba (60%) and Rio Grande do Norte (40%) (Figure 1B). Data were collected over a 30-year period, from 1989 to 2019.

Location of the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin in northeastern Brazil (A) and its distribution across the states of Rio Grande do Norte (RN) and Paraíba (PB) (B). The shaded area represents the watershed boundary

According to the Köppen-Geiger classification, the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin exhibits a tropical climate (Aw) in the Upper Piancó, Alto Piranhas, and Peixe sub-basins, and a semiarid climate (BSh) in the Seridó sub-basin. High evaporation rates in the region contribute to significant water losses from reservoirs (ANA, 2018). The basin’s precipitation pattern is marked by strong interannual variability, alternating between years of regular rainfall and years of water scarcity, often resulting in droughts (Mutti et al., 2019). Annual average precipitation ranges from as low as 440 mm in the Seridó Hydrographic Unit to approximately 1,050 mm in the Piancó Hydrographic Unit (ANA, 2018).

Satellite images from Landsat 4-5 TM and Landsat 8 OLI were obtained via the Earth Explorer platform for the years 1989, 1993, 1999, 2004, 2009, 2014, and 2019 to perform a multitemporal analysis at 5-year intervals. The year 1994 was replaced by 1993 due to excessive cloud cover in the available imagery. The spectral bands used for land cover classification are detailed in Table 1.

The images were imported into QGIS version 3.10.14 to define the study area and generate true- and false-color mosaics for each year, enhancing the accuracy of the supervised classification process. Classification was performed using the semi-automatic classification plugin (SCP) with the maximum likelihood (ML) algorithm (Congedo, 2013). Spectral signatures of the training samples were verified to ensure value convergence and improve classification reliability. Color standardization followed the guidelines of the Technical Manual of Land Use published by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, IBGE) (IBGE, 2013).

To train the classification algorithm, 10 samples from each land use class were vectorized through photointerpretation of RGB compositions - corresponding to the red, green, and blue bands in both true- and false-color images - with the aid of Google Earth™ imagery. After vectorization, the spectral signatures of the samples were examined to ensure convergence toward similar values, indicating that they likely represented the same land use class (Richards & Jia, 2006). When spectral signatures were consistent, the samples were grouped into a single macro-sample for use in the classification process.

Potential ecosystem services were identified based on the land use and land cover classes characterized in the study area, following the frameworks proposed by Costanza et al. (1997), de Groot et al. (2002), and the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA, 2005). The identification process involved assessing the main activities conducted in the region - such as agriculture, livestock grazing, fishing, salt production, water supply, recreation, and food provision. From this assessment, the ecosystem functions that the watershed is capable of providing were defined.

The ecosystem service values were classified according to the land use and land cover categories identified and mapped within the watershed. Valuation was performed based on the methodologies proposed by Costanza et al. (1997) and Hu et al. (2008), as outlined in the equations below. Table 2 presents the equivalencies used, along with the estimated value per hectare per year (in USD) for each land use category.

Equivalent biomes for land use and land cover classes in the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin and their respective valuation coefficients

According to Hu et al. (2008), the total Ecosystem Services Value (ESV) can be calculated in USD using Eq. 1:

where:

ESVTOTAL - total ecosystem services value (in USD);

Ak - total area of the land use and land cover class (in ha); and,

VCk - ecosystem services value coefficient per land use class (in USD ha-1 per year).

The absolute (Eq. 2) and relative (Eq. 3) variations in ESV over the analyzed period were calculated based on the differences between the estimated values for each land use and land cover category:

where:

∆ESVabsk - absolute change in ecosystem services value for class k between 1989 and 2019 (USD);

∆ESVrelk - relative change (%) in ecosystem services value for class k between 1989 and 2019;

ESV2019k - ecosystem services value for class k in 2019; and,

ESV1989K - ecosystem services value for class k in 1989.

Results and Discussion

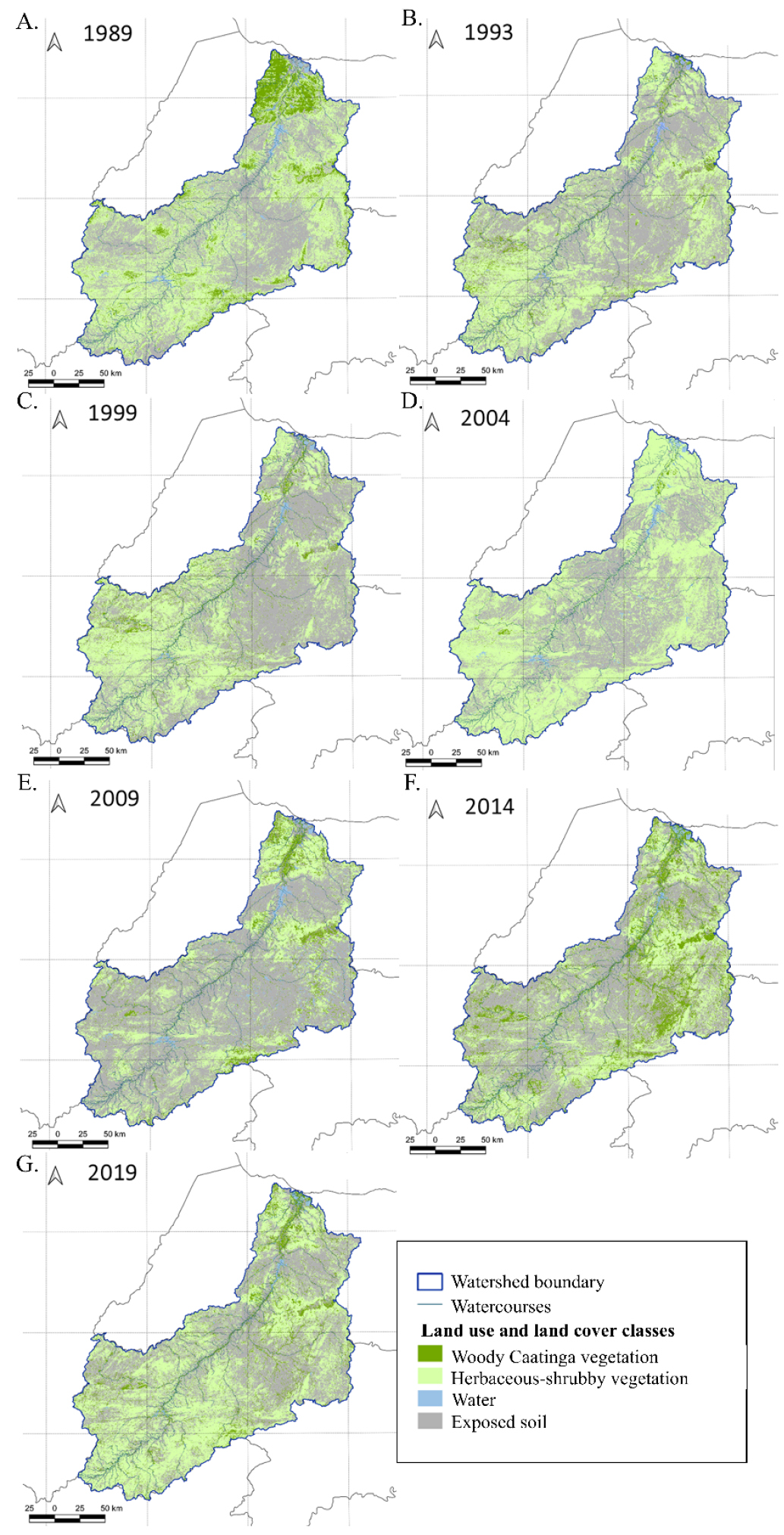

The Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin exhibited four main land use and land cover categories: woody Caatinga vegetation, herbaceous-shrubby vegetation, water bodies, and exposed soil/urban areas. These categories underwent significant changes between 1989 and 2019. Figure 2 displays the land use and land cover maps of the watershed over this 30-year period, offering a clear visual representation of the spatial and temporal dynamics across the identified classes.

Land use and land cover maps of the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin for the years: (A) 1989, (B) 1993, (C) 1999, (D) 2004, (E) 2009, (F) 2014, and (G) 2019

Images reveal consistent variations across all land use and land cover classes, with a notable decline beginning in 1989 (Figure 2A). These changes are largely attributed to irregular rainfall patterns. High precipitation levels directly influence the extent and configuration of vegetation cover - both woody Caatinga and herbaceous-shrubby vegetation - as well as water bodies. In parallel, urban expansion has intensified over the study period. In a semiarid region, this rainfall variability results in alternating periods of water abundance and scarcity (Virães & Cirilo, 2019). Episodes of intense rainfall can significantly reshape the landscape by altering vegetation patterns and expanding or shrinking water bodies, often leading to increased runoff and soil erosion. Meanwhile, ongoing urban growth disrupts natural hydrological flows and increases surface impermeability, further complicating the basin’s ecological and hydrological balance (Sousa et al., 2023; Campos et al., 2023). These transformations affect not only the ecological structure but also key hydrological processes, such as water infiltration and river discharge.

Increased rainfall can promote vegetation growth in certain areas (Figure 2D), while also triggering erosive processes and altering soil structure. Additionally, water bodies tend to undergo fluctuations in volume and hydrological behavior, increasing the risk of flooding and the emergence of new inundated areas (Sugianto et al., 2022). Simultaneously, urban expansion adds further complexity to basin dynamics (Figures 2B-G). Urbanization - typically marked by soil impermeabilization and the modification of natural watercourses - amplifies the effects of rainfall events, heightening flood risks and diminishing the recharge capacity of aquifers (Campos et al., 2023). The interplay between these factors - climate variability, changes in vegetation cover, and anthropogenic pressures - creates a dynamic and challenging scenario for the sustainable management of water resources. This underscores the need for integrated management strategies that address both environmental and socioeconomic dimensions (Mo et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022).

The frequent absence of Permanent Preservation Areas (PPAs) should be emphasized, as they play a crucial role in preventing sedimentation in rivers and reservoirs. The absence of PPAs contributes to the degradation of water resources and the loss of aquatic ecosystem integrity (Cole et al., 2020; Dunn et al., 2022).

Figure 3 shows the percentage distribution of each land use and land cover class relative to the total area of the watershed.

In the early years of analysis, herbaceous-shrubby vegetation represented the most extensive land cover class in the watershed, consistently exceeding 40% of the total area and reaching a peak of 58.7% in 2004. This category includes residual low-stature vegetation such as pastures, crops, and herbaceous cover, typically associated with shrub Caatinga formations (Macêdo et al., 2024).

Percentage distribution of land use and land cover classes in the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin from 1989 to 2019

However, over time, this vegetation class experienced a marked decline, largely driven by anthropogenic activities, including its removal for pasture establishment and the extraction of firewood to supply local ceramic industries (Silva et al., 2021). This trend underscores the urgent need for sustainable land management strategies to mitigate the adverse effects of human intervention on the watershed’s ecological integrity.

Spatially, the most critical transformations are concentrated in the lower watershed and estuarine zones, where sandy soils are highly susceptible to erosion. The increase in exposed soil observed in 1993, 1999, and 2009 - exceeding 50% coverage - reflects not only vegetation loss but also the effects of urban expansion and the exposure of bare or degraded rocky areas. These surfaces, predominantly located in the mid-to-lower sections of the watershed, present significant environmental risks. Infiltration of water in these areas intensifies erosion processes and accelerates sediment transport (Dorici et al., 2016). This spatial distribution indicates that land degradation is not uniform across the basin but is instead concentrated in areas marked by specific land-use transitions and geomorphological vulnerabilities.

The reduction in herbaceous-shrubby vegetation areas is directly linked to the expansion of exposed soil, much of which is gradually being converted into urban zones. This process highlights the urgent need for strategic planning and environmental management measures aimed at mitigating these impacts and promoting a sustainable ecological balance within the watershed (Golubiewski, 2006).

The apparent trade-off between the loss of herbaceous-shrubby vegetation and the increase in exposed soil reflects an ongoing dynamic of land conversion. Between 2004 and 2009, this trend showed a temporary reversal, marked by a resurgence of herbaceous vegetation and a reduction in exposed soils. This shift was likely driven by anomalously high rainfall levels - particularly in 2009 - which favored the rapid regrowth of short-cycle vegetation. Such vegetative responses are especially pronounced in semiarid regions, where vegetation cover is closely linked to seasonal precipitation patterns (Nehren et al., 2013; Araújo et al., 2024). Consequently, rainfall variability emerges as a critical factor not only in biomass regeneration but also in potentially masking long-term land degradation trends when analyzed through remote sensing data.

The increase in woody Caatinga vegetation observed in 2014 (15.2%) may indicate signs of ecological recovery, either through natural regeneration or reforestation initiatives. However, this trend could also be associated with a reduction in agricultural activity, particularly in the northern portion of the watershed. This area experienced significant deforestation during the 1980s and 1990s due to agrarian reform and the expansion of cashew plantations, which have since declined in response to the growing presence of wind energy projects (Fortunato Sobrinho Junior et al., 2021).

As with the observed increase in woody Caatinga vegetation, the resurgence of herbaceous-shrubby vegetation in 2019 (47.7%) appears to spatially coincide with the expansion of large-scale solar and wind energy projects. Although these developments are classified as sustainable, they have increasingly occupied areas of native vegetation and contributed to landscape fragmentation, thereby placing additional pressure on the remaining Caatinga ecosystems (Antongiovanni et al., 2020; Costa et al., 2024). This scenario highlights a paradox of sustainable development: green infrastructure projects that, if inadequately planned, undermine the very ecosystems they aim to preserve.

Table 3 presents a detailed overview of changes in both area and percentage for each land use and land cover class, highlighting the differences between the baseline year (1989) and the final year of analysis (2019). This temporal comparison offers a comprehensive perspective on the transformations that have occurred within the watershed over the three-decade study period (Rizzo et al., 2024).

Comparison of land use and land cover classes in the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin between 1989 and 2019

The analysis presented in Table 3 shows that, with the exception of the exposed soil/urban area class, all other land use and land cover categories experienced reductions between 1989 and 2019. The most significant decline occurred in water bodies, which decreased by 42% - a concerning trend that points to potential shifts in the region’s hydrological dynamics. This reduction may be attributed to factors such as land use changes, increased sediment transport from surface runoff, and diminished groundwater recharge. These processes are further linked to the series of drought events that affected the region between 1992 and 2019, particularly the prolonged and severe drought that began in 2012 and lasted until 2017, largely driven by El Niño conditions (Pereira et al., 2020; Barbosa, 2024).

This process underscores the inherent fragility of landscapes in semiarid regions, where sparse vegetation is especially vulnerable to abrupt climatic shifts and unsustainable land use, often resulting in inadequate soil coverage (Singh & Chudasama, 2021; Yang et al., 2022).

With the exception of the exposed soil/urban area class, all other land use and land cover categories showed a reduction over the study period. The areas lost from these classes were likely converted into exposed soil, either through indiscriminate use or urban expansion. This dynamic illustrates the sensitivity of semiarid landscapes to both climatic variability and anthropogenic pressure, reinforcing the urgent need for sustainable land management strategies that balance human demands with environmental conservation. Unlike humid climates, semiarid regions respond differently to environmental stressors, where limited vegetation cover and resource overuse accelerate land degradation and reduce the effectiveness of soil protection (Piscoya et al., 2018; Macêdo et al., 2024).

The Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin supports 17 distinct types of ecosystem services, which are quantified in this study. The valuation approach proposed by Costanza et al. (1997) estimates the economic value of ecosystem services using average per-hectare values derived from 16 global biomes. This methodology allows for a comprehensive assessment of the ecosystem’s contributions to human well-being, underscoring the importance of preserving and sustainably managing natural resources.

The classification of ecosystem services in this analysis primarily emphasized regulatory functions, as well as categories related to resource provision and cultural values (Table 4). This broad spectrum reflects the diversity and complexity of the services offered by the watershed ecosystem and provides a valuable foundation for future assessments and the development of sustainable management strategies.

The watershed serves as both a critical source and a key regulator of ecosystem services. The contribution of native vegetation and water bodies is particularly significant in delivering essential benefits to local populations.

Native vegetation and water areas provide a wide range of ecosystem services, including soil erosion prevention, enhanced water infiltration, biodiversity support, microclimate regulation, and groundwater recharge (Tabacchi et al., 2000; Dunn et al., 2022). They are fundamental to sustaining life, agriculture, and economic activities in the region, underscoring their indispensable role in ensuring ecological stability and community well-being. Preserving these areas is therefore vital to maintaining the long-term functionality and resilience of the watershed.

Woody Caatinga vegetation emerges as the primary provider of ecosystem services in the watershed, contributing to 16 out of the 17 identified services - equivalent to 94.12% of the total. Water bodies rank second, supporting 15 services, which corresponds to 88.24% of the services offered. Herbaceous-shrubby vegetation also plays a significant role, contributing to 13 services, or 76.47% of the total. In contrast, the exposed soil/urban area class provides only two services: rainwater regulation and provision of water for consumptive use through groundwater recharge.

Woody Caatinga vegetation provides a wide range of ecosystem benefits, including climate regulation, biodiversity conservation, and nutrient cycling. It also plays a crucial role in maintaining soil structure and regulating hydrological cycles - functions that are essential for ecological stability and resilience. In semiarid environments, woody Caatinga vegetation is particularly important, as it helps mitigate the effects of aridity, conserve water resources, and promote soil health (Singh & Chudasama, 2021). Research indicates that even under extreme drought conditions and pronounced seasonality, Caatinga demonstrates low CO2 emissions and high carbon-use efficiency, resulting in a positive carbon balance. These findings underscore the biome’s considerable potential for climate regulation, with performance comparable to that of tropical rainforests (Pereira et al., 2020; Mendes et al., 2025).

In contrast, exposed soil contributes minimally to ecosystem services and exhibits significant fragility and vulnerability. The lack of vegetative cover accelerates erosion and land degradation, limiting the soil’s ability to regulate precipitation and support groundwater recharge (Acharya et al., 2018). This highlights the urgent need for ecological restoration efforts aimed at reestablishing vegetation and safeguarding the environmental integrity of these sensitive semiarid ecosystems.

Table 5 presents the calculated results for each ecosystem service, based on the corresponding land use and land cover area (in hectares). Notably, only three of the four land use classes contributed to the total ecosystem service value of the watershed.

Among the land use and land cover classes analyzed, woody Caatinga vegetation accounted for the highest ecosystem service value. Notably, the water areas class experienced a substantial decline in value, dropping by approximately US$ 292,342.46 from 1989 to 2019. This reduction is particularly concerning, as it may signal degradation or reduced availability of critical water resources. The observed loss underscores the urgency of prioritizing conservation and restoration efforts to protect these essential ecological assets and ensure the long-term sustainability of the watershed.

In terms of relative variation, a 23.38% reduction in ecosystem service value stands out, which is particularly significant given the high per-hectare monetary value (US$ 8,498.00 ha-1 per year) associated with water bodies. Overall, the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin experienced an estimated 24% net loss in total ecosystem service value, amounting to more than US$ 460.8 million. The primary driver of this decline was the substantial reduction in water areas over the 30-year analysis period.

These findings underscore the critical importance of sustainable watershed management in preserving and enhancing the benefits provided by ecosystem services. Conservation efforts and scientific research have traditionally focused on tropical forests, often overlooking other biomes - such as semiarid ecosystems - in both policy and academic agendas (Rocha et al., 2024; Szyja, 2024). Despite being extensively altered, the Caatinga biome holds remarkable biodiversity, high biological value, and distinctive aesthetic and ecological features. Caatinga is characterized by a rich mosaic of plant communities shaped by diverse soil types and microclimatic conditions, and it hosts a significant number of rare and endemic species (Queiroz et al., 2018). Moreover, although frequently scarce and severely impacted by human activity, the biome’s water bodies are essential for maintaining ecological functions and urgently require targeted conservation measures to prevent further degradation.

Conclusions

-

Multitemporal analysis revealed moderate changes in vegetation cover between 1989 and 2019, with a 3% reduction in woody Caatinga vegetation and 2% in herbaceous-shrubby vegetation. In contrast, water bodies in the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin experienced a significant 42% decline, indicating more pronounced hydrological transformations.

-

The economic assessment of ecosystem services showed an overall reduction of approximately 24% in total monetary value-from US$ 1,970,640.38 in 1989 to US$ 1,509,825.52 in 2019. Despite a modest decline in area, woody Caatinga vegetation remained the largest contributor to total value (54.03% in 2019), while water bodies showed the most substantial proportional loss in value (-46.01%).

-

The disproportionate decline in the economic value of ecosystem services relative to the modest spatial reduction in vegetation cover underscores the importance of incorporating qualitative ecological attributes-such as functionality, resilience, and biodiversity-into sustainable management models. This is especially critical for preserving ecosystem functions in semiarid regions.

Literature Cited

-

Acharya, B. S.; Kharel, G.; Zou, C. B.; Wilcox, B. P.; Halihan, T. Woody plant encroachment impacts on groundwater recharge: a review. Water, v.10, e1466, 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10101466

» https://doi.org/10.3390/w10101466 -

Aires, J. S.; Silva, E. C.; Schramm, F.; Schramm, V. B. Analysis of a water conflict in the Piranhas-Açu river watershed. IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (SMC), p.1000-1005, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1109/SMC.2019.8914385

» https://doi.org/10.1109/SMC.2019.8914385 -

ANA - Agência Nacional de Águas. Plano de Recursos Hídricos da Bacia do Rio Piancó-Piranhas-Açu: resumo executivo. 2018. Available on: <Available on: https://bit.ly/4lq2aqe >. Accessed on: Mar 2025.

» https://bit.ly/4lq2aqe -

Antongiovanni, M.; Venticinque, E. M.; Matsumoto, M.; Fonseca, C. R. Chronic anthropogenic disturbance on Caatinga dry forest fragments. Journal of Applied Ecology, v.57, p.2064-2074, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13686

» https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13686 -

Araújo, H. F.; Garda, A. A.; Silva, W. A. D. G.; Nascimento, N. F. F.; Mariano, E. F.; Silva, J. M. C. The Caatinga region is a system and not an aggregate. Journal of Arid Environments, v.203, e104778, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2022.104778

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2022.104778 -

Araújo, I. N. F.; Cunha, K. P. V.; Cunha, G. K. G.; Matos, M. D. F. A. Environmental vulnerability applied to the territorial planning of a tropical semiarid basin. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, v.196, e730, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-024-12857-y

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-024-12857-y -

Barbosa, H. A. Understanding the rapid increase in drought stress and its connections with climate desertification since the early 1990s over the Brazilian semi-arid region. Journal of Arid Environments , v.222, e105142, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2024.105142

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2024.105142 - BRASIL. Ministério do Meio Ambiente e Mudança do Clima. Conselho Nacional De Recursos Hídricos. Resolução CNHR nº109, de 13 de abril de 2010. Brasília: Diário Oficial da União, 2010. 7p.

-

Campos, B. C. S.; Lucena, L. R. F., Righetto, A. M.; Araújo, P. V. N. Evaluation of the impact of variable recharge in an urban aquifer associated with land use and occupation. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, v.124, e104283, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2023.104283

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2023.104283 -

Carter, J.; Owens, P. N.; Walling, D. E.; Leeks, G. J. L. Fingerprinting suspended sediment sources in a large urban river system. Science of the Total Environment, v.314, p.513-534, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-9697(03)00071-8

» https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-9697(03)00071-8 -

Charlesworth, S. M.; Lees, J. A. The distribution of heavy metals in deposited urban dusts and sediments, coventry. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, v.21, p.97-115, 1999. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006694400288

» https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006694400288 -

Cole, L. J.; Stockan, J.; Helliwell, R. Managing riparian buffer strips to optimise ecosystem services: A review. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, v.296, e106891, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.106891

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.106891 - Congedo, L. Semi-automatic classification plugin for QGIS. Sapienza Università, v.1, p.1-25, 2013.

-

Costa, D. P.; Lentini, C. A.; Cunha Lima, A. T.; Duverger, S. G.; Vasconcelos, R. N.; Herrmann, S. M.; Rocha, W. J. F. All deforestation matters: Deforestation alert system for the Caatinga Biome in South America’s tropical dry forest. Sustainability, v.16, e9006, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16209006

» https://doi.org/10.3390/su16209006 -

Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Van Den Belt, M. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature, v.387, p.253-260, 1997. https://doi.org/10.1038/387253a0

» https://doi.org/10.1038/387253a0 -

Dorici, M.; Costa, C. W.; de Moraes, M. C. P.; Piga, F. G.; Lorandi, R.; de Lollo, J. A.; Moschini, L. E. Accelerated erosion in a watershed in the southeastern region of Brazil. Environmental Earth Sciences, v.75, e1301, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-016-6102-7

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-016-6102-7 -

Dunn, R. M.; Hawkins, J. M. B.; Blackwell, M. S. A.; Zhang, Y.; Collins, A. L. Impacts of different vegetation in riparian buffer strips on runoff and sediment loss. Hydrological Processes, v.36, e14733, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.14733

» https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.14733 -

Farber, S.; Costanza, R.; Childers, D. L.; Erickson, J. O. N.; Gross, K.; Grove, M.; Wilson, M. Linking ecology and economics for ecosystem management. Bioscience, v.56, p.121-133, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2006)056[0121:LEAEFE]2.0.CO;2

» https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2006)056[0121:LEAEFE]2.0.CO;2 -

Fernandes, G. W.; Arantes-Garcia, L.; Barbosa, M.; Barbosa, N. P. U.; Batista, E. K. L.; Beiroz, W.; Resende, F. M.; Abrahão, A.; Almada, E. D.; Alves, E.; Alves, N. J.; Angrisano, P.; Arista, M.; Arroyo, J.; Arruda, A. J.; Bahia, T. de O.; Braga, L.; Brito, L.; Callisto, M.; Silveira, F. A. O. Biodiversity and ecosystem services in the Campo Rupestre: A road map for the sustainability of the hottest Brazilian biodiversity hotspot. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation, v.18, p.213-222, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecon.2020.10.004

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecon.2020.10.004 -

Fortunato Sobrinho Junior, M.; Hernandez, M. C. R.; Amora, S. S. A.; Morais, E. R. C. Perception of environmental impacts of wind farms in agricultural areas of Northeast Brazil. Energies, v.15, e101, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15010101

» https://doi.org/10.3390/en15010101 -

Golubiewski, N. E. Urbanization increases grassland carbon pools: effects of landscaping in Colorado’s Front Range. Ecological Applications, v.16, p.555-571, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2006)016[0555:UIGCPE]2.0.CO;2

» https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2006)016[0555:UIGCPE]2.0.CO;2 -

Groot, R. S.; Wilson, M. A. B.; Boumans, R. M. J. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecological Economics, v.41, p.393-408, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00089-7

» https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00089-7 -

Hu, H.; Liu, W.; Cao, M. Impact of land use and land cover changes on ecosystem services in Menglun, Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment , v.146, p.147-156, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-007-0067-7

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-007-0067-7 -

IBGE - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Manual Técnico de Uso da Terra. 2013. Available on: <Available on: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv81615.pdf >. Accessed on: Mar. 2025.

» https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv81615.pdf -

Klink, C. A.; Sato, M. N.; Cordeiro, G. G.; Ramos, M. I. M. The role of vegetation on the dynamics of water and fire in the Cerrado ecosystems: implications for management and conservation. Plants, v.9, e1803, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9121803

» https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9121803 -

Kubiszewski, I.; Costanza, R.; Anderson, S.; Sutton, P. The future value of ecosystem services: Global scenarios and national implications. In: Ninan, K. N. Environmental Assessments: Scenarios, Modelling and Policy, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2020. p.81-108. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788976879.00016

» https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788976879.00016 -

Macêdo, M. S.; Menezes, B. S.; Ledru, M. P.; Mas, J. F.; Silva, F. K. G.; Carvalho, C. E.; Costa, R. C.; Zandavalli, R. B.; Soares, A. A.; Araújo, F. S. Everything’s not lost: Caatinga areas under chronic disturbances still have well-preserved plant communities. Journal of Arid Environments , v.222, e105164, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2024.105164

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2024.105164 -

Mahe, G.; Paturel, J. E.; Servat, E.; Conway, D.; Dezetter, A. The impact of land use change on soil water holding capacity and river flow modelling in the Nakambe River, Burkina-Faso. Journal of Hydrology, v.300, p.33-43, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2004.04.028

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2004.04.028 - MEA. Millennium ecosystem assessment. Ecosystems and human well-being: Biodiversity synthesis. World Resource Institute, 2005.

-

Mendes, K. R.; Oliveira, P. E.; Lima, J. R. S.; Moura, M. S.; Souza, E. S.; Perez-Marin, A. M.; Menezes, R. S. The caatinga dry tropical forest: a highly efficient carbon sink in South America. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, v.369, e110573, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2025.110573

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2025.110573 -

Mo, L.; Zanella, A.; Bolzonella, C.; Squartini, A.; Xu, G.-L.; Banas, D.; Rosatti, M.; Longo, E.; Pindo, M.; Concheri, G. Land use, microorganisms, and soil organic carbon: putting the pieces together. Diversity, v.14, e638, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080638

» https://doi.org/10.3390/d14080638 -

Morais, E. R.; Maia, C. E.; Gaudêncio, H. R.; Sousa, D. M. Indicadores da qualidade química do solo em áreas cultivadas com mamoeiro irrigado. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, v.19, p.587-591, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v19n6p587-591

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v19n6p587-591 -

Mutti, P. R.; da Silva, L. L.; Medeiros, S. D. S.; Dubreuil, V.; Mendes, K. R.; Marques, T. V.; Bezerra, B. G. Basin scale rainfall-evapotranspiration dynamics in a tropical semiarid environment during dry and wet years. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, v.75, p.29-43, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2018.10.007

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2018.10.007 -

Nehren, U.; Kirchner, A.; Sattler, D.; Turetta, A. P.; Heinrich, J. Impact of natural climate change and historical land use on landscape development in the Atlantic Forest of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, v.85, p.497-518, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0001-37652013000200004

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0001-37652013000200004 -

Niemeyer, J.; Vale, M. M. Obstacles and opportunities for implementing a policy-mix for ecosystem-based adaptation to climate change in Brazil’s Caatinga. Land Use Policy, v.122, e106385, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106385

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106385 -

Pereira, M. P. S.; Mendes, K. R.; Justino, F.; Couto, F.; da Silva, A. S.; da Silva, D. F.; Malhado, A. C. M. Brazilian dry forest (Caatinga) response to multiple ENSO: The role of Atlantic and Pacific Ocean. Science of the Total Environment , v.705, e135717, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135717

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135717 -

Piscoya, V. C.; Singh, V. P.; Cantalice, J. R. B.; Guerra, S. M. S.; Cunha Filho, M.; Ribeiro, C. dos S.; Araújo Filho, R. N. de; Luz, E. L. P. da. Riparian buffer strip width design in semiarid watershed Brazilian. Journal of Experimental Agriculture International, v.23, p.1-7, 2018: https://doi.org/10.9734/jeai/2018/41471

» https://doi.org/10.9734/jeai/2018/41471 -

Queiroz, L. P.; Cardoso, D.; Fernandes, M. F.; Moro, M. F. Diversity and evolution of flowering plants of the Caatinga Domain. In Silva, J. M. C. da; Leal, I. R.; Tabarelli, M. Caatinga: the largest tropical dry forest region in South America. Berlin: Springer, 2018. Cap.2, p.23-63. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68339-3_2

» https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68339-3_2 -

Ribeiro Filho, J. C.; Andrade, E. M.; Palácio, H. A. Q.; Moura, M. M. S.; Santos, D. L. Carbon stock of the herbaceous layer under different plant cover in fragments of Caatinga. Revista de Ciências Agronômicas, v.52, e20196916, 2021. https://doi.org/10.5935/1806-6690.20210005

» https://doi.org/10.5935/1806-6690.20210005 - Richards, J. A.; Jia, X. Clustering and unsupervised classification. In: Richards, J. A.; Jia, X. Remote sensing digital image analysis, Berlin: Springer , 2006. Cap.8, p.256-258.

-

Rizzo, F. A.; Santos, A.; Cunha, D. C. Técnicas de geoprocessamento aplicadas para análise temporal do microclima na bacia hidrográfica do córrego do Pequiá, Maranhão. Boletim Goiano de Geografia, v.44, e78032, 2024. https://doi.org/10.5216/bgg.v44i1.78032

» https://doi.org/10.5216/bgg.v44i1.78032 -

Rocha, W. J. S. F.; Vasconcelos, R. N.; Costa, D. P.; Duverger, S. G.; Lobão, J. S. B.; Souza, D. T. M.; Herrmann, S. M.; Santos, N. A.; Rocha, R. O. F.; Ferreira-Ferreira, J.; Oliveira, M.; Barbosa, L. S.; Cordeiro, C. L.; Aguiar, W. M. Towards uncovering three decades of LULC in the Brazilian drylands: Caatinga biome dynamics (1985-2019). Land, v.13, e1250, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13081250

» https://doi.org/10.3390/land13081250 -

Silva, T. J. R. D.; Leite, J. C. A.; Cavalcanti, A. K. G.; Dantas, J. S.; Sousa, F. D.; Nascimento, M. D.; Santos, L. D. A. Análise da susceptibilidade à erosão hídrica em uma bacia hidrográfica do semiárido brasileiro. Revista Brasileira de Geografia Física, v.14, p.1443-1457, 2021. https://doi.org/10.26848/rbgf.v14.3.p1481-1495

» https://doi.org/10.26848/rbgf.v14.3.p1481-1495 -

Singh, P. K.; Chudasama, H. Pathways for climate change adaptations in arid and semi-arid regions. Journal of Cleaner Production, v.284, e124744, 2021. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124744

» https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124744 -

Sousa, L. B.; Montenegro, A. A. A.; Silva, M. V.; Almeida, T. A. B.; Carvalho, A. A.; Silva, T. G. F.; Lima, J. L. M. P. Spatiotemporal analysis of rainfall and droughts in a semiarid basin of Brazil: land use and land cover dynamics. Remote Sensing, v.15, e2550, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15102550

» https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15102550 -

Sugianto, S.; Deli, A.; Miswar, E.; Rusdi, M.; Irham, M. The effect of land use and land cover changes on flood occurrence in Teunom Watershed, Aceh Jaya. Land, v.11, e1271, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081271

» https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081271 -

Szyja, M. Impact of anthropogenic disturbance on ecosystem engineers and consequences for dry tropical forest regeneration in the Caatinga. 1.ed. Kaiserslautern: UKL, 2024. 280p. https://doi.org/10.26204/KLUEDO/8204

» https://doi.org/10.26204/KLUEDO/8204 -

Tabacchi, E.; Lambs, L.; Guilloy, H.; Planty-Tabacchi, A. M.; Muller, E.; Décamps, H. Impacts of riparian vegetation on hydrological processes. Hydrological Processes , v.14, p.2959-2976, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1085(200011/12)14:16/17<2959:AID-HYP129>3.0.CO;2-B

» https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1085(200011/12)14:16/17<2959:AID-HYP129>3.0.CO;2-B -

Teixeira, H. M.; Bianchi, F. J. J. A.; Cardoso, I. M.; Tittonell, P.; Peña-Claros, M. Impact of agroecological management on plant diversity and soil-based ecosystem services in pasture and coffee systems in the Atlantic forest of Brazil. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment , v.305, e107171, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.107171

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.107171 -

Virães, M. V.; Cirilo, J. A. Regionalization of hydrological model parameters for the semi-arid region of the northeast Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Recursos Hídricos, v.24, e49, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1590/2318-0331.241920180114

» https://doi.org/10.1590/2318-0331.241920180114 -

Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Hai, X.; Shanguan, Z.; Deng, L. Driving factors of ecosystem services and their spatiotemporal change assessment based on land use types in the Loess Plateau. Journal of Environmental Management, v.311, e114835, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114835

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114835 -

Wantzen, K. M.; Ballouche, A.; Longuet, I.; Bao, I.; Bocoum, H.; Cissé, L.; Chauhan, M.; Girard, P.; Gopal, B.; Kane, A.; Marchese, M. R.; Nautiyal, P.; Teixeira, P.; Zalewski, M. River Culture: An eco-social approach to mitigate the biological and cultural diversity crisis in riverscapes. Ecohydrology and Hydrobiology, v.16, p.7-18, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecohyd.2015.12.003

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecohyd.2015.12.003 -

Wei, R.; Fan, Y.; Wu, H.; Zheng, K.; Fan, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, J. The value of ecosystem services in arid and semi-arid regions: A multi-scenario analysis of land use simulation in the Kashgar region of Xinjiang. Ecological Modelling, v.488, e110579, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2023.110579

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2023.110579 -

Yang, D.; Yang, Y.; Xia, J. Hydrological cycle and water resources in a changing world: A review. Geography and Sustainability, v.2, p.115-122, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2021.05.003

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2021.05.003 -

Yang, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Dong, X.; Liu, Y. Vegetation dynamics influenced by climate change and human activities in the Hanjiang River Basin, central China. Ecological Indicators, v.145, e109586, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109586

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109586 -

Zandebasiri, M.; Goujani, H. J.; Iranmanesh, Y.; Azadi, H.; Viira, A. H.; Habibi, M. Ecosystem services valuation: a review of concepts, systems, new issues, and considerations about pollution in ecosystem services. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, v.30, p.83051-83070, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-28143-2

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-28143-2 -

Zhang, Y. W.; Shangguan, Z. P. The change of soil water storage in three land use types after 10 years on the Loess Plateau. Catena, v.147, p.87-95, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2016.06.036

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2016.06.036 -

Zhou, J.; Wu, J.; Gong, Y. Valuing wetland ecosystem services based on benefit transfer: A meta-analysis of China wetland studies. Journal of Cleaner Production , v.276, e122988, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122988

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122988

Data availability

There are no supplementary documents.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

19 Sept 2025 -

Date of issue

Dec 2025

History

-

Received

11 Aug 2024 -

Accepted

04 July 2025 -

Published

16 July 2025

Impacts of land use and land cover on ecosystem services in the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin

Impacts of land use and land cover on ecosystem services in the Piancó-Piranhas-Açu River Basin

Source: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE. Geographic Projection System: SIRGAS 2000, Zone 24S

Source: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE. Geographic Projection System: SIRGAS 2000, Zone 24S