Abstract

This article investigates the significance of access to higher education for a group of beneficiaries of a governmental scholarship scheme (ProUni) studying at the Catholic University of Rio (PUC-Rio). It investigates the different senses of access to higher education for these scholars, the different meanings of the ProUni in their educational careers, and how their motivations are related to their decision to carry out their studies at PUC-Rio. The analysis is carried out in dialogue with Bourdieu's concept of symbolic capital and informational capital. Using questionnaires and interviews, the article indicates how scholars guide and direct their access to higher education, in some cases changing institutions in order to guarantee the quality of their education and to increase their chances of upward mobility.

Key Words:

ProUni; university students; informational capital; higher education

Resumo

A partir de questionários e entrevistas com bolsistas do ProUni da PUC-Rio, o presente artigo investiga, à luz dos conceitos de capital simbólico e capital informacional de Bourdieu, qual o sentido dado ao ingresso no ensino superior por esses bolsistas, os diferentes significados assumidos pelo ProUni em suas trajetórias e como suas motivações se relacionam com a escolha da PUC-Rio. O trabalho indica como os bolsistas orientaram seu ingresso no ensino superior e, alguns casos, mudaram de instituição de forma a garantir a qualidade de sua formação e aumentar as possibilidades de ascensão social.

Palavras-chave:

ProUni; estudantes universitários; capital informacional; ensino superior

Introduction

One of the characteristics of higher education in Brazil is that it is relatively young, the first university having been founded in 1934. Brazilian higher education has developed into a complex system of public (federal, state and municipal) and private (religious, communal, philanthropic and private for-profit) institutions. In terms of academic organization, institutions are divided into universities, university centres and non-university institutions (colleges and polytechnics). Unlike the private universities that cater to 75% of all undergraduates in the country (INEP/MEC 2014INEP/MEC. 2014. Censo da educação superior 2013. Brasília: INEP/MEC, 2014. Disponível em Disponível em http://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_superior/censo_superior/apresentacao/2014/coletiva_censo_superior_2013.pdf

Acesso em: 13 nov. 2015

http://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_sup...

), the public universities do not charge fees.

Over the past two decades Brazilian higher education has passed through a series of transformations, in particular a significant increase in the number of students matriculated through an expansion of existing public institutions and the creation of new ones (Figure 1). Since 2000, affirmative action policies have been implemented in favor of poor and non-white candidates. After a number of years of polemical debate on whether race-based affirmative action was constitutional, the Federal Supreme Court declared racial quotas constitutional in 2012. In August of the same year a federal law (Lei nº 12.711/2012) was passed obliging all federal institutions of higher learning to reserve at least 50% of their places for candidates who had studied in public high schools, with quotas for "pretos" (blacks), "pardos" (mixed-race1 1 The census term pardo is used to refer to people who define themselves as between white and black. We have used the term "mixed race" to refer to this idea, although, of course, it makes no real sense, since it assumes such an unimaginable category as "pure race". ) and indigenous peoples depending on their proportional presence in the state where the institution is based according to the most recent national census figures.2 2 "Pretos", "pardos", "brancos" and "indígenas" are the "ethnic" categories used by the national census. For students in private universities, the availability of loans has been increased, and a scholarship program implemented (ProUni) for students who studied in public schools. As a result, the percentage of people in the age range of 18-24 years enrolled in universities has increased from 10.4% in 2004 to 16.3% in 2013 (IBGE 2014).

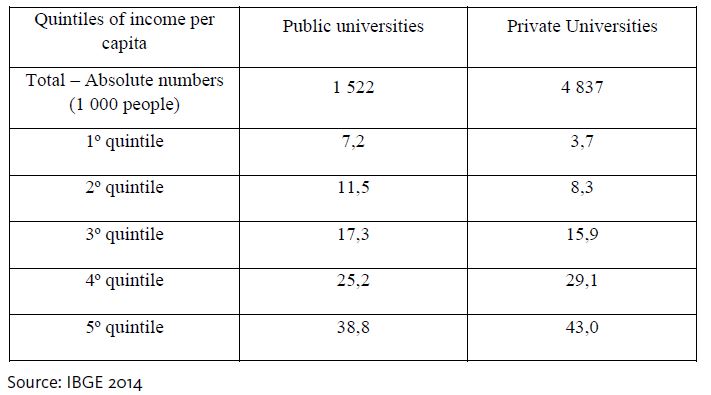

It is of particular importance that this expansion of the system has increased the number of non-white and poor students in both the pubic and private universities. Between 2004 and 2013, students from the wealthiest quintile ceased to be the majority in all universities. In 2004 they occupied 55,0% and 68,9% of places in public and private universities respectively. In 2013, these percentages had fallen to 38,8% and 43,0%, respectively (Figure 2). In the same period, students from the lowest quintile increased from 1,7% to 7,2% in the public universities and from 1,3% to 3,7% in the private ones (IBGE 2014HONORATO, Gabriela de Souza. 2005. Estratégias coletivas em torna da formação universitária:status, igualdade e mobilidade entre desfavorecidos. Mphil dissertation in Sociology, Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Sociais, IFCS, UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro.). It is important to note that in absolute numbers there are more poor and black students in the private universities whose overall intake is co much greater than that of the public universities.

Students in public and private universities according to the income per capita quintiles of their families, 2013

Even so, and largely because of the small number of university places, profound differences in wealth of students' families persist. (Figure 2). Sampaio (2000SAMPAIO, Helena. 2000. O ensino superior no Brasil: o setor privado. São Paulo, Fapesp/Hucitec. ) and Vargas (2009VARGAS, Hustana Maria. 2008. Represando e distribuindo distinção: a barragem do ensino superior.. Doctoral Thesis in Education, PUC-Rio. Rio de Janeiro.) have observed that greatest differences of wealth are related more to university courses than the institutions themselves. As far as colour or race are concerned, the percentage of white students in the 18-24 age range in 2013 was 23.5% and that of non-whites was only 10,8% (IBGE op. cit.). Poorer and non-white students continue to predominate in lower prestige courses such as teacher training courses, while wealthier students who can afford to study in high quality private high schools are able to win places in the more prestigious courses such as industrial design, medicine, communications and engineering in the non fee-paying public universities. They are also able to afford the better courses in the private universities.

The ProUni

As part of their strategy to expand higher education, the government of the Workers' Party which claims to represent various social movements and which is dedicated to reducing social inequality, introduced an affirmative action policy for the private universities in 2005; the University For All Programme (Port: Programa Universidade para Todos, ProUni). In total, one thousand and four hundred institutions of higher education - over 70% of private institutions in the country - have made scholarships available through the Programme (Programa 2010).

The ProUni (Brasil 2005BRASIL. Lei nº 11.096, de 13 de jan. de 2005. Institui o Programa Universidade para Todos - ProUni, regula a atuação de entidades beneficentes de assistência social no ensino superior altera a Lei nº 10.891, de 9 de julho de 2004, e dá outras providências. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www2.camara.gov.br/legin/fed/lei/2005/lei-11096-13-janeiro-2005-535381-norma-pl.html

Acesso em: 10 de jun. de 2009.

http://www2.camara.gov.br/legin/fed/lei/...

) concedes full and partial scholarships for students enrolled at undergraduate and advanced vocational courses in private institutions of higher education. These institutions, in turn, are liable to certain tax exemptions. For philanthropic private institutions, which already benefitted from tax exemptions, the Programme is mandatory. In order to enrol in the Programme, students must have: (a) obtained at least 450 points in the National Secondary School Exam (Exame Nacional de Ensino Médio, ENEM); (b) a per capita family income no greater than one and a half times the minimum wage (for full scholarships) or three times the minimum wage (partial scholarships); and, lastly, (c) attended a public secondary school or a private secondary school on a scholarship (Brasil 2005). The Programme also reserves some scholarships for people with physical disabilities, blacks, Indigenous or mixed-race (pardos) students, so long as they meet the other requirements. As in the case of racial quotas mentioned earlier, the percentage of scholarships follows the relative percentage presence of "pretos", "pardos" and "indígenas" in the state where the institution is based.

Since its inception, the ProUni has enabled over 900,000 scholarship students to access higher education (Brasil 2013 _________. 2013.Tribunal de Contas da União. Relatório de Monitoramento. Processo no TC 000.997/2013-7. Relator Ministro José Jorge. Brasília: TCU. Disponível em:http://portal2.tcu.gov.br/portal/page/portal/TCU/comunidades/programas_governo/areas_atuacao/educacao/Monitoramento%20Prouni.pdf Acesso em 10 de setembro de 2014.

http://portal2.tcu.gov.br/portal/page/po...

). Despite its contributions to widening university access, it provides no guarantee as to the quality of the participating institutions and the courses that they offer. It thus falls short on one of the key factors in the effective democratization of higher education. According to the Operational Audit Report of the Federal Court of Accounts (Brasil 2009___________. 2009. Tribunal de Contas da União. Relatório de auditoria operacional: Programa Universidade para Todos (ProUni) e Fundo de Financiamento ao Estudante do Ensino Superior (FIES). Relator Ministro José Jorge. Brasília: TCU. Disponível em:

http://portal2.tcu.gov.br/portal/page/po...

), 34.6% of all courses that were registered with the Programme in 2008 had never been evaluated by the National Exam of Student Performance (Exame Nacional de Desempenho de Estudantes,ENADEENADE. 2006. Relatório da IES (PUC-Rio). Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.inep.gov.br/enade

Acesso em: 9 mai. 2010

http://portal.inep.gov.br/enade...

), and 20.9% of those that had obtained a failing grade. Ten years after the creation of the Programme, no steps have been taken to heed one of the main recommendations of the Federal Court of Accounts: that tax exemptions not be conceded to courses which have ranked negatively. The Report further warns of the dangers of educating a large number of students in courses which are proven to be of low quality.

In a study of ProUni scholars enrolled in what he calls "substandard courses", Almeida (2012______________. 2012. Ampliação do acesso ao ensino superior privado lucrativo brasileiro: um estudo sociológico com bolsistas do ProUni na cidade de São Paulo. Doctoral Thesis in Sociology, Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo (USP), São Paulo.) questions their chances for upward mobility:

[...]These subgroups of scholars, many of whom are studying for licentiate degrees or attending technical courses, and a few studying for bachelor degrees in administration [...] have a less realistic chance of sustainable upward mobility, considering the notoriously low quality of the courses and universities in which they are enrolled. For these scholars, the diploma has only an instrumental value - important, no doubt [...], for there is still an advantage in having a degree in higher education - but an educational title with no greater symbolic distinction from the certificates that they will obtain after the end of their course (ALMEIDA, op. cit: 2007).

This matter is particularly important when we consider that ProUni scholars are, in general, the first in their families to attend higher education. They have therefore less experience with which to evaluate the quality of different courses when faced with the heterogeneity of the Brazilian system of higher education.

In my Master's dissertation (Santos 2011SANTOS, Clarissa Tagliari. 2011. A chegada ao ensino superior: o caso dos bolsistas do ProUni da PUC-Rio. Mphil dissertation in sociology and anthropology, Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Sociais, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro.), I analysed the difficulties encountered by ProUni scholars who must maintain themselves at university, and trace their careers prior to enrolling in institutions of higher education. I begin this article by providing a socio-economic profile of the students sampled, before presenting results on the role of the ProUni in the careers of 15 scholars up until the start of higher education. I then turn to an in-depth investigation of the factors that favoured their enrolment in the Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio), a private, philanthropic institution which is among the best universities in the country3 3 PUC-Rio only offers full ProUni scholarships, since students with partial scholarships would find it difficult to cover the costs not included in the ProUni Programme. . The hypothesis I will pursue is that these students benefitted from a certain "informational" cultural capital in understanding the hierarchies that distinguish institutions in terms of academic quality and social prestige.

Methodology

Research was based on a questionnaire distributed4 4 Since the identity and contact information of ProUni scholars is confidential, I relied on help from PUC-Rio's Dean of Community Relations in order to distribute the questionnaires. in 2010 to ProUni scholars studying Business Administration (henceforth Administration), Law and Psychology. This provided information on the socio-economic profile of these students, as well as on diverse aspects of campus life. In total, 163 scholars voluntarily replied to the questionnaire, a sample covering freshmen in six consecutive years (2005-2010). These scholars were distributed among the three courses as follows: 38 in Administration, 85 in Law and 40 in Psychology (Table 1).

The ProUni requires that scholarship distribution be proportional to fee-paying students enrolled in the course. There were thus few ProUni scholars in courses which traditionally receive a greater number of low-income students (Licentiate Degrees and Social Services). It was thus decided to restrict the investigation to courses that occupy prestigious positions in the hierarchy of careers and which reveal differences in the sociocultural level of students.

Psychology and Law were selected because they have a high number of ProUni scholars and share certain features in relation to the individual and family characteristics of the student body (ENADE 2006ENADE. 2006. Relatório da IES (PUC-Rio). Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.inep.gov.br/enade

Acesso em: 9 mai. 2010

http://portal.inep.gov.br/enade...

). Since not all scholars enrolled in these courses replied to the questionnaires, a third course was included in the sample. As the end of the semester was approaching, we selected Administration, the course with the highest number of ProUni scholars nationwide and the second-highest number of scholars in PUC-Rio.

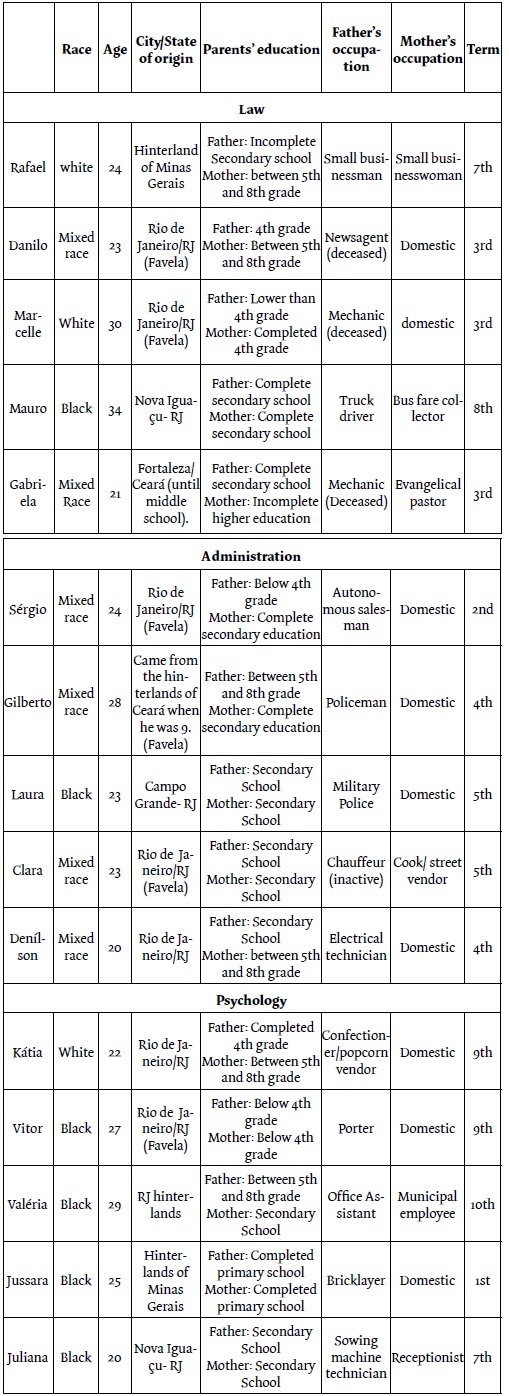

Using contact information volunteered by the respondents, five scholars from each course were selected for individual interviews, conducted at the campus. The choice of interviewees took into account race, sex, age, parents' education and the difficulties reported in the questionnaires. Interviews were recorded with the scholars' consent and transcribed.

Socio-economic profile of ProUni scholars

For the three degree courses analysed in our research, most ProUni scholars were female. The proportion was 75.5% in Psychology (n=30), 63% in Administration (n=24) and 55% in Law (n=47).

Almost 80% of the scholars in our sample fall into the two youngest age sets (Table 2). 52% of the Law scholars, 42% of those in Administration and 40% in Psychology fall into the first set, which indicates a school career with few setbacks followed by entry into university immediately after high school. Most of the scholars in the ideal age set (up to 24 years old) are studying Administration (92%) or Psychology (80%). Law, in contrast, has the highest proportion of students in the youngest age set as well as most over the age of 25.

The significant presence of young students in the three degree courses suggests an uneventful career in compulsory education followed by the immediate start of university. This data, along with information obtained in interviews, suggest that, in many cases, the ProUni presented itself as an easy route for the immediate or almost immediate transition from secondary school to university.

In what pertains to race or colour of the scholars, Psychology is evenly distributed between whites (30%), blacks (30%) and mixed-race (40%) students. In Administration and Law, white scholars are the majority, with a high number of scholars declaring themselves to be mixed-race (39,5% and 40%, respectively), and a lower number of people declaring themselves to be blacks, indigenous and yellow (Table 3).

We next present data on the education of the scholars' mothers. We can see that most of the mothers of scholars in all three degree courses have completed secondary school. For Administration and Psychology, mothers who attended school up until the first or fourth grade come second, totalling 15.8% (n=6) and 25% (n=10). It is noteworthy that 52.5% of the mothers of scholars studying Psychology attended primary school only. For Administration, the proportion is likewise high at 36.8%. Law displays the largest percentage of mothers who completed their higher education (Table 3)

It can thus be asserted that Psychology scholars come from families with mothers possessing low cultural capital, while those studying Administration are in an intermediary position vis-à-vis the other two degree courses. There are indications that Law students come from a more privileged background.

We now present the occupation of scholars' fathers5 5 There are a high proportion of mothers in the three degree courses who do not engage in any form of waged labour and fall into the 'housewife' category. These are 41% of the mothers studying Psychology, 39% in Administration and 35,4% in Law. , a classic operational construct for the identification of the position of an individual in the social structure. We use the socio-economic scale elaborated by Hasenbalg and Silva (1999HASENBALG, Carlos; SILVA, Nelson do Valle. 1999. "Educação e diferenças raciais na mobilidade ocupacional no Brasil". In: Carlos Hasenbalg; Nelson do Valle Silva; Márcia Lima (orgs.), Cor e estratificação social. Rio de Janeiro: Contra Capa. pp. 217-230.), composed of six occupational subgroups corresponding to six different socio-economic statuses: high (professionals with higher education degrees and high-net-worth individuals); upper medium (medium-level professionals and affluent individuals); medium-medium (non-manual workers, low-level professionals and well-off individuals), lower medium (qualified and semi-qualified workers), upper low (unqualified urban workers) and lower low (unqualified rural workers).

In our research, the two lower-status strata were grouped together in a single index, simply termed 'low'. This is justified due to the small number of candidates in the lower low stratum in our sample. When information on the father's occupation was not obtained we used information on the mother's occupation. Instances in which we were unable to obtain any information concerning the parents' occupation were considered "missing cases".

The data concerning the father's occupation indicate that fathers of ProUni scholars tend to fall in the medium medium and lower medium strata. Administration and Law scholars tend to have fathers in the medium medium strata (43% and 42% respectively). For Psychology scholars, in contrast, only 25% of fathers fall into the medium medium stratum. In Law, the second highest percentage of fathers are in the lower medium strata (27.8%). In Administration, the lower medium and low strata account for the second largest percentage, each one at 21.6%. Fathers of Psychology scholars tend to be in occupations with low social prestige and income, with a high percentage (42.5%) of fathers falling into the lower medium stratum. When this percentage is added to the 22.5% of fathers that fall into the low stratum, we have a total of 65% of fathers of Psychology scholars working manual jobs. For Law scholars only a small proportion of fathers are in the low strata, expressing a tendency for a better education and higher income.

Our sample shows marked differences in the distribution of students among the three degree courses based on the school system attended in secondary school6

6

Compulsory education in Brazil is organized in three stages: Pre-school (0 to 5 years of age), basic education (06 to 14 years of age) and secondary education (15 to 17 years of age). Graduation at the end of secondary school is a precondition for entering higher education. Techincal education can be followed at the same time as, or after, secondary education.

(Table 6). In Brazil, graduates from federal or private schools have considerably greater chances of continuing on to university when compared with students from other public schools, even when we allow for variables such as class, race and gender (Ribeiro 2010PROGRAMA cria 4 mil comissões locais para acompanhamento. 14 de maio de 2010. Portal MEC. Disponível em: Disponível em:http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=15429

Acesso em 28 de maio de 2013

http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?optio...

). Type of school is hence one of the main factors determining educational inequalities. 58.7% of scholars in our sample studied in the State-level public system, with a higher proportion (75%) studying for a Psychology degree. The proportion is lower for scholars studying Law (55.3%) and Administration (48.6%). For both of these degree courses there are high numbers of scholars that graduated from private schools and even higher numbers from federal schools. This is at least partly explained by the fact that the Law and Administration courses at PUC-Rio are more competitive, with more demanding admission criteria, and are hence more rigorous in selecting candidates.

A Desire for Upward Mobility: the Institution as Symbolic Capital

For Law and Administration scholars, the two main reasons for entering higher education were "to attain a better standard of living" (respectively: 67%, n=57 and 74%, n=28) and to "improve living conditions for my family" (respectively 56.5%, n=48 and 47%, n=18). For Psychology scholars the percentage was slightly lower but still expressive: 62.5% (n=25) of Psychology scholars went to university to attain a better standard of living, while 37.5% (n=15) did so to improve their family's living conditions.

It should be noted that only for Psychology did the "chance for personal fulfilment" gather the highest proportion of answers (65%; n=26). These results thus show that, for Psychology scholars, higher education is conceived in terms of both economic improvement and personal fulfilment, while those in the other two courses tend to put economic motives first.

The academic literature on working class youths (Zago 2007____________. 2007. "Prolongamento da escolarização nos meios populares e as novas formas de desigualdades educacionais". In: Lea Pinheiro Paixão; Nadir Zago (orgs.), Sociologia da educação: pesquisa e realidade brasileira. Petrópolis: Vozes. pp. 128-153. ) has highlighted the tendency to view higher education as a means for ensuring a place in the job market, a route for occupying positions with greater prestige and better wages. The same tendency is present among the scholars in our sample, most of whom come from the medium and lower strata of society, and for whom, therefore, higher education provides an opportunity for overcoming their humble social origin.

The indication of PUC-Rio as the first choice institution of higher education also seems to be based on a desire for upward mobility7 7 The question concerning the choice of institution was formulated in such a way as to evaluate the degree of importance attributed to each of the factors in the decision-making process ("no importance/does not apply", "little importance", "very important", "most important factor"). . "Quality of teaching" was the first most common option marked as "very important" or "main reason" in the questionnaire. Other aspects of the institution's quality, such as infrastructure and social prestige, were also taken into account when choosing to study at PUC-Rio. Scholars who answered the questionnaire with "other reasons" included "Academic infrastructure, good professors, library", "Degree course excellency, Infrastructure of a private institution", "The most recognized institution", "Great structure and highly rated in the job market", "Wide acceptance of a PUC diploma in the market", "Market prestige", etc. Similarly, during interviews scholars regularly referred to PUC-Rio as a university "of renown", "well-regarded in the market", and mentioned its importance for their "CV".

Studies show that proximity to place of residence is one of the most important factors involved in choosing a university, particularly among low-income students (Almeida 2009ALMEIDA, Wilson Mesquita de. 2009. USP para todos?: estudantes com desvantagens socioeconômicas e educacionais e fruição da universidade pública. São Paulo: Musa Editora.; Portes 2007PORTES, Écio Antônio. 2007. "O trabalho escolar das famílias populares". In: Maria Alice Nogueira; Geraldo Romanelli;Nadir Zago (orgs.), Família e escola: trajetórias de escolarização em camadas médias e populares. Petropólis:Vozes. pp.99-123.; Zago 2000ZAGO, Nadir. 2000. "Quando os dados contrariam as previsões estatísticas: os casos de êxito escolar nas camadas socialmente desfavorecidas". Paidéia, 10(18): 70-80.). However, for three-quarters of all the scholars in our sample, easy access to PUC-Rio was not a determining criterion in choosing an institution of higher education. Indeed, 60% of scholars live very far from PUC-Rio's campus in the Zona Sul of Rio de Janeiro city. Most live in neighbourhoods in the Zona Norte, Zona Oeste and Baixada Fluminense, as well as in other municipalities of the State of Rio de Janeiro. For these ProUni scholars, distance is less important than the quality of the institution, though the commute remains an enormous challenge for the continuity of their education. The desire for social mobility, together with support from families and the institution8 8 PUC-Rio offers material support (e.g., transport and meals) for scholars who are less economically privileged. , are prime motivations for overcoming this challenge.

It can thus be claimed that, for the scholars in our sample, the excellence of teaching at PUC-Rio, which is directly linked to the social prestige of the institution, is recognized as symbolic capital which can enhance the value of the diploma in the job market. Although motivations of a more practical order are central to the decisions of these scholars, quality is also valued in terms of personal growth and knowledge acquisition:

(...) It's not bad-mouthing, there [referring to the institute of higher education in which she had studied] the professors were great, but in comparison, today, PUC offers a much more comprehensive education. I don't know about other colleges. It [PUC-Rio] educates you to be a citizen, it wants you to think, to criticize. In the other one I went to, no. They [the professors at PUC] offer you a much wider horizon (Marcelle, 3rd term, Law)

The importance many scholars attribute to the market value of a diploma from PUC-Rio is expressed in the fact that 13 of the scholars in our sample had attended one or even two other institutions before being accepted by PUC-Rio. Even though they had obtained a ProUni scholarship to other private institutions, these scholars asked to be transferred or, in most cases, sat the ENEM exams again to obtain the necessary scores for gaining a place at PUC-Rio. We will return to these stories shortly.

First, it is important to observe that the image of PUC-Rio as a prestige and high-quality university seems to bear little relation to the scores that the Institution obtained in the evaluations carried out by the Ministry of Education (MEC). Although some scholars consulted the Student Guide or carried out research on the internet, the main source of information for interviewees were friends, relatives, teachers or acquaintances who had studied at, or were otherwise familiar with, PUC-Rio. In some cases, a university preparatory course was also important in clarifying the alternatives available to those who could not afford tuition.

The central role of inter-personal relations in choice of institution of higher education is also manifest in the analysis of other factors influencing the decisions of the scholars sampled. "Advice of friends and/or teachers" was the second most common option marked as "very important" or "main reason" in the questionnaire. According to Bourdieu (1996BOURDIEU, Pierre. 1996. Razões práticas. São Paulo: Papirus Editora.), the social networks in which we are involved play a crucial role in affording knowledge of the education system by providing a more accurate view of the institutional context, the opportunities available and how best to navigate them. Social capital9 9 James Coleman (2000) also considers information to be a specific form of social capital, defined as aspects of the social structure that function as facilitating resources for the actions of social actors. This underscores the potential of social relations to supply the information that social action is then based on. can thus be seen as one of the means for "gathering" informational capital about the academic world. In contexts such as that of Brazilian higher education, composed of diverse types of institutions of different quality, gathering informational capital is particularly important for understanding the hierarchies that distinguish IES/degree course in terms of academic quality, social prestige and value for money. We will develop this discussion in the last section of the article, but the following passage is revealing of how a mediator-figure can open new opportunities in what pertains to choice of institution:

This matter of coming to PUC was also a surprise for me. Because my mom is in the Church. She and my dad are in a couples' group and they know a guy who worked at the Vladimir Nunes College [fictional name of a College in the Campo Grande district]. So I decided I was going to do Administration there. So he told me to do the ENEM again to see if I could get the scholarship. When the result of the ENEM came out, we went straight to him, he was sort of a sure thing for getting into university. But when he saw my results, he saw that I had scored well enough to go to PUC. PUC didn't even exist for me, it hadn't even crossed my mind. I didn't have this vision. I was just there in my own world, very Campo Grande, well within the conditions I thought I had at the time. Then when I went to register with the ProUni, I went and put PUC down as my first choice, like "let's see where this is gonna go". Then, when I was pre-selected, I didn't even believe it. I didn't even know where PUC was, I had to ask for help, find out, ask my boyfriend to bring me here. So, sort of like, one person said something and I went "ah, let's see" and came here. (Laura, 5th term Administration)

Characterization of the interviewees: opening considerations

The tables below summarizes the profile of the scholars interviewed10 10 The names of the scholars have been changed to protect their identity. and conveys something of their school careers ("Characterization of school career"). From a total of 15 interviewees, 8 are women and the majority are black or mixed-race. Most interviewees are aged 24 or under. One representative from each degree course studied at a Federal school, the remainder hailing from the State system. In alignment with the tendency observed in the quantitative data in our sample, the fathers of the interviewee did not attended higher education and hold medium-to-low prestige jobs.

It is important to highlight certain trends in the career of the interviewees that point to the importance of a good study environment from the very start of their education. The fact that many of the interviewees' mothers did not work outside the home meant that they were able to follow school routine, keeping an eye on schoolwork, attending meetings and demanding that their children obtain passing grades. In those situations in which lack of education inhibited direct intervention in schoolwork, mothers were nonetheless able to hire tutors or to otherwise stress the importance of study as a means to overcome the family's socioeconomic condition. Furthermore, scholars tend to assess their own school careers in positive terms, mentioning their "effort", "intelligence" and pointing to "the school's recognition of their quality".

The importance accorded to studying is reflected in a late entry into the job market for 10 of the 15 interviewees. These students only needed to juggle work and education once they had completed secondary school. Among those who worked during compulsory education, only Marcelle and Gilberto contributed directly to their family's income. Rafael and Clara did no paid work, only helping their parents in their own jobs. Danilo participated in a qualification programme as a bank teller, through the Salesian Centre for Teenage Workers (Centro Salesiano do Adolescente Trabalhador, CESAM), an institution that helps socially vulnerable youth. In this instance, opportunity and experience were more important than financial recompense.

This emphasis on the importance of study ensured an uneventful compulsory education for all scholars in the sample, except Gilberto, whom I will analyse at the end of this article. But school work was only intended to provide the students with better chances in the job market. It was not treated as a means to access further education. As we will see, the decision to go into higher education was generally taken after the completion of secondary school or some period of work experience.

For four scholars (Clara, Gabriela, Danilo and Juliana), the choice of private school further reiterates the concern with obtaining an education as compensation for a lack of economic and cultural capital. Although less prestigious than other private schools, they were nonetheless seen to be better than public schools. For Vitor, who lived in a favela, the process of socialization involved cutting him off from the community, keeping him "stuck in the home", a common practice in popular spaces (Souza e Silva 1999). When he went to secondary school, he decided to study in a well-regarded state school outside of the favela in which he lived:

I don't say I studied, but that I did my time there [at the school in which he finished his primary education]. [...] We would go because they gave us meals, many went just for that. Because I studied a little more, there were fights, I got beat up, bullying. Me and my nerd friends. Then when I went into secondary school, I didn't want to study near the Rocinha, I want to go far away, sort of get to know life. So I went to study in Copacabana. [...] I wanted a good school, not that thing of just going through the motions, because I didn't identify with that. (Vitor, Psychology).

A further characteristic of the interviewees is the fact that they were single, which freed them from the responsibilities of married life. This allowed some of them to stop working after secondary school in order to prepare for higher education. Marcelle is the only person in the sample who had been married and raised two children, with a demanding routine of study, work and domestic responsibilities.

Even though our sample is heterogeneous, including a mixture of working and lower middle class students, the evidence makes it clear that one or more of these elements (stress on studying, late start in the job market, good schools, continuous and uneventful education, bachelorhood) was important in providing social dispositions and conditions, so that, once our scholars were able to gather informational capital, they could choose, and gain acceptance, at PUC-Rio.

The ProUni from the perspective of student careers

In this section I analyse the role of the ProUni in the careers of the students prior to entering higher education. For analytical purposes, the interviewees were divided into two groups. The first group includes four students who sat the ENEM exams in secondary school and enrolled at PUC-Rio as ProUni scholars soon afterwards. The second group took one or two years before starting university. When given a chance to further their university career through the ProUni, these latter scholars made full use of the opportunities available, thus expressing, in an exemplary fashion, the transformation of durable dispositions - the habitus - into objective strategies. At the end of the article, I will detail their careers, since they help us understand in greater detail the crucial role of different mediators in enabling conformation to the "sense of play", to use Bourdieu's words.

In the first group of students, Kátia, Juliana and Gabriela were admitted to PUC-Rio after their first attempt at access through the ProUni programme. Denílson did not get a scholarship to his first-choice course, Law, but gained a place in Administration, being admitted into the second period of the degree. All of the people in this group graduated from federal schools renowned for their quality, which probably boosted their chances of first-time approval. The exception is Juliana, who neither studied at a federal school nor attended a preparatory course. Most of her basic education was obtained in private schools, which she attended on scholarships. She chose a state technical school for her secondary education and did not work at any time during her school career. When selecting a public school for her secondary school, Juliana considered the existence of affirmative action for graduates from the public school sector, and she sought some work experience in case she was unable to obtain a place at a university.

Kátia was the only student in this group who gained entrance to a public university. She explains why she nonetheless chose to go to PUC-Rio: "studying at PUC also helps because of its name, its CV. The UERJ often has strikes, I had gone through three strikes at the CEFET [public secondary school], I was already fed up with strikes".

Notice that the ProUni was not the only chance for a university education, not even for Gabriela and Juliana who were unable to obtain places in public institutions:

I would not get in 2007 without the ProUni, but I would have kept trying. I had a chance to go into a good university, PUC or public (Gabriela, Law scholar)

[I believe that without the ProUni I would've gotten into university] Because there are already benefits to having gone to a state school for the entrance exam [she is referring to affirmative action policies]. I would have gone to a preparatory course to train (Juliana, Psychology scholar)

These two students believe that, with a further year or two of preparation for the entrance exams, they would have won a place at a public university anyway. A ProUni scholarship thus meant not having to delay entry to higher education. It seems as if this is an expectation that is not always related to entrance exam performance. According to Denílson, in contrast, were it not for the ProUni he would have followed a technical training course in Tourism, since he only decided to enter university once the selection process for public institutions was already under way:

When we don't have a family base - in my family no one has a university education to this day - we don't even think of university. It wasn't my reality. (...) Then I thought: I either go into the job market or into a university. Then I chose to go to university. I thought of going to a public university, but I also didn't know what degree I wanted to pursue. I said: "I'll do it". I had no time to think, to prepare, not even to think of the degree, it was a last minute thing. I saw the ProUni as the only chance I had, because I hadn't registered at any public university. I said: "No, there's still the ProUni for me to try and get into a private university". (Denílson, Administration scholar).

It is common to hear from these scholars that they did not consider higher education until their last year in secondary school, either because they felt unprepared to challenge for a place, or because they had simply not planned for it. School played an important part in enrolling these students in the ENEM, which later enabled them to try for a ProUni scholarship:

I didn't want to take an entrance exam in the last year [of secondary school] because I thought I wouldn't pass if I didn't take a preparatory course. I didn't want to spend money on the exam for nothing. I didn't even ask for an exemption [from the exam fee] because I had already missed the deadline and I wasn't considering it. But my mom said I had to do it to try it out, so that next year I could make it count. I only took the entrance exam for UERJ and the ENEM, because I had to, everyone did it for the school to get evaluated, it was free. When the final period for ProUni inscriptions was approaching, a friend said that she had applied to International Relations at PUC and asked me to go with her. I went and liked the idea. I did some research and PUC was best for psychology in Rio. (Kátia, Psychology scholar).

Actually, I took the ENEM thinking I'd fail, because I hadn't even done a preparatory course. It was even because my mom insisted and because school automatically enrols all third year students in the ENEM. I then went and took it, all the while thinking I'd fail. (Juliana, Psychology scholar)

I studied, I took a technical course. Then in the last year I thought I'd try a university, but I hadn't thought about it before. But then I sat the ENEM, because the school enrolled us, and since I'd already done it I thought I'd go for the ProUni (Denílson, Administration scholar)

All of the scholars who did not transition immediately from secondary school to university graduated from state schools. All five of the scholars who worked during compulsory education also fall into this group. Except for Laura, the ProUni had not been created when these students were in school. Most never considered any route into higher education when they were in secondary school, either because they considered university inaccessible or because they had never even given it any thought, which highlights the symbolic distance between lower-class youth and higher education. It was because of difficulties encountered in the job market, such as low wages and long working hours, that these scholars began to conceive of a project for accessing higher education. The role of personal relations and siblings who were already in higher education, as well as awareness of the possibilities offered by the ProUni, all contributed to this aim:

University life began with my sister [graduated from PUC-Rio with a Social Action scholarship], she inspired me and it was through her that I went back to studying. Because until then I had been working in commerce. Before I had been in the Armed Forces. Because we have this culture that we study until secondary school. But I lived like a slave, a robot at work. At the time I started doing ENEM, if I'm not mistaken this was in the first year of ProUni, in 2004. And my mother and my sister said to me: "Do the ENEM", because I complained of how tiring it was to work in commerce. They said: "do it to see if you can change a little, don't keep living like a slave" (Gilberto, Administration scholar)

I didn't associate college with the job market in a direct way. I wanted to get into the job market. But since I saw that working was a drag, I suffered a lot as an employee, having to do things and not being allowed to have an opinion about what you're doing. It was then that I decided to go back to studying (...) Luckily, I had friend who was a teacher at a community preparatory course, we went way back, and I then started to study [at the preparatory course]. (Vitor, Psychology scholar).

For Jussara and Rafael, who come from the interior of Minas Gerais state, further education was also a chance to move to a city that offered more opportunities for upward mobility. The decision to go to university depended on the influence of acquaintances and an ex-boyfriend, for the former, and an older sister, for the latter:

I didn't do it [entrance exam in the third year of secondary school], man, I had no idea, the teachers didn't encourage it, they left students to themselves, you know? I only realised I needed to study after I finished secondary school. I spent half the year doing nothing, and I went: "Damn, I can't go on like this, what future have I got here? What am I going to do in this town? Earn minimum wage"? I said: "I'm going to study". (...) I think if she (older sister) had not left home, I wouldn't have followed. She got into university [public university in São Paulo]. I went along with her to help with enrolment. I didn't know anything, I didn't even know what the Metro was! And, well, I also saw what a university was. I got an idea. This is the problem in the interior: you don't have a university, people don't leave the interior, they just stay there, in that region, sometimes they have no idea what a university is, what it can provide for you, what you can provide for the university and for society too. I think once you leave the interior and you begin to see, you start establishing contacts, creating a different idea of how much you can contribute, how much you can absorb. (Rafael, Law scholar)

They [secondary school teachers] encouraged me to do the simulation exam in Viçosa, but I never did it, I didn't care. No, it's not that I didn't care, but I thought it was beyond my reach. I thought college was only for people with money. Because I lived deep in the interior. I never thought of myself somewhere else. Even though I wanted to go somewhere else. I thought, how am I going to leave here? How? I wanted to move, to increase my possibilities (Jussara, First Term Psychology)

When asked what made her change her mind and to try, first, for the entrance exam to public universities, and, later, the ProUni, Jussara says:

I started to see that many people did it, many people close by did it, like, a friend of a friend, and an ex-boyfriend who was in higher education and who influenced me a lot. So, doors started opening up for me. (Jussara, First Term Psychology)

These statements exemplify how the dispositions and aspirations of these young people are reoriented as new social situations present themselves. In a perspective grounded in Bourdieu's work, it is the same 'practical sense', which initially inhibited these students from "wanting the impossible", that comes to conform to new expectations in relation to further education, as the students come to realise that the university is accessible to those around them and that they are faced with new possibilities for university access through the ProUni. As Honorato (2005HONORATO, Gabriela de Souza. 2005. Estratégias coletivas em torna da formação universitária:status, igualdade e mobilidade entre desfavorecidos. Mphil dissertation in Sociology, Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Sociais, IFCS, UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro.), following Anthony Giddens, notes, graduation from secondary school is a time of intense "reflection" on economic difficulties, and a reorientation towards a university career generally follows from contact with concrete cases of access to higher education. Similarly,Mongim (2010MONGIM, Andrea Bayerl. 2010. Título universitário e prestígio social: percursos sociais de estudantes beneficiários do ProUni. Doctoral thesis in Anthropology, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói.), in her research into ProUni scholars, stresses that it is not only the construction of a plan for university entrance, but also its actualization, that takes shape through the support of mediators which can be either "personalized" (family, friends, teachers) or of a "formal-legal" type, including preparatory courses and, fundamentally, the ProUni itself.

However, decision to go into higher education is not so easily put into practice. For scholars whose passage from secondary school to higher education was indirect, the entrance exams prove to be a difficult obstacle to overcome. In this group, eight of the interviewees attempted entrance exams to public institutions, but only one was successful. According to Sotero's (2009SOTERO, Edilza Correia. 2009. Negros no ensino superior: trajetória e expectativa de estudantes de Administração beneficiados por políticas de ação afirmativa (ProUni e Cotas) em Salvador. Mphil dissertation in sociology, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo.) research, one of the reasons students opt for the ProUni is the perception that they are unprepared to compete for a place in public universities. ProUni is thus seen as a more realistic alternative for entering higher education:

I took the entrance exam once, twice, but I didn't pass. So, through the ProUni it was easier. I expected to go into higher education and study Law. ProUni made this much easier. (Mauro, Law scholar)

I thought it would be an easier way to get in. A more viable opportunity for succeeding. It was a very good opportunity, a dream come true. It was the chance of realizing what would otherwise have been impossible. (Laura, Administration scholar)

When I finished middle school, I didn't have a very wide perspective of getting into higher education. This came slowly, later, six months after I was already working in a university call centre, when I came to know the ProUni. The enrolment opened up, I did it and got into the Technical Course in Music Production. (Danilo, Law scholar).

Even though the ProUni is frequently mentioned as an easier way to obtain a place in undergraduate courses, this does not mean that acquiring the scholarship requires no further effort from the students. As the table exhibiting school careers shows, among the 11 scholars who started their undergraduate degrees later, nine of them studied at preparatory courses. In some cases, these courses are only attended for short periods of time, no more than a few months. Nonetheless, they are considered important by the scholars, either as a source of information about different ways of accessing higher education and the different institutions available (five of them found out about the ProUni scholarships to PUC-Rio through these preparatory courses), or as actual preparation for the exams.

Laura first tried for the ProUni in secondary school, but she needed to juggle the preparatory course with a further two years of work in order to obtain the scholarship. Valéria sat an entrance exam for the first time in 2003, four years after graduating. Since she did not pass, she decided to stop working and to study, even attending two preparatory courses at the same time "because I hadn't studied for four years and I needed to get everything (subjects) up to date". Since she got a grade in the 2004 ENEM, she entered PUC-Rio through the ProUni the following year.

Mauro never attended preparatory courses. To prepare he looked at past ENEM exams to get an idea of the content, and after two selection processes he got a place at the Law degree course through the ProUni. He explains why he considers that the ProUnito be an easier route into higher education:

50% of the exam, if you watch television, read a newspaper, if you're into things that are happening around you, you'll do well. Unlike the entrance exams, which require a more specific knowledge, the ENEM requires general knowledge. This certainly makes it much easier. (Mauro, Law scholar)

For Clara, the ProUni was not only an alternative to the entrance exams for public universities, which she was unable to pass. It was also the means for resuming her Administration degree after losing a ProUni scholarship at a prestigious College in Rio de Janeiro. Residing in a favela, Clara's father (like Vitor's) was concerned that she "didn't mix in", "didn't play in the streets". She claims that she decided to enter university early on, since she "didn't want the life of people around me". Studying at renowned institutions was an aim pursued by Clara and her family ever since compulsory education, though with little success. Having been selected by the ProUni for a prestigious institution is, therefore, the realization of this project:

Even if they [her parents] didn't go to university, and with all their problems, my father is very intelligent and always emphasised study. During the holidays I would stay at home, kids were playing and I was at home studying for the Pedro II [a well-regarded public school] exams. My first victory was the Administration College, but my first attempt was Pedro II. In secondary school I did [the selection process for four well-regarded schools], all exams I had to sit. I didn't get into any of those, I only got into university. I had been trying for a long time.

Speaking of the reasons for having lost the first ProUni scholarship, Clara explains that, alongside difficulties with a few of the subjects she was studying, there were also concerns of a more practical nature that affected her performance in the exams:

There was Maths I, Maths II, Statistics; it's tough, and I found it difficult. Because maths had been weak in my secondary school. I had to re-sit courses and ended up losing my scholarship. The pressure was high, it was a little complicated for me. Because there was bus fare, lunch. It was too much to take in. And sometimes we need tranquillity to sit down and study. (...) Then I came here [PUC-Rio], I'm going to graduate, it's a good school, traditional, renowned and I can breathe.

For those who never sat an exam for public institutions, there were other obstacles. While still in secondary school, Marcelle attended the Preparatory Course for Blacks and Poor (PVNC) for six months. However, she decided to delay her university plans, since she had to take care of her son and work at the same time. Four years later, in 2007, she sat an exam and got a place to a Law degree at a private university selected because of the "price" of tuition. However, after three periods she had to stop out of college because she was unable to manage the expenses.

Encouraged by her mother, she decided to try for the ProUni as a way of going back to university:

My mother saw them talking about the ENEM on television, about the ProUni. My mother said: "go, go". I didn't want to because I thought I wouldn't be able to do the exam, it had been a long time since I'd done the PVNC. All I studied was Law. (Marcelle, Third term Law)

Sérgio, an Administration scholar, only considered entering higher education through the ProUni. Two years after graduating from secondary school, he unsuccessfully tried for two ProUni selection processes, after which he decided to stop working for a year and dedicate himself to his studies at a community preparatory course. On his third attempt he put PUC-Rio down as his first choice institution, since he had obtained good grades at the ENEM exam, and even though he remained unsure of his chances: "I put PUC-Rio down as my first choice, though I didn't even think I'd get accepted, right, to be honest. In truth, I just tried my luck". Although he never attempted to gain entrance through any other means, Sérgio believes that even if the programme did not exist he would be in higher education "because I would keep studying and trying to get into public institutions and, if I didn't get in, I would try a private college. I would work to pay tuition".

The analysis of the statements of the ProUni scholars can take different meanings, which depend on their background and situation. For those who were in secondary school when the ProUni was created, it represented the possibility of not delaying the start of university. Students who were unsuccessful in the entrance exams for public institutions, or who did not consider themselves prepared to sit them, saw the ProUni as their only realistic possibility of entry into higher education. By widening the opportunities for accessing higher education, the ProUni therefore effects a transformation in the perception of students concerning their chances of reaching higher education and, above all, in their chances of achieving social mobility in a smooth manner.

It is also important to note that mothers and sisters who attended higher education play an important part in the decision process. The value that mothers attribute to education, which is initially focused on the completion of compulsory education, reveals itself to be equally fundamental in encouraging their children to sit the ENEM exams, or to resume study for those who were already in the job market. For those with sisters in higher education, these were not only a source of motivation, but, above all, a means for understanding the hierarchy of prestige of degree courses and institutions.

Discovering the sens du jeu: social networks and informational capital in choosing PUC-Rio

In what follows, I present the main factors that stimulated and made possible for four interviewees (Gilberto, Danilo, Jussara and Rafael) who were already in higher education to submit themselves to various selection processes in the ProUni in order to change institution and/or course. The biographies under consideration allow us to understand in more concrete terms some of the trends noted earlier, particularly how informational capital helps to adjust strategies in order to enable upward mobility through higher education. I note that the names of the institutions of higher education mentioned by the students have been changed.

Gilberto

Gilberto is the most atypical of the interviewees. He is the only one who entered the job market at the age of 14 and interrupted his studies while still in secondary school. His parents hail from the Northeast of Brazil, and he came to Rio from Ceará with his family so that his father could be treated for Alzheimer. His mother's dedication to his father's illness distanced her from her children's education, and, as result, they "practically raised themselves". This distance, however, did not mean that she ignored their education completely. For Gilberto's mother, his studies were also a priority, and she encouraged him to pursue higher education.

In the first year of secondary school, Gilberto studied in a technical state school, where he found science subjects particularly difficult. He dropped out of school for a year to join the army, and he returned to school with little motivation, wanting to work "to help around the house": "Actually, I didn't really need it. My mother even told me "the priority is that you study, finish it'". He went back to studying because he was promised a promotion at his retail job if he finished his compulsory education.

In 2004, one year after he graduated from secondary school, at the age of 21, when the promise of promotion failed to materialize and he became disillusioned with retail, Gilberto, encouraged by his mother and his sister, who had just started on a Social Action scholarship at PUC-Rio in 2000, finally enrolled in the ProUni selection process. He believes that not having had to sit an entrance exam in order to obtain a scholarship from the Programme increased his chances of getting a place in higher education. He felt he was unprepared to sit an entrance exam for a public institution:

(...) I thought that what mattered was going through a door, like in a war, and then you had to find your way around in there. I thought it was much easier for me to get a place through the ProUni than through a UERJ or UFRJ [public universities] exam. ENEM was much easier back then, today it's beginning to look more like an entrance exam for public universities. I wasn't sure I could do that [entrance exam for public universities]. Because, the first times, I didn't go to a preparatory course. My sister tried to get me to go [to a preparatory course], but I didn't want to. I thought that what mattered was getting in, today I don't see it that way, I think you need to have the basics.

(...) I had no preparation, I thought I just had to go, heart and soul. I had five options [of institutions in the ProUni], among which I put down PUC-Rio, but it was high-level, for PUC you needed to get 7, 9. And I didn't get it. But I did get a place at a university near my house, UniLopes, for an Administration degree. I became really silly and happy: "My God, I made it!"

Upon receiving the news from his boss that his work hours could not be modified to accommodate his university studies, he became disappointed with the company's failure to recognise his dedication. He had, after all, completed secondary school with great difficulty because of the long work hours. He thus decided to quit and "invest in university life". In 2005, Gilberto began his Administration course at the UniLopes University Centre. His sister, however, insisted that he needed to get into PUC-Rio, which she considered to be a higher quality institution:

Actually, I didn't come because of her, but she would say: "you may even be at a good university, but PUC has this, it has that". So I started to hang out at PUC, at the PUC Fair, which happens every year, and I started to make up my own mind. It slowly got to me.

Although he considers that his time at UniLopes was vital for giving him access to the university world and for encouraging him to read more, specially about careers and human resources, Gilberto, perhaps under the influence by his sister, takes a critical view of the education he obtained at the College:

I liked it, but there were a few problems which I later saw were not OK. You get fooled, it's not the university's fault, but your own for being a part of it all. For example, there were terms there in which I didn't understand anything and the professor still gave me a pass. I basically handed in a blank test paper on matrixes. Today I know what matrixes are because I studied around it and paid my dues (...). So why would I want to get a diploma in Administration if I couldn't do a simple matrix? So, seeing all that, I decided not to fool myself.

Another decisive factor for Gilberto was the importance of studying in a prestigious institution that provided a diploma which was valued in the job market:

There was an interesting segment in Fantástico [a TV show], Jobs from A to Z, with Max Gehringer. I had already decided to come to PUC, but this programme helped me form my opinion. Because someone asked him: does the school, or the name of the school, count? He replied: "Do you want me to tell you something sad? It does. It's a label". This had a big impact on my decision.

While at the Administration college, Gilberto attended two years of preparatory courses and enrolled in two ProUni selection processes, in 2007 and 2008. In the latter year, he obtained a place at PUC-Rio, starting in the second period.

Danilo

In 2004, when still in secondary school, Danilo sat the entrance exam for History at a federal institution, a course he chose because of its lower candidate-to-place ratio. Since he failed to get in, he started working in telemarketing for a private higher education institution, through which he learned of the ProUni and enrolled in the Technical Course in Phonographic Production. Although he obtained a scholarship, Danilo questioned if his choice would guarantee him a job:

In my family, no one has higher education, and since I got in I felt like there was some pressure for me to follow a more traditional career. So as to have this security, to maybe be able to do what my parents never had the opportunity to do. Have a job that pays regular wages and gives me the security of a place in the job market.

Danilo decided to change his degree course, and he attended a preparatory course for four months. It was here that he learned that PUC-Rio offered Social Action and ProUni scholarships:

My[preparatory course] was a mess. So, in truth, I don't think it helped me with anything. What it did help me with was in allowing me to know that PUC-Rio existed, it was there, and that I could have a scholarship at PUC. I discovered the possibility of studying at PUC, but I ended up getting into [the University] Soares Freitas.

In this second attempt through the ProUni, he does not get into PUC-Rio, but he does get a scholarship for Social Sciences at another institution, a course he chose because of the Sociology classes he had at secondary school. It was only at his third attempt at the ProUni that he obtained a scholarship to PUC-Rio, also for Social Sciences, and, later, after a fourth selection process, he was able to start his Law degree at PUC-Rio. According to Danilo, he chose this course because it offered "the possibility of greater security after graduation".

Jussara

After graduating from secondary school and already with a job, it took a further two years for Jussara to sit her first entrance exam to the federal university system of Minas Gerais. She failed to get a place. She learned of the ProUni through friends, and sat the ENEM exam in 2007 hoping for the ProUni scholarship for 2008. She obtained the scholarship for a university in her town, in the interior of Minas Gerais. However, she had always wanted to leave the interior in order to increase her chances of upward mobility, and she thought that her best shot of achieving this was to study in a prestigious university. Her relation with professors and students attending universities provided her with a more detailed view of the quality of the different institutions. According to Jussara, "in the academic world, you can learn which are the good universities and which are the bad universities". She then decided to try for the ProUni, only putting down Catholic Universities as her options:

(...) I put down PUC-Minas, PUC-São Paulo, PUC-Rio. I tried various PUCs. None of the others called me, only this one [PUC-Rio] did. And I knew that any of these universities I chose - and I only chose good universities now that I tried - I knew that any of them that called me would be suitable. I knew it would be difficult to come, because it's always complicated when you leave everything behind to start a new life, but I came, and slowly but surely, I got here.

Due to her unsuccessful attempts at gaining a place in public universities, the student claims that without the ProUni she would never have made it into higher education. She says that she got the scholarship because she always enjoyed studying and she got into the habit of studying by herself for exams in the two years in which she worked. For her, ProUni offered the opportunity to chose a quality private institution:

[ProUni was] an opportunity, only those who have it really know this. You either get into a quality public university or you get into a good private one with a high-quality education. You generally go into a cheaper one, because you don't have the means to pay, but it usually leaves much to be desired as far as the quality of education goes. The ProUni allows this, it lets you chose the college you want, whether it's a bad one or a better one. I think it's a really good alternative for people who don't have money to pay.

Rafael

Rafael's first attempt to get into higher education was also through a public institution, the Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, one year after he completed secondary school. In order to prepare for the entrance exam, he moved cities to attend a preparatory course, which was unavailable in his hometown. After failing to gain a place at this institution, and since he had already sat the ENEM, he decided to enrol in the ProUni, so as to avoid delaying his university career any further and paying for more preparatory courses. In his first attempt, Rafael did not get a scholarship for his first choice, Film, but he did get a place for his last choice institution and course, Law at Faria Júnior University:

(...) my financial situation was at its limit. So I didn't want to spend a further year or semester in the preparatory course, I didn't want to, so I studied hard. (...) My sister had already warned me that Film was a very restrictive area, I didn't even see this, but it would be really difficult to make money. In Law I would have new perspectives. So I said: 'I'm going to Rio, see how this course is".

In Rio de Janeiro he met other students, with whom he shared a flat, and through one of them, a Law student at UERJ, he learned of the approval rates at the exam for the Brazilian Bar Association (Ordem dos Advogados do Brasil, OAB) for graduates from Rio de Janeiro universities. After two semesters, Rafael again entered the ProUni selection process and gained a scholarship for another university, better placed in the OAB exam than his original institution. In this new institution he had contact with professors who graduated from PUC-Rio, who spoke of the excellence of the course, which encouraged him to sit the ENEM exam one more time. Since he got a very good grade, he enrolled at the ProUni for PUC-Rio, obtaining the scholarship in 2008. He was able to gain equivalence for some of the disciplines he had studied at the other institutions.

Concluding Remarks

This article has shown how a sample of young students managed to obtain access to a prestige private university amidst a spectrum of private universities of varying quality. The social dispositions and conditions that characterized the sample under analysis were central for these students - once they had gathered informational capital and took advantage of the increased chances for access provided by the ProUni - to choose, and gain acceptance, to PUC-Rio.

In general, entry into higher education is considered improbable or even impossible. But the availability of a selection process that differs from the traditional entrance exams reintroduces this possibility into their horizons as a means to further their desire for upward mobility. The research also shows that the process of changing perceptions and entering higher education, and, more specifically, of gaining a place at PUC-Rio, is collective, since it is put into practice through the medium of family, schools, preparatory courses, teachers and colleagues at university.

I believe that the paths followed by Gilberto, Rafael, Jussara and Danilo express in an exemplary manner what Bourdieu called sens du jeu: the interiorization of the rules of the social game. If, initially, these individuals see higher education as a sort of "social leverage", they slowly come to perceive that different institutions and courses offer different opportunities. They thus chose to delay their degree in the hopes of increasing the value of their diploma, submitting themselves to many different ProUni selection processes so as to get into an institution that could offer them an advantage in the job market, in terms of institutional prestige, but also in what concerns the quality of the education more generally.

The careers of these students also allow us to assert that this perception of the importance of institutional quality - or, in other words, the acquisition of the 'sense of play' - depends, rather fundamentally, on the mediatory role of other social actors. By gathering informational capital, these scholars reorient their careers in order to ensure access to institutions of higher education that do not frustrate their hopes for social mobility. But since institutional quality cannot be guaranteed to all, we must question the degree to which the Programme truly universalizes not only access to higher education, but also the chance for an education that sustains hopes of expected upward mobility.

The author would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

- ALMEIDA, Wilson Mesquita de. 2009. USP para todos?: estudantes com desvantagens socioeconômicas e educacionais e fruição da universidade pública. São Paulo: Musa Editora.

- ______________. 2012. Ampliação do acesso ao ensino superior privado lucrativo brasileiro: um estudo sociológico com bolsistas do ProUni na cidade de São Paulo. Doctoral Thesis in Sociology, Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo (USP), São Paulo.

- BOURDIEU, Pierre. 1996. Razões práticas. São Paulo: Papirus Editora.

- BRASIL. Lei nº 11.096, de 13 de jan. de 2005. Institui o Programa Universidade para Todos - ProUni, regula a atuação de entidades beneficentes de assistência social no ensino superior altera a Lei nº 10.891, de 9 de julho de 2004, e dá outras providências. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www2.camara.gov.br/legin/fed/lei/2005/lei-11096-13-janeiro-2005-535381-norma-pl.html Acesso em: 10 de jun. de 2009.

» http://www2.camara.gov.br/legin/fed/lei/2005/lei-11096-13-janeiro-2005-535381-norma-pl.html - ___________. 2009. Tribunal de Contas da União. Relatório de auditoria operacional: Programa Universidade para Todos (ProUni) e Fundo de Financiamento ao Estudante do Ensino Superior (FIES). Relator Ministro José Jorge. Brasília: TCU. Disponível em:

» http://portal2.tcu.gov.br/portal/page/portal/TCU/comunidades/programas_governo/areas_atuacao/educacao/Relat%C3%B3rio%20de%20auditoria_Prouni.pdf - _________. 2013.Tribunal de Contas da União. Relatório de Monitoramento. Processo no TC 000.997/2013-7. Relator Ministro José Jorge. Brasília: TCU. Disponível em:http://portal2.tcu.gov.br/portal/page/portal/TCU/comunidades/programas_governo/areas_atuacao/educacao/Monitoramento%20Prouni.pdf Acesso em 10 de setembro de 2014.

» http://portal2.tcu.gov.br/portal/page/portal/TCU/comunidades/programas_governo/areas_atuacao/educacao/Monitoramento%20Prouni.pdf - COLEMAN, James S. 2000. "Social capital in the creation of human capital". In: P. Dascupta; I. Serageldin (orgs.), Social capital: a multifaceted perspective.Washington, D.C.: World Bank. pp. 19-39.

- ENADE. 2006. Relatório da IES (PUC-Rio). Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.inep.gov.br/enade Acesso em: 9 mai. 2010

» http://portal.inep.gov.br/enade - HASENBALG, Carlos; SILVA, Nelson do Valle. 1999. "Educação e diferenças raciais na mobilidade ocupacional no Brasil". In: Carlos Hasenbalg; Nelson do Valle Silva; Márcia Lima (orgs.), Cor e estratificação social. Rio de Janeiro: Contra Capa. pp. 217-230.

- HONORATO, Gabriela de Souza. 2005. Estratégias coletivas em torna da formação universitária:status, igualdade e mobilidade entre desfavorecidos. Mphil dissertation in Sociology, Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Sociais, IFCS, UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro.

- IBGE. 2014. Síntese de Indicadores Sociais: uma análise das condições de vida da população brasileira 2014. Rio de Janeiro. Disponivel em:Disponivel em: http://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/biblioteca-catalogo?view=detalhes&id=291985 Acesso em: 13 nov. 2015

» http://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/biblioteca-catalogo?view=detalhes&id=291985 - INEP/MEC. 2014. Censo da educação superior 2013. Brasília: INEP/MEC, 2014. Disponível em Disponível em http://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_superior/censo_superior/apresentacao/2014/coletiva_censo_superior_2013.pdf Acesso em: 13 nov. 2015

» http://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_superior/censo_superior/apresentacao/2014/coletiva_censo_superior_2013.pdf - MONGIM, Andrea Bayerl. 2010. Título universitário e prestígio social: percursos sociais de estudantes beneficiários do ProUni. Doctoral thesis in Anthropology, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói.

- PORTES, Écio Antônio. 2007. "O trabalho escolar das famílias populares". In: Maria Alice Nogueira; Geraldo Romanelli;Nadir Zago (orgs.), Família e escola: trajetórias de escolarização em camadas médias e populares. Petropólis:Vozes. pp.99-123.

- PROGRAMA cria 4 mil comissões locais para acompanhamento. 14 de maio de 2010. Portal MEC. Disponível em: Disponível em:http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=15429 Acesso em 28 de maio de 2013

» http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=15429 - RIBEIRO, Carlos Antonio Costa. 2010. "Expansão das escolas públicas e desigualdades de oportunidades educacionais no Brasil". 34º Encontro Anual da ANPOCS . Mimeo.

- SAMPAIO, Helena. 2000. O ensino superior no Brasil: o setor privado. São Paulo, Fapesp/Hucitec.

- SANTOS, Clarissa Tagliari. 2011. A chegada ao ensino superior: o caso dos bolsistas do ProUni da PUC-Rio. Mphil dissertation in sociology and anthropology, Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Sociais, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro.

- SOTERO, Edilza Correia. 2009. Negros no ensino superior: trajetória e expectativa de estudantes de Administração beneficiados por políticas de ação afirmativa (ProUni e Cotas) em Salvador. Mphil dissertation in sociology, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo.

- SOUZA E SILVA, Jailson de. 1999. "Por que uns e não outros?": caminhada de estudantes da Maré para a universidade. Doctoral thesis in Education, PUC-Rio, Rio de Janeiro.

- VARGAS, Hustana Maria. 2008. Represando e distribuindo distinção: a barragem do ensino superior.. Doctoral Thesis in Education, PUC-Rio. Rio de Janeiro.

- ZAGO, Nadir. 2000. "Quando os dados contrariam as previsões estatísticas: os casos de êxito escolar nas camadas socialmente desfavorecidas". Paidéia, 10(18): 70-80.

- ____________. 2007. "Prolongamento da escolarização nos meios populares e as novas formas de desigualdades educacionais". In: Lea Pinheiro Paixão; Nadir Zago (orgs.), Sociologia da educação: pesquisa e realidade brasileira. Petrópolis: Vozes. pp. 128-153.

-

1

The census term pardo is used to refer to people who define themselves as between white and black. We have used the term "mixed race" to refer to this idea, although, of course, it makes no real sense, since it assumes such an unimaginable category as "pure race".

-

2

"Pretos", "pardos", "brancos" and "indígenas" are the "ethnic" categories used by the national census.

-

3