Abstract:

This article aims to map the collective actions that discuss the right to early childhood education judged by the Courts of Justice of Brazil. The decisions analyzed were issued between October 2005 and July 2016, from all 27 Brazilian State courts. There were 289 collective actions along with 306 decisions related to the subject, with a higher concentration in the South and Southeast regions of the country. The Brazilian Public Prosecution Service was identified as the proponent in most of the lawsuits. In most cases, the right to early childhood education was recognized, ensuring access to both child care and preschool. Decisions related to budget issues and supply conditions were also identified.

Keywords:

Right to Education; Judicialization; Early Childhood Education

Resumo:

O presente artigo objetiva mapear as ações coletivas julgadas pelos Tribunais de Justiça do Brasil que discutem o direito à educação infantil. Analisaram-se as decisões dos 27 tribunais estaduais brasileiros, proferidas no período de outubro de 2005 a julho de 2016. Foram encontradas 289 ações coletivas e 306 decisões relacionadas à temática, havendo maior concentração nas regiões sudeste e sul do país. O Ministério Público foi identificado como o proponente na maioria das demandas. Na maioria dos casos o direito à educação infantil foi reconhecido, assegurando o acesso tanto à creche quanto à pré-escola, todavia também foram localizadas decisões relacionadas às questões orçamentárias e às condições de oferta.

Palavras-chave:

Direito à Educação; Judicialização; Educação Infantil

Introduction

The Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil of 1988 (CF/88) inaugurated a new phase in the Brazilian legal system. The 1988 Constitution enshrined a wide range of rights (Sadek, 2013SADEK, Maria Tereza. Judiciário e Arena Pública: um olhar a partir da ciência política. In: GRINOVER, Ada Peligrini; WATANABE, Kazuo. O Controle Jurisdicional de Políticas Públicas. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Forense, 2013. P. 1-32.), among which were social rights, foreseen as fundamental rights (Brasil, 1988BRASIL. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Nós, representantes do povo brasileiro, reunidos em Assembléia Nacional Constituinte para instituir um Estado Democrático, destinado a assegurar o exercício dos direitos sociais e individuais, a liberdade, a segurança, o bem-estar, o desenvolvimento, a igualdade e a justiça como valores supremos de uma sociedade fraterna, pluralista e sem preconceitos, fundada na harmonia social e comprometida, na ordem interna e internacional, com a solução pacífica das controvérsias, promulgamos, sob a proteção de Deus, a seguinte CONSTITUIÇÃO DA REPÚBLICA FEDERATIVA DO BRASIL. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 05 out. 1988.). It also enshrined as a fundamental right the principle of access to justice (Brasil, 1988BRASIL. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Nós, representantes do povo brasileiro, reunidos em Assembléia Nacional Constituinte para instituir um Estado Democrático, destinado a assegurar o exercício dos direitos sociais e individuais, a liberdade, a segurança, o bem-estar, o desenvolvimento, a igualdade e a justiça como valores supremos de uma sociedade fraterna, pluralista e sem preconceitos, fundada na harmonia social e comprometida, na ordem interna e internacional, com a solução pacífica das controvérsias, promulgamos, sob a proteção de Deus, a seguinte CONSTITUIÇÃO DA REPÚBLICA FEDERATIVA DO BRASIL. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 05 out. 1988., art. 5, XXXV), as well as mechanisms for its enforceability (Araújo, 2013ARAÚJO, Fernanda Raquel Thomaz de. Controle Judicial de Políticas Públicas e Realinhamento da Atividade Orçamentária na Efetivação do Direito à Educação: processo coletivo e a cognição do judiciário. 2013. 197 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Direito Negocial) - Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, 2013.), therefore authorizing the actioning of the Judiciary for the pursuit of such right.

The realization of social rights is generally achieved through the implementation of public policies (Duarte, 2004DUARTE, Clarice Seixas. Direito Público Subjetivo e Políticas Educacionais. São Paulo em Perspectiva, São Paulo, v. 18, n. 2, p. 113-118, 2004.; 2006DUARTE, Clarice Seixas. Reflexões sobre a Justiciabilidade do Direito à Educação no Brasil. In: HADDAD, Sérgio; GRACIANO, Mariângela. A Educação entre os Direitos Humanos. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2006. P. 127-153.; 2007DUARTE, Clarice Seixas. A Educação como um Direito Fundamental de Natureza Social. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 28, n. 100, p. 691-713, out. 2007.). Part of the doctrine already considers that the difference between the rights to freedom and the social rights has been overcome1 1 The rights to freedom (such as the right to property, the right to come and go, and the right to free speech, among others) would be those that depend on State abstention, i.e. on the non-interference of the State, for their guarantee. Social rights (which include the right to education, health, work, housing, food etc.) would be those that depend on either State’s prediction or on direct State action and intervention for their guarantee. In the words of Bobbio (1992, p. 21), “The former require purely negative obligations from others (including public bodies), and for those others to refrain from certain forms of behaviour, while the latter can be achieved only if a certain number of positive obligations are imposed on others (including public bodies)”. However, Stephen Holmes and Cass R. Sunstein (1999) argue that all rights are positive and demand some kind of public provision for their realization. For these authors, even the political rights and the protection of the rights of freedom depend both on the action of government agents and on public structure (for instance, the maintenance of Justice and public safety, which are maintained by the public purse). Both generate a complex of obligations of both negative and positive nature. ; this is based on the consideration that both dimensions depend on State’s both negative and positive provisions for their realization (Abramovich, 2005ABRAMOVICH, Víctor. Linhas de Trabalho em Direitos Econômicos, Sociais e Culturais: instrumentos e aliados. SUR - Revista Internacional de Direitos Humanos, São Paulo, v. 2, n. 2, p. 188-223, 2005.; Lage, 2013LAGE, Lívia Regina Savergnini Bissoli. Políticas Públicas como Programas e Ações para o Atingimento dos Objetivos Fundamentais do Estado. In: GRINOVER, Ada Pellegrini; WATANABE, Kazuo. O Controle Jurisdicional de Políticas Públicas. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 2013. P. 151-182.; Ximenes, 2014XIMENES, Salomão Barros. Direito à Qualidade na Educação Básica: teoria e crítica. São Paulo: QuartierLatin, 2014.). However, Abramovich (2005)ABRAMOVICH, Víctor. Linhas de Trabalho em Direitos Econômicos, Sociais e Culturais: instrumentos e aliados. SUR - Revista Internacional de Direitos Humanos, São Paulo, v. 2, n. 2, p. 188-223, 2005. clarifies that positive provisions are evident in relation to social rights. It is, therefore, through these provisions that social rights are enforced, i.e. through public policies.

Sousa Santos (2011)SOUSA SANTOS, Boaventura. Para uma Revolução Democrática da Justiça. 3. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. clarifies that a wide constitutionalizing of social rights without the support of public and social policies makes them difficult to achieve. Therefore, the space for their judicial demand is opened: the justice system replaces the “[...] public management system, which should have spontaneously carried out this social provision” (Sousa Santos, 2011SOUSA SANTOS, Boaventura. Para uma Revolução Democrática da Justiça. 3. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011., p. 26). Thus, it is necessary to understand the Judiciary as an actor that influences the implementation of public policies (Taylor, 2007TAYLOR, Matthew M. O Judiciário e as Políticas Públicas no Brasil. Dados Revista de Ciências Sociais, Rio de Janeiro, v. 50, n. 2, p. 229-257, 2007.), especially due to its actioning when the Public Power does not comply with its obligations (Cury; Ferreira, 2010CURY, Carlos Roberto Jamil; FERREIRA, Luiz Antonio Miguel. Justiciabilidade no Campo da Educação. Rbpae, Goiânia, v. 26, n. 1, p. 75-103, jan. 2010. Disponível em: <http://seer.ufrgs.br/rbpae/article/viewFile/19684/11467>. Acesso em: 02 jan. 2016.

http://seer.ufrgs.br/rbpae/article/viewF...

).

Consequently, “[...] the figures regarding the entry of cases into the Judiciary System indicate a growing and continuous increase in the number of actions” (Sadek, 2013SADEK, Maria Tereza. Judiciário e Arena Pública: um olhar a partir da ciência política. In: GRINOVER, Ada Peligrini; WATANABE, Kazuo. O Controle Jurisdicional de Políticas Públicas. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Forense, 2013. P. 1-32., p. 17). Therefore, there has been more access to the Judiciary System as a means of guaranteeing the rights foreseen in the CF/88 and in the Brazilian legal order. Sousa Santos (2011)SOUSA SANTOS, Boaventura. Para uma Revolução Democrática da Justiça. 3. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. clarifies that “[...] the redemocratization and the new constitutional milestone have given greater credibility to the use of judicial means as an alternative to achieve rights” (Sousa Santos, 2011SOUSA SANTOS, Boaventura. Para uma Revolução Democrática da Justiça. 3. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011., p. 25), which is not only due to the legal and political culture of the country, but also because of the precariousness of economic and social rights (Sousa Santos, 2011SOUSA SANTOS, Boaventura. Para uma Revolução Democrática da Justiça. 3. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011.; Silveira, 2013SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. Conflitos e Consensos na Exigibilidade Judicial do Direito à Educação Básica. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 34, n. 123, p. 371-387, abr./jun. 2013. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-73302013000200003>. Acesso em: 09 jan. 2016.

http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=s...

).

The right to education is among the social rights that have been brought to the Judiciary. Such right is envisaged as a fundamental social right by the CF/88, in its article 6 (Brasil, 1988BRASIL. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Nós, representantes do povo brasileiro, reunidos em Assembléia Nacional Constituinte para instituir um Estado Democrático, destinado a assegurar o exercício dos direitos sociais e individuais, a liberdade, a segurança, o bem-estar, o desenvolvimento, a igualdade e a justiça como valores supremos de uma sociedade fraterna, pluralista e sem preconceitos, fundada na harmonia social e comprometida, na ordem interna e internacional, com a solução pacífica das controvérsias, promulgamos, sob a proteção de Deus, a seguinte CONSTITUIÇÃO DA REPÚBLICA FEDERATIVA DO BRASIL. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 05 out. 1988.), endowed with full justiciability, which is conceptualized as the possibility of being enforced through the justice system (Pannunzio, 2009PANNUNZIO, Eduardo. O Poder Judiciário e o Direito à Educação. In: RANIERI, Nina Beatriz Stocco. Direito à Educação: aspectos constitucionais. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 2009. P. 61-88.; Silveira; 2013SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. Conflitos e Consensos na Exigibilidade Judicial do Direito à Educação Básica. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 34, n. 123, p. 371-387, abr./jun. 2013. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-73302013000200003>. Acesso em: 09 jan. 2016.

http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=s...

; Ximenes; Grinkraut, 2014XIMENES, Salomão; GRINKRAUT, Ananda. Acesso à Educação Infantil no novo PNE: parâmetros de planejamento, efetivação e exigibilidade do direito. Cadernos CENPEC, São Paulo, v. 4, n. 1, p. 78-101, jun. 2014.; Scaff; Pinto, 2016SCAFF, Elisângela Alves da Silva; PINTO, Isabela Rahal de Rezende. O Supremo Tribunal Federal e a Garantia do Direito à Educação. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 21, n. 65, p. 431-454, jun. 2016.). Muñoz (2006)MUÑOZ, Vernor. Do Direito à Justiça. In: HADDAD, Sérgio; GRACIANO, Mariângela. A Educação entre os Direitos Humanos. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2006. P. 43-60. and Graciano, Marinho and Fernandes (2006)GRACIANO, Mariângela; MARINHO, Carolina; FERNANDES, Fernanda. As Demandas Judiciais por Educação na Cidade de São Paulo. In: HADDAD, Sérgio; GRACIANO, Mariângela. A Educação entre os Direitos Humanos. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2006. P. 156-196. indicate the actioning of the justice system as a means for the realization of the right to education. Thus, in the last few years, demands requiring the enforcement of this right before the Judiciary have gained prominence (Scaff; Pinto, 2016SCAFF, Elisângela Alves da Silva; PINTO, Isabela Rahal de Rezende. O Supremo Tribunal Federal e a Garantia do Direito à Educação. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 21, n. 65, p. 431-454, jun. 2016.).

Demands involving the right to education have increasingly been brought to the attention of the Brazilian courts, especially because of the social inequalities regarding the access to this right in the country (Silveira, 2013SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. Conflitos e Consensos na Exigibilidade Judicial do Direito à Educação Básica. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 34, n. 123, p. 371-387, abr./jun. 2013. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-73302013000200003>. Acesso em: 09 jan. 2016.

http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=s...

). “The growth of judicial enforceability regarding the right to education may be related to the low effectiveness of the declared rights and to the existence of legal remedies and institutions of the Justice System that facilitate such auctioning” (Silveira, 2010SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. O Direito à Educação de Crianças e Adolescentes: análise da atuação do Tribunal de Justiça de São Paulo (1991-2008). 2010. 303 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2010., p. 3). The Judiciary has been called to judge cases related to the subject (Cury; Ferreira, 2010CURY, Carlos Roberto Jamil; FERREIRA, Luiz Antonio Miguel. Justiciabilidade no Campo da Educação. Rbpae, Goiânia, v. 26, n. 1, p. 75-103, jan. 2010. Disponível em: <http://seer.ufrgs.br/rbpae/article/viewFile/19684/11467>. Acesso em: 02 jan. 2016.

http://seer.ufrgs.br/rbpae/article/viewF...

, Scaff; Pinto, 2016SCAFF, Elisângela Alves da Silva; PINTO, Isabela Rahal de Rezende. O Supremo Tribunal Federal e a Garantia do Direito à Educação. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 21, n. 65, p. 431-454, jun. 2016.). Interferences from the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF) in educational demands (Ranieri, 2009RANIERI, Nina Beatriz Stocco. Os Estados e o Direito à Educação na Constituição de 1988: comentários acerca da jurisprudência do Supremo Tribunal Federal. In: RANIERI, Nina Beatriz Stocco. Direito à Educação: aspectos constitucionais. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 2009. P. 39-59.; Scaff; Pinto, 2016SCAFF, Elisângela Alves da Silva; PINTO, Isabela Rahal de Rezende. O Supremo Tribunal Federal e a Garantia do Direito à Educação. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 21, n. 65, p. 431-454, jun. 2016.) have also occurred. This interference ends up generating the phenomenon of judicialization, which is when discussions or decisions related to public policies are brought to the Judiciary instead of the Executive and Legislative Powers (Tate; Vallinder, 1995TATE, C. Neal; VALLINDER, Torbjörn. The Global Expansion of Judicial Power: the judicialization of politics. In: TATE, C. Neal; VALLINDER, Torbjörn. The Global Expansion of Judicial Power. New York: New York Unversity Press, 1995. P. 1-10.; Barroso, 2009BARROSO, Luís Roberto. Judicialização, ativismo e legitimidade democrática. Revista Eletrônica de Direito do Estado, Salvador, n. 18, abr./jun. 2009. Disponível em: <http://www.oab.org.br/editora/revista/users/revista/1235066670174218181901.pdf>. Acesso em: 19 jan. 2016.

http://www.oab.org.br/editora/revista/us...

; Silveira, 2013SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. Conflitos e Consensos na Exigibilidade Judicial do Direito à Educação Básica. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 34, n. 123, p. 371-387, abr./jun. 2013. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-73302013000200003>. Acesso em: 09 jan. 2016.

http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=s...

). This phenomenon has been gaining relevance in current research (Silveira, 2008SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. A Exigibilidade do Direito à Educação Básica pelo Sistema de Justiça: uma análise da produção brasileira do conhecimento. RBPAE, Porto Alegre, v. 24, n. 3, p. 537-555, dez. 2008.).

In this area, demands regarding early childhood education have grown among legal disputes related to education (Silveira, 2008SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. A Exigibilidade do Direito à Educação Básica pelo Sistema de Justiça: uma análise da produção brasileira do conhecimento. RBPAE, Porto Alegre, v. 24, n. 3, p. 537-555, dez. 2008.). Enshrined as a right of workers and children in the CF/88 (Brasil, 1988BRASIL. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Nós, representantes do povo brasileiro, reunidos em Assembléia Nacional Constituinte para instituir um Estado Democrático, destinado a assegurar o exercício dos direitos sociais e individuais, a liberdade, a segurança, o bem-estar, o desenvolvimento, a igualdade e a justiça como valores supremos de uma sociedade fraterna, pluralista e sem preconceitos, fundada na harmonia social e comprometida, na ordem interna e internacional, com a solução pacífica das controvérsias, promulgamos, sob a proteção de Deus, a seguinte CONSTITUIÇÃO DA REPÚBLICA FEDERATIVA DO BRASIL. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 05 out. 1988., articles 7, XXV and 208, IV), this stage is currently considered the first one of K-12 Education, designed for services in child care centers (for children between zero and three years of age) and in pre-schools (for children of four and five years of age2

2

After the issue of constitutional amendments (EC) n. 53/2006 (Brasil, 2006a) and 59/2009 (Brasil, 2009a), as well as Law n. 11274/2006 (Brasil, 2006b), since it was originally intended for the care of children between zero and six years of age.

(Brasil, 1996BRASIL. Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 23 dez. 1996.), with pre-school being considered compulsory (Brasil, 2009aBRASIL. Emenda Constitucional nº 59, de 11 de novembro de 2009. Acrescenta § 3º ao art. 76 do Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias para reduzir, anualmente, a partir do exercício de 2009, o percentual da Desvinculação das Receitas da União incidente sobre os recursos destinados à manutenção e desenvolvimento do ensino de que trata o art. 212 da Constituição Federal, dá nova redação aos incisos I e VII do art. 208, de forma a prever a obrigatoriedade do ensino de quatro a dezessete anos e ampliar a abrangência dos programas suplementares para todas as etapas da educação básica, e dá nova redação ao § 4º do art. 211 e ao § 3º do art. 212 e ao caput do art. 214, com a inserção neste dispositivo de inciso VI.. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 12 nov. 2009a. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/emendas/emc/emc59.htm>. Acesso em: 19 jan. 2016.

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/con...

). Although the CF/88 had already enshrined it as a right, the manifestation of the Judiciary confirmed that it is indeed a duty of the State. This occurred upon the trial of Extraordinary Appeal n. 436996, in 2005, by STF (Brasil, 2005BRASIL. Supremo Tribunal Federal. Recurso Extraordinário nº 436996. Recorrente: Ministério Público do Estado de São Paulo. Recorrido: Município de Santo André. Relator: Ministro Celso de Mello. Julgamento: 26 de outubro de 2005. Diário de Justiça da União, Brasília, 07 nov. 2005.). This decision drove the Public Power to acknowledge its duty to offer children education according to the demand3

3

That decision was rendered prior to the issue of EC n. 59/2009 (Brasil, 2009a), which made education from the age of 4 to 17 compulsory. This results in the necessary universalization of pre-school, since this stage of education is intended to serve children of 4 and 5 years of age, under the terms of art. 30, II, of the National Educational Bases and Guidelines Law (LDB) (Brasil, 1996).

, a fact which has been recognized by researchers (Silveira, 2014SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. Exigibilidade do Direito à educação infantil: uma análise da jurisprudência. In: SILVEIRA, Adriana Dragone; GOUVEIA, Andréa Barbosa; SOUZA, Ângelo Ricardo de. Conversas sobre Políticas Educacionais. Curitiba: Appris, 2014. P. 167-188.). After this process, a favorable constitutional interpretation by the STF on the topic (Ximenes; Grinkraut, 2014XIMENES, Salomão; GRINKRAUT, Ananda. Acesso à Educação Infantil no novo PNE: parâmetros de planejamento, efetivação e exigibilidade do direito. Cadernos CENPEC, São Paulo, v. 4, n. 1, p. 78-101, jun. 2014.) was consolidated.

The recurrence of trials related to demands of early childhood education has been relevant, as indicated by Graciano, Marinho and Fernandes (2006)GRACIANO, Mariângela; MARINHO, Carolina; FERNANDES, Fernanda. As Demandas Judiciais por Educação na Cidade de São Paulo. In: HADDAD, Sérgio; GRACIANO, Mariângela. A Educação entre os Direitos Humanos. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2006. P. 156-196., Silveira (2010)SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. O Direito à Educação de Crianças e Adolescentes: análise da atuação do Tribunal de Justiça de São Paulo (1991-2008). 2010. 303 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2010., Silveira (2015)SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. Possibilidades e Limites da Judicialização da Educação: análise do sistema de justiça do Paraná. Curitiba: UFPR, 2015. and Scaff and Pinto (2016)SCAFF, Elisângela Alves da Silva; PINTO, Isabela Rahal de Rezende. O Supremo Tribunal Federal e a Garantia do Direito à Educação. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 21, n. 65, p. 431-454, jun. 2016. research. Silveira (2010)SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. O Direito à Educação de Crianças e Adolescentes: análise da atuação do Tribunal de Justiça de São Paulo (1991-2008). 2010. 303 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2010. clarifies that the increase in litigation regarding this stage of education is related to its envisioning as a right in educational legislation and, more recently, its inclusion in the Fund for Maintenance and Development of Basic Education and Valuing of Education Professionals (FUNDEB). This fund, established through EC n. 53/2006 (Brasil, 2006aBRASIL. Emenda Constitucional nº 53, de 19 de dezembro de 2006. Dá nova redação aos arts. 7º, 23, 30, 206, 208, 211 e 212 da Constituição Federal e ao art. 60 do Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 20 dez. 2006a. P. 5. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Constituicao/Emendas/Emc/emc53.htm>. Acesso em: 19 jan. 2016.

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Con...

), creates an expectation of increasing resources to meet its growing demand.

Among the demands that have been brought to the knowledge of the Judiciary are actions aimed at the realization of the right to early childhood education, especially ones requiring access. As stated in the works of Silveira (2010SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. O Direito à Educação de Crianças e Adolescentes: análise da atuação do Tribunal de Justiça de São Paulo (1991-2008). 2010. 303 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2010.; 2014SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. Exigibilidade do Direito à educação infantil: uma análise da jurisprudência. In: SILVEIRA, Adriana Dragone; GOUVEIA, Andréa Barbosa; SOUZA, Ângelo Ricardo de. Conversas sobre Políticas Educacionais. Curitiba: Appris, 2014. P. 167-188.; 2015)SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. Possibilidades e Limites da Judicialização da Educação: análise do sistema de justiça do Paraná. Curitiba: UFPR, 2015., Corrêa (2014)CORRÊA, Luiza Andrade. A Judicialização da Política Pública de Educação Infantil no Tribunal de Justiça de São Paulo. 2014. 236 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Direito) - Pós-Graduação em Direito, Faculdade de Direito, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2014., Graciano, Marinho and Fernandes (2006)GRACIANO, Mariângela; MARINHO, Carolina; FERNANDES, Fernanda. As Demandas Judiciais por Educação na Cidade de São Paulo. In: HADDAD, Sérgio; GRACIANO, Mariângela. A Educação entre os Direitos Humanos. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2006. P. 156-196., the right to early childhood education has been demanded before the Judiciary through various means, both individual and collective. In individual actions, the interested party demands the fulfillment of its individual right. In the case of early childhood education, this is usually done through the demand of the child, who is represented by his/her parents, to obtain a vacancy that was not granted in the administrative sphere, through an action aimed to fulfill its subjective right. Another form of actioning that has grown in recent years is through collective measures of enforceability of the right to early childhood education, which aims to protect the right of a collectivity of children.

The right to education as a social right would find in collective actions a more appropriate means to demand (Silveira, 2013SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. Conflitos e Consensos na Exigibilidade Judicial do Direito à Educação Básica. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 34, n. 123, p. 371-387, abr./jun. 2013. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-73302013000200003>. Acesso em: 09 jan. 2016.

http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=s...

; Leal, 2014LEAL, Márcio Flávio Mafra. Ações Coletivas. São Paulo: Editora Revista dos Tribunais, 2014.). This is because social rights have the characteristic of being collective rights (Zaneti Junior, 2013ZANETI JUNIOR, Hermes. A Teoria da Separação de Poderes e o Estado Democrático Constitucional: funções de governo e funções de garantia. In: GRINOVER, Ada Pellegrini; WATANABE, Kazuo. O Controle Jurisdicional de Políticas Públicas. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 2013. P. 33-72.), since their ownership is not of a single individual, but of the society (Araújo, 2013ARAÚJO, Fernanda Raquel Thomaz de. Controle Judicial de Políticas Públicas e Realinhamento da Atividade Orçamentária na Efetivação do Direito à Educação: processo coletivo e a cognição do judiciário. 2013. 197 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Direito Negocial) - Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, 2013.). In this way, there is the understanding that their best care would be given collectively (through the implementation of public policies, for instance), which would prevent the prioritization of a single individual in detriment of others (Araújo, 2013ARAÚJO, Fernanda Raquel Thomaz de. Controle Judicial de Políticas Públicas e Realinhamento da Atividade Orçamentária na Efetivação do Direito à Educação: processo coletivo e a cognição do judiciário. 2013. 197 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Direito Negocial) - Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, 2013.; Jacob, 2013JACOB, Cesar Augusto Alckmin. A “Reserva do Possível”: obrigação de previsão orçamentária e de aplicação da verba. In: GRINOVER, Ada Pellegrini; WATANABE, Kazuo. O Controle Jurisdicional de Políticas Públicas. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 2013. P. 237-283.). Thus, the privilege of a few while others remain without state protection would be avoided (Lopes, 2002LOPES, José Reinaldo de Lima. Direito Subjetivo e Direitos Sociais: o dilema do judiciário no estado social de direito. In: FARIA, José Eduardo (Org.). Direitos Humanos, Direitos Sociais e Justiça. São Paulo: Malheiros Editores, 2002.). It is not denied that these rights can be demanded individually, but that their fulfillment through collective means composes an important dimension of them.

Thus, it seems relevant to assess the extent to which the Brazilian Courts of Justice are being called upon to decide on the right to early childhood education through collective measures, in order to ascertain whether this right has been requested by its own way. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to map the collective actions that demand the right to early childhood education before the Courts of Justice of Brazil from October 2005 to July 20164 4 The present study integrates the research project Efeitos da atuação do sistema de justiça no direito à educação infantil: um estudo da judicialização da política educacional em três estados brasileiros, funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). .

Methodological Procedures

This research was restricted to the Courts of Justice of Brazil due to the legal norms that define that demands involving municipalities are under State jurisdiction (Brasil, 1988BRASIL. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Nós, representantes do povo brasileiro, reunidos em Assembléia Nacional Constituinte para instituir um Estado Democrático, destinado a assegurar o exercício dos direitos sociais e individuais, a liberdade, a segurança, o bem-estar, o desenvolvimento, a igualdade e a justiça como valores supremos de uma sociedade fraterna, pluralista e sem preconceitos, fundada na harmonia social e comprometida, na ordem interna e internacional, com a solução pacífica das controvérsias, promulgamos, sob a proteção de Deus, a seguinte CONSTITUIÇÃO DA REPÚBLICA FEDERATIVA DO BRASIL. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 05 out. 1988.). Since municipalities are the competent bodies for offering early childhood education (art. 30, VI of the CF/88 and 11, V of the National Educational Bases and Guidelines Law (LDB)), it is understood that most of the demands that discuss the offering of the right to early childhood education will be judged, in the first instance, by state judges; the decisions of second instance, in turn, will be submitted to the Courts of Justice of the States.

Furthermore, the choice of analyzing only the decisions issued by the second instance - issued by the Courts of Justice - is due to the fact that the decisions issued against the municipalities are subject to a necessary review (Brasil, 1973BRASIL. Lei nº 5.869, de 11 de janeiro de 1973. Institui o Código de Processo Civil. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 17 jan. 1973.; 2015BRASIL. Lei nº 13.105, de 16 de março de 2015. Código de Processo Civil. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 17 mar. 2015. P. 1. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2015/lei/l13105.htm>. Acesso em: 19 jan. 2016.

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_at...

). This means that sentences issued against the municipalities in the first instance must be referred to the Courts of Justice, regardless of whether or not the municipality has filed a voluntary appeal. Therefore, decisions at first instance could change, which is the reason why we decided to analyze decisions at court of appeal. Thus, the research that bases the analysis of this article does not present all the collective demands that were brought to the attention of the Judiciary, but only the demands that were judged by the Brazilian Courts of Justice during the period.

Decisions issued in the period between October 2005 and July 2016 were selected. The period was chosen considering the date in which the STF issued its decision that recognized early childhood education as a duty of the Government. Since it is a period of approximately one decade (from 2005 to 2016), it may serve as a portrait of the collective demand of the right to early childhood education in Brazil.

To collect the decisions, a search was conducted through the search tool for jurisprudence on the websites of all 27 Brazilian Courts of Justice, using the keywords: child care, preschool, and early childhood education. In order to select the decisions, we opted to read each program5 5 The program is a summary of the decision and must contain clearly and concisely its object and content. , selecting those that indicated that the decision had been issued in a collective action and discussing the right to early childhood education. The selected decisions were separated for further reading and categorization, and both rulings6 6 The ruling is the collegiate decision issued by the courts (Brasil, 2015). In these cases, the judgment is performed by three court of appeal judges, who vote for the maintenance or modification of the decision at first instance and issue the ruling. and monocratic decision makings7 7 In some cases, the court of appeal judge is allowed to issue a decision in a monocratic way, i.e., it does not pass through collegiate judgment. Therefore, the decision is issued by a single court of appeal judge. were selected.

From the results obtained by this research method, those that were issued in individual actions were excluded, as well as those that referred exclusively to uninterrupted service in vacations and school recesses, adaptation of building accessibility to people with disabilities, direct actions of unconstitutionality questioning municipal laws, decisions issued in compliance with the sentence, or executions of conduct adjustment terms8 8 The conduct adjustment term is an extrajudicial instrument for conflict resolution used by the Brazilian Public Prosecution Service and negotiated between the entity and the public administration, aiming at the protection of the collective rights. . Moreover, decisions in collective actions that aimed at the protection of exclusively individual interests, or of a small number of children, were not selected, since according to Leal (2014)LEAL, Márcio Flávio Mafra. Ações Coletivas. São Paulo: Editora Revista dos Tribunais, 2014., the number of holders should also be considered for the characterization of a collective right.

However, it is worth clarifying that the option to collect decisions through the jurisprudence search tool is a limiting factor, since some courts do not provide, for instance, decisions issued in cases that had been kept under legal confidentiality. Thus, the result of the present research refers to the information that has been provided by the courts through these tools. It is not possible to claim that these data represent the totality of decisions issued by the Brazilian Courts regarding the subject9 9 Regarding the Brazilian Courts of Justice of the Federal District and Territories, Mato Grosso do Sul and Espírito Santo, there were technical problems in the jurisprudential search tool that prevented access to all the results obtained through the search with the indicated descriptors. Thus, only the first 500, 400 and 12 results respectively were accessible, even though the tool was accessed at different periods between the second half of 2016 and the first quarter of 2017. .

After searching all Brazilian Courts of Justice, and considering the indicated criteria, 495 decisions were selected for reading and analysis. Within these decisions, the access to the whole information of 24 decisions was not possible, as they were kept in legal confidentiality; thus, they were excluded from the analysis. The remainder were read out, and another 164 decisions were excluded by the same criteria described above, which had not been identified by reading only the program. Therefore, 306 decisions composed the analyzes that will be further demonstrated.

Afterwards, a complete reading was performed aiming to identify the number of procedures by each Federation state; the instruments used to file the demand and the appeals brought to the attention of the courts; whether or not there was more than one appeal related to the same originating action at first instance; the distribution of decisions made over time; the plaintiffs; whether the right to early childhood education was recognized in each case or not; the classification of the demand according to the substage to which it was linked10 10 It is worth noting that, notwithstanding LDB’s clarification that child care is given to children up to three years-old and preschool to four and five-year-old children (Brasil, 1996), many misunderstandings in the use of these nomenclatures by court decisions are still perceivable. Therefore, the classification of demands according to the substages was based on the age group indicated in the decisions and based on the LDB, even though the decisions adopted different nomenclature. In cases in which the decision referred only to the substages and did not indicate the age group considered, the classification of the demand was done according to the nomenclature indicated in the decision. ; and other relevant access-related specifications, such as budget issues or offer conditions discussed in these decisions.

Mapping of the Collective Actions in which the Right to Early Childhood Education is Demanded in the Brazilian Courts of Justice

According to the adopted methodology, 306 decisions were found in collective actions, in 22 states of all five regions of the country. The region with the largest number of decisions is the Southeast region, followed by the Southern, Central-West, Northeast, and Northern regions. Table 1 indicates the number of judicial decisions found in each court, classifying them according to the appeal instrument used:

Judicial Decisions in Brazilian Courts of Justice on Collective Actions that Examine Early Childhood Education (2005-2016)

Following the analysis of the decisions, it was also verified that some of them were issued in relation to the same process originated at first instance. Therefore, the number of 306 located decisions does not indicate that all decisions are collective actions that had been brought in the courts.

There are cases in which, through the jurisprudential search, the decision of the interlocutory appeal filed against the preliminary injunction was identified, as well as the decision of the judicial review or appeal, for instance. This finding was possible by analyzing the content of the decisions or by means of the consulting tool of the process at court of appeals in the websites of the courts, when the number of the originating action of first instance was present. Thus, if the content of the decisions and the requested municipality were similar in several decisions, the procedural consultation was carried out in order to compare the number of the originating action. This procedure allowed us to identify the cases in which several decisions were coming from the same action at first instance.

Thus, Table 2 was developed. It indicates the number of actions found in each court, classified according to the procedural instrument used: writ of mandamus15 15 The writ of mandamus is an action proposed to protect the clear legal right of its holder, under the terms of the art. 5, LXIX, from the CF/88, and may be filed collectively pursuant to the art. 5, LXX, from the same legal document (Brasil, 1988). , public civil action16 16 The public civil action is a procedural instrument provided for the protection of diffuse and collective interests, under the terms of the art. 129, III, from CF/88 (Brasil, 1988), which, among other matters, examines the rights of children and adolescents, under the terms of the art. 201, V, from the Brazilian Child and Adolescent Statute (ECA) (Brasil, 1990). or other actions. All 306 decisions issued originate from 289 collective demands that were processed at first instance, identifying different decisions in relation to the same collective action originated in the states of Sergipe, Minas Gerais, São Paulo, Rio Grande do Sul, and Santa Catarina. In other states, no more than one decision related to the same originating process was identified. From Table 2, it is also possible to infer that 95.5% of the collective actions are public civil actions, which demonstrates the absolute preponderance of this instrument as a form of collective demand for the right to early childhood education.

Collective Actions Brought to the Attention of the Brazilian Courts of Justice, Whose Decisions Examine Early Childhood Education (2005-2016)

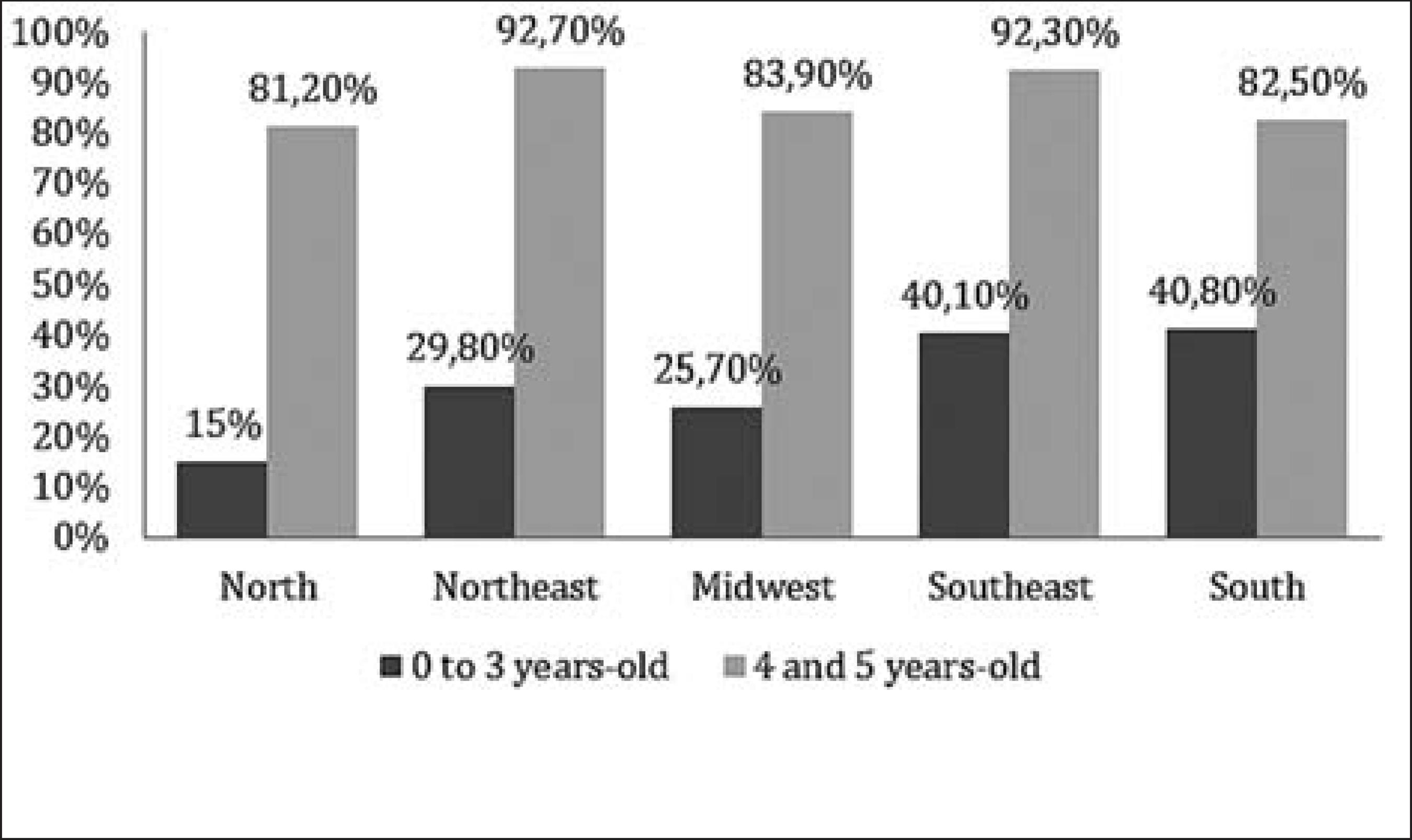

It is worth noting the small number of cases found in the Brazilian Courts of the Northern and Northeast regions when compared to the other regions. This information raises the question of why the process of legal demand for the right to early childhood education is considerably lower in these regions. According to the literature on the subject, the low effectiveness of the law system would generate a greater legal demand for its guarantee (Sousa Santos, 2011SOUSA SANTOS, Boaventura. Para uma Revolução Democrática da Justiça. 3. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011.). Therefore, there would be a larger amount of actions in the locations where the guarantee of the right is smaller. However, in accordance with the data of the Report of the 1st Cycle of Monitoring Goals of the Brazilian National Plan for Education (PNE), it is evident that the demands are not concentrated in the locations with lower rates of school attendance, for the population of zero to five years-old, as shown in charts 1 and 2:

Percentage of the Population from Zero to Three Years- Old and of Four- and Five-Years-Old Who Attended Child Care Centers and Preschools in 2014 by Region

Percentage of the Population from Zero to Three Years- Old and of Four and Five Years-Old Who Attended Child Care Centers and Preschools in 2014 by State

According to Chart 1, the region of the country with the lowest percentage of children attending early childhood education is the Northern region, which is precisely the one with the lowest number of demands regarding the topic. However, the Southeast region, which has the highest number of demands for the right to early childhood education, is the second region with the highest percentage children attending child care and preschool.

When we turn our attention to the population who attends early childhood education by state (Chart 2), there are cases in which states present a high percentage of attendance and either a low number of demands that request the right to early childhood education or none (as in the case of the state of Ceará in relation to the four- and five-year-old age group). Nonetheless, there are also cases in which there is low attendance in states that present low legal demand of this right (as in the case of the states of Amapá, Amazonas, and Acre).

Moreover, there are cases in which the demand occurs in states with higher attendance rates, as in the case of the states of São Paulo and Santa Catarina, for instance. There are also cases of states that present more demands, but a lower attendance rate, as in the case of the state of Rio Grande do Sul.

These data allow us to indicate that the occurrence of the judicialization of the policies on early childhood education cannot be explained exclusively by the ineffectiveness of the educational policy. It is necessary to carry out other studies that seek to identify the causes of the judicialization of the policies on early childhood education and why it occurs unevenly in the Brazilian states, specifically given the inequality of the provided care.

Rosemberg (2015a)ROSEMBERG, Fulvia. A Complexidade do Multiculturalismo no Brasil: relações de gênero, família e políticas de educação infantil. In: ARTES, Amélia; UNBEHAUM, Sandra. Escritos de Fúlvia Rosemberg. São Paulo: Cortez, 2015a. P. 189-200. indicates how the emphasis has been placed on the coverage of early childhood education, especially for children from zero to three year of age, through family-centered and domestic policies. The author also indicates that small children have their visibility associated with the private sphere, especially in the domestic space under the care of their parents. This vision of care as a family matter could generate a low demand for the search of rights of the children by the families themselves. This discussion could prove another hypothesis, which is pointed out by Sousa Santos (2011)SOUSA SANTOS, Boaventura. Para uma Revolução Democrática da Justiça. 3. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011., related to the increase in the search of the Judiciary by the population in order to guarantee their social rights, according to a greater awareness of their rights. If the family does consider the care of the child to be held in the domestic space and as something that belongs to the private sphere, they hardly know that it is the right of the child and that it may be demanded from the public authorities.

In this sense, studies that evaluate whether the demand for early childhood education is related to the awareness of the population of education as a social right are also needed. Once people know of these rights, the demand from the judicial system when the law is violated could be higher.

This is an important discussion in the policies of the early childhood education field, since access to early childhood education is unequal “[...] according to socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, regional, and home location variables” (Rosemberg, 2015bROSEMBERG, Fúlvia. Análise das Discrepâncias entre as Conceituações de Educação Infantil do Inep e do IBGE: sugestões e subsídios para uma maior e mais eficiente divulgação dos dados. In: ARTES, Amélia; UNBEHAUM, Sandra. Escritos de Fúlvia Rosemberg. São Paulo: Cortez, 2015b. P. 241-277., p. 259). Thus, the right is doubly violated: the child does not have access to early childhood education, nor access to justice to demand it.

Another factor taken into consideration to evaluate the judicial demand of early childhood education was the amount of these demands over time. The decisions analyzed in this study comprised the period between 2006 and 2016, as shown in Chart 3. The number of decisions made by the Brazilian Courts of Justice had been growing annually, having reached its peak in 2015. Yet, it is important to emphasize that the decisions from 2016 were analyzed up to July. This number shows that the right to early childhood education has been increasing in demand through collective measures in Brazil during the last ten years, especially after the Constitutional Amendment 59/2009 (Brasil, 2009aBRASIL. Emenda Constitucional nº 59, de 11 de novembro de 2009. Acrescenta § 3º ao art. 76 do Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias para reduzir, anualmente, a partir do exercício de 2009, o percentual da Desvinculação das Receitas da União incidente sobre os recursos destinados à manutenção e desenvolvimento do ensino de que trata o art. 212 da Constituição Federal, dá nova redação aos incisos I e VII do art. 208, de forma a prever a obrigatoriedade do ensino de quatro a dezessete anos e ampliar a abrangência dos programas suplementares para todas as etapas da educação básica, e dá nova redação ao § 4º do art. 211 e ao § 3º do art. 212 e ao caput do art. 214, com a inserção neste dispositivo de inciso VI.. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 12 nov. 2009a. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/emendas/emc/emc59.htm>. Acesso em: 19 jan. 2016.

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/con...

) - which establishes 2016 as the deadline for the progressive implementation of universal access to preschool. This information enables us to speculate that the inclusion of the four and five years-old in the age range of compulsory education generated a greater movement towards the guarantee of this right by the justice system. Although the right to education already existed and was configured as a duty of the State, the determination of compulsory education for this age group seems to have raised more concern for its implementation.

Number of Decisions Made Over Time by the Brazilian Courts of Justice in Collective Actions that Demanded the Right to Early Childhood Education (2006-2016)

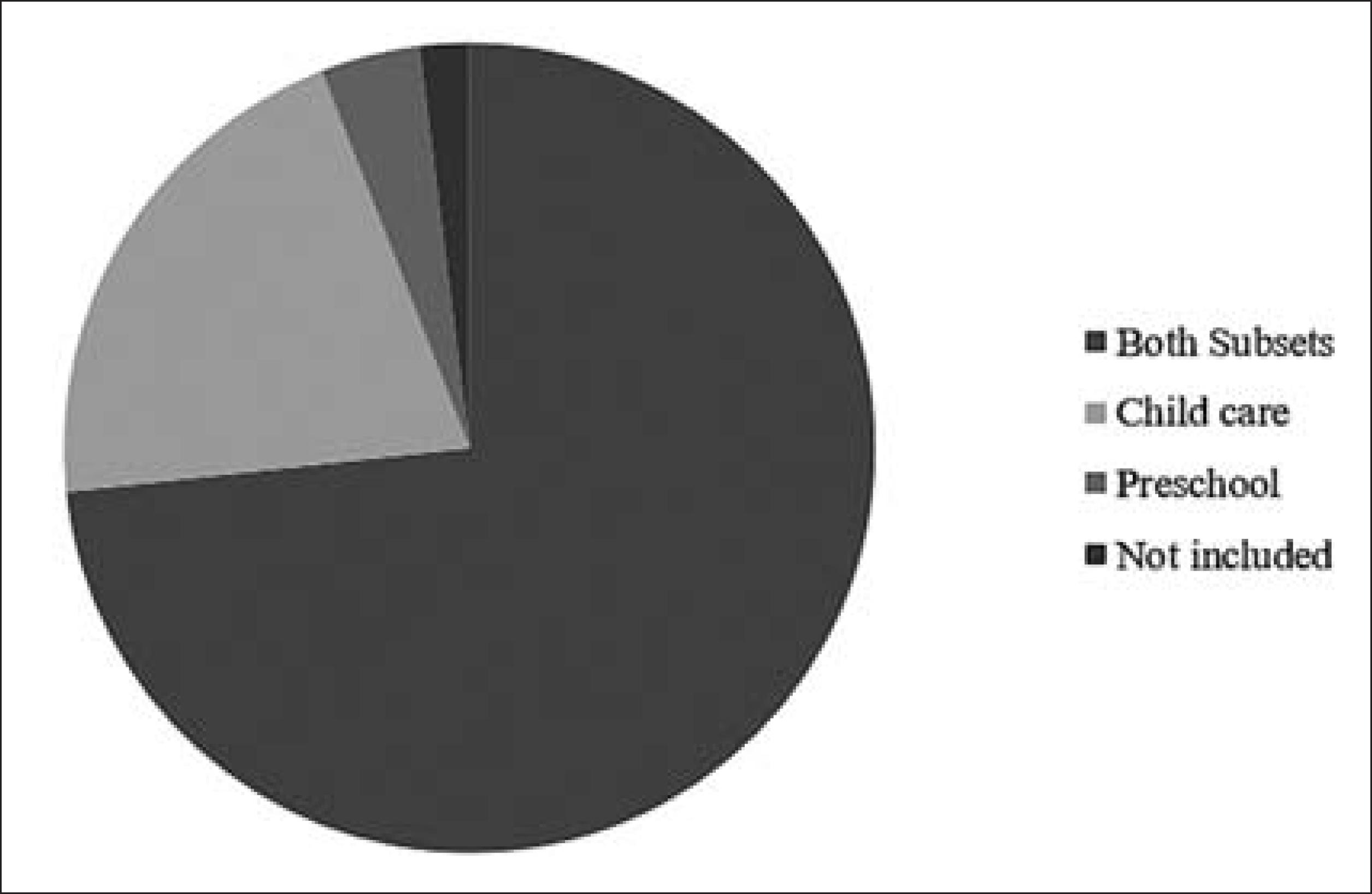

Considering that the number of collective demands has been increasing since the Constitutional Amendment 59/2009, it was sought to verify whether the actions referred to the entire early childhood education period or to just one of its substages, with emphasis on preschool, as it became compulsory due to the constitutional reform. Didonet (2014)DIDONET, Vital. A Educação Infantil na LDB/1996: mudanças depois de 2007. In: BZERZINSKI, Iria. LDB/1996 contemporânea: contradições, tensões, compromissos. São Paulo: Cortez, 2014. P. 144-170. had already pointed that the establishment of compulsory education to the age group of four and five years-old could lead to greater efforts by the government to expand the admissions in preschools, which could stagnate or even reduce the services in child care centers. However, according to the National Institute for Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira (INEP), 83.1% of children between four and five years-old attended school in 2009, and in 2014 this number grew to 89.6%, a growth rate of 7.8%. However, the percentage of children from zero to three years-old attending school in 2009 was 25.8% while in 2014 it was 33.3%, thus evidencing a considerably higher growth rate of 29% (Brasil, 2016BRASIL. Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Diretoria de Estudos Educacionais. Relatório do 1º Ciclo de Monitoramento das Metas do PNE: biênio 2014-2016. Brasília: INEP, 2016.).

Nonetheless, from the theoretical discussion held by Didonet (2014)DIDONET, Vital. A Educação Infantil na LDB/1996: mudanças depois de 2007. In: BZERZINSKI, Iria. LDB/1996 contemporânea: contradições, tensões, compromissos. São Paulo: Cortez, 2014. P. 144-170., the hypothesis was that the government would concentrate greater efforts to expanding preschools, which would in turn reduce attendance to daycare centers. This action could have propelled a larger demand for these vacancies to the Judiciary. Such hypothesis was not confirmed in the accessed data until 2014. However, as shown in Chart 4, most of the demands are proposals that aim at the access to the two substages of early childhood education. In the cases in which the expansion of the service of only one of these substages is sought, it is still possible to find a greater number of demands related to child care.

Classification of the Collective Actions that Demanded the Right to Early Childhood Education in the Brazilian Courts of Justice, Divided by Substages (2006-2016)

It is also relevant to evaluate the number of decisions made over time according to the substage required. Chart 5 indicates that decisions in the collective demands that referred to child care have been proportionally increasing in relation to all demands, whereas demands related to preschool only began to appear in 2012. Of the eleven decisions found on the right to early childhood education, specifically related to preschool, six of them discussed only the matter of the age cut as an issue for accessing the substage18 18 The decisions in the collective actions that only referred to the age cut as an issue to access primary education were not considered in this article. ; they did not allude to the matter of vacancy.

Decisions Made Over Time According to the Substage Required in the Collective Actions that Demanded the Right to Early Childhood Education in the Brazilian Courts of Justice (2006-2016)

Therefore, although the massive majority of the actions have as their subject the two substages of early childhood education, it is possible to notice that the legal requirements through collective measures have, year after year, focused more on the enforceability of child care. This movement, to a certain extent, can be characterized as an effect of the Constitutional Amendment 59/2009 (Brasil, 2009aBRASIL. Emenda Constitucional nº 59, de 11 de novembro de 2009. Acrescenta § 3º ao art. 76 do Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias para reduzir, anualmente, a partir do exercício de 2009, o percentual da Desvinculação das Receitas da União incidente sobre os recursos destinados à manutenção e desenvolvimento do ensino de que trata o art. 212 da Constituição Federal, dá nova redação aos incisos I e VII do art. 208, de forma a prever a obrigatoriedade do ensino de quatro a dezessete anos e ampliar a abrangência dos programas suplementares para todas as etapas da educação básica, e dá nova redação ao § 4º do art. 211 e ao § 3º do art. 212 e ao caput do art. 214, com a inserção neste dispositivo de inciso VI.. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 12 nov. 2009a. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/emendas/emc/emc59.htm>. Acesso em: 19 jan. 2016.

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/con...

). The amendment I sought to reduce efforts in the service at preschools, whose age range is within the compulsory education, decreasing or stabilizing vacancies in child care centers, as already reported by some researchers in the area, such as Didonet (2014)DIDONET, Vital. A Educação Infantil na LDB/1996: mudanças depois de 2007. In: BZERZINSKI, Iria. LDB/1996 contemporânea: contradições, tensões, compromissos. São Paulo: Cortez, 2014. P. 144-170.. Thus, the demand from the Judiciary can be a strategy to maintain the expansion of this substage.

Another variable identified is related to the plaintiffs. Although several entities are granted permission19 19 Law 7347/1985, which regulates the public civil actions, considers the following entities as legitimate for proposing the action: the Brazilian Public Prosecution Service, the Brazilian Public Legal Defense Service, the Union, the States, the Federal District and the Municipalities, the local authorities, public enterprises, foundations or joint stock companies and associations that fulfill the other requirements of the law (Brasil, 1985). Law 12016/2009, in turn, ensures that the collective writ of mandamus, which aims to protect collective and individual homogeneous rights, may be filed by political parties that have representatives in the National Congress, trade union organizations, class entities, or associations legally constituted and the ones that meet the other requirements of the law (Brasil, 2009b). to initiate a collective action, 92% of the actions found in this research were proposed by the Public Prosecution Service of the States. In one of the decisions, it was not possible to identify the author of the originating action. Chart 6 depicts the plaintiffs of the collective actions that were brought in the courts, which indicates the massive role of the Public Prosecution Service in the promotion of the collective right to early childhood education.

Plaintiffs in the Collective Actions that Demand the Right to Early Childhood Education, and Were Brought to the Attention of the Brazilian Courts of Justice (2006-2016)

This finding confirms what has already been stated in several studies: the Public Prosecution Service is a relevant actor in the promotion of the right to education. Silveira (2006)SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. Direito à Educação e o Ministério Público: uma análise da atuação de duas Promotorias de Justiça da Infância e Juventude do interior paulista. 2006. 262 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2006. has pointed out the importance of this institution to guarantee access to education, as well as Góes (2002)GÓES, Maria Amélia Sampaio. Educação e Cidadania: a dimensão pedagógica do Ministério Público na guarda do direito à educação de crianças e adolescentes. 2002. 169 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, 2002., who states that it is essential for raising public awareness in regards to the right to education. Feldman (2017)FELDMAN, Marina. Os Termos de Ajustamento de Conduta para efetivação do direito à Educação Infantil: considerações a partir do contexto paranaense. 2017. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Pós-Graduação em Educação da Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2017. claims that the transition of the Public Prosecution Service from the position of an auxiliary institution of the Executive Power to an essential entity in the promotion of justice was essential for this public body to determine its agenda and act in the defense and promotion of collective rights. Among those is the right to education of children and adolescents, due to the priority established in the Federal Constitution of 1988 (CF/88) and in the Brazilian Child and Adolescent Statute (ECA). This has also been indicated by Arantes (2011)ARANTES, Paulo Henrique de Oliveira. Perspectivas de Atuação do Ministério Público nas Lutas pela Efetividade do Direito à Educação Infantil. 2011. 147 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Direito) - Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Franca, 2011., who stresses the need for the institution to clarify its position regarding struggles for social rights - among which the right to early childhood education stands out.

The work of Ximenes, Oliveira and Silva (2017)XIMENES, Salomão Barros; OLIVEIRA, Vanessa Elias; SILVA, Mariana Pereira. Judicialização da Educação Infantil: efeitos e interação entre o sistema de justiça e a administração. In: REUNIÃO NACIONAL DA ANPED, 38., 2017, São Luís. Anais... São Luís: 2017. P. 1-18. Disponível em: <http://38reuniao.anped.org.br/sites/default/files/resources/programacao/trabalho_38anped_2017_GT05_1156.pdf >. Acesso em: 08 nov. 2017.

http://38reuniao.anped.org.br/sites/defa...

presents collaborative actions of several institutions in the city of São Paulo to promote the right to early childhood education. Among the entities are the Public Prosecution, Public Legal Defense, advocacy, and organizations of civil society. However, the findings of this study and the existing literature in the area indicate that the institution that works the most on the judicial demand of the right to early childhood education in a collective way is the Public Prosecution Service. This data is relevant because it was possible to notice that the other legitimized entities that are closer to the subject have made little effort to guarantee the right to early childhood education in Brazil. Rizzi and Ximenes (2010)RIZZI, Ester; XIMENES, Salomão de Barros. Litigância Estratégica para a Promoção de Políticas Públicas: as ações em defesa do direito à educação infantil em São Paulo. In: FRIGO, Darci; PRIOSTE, Fernando; ESCRIVÃO FILHO, Antônio Sérgio. Justiça e Direitos Humanos: experiências de assessoria jurídica popular. Curitiba: Terra de Direitos, 2010. P. 105-127. reinforce the importance of establishing different ways of demanding the right to early childhood education for its effective expansion and, more importantly, to increase the notion of its importance. According to the authors, this is only possible “[...] through organizations of civil society that act directly on the assistance and support of popular movements and struggles” (Rizzi; Ximenes, 2010RIZZI, Ester; XIMENES, Salomão de Barros. Litigância Estratégica para a Promoção de Políticas Públicas: as ações em defesa do direito à educação infantil em São Paulo. In: FRIGO, Darci; PRIOSTE, Fernando; ESCRIVÃO FILHO, Antônio Sérgio. Justiça e Direitos Humanos: experiências de assessoria jurídica popular. Curitiba: Terra de Direitos, 2010. P. 105-127., p. 125). Therefore, insufficient or nonexistent actions by these organizations in the judicial demand of this right may undermine the way it has been recognized, especially considering that the Judiciary rarely resorts to experts or research on education to base their decisions (Scaff; Pinto, 2016SCAFF, Elisângela Alves da Silva; PINTO, Isabela Rahal de Rezende. O Supremo Tribunal Federal e a Garantia do Direito à Educação. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 21, n. 65, p. 431-454, jun. 2016.).

It is also worth mentioning that there are still cases in which the right to early childhood education is denied by the courts. As a result, the decisions were classified based on whether or not the right to early childhood education was granted. They were distributed into three categories: the first, in which the right to early childhood education was recognized by the courts; the second, in which the right to early childhood education was denied by the courts; and the third, in which the decisions were not made due to procedural issues, although the originating actions had the right to early childhood education as subject.

This last category is relevant as it shows that there are cases that are not analyzed and therefore issues regarding the right to early childhood education are not discussed because of procedural issues. Among these issues are the impossibility of knowing of interlocutory appeals due to supervenience of sentence - which may delay the judgment of the appeals in the courts of justice -, as well as the incompetence of both the trials and the courts of appeal to judge the matter.

Chart 7 shows the number of demands that were approved, denied, and not analyzed due to procedural issues. Such data refer to the decisions by the Courts of Justice and not the decisions by first instance. With the analysis of these data, it is possible to identify a different trend from the one pointed out by Silveira (2014)SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. Exigibilidade do Direito à educação infantil: uma análise da jurisprudência. In: SILVEIRA, Adriana Dragone; GOUVEIA, Andréa Barbosa; SOUZA, Ângelo Ricardo de. Conversas sobre Políticas Educacionais. Curitiba: Appris, 2014. P. 167-188. and Corrêa (2014)CORRÊA, Luiza Andrade. A Judicialização da Política Pública de Educação Infantil no Tribunal de Justiça de São Paulo. 2014. 236 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Direito) - Pós-Graduação em Direito, Faculdade de Direito, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2014. in relation to the collective actions judged by the Court of Justice of São Paulo in comparison to the decisions issued in collective actions by all Brazilian Courts of Justice. Although a significant percentage of decisions that do not recognize the right to early childhood education is still evident, less than one fifth of the decisions deny this right.

Classification of the Decisions by the Courts of Justice in Collective Actions that Demand the Right to Early Childhood Education, in Relation to the Result of the Demand (2006-2016)

In this classification, the percentage of cases in which the right to early childhood education is still not recognized by the Brazilian Courts of Justice is noticeable. In general, the decisions are based on: issues related to the unavailable funds from the entity responsible to guarantee this right for society; on the understanding that the Judiciary’s determination to expand the offer of this educational level would result in undue interference in the Administration’s own activity (which would have the freedom to choose how this right should be fulfilled); or the non-acknowledgement of the right to education as a class right, as in cases where courts determine the need to specify children who need care in order to expand the offer.

These reasons signal the way the Brazilian Courts of Justice construct their understanding of this right. In some cases, they still link the right to education to administrative and funding issues. Therefore, in these cases, the Judiciary denies the right based on the same impediments to the fulfillment of the right pointed out by the Public Administration.

If the requests are conceded, the reasons to guarantee the right to early childhood education by STF in general do not differ from those raised by Scaff and Pinto (2016)SCAFF, Elisângela Alves da Silva; PINTO, Isabela Rahal de Rezende. O Supremo Tribunal Federal e a Garantia do Direito à Educação. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 21, n. 65, p. 431-454, jun. 2016.: it is a fundamental right and duty of the State, receiving the interference in these policies when they are not properly fulfilled by Public Administration. Likewise, the authors point out that the claim about lack of funds cannot be generically used by the Government for the non-fulfillment of the right. These facts demonstrate that there is still disagreement among the Judiciary concerning the guarantee of the right to early childhood education.

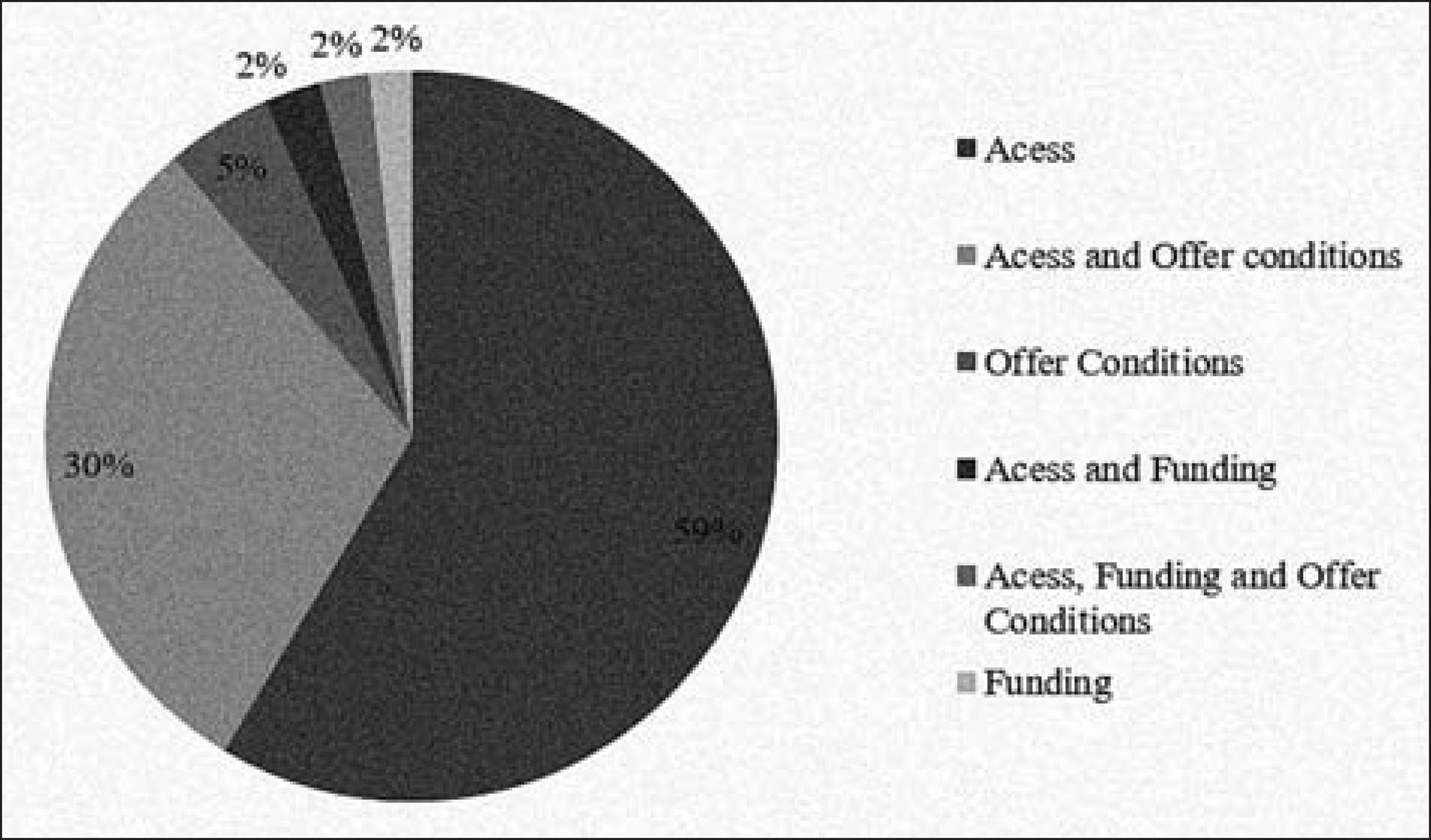

Following this, in order to analyze the merits of the decisions, they were categorized according to their content: access, funding, or offer conditions. Some decisions were not subjected to analysis due to procedural reasons, and thus, were not considered. This categorization is an initial effort aiming to understand which demands involving the right to early childhood education have been brought to the attention of the Judiciary, as well as what has been effectively used as object of trial by the Brazilian Courts of Justice.

Access-related decisions refer to cases where the requests and the discussions contained in the documents are limited to the number of vacancies, network expansion and age restriction in the access to preschool. In Chart 8, it is possible to perceive that most of the class actions fit in this category, in 59% of cases. It is important to clarify that, even if one has chosen to categorize as access the demands that require vacancies or the increase of offer, it is still considered an important dimension for the quality of early childhood education. According to Oliveira (2006)OLIVEIRA, Romulado Portela de. Estado e Política Educacional no Brasil: desafios do século XXI. 2006. 106 f. Tese (Livre-docência) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2006., the other stages of K-12 Education, particularly elementary school, have historically raised several perceptions regarding quality, since the original perception of including everyone was practically resolved. However, in the case of early childhood education, in addition to the offer not including all children in the age group, it is still extremely unequal (Rosemberg, 2015bROSEMBERG, Fúlvia. Análise das Discrepâncias entre as Conceituações de Educação Infantil do Inep e do IBGE: sugestões e subsídios para uma maior e mais eficiente divulgação dos dados. In: ARTES, Amélia; UNBEHAUM, Sandra. Escritos de Fúlvia Rosemberg. São Paulo: Cortez, 2015b. P. 241-277., p. 259). Furthermore, the expansion of access dissociated from policies that consider offer conditions will lead to the perpetuation of inequalities regarding the qualitative aspects of education (Beisegel, 2006BEISEGEL, Celso de Rui. A Qualidade do Ensino na Escola Pública. Brasília: Liber Livro Editora, 2006.). Additionally, the expansion of this offer has been determined by the Judiciary in many cases. Consequently, it seems relevant to develop research that seek to understand the effects of judicial decisions on educational policies, as well as the positive and negative aspects of this judicialization.

Classification of Decisions Issued by the Courts of Justice in Class-Action Suits with Demands for the Right to Education for Children, in Relation to the Request (2006-2016)

Funding-related decisions refer to those cases in which there was a request or establishment for savings or provision of funds to support early childhood education. The number of class actions in which these issues are discussed is evidently still too small. The decisions related to the offer conditions are those in which there are requests that discuss issues other than the availability of vacancies at this stage of education, and there are 41% of cases that fall into this category. There are offer conditions, which may be required in legal proceedings, such as those laid down in the National Curriculum Guidelines for Early Childhood Education (Brasil, 2010BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Educação Infantil. Brasília: MEC; SEB, 2010.), provisions regarding early childhood in PNE (Brasil, 2014BRASIL. Lei nº 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014. Aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação - PNE e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 26 jun. 2014. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2014/lei/l13005.htm>. Acesso em: 19 jan. 2016.

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_at...

), and the ECA, provisions regarding the minimum teacher training to work in this stage of education, as established what is laid down in the LDB, as well as the minimum wage of these professionals, according to Law 11738/2008 (Brasil, 2008BRASIL. Lei nº 11.738, de 16 de julho de 2008. Regulamenta a alínea “e” do inciso III do caput do art. 60 do Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias, para instituir o piso salarial profissional nacional para os profissionais do magistério público da educação básica. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 17 jul. 2008. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2008/lei/l11738.htm>. Acesso em: 31 out. 2016.

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_at...

). Among the class actions that discuss offer conditions to early childhood education, there are decisions related to: the proximity of residence and public transportation; technical and financial support of the states; infrastructure and construction of units; education professionals; number of children per adult; per class and minimum size; the workday and workload; and school curriculum.

Since the purpose of this study is not to analyze the specific content of each decision, it is not possible to further investigate the outcomes of the actions with or without the grant of the right pleaded in them. Nonetheless, it is possible to briefly indicate that in general the Brazilian Courts of Justice do not use distinct bases for granting or denying the right to education when analyzing questions related to the offer conditions, as previously mentioned. However, in some cases, a more serious concern is displayed by the Judiciary in relation to the rationale of these decisions, specifically analyzing the pleaded offer condition.

Among decisions related to the proximity of residence and public transportation, there were decisions that directly discussed the issue based on predictions made by the ECA, LDB, and CF/88 regarding this topic. Regarding the technical and financial support from the states, there was a need for the states to collaborate with the offer of early childhood education in the municipalities, given their financial incapacity to carry it out independently. Decisions that discussed, to a certain extent, infrastructure and the construction of units, are generally based on the principle of human dignity and on the need for a healthy, comfortable, and adequate environment for the provision of early childhood education. There are also decisions that govern the employment of education professionals in order to meet the demand and solve the existing deficit in the municipality. Decisions that discuss the adequate ratio of children per adult, per group and minimum space requested, present more qualified discussions about the right to early childhood education and the conditions of the offer, especially considering state and municipal norms and regulations by the boards of education - demonstrating how law professionals who work with education have a higher understanding of the field. The cases in which they discuss the workday and workload, in general, refer to the provision of early childhood education in full- or part-time. Regarding the curriculum, issues related to the subjects that must be offered in early childhood education were discussed. These data show how the Judiciary has been judging issues related to guaranteeing the right to education and, more specifically, early childhood education with quality. As Oliveira and Araújo (2005)OLIVEIRA, Romualdo Portela de; ARAUJO, Gilda Cardoso de. Qualidade do Ensino: uma nova dimensão da luta pelo direito à educação. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, n. 28, abr. 2005. Disponível em <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-24782005000100002&lng=pt&nrm=iso>. Acesso em: 05 ago. 2014.

http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=s...

point out, this means that there are ways to demand, to a certain extent, the provision of a good quality education before the State.

Final Remarks

As previously indicated in this work, the Judiciary has been increasingly relied upon to guarantee the right to early childhood education. This statement is confirmed by the data presented here, which show that the amount of class actions brought to the attention of the Brazilian Courts of Justice on the topic has been growing every year.

The data presented indicate a preponderance of decisions in the Southeast and Southern regions, and no decisions in class actions are found in the Courts of Justice in the states of Roraima, Ceará, Pernambuco, Piauí, and the Federal District. Therein lies an important subject to be expanded in future studies in order to identify the causes of inequality of the litigation involving early childhood education in different regions of the country.

The class requisition of the right to early childhood education is predominantly given by the Brazilian Public Ministry, which is the plaintiff in 92% of the lawsuits. Such data is relevant because it demonstrates the lack of activity of other agents in the defense of the right to early childhood education through class actions, such as Public Defender Offices and organizations of civil society. It was also verified that the most widely used instrument for the class defense of the right to early childhood education is that of a public civil action, although the legal system provides other instruments that could be used for the same purpose.

Regarding the time distribution of the demands, it was identified an increase over the years, especially following the issuance of EC n. 59/2009 (Brasil, 2009aBRASIL. Emenda Constitucional nº 59, de 11 de novembro de 2009. Acrescenta § 3º ao art. 76 do Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias para reduzir, anualmente, a partir do exercício de 2009, o percentual da Desvinculação das Receitas da União incidente sobre os recursos destinados à manutenção e desenvolvimento do ensino de que trata o art. 212 da Constituição Federal, dá nova redação aos incisos I e VII do art. 208, de forma a prever a obrigatoriedade do ensino de quatro a dezessete anos e ampliar a abrangência dos programas suplementares para todas as etapas da educação básica, e dá nova redação ao § 4º do art. 211 e ao § 3º do art. 212 e ao caput do art. 214, com a inserção neste dispositivo de inciso VI.. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 12 nov. 2009a. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/emendas/emc/emc59.htm>. Acesso em: 19 jan. 2016.

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/con...

). Although most of the demands do not distinguish between the substage of early childhood education for which the right is pleaded, in cases where specifically one of the stages is required, the highest number of requests refers to daycare centers. These data require further research, as they may be a result from the Public Administration’s prioritization of the service for preschool, made compulsory by the EC n. 59/2009, that could indicate a reduction in the service for daycare, which would justify greater Judicial effort to guarantee the quality of preschool. The actions in which the right to preschool is specifically discussed are, in general, more related to the age group than to the increase of access.

There are still cases in which the right to early childhood education is denied, representing 18% of the decisions covered by this research. Among these cases, it was possible to identify some in which the right was denied for the impossibility of granting a generic and abstract request. These were cases in which the plaintiffs required the extension of access or service without specifying the number of necessary vacancies or without indicating the children who had their enrollments denied by the Government.

This reason for denying the law draws attention because it acknowledges the right to education only as a homogeneous individual right, which requires that its holders be specified for protection reasons. This difficulty, as reported by Lopes (2002, p. 129)LOPES, José Reinaldo de Lima. Direito Subjetivo e Direitos Sociais: o dilema do judiciário no estado social de direito. In: FARIA, José Eduardo (Org.). Direitos Humanos, Direitos Sociais e Justiça. São Paulo: Malheiros Editores, 2002., “[...] derives from the social model of the market, which corresponds to a legal form of interpersonal relationships”. This demonstrates that resistance to the recognition of the right to education, whether as a social right or as a class right is still facing resistance, as pointed out by Silveira (2014)SILVEIRA, Adriana Aparecida Dragone. Exigibilidade do Direito à educação infantil: uma análise da jurisprudência. In: SILVEIRA, Adriana Dragone; GOUVEIA, Andréa Barbosa; SOUZA, Ângelo Ricardo de. Conversas sobre Políticas Educacionais. Curitiba: Appris, 2014. P. 167-188. and Corrêa (2014)CORRÊA, Luiza Andrade. A Judicialização da Política Pública de Educação Infantil no Tribunal de Justiça de São Paulo. 2014. 236 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Direito) - Pós-Graduação em Direito, Faculdade de Direito, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2014.. However, this position is far from unanimous, since it was also possible to find decisions in similar cases in which the right was recognized by the courts.

Attention is also drawn to the fact that, in 19% of cases, the Courts of Justice did not discuss the merits related to the right to early childhood education due to procedural issues. Although procedural right is recognized as essential to the fulfillment of the right, these data show that, in Brazilian courts, it is an obstacle to the discussion about the content of the right to early childhood education on several occasions.