ABSTRACT

This study explores the relationship between social media influencers (SMIs), overconfidence (OC), and aggressive investor behavior (AIB), with a particular focus on gender differences, addressing the limited research on this topic. Using data from 420 investors in Indonesia, collected through a questionnaire and analyzed using structural equation modeling, this research examines three key objectives: the direct effect of SMIs and OC on AIB, the mediating role of OC, and the moderating effect of SMIs across genders. The results reveal that both SMIs and OC significantly influence AIB for both men and women, with OC serving as a mediator. Notably, the effect of SMIs on OC, which in turn drives AIB, is stronger among women than men. These findings contribute to the advancement of financial behavior theory and market microstructure theory by clarifying the role of SMIs and OC in shaping AIB. Beyond theoretical contributions, the results also highlight potential social impact in the Global South, particularly for female investors, who may experience financial losses and increased household-level economic stress, with broader potential to deepen existing socio-economic inequalities.

Keywords:

aggressive investor; overconfidence; social media influencer; market microstructure theory; behavioral finance.

RESUMO

Este estudo explora a relação entre os influenciadores de redes sociais (IRS), o excesso de confiança (EC) e o comportamento agressivo dos investidores (CAI), com especial incidência nas diferenças de gênero, contribuindo para cobrir a lacuna de estudos sobre esse tema. Utilizando dados de 420 investidores na Indonésia, obtidos por meio de um questionário e analisados a partir de modelagem de equações estruturais, o estudo examina três objetivos principais: o efeito direto dos IRS e do EC no CAI, o papel mediador do EC e o efeito moderador dos IRS no que diz respeito a questão de gênero. Os resultados revelam que tanto os IRS como o EC influenciam significativamente o CAI, tanto para os homens como para as mulheres, com o EC servindo de mediador. Nomeadamente, o efeito dos IRS sobre o EC, que, por sua vez, conduz a um CAI, é mais forte nas mulheres do que nos homens. Esses resultados contribuem para o avanço da teoria do comportamento financeiro e da teoria da microestrutura do mercado, clarificando o papel dos IRS e do EC na formação do CAI. Para além da contribuição teórica, os resultados também destacam o potencial impacto social no Sul Global, em particular para as mulheres investidoras, que podem sofrer perdas financeiras e um aumento do estresse econômico no nível do agregado familiar, com um potencial mais amplo para aprofundar as desigualdades socioeconômicas existentes.

Palavras-chave:

investidor agressivo; excesso de confiança; influenciador de mídias sociais; teoria da microestrutura de mercado; finanças comportamentais.

RESUMEN

Este estudio explora la relación entre los influenciadores de redes sociales (IRS), el exceso de confianza (EC) y el comportamiento agresivo del inversor (CAI), con especial incidencia en las diferencias de género, lo que contribuye a llenar el vacío de investigación sobre este tema. Utilizando datos de 420 inversores en Indonesia, obtenidos a través de un cuestionario y analizados mediante modelos de ecuaciones estructurales, el estudio examina tres objetivos principales: el efecto directo de los IRS y el EC en el CAI, el papel mediador del EC y el efecto moderador de los IRS con respecto al género. Los resultados revelan que tanto los IRS como el EC influyen significativamente en el CAI tanto para los hombres como para las mujeres, con el EC sirviendo como mediador. En particular, el efecto de los IRS sobre el EC, que a su vez conduce a un CAI, es más fuerte en las mujeres que en los hombres. Estos resultados contribuyen al avance de la teoría del comportamiento financiero y de la teoría de la microestructura del mercado al aclarar el papel de los IRS y del EC en la formación del CAI. Más allá del aporte teórico, los resultados también resaltan el potencial impacto social en el sur global, particularmente para las mujeres inversionistas, quienes pueden experimentar pérdidas financieras y mayor estrés económico a nivel del núcleo familiar, con un potencial más amplio de profundizar las desigualdades socioeconómicas existentes.

Palabras clave

inversor agresivo; exceso de confianza; influenciador de redes sociales; teoría de la microestructura de mercado; finanzas conductuales.

INTRODUCTION

Research on the impact of gender in financial decision-making has become a significant field of study, highlighting clear behavioral differences between male and female investors. These differences can significantly impact the decisions made in financial contexts, leading to varied outcomes in financial markets (Haag & Brahm, 2025). Examining the role of gender dynamics in shaping choices is crucial for achieving a complete understanding of investor conduct. Investors exhibit a combination of rational and irrational behaviors, which significantly influence their decision-making in stock markets (McCartney et al., 2021). Although individuals often strive for rationality, behavioral finance demonstrates that emotions, mental biases, and environmental influences-including social signals-can significantly shape their decisions (Shiller, 2003). Although existing studies have thoroughly examined investor conduct through limit order book (LOB) analysis (O’Hara, 2015), the relationship between cognitive biases - for instance, overconfidence (Barber & Odean, 2001) - and market microstructure theory remains underexplored, particularly for aggressive trading strategies. Research on LOB primarily emphasizes liquidity provision (Biais et al., 2005) or price discovery (Glosten, 1994), frequently neglecting the systematic influence of cognitive biases on aggressive order submission (market orders). This oversight is significant since aggressive trading intensifies market fluctuations (Kyle, 1985) and disrupts liquidity conditions (Chordia et al., 2001), while existing theoretical frameworks (Foucault et al., 2005) seldom account for variations in investor psychology. This study bridges this divide by empirically testing how overconfidence (OC) - measured via trading frequency moderates the microstructure-aggression link, a relationship previously postulated but untested. Aggressive investors tend to prioritize immediate execution by using market orders, while non-aggressive investors place limit orders, aiming to secure more favorable prices by entering bids and offers into LOB (Rizal et al., 2024). This model represents a novel approach that is rarely explored in existing literature. The novelty of the current model lies in its dual-path mechanism that examines both the direct effect of social media influencers (SMIs) on aggressive investor behavior (AIB) and the mediating role of OC, with analysis conducted separately for male and female investors. Compared to existing models that often isolate psychological or demographic factors (Bao & Li, 2020; Musnadi et al., 2025), this framework offers a more nuanced explanation of behavioral mechanisms in modern financial environments shaped by digital influence.

Excessive self-assurance represents a thoroughly studied cognitive bias in both psychological research and financial markets (Ghani et al., 2023). This bias causes market participants to overvalue favorable information, overlook potential dangers, and increase their trading activity (Abreu & Mendes, 2012). This tendency may drive security valuations above their fundamental worth, possibly leading to the formation of speculative market bubbles (Sood & Sharma, 2022). While OC may lead to bold purchasing decisions, it often results in poorer portfolio performance (Annick, 2020). These effects are especially relevant when considering aggressive investors who prioritize fast execution, typically using market orders over limit orders (Mitchell & Chen, 2020).

Additionally, SMIs are increasingly affecting investor behavior. Academic research shows that social media has a profound impact on decision-making, risk perception, and herding behavior (Singh & Sarva, 2024). The emotional appeal and network effects of influencer marketing also shape investor sentiments, directly influencing how they perceive risks and opportunities (Haase et al., 2023). This phenomenon highlights the importance of external social cues in shaping financial decisions, particularly in volatile markets.

When analyzing investor behavior through the lens of gender differences, distinct patterns emerge in how men and women approach risk and decision-making. Men typically display higher levels of OC and are more likely to take risks in financial markets (Lawrence et al., 2024), often leading to more frequent trading. Female investors typically exhibit greater prudence, emphasizing thorough evaluation and risk mitigation in their decision-making (Lawrence et al., 2024). Studies consistently demonstrate these gender-based differences in financial decision-making. Barber and Odean (2001) found that men, driven by OC, tend to trade more frequently, which can often lead to lower returns. Beyond gender-related variations, the increasing influence of social platforms on investment choices introduces additional complexity. SMIs significantly shape investor behavior, frequently intensifying OC and AIB (Musnadi et al., 2025).

This study seeks to address three main research objectives. First, it aims to analyze the direct influence of SMIs and OC on AIB among male and female investors. Second, it examines how OC mediates the effect of SMIs on aggressive behavior while considering gender differences. Finally, it evaluates the moderating role of SMIs in the relationship between OC and AIB, emphasizing how these effects differ between men and women.

This study offers key contributions to behavioral finance by examining gender differences in AIB-specifically through market orders-and revealing how psychological biases like OC vary across genders. The study further expands market microstructure theory by investigating how SMIs affect the relationship between OC and aggressive trading, highlighting the influence of digital information flow. By integrating both perspectives, the study presents a comprehensive model capturing direct and mediated effects, while uncovering gender-specific behavioral patterns. This cross-disciplinary perspective enhances comprehension of how psychological and informational factors jointly drive investor decisions in today’s financial markets. The results indicate that OC mediates the impact of SMIs on AIB across genders. Notably, gender differences were observed: for female investors, SMIs significantly amplify the effect of OC on aggressive trading behavior, whereas for male investors, this effect is not significantly intensified on the Indonesia Stock Exchange. These insights contribute to financial behavior theory, particularly prospect theory and OC bias.

This study commences with a presentation of the study's background, followed by a comprehensive literature review. The study then describes the methodological approach before presenting results accompanied by analytical interpretation. Finally, the conclusions, implications, and limitations are presented.

LITERATURE REVIEW

This section offers details on the variables under study and a comprehensive literature review.

Behavioral finance theory

Behavioral finance examines how psychological factors and cognitive biases influence investor behavior and market outcomes, challenging the traditional view of rational decision-making. Investors are often swayed by emotions, leading to irrational choices. For example, overconfidence (OC) - a common bias - causes investors to overestimate their knowledge and underestimate risk, resulting in excessive trading and poor returns (Barber & Odean, 2001). A key theory in this field is Prospect Theory (Costa et al., 2019), which explains that individuals perceive losses more intensely than equivalent gains, leading to loss aversion-risk-averse behavior in gains and risk-seeking behavior in losses.

Beyond cognitive biases, demographic factors-particularly gender-also influence investor behavior. Studies show that women tend to be more risk-averse than men, shaping their investment decisions and financial strategies (Baker et al., 2019). Information-seeking behavior also differs, with some demographics being more proactive in data analysis before investing. These variations can lead to different financial outcomes, underscoring the need for personalized financial guidance (Musnadi et al., 2025). By combining psychological and financial insights, behavioral finance offers a deeper understanding of market behavior, with practical value for practitioners and policymakers.

Market microstructure theory

Market microstructure theory explores the intricate mechanisms governing trading activities within capital markets, encompassing the processes, regulations, and market fairness that influence asset exchanges and price formation (Harris, 2004; Stoll, 2002). Central to this theory is the concept of the Limit Order Book (LOB), where orders to buy or sell securities are recorded and executed based on specific conditions

Investors participating in capital markets are typically categorized into two main groups: active and passive. Active investors, often referred to as aggressive investors, prefer using market orders. These orders allow them to execute transactions immediately at the prevailing market prices (Harris, 2004; Stoll, 2002). On the other hand, passive investors, known for their patient approach, use limit orders. These orders are placed at specified prices and wait in a queue until market conditions meet their criteria for execution. Market orders prioritize speed and immediate execution at the current market price, enabling investors to capitalize on short-term opportunities (Tripathi et al., 2020).

Aggressive investor behavior (AIB) is characterized by a preference for market orders, reflecting their proactive stance in swiftly executing transactions to capitalize on immediate market opportunities. In contrast, non-aggressive investors opt for limit orders, demonstrating a more cautious approach that aligns with their desired price levels and market conditions (Hung et al., 2015).

Social media influencers and aggressive investor behavior

Social media influencers (SMIs) have become key figures in shaping consumer behavior across various domains, including finance and investment. Studies have shown that influencers' credibility-encompassing attractiveness, expertise, and trustworthiness-plays a crucial role in shaping followers' perceptions and decisions (Sathya & Prabhavathi, 2024). SMIs create an interactive environment where followers feel engaged and connected, often leading to heightened trust and reliance on their information for decision-making (Singh & Sarva, 2024). This influence is particularly relevant in financial contexts, as information provided by SMIs can shape investors' risk perceptions, attitudes, and even drive aggressive transaction behaviors through the use of market orders (AIB). Given the prevalence of SMIs in Indonesia (AnyMind, 2023), their impact on investor behavior on the Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX) merits further investigation.

Previous research has demonstrated that SMIs influence investor decisions by leveraging credibility and relatability (Pandey & Guillemette, 2024). However, gender plays a critical role in shaping investor responses to SMIs-driven content and financial decision-making. Sociocultural factors and traditional gender roles significantly influence risk-taking tendencies and investment behavior, leading to notable differences between male and female investors (Sekścińska et al., 2023).

Men tend to exhibit higher risk tolerance and confidence in their investment decisions, while women are generally more cautious and prioritize financial security (Walczak & Sylwia, 2018). Furthermore, women demonstrate greater engagement with social media advertisements and are more susceptible to their influence, suggesting distinct patterns in how financial advice and marketing messages shape investment behaviors (Asogwa et al., 2020) and that these differences extend to decision-making contexts influenced by SMIs (Al-Shehri, 2021). Mawad and Freiha (2024) further highlight that gender-based differences shape how individuals respond to influencer content in financial decision-making. Given that men are more likely to invest in high-risk financial assets such as stocks and bonds (Long & Tue, 2024), it is reasonable to assume that SMIs may reinforce aggressive investment behavior among male investors more significantly than among women.

The presence of SMIs was found to significantly affect AIB, with Bandarmology information (market maker analysis) having a positive and significant effect on AIB on the Indonesia Stock Exchange (Musnadi et al., 2025). Based on these insights, we hypothesize that:

-

H1a-H1b: SMIs affect aggressive investors’ behavior among male-(H1a) / Female-(H1b) investors on the Indonesia Stock Exchange.

Social media influencers and overconfidence

OC, a widely observed behavioral bias in financial markets, refers to investors’ tendency to overestimate their knowledge, skills, and control over outcomes (Ghani et al., 2023). Empirical studies have demonstrated that overconfidence can lead to more aggressive investment decisions and risk-taking behavior (Werner et al., 1985). The role of SMIs in potentially enhancing OC among investors has also been discussed in recent literature, particularly as influencers may create overly optimistic perceptions and encourage high-risk behaviors among their followers (Singh & Sarva, 2024).

Gender differences in OC are well-documented, with men generally exhibiting higher levels of OC in financial decisions compared to women (Barber & Odean, 2001). Given this, it is plausible that SMIs might influence male and female investors’ confidence levels differently, with male investors potentially being more susceptible to heightened OC due to pre-existing tendencies toward risk-taking and assertiveness in financial matters. Furthermore, gender differences in susceptibility to behavioral biases such as OC and herding behavior influence how men and women engage with investment-related content on social media (Jamil & Khan, 2016). Based on these insights, we hypothesize that:

-

H2a-H2b: SMIs affect the OC of male-(H2a) / female-(H2b) investors on the Indonesia Stock Exchange.

Overconfidence and aggressive investor behavior

OC significantly influences AIB, as investors who overestimate their ability to predict market trends are more likely to adopt high-risk strategies and use market orders (Musnadi et al., 2025). This bias often leads to frequent trading in pursuit of higher returns. Behavioral finance research confirms that OC increases both the frequency and riskiness of trades (Parveen et al., 2020). Moreover, gender differences in risk tolerance suggest that OC affects male and female investors differently (Barber & Odean, 2001).

Social media platforms further amplify these differences by providing vast amounts of information, which can lead to miscalibration and the disposition effect, ultimately reinforcing OC (Nair & Shiva, 2023). Younger male investors, particularly those with lower portfolio values and from low-income regions, are especially susceptible to OC. The presence of social media exacerbates this tendency, as these investors may heavily rely on influencer-driven content when making investment decisions (Nair & Shiva, 2023). Likewise, Inghelbrecht and Tedd (2024) find that social media-driven OC encourages excessive trading, ultimately harming portfolio performance. These findings highlight how OC fueled by SMIs can drive aggressive trading without guaranteeing long-term gains.

Additionally, research shows that OC mediates the link between information and investment decisions (Khan et al., 2019). As key financial information sources, SMIs may further amplify this bias, reinforcing impulsive and high-risk trading behavior. Building on this theoretical and empirical foundation, we hypothesize that:

-

H3a-H3b: OC affects AIB among male- (H3a) / Female-(H3b) investors on the Indonesia Stock Exchange.

The mediating role of overconfidence in SMIs-driven aggressive investor behavior

The relationship between SMIs and AIB is posited to operate through a mediated pathway involving OC, with nuanced variations across demographic factors. Recent empirical work by Musnadi et al. (2025) demonstrates that OC serves as a significant mediator between various information sources and trading aggression, with the strength of this mediation contingent upon investor characteristics, including domicile, education level, and marital status. This mediation effect stems from the well-documented tendency of overconfident investors to attribute successful outcomes to their own skill rather than external factors or market conditions (Bao & Li, 2020). Social media platforms exacerbate this cognitive bias through several interconnected mechanisms: the constant flow of financial information creates an illusion of comprehensive market knowledge (Nair & Shiva, 2023). These dynamics are particularly pronounced in emerging market contexts like Indonesia, where high social media penetration intersects with varying levels of financial literacy across demographic groups (Ambarwati et al., 2024). The resulting environment fosters excessive trading activity, as investors-bolstered by misplaced confidence in their analytical abilities-engage in frequent transactions despite the associated costs and risks (Khan et al., 2019). Gender-based differences in information processing and risk perception further suggest that, while OC mediates the relationship between exposure to SMIs and trading aggressiveness in both groups, the underlying psychological mechanisms and resultant behaviors differ significantly. Building on this theoretical and empirical foundation, we hypothesize that:

-

H4a-H4b: OC mediates the effect of SMIs on AIB among male-(H4a) / female-(H4b) investors on the Indonesia Stock Exchange.

The moderating role of social media information

The pervasive availability of social media information amplifies the tendency of investors toward OC and AIB, as high-frequency updates can lead investors to overreact to incoming information, often neglecting underlying risks. Research by Nair and Shiva (2023) provides insights into how information obtained on social media can intensify OC biases among retail investors by disseminating biased or selectively favorable information. This OC can increase investors' propensity to make aggressive trades. However, Nair and Shiva (2023) also discuss how regulatory interventions and disclosure requirements can mitigate such biases, reducing the influence of social media information on investment decisions by encouraging more balanced information dissemination. Considering the influence of this information on investor OC and aggressive trading behavior, it is important to further examine how SMIs shape investor decision-making, particularly in the context of aggressive investment tendencies.

Beyond its role as an information source, social media also serves as a dynamic platform for peer interaction, further shaping investor sentiment and behavior. Ambarwati et al. (2024) suggest that engagement in social media investment communities fosters a sense of increased knowledge and validation, strengthening investors' confidence in their trading decisions. However, this reinforcement effect can inadvertently fuel OC, prompting riskier investment strategies and more frequent trading activity. Additionally, social media has been found to influence cognitive biases such as miscalibration and the disposition effect, further shaping how investors process and act on financial information (Nair & Shiva, 2023).

Empirical studies further confirm that while social media enhances market accessibility, it also exacerbates behavioral biases, including herding tendencies and OC, which can distort risk perception and lead to irrational investment decisions (Sathya & Prabhavathi, 2024). These findings underscore the dual role of social media in financial markets, it can serve as both an enabler of informed decision-making and a catalyst for behavioral distortions. To further explore the influence of social media on investor behavior, we propose the following hypotheses:

-

H5a-H5b: SMIs moderates the effect of OC on AIB among male-(H5a) / female-(H5b) investors on the Indonesia Stock Exchange.

METHODOLOGY AND DATASET

This study employed a questionnaire on aggressive investor behavior (AIB), adapted from prior research on overconfidence (OC) and investor information sources (Rizal et al., 2024). A total of 420 responses were collected from investors across five major Indonesian islands-well above the minimum SEM requirement of 120 (Hair et al., 2019). The questionnaire included 24 behavior-related items, with a sample comprising 51% male (216) and 49% female (204) respondents. Data were gathered using a multistage purposive random sampling method.

A multistage sampling method was used to capture Indonesia’s geographically dispersed investor population. Referring to KSEI data (June 2022) with over 9 million investors, the sample was proportionally drawn from five regional clusters: Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Java-Bali-NTT-NTB, and Maluku-Papua. Data were collected online via Google Forms, mainly in urban areas through social media and investment forums, targeting investors more actively engaged with social media influencers (SMIs). A screening question confirmed that respondents were active traders.

To ensure the model produces reliable and meaningful results, several tests were conducted. These included checks for multicollinearity, validity, reliability, and indicator strength. The overall model fit was also evaluated using measures such as R2, F2, Q2, and SRMR. Additionally, the model was submitted to a predictive ability test (CVPAT). These steps help confirm that the model fits the data well and provides a solid basis for further analysis (Hair et al., 2019).

For data analysis, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was used due to its strength in predictive research and suitability for complex models with small to medium sample sizes. Unlike CB-SEM, which emphasizes theory confirmation through covariance, PLS-SEM focuses on theory testing from a predictive perspective (Hair et al., 2019). Moreover, PLS-SEM was appropriate for this study as it does not assume multivariate normality, aligning with the non-normal distribution of the data.

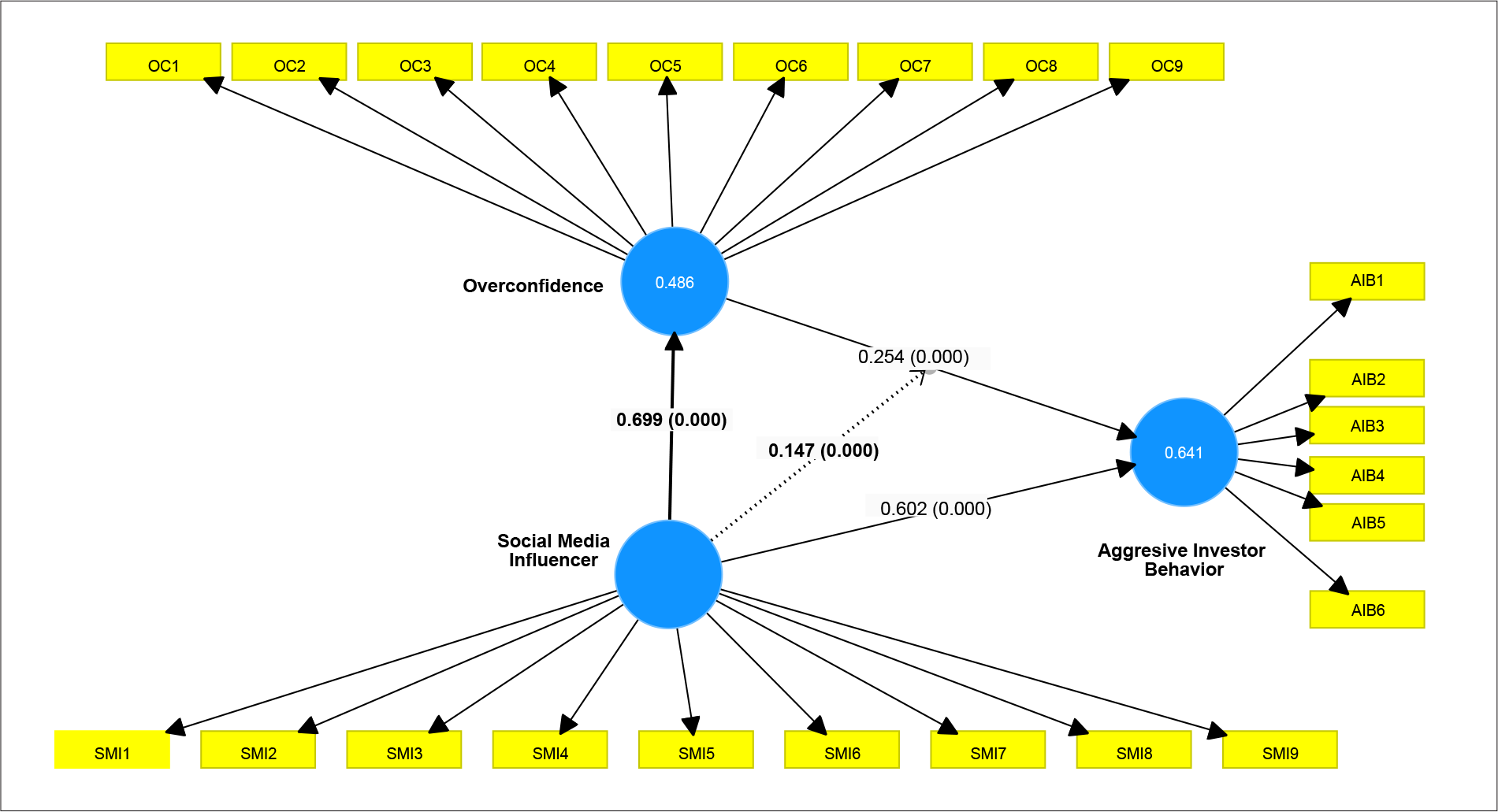

The structural model presented in Figure 1 depicts the research construct model.

The operational variables in this study are defined as follows. Gender was identified through a questionnaire item. OC, a behavioral bias in financial decisions, reflects investors' tendency to overestimate their abilities and the accuracy of the information they receive. This construct is measured using three dimensions: overestimation, overplacement, and overprecision (Rizal et al., 2024). SMIs are individuals with substantial influence on social platforms, capable of shaping followers' attitudes, behaviors, and decisions through consistent engagement (AlFarraj et al., 2021). Influencer credibility is assessed using Ohanian's (1990) dimensions: attractiveness, expertise, and trustworthiness-factors that remain central to academic discussions on SMIs impact.

The dependent variable, AIB, refers to the use of market orders for immediate execution in a limit order book (LOB) under various market conditions (Rizal et al., 2024). Measurement items for all variables are presented in Table 1.

ANALYSIS OF RESEARCH RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 2 shows the correlation and descriptive statistics results. All variables are strongly correlated (r > 0.6), and the standard deviations for overconfidence (OC), social media influencers (SMIs), and aggressive investor behavior (AIB) exceed 0.7, indicating substantial response variation.

Measurement model

The structural measurement analysis followed Latif et al. (2022), including tests for multicollinearity, discriminant validity, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and loading factors. Results are presented in the tables below.

The correlation analysis among the research variables indicates the absence of multicollinearity, which is suspected when correlation values exceed 0.90. In this study, the correlation values between the variables were below 0.90, and we assessed collinearity using VIF, following Hair et al. (2019), who suggest that VIF values below 5 indicate no multicollinearity concerns. The results confirm the absence of multicollinearity. Subsequently, the measurement model results are presented in Table 3:

The results (Table 3) show that the measurement model is valid and reliable for all variables-OC, SMIs, and AIB. As shown in Table 3, all items met this criterion, confirming their suitability for further analysis. Discriminant validity, assessed using the AVE root comparison (Table 4), also confirms the model’s robustness. These findings highlight the model’s suitability for analyzing AIB, OC, and SMIs in the Indonesian stock market context.

Table 4 shows that the square roots of AVE for all constructs exceed their inter-construct correlations, meeting the Fornell-Larcker criterion for discriminant validity (Sekaran & Bougie, 2011). The square root of AVE for AIB (0.849) is greater than its correlations with OC (0.662) and SMIs (0.747); OC (0.822) exceeds its correlations with AIB and SMIs (0.738); and SMIs (0.840) is higher than its correlations with AIB and OC. These results confirm that all constructs are distinct and theoretically valid.

Structural model

To test the theoretical model, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used, covering both measurement and structural model evaluations. Following the two-stage approach, the model’s goodness of fit was first assessed, followed by structural testing. The proposed SEM equation applies the fit indices recommended by Lei and Lomax, (2005). R2, F2, Q2, and collinearity results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5 shows that R2 values for AIB (0.592) and OC (0.545) indicate moderate explanatory power. Q2 values for both variables exceed 0.50, reflecting high predictive accuracy, as values above 0.50 signify high accuracy. The F2 values reveal that only SMIs have a moderate effect on AIB (F2=0.02-0.15) (Hair et al., 2019).

The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) value of 0.053 for AIB suggests a good fit of the model. Overall, these results demonstrate that the model adequately fits the data and has strong explanatory and predictive power. After ensuring that all indicators are valid and reliable and the proposed estimation model meets the criteria, the research proceeds to the next stage by testing the proposed hypotheses. The findings of hypothesis testing are reported in the next section.

In addition to SRMR, model fit was evaluated using PLS-SEM with the Cross-Validated Predictive Ability Test (CVPAT), which compares predictive accuracy against two benchmarks: the indicator average (IA) and a linear model (LM). The PLS-SEM model demonstrated significantly better predictive performance than the IA model (-0.356), while the difference with the LM model was small and statistically non-significant (-0.002). Therefore, although the model clearly outperforms the IA benchmark, the non-significant difference with LM means it cannot be conclusively stated that the PLS-SEM model is superior to the LM benchmark (Guenther et al., 2023). It might initially suggest limited predictive capability. This single metric should not overshadow the model's overall validity, as CVPAT constitutes just one component of comprehensive model evaluation (Hair et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the PLS predict results in Table 5 show the model’s advantage, with PLS-SEM RMSE values outperforming LM benchmarks across most indicators, despite indicating low predictive power. All Q2 predict values above zero confirm its ability to exceed naive predictions, supporting its practical relevance. Overall, the model remains statistically valid and theoretically meaningful, despite some room for improvement in predictive strength. However, it provides a statistically sound and theoretically meaningful framework for understanding the examined phenomena.

Path analysis and hypothesis testing

Structural model evaluation assesses the significance of path coefficients, which are considered significant if the t-value exceeds 1.96. This confirms the strength and validity of relationships within the model.

Table 6 shows the direct effects of SMIs and OC on AIB in the Indonesian stock market.

The results show that SMIs and OC significantly influence AIB in both genders. The SMI effect on AIB is significant for both (β = 0.689, p = 0.000 for men and β = 0.602, p = 0.000 for women), confirming hypotheses H1a and H1b.

The direct effect of SMIs on OC is significant for men (0.751, p-value 0.000) and women (0.699, p-value 0.000), thus supporting hypotheses H2a and H2b. Additionally, the direct effect of OC on AIB is significant for men (0.172, p-value 0.000) and women (0.254, p-value 0.000), supporting hypotheses H3a and H3b. It also indicates that the influence of OC on AIB is stronger among female investors.

In terms of indirect effects, OC mediates the relationship between SMIs and AIB for both men (0.129, p-value 0.000) and women (0.178, p-value 0.000), supporting hypotheses H4a and H4b. These findings underscore the critical mediating role of OC, particularly among female investors, demonstrating a partial mediation effect. In the context of information provided by SMIs, female investors demonstrated to be more influenced in terms of OC compared to their male counterparts.

This outcome aligns with previous research demonstrating that OC can serve as a mediating variable for various types of information, including historical price information, technical, and fundamental information, in influencing investor decision-making (Begum & Siddiqui, 2024; Musnadi et al., 2025). The mediating role of OC in this study underscores how information from SMIs can elevate investor OC, ultimately leading investors to use market orders in their transactions.

However, these findings differ from earlier research on gender and OC. Mishra and Metilda (2015) found that men generally exhibit higher levels of OC compared to women, while this study reveals that women show a stronger mediating effect in the influence of SMIs on AIB. This discrepancy could be due to specific factors such as cultural context or social roles, which may shape gender-specific responses to information from influencers.

The analysis of moderating effects reveals a gender difference. For male investors, the interaction between SMIs and OC does not significantly affect aggressive behavior (-0.024, p-value 0.518), leading to the rejection of hypothesis H5a. Conversely, for female investors, this interaction significantly impacts aggressive behavior (0.147, p-value 0.000), supporting hypothesis H5b. This suggests that the combined influence of SMIs and OC is more pronounced in female investors. Our study demonstrates that SMIs significantly impact aggressive trading behavior through distinct gender-based mechanisms. While both male and female investors show direct effects of SMIs exposure on AIB (supporting H1a/H1b), the psychological pathways differ fundamentally. For women, SMIs primarily operate by amplifying OC, which then drives aggressive trading (supporting H4b/H5b). These outcomes suggest that the type of moderation for female investors falls under the category of quasi-moderation, as the variable (SMIs x OC) serves as both a moderating and an exogenous variable simultaneously. This mediated pathway accounts for most of the influence of SMIs on AIB for women. In contrast, for men, SMIs affect AIB directly, without significantly interacting with OC levels (H5a rejected). These results reveal that AIB for women is particularly sensitive to confidence-driven influences from SMIs, while male investors respond more to the informational content itself, regardless of confidence effects.

DISCUSSION

The results reveal that overconfidence (OC) significantly mediates the relationship between social media influencers (SMIs) and aggressive investor behavior (AIB), indicating a partial mediation effect. This highlights OC as a key channel through which SMIs influence investor decisions. Consistent with Abreu and Mendes (2012), this study finds that increased information acquisition often leads to higher trading activity, driven by OC in perceived knowledge. Exposure to SMIs, who typically project confidence and success, reinforces this bias, prompting more frequent and aggressive trading. This amplification effect is key to understanding investor behavior in a digital market shaped by social media influence. Research by Bian et al. (2018) emphasizes that behavioral biases induced by OC significantly influence AIB in stock transactions. The study's findings further support a partial mediation effect, indicating that while SMIs directly impact AIB, a substantial part of this influence is mediated through the enhancement of investor OC.

Moreover, studies on the influence of SMIs on OC and investor decision-making reveal significant impacts. Research by Adebambo and Yan (2018) suggests that firms with overconfident investors may initially be overvalued, potentially leading to lower subsequent stock returns. Conversely, Inghelbrecht and Tedde (2024) demonstrate that overconfident investors influenced by social media tend to engage in excessive trading and reduce overall portfolio returns.

Recent studies underscore the intricate dynamics between OC as a mediator and SMIs as moderators in shaping investor behavior. OC mediates the relationship between informational inputs and investor decisions (Khan et al., 2019). Moreover, the moderation effect of SMIs highlights their role in either exacerbating or mitigating OC-driven behaviors among investors. Nair and Shiva (2023) provide insights into how SMIs can amplify OC biases among retail investors through biased information dissemination. Conversely, regulatory interventions and disclosure requirements have shown potential in mitigating these behaviors, thereby tempering the influence of SMIs on investment decisions.

Gender differences significantly influence responses to SMIs and their financial decisions. Studies highlight that sociocultural factors and gender roles play pivotal roles in shaping risk-taking propensities and investment behaviors among men and women (Sekścińska et al., 2023). Moreover, the effects of SMIs on male and female investors differ markedly. Women tend to engage more deeply with social media advertisements and are more influenced by such content, suggesting varying responses to marketing messages and financial advice disseminated through social platforms (Asogwa et al., 2020). Further studies could explore these factors in greater depth, including the role of social norms, the intensity of social media engagement, and prior investment experience, to better understand the mechanisms underlying these gender differences.

The finding that the interaction between SMIs and OC is significant for women but not for men highlights the potential influence of factors such as social norms, social media usage, and prior investment experience. Barber and Odean (2001) suggest that men generally exhibit higher OC in investment decision-making. However, within the context of social media, women may be more susceptible to external influences like SMIs due to differences in information processing and social conformity.

Although this study focuses on Indonesian investors, its findings may be relevant to other emerging markets with similar digital and cultural characteristics. Indonesia’s high social media engagement, collectivist decision-making culture (Hofstede, 2011), and increasing retail investor participation may shape the impact of SMIs differently than in individualistic Western markets. In collectivist societies, the strong relationship between SMIs and OC may be more pronounced, as social validation plays a crucial role in shaping investor behavior (Nair & Shiva, 2023). However, key mechanisms, such as gender differences in the mediation of OC, are likely applicable to other markets with similar levels of SMIs penetration, such as India and Vietnam (Singh & Sarva, 2024).

This study contributes to understanding retail investor behavior in emerging markets by showing how OC and SMIs exposure differently affect AIB in men and women, highlighting the role of psychological and social factors in financial decisions. The findings carry practical implications for financial literacy education, especially for regulators and market authorities. Insights into cognitive biases amplified by social media can serve as a foundation for designing more targeted educational programs and fostering regulatory policies that enhance oversight of digital financial information, helping investors avoid harmful speculative behavior. Furthermore, the results also guide social media platforms and industry stakeholders in promoting transparency and ethical financial communication, especially among influencers.

Societal impact of the study

This study highlights how the growing influence of SMIs in Global South countries, particularly Indonesia, has significantly contributed to the rise of OC and AIB, particularly among female investors. Viral narratives promoted by so-called “finfluencers” have been shown to encourage speculative, impulsive, and high-risk investment decisions that are often not supported by adequate financial knowledge (Keasey et al., 2024; Wendy, 2024), This condition increases the likelihood of financial losses among novice investors, which not only diminish personal wealth but can also trigger broader household-level economic stress, thereby reinforcing existing social and economic vulnerabilities. The situation is further exacerbated by the generally low levels of financial and digital literacy in many developing countries, particularly among women, making them more prone to OC and vulnerable to AIB without a solid understanding of financial risks (Subran et al., 2023).

Weak regulatory oversight of financial content on social media has enabled the promotion of high-risk, non-transparent financial products. In many developing countries, limited consumer protection leaves novice investors-especially women prone to AIB-vulnerable to misleading information and unregulated financial advice (Kakhbod et al., 2023). This increases financial losses, widens socio-economic inequality, and erodes trust in formal financial systems. These dynamics hinder progress toward key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 8 (Inclusive Growth), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). Strengthening digital financial literacy is vital to promote financial literacy and sustainable development (Alqirem & Al-Smadi, 2025).

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study provide clear empirical evidence that overconfidence (OC) plays a significant mediating role in the relationship between social media influencers (SMIs) and aggressive investor behavior (AIB). This confirms that SMIs influence investor behavior not only directly but also indirectly by enhancing OC, which in turn drives aggressive investment tendencies. The results also demonstrate that SMIs have a significant impact on both OC and investor decision-making, further reinforcing their role as a key factor shaping individual investment behavior in the digital age.

Moreover, the study reveals that SMIs moderate the effect of OC on AIB, highlighting their role in amplifying risky decision-making among investors. Interestingly, this moderating effect shows a distinct gender pattern. The interaction between SMIs and OC was found to be significant for female investors, but not for male investors. Taken together, these results underscore the crucial role of SMIs and OC in shaping AIB, while also pointing to important gender-specific dynamics that should be considered in efforts to promote responsible investing and enhance financial literacy.

Understanding these dynamics is essential for policymakers, regulators, and financial practitioners in managing risks within the digital investment landscape. Recognizing the influence of OC and SMIs allows for the development of more effective strategies to promote rational decision-making and curb behaviors driven by excessive OC. For investors, exercising self-control is crucial to avoid unnecessary risks, while for regulators, enhancing financial literacy and implementing appropriate regulations for SMIs are key to protecting investment performance.

Building on these findings, future research could explore cross-cultural comparisons to examine how differences in financial literacy, regulatory environments, and social media usage influence SMIs-driven OC and AIB across various markets. Additionally, experimental studies could be designed to isolate platform-specific effects (e.g., TikTok vs. YouTube) to determine whether certain social media channels exacerbate behavioral biases more than others.

-

The reviewers did not authorize disclosure of their identity and peer review report.

-

Evaluated through a double-anonymized peer review. Associate Editor: Rodrigo Fernandes Malaquias

-

FUNDING

This study was conducted without financial support from any public, commercial, or non-profit funding agency.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive insights and professionalism throughout the review process.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Due to privacy and confidentiality agreements established during survey participation, the dataset cannot be shared publicly

REFERENCES

-

Abreu, M., & Mendes, V. (2012). Information, overconfidence and trading: Do the sources of information matter? Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(4), 868-881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2012.04.003

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2012.04.003 -

Adebambo, B. N., & Yan, X. (2018). Investor overconfidence, firm valuation, and corporate decisions. Management Science, 64(11), 5349-5369. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2806

» https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2806 -

Al-Shehri, M. (2021). Choosing the Best Social Media Influencer: The role of gender, age, and product type in influencer marketing. International Journal of Marketing Strategies, 4(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.47672/ijms.878

» https://doi.org/10.47672/ijms.878 -

AlFarraj, O., Alalwan, A. A., Obeidat, Z. M., Baabdullah, A., Aldmour, R., & Al-Haddad, S. (2021). Examining the impact of influencers’ credibility dimensions: attractiveness, trustworthiness and expertise on the purchase intention in the aesthetic dermatology industry. Review of International Business and Strategy, 31(3), 355-374. https://doi.org/10.1108/RIBS-07-2020-0089

» https://doi.org/10.1108/RIBS-07-2020-0089 -

Alqirem, R., & Al-Smadi, R. W. (2025). Enhancing Sustainable Fintech Education: Investigating the Role of Smartphones in Empowering Economic Development in Jordan. Discover Sustainability, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-025-01397-1

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-025-01397-1 -

Ambarwati, R., Kusuma, H., Arifin, Z., & Sutrisno. (2024). Exploration of the overconfidence behavior of millennial generation stock investors using the social network theory approach. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(9), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.24294/jipd.v8i9.5407

» https://doi.org/10.24294/jipd.v8i9.5407 -

Annick, T. S. (2020). Overconfidence and decision-making in Financial Markets [Universitast Pompen Fabra - Barcelona, Spain]. In Thesis https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429296918-17

» https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429296918-17 -

AnyMind. (2023). State of Influence in Asia 2022/2023 : A deep dive into the state of influencer marketing and the creator economy in Asia https://anymindgroup.com/vi/report/im-2223-report

» https://anymindgroup.com/vi/report/im-2223-report - Asogwa, C. E., Okeke, S. V, Gever, V. C., & Ezeah, G. (2020). Gender disparities in the influence of social media advertisements on buying decision in Nigeria. Communicatio: South African Journal of Communication Theory and Research, 46(3), 87-105.

-

Baker, H. K., Kumar, S., & Goyal, N. (2019). Personality traits and investor sentiment. Review of Behavioral Finance https://doi.org/10.1108/RBF-08-2017-0077

» https://doi.org/10.1108/RBF-08-2017-0077 -

Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2001). Boys will be boys: Gender, overconfidence, and common stock investment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 261-292. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355301556400

» https://doi.org/10.1162/003355301556400 -

Begum, R., & Siddiqui, D. A. (2024). Influence of Environmental , Governance and Reputational Factors on the Performance of Delegated Investments : Exploring the Mediating Role of Overconfidence Bias and Investment Decisions in. Business & Economic Review, 16(2), 1-58. https://doi.org/10.22547/BER/16.2.1

» https://doi.org/10.22547/BER/16.2.1 -

Biais, B., Glosten, L., & Spatt, C. (2005). Market microstructure: A survey of microfoundations, empirical results, and policy implications. Journal of Financial Markets, 8(2), 217-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.finmar.2004.11.001

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.finmar.2004.11.001 -

Bian, J., Chan, K., Shi, D., & Zhou, H. (2018). Do Behavioral Biases Affect Order Aggressiveness? Review of Finance, 22(3), 1121-1151. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfx037

» https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfx037 -

Chordia, T., Roll, R., & Subrahmanyam, A. (2001). Market liquidity and trading activity. Journal of Finance, 56(2), 501-530. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00335

» https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00335 -

Costa, D. F., Carvalho, F. de M., & Moreira, B. C. de M. (2019). Behavioral Economics and Behavioral Finance: a Bibliometric Analysis of the Scientific Fields. Journal of Economic Surveys, 33(1), 3-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12262

» https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12262 -

Foucault, T., Kadan, O., & Kandel, E. (2005). Limit order book as a market for liquidity. Review of Financial Studies, 18(4), 1171-1217. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhi029

» https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhi029 -

Ghani, M. T. A., Halim, B. A., Rahman, S. A. A., Abdullah, N. A., Afthanorhan, A., & Yaakub, N. (2023). Overconfidence Bias Among Investors: A Qualitative Evidence from Ponzi Scheme Case Study. Corporate and Business Strategy Review, 4(2), 59-75. https://doi.org/10.22495/cbsrv4i2art6

» https://doi.org/10.22495/cbsrv4i2art6 - Glosten, L. (1994). Electronic open limit order book. In The Journal of Finance (Vol. 49, Issue 4, pp. 1127-1161).

-

Guenther, P., Guenther, M., Ringle, C. M., Zaefarian, G., & Cartwright, S. (2023). Improving PLS-SEM use for business marketing research. Industrial Marketing Management, 111(March), 127-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2023.03.010

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2023.03.010 -

Haag, L., & Brahm, T. (2025). The Gender Gap in Economic and Financial Literacy: A Review and Research Agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 49(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.70031

» https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.70031 -

Haase, F., Rath, O., & Kurka, M. (2023). Finfluencers: Opinion Makers or Opinion Followers? Thirty-First European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS 2023), Kristiansand, Norway, 216. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2023_rp/216

» https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2023_rp/216 -

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2-24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

» https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203 - Harris, L. (2004). Trading and Exchanges: Market Microstructure for Practitioners (a review) (Vol. 60, Issue 4). ©2002 Oxford University Press.

-

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing Cultures : The Hofstede Model in Context Dimensionalizing Cultures : The Hofstede Model in Context Abstract. 2(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

» https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014 -

Hung, P. H., Chen, A. S., & Wu, Y. L. (2015). Order Aggressiveness, Price Impact, and Investment Performance in a Pure Order-Driven Stock Market. Asia-Pacific Journal of Financial Studies, 44(4), 635-660. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajfs.12102

» https://doi.org/10.1111/ajfs.12102 -

Inghelbrecht, K., & Tedde, M. (2024). Overconfidence, financial literacy and excessive trading. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 219, 152-195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2024.01.010

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2024.01.010 - Jamil, S. A., & Khan, K. (2016). Does gender difference impact investment decisions? Evidence from Oman. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 6(2), 456-460.

- Kakhbod, A., Kazempour, S., & Livdan, D. (2023). Finfluencer (23-30; Research Paper Series).

-

Keasey, K., Lambrinoudakis, C., Mascia, D. V., & Zhang, Z. (2024). The impact of social media influencers on the financial market performance of firms. European Financial Management, 745-785. https://doi.org/10.1111/eufm.12513

» https://doi.org/10.1111/eufm.12513 -

Khan, M. T. I., Tan, S. H., & Chong, L. L. (2019). Overconfidence Mediates How Perception of past Portfolio Returns Affects Investment Behaviors. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business, 20(2), 140-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/10599231.2019.1610688

» https://doi.org/10.1080/10599231.2019.1610688 -

Kyle, A. S. (1985). Continuous Auctions and Insider Trading. The Econometric Society, 53(6), 1315-1335. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1913210

» http://www.jstor.org/stable/1913210 -

Latif, K. F., Tariq, R., Muneeb, D., Sahibzada, U. F., & Ahmad, S. (2022). University Social Responsibility and performance: the role of service quality, reputation, student satisfaction and trust. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2022.2139791

» https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2022.2139791 -

Lawrence, E. R., Nguyen, T. D., & Wick, B. (2024). Gender difference in overconfidence and household financial literacy. Journal of Banking & Finance, 166, 107237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2024.107237

» https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2024.107237 -

Lei, M., & Lomax, R. G. (2005). The effect of varying degrees of nonnormality in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 12(1), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1201_1

» https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1201_1 -

Long, T. Q., & Tue, N. D. (2024). Financial Knowledge and Shortand Long-Term Financial Behavior Across Gender and Generations: Evidence from Japan. SAGE Open, 14(4), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241295846

» https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241295846 -

Mawad, J. L. J., & Freiha, S. S. (2024). The Role of Influencers in Shaping the Economic Decisions of Consumers Using the Logistic Regression Approach-Does the Generation Factor Matter? Sustainability (Switzerland), 16(21). https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219546

» https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219546 -

McCartney, M., Sullivan, F., & Heneghan, C. (2021). Information and rational decision-making: Explanations to patients and citizens about personal risk of COVID-19. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, 26(4), 143-146. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111541

» https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111541 -

Mishra, K. C., & Metilda, M. J. (2015). A study on the impact of investment experience, gender, and level of education on overconfidence and self-attribution bias. IIMB Management Review, 27(4), 228-239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iimb.2015.09.001

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iimb.2015.09.001 -

Mitchell, D., & Chen, J. (2020). Market or limit orders? Quantitative Finance, 20(3), 447-461. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697688.2019.1672882

» https://doi.org/10.1080/14697688.2019.1672882 -

Musnadi, S., Sofyan, S., Zuraida, Z., Rizal, M., & Agustina, M. (2025). Exploring overconfidence bias and demographic moderation in aggressive investor behavior; Evidence from Indonesia stock exchange (IDX). Contaduría y Administración, 70(2), 220-250. https://doi.org/10.22201/fca.24488410e.2025.5398

» https://doi.org/10.22201/fca.24488410e.2025.5398 -

Nair, P. S., & Shiva, A. (2023). Do social media interaction drive behavioral bias and trading tendencies of retail investors? A moderated-mediation approach. Journal of Content, Community and Communication, 17, 143-154. https://doi.org/10.31620/JCCC.09.23/12

» https://doi.org/10.31620/JCCC.09.23/12 -

O’Hara, M. (2015). High frequency market microstructure. Journal of Financial Economics, 116(2), 257-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2015.01.003

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2015.01.003 -

Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising, 19(3), 39-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673191

» https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673191 -

Pandey, I., & Guillemette, M. (2024). Social Media, Investment Knowledge, and Meme Stock Trading. Journal of Behavioral Finance https://doi.org/10.1080/15427560.2024.2361875

» https://doi.org/10.1080/15427560.2024.2361875 -

Parveen, S., Satti, Z. W., Subhan, Q. A., & Jamil, S. (2020). Exploring market overreaction, investors’ sentiments and investment decisions in an emerging stock market. Borsa Istanbul Review, 20(3), 224-235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2020.02.002

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2020.02.002 -

Rizal, M., Majid, M. S. A., Musnadi, S., & Sakir, A. (2024). Measuring aggressive decision-making behavior: A confirmatory factor analysis. International Journal of Applied Economics, Finance and Accounting, 18(1), 53-64. https://doi.org/10.33094/ijaefa.v18i1.1319

» https://doi.org/10.33094/ijaefa.v18i1.1319 -

Sathya, N., & Prabhavathi, C. (2024). The influence of social media on investment decision-making: examining behavioral biases, risk perception, and mediation effects. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 15(3), 957-963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13198-023-02182-x

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s13198-023-02182-x - Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2011). Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach (Fourth Ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

-

Sekścińska, K., Jaworska, D., Rudzinska-Wojciechowska, J., & Kusev, P. (2023). The Effects of Activating Gender-Related Social Roles on Financial Risk-Taking. Experimental Psychology, 70(1), 40-50. https://doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169/a000576

» https://doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169/a000576 -

Shiller, R. (2003). From Efficient Markets Theory to Behavioral Finance. Journal OfEconomic Perspectives, 17(1), 83-104. https://doi.org/10.5937/megrev1402073k

» https://doi.org/10.5937/megrev1402073k - Singh, S., & Sarva, M. (2024). The Rise of Finfluencers : A Digital Transformation in Investment Advice. 18(3), 269-286.

-

Sood, D., & Sharma, V. K. (2022). Behavioural Biases in Investor’s Stock Market Participation in Post Pandemic Phase: A Literature Review Approach. ECS Transactions, 107(1), 10585. https://doi.org/10.1149/10701.10585ecst

» https://doi.org/10.1149/10701.10585ecst - Stoll, H. R. (2002). Market Microstructure. In Handbook of Economics of Finance (Financial Markets Research Center Working paper Nr. 01-16; Vol. 3).

-

Subran, L., Romero, P. P., Holzhausen, A., & Carrera, J. B. (2023). Playing With a Squared Ball: The Financial Literacy Gender GAP. Allianz Research, July https://www.allianz.com/en/economic_research/insights/publications/specials_fmo/financial-literacy.html

» https://www.allianz.com/en/economic_research/insights/publications/specials_fmo/financial-literacy.html -

Tripathi, A., Vipul, V., & Dixit, A. (2020). Limit order books: a systematic review of literature. In Qualitative Research in Financial Markets (Vol. 12, Issue 4, pp. 505-541). Emerald Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRFM-07-2019-0080

» https://doi.org/10.1108/QRFM-07-2019-0080 -

Walczak, D., & Sylwia, P. K. (2018). Gender differences in financial behaviours. Engineering Economics, 29(1), 123-132. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.29.1.16400

» https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.29.1.16400 -

Wendy, W. (2024). The nexus between financial literacy, risk perception and investment decisions: Evidence from Indonesian investors. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 21(3), 135-147. https://doi.org/10.21511/imfi.21(3).2024.12

» https://doi.org/10.21511/imfi.21(3).2024.12 -

Werner, F. M., Bondt, D., & Thaler, R. (1985). Does the Stock Market Overreact? The Journal of Finance, 40(3), 793-805. https://doi.org/10.2307/2327804

» https://doi.org/10.2307/2327804 -

X. H. Bao, H., & Li, S. H. (2020). Investor Overconfidence and Trading Activity in the Asia Pacific REIT Markets. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13100232

» https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13100232

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

28 Nov 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

27 Nov 2024 -

Accepted

05 Aug 2025

AGGRESSIVE INVESTOR BEHAVIOR IN THE ERA OF SOCIAL MEDIA: A GENDERED PERSPECTIVE

AGGRESSIVE INVESTOR BEHAVIOR IN THE ERA OF SOCIAL MEDIA: A GENDERED PERSPECTIVE