Objective: to map the scientific literature regarding the use of the Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score in hospitalized adults.

Method: scoping review, structured according to the methodological guidelines of the Joanna Briggs Institute - Evidence Synthesis Groups, with searches in seven databases and gray literature. The studies were selected by two reviewers, using an instrument for data extraction.

Results: the analysis of the 29 selected studies showed a predominance of longitudinal studies (34.48%), conducted in Brazil (48.27%) in Intensive Care Units (29%), and published between 2020 and 2021 (48.24%). The studies demonstrated the use of the Perme Score for description and reliability of the instrument, translation and cultural adaptation, association between functional mobility, clinical characteristics and outcomes, mobility assessment after interventions, mobility assessment and potential barriers to mobilization, and use of the score for validation of other instruments and various clinical profiles.

Conclusion: the Perme Score is an instrument capable of measuring physical mobility, including possible barriers to mobility, with potential for use in scenarios outside the Intensive Care Unit, in intervention studies for early mobilization and prediction of hospitalization outcomes.

Descriptors:

Mobility Limitation; Early Ambulation; Physical Therapy Modalities; Inpatients; Rehabilitation Nursing; Review

Highlights:

(1) The Perme Score demonstrates great potential for use in various settings. (2) Studies position nurses within the context of functional mobility assessment. (3) The Perme Score has been employed in intervention protocols for early mobility.

Objetivo: mapear a literatura científica referente ao uso do Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score em indivíduos adultos hospitalizados.

Método: revisão de escopo, estruturada nas diretrizes metodológicas do Joanna Briggs Institute - Evidence Synthesis Groups, com buscas em sete bases de dados e literatura cinzenta. Os estudos foram selecionados por dois revisores, utilizando um instrumento para a extração dos dados.

Resultados: a análise dos 29 estudos selecionados mostrou predomínio de estudos longitudinais (34,48%), realizados no Brasil (48,27%) em Unidades de Terapia Intensiva (29%), e publicados entre 2020 e 2021 (48,24%). Os estudos evidenciaram a utilização do Perme Score para descrição e confiabilidade do instrumento, tradução e adaptação cultural, associação entre mobilidade funcional, características clínicas e desfechos, avaliação da mobilidade após intervenções, avaliação da mobilidade e potenciais barreiras para a mobilização, e uso da pontuação para validação de outros instrumentos e perfis clínicos diversos.

Conclusão: o Perme Score é um instrumento que permite mensurar a mobilidade física, incluindo as possíveis barreiras à mobilidade, com potencial para utilização em cenários externos à Unidade de Terapia Intensiva, em estudos de intervenção para mobilização precoce e predição de desfechos da hospitalização.

Descritores:

Limitação da Mobilidade; Deambulação Precoce; Modalidades de Fisioterapia; Pacientes Internados; Enfermagem em Reabilitação; Revisão

Destaques:

(1) O Perme Score apresenta grande potencial de uso em diferentes cenários. (2) Estudos posicionam o enfermeiro no contexto da avaliação da mobilidade funcional. (3) O Perme Score tem sido empregado em protocolos de intervenção para mobilidade precoce.

Objetivo: mapear la literatura científica referente al uso del Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score en individuos adultos hospitalizados.

Método: revisión de alcance, estructurada según las directrices metodológicas del Joanna Briggs Institute - Evidence Synthesis Groups, con búsquedas en siete bases de datos y literatura gris. Los estudios fueron seleccionados por dos revisores, utilizando un instrumento para la extracción de datos.

Resultados: el análisis de los 29 estudios seleccionados mostró un predominio de estudios longitudinales (34,48%), realizados en Brasil (48,27%) en Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos (29%) y publicados entre 2020 y 2021 (48,24%). Los estudios evidenciaron el uso del Perme Score para la descripción y confiabilidad del instrumento, traducción y adaptación cultural, asociación entre la movilidad funcional, características clínicas y resultados, evaluación de la movilidad tras intervenciones, evaluación de la movilidad y potenciales barreras para la movilización, además del uso de la puntuación para la validación de otros instrumentos y perfiles clínicos diversos.

Conclusión: el Perme Score es un instrumento capaz de medir la movilidad física, incluyendo posibles barreras para la movilidad, con potencial para su uso en escenarios fuera de la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos, en estudios de intervención para movilización temprana y predicción de resultados de la hospitalización.

Descriptores:

Limitación de la Movilidad; Ambulación Precoz; Modalidades de Fisioterapia; Pacientes Internos; Enfermería en Rehabilitación; Revisión

Destacados:

(1) El Perme Score presenta un gran potencial de uso en diferentes escenarios. (2) Estudios posicionan al enfermero en el contexto de la evaluación de la movilidad funcional. (3) El Perme Score se ha empleado en protocolos de intervención para la movilización temprana.

Introduction

The hospital institution is considered a space that provides symptom relief, health recovery, and access to diagnosis. However, depending on the care and treatments provided, as well as other factors, hospitalization can become a disruptive factor, leading to greater clinical and functional deterioration, increased length of stay, decompensation of multimorbidities, and higher risk of mortality ( 1 ).

The consequences of mobility decline during hospitalization can extend for up to five years after discharge, resulting from prolonged hospitalizations associated with age, disease severity, and type of admission (acute/elective). These were the conclusions of a cohort study conducted with 10,430 individuals, in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) group (n= 5,215) and in the general ward group (n= 5,215), with a median age of 60 years (range 44–72) in Edinburgh (United Kingdom). The ICU group showed an association with higher mortality (RR 1.33; 95% CI, 1.22–1.46, p=0.001), higher costs ($25,608 vs. $16,913/patient1), and longer hospital stay (51%) ( 2 ).

It is estimated that hospitalization is associated with a 30% physical deconditioning ( 3 ). Therefore, functional decline is not only related to the clinical condition that led to hospitalization, and recovery is not automatic after the resolution of the issue that caused it ( 4 ). It is important to note that functional mobility is a predictor of health. Thus, assessing locomotor functions in the hospital context and understanding the barriers to early mobilization become essential.

Early mobilization should be understood as part of the rehabilitation process of hospitalized patients, especially in the ICU, minimizing muscle weakness and worsening of physical function ( 5 ). There are several scales that assess functional aspects in the ICU, such as the Physical Function in Intensive care Test scored, Chelsea Critical Care Physical Assessment tool, Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score, Surgical intensive care unit Optimal Mobilization Score, ICU Mobility Scale and Functional Status Score for the ICU ( 6 ). None of them have been considered the “gold standard” for quantifying functional mobility, while also being quick and objective to apply. However, the Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score takes into account extrinsic conditions affecting the patient’s mobility in bed, such as the presence of access lines, tubes and chest drains, which can be interpreted as barriers to mobility. The presence of these devices is not scored or considered in most scales.

The Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score, created by Christiane Strambi Perme and here referred to as the Perme Score, was translated and adapted into Portuguese. It consists of seven categories that assess mental state, potential barriers to mobility, functional strength, bed mobility, transfers, assistive devices for ambulation, and resistance measures. The score ranges from 0 to 32 points; a higher score indicates greater mobility and less need for assistance, while a lower score indicates lower mobility and greater need for assistance ( 7 ).

Despite being a relatively new instrument, already translated into different languages, and introducing the innovation of assessing potential barriers to mobility in the ICU, it is essential to represent publications on the score in the literature, considering different clinical conditions and settings. After a preliminary search in public databases of review protocol registrations and online databases, and in the absence of systematic reviews or protocol records on this scale, the development of this review was deemed essential. The aim was to map the scientific literature regarding the use of the Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score in hospitalized adults.

Method

Type of study

This is a scoping review, a systematic method that identifies and synthesizes knowledge through existing or emerging literature, maps the extent and scope of the topic, the nature of the literature, and identifies potential gaps ( 8 ). The review was developed according to the recommendations of the JBI – Evidence Synthesis Groups, a method recommended for scoping reviews ( 9 ), in addition to the guidelines set by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR), and was registered in the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (INPLASY), under number 2023100031 (https://inplasy.com/inplasy-2023-10-0031).

Thus, the scoping review was operationalized in five stages: 1- establishment of the research question; 2- identification of relevant studies; 3- selection and inclusion of studies; 4- data organization; and 5- collection, synthesis and reporting of results ( 10 - 11 ). The question and the main search elements for this review were developed using the PCC strategy (P – Population or Patients; C – Concept; C – Context) ( 12 ), with P (adult individuals), C (Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score), and C (hospital). In Context, hospital environment refers to any care sector within the hospital unit.

Therefore, the following question was formulated: what is the available evidence in the literature regarding the use of the Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score in hospitalized adults?

Selection criteria

Regarding the eligibility of the studies, the inclusion criteria were: (1) to be primary and secondary empirical research, both quantitative and qualitative, of any design or methodology; (2) to include the variables of interest “Perme Score” and “hospitalization”; (3) to be published in English, Spanish, Portuguese or French; (4) to have been published since 2014, the year the scale was published. The exclusion criteria for the studies were: letters to the editor, abstracts in conference proceedings, dissertations, theses, monographs, and case reports that did not present the variable of interest of the research.

Data search and collection

Initially, the search strategy was developed based on the identification of the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) descriptors: mobility limitation, early ambulation, physical therapy modalities, and inpatients, associated with the free term “Perme”. These descriptors were then translated into the specific terms for each database searched, such as the Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) and the Embase Subject Headings (Emtree).

However, the databases and portals tended to zero when the descriptors were combined using the Boolean operator “AND”. Consequently, assistance from a professional librarian was sought to minimize the possibility of errors. Thus, the search strategy was redefined to include only the free terms: “Perme” OR “Perme scale” OR “Perme score”.

In October 2023, searches were conducted in the following databases: Virtual Health Library, EMBASE, PEDro, PubMed, SciELO, Scopus and Web of Science. The titles and abstracts of the articles were sent to two reviewers, who independently assessed their eligibility. For gray literature, the search was conducted in the Catalog of Theses and Dissertations of the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES). Among the gray literature studies that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, all already had articles published in journals, which were included in the review.

The results of the textual searches were exported and transferred to the free reference manager Mendeley, a tool that allows access by multiple researchers and organizes references into separate folders. Duplicates were removed, keeping only one of the titles. Subsequently, the titles and abstracts were reviewed, and articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria or contained any exclusion criteria were eliminated. Finally, the selected texts were made available to the reviewers for full reading, completing the inclusion process.

The researchers, responsible for the review, are professionals with expertise in gerontology and members of a Multidisciplinary Research Group on the Elderly.

It is worth noting that the Kappa concordance coefficient was used to describe the degree of agreement between the reviewers, which is based on the number of concordant responses, i.e., the frequency with which the results coincide between reviewers ( 13 ). In this study, the overall agreement among reviewers was 96.81%, corresponding to a Kappa coefficient higher than 0.90. Furthermore, a third reviewer assessed the discrepancies in study selection to make the final decision on inclusion or exclusion, aiming to minimize the risk of bias.

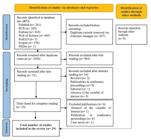

The number of articles found in each database and the sum of all databases were recorded in the PRISMA flow diagram ( 14 ), as well as the selection process and reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and analysis

The extraction and descriptive analysis of the data were conducted using a protocol developed by the authors themselves, which encompasses the previously defined eligibility criteria, as widely recommended by the JBI. In this context, the following information was included: author’s name and year of publication, journal, country of origin, objectives, results, study design and sample size.

Due to the chosen method, there was no need for a formal assessment of the methodological quality of the included studies. However, adherence to the evaluation items of the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist aimed to ensure the methodological rigor of the content ( 15 ). Finally, a thematic analysis of the content was conducted to identify the converging points in the literature, outline the strengths of the topic, and highlight existing gaps.

Ethical aspects

Since the studies used are in the public domain, there was no need for submission to the Research Ethics Committee, according to Resolution CNS n° 510, of 2016.

Results

The search in the portals and databases resulted in 1,873 studies. Of these, 837 were excluded as duplicates, using the free reference manager Mendeley. After removing the duplicates, the 1,036 articles selected for title and abstract reading were organized in an Excel spreadsheet for further analysis. Subsequently, 985 articles were excluded after reading the titles, and 16 after reading the abstracts, resulting in 35 studies for full-text review. Of these, six were excluded, totaling 29 studies for review. To minimize the possible risk of bias in the selection of studies, the reviewers organized the references in the free reference manager Mendeley. The refinement was conducted by two independent evaluators aiming for 100% agreement. A third reviewer assessed any potential discrepancies in the selection of studies to make the final decision on inclusion or exclusion. These procedures are represented in Figure 1, in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram, which illustrates the article selection process for this review ( 14 ).

In Figure 2, the methodological design, the study focus, the study locations, and the clinical profiles, which are the main findings, are observed.

Schematic representation of the findings of studies involving the Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score. Curitiba, PR, Brazil, 2024

In Figure 3, the articles are categorized by author/year of publication, journal, country of origin, objectives, results, study design, and sample size.

Among the studies analyzed, most publications were from 2021 (n= 8; 27.58%), followed by 2020 (n= 7; 24.14%), 2022 and 2023 (n= 3; 10.34% each year), 2014, 2018 and 2019 (n= 2; 6.9% each year), and finally, 2016 and 2017 (n= 1; 3.45% each year).

Regarding the journals, 25 different ones were identified, with a predominance of Colombia Médica, NeuroRehabilitation, PloS One and Revista Brasileira de Terapia Intensiva (n= 2; 6.89% each). The countries that stood out as host of the studies were: Brazil (n= 14; 48.27%), United States of America (n= 6; 20.68%), Colombia (n= 3; 10.35%), India and Turkey (n= 2; 6.9% each), in addition to Germany and Taiwan (n= 1; 3.45% each). All articles (n= 29) were published in English.

Regarding the methodological design, longitudinal studies predominated (n= 10; 34.48%). The others were methodological studies (n= 8; 27.58%), retrospective cohort studies (n= 4; 13.79%), cross-sectional studies (n= 3; 10.35%), interventional studies (n= 2; 6.9%), randomized clinical trial and non-randomized clinical trial (n= 1; 3.45% each). A total of 3,399 participants were observed in the studies, with sizes ranging from 18 to 949 participants.

The studies addressed a variety of topics, such as description and reliability of the instrument designed by Christiane Strambi Perme ( 16 - 17 ); translation and cultural adaptation into other languages ( 5 , 18 - 19 ); association between functional mobility and clinical characteristics ( 20 ); assessment of mobility and patient outcomes ( 21 - 25 , 30 ); assessment of mobility following specific interventions, such as the early mobilization protocol ( 26 ), comparison between conventional physiotherapy and cycle ergometer ( 27 - 28 ); assessment of mobility and potential barriers to mobilization ( 29 - 30 ) and the use of the Perme Score as a validation tool for other instruments ( 31 - 33 ).

Most of the studies were conducted primarily in the ICU. Only two studies were carried out in hospital inpatient units (wards) ( 24 , 36 ). Another relevant detail concerns the specific profiles of the patients monitored, which included cases of COVID-19 ( 24 , 34 - 35 ), liver transplantation ( 36 ), cardiac surgery ( 37 ), tracheostomized ( 38 ) and organophosphate poisoning ( 29 ).

Discussion

The Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score was developed to assess functional mobility and comprises the following subcategories: mental status, potential barriers to mobility, functional strength, bed mobility, transfers, gait and endurance. The instrument demonstrated an agreement of 94.29% (68.57%-100%) between evaluators ( 16 ), with its reliability evaluated in a cardiovascular ICU in the same year ( 17 ).

After assessing the reliability of the instrument, it was translated and validated into Brazilian Portuguese ( 5 ), Spanish ( 19 ) and German ( 18 ), which, in addition to the translation and cross-cultural validation, obtained inter-rater reliability (physiotherapists and nurses) of 96% (93-97%), highlighting the role of the nursing professional in the context of functional mobility assessment ( 18 ).

Regarding publications on the Perme Score, the first studies described the instrument. Later, studies focused on specific clinical conditions, postoperative complications and clinical outcomes. Higher Perme Score values were associated with hospital discharge to home ( 21 ).

Different Perme Score values guide discharge referrals. Patients discharged to home had a Perme Score of 29; to home care, 12; to rehabilitation hospitals, 26; to specialized nursing services, 13; and for death, 7 ( 21 ). A similar discharge profile was observed in patients admitted to ICUs in the United States of America: home 26.05 (±5.42), long-term care institutions 18.65 (±8.43), specialized nursing services 17.38 (±7.72), and rehabilitation 20.3 (±7.48) ( 41 ). In this context, the Perme Score proves to be a useful tool for assessing the effectiveness of in-hospital rehabilitation, guiding efforts for the appropriate referral of patients within the Healthcare Network (HCN) to enhance mobility and, consequently, achieve better outcomes.

The Perme Score for the death outcome was lower (0.57; ±1.98) when compared to the score at hospital discharge (7.27; ±8.16), p< 0.0001, and the use of vasoactive drugs and sedatives was higher in the death group, p≤ 0.0001. In addition, clinical hospitalizations had a lower Perme Score than surgical hospitalizations (4.15 ±7.30 vs. 5.44±6.75, p< 0.01) ( 40 ). Considering that immobility is associated with a series of negative outcomes, mobility assessment, as well as the implementation of an early mobilization program, should be incorporated in care management.

Although most studies applied the Perme Score in the ICU, some utilized it in Inpatient Units (IU). An average increase in functional mobility was observed in the IU (7.3; 95% CI 5.7-8.8, p< 0.001) between admission and hospital discharge. The mean Perme Score values at IU admission were 17.5 (95% CI 15.8–19.3), and at hospital discharge 24.8 (95%CI 23.3-26.3) ( 24 ). These studies extend the use of the Perme Score beyond the ICU, demonstrating the feasibility of applying the tool to manage mobility in different healthcare settings.

The use of early mobilization protocols to improve the functional mobility status of ICU patients contributes to a significant increase in the Perme Score from the first day of admission to the last day of rehabilitation ( 26 ). Early ambulation interventions were also studied, showing that patients who ambulated early experienced a smaller decrease in the Perme Score after cardiac valve surgery ( 37 ). Additionally, early mobilization demonstrated better outcomes in the functional mobility of patients with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI). The Intervention Group (IG) showed a significant increase in the Perme Score at ICU discharge compared to the Control Group (CG) (IG 6.62 ± 4.33 vs. CG 3.64 ± 1.66, p= 0.001) ( 39 ).

In the same context, the use of a cycle ergometer in rehabilitation after acute cerebrovascular accident demonstrated greater mobility and functionality in relation to conventional physiotherapy ( 27 ). Early mobilization should prioritize social reintegration to minimize or reverse the impacts of hospitalization through activities that promote independence. Therefore, early mobilization should be a goal for the entire multidisciplinary team.

Potential barriers to mobilization should be assessed by the multidisciplinary team and, once identified, strategies can be developed to minimize them. Higher scores on Potential Barriers to Mobilization were associated with higher Perme Score values, shorter length of stay on mechanical ventilation and shorter total length of stay in the ICU ( 30 ).

A study conducted in the USA aimed to assess the mobility and self-care of elderly patients in the ICU and identify barriers to early mobilization. An initial Perme Score of 23 (IQR 11.5-28) and a final score of 27 (IQR 16-31) were observed, with 76% of patients showing improvement. The reasons for the lack of early mobilization included insufficient staff or time (17%), cognitive inability to follow instructions (8%), sedation (6%), hemodynamic instability (3%), and transition to comfort care/hospice (3%) ( 43 ).

The Perme Score demonstrated predictive power in the postoperative period of liver transplantation, showing an inverse association between the score and the duration of mechanical ventilation (p= 0.042), as well as the number of physiotherapy interventions in the inpatient unit (p= 0.001) ( 36 ).

Functional mobility performance was evidenced after the use of the speaking valve in tracheostomized individuals, with the Perme Score increasing from 11.3 (IQR 10.1-12.0) to 18.2 (IQR 16.2-20.1); p< 0.01. The benefits of the speaking valve are widely discussed in relation to speech processes and adjustments to more physiological respiratory patterns, as well as swallowing processes. However, the indirect benefits of the speaking valve are less frequently addressed. When initiated shortly after the cessation of mechanical ventilation in tracheostomized individuals, it can improve mobility capacity ( 38 ).

The Perme Score was used as a comparative parameter in the translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Functional Status Score for the Intensive Care Unit (FSS-ICU) ( 31 ) and the ICU mobility scale (IMS) into Turkish ( 32 ). The validation of the Perme Score for Turkish was not included in this review, as the study has not been published and is only available in the dissertation database of Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University , written in Turkish. In addition to these studies, the Perme Score was also employed in the translation of the Early Rehabilitation Index (ERI) into Brazilian Portuguese ( 33 ). Due to its ease of application and consideration of potential mobility barriers, it has been used as a comparative index for new instruments.

It is important to note that no additional tests for the validation of psychometric properties and construct validity were found in the literature. Although not mandatory, it is highly recommended that, after the translation and adaptation process, researchers ensure that the new version demonstrates the necessary measurement properties for the intended application. This would provide greater confidence that the adapted instrument measures a construct comparable to the original ( 44 ).

A limitation of this study is the absence of psychometric validation of the scale. Furthermore, the chosen method aims to map the literature in a specific field of interest rather than identify the best evidence for a health intervention. Therefore, it was not possible to classify the robustness of the evidence, only to track it and anticipate its potential. Despite these limitations, a strong point of this review is the comprehensive search strategy and the standardized data extraction process required by the JBI. Further studies are suggested to conduct additional tests of the version adapted to Brazilian Portuguese, facilitating the use of the scale in settings beyond the ICU, as has already been demonstrated.

As a contribution to scientific knowledge in the health field, the possibility of using the Perme Score in other hospital sectors stands out, assisting in the rapid and objective measurement of functional mobility, including considering extrinsic conditions to the patient.

Conclusion

This scoping review mapped the application of the Perme Score in the description and assessment of the instrument’s reliability, as well as its use as a reference for the translation and cultural adaptation of other instruments. Additionally, it addressed the assessment of functional mobility in association with clinical characteristics, clinical outcomes, and potential barriers to mobility. The review also highlighted the use of the Perme Score in intervention protocols for early mobilization, the assessment of functional mobility during conventional physiotherapy, and the use of the cycle ergometer.

The different scores on the functional mobility scale were associated with clinical characteristics and their outcomes, interventions, and potential mobility barriers.

Although the Perme Score was initially developed for assessing functional mobility in ICU, it has demonstrated great potential for use in different contexts. It is an instrument that allows functional mobility to be measured quickly, objectively and specifically, while also considering factors external to the patient.

References

-

1. Warner JL, Zhang P, Liu J, Alterovitz G. Classification of hospital acquired complications using temporal clinical information from a large electronic health record. J Biomed Inform. 2016;59:209-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2015.12.008

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2015.12.008 -

2. Lone NI, Gillies MA, Haddow C, Dobbie R, Rowan KM, Wild SH, et al. Five-Year Mortality and Hospital Costs Associated with Surviving Intensive Care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(2):198-208. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201511-2234OC

» https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201511-2234OC -

3. Loyd C, Markland AD, Zhang Y, Fowler M, Harper S, Wright NC, et al. Prevalence of Hospital-Associated Disability in Older Adults: A Meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(4):455-461.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.09.015

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.09.015 -

4. Palese A, Gonella S, Moreale R, Guarnier A, Barelli P, Zambiasi P, et al. Hospital-acquired functional decline in older patients cared for in acute medical wards and predictors: Findings from a multicentre longitudinal study. Geriatr Nurs. 2016;37(3):192-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.01.001

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.01.001 -

5. Aquim EE, Bernardo WM, Buzzini RF, Azeredo NSG, Cunha LS, Damasceno MCP, et al. Brazilian Guidelines for Early Mobilization in Intensive Care Unit. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2019;31(4):434-43. https://doi.org/10.5935/0103-507X.20190084

» https://doi.org/10.5935/0103-507X.20190084 -

6. Parry SM, Denehy L, Beach LJ, Berney S, Williamson HC, Granger CL. Functional outcomes in ICU – what should we be using? - an observational study. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):127. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-0829-5

» https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-0829-5 -

7. Kawaguchi YMF, Nawa RK, Figueiredo TB, Martins L, Pires-Neto RC. Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score and ICU Mobility Scale: translation into Portuguese and cross-cultural adaptation for use in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2016;42(6):429-34. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37562015000000301

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37562015000000301 -

8. Mak S, Thomas A. Steps for Conducting a Scoping Review. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(5):565-7. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-22-00621.1

» https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-22-00621.1 -

9. Peters MD, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla B, Jordan Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Adelaide: JBI; 2024. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-24-09

» https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-24-09 -

10. Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141-6. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

» https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 -

11. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

» https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616 -

12. Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371-85. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

» https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123 - 13. Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, Grady DG, Newman TB. Designing clinical research. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2013. 367 p.

-

14. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

» https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71 -

15. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467-73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-085

» https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-085 -

16. Perme C, Nawa RK, Winkelman C, Masud F. A Tool to Assess Mobility Status in Critically Ill Patients: The Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;10(1):41-9. https://doi.org/10.14797/mdcj-10-1-41

» https://doi.org/10.14797/mdcj-10-1-41 -

17. Nawa RK, Lettvin C, Winkelman C, Evora PRB, Perme C. Initial interrater reliability for a novel measure of patient mobility in a cardiovascular intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2014;29(3):475.e1-475.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.01.019

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.01.019 -

18. Nydahl P, Wilkens S, Glase S, Mohr LM, Richter P, Klarmann S, et al. The German translation of the Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score and inter-rater reliability between physiotherapists and nurses. Eur J Physiother. 2018;20(2):109-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/21679169.2017.1401660

» https://doi.org/10.1080/21679169.2017.1401660 -

19. Wilches Luna EC, Hernández NL, Oliveira AS, Nawa RK, Perme C, Gastaldi AC. Perme ICU Mobility Score (Perme Score) and the ICU Mobility Scale (IMS): translation and cultural adaptation for the Spanish language. Colomb Med (Cali). 2018;49(4):265-72. https://doi.org/10.25100/cm.v49i4.4042

» https://doi.org/10.25100/cm.v49i4.4042 -

20. Nawa RK, Santos TD, Real AA, Matheus SC, Ximenes MT, Cardoso DM, et al. Relationship between Perme ICU Mobility Score and length of stay in patients after cardiac surgery. Colomb Med (Cali). 2022;53(3):e2005179. https://doi.org/10.25100/cm.v53i3.5179

» https://doi.org/10.25100/cm.v53i3.5179 -

21. Yang DH, Weinreich M, Dickason S, Herman J, Brown J, Leveno M. Functional mobility scores and discharge disposition in the parkland mICU: A descriptive study. In: American Thoracic Society 2017 International Conference [Internet]; 2017 May 19-24; Washington, D.C. New York, NY: American Thoracic Society; 2017 [cited 2024 Apr 26]. (American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care, vol. 195). Available from: https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2017.195.1_MeetingAbstracts.A1766?download=true

» https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2017.195.1_MeetingAbstracts.A1766?download=true -

22. Moecke DMP, Biscaro RRM. Functional status analysis of critically ill patients in the intensive care unit. Fisioter Bras. 2019;20(1):17-26. https://doi.org/10.33233/fb.v20i1.2143

» https://doi.org/10.33233/fb.v20i1.2143 -

23. Lima EA, Rodrigues G, Peixoto AA Júnior, Sena RS, Viana SMNR, Mont’Alverne DGB. Mobility and clinical outcome of patients admitted to an intensive care unit. Fisioter Mov. 2020;33:e003368. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-5918.032.AO67

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-5918.032.AO67 -

24. Nascimento MS, Talerman C, Eid RAC, Brandi S, Gentil LLS, Semeraro FM, et al. Application of the Perme Score to assess mobility in patients with COVID-19 in inpatient units. Can J Respir Ther. 2023;59:167-74. https://doi.org/10.29390/001c.84263

» https://doi.org/10.29390/001c.84263 -

25. Tavares GS, Oliveira CC, Mendes LPS, Velloso M. Muscle strength and mobility of individuals with COVID-19 compared with non-COVID-19 in intensive care. Heart Lung. 2023;62:233-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2023.08.004

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2023.08.004 -

26. Gatty A, Samuel SR, Alaparthi GK, Prabhu D, Upadya M, Krishnan S, et al. Effectiveness of structured early mobilization protocol on mobility status of patients in medical intensive care unit. Physiother Theory Pract. 2022;38(10):1345-57. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2020.1840683

» https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2020.1840683 -

27. Pinheiro DRR, Cabeleira MEP, Campo LA, Corrêa PS, Blauth AHEG, Cechetti F. Effects of aerobic cycling training on mobility and functionality of acute stroke subjects: A randomized clinical trial. NeuroRehabilitation. 2021;48(1):39-47. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-201585

» https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-201585 -

28. De Souza RCD, De Andrade NP, De Carvalho EM, Melo FG. Protein, caloric and anthropometric analysis of patients submitted to conventional physiotherapy and cycle ergometer of inferior members in ICU: a pilot study. Rev Pesq Fisio. 2021;11(4):631-9. https://doi.org/10.17267/2238-2704rpf.v11i4.3839

» https://doi.org/10.17267/2238-2704rpf.v11i4.3839 -

29. Pinto VC, Bairapareddy KC, Prabhu N, Alaparthi GK, Chandrasekaran B, Vaishali K, et al. Recovery Pattern and Barriers to Mobilization during Acute Rehabilitation Phase in Organophosphate Poisoning Patients. Crit Rev Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;32(3):193-203. https://doi.org/10.1615/CritRevPhysRehabilMed.2020035377

» https://doi.org/10.1615/CritRevPhysRehabilMed.2020035377 -

30. Luna ECW, Perme C, Gastaldi AC. Relationship between potential barriers to early mobilization in adult patients during intensive care stay using the Perme ICU Mobility score. Can J Respir Ther. 2021;57:148-53. https://doi.org/10.29390/cjrt-2021-018

» https://doi.org/10.29390/cjrt-2021-018 -

31. Kahraman BO, Ozsoy I, Kahraman T, Tanriverdi A, Acar S, Ozpelit E, et al. Turkish translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and assessment of psychometric properties of the Functional Status Score for the Intensive Care Unit. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(21):3092-7. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1602852

» https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1602852 -

32. Özsoy İ, Kahraman BO, Kahraman T, Tanriverdi̇ A, Acar S, Özpeli̇ E, et al. Assessment of psychometric properties, cross-cultural adaptation, and translation of the Turkish version of the ICU mobility scale. Turk J Med Sci. 2021;51(3):1153-7. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-2005-319

» https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-2005-319 -

33. Reis NFD, Biscaro RRM, Figueiredo FCXS, Lunardelli ECB, Silva RMD. Early Rehabilitation Index: translation and crosscultural adaptation to Brazilian Portuguese; and Early Rehabilitation Barthel Index: validation for use in the intensive care unit. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2021;33(3): 353-61. https://doi.org/10.5935/0103-507X.20210051

» https://doi.org/10.5935/0103-507X.20210051 -

34. Timenetsky KT, Serpa A Neto, Lazarin AC, Pardini A, Moreira CRS, Corrêa TD, et al. The Perme Mobility Index: A new concept to assess mobility level in patients with coronavirus (COVID-19) infection. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0250180. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250180

» https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250180 -

35. Nawa RK, Serpa A Neto, Lazarin AC, Silva AK, Nascimento C, Midega TD, et al. Analysis of mobility level of COVID-19 patients undergoing mechanical ventilation support: A single center, retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0272373. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272373

» https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272373 -

36. Pereira CS, Carvalho ATD, Bosco AD, Forgiarini LA Júnior. The Perme scale score as a predictor of functional status and complications after discharge from the intensive care unit in patients undergoing liver transplantation. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2019;31(1):57-62. https://doi.org/10.5935/0103-507X.20190016

» https://doi.org/10.5935/0103-507X.20190016 -

37. Cordeiro ALL, Reis JRD, Cruz HBD, Guimarães AR, Gardenghi G. Impact of early ambulation on functionality in patients undergoing valve replacement surgery. J Clin Transl Res [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Apr 3];7(6):754-8. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8710356/pdf/jclintranslres-2021-7-6-754.pdf

» https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8710356/pdf/jclintranslres-2021-7-6-754.pdf -

38. Ceron C, Otto D, Signorini AV, Beck MC, Camilis M, Sganzerla D, et al. The Effect of Speaking Valves on ICU Mobility of Individuals With Tracheostomy. Respir Care. 2020;65(2):144-9. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.06768

» https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.06768 -

39. Yen HC, Han YY, Hsiao WL, Hsu PM, Pan GS, Li MH, et al. Functional mobility effects of progressive early mobilization protocol on people with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury: A pre-post intervention study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2022;51(2):303-13. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-220023

» https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-220023 -

40. Cavalli ACZ, Schoeller SD, Chesani FH, Vargas CP, Almeida CAM, Vargas MAO, et al. Score of Perme: Analysis of Clinical Destroys the High or Death the Intensive Care Unit. Middle East J Rehabil Health Stud. 2020;7(1):e96775. https://doi.org/10.5812/mejrh.96775

» https://doi.org/10.5812/mejrh.96775 -

41. Perme C, Schwing T, deGuzman K, Arnold C, Stawarz-Gugala A, Paranilam J, et al. Relationship of the Perme ICU Mobility Score and Medical Research Council Sum Score With Discharge Destination for Patients in 5 Different Intensive Care Units. J Acute Care Phys Ther. 2020;11(4):171-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/jat.0000000000000132

» https://doi.org/10.1097/jat.0000000000000132 -

42. Luna ECW, Oliveira AS, Perme C, Gastaldi AC. Spanish version of the Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score: Minimal detectable change and responsiveness. Physiotherapy Res Intl. 2021;26(1):e1875. https://doi.org/10.1002/pri.1875

» https://doi.org/10.1002/pri.1875 -

43. Rittel CM, Borg BA, Hanessian AV, Kuhar A, Fain MJ, Bime C. Longitudinal Assessment of Mobility and Self-care Among Critically Ill Older Adults. An Age-Friendly Health Systems Initiative Quality Improvement Study. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2023;42(4):234-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000588

» https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000588 -

44. Beaton D, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Recommendations for the Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the DASH & Quick DASH Outcome Measures [Internet]. Toronto: Institute for Work & Art; 2007 [cited 2024 Apr 26]. Available from: https://dash.iwh.on.ca/sites/dash/files/downloads/cross_cultural_adaptation_2007.pdf

» https://dash.iwh.on.ca/sites/dash/files/downloads/cross_cultural_adaptation_2007.pdf

-

1

USD exchange rate = R$ 5.84, on 02/01/2025

-

How to cite this article

Lenardt MH, Cechinel C, Zomer TB, Rodrigues JAM, Binotto MA, Spoladore R. Evidence of the use of the Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score in hospitalized adults: a scoping review. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem. [cited]. Available from: .https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.7491.4542

Edited by

-

Associate Editor:

Maria Lúcia Zanetti

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

02 May 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

26 Apr 2024 -

Accepted

29 Dec 2024

Evidence of the use of the Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score in hospitalized adults: a scoping review

Evidence of the use of the Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score in hospitalized adults: a scoping review